- 1Sanya Research Institute & Institute of Tropical Bioscience and Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, Haikou, China

- 2Department of Botany, Government College University Lahore, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan

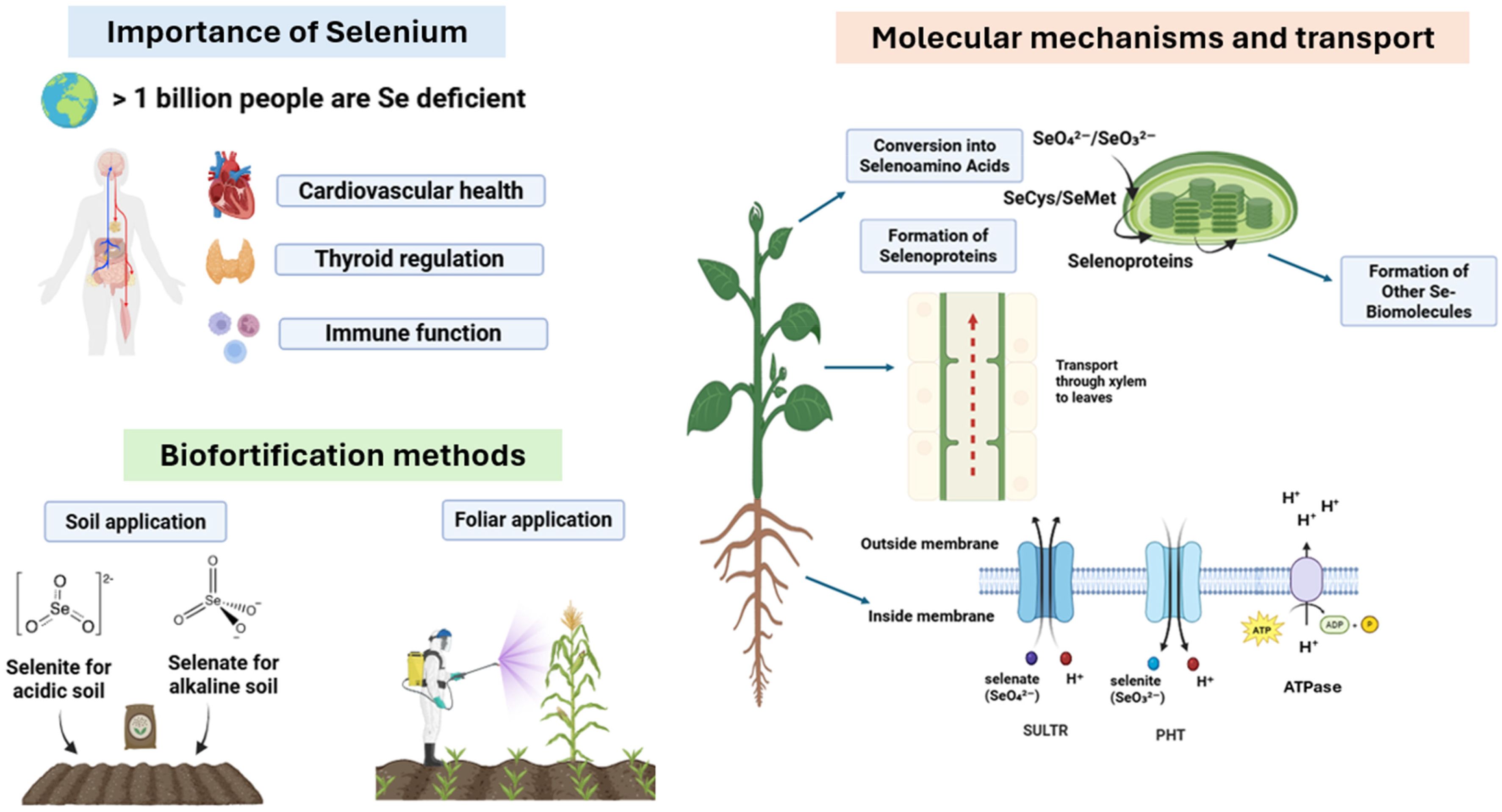

Selenium (Se) is an essential element for humans. Biologically, it is incorporated into selenoproteins, which play crucial roles in thyroid hormone metabolism, immune system regulation, and antioxidant capacity. However, Se deficiency is a global health concern, affecting over 1 billion individuals, and the production of Se-fortified crops is inevitable. As a way forward, the biofortification of horticultural crops could improve Se nutrition. For plants, Se is a beneficial element, and crops exhibit significant variation in their ability to uptake Se which is also influenced by soil pH. Therefore, this review focuses on recent advancements in Se biofortification technologies for horticultural crops, including soil and foliar application methods, and explores the physiological processes and genetic mechanisms underlying Se uptake, transport, and assimilation in these crops. Furthermore, the effectiveness of different Se-salts in the regulation of Se levels in crops has been discussed, with special emphasis on the mechanisms involved.

1 Introduction to selenium nutrition

Selenium (Se) is a member of the chalcogen family and is required for key cellular physiological functions in humans (Banuelos et al., 2023). Trace quantities of Se in the diet are critical for disease prevention because they support the immune system (Lan et al., 2024). In contrast, its deficiency is linked to Keshan disease, a cardiovascular disease primarily affecting children and females, and bone disease, which is a chronic, degenerative osteoarticular disorder (affects bones and joints (Rayman, 2012). Other health conditions include thyroid disorders, autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer, which can lead to death (Ekumah et al., 2021; Duță et al., 2025). It is estimated that approximately 0.5–1 billion individuals exhibit inadequate Se uptake, which is a serious health concern (Jones et al., 2017; Dinh et al., 2019). Alternatively, adequate Se uptake boosts immunity in both animals and humans. In China, agricultural lands are deficient in Se, and approximately 60% of the Chinese population suffers from inadequate dietary Se intake, which is a serious health concern (Liu et al., 2021a).

Selenium is a beneficial element that affects plant growth under certain environmental conditions. Human selenium nutrition is primarily linked to the consumption of plant-based foods, with fruits and vegetables serving as important sources. However, its uptake is dependent on the plant species, soil type, and available forms of Se. Naturally, Se occurs in both organic and inorganic forms, depending on soil pH, redox status, and mineral composition (Qu et al., 2023). In general, selenite (SeO32-) tends to predominate in acidic and anaerobic soils, whereas selenate (SeO42-) is abundant in soils with high pH. In addition, Se can exist in the soil in an organic form, such as selenomethionine (SeMet), which ranges from 15-45% of the soluble Se fraction, depending on the soil type (Yamada et al., 1998; Supriatin et al., 2015). It is pertinent to mention that SeMet only represents a very small fraction of organic Se of the total available Se. Therefore, bioavailable Se in soil is predominantly present in inorganic forms, such as selenate and selenite. Seleniferous soils can exhibit Se concentrations of up to 10 µg g-1 (McNeal and Balistrieri, 2015). For non-seleniferous soils, Se in soil typically ranges between 0.01 and 2 µg g-1, averaging 0.4 µg g-1 (Wang et al., 2022a). It is essential to clarify that Se deficiency is also prevalent in most global soils, but this does not imply that all non-seleniferous soils are deficient. Seleniferous soils (naturally enriched in Se) provide adequate selenium without deficiency risks; however, non-seleniferous soils (the majority) typically exhibit selenium deficiency, although localized variations exist.

As previously mentioned, the uptake of Se by plants is complex and is influenced by several factors. Both phosphorus (P) and sulfur (S) compete with plant root Se uptake owing to their structural similarities and shared uptake pathways. Furthermore, different elements compete with Se for translocation, thereby limiting its uptake (Ribeiro et al., 2016; Gui et al., 2022). In addition, plants have a very limited capacity to absorb Se from the soil, which makes Se nutrition challenging (Nie et al., 2024). The current review focuses on recent developments in the Se biofortification of horticultural crops, including fruits and vegetables. This study presents an in-depth analysis of the key physiological processes involved. This will pave the way for future research on the biofortification of crops cultivated under a wide range of environmental conditions.

2 Research progress on selenium-enriched foods

The Chinese Society of Nutrition recommends a daily selenium intake of 60 µg for adults, whereas the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a daily selenium intake of 60-200 µg for healthy adults, with a tolerable upper intake level of 400 µg (Kipp et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2021). Approximately 15% of the global population exhibits a lower Se intake (WHO, 2004), over 1 billion individuals worldwide suffer from Se deficiency, and 70% of Chinese soils are Se deficient (Stoffaneller and Morse, 2015). In a comprehensive review, Zhao et al. (2024) reported significant regional variations in soil Se levels across different Chinese provinces. The study concluded that Se concentrations in soils were also dependent on soil parent material, with high Se contents in siliceous rocks; however, plant Se uptake was not dependent on total soil Se concentration (Zhao et al., 2024). Therefore, the Se levels in plants are insufficient to meet human requirements (Broadley et al., 2006; Dijck-Brouwer et al., 2022). In general, plants vary in Se uptake capacity and can be grouped as non-accumulators (<100 μg g-1 DW), accumulators (100-1000 μg g-1 DW), and hyper-accumulators (>1000 μg g-1 DW). Approximately 100 dicot species have been identified as Se hyperaccumulators across different families (White, 2016). Moreover, the uptake, translocation, and assimilation of different forms of Se vary among different plant species. The most abundant form of Se in edible seeds and vegetables is SeMet. However, Se non-accumulator species metabolize inorganic selenium into organic forms, primarily SeMet in grains and legumes; therefore, selenate is not the terminal product (Smrkolj et al., 2007; Shao et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2017).

Selenium is beneficial to plants in trace quantities, and Se biofortification of crops has gained particular attention in recent years. Horticultural crops can serve as a source of Se to counter Se malnutrition in humans; however, this is a complex approach that depends on multiple factors. Various researchers have reported the beneficial effects of Se application on plants, and considerable success has been achieved in terms of Se biofortification in crops. In cereals, the Se content can be enhanced by foliar application of seleniferous compounds (Radawiec et al., 2021). For instance, seleno-cyanoacetate application causes the accumulation of selenomethylcysteine (SeMeCys) in brown rice (Yuan et al., 2023). In addition, the combined application of SeMet and P enhanced selenocysteine (SeCys) levels in winter wheat (Hu et al., 2023). It has also been reported that SeCys are more effective and enhance Se translocation in grains and further assimilation into organic compounds (Liu et al., 2023a). Exogenous Se also improves the crop quality characteristics of wheat and maize (Broadley et al., 2010; Zahedi et al., 2019). In fruits, Se foliar spraying improved the Se content in apples and oranges (Wojcik, 2023; Wang et al., 2024). Improvements in the quality characteristics of strawberries and their Se content by exogenous Se have also been reported (Zahedi et al., 2019). In addition, biofortification of vegetables, legumes, forages, and medicinal plants has been performed (reviewed by Huang et al., 2024b). The foliar application of sodium selenate and Se nanoparticles (10 mg L-1) improved the biochemical composition of tomato fruits, including protein-related quality parameters (Shiriaev et al., 2023). Similarly, potato treated with nano-Se fertilizer exhibited upregulation of the enzyme activities of GSH, POD, PPO, SOD, and PAL and increased vitamin C and protein content in tubers (Liu et al., 2025). Similarly, soil and foliar application of exogenous Se improved citrus quality (Wang et al., 2024). Four-time application of Na2SeO4 at 15 g ha−1 spray−1 improved Se content in fruits up to 12 folds (Wójcik, 2024). A summary of different studies related to the biofortification of different horticultural crops is presented (Table 1).

3 Technical means of selenium nutrition enhancement

It is believed that higher plants lack the ability (e.g., the selenocysteine insertion machinery guided by the UGA codon) to incorporate Se into proteins in a specific manner. It is believed that Se can be non-specifically incorporated into proteins by replacing cysteine or methionine residues (Cone et al., 1976). Selenocysteine (SeCys) insertion in proteins is dictated by the UGA codon (a termination signal), which requires SeCys insertion sequence (SECIS) elements (Berry et al., 1991). A selenocysteine insertion sequence and a pair of tRNA-Sec have been identified in the mitochondrial genome of cranberries (Fajardo et al., 2014). Although the exact mechanism remains unclear, it has been identified that an elongation factor, EEFSEC, recognizes the extended variable arm of tRNA[Ser]Sec, which also contains some modifications in its anticodon loop, including i6A (N6- isopentenyladenosine) at position 37 and two forms of 5-methoxycarbonylmethyluridine (mcm5U and mcm5Um) at position 34 (see detailed review by Chavatte et al., 2025). Nonetheless, an efficient way to improve Se nutrition in crops and promote its assimilation into the human diet is to use Se in soil or as a foliar spray for horticultural crops. Also, the Se-enriched fertilizers have been used globally for a long time (Ogunsuyi et al., 2025). In this section, we provide in-depth details regarding the pros and cons of Se-soil and foliar-based applications to draw parallels between them and to highlight which approach is better.

3.1 Insights into Se application in soils and associated considerations

To address Se deficiency in humans, the application of Se-rich fertilizers to soil is recommended. However, the direct addition of Se to soil does not ensure the success of Se-enriched crops because of several factors. Plant root Se uptake is primarily dependent on soil physicochemical properties, such as pH, Eh, and Se form applied.

Se naturally exists as selenide, elemental selenium, thioselenate (Se2O32-), selenite (SeO32-), and selenate (SeO42−), corresponding to the five oxidation states of Se2-, Se0, Se2+, Se4+, and Se6+, respectively (Guo et al., 2023). Additionally, soils may contain various forms of organic Se, such as SeMet, SeCys, and MeSeCys (Thiry et al., 2012). However, only SeO42- and SeO32- are the dominant Se oxyanions in the soil solution absorbed by plant roots (Dinh et al., 2019), whereas other Se species can be adsorbed onto Fe and Mn oxides or even organic matter, making them unavailable to plants (Weng et al., 2011; Lyu et al., 2021; Guo et al., 2023). Nonetheless, it has also been well established that plants cultivated in alkaline soils prefer SeO42- (+6 oxidation state), whereas those in acidic soils tend to take up SeO32- (+4 oxidation state) (Elrashidi et al., 1987). Plants take up other forms of Se, including organoselenium species, SeMet, and SeCys (König et al., 2012). Similarly, in wheat plants cultivated in acidic soils, selenite uptake is preferred over selenate uptake (Kikkert and Berkelaar, 2013).

Therefore, SeO42- becomes more bioavailable in oxic soils, whereas SeO32- dominates anaerobic acidic soils (Mikkelsen et al., 1989; Bassil et al., 2018). Furthermore, under reduced conditions (Eh < -200 mV), SeO32- can be converted to insoluble Se species (Se0 and Se2-), thereby reducing its bioavailability (Nakamaru and Altansuvd, 2014; Bassil et al., 2018). This also tightly binds SeO3- and locks it into the soil profile, causing Se deficiency in crops (Peak and Sparks, 2002; Kumar et al., 2011). In alkaline soils, SeO32- can be oxidized to SeO42- (Dinh et al., 2019). It has been estimated that approximately half of the total Se concentration in soil is locked with clay minerals and organic matter, making it unavailable to plants (Weng et al., 2011; Qin et al., 2012). Soil amendment with either SeO42- or SeO32- causes a very high leaching rate (Zhai et al., 2019). In addition, depending on the soil pH, the available SeO32- can exist as H2SeO3 (at pH 3), HSeO3− (at pH 5), and SeO32− (at pH 7) (Hopper and Parker, 1999; Wang et al., 2019). It is pertinent to mention that phosphate transporters and anion channels contribute to the uptake of HSeO3− and SeO32− in plants, which exist at pH 5 and pH 7, respectively (Zhang et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2024). In contrast, SeO42- uptake occurs via sulfate transporters, and S-starvation contributes to a 10-fold increase in Se uptake (Li et al., 2008). However, the Se-hyperaccumulator Stanleya pinnata did not show any competitive inhibition, even at a 100-fold excess of sulfate (El Mehdawi et al., 2018). In contrast, Se uptake in Brassica juncea was reduced by 40%, and in Stanleya elata, it was reduced by 100% (El Mehdawi et al., 2018). A hydroponic study revealed that a lower supply of S increased Se content and root-to-shoot translocation in Brassica napus by 06 times (Ren et al., 2023). Similarly, findings of field experiments from Rothamsted, UK revealed upregulation of sulfate transporters (SULTR1;1 and SULTR4;1) under reduced S supply, which contributed to 07-fold Se increase in wheat grain (Shinmachi et al., 2010). Considering that the soil application of Se does not seem to be a plausible approach because most of the uptake would be dependent on soil physiochemical attributes, it is challenging. A list of previous studies in which Se was applied directly to the soil and its subsequent contribution to Se biofortification is presented (Table 2).

Table 2. Biofortification of Se in horticultural crops by soil/root zone application - recent reports.

3.2 Foliar application of Se on plants

Foliar application of Se is an effective approach for directly delivering Se to leaves. Unlike Se immobilization in soils, foliar Se application promotes its uptake and transport in leaves. This approach utilizes a low concentration of Se compounds and is safe, convenient, and cost-effective, ensuring optimized and precise Se delivery to plants (de Lima et al., 2023). For instance, the foliar application of Na2SeO3 increased the Se fraction in strawberries, which was further reduced to Se2- and assimilated into organic forms (Lin et al., 2024). Several other studies have reported the success of foliar Se sprays in enhancing the Se content of plants. For instance, foliar spray of Se at a concentration of 200 mg L-1 at different fruit development stages substantially enhanced the Se fraction in leaves and citrus fruits compared with soil application (Wang et al., 2024). Rice Se levels were enhanced–5–6 times with a foliar spray of selenite (Lidon et al., 2019). Similarly, foliar application of Na2SeO3 enhanced Se enrichment in persimmons (Yan et al., 2021), jujubes (Wang et al., 2020a), and strawberries (Huang et al., 2023).

Two key enzymes, O-acetyl serine (OAS) and cysteine synthase, convert Se2- into SeCys, which can be further methylated into methyl-SeCys (by selenocysteine methyltransferase) or SeMet by selenocysteine lyase (Adebayo et al., 2020). Similarly, organic Se is the dominant assimilated form of Se in fruit (Sarwar et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2024). It has also been reported that Se-amino acids can replace S-containing amino acids in proteins (Zagrodzki et al., 2023). However, this depends on several factors, including Se concentration, Se compound application, mode of application, and plant developmental stages (Schiavon et al., 2017). Recently, we reported that foliar spray of Na2SeO3 at concentrations up to 200 mg L-1 improved fruit quality in Citrus reticulata and enhanced Se content in fruit by 3.6 folds (Wang et al., 2024). At the field scale, the repeated application (four applications per year) of Na2SeO4 in combination with CaCl2 enhanced cherry fruit Se content up to 12 folds (Wójcik, 2024). So far, Se biofortification has been successfully achieved in fruits, vegetables, and cereal crops through foliar application, as summarized in Table 3.

4 Se-uptake, transport, and assimilation pathways and genes involved therein

4.1 Selenium uptake

Plant roots exhibit different uptake pathways for selenate (SeO42-) and selenite (SeO32-), which vary among Se non-accumulator and hyperaccumulator species (Lima et al., 2018). It was initially believed that selenite enters plant roots by passive diffusion, but later studies confirmed the active root uptake of Se species via low- and high-affinity transporters (Shrift and Ulrich, 1969; Zhang et al., 2003; Li et al., 2008). Moreover, the root uptake capacity of different Se species varies depending on pH, with HSeO3− being the dominant form taken up by tomato and maize plants (Zhao et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2019). Interestingly, the uptake of both selenate and selenite follows different uptake pathways and transporters in the root cell plasma membrane, and both S and P are two macronutrients affecting Se uptake by roots, which have been discussed in detail.

4.1.1 Selenate [Se(VI)] uptake by sulphate transporters

As mentioned earlier, selenate [SeO42-; Se(VI)] dominates alkaline soils because of its structural and chemical similarities to S and is primarily taken up by roots via sulfate transporters (Anderson, 1993; Sors et al., 2005; White, 2016). In general, sulfate transporters belong to four gene families: SULTR1, SULTR2, SULTR3, and SULTR4, which primarily regulate S uptake, transport, and regulation within plants (El Mehdawi et al., 2018).

Among these, SULTR1 transporters are high-affinity S-transporters (H+/sulfate symporters) localized inside root cells (Sors et al., 2005; Shinmachi et al., 2010). In Arabidopsis, AtSULTR1;2 is highly expressed in the root tips, lateral roots, and root cortex (Shibagaki et al., 2002). Both SULTR1;1 and SULTR1;2 mediate root S uptake in plants. Interestingly, AtSULTR1;2 knockout mutants exhibit reduced S and Se uptake in roots, suggesting their involvement in Se uptake (Ohno et al., 2012). Similarly, elevated expression of SULTR1 genes has also been found in Se-hyperaccumulator plant species (Cabannes et al., 2011; El Mehdawi et al., 2018). Elevated expression of SULTR1;1 is consistent with increased selenate uptake in wheat and lettuce (Ramos et al., 2011; Boldrin et al., 2016). Similarly, both AtSULTR1;1 and AtSULTR1;2 catalyze root Se uptake in Arabidopsis under high and normal Se conditions (Rouached et al., 2008). These reports suggest a substantial involvement of SULTR1 transporters in root selenate uptake from the soil solution. In contrast, the SULTR2 gene family is involved in S and Se xylem loading and transport to aboveground plant parts. The Se hyperaccumulator plant species often exhibit high SULTR2;1 expression (Cabannes et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2018). Moreover, increased SULTR2;1 expression has been reported in broccoli, rice, and tea plants in response to exogenous selenate application, confirming its role in Se transport (Zhang et al., 2020a; Ren et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022). Additionally, SULTR3 transporters are involved in chloroplast S uptake, whereas SULTR4 transporters are involved in S efflux from the vacuole.

As no dedicated Se transporters have been identified in plants, selenate uptake in plants primarily follows the S-transport pathway. This suggests that root Se uptake occurs via SULTR1, followed by xylem loading via SULTR2, and then transport to the chloroplast via SULTR3 for possible reduction to selenite and incorporation into organic compounds. Consistent with this assumption, selenate treatment increases the expression of SULTR3;1, SULTR3;5, and SULTR4;1 in cabbage, wheat, and broccoli, respectively (Boldrin et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022). Se/S homeostasis via vacuolar sequestration may involve the SULTR4. The ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) transporters and MOTI (which functions in molybdate/sulfate transport across the plasma membrane) may also be involved in root uptake of Se; however, this has not yet been reported.

4.1.2 Selenite [Se(IV)] uptake by phosphate transporters

Initially, it was believed that selenite (SeO32-) uptake by roots was a passive process, but later studies confirmed its active uptake at rates comparable to or even higher (Hopper and Parker, 1999; Li et al., 2008). Phosphate application has also been found to suppress SeO32- uptake (Hopper and Parker, 1999). Similarly, increasing P supply inhibits SeO32- root uptake in rice, whereas P starvation promotes its uptake (Li et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Studies have supported the notion that SeO32- uptake is primarily mediated by phosphate transporters (PHTs) (Li et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2014; Song et al., 2017). In general, phosphate transporters can be classified into four gene families: PHT1, PHT2, PHT3, and PHT4 based on sequence, conserved domains, and functions (Okumura et al., 1998; Rausch and Bucher, 2002; Zhang et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2017). The PHT1 transporters are localized in the plasma membrane, whereas PHT2 and PHT3 are localized in the plastid inner envelope and mitochondrial membrane, respectively (Knappe et al., 2003; Młodzińska and Zboińska, 2016). Furthermore, PHT4 is located within plastids and the secretory system (Guo et al., 2008).

In tea plants, Se-mediated regulation of CsPHT1 has been reported, suggesting its role in Se uptake (Cao et al., 2021). Similarly, OsPT2 and OsPT8 contribute to the uptake of selenite in rice. The PHT1 subfamily encodes an H+ symporter involved in Pi uptake in Arabidopsis thaliana (Młodzińska and Zboińska, 2016). Additionally, it has been proposed that a conformational change in the phosphate-H+ symporter contributes to SeO32 − anion uptake (Song et al., 2017). In contrast, AtPHT2;1 is involved in Pi translocation and allocation to leaves (Daram et al., 1999; Versaw and Harrison, 2002). However, OsPT2 is involved in selenite uptake (Zhang et al., 2014). Interestingly, CsPHT gene expression was upregulated in response to low, medium, and high Se treatments and positively correlated with Se uptake (Cao et al., 2021). It is pertinent to mention that the PHT3 subfamily in Arabidopsis is expressed in the stems, leaves, and flowers (Poirier and Bucher, 2002). As the PHT3 gene encodes mitochondrial Pi transporters, it suggests a major role in Se uptake and reduction. Taken together, these results suggest that PHT2 and PHT3 are involved in Se translocation to leaves and its subsequent allocation to plastids, where it is further reduced to Se-organic compounds. In addition, the expression of AtPHT4 genes has been reported in the roots and leaves of Arabidopsis and AtPHT4;6 regulates Pi transport from the Golgi to the cytosol (Guo et al., 2008). Additionally, PHT4;2 contributes to Pi transport in isolated root plastids and was also identified as a plastidic Pi translocator, pPT, whose expression is mainly confined to roots during vegetative development (Irigoyen et al., 2011). Recently, upregulation of CsPHT4 gene expression in response to Se application has been linked to endomembrane function (Cao et al., 2021). In contrast, we propose that the function of PHT4 is in tandem with that of PHT2, and therefore, it contributes to the synthesis of organic Se compounds inside root plastids. Therefore, root plastids import ATP from the cytosol (Irigoyen et al., 2011), which likely aids in SeO32- reduction.

Little is known about how other phosphate transporters, including PHT5, SPX, and PHO1 regulate selenite uptake and metabolism in plants. It is pertinent to mention here that PHT5 is a vacuolar phosphate transporter1 localized in the tonoplast involved in Pi homeostasis, whereas PHO1 is involved in xylem Pi loading and is present in root vasculature, and SPX is reported to regulate Pi signaling (Wang et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016). Additionally, PHO1 is localized in the plasma membrane and Golgi apparatus, and plays a role in root-shoot xylem transport (Arpat et al., 2012; Lopez-Arredondo et al., 2014). Therefore, if we draw parallels by following the path of Pi, it could be speculated that PHO1 might regulate selenite xylem loading and its subsequent translocation to the shoot, whereas PHT5 may be involved in cellular Se homeostasis. Depending on the soil pH, selenite exists as either H2SeO3 (at pH 3), HSeO3− (at pH 5), or SeO32− (at pH 7) and these Se-species are differentially taken up different phosphate transporters. As mentioned earlier, phosphate transporters and anion channels contribute to the uptake of HSeO3− and SeO32− in plants which exist at pH 5 and pH 7 respectively (Zhang et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2024). However, the H2SeO3 uptake is mediated by the silicon transporters (Zhao et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2019). Therefore, further studies are required to validate these assumptions to improve our understanding of the comparative regulation of P and Se within plant cells.

4.1.3 Involvement of nitrate, silicon, and aluminum transporters

The role of these transporters in Se uptake is not properly understood, as only a few studies have reported the interactions of NO32-, Si, and Al transporters in Se uptake. Wang et al. (2022b) reported the transport of SeMet by NRT1.1B from leaves to seeds. Aquaporin and Si influx transporters, OsNIP2;1, have been reported to enhance the uptake of SeO32- in rice and yeast (Zhao et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2023). However, Zhao et al. (2010) showed that increasing the Si concentration in the solution affects Se uptake in rice roots. Moreover, the selenite uptake greatly enhanced at acidic pH up till 5.5 and the authors concluded that the Si- transporter (OsNIP2;1) is permeable to SeO32- (Zhao et al., 2010). In another study, Wang et al. (2019) also reported that root SeO32- in tomatoes remained unaffected by Si addition at a pH above 5. However, their study provided evidence that H2SeO3 can be taken up by the roots by Si transporters in tomatoes. Other candidates include members of the Aluminum-activated Malate Transporter (ALMT) family. AtALMT12 was found to be involved in root SeO42- xylem loading, potentially involving the SULTR2 and SULTR3 transporters (Gigolashvili and Kopriva, 2014). In short, these reports suggest a very limited or indirect role for Si influx transporters in root Se uptake.

4.2 Selenium accumulation and transport

Inside the plant cells of roots and shoots, the majority of Se (60-75%) is adsorbed onto the cell wall (Ding et al., 2015). Some Se remains in the cytosol in its soluble form, while others are transported to organelles (Wang et al., 2020c). In addition, the vacuoles of the leaf mesophyll cells and vasculature also serve as a major sequestration point for Se (Ximénez-Embún et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2015) and AtSULTR4;1 and AtSULTR4;2 possibly mediate Se efflux from vacuoles (Kataoka et al., 2004; Gigolashvili and Kopriva, 2014). Selenium hyperaccumulators typically exhibit elevated expression of genes encoding both these transporters as well as in response to Se supplementation, thereby suggesting a significant role in Se homeostasis (Both et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022d; Yang et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2025).

The translocation mechanisms for both selenate and selenite are also substantially different depending on the Se compound applied. Selenate is the dominant Se species in the vasculature (Li et al., 2008). Earlier Zayed et al. (1998) reported that selenate supplementation caused a Se shoot/root ratio ranging between 1.4-17.2, whereas selenite caused a ratio less than 0.5. Similarly, rice plants treated with selenite exhibited a translocation factor of 0.21, indicating limited transport to the shoots (Wang et al., 2020c). This clearly indicates that selenate is more actively translocated to the shoot than selenite. In contrast, selenite transport was very low, further indicating its assimilation into Se organic compounds in roots (Huang et al., 2017). Therefore, selenate follows a symplast pathway from root to shoot, and SULTR transporters are primarily involved in leaf selenate uptake (White et al., 2004; Li et al., 2008; Takahashi et al., 2011; Gigolashvili and Kopriva, 2014). However, selenoamino acids synthesized from selenite reduction in roots are directly translocated to shoots via xylem tissue (Li et al., 2008; Guignardi and Schiavon, 2017). Moreover, the phloem redistribution of both selenate and organo-Se compounds has been reported (Carey et al., 2012), which suggests an active source-to-sink relationship and Se homeostasis. Nonetheless, AtSULTR1;3, AtSULTR2;2, and amino acid transporters facilitate Se transport through the phloem (Takahashi et al., 2000; Yoshimoto et al., 2003; Tegeder, 2014; Boldrin et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2024).

Apart from this, plant roots can uptake various organic Se forms, particularly selenoamino acids (SeMet, SeCys and MeSeCys) and selenoproteins (released from decaying organic matter). In fact, the uptake of organic forms of Se in both wheat and canola was way higher than inorganic forms. A 300-minute exposure of durum wheat roots to 5 µM Se treatments resulted in selenate (5.9 µg Se g-1 DW), selenite (15 µg Se g-1 DW), SeCys (60 µg Se g-1 DW) and SeMet (350 µg Se g-1 DW) respectively (Kikkert and Berkelaar, 2013). Likewise in canola, the root uptake of selenate (45 µg Se g-1 DW), selenite (68 µg Se g-1 DW), SeCys (109 µg Se g-1 DW) and the SeMet was around 1800 µg Se g-1 DW (Kikkert and Berkelaar, 2013). In algae, the SeMet uptake inhibited methionine suggesting the involvement of amino acid transporters in Se-amino acids (Sandholm et al., 1973). Therefore, selenoamino acids may be taken up by H+-coupled amino acid transporters via both symplastic and apoplastic routes. Furthermore, the Amino Acid Permeases (AAPs) and Lysine-Histidine like Transporters (LHTs) might be involved in Se-amino acid uptake and its transport through plant vasculature (Guo et al., 2021).

4.3 Selenium assimilation

Generally, it is believed that Se assimilation primarily occurs in roots, and upon its uptake, Se can be incorporated into Se-amino acids (SeCys), SeMet, and MeSeCys) through the S-metabolic pathway (Whanger, 2002; Sors et al., 2005; Rayman et al., 2008). Multiple studies have confirmed the presence of seleno-amino acids, such as SeCys, MeSeCys, and SeMet, in roots when compared to shoots (Huang et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2018).

In contrast, Li et al. (2008) showed that selenate is actively transported to wheat shoots (without being incorporated into amino acids). In contrast, selenite was rapidly incorporated into Se-amino acids by the roots within 3–4 minutes of supplementation. Similarly, selenite-treated rice roots exhibited SeMet as the dominant Se species (Yu et al., 2019). This clearly shows the preference of the roots for the reduced Se form (selenite) over the oxidized form (selenate), which can be explained by several factors. It has also been reported that the SeO42- to SeO32- reduction is the rate-limiting step in plant Se metabolism in non-hyperaccumulators (Sors et al., 2005). First, plant tolerance to Se compounds varies, and organo-Se compounds are believed to be safer than inorganic forms (Thiry et al., 2012). Therefore, it is safer to convert available Se to Se-amino acids within the roots. In addition, the reduction of inorganic Se into organo-Se requires reducing equivalents, and this process exclusively occurs within plastids. The plastids in the roots have a very limited supply of reducing power; therefore, they prefer selenite over selenate. Selenoamino acids are primarily synthesized inside the leaf chloroplasts (Terry et al., 2000; White, 2018b; Trippe III and Pilon-Smits, 2021). In the leaf, selenate is transported to plastids via the homologs of AtSULTR3;1 located at chloroplast membranes, where it is reduced and incorporated into Se-amino acids through S-metabolism. Additionally, the seleno-amino acids taken up by the roots be directly incorporated into the proteins. The assimilation of SeMet might undergo activation by methionyl-tRNA synthetase which results in the formation of selenomethionyl-tRNA which then incorporated into the newly synthesized proteins by ribosomes. Likewise, the SeCys can be incorporated into the proteins substituting cysteine (which can also lead to disruption of disulfide bonds).

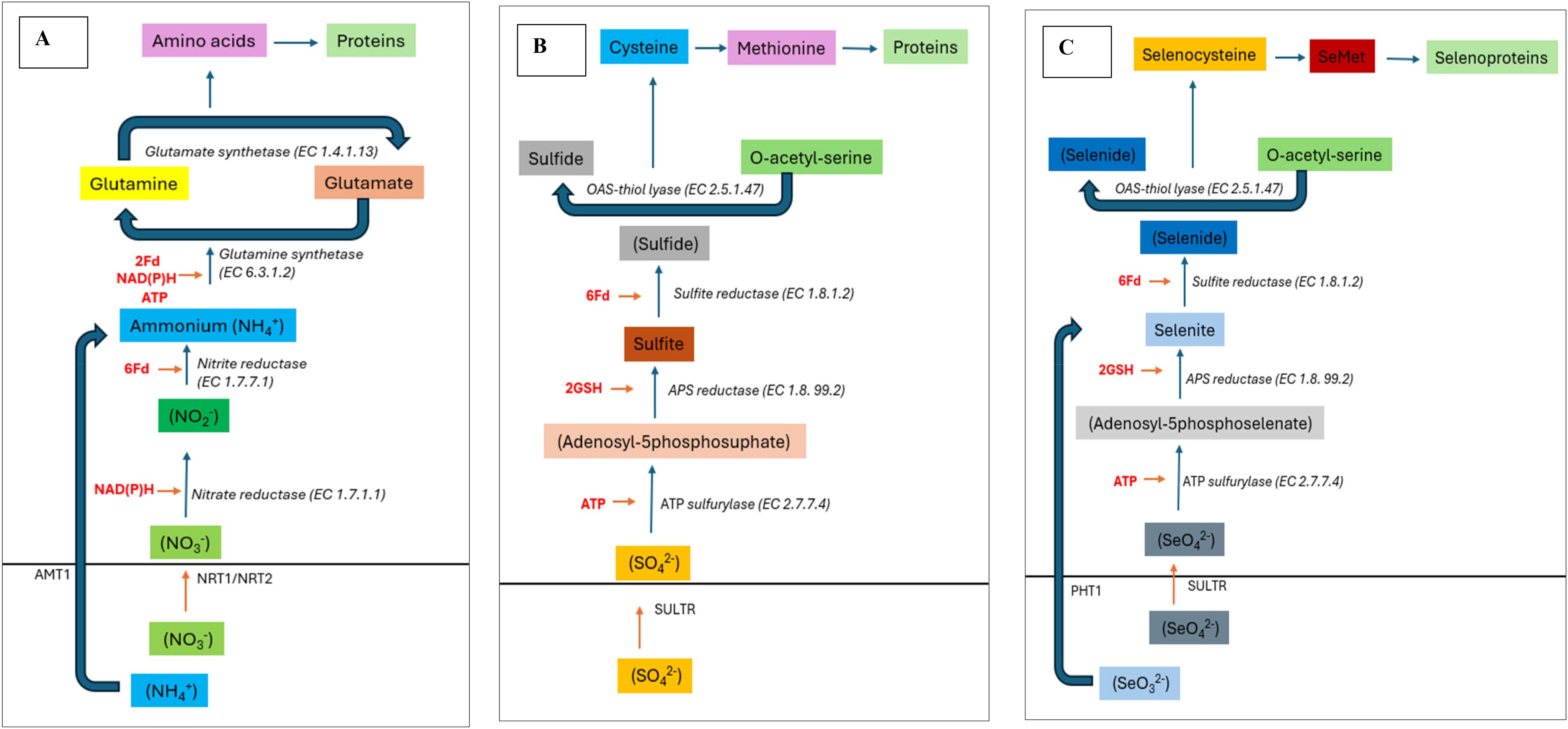

Selenium hyperaccumulators typically exhibit elevated expression of genes involved in S-metabolism, which becomes very high in Se hyperaccumulators (Van Hoewyk et al., 2005, 2008; Schiavon et al., 2015). First, adenosine triphosphate sulfurylase (APS) converts selenate into adenosine 5′- phosphoselenate, also called APSe (Bohrer et al., 2015). Later, selenoglutathione and selenolipids were formed from APSe via analogous S pathways (Duncan et al., 2017). Selenite can also be synthesized by adenosine 5′- phosphosulfate reductase (APR), which is a rate-limiting step that uses glutathione as an electron donor (Pilon-Smits et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2018). Furthermore, selenite reduction can be enzymatically (by sulfite reductase) or non-enzymatically (glutathione oxidoreductase), facilitating its incorporation into Se-amino acids (González-Morales et al., 2017; Van Hoewyk and Çakir, 2017; Zhong et al., 2024). Once synthesized, selenoamino acids are incorporated into selenoproteins (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram showing the importance and methods for enhancing Se biofortification in crops alongside molecular mechanisms involved therein.

4.4 Seleno-biomolecules

Both Se and S have different ionization energies and atomic/ionic radii, which influence protein structure and folding properties. The radius of Se2+ is 0.5A°, whereas that of S2+ is 0.37 A° (Terry et al., 2000). In contrast, S and Se share a similar primary metabolism, and accumulation of Se in tissues can replace S-rich metabolites, thereby mediating a wide range of plant physiological responses (reviewed by White, 2018a). Se accumulation in albumin, globulins, and prolamin has been reported previously (Liu et al., 2011; Nwachukwu and Aluko, 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). In addition, selenoproteins exhibit better redox activity and utilize SeCys as a catalytic residue, which provides greater nucleophilicity, reactivity, and resistance to permanent oxidation (Reich and Hondal, 2016; Schomburg and Arnér, 2017). In addition, some studies have reported that Se bioaccumulation promotes SOD synthesis, thereby assisting antioxidant capacity (Georgiadou et al., 2018). Alternatively, the exogenous application of Se as a foliar spray enhances gene expression related to antioxidant defense pathways (Lanza and Reis, 2021).

Apart from selenopeptides and antioxidants, various metabolites are derived from SeMet and SeCys (Reviewed by White, 2018). These include selenoglutathione (Crawford et al., 2000; Pivato et al., 2014), S-allyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide (González-Morales et al., 2017), and selenoglucosinolates (Matich et al., 2012; Ouerdane et al., 2013; Matich et al., 2015). Moreover, foliar application of Se has been reported to enhance quality traits in citrus (Wang et al., 2024), potatoes (Ibrahim and Ibrahim, 2016), sapotas (Lalithya et al., 2014), and pomegranates (Zahedi et al., 2019). Studies have also revealed Se-mediated enhancement in the enzymatic activity of fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase, resulting in the enhancement of total soluble sugars in citrus plants (Owusu-Sekyere et al., 2013). Interestingly, selenosugars and selenopolysaccharides have been reported in cereal crops (Aureli et al., 2012; Qi et al., 2024). In addition, exogenous application of Se can also influence ascorbic acid content in citrus fruits (Ibrahim and Al-Wasfy, 2014; Zhan et al., 2021; Wen et al., 2021). Finally, selenoflavonoids have been isolated from various plants. These include the isolation of Se-containing 5,7-dihydroxychromone (Se-DHC) and flavones from Se-enriched green tea (Fan et al., 2022). Se assimilation into biomolecules in plants follows a very diverse route and is actively involved in plant growth, resilience, and survival. Lastly, several studies have reported that exogenous Se led to an increase in the fruit quality characteristics and protein contents. Some of the studies have been summarized in Table 4.

5 Selenium toxicity in plants

Since Se is not essential for most plants and can be toxic at high levels and inhibit plant growth, development and physiological processes, leading to cause symptoms such as chlorosis, necrosis, reduced protein synthesis and stunted growth (Schiavon et al., 2017). Exposure to high Se concentration also caused reduced biomass, lower seed germination rates and decreased pollen production in Brassica juncea (Kushwaha et al., 2022). The Se toxicity is also known as selenosis and primarily arises forming seleno-proteins and the induction of oxidative stress (Hasanuzzaman et al., 2020). Toxic concentration of Se in plant tissues is typically above 5 mg kg-1, however the Se tolerance among different crop plants varies widely. For example, rice and wheat showed toxicity symptoms at 2 and 4.9 mg kg-1 DW Se concentration respectively; whereas Dutch clover tolerated 330 mg kg-1 DW Se without toxic symptoms (Kolbert et al., 2019). Not only this, the severity of Se toxicity also varies depending on the plant species, its age and the level of Se exposure. Younger plants are generally more susceptible to Se toxicity compared to mature plants and selenite (SeO32-) is known to be more harmful than selenate (SeO42-) (Hasanuzzaman et al., 2020). Basically, Se toxicity in plants can be due to selenoproteins-induced toxicity or Se-induced oxidative stress (Ali et al., 2021). Misfolded selenoproteins are produced when SeCys or SeMet are mistakenly incorporated into protein chains in place of cysteine (Cys) or methionine (Met) which affects tertiary structure of proteins. Not only this, the protein stability, enzyme activity, redox potential and its enzyme kinetics are affected leading to toxicity (Reviewed by Gupta and Gupta, 2017). Furthermore, the replacement of Cys with SeCys at the metal binding site increase bond due to larger atomic radii of Se potentially affecting its interaction with the co-factors (Van Hoewyk, 2013). Moreover, Se can act as a pro-oxidant, thereby stimulating over-production of ROS leading to Se-induced phytotoxicity. For instance, the reaction between selenite (SeO32-) and glutathione (GSH) generates superoxide radicals (O2-), resulting in the subsequent accumulation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). As a result, excessive Se depletes GSH levels and reduces its activity, thereby promoting further ROS generation (Hasanuzzaman et al., 2020). Lastly, Se accumulation can also interfere nutrient uptake. It has been reported that excessive Se negatively affects N-metabolism through inhibition of nitrate reductase activity by affecting synthesis of molybdopterin, which serve as cofactor for nitrate reductase and essentially required for nitrogen assimilation. This in turn disturbs N-metabolism and synthesis of amino acids, proteins, nucleotides and vital secondary metabolites affecting a wide range of developmental processes in plants (Gouveia et al., 2020).

6 Conclusions and future perspectives

The review reports recent advancements in Se biofortification technologies in horticultural crops and currently both foliar and soil-based methods are in practice. Selenate is the preferential Se source taken up by the crops cultivated in alkaline soils and roots uptake it through the SULTR transporters. By contrast, crops grown on the acidic soils get benefit from selenite, as a Se source which enters the roots through PHT transporters (competes with P). Future research should focus on how we can improve the Se uptake in horticultural plants without interfering with S and/or P metabolism (Figure 2). Additionally, various crops exhibit differential Se uptake capacity/assimilation into the organic molecules which require further investigation. Lastly, it is also not clearly established that how plant roots respond to inorganic Se (Se-salts), organic-Se and nano-selenium which will improve our understanding and pave the way for crop specific Se-biofortification targets.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram showing ubiquitous nature of pathways involved in the assimilation of N, S, Se required for amino acid synthesis. (A) Nitrogen assimilation in roots follows sequential reduction into nitrite and ammonium which is then incorporated into amino acids. (B) Sulphur assimilation also follows same sequential reduction into sulfite and sulfide before synthesis of S-containing amino acids primarily cysteine and methionine. Lastly, (C) Selenium assimilation follows the sequential reduction into selenite, selenide and finally used to synthesize selenocysteine and selenomethionine which in-turn is incorporated into selenoproteins.

Author contributions

LW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZD: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. YH: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The research was funded by International Cooperation Project (Y20240115), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS31-24), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFD1401105).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdu, A. O., Joy, E. J., De Groote, H., Broadley, M. R., and Gashu, D. (2023). Burden of selenium deficiency and cost-effectiveness of selenium agronomic biofortification of staple cereals in Ethiopia. British Journal of Nutrition, 132(8), 1110–1122. doi: 10.1017/S0007114524001235

Adebayo, A. H., Yakubu, O. F., and Bakare-Akpata, O. (2020). Uptake, metabolism and toxicity of selenium in tropical plants. In Importance of selenium in the environment and human health. IntechOpen. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.90295

Ahmad, A., Javad, S., Iqbal, S., Shahzadi, K., Gatasheh, M. K., and Javed, T. (2024). Alleviation potential of green-synthesized selenium nanoparticles for cadmium stress in Solanum lycopersicum L: modulation of secondary metabolites and physiochemical attributes. Plant Cell Rep. 43, 113. doi: 10.1007/s00299-024-03197-9

Amerian, M., Palangi, A., Gohari, G., and Ntatsi, G. (2024). Enhancing salinity tolerance in cucumber through Selenium biofortification and grafting. BMC Plant Biol. 24, 24. doi: 10.1186/s12870-023-04711-z

Anderson, J. (1993). “Selenium interactions in sulfur metabolism,” in Sulfur Nutrition and Assimilation in Higher Plants: Regulatory Agricultural and Environmental Aspects, vol. 49–60 . Ed. De Kok, I. S. (SPB Academic, Amsterdam).

Arpat, A. B., Magliano, P., Wege, S., Rouached, H., Stefanovic, A., and Poirier, Y. (2012). Functional expression of PHO1 to the Golgi and trans-Golgi network and its role in export of inorganic phosphate. Plant J. 71, 479–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05004.x

Aureli, F., Ouerdane, L., Bierla, K., Szpunar, J., Prakash, N. T., and Cubadda, F. (2012). Identification of selenosugars and other low-molecular weight selenium metabolites in high-selenium cereal crops. Metallomics 4, 968–978. doi: 10.1039/c2mt20085f

Banuelos, G. S., Lin, Z. Q., and Caton, J. (2023). Selenium in soil-plant-animal systems and its essential role for human health. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1237646. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1237646

Bassil, J., Naveau, A., Bueno, M., Razack, M., and Kazpard, V. (2018). Leaching behavior of selenium from the karst infillings of the hydrogeological experimental site of Poitiers. Chem. Geol 483, 141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2018.02.032

Berry, M. J., Banu, L., Chen, Y. Y., Mandel, S. J., Kieffer, J. D., Harney, J. W., et al. (1991). Recognition of UGA as a selenocysteine codon in type I deiodinase requires sequences in the 3′untranslated region. Nature 353, 273–276. doi: 10.1038/353273a0

Bohrer, A. S., Yoshimoto, N., Sekiguchi, A., Rykulski, N., Saito, K., and Takahashi, H. (2015). Alternative translational initiation of ATP sulfurylase underlying dual localization of sulfate assimilation pathways in plastids and cytosol in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 750. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00750

Boldrin, P. F., De Figueiredo, M. A., Yang, Y., Luo, H., Giri, S., Hart, J. J., et al. (2016). Selenium promotes sulfur accumulation and plant growth in wheat (Triticum aestivum). Physiol. Plantarum 158, 80–91. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12465

Both, P. B., Both, V., and Earl, C. (2020). Mechanisms of selenium hyperaccumulation in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 147, 137–146.

Botha, L., Namaumbo, S., Kapito, N. J., Ndovi, P., Tsukuluza, D. C., Jagot, F., et al. (2024). Selenium health impacts and Sub-Saharan regional nutritional challenges. Results Chem. 12, 101920. doi: 10.1016/j.rechem.2024.101920

Broadley, M. R., Alcock, J., Alford, J., Cartwright, P., Foot, I., Fairweather-Tait, S. J., et al. (2010). Selenium biofortification of high-yielding winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by liquid or granular Se fertilisation. Plant Soil 332, 5–18. doi: 10.1007/s11104-009-0234-4

Broadley, M. R., White, P. J., Bryson, R. J., Meacham, M. C., Bowen, H. C., Johnson, S. E., et al. (2006). Biofortification of UK food crops with selenium. P. Nutr. Soc. 65, 169–181. doi: 10.1079/PNS2006490

Buttarelli, M. S., Céccoli, G., Trod, B. S., Stoffel, M. M., Simonutti, M., Bouzo, C. A., et al. (2025). Enhancing nutritional and functional properties of broccoli leaves through selenium biofortification: Potential for sustainable agriculture and bioactive compound valorization. Agronomy 15, 389. doi: 10.3390/agronomy15020389

Cabannes, E., Buchner, P., Broadley, M. R., and Hawkesford, M. J. (2011). A comparison of sulfateand selenium accumulation in relation to the expression of sulfate transporter genes in Astragalus species. Plant Physiol. 157, 2227–2239. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.183897

Cao, D., Liu, Y., Ma, L., Liu, Z., Li, J., Wen, B., et al. (2021). Genome-wide identification and characterization of phosphate transporter gene family members in tea plants (Camellia sinensis LO kuntze) under different selenite levels. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 166, 668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.06.038

Carey, A. M., Scheckel, K. G., Lombi, E., Newville, M., Choi, Y., Norton, G. J., et al. (2012). Grain accumulation of selenium species in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 5557–5564. doi: 10.1021/es203871j

Chavatte, L., Lange, L., Schweizer, U., and Ohlmann, T. (2025). Understanding the role of tRNA modifications in UGA recoding as selenocysteine in eukaryotes. J. Mol. Biol., 169017. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2025.169017

Chen, Q., Yu, L., Zhang, W., Cheng, S., Cong, X., and Xu, F. (2025). Molecular and physiological response of chives (Allium schoenoprasum) under different concentrations of selenium application by transcriptomic, metabolomic, and physiological approaches. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 221, 109633. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.109633

Cheng, H., Shi, X., and Li, L. (2024). The effect of exogenous selenium supplementation on the nutritional value and shelf life of lettuce. Agronomy 14, 1380. doi: 10.3390/agronomy14071380

Chernikova, O., Mazhayskiy, Y., and Ampleeva, L. (2019). Selenium in nanosized form as an alternative to microfertilizers. Agron. Res. 17, 974–981. doi: 10.15159/AR.19.010

Chilala, P., Skalickova, S., and Horky, P. (2024). Selenium status of southern Africa. Nutrients 16, 975. doi: 10.3390/nu16070975

Cone, J. E., Del Rio, R. M., Davis, J. N., and Stadtman, T. C. (1976). Chemical characterization of the selenoprotein component of clostridial glycine reductase: identification of selenocysteine as the organoselenium moiety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 73(8), 2659–2663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.8.2659

Crawford, N. M., Kahn, M. L., Leustek, T., and Long, S. R. (2000). “Nitrogen and sulphur,” in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants. Eds. Buchanan, B., Gruissem, W., and Jones, R. (American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville), 786–849.

Daram, P., Brunner, S., Rausch, C., Steiner, C., Amrhein, N., and Bucher, M. (1999). Pht2;1 encodes a low-affinity phosphate transporter from Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 11, 2153–2166. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.11.2153

de Lima, A. B., De Andrade Vilalta, T., and De Lima Lessa, J. H. (2023). Selenium bioaccessibility in rice grains biofortified via soil or foliar application of inorganic Se. J. Food Compos. Anal. 124, 105652. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2023.105652

Dey, S. and Raychaudhuri, S. S. (2024). Methyl jasmonate improves selenium tolerance via regulating ROS signalling, hormonal crosstalk and phenylpropanoid pathway in Plantago ovata. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 209, 108533. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.108533

Dijck-Brouwer, D. J., Muskiet, F. A., Verheesen, R. H., and Schaafsma, G. (2022). Thyroidal and extrathyroidal requirements for iodine and selenium: a combined evolutionary and (Patho) Physiological approach. Nutrients 14, 3886. doi: 10.3390/nu14193886

Ding, Y. Z., Wang, R. G., Guo, J. K., Wu, F. C., Xu, Y. M., and Feng, R. W. (2015). The effect of selenium on the subcellular distribution of antimony to regulate the toxicity of antimony in paddy rice. Environ. Sci. pollut. Res. 22, 5111–5123. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3865-9

Dinh, Q. T., Wang, M., Tran, T. A. T., Zhou, F., Wang, D., Zhai, H., et al. (2019). Bioavailability of selenium in soil-plant system and a regulatory approach. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 443–517. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2018.1550987

Duță, C., Muscurel, C., Dogaru, C. B., and Stoian, I. (2025). Selenoproteins: Zoom-In to their Metal-Binding properties in neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 1305. doi: 10.3390/ijms26031305

Duncan, E. G., Maher, W. A., Jagtap, R., Krikowa, F., Roper, M. M., and O'Sullivan, C. A. (2017). Selenium speciation in wheat grain varies in the presence of nitrogen and sulphur fertilisers. Environ. Geochem. Health 39, 955–966. doi: 10.1007/s10653-016-9857-6

Ekumah, J. N., Ma, Y., Akpabli-Tsigbe, N. D. K., Kwaw, E., Ma, S., Hu, J., et al. (2021). Global soil distribution, dietary access routes, bioconversion mechanisms and the human health significance of selenium: a review. Food Biosci. 41, 100960. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2021.100960

El-Batal, A. I., Ismail, M. A., Amin, M. A., El-Sayyad, G. S., and Osman, M. S. (2023). Selenium nanoparticles induce growth and physiological tolerance of wastewater‑stressed carrot plants. Biologia, 78, 2339–2355. doi: 10.1007/s11756-023-01401-x

El Mehdawi, A. F., Jiang, Y., Guignardi, Z. S., Esmat, A., Pilon, M., Pilon-Smits, E. A., et al. (2018). Influence of sulfate supply on selenium uptake dynamics and expression of sulfate/selenate transporters in selenium hyperaccumulator and nonhyperaccumulator Brassicaceae. New Phytol. 217, 194–205. doi: 10.1111/nph.14838

Elrashidi, M. A., Adriano, D. C., Workman, S. M., and Lindsay, W. L. (1987). Chemical equilibria of selenium in soils: a theoretical development. Soil Sci. 144, 141–152. doi: 10.1097/00010694-198708000-00008

Eslamiparvar, A., Hosseinifarahi, M., Amiri, S., and Radi, M. (2025). Combined bio fortification of spinach plant through foliar spraying with iodine and selenium elements. Sci. Rep. 15, 6722. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-91554-3

Fajardo, D., Schlautman, B., Steffan, S., Polashock, J., Vorsa, N., and Zalapa, J. (2014). The American cranberry mitochondrial genome reveals the presence of selenocysteine (tRNA-Sec and SECIS) insertion machinery in land plants. Gene 536, 336–343. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.11.104

Fan, Z., Jia, W., Du, A., Xia, Z., Kang, J., Xue, L., et al. (2022). Discovery of Se-containing flavone in Se-enriched green tea and the potential application value in the immune regulation. Food Chem. 394, 133468. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133468

Francini, A., Quattrini, E., Giuffrida, F., and Ferrante, A. (2023). Biofortification of baby leafy vegetables using nutrient solution containing selenium. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 103(11), 5472–5480. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.12622

Freire, B. M., Lange, C. N., Augusto, C. C., Onwuatu, F. R., Rodrigues, G. D. A. P., Pieretti, J. C., et al. (2024). Foliar application of SeNPs for rice biofortification: a comparative study with selenite and speciation assessment. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 5, 94–107. doi: 10.1021/acsagscitech.4c00613

Freire, B. M., Lange, C. N., Cavalcanti, Y. T., Seabra, A. B., and Batista, B. L. (2024). Ionomic Profile of Rice Seedlings after Foliar Application of Selenium Nanoparticles. Toxics, 12(7), 482. doi: 10.3390/toxics12070482

Gao, W., Wang, N., Qin, C., Wang, Q., Liao, Y., and Zhang, W. (2024). Identification of sulfate transporter genes in Broussonetia papyrifera and analysis of their functions in regulating selenium metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 2995.

Georgiadou, E. C., Kowalska, E., Patla, K., Kulbat, K., Smolinska, B., Leszczynska, J., et al. (2018). Influence of heavy metals (Ni, Cu, and Zn) on nitro-oxidative stress responses, proteome regulation and allergen production in basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) plants. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1–16. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00862

Gigolashvili, T. and Kopriva, S. (2014). Transporters in plant sulphur metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 422. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00442

Golubkina, N., Kharchenko, V., Moldovan, A., Antoshkina, M., Ushakova, O., Sękara, A., et al. (2024a). Effect of selenium and garlic extract treatments of seed-addressed lettuce plants on biofortification level, seed productivity and mature plant yield and quality. Plants 13, 1190. doi: 10.3390/plants13091190

Golubkina, N., Nemtinov, V., Amagova, Z., Skrypnik, L., Nadezhkin, S., Murariu, O. C., et al. (2024b). Selenium biofortification of allium species. Crops 4, 602–622. doi: 10.3390/crops4040042

Gouveia, G. C. C., Galindo, F. S., Lanza, M. G. D. B., da Rocha Silva, A. C., de Brito Mateus, M. P., da Silva, M. S., et al. (2020). Selenium toxicity stress-induced phenotypical, biochemical and physiological responses in rice plants: Characterization of symptoms and plant metabolic adjustment. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 202, 110916. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110916

González-Morales, S., Pérez-Labrada, F., García-Enciso, E. L., Leija-Martínez, P., Medrano-Macías, J., Dávila-Rangel, I. E., et al. (2017). Selenium and sulfur to produce Allium functional crops. Molecules 22, 558. doi: 10.3390/molecules22040558

Gui, J. Y., Rao, S., Huang, X., Liu, X., Cheng, S., and Xu, F. (2022). Interaction between selenium and essential micronutrient elements in plants: a systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 853, 158673. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158673

Guignardi, Z. and Schiavon, M. (2017). “Biochemistry of plant selenium uptake and metabolism,” in Selenium in plants: molecular, physiological, ecological and evolutionary aspects, Cham, Switzerland 21–34.

Guo, B., Irigoyen, S., Fowler, T. B., and Versaw, W. K. (2008). Differential expression and phylogenetic analysis suggest specialization of plastid-localized members of the PHT4 phosphate transporter family for photosynthetic and heterotrophic tissues. Plant Signal Behav. 3, 784–790. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.10.6666

Guo, Q., Ye, J., Zeng, J., Chen, L., Korpelainen, H., and Li, C. (2023). Selenium species transforming along soil–plant continuum and their beneficial roles for horticultural crops. Horticulture Res. 10, uhac270. doi: 10.1093/hr/uhac270

Guo, N., Zhang, S., Gu, M., and Xu, G. (2021). Function, transport, and regulation of amino acids: What is missing in rice? Crop J. 9, 530–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2021.04.002

Hopper, J. L. and Parker, D. R. (1999). Plant availability of selenite and selenate as influenced by the competing ions phosphate and sulfate. Plant Soil 210, 199–207. doi: 10.1023/A:1004639906245

Hu, T., Li, H. F., Li, J. X., Zhao, G. S., Wu, W. L., Liu, L. P., et al. (2018). Absorption and bio-transformation of selenium nanoparticles by wheat seedlings (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 9, 597. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00597

Hu, C., Nie, Z., Shi, H., Peng, H., Li, G., Liu, H., et al. (2023). Selenium uptake, translocation, subcellular distribution and speciation in winter wheat in response to phosphorus application combined with three types of selenium fertilizer. BMC Plant Biol. 23, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12870-023-04227-6

Hu, W., Su, Y., Yang, R., Xie, Z., and Gong, H. (2023). Effect of foliar application of silicon and selenium on the growth, yield and fruit quality of tomato in the field. Horticulturae 9, 1126. doi: 10.3390/horticulturae9101126

Huang, R., Bañuelos, G. S., Zhao, J., Wang, Z., Farooq, M. R., Yang, Y., et al. (2024b). Comprehensive evaluation of factors influencing selenium fertilization biofortification. J. Sci. Food Agric. 104, 6100–6107. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.13442

Huang, F., Chen, L., Zhou, Y., Huang, J., Wu, F., Hu, Q., et al. (2024). Exogenous selenium promotes cadmium reduction and selenium enrichment in rice: Evidence, mechanisms, and perspectives. J. Hazardous Materials 476, 135043. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.135043

Hasanuzzaman, M., Bhuyan, M. B., Raza, A., Hawrylak-Nowak, B., Matraszek-Gawron, R., Nahar, K., et al. (2020). Selenium toxicity in plants and environment: biogeochemistry and remediation possibilities. Plants, 9(12), 1711. doi: 10.3390/plants9121711

Huang, S., Gao, L., and Fu, G. (2023). Interactive effects between zinc and selenium on mineral element accumulation and fruit quality of strawberry. Agronomy 13, 2453. doi: 10.3390/agronomy13102453

Huang, Q. Q., Wang, Q., Wan, Y. N., Yu, Y., Jiang, R. F., and Li, H. F. (2017). Application of X-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy to the study of the effect of sulphur on selenium uptake and assimilation in wheat seedlings. Biol. Plantarum 61, 726–732. doi: 10.1007/s10535-016-0698-z

Ibrahim, H. and Al-Wasfy, M. (2014). The promotive impact of using silicon and selenium with potassium and boron on fruiting of Valencia orange trees grown under Minia region conditions. World Rural Obs 6, 28–36.

Ibrahim, M. and Ibrahim, H. A. (2016). Assessment of selenium role in promoting or inhibiting potato plants under water stress. J. Hortic. Sci. Ornam. Plants 8, 125–139.

Irigoyen, S., Karilsson, P. M., Kuruvilla, J., Spetea, C., and Versaw, W. K. (2011). The sink-specific plastidic phosphate transporter PHT4;2 influences starch accumulation and leaf size in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 157, 1765–1777. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.181925

Jones, G. D., Droz, B., Greve, P., Gottschalk, P., Poffet, D., McGrath, S. P., et al. (2017). Selenium deficiency risk predicted to increase under future climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 2848–2853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611576114

Kang, Y., Ming, J., Fu, W., Long, L., Wen, X., Zhang, Q., et al. (2024). Selenium fertilizer improves microbial community structure and diversity of Rhizospheric soil and selenium accumulation in tomato plants. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 55, 1430–1444. doi: 10.1080/00103624.2024.2315931

Kataoka, T., Watanabe-Takahashi, A., Hayashi, N., Ohnishi, M., Mimura, T., Buchner, P., et al. (2004). Vacuolar sulphate transporters are essential determinants controlling internal distribution of sulfate in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 2693–2704. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.023960

Kikkert, J. and Berkelaar, E. (2013). Plant uptake and translocation of inorganic and organic forms of selenium. Arch. Environ. Con. Tox 65, 458–465. doi: 10.1007/s00244-013-9926-0

Kipp, A. P., Strohm, D., Brigelius-Floh, E. R., Schomburg, L., Bechthold, A., LeschikBonnet, E., et al. (2015). Revised reference values for selenium intake. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 32, 195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2015.07.005

Knappe, S., Flügge, U. I., and Fischer, K. (2003). Analysis of the plastidic phosphate translocator gene family in Arabidopsis and identification of new phosphate translocator-homologous transporters, classified by their putative substrate-binding site. Plant Physiol. 131, 1178–1190. doi: 10.1104/pp.016519

König, J., Muthuramalingam, M., and Dietz, K.-J. (2012). Mechanisms and dynamics in the thiol/disulfide redox regulatory network: transmitters, sensors and targets. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15(3), 261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.12.002

Kumar, P., Kumar, K. M., and Kumar, A. (2011). Speciation of selenium in groundwater: seasonal variations and redox transformations. Appl. Geochemistry 26, 542–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.05.013

Kolbert, Z., Molnár, Á., Feigl, G., and Van Hoewyk, D. (2019). Plant selenium toxicity: Proteome in the crosshairs. Journal of plant physiology, 232, 291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2018.11.003

Kushwaha, A., Goswami, L., Lee, J., Sonne, C., Brown, R. J., Kim, K. H., et al. (2022). Selenium in soil-microbe-plant systems: Sources, distribution, toxicity, tolerance, and detoxification. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 52(13), 2383–2420. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2021.1883187

Lalithya, K., Bhagya, H., and Choudhary, R. (2014). Response of silicon and micronutrients on fruit character and nutrient content in leaf of sapota. Biolife 2, 593–598.

Lan, L., Feng, Z., Liu, X., and Zhang, B. (2024). The roles of essential trace elements in T cell biology. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 28, e18390. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.18390

Lanza, M. G. D. B. (2024). Genotypic variability of cowpea (Vigna Unguiculata (L.) Walp) And selenium uptake for determining agronomic biofortification strategies to combat hidden hunger. Thesis (Doctorate in Agronomy) – Universidade Estadual Paulista "Julio de Mesquita Filho", Jaboticabal.

Lanza, M. G. D. B. and Reis, A. R. D. (2021). Roles of selenium in mineral plant nutrition: ROS scavenging responses against abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol. Bioch 164, 27–43. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.04.026

Li, H. F., McGrath, S. P., and Zhao, F. J. (2008). Selenium uptake, translocation and speciation in wheat supplied with selenate or selenite. New Phytol. 178, 92–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02343.x

Li, Y. Y., Yu, S. H., and Zhou, X. B. (2019). Effects of phosphorus on absorption and transport of selenium in rice seedlings. Environ. Sci. pollut. Res. 26, 13755–13761. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2690-y

Li, Q., Zheng, F., Huang, X., Cai, M., Li, Y., and Liu, H. (2024). Selenium utilization, distribution and its theoretical biofortification enhancement in rice granary of China. Agronomy 14, 2596. doi: 10.3390/agronomy14112596

Li, M., Zhou, S., Zhou, C., Peng, Y., Wen, X., Cong, W., et al. (2025). Unlocking the potential of selenium (Se) bio-fortification and optimal food processing of barely grains on the alleviation of Se-deficiency in highland diets. J. Food Composition Anal. 142, 107436. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2025.107436

Liao, Q., Xing, Y., Li, A. M., Liang, P. X., Jiang, Z. P., Liu, Y. X., et al. (2024). Enhancing selenium biofortification: strategies for improving soil-to-plant transfer. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 11, 148. doi: 10.1186/s40538-024-00672-z

Lidon, F. C., Oliveira, K., Galhano, C., and Galhano, C. (2019). Selenium biofortification of rice through foliar application with selenite and selenate. Exp. Agr 55, 528–542. doi: 10.1017/S0014479718000157

Lima, L. W., Pilon-Smits, E. A. H., and Schiavon, M. (2018). Mechanisms of selenium hyperaccumulation in plants: a survey of molecular, biochemical and ecological cues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj 1862, 2343–2353. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2018.03.028

Lin, Y., Cao, S., Wang, X., Liu, Y., Sun, Z., Zhang, Y., et al. (2024). Foliar application of sodium selenite affects the growth, antioxidant system, and fruit quality of strawberry. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1449157. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1449157

Liu, K., Chen, F., Zhao, Y., Gu, Z., and Yang, H. (2011). Selenium accumulation in protein fractions during germination of Se-enriched brown rice and molecular weights distribution of Se-containing proteins. Food Chem. 127, 1526–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.02.010

Liu, T. Y., Huang, T. K., Yang, S. Y., Hong, Y. T., Huang, S. M., Wang, F. N., et al. (2016). Identification of plant vacuolar transporters mediating phosphate storage. Nat. Commun. 7, 11095. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11095

Liu, Y., Tian, X., Liu, R., Liu, S., and Zuza, A. V. (2021a). Key driving factors of selenium enriched soil in the low-se geological belt: a case study in red beds of Sichuan Basin, China. Catena 196, 104926. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2020.104926

Liu, H., Zhang, Y., Zhang, L., Liu, Y., Chen, Y., and Shi, Y. (2025). Nano-selenium strengthens potato resistance to potato scab induced by Streptomyces spp., increases yield, and elevates tuber quality by influencing rhizosphere microbiomes. Front. Plant Sci. 16, 1523174. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1523174

Liu, R., Zhao, L., Li, J., Zhang, C., Lyu, L., Man, Y. B., et al. (2023a). Influence of exogenous selenomethionine and selenocystine on uptake and accumulation of Se in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L. cv. Xinong 979). Environ. Sci. pollut. Res. 30, 23887–23897. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-23916-7

Lopez-Arredondo, D. L., Leyva-Gonzalez, M. A., Gonzalez-Morales, S. I., LopezBucio, J., and Herrera-Estrella, L. (2014). Phosphate nutrition: improving low-phosphate tolerance in crops. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65, 95–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-035949

Lyu, C., Qin, Y., Zhao, Z., and Liu, X. (2021). Characteristics of selenium enrichment and assessment of selenium bioavailability using the diffusive gradients in thin-films technique in seleniferous soils in Enshi, Central China. Environ. pollut. 273, 116507. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116507

Ma, Y., Huang, X., Du, H., Yang, J., Guo, F., and Wu, F. (2024). Impacts, causes and biofortification strategy of rice selenium deficiency based on publication collection. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 169619. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169619

Machado, B. Q. V., Pereira, B. D. J., Rezende, G. F., and Cecílio Filho, A. B. (2024). Onion quality and yield after agronomic biofortification with selenium. Chilean J. Agric. Res. 84, 372–379. doi: 10.4067/S0718-58392024000300372

Matich, A. J., McKenzie, M. J., Lill, R. E., Brummell, D. A., McGhie, T. K., Chen, R. K.-Y., et al. (2012). Selenoglucosinolates and their metabolites produced in Brassica spp. fertilised with sodium selenate. Phytochemistry 75, 140–152. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.11.021

Matich, A. J., McKenzie, M. J., Lill, R. E., McGhie, T. K., Chen, R. K. Y., and Rowan, D. D. (2015). Distribution of selenoglucosinolates and their metabolites in Brassica treated with sodium selenate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 63, 1896–1905. doi: 10.1021/jf505963c

McNeal, J. M. and Balistrieri, L. S. (2015). Geochemistry and occurrence of selenium: an overview. Selenium Agric. Environ. 23, 1–13. doi: 10.2136/sssaspecpub23.c1

Mikkelsen, R. L., Page, A. L., and Bingham, F. T. (1989). “Factors affecting selenium accumulation by agricultural crops,” in Selenium in Agriculture and the Environment. Ed. Jacobs, J. W. (Soil Science Society of America & American Society of Agronomy, Madison, USA), 65–94.

Młodzińska, E. and Zboińska, M. (2016). Phosphate uptake and allocation–a closer look at Arabidopsis thaliana L. and Oryza sativa L. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1198. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01198

Mrština, T., Praus, L., Száková, J., Kaplan, L., and Tlustoš, P. (2024). Foliar selenium biofortification of soybean: The potential for transformation of mineral selenium into organic forms. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1379877. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1379877

Nakamaru, Y. M. and Altansuvd, J. (2014). Speciation and bioavailability of selenium and antimony in non-flooded and wetland soils: a review. Chemosphere 111, 366–371. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.04.024

Namorato, F. A., Cipriano, P. E., Zauza, S. B., Benevenute, P. A. N., Araújo, S. N. D., Correia, R. F. R., et al. (2025). Selenium biofortification with Se-Enriched urea and Se-enriched ammonium sulfate fertilization in different common bean genotypes. Agronomy 15, 440. doi: 10.3390/agronomy15020440

Nie, X., Luo, D., Ma, H., Wang, L., Yang, C., Tian, X., et al. (2024). Different effects of selenium speciation on selenium absorption, selenium transformation and cadmium antagonism in garlic. Food Chem. 443, 138460. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.138460

Nwachukwu, I. D. and Aluko, R. E. (2018). Physicochemical and emulsification properties of flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum) albumin and globulin fractions. Food Chem. 255, 216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.02.068

Ogunsuyi, O. B., Odeyemi, I. A., Adedayo, B. C., and Oboh, G. (2025). Selenium biofortification of solanum vegetables modulates their phytoconstituents, agronomic and antioxidant properties. Food Chem. Int. doi: 10.1002/fci2.70032

Ohno, M., Uraji, M., Shimoishi, Y., Mori, I. C., Nakamura, Y., and Murata, Y. (2012). Mechanisms of the selenium tolerance of the Arabidopsis thaliana knockout mutant of sulfate transporter SULTR1;2. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 76, 993–998. doi: 10.1271/bbb.111000

Okumura, S., Mitsukawa, N., Shirano, Y., and Shibata, D. (1998). Phosphate transporter gene family of Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 5, 261–269. doi: 10.1093/dnares/5.5.261

Ouerdane, L., Aureli, F., Flis, P., Bierla, K., Preud'homme, H., Cubadda, F., et al. (2013). Comprehensive speciation of low-molecular weight selenium metabolites in mustard seeds using HPLC-electrospray linear trap/orbitrap tandem mass spectrometry. Metallomics 5, 1294–1304. doi: 10.1039/c3mt00113j

Owusu-Sekyere, A., Kontturi, J., and Hajiboland, R. (2013). Influence of selenium (Se) on carbohydrate metabolism, nodulation and growth in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Plant Soil 373, 541–552. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1815-9

Oztekin, Y. and Buyuktuncer, Z. (2024). Agronomic biofortification of plants with iodine and selenium: a potential solution for iodine and selenium deficiencies. Biol. Trace Element Res. 203, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12011-024-04346-7

Peak, D. and Sparks, D. L. (2002). Mechanisms of selenate adsorption on iron oxides and hydroxides. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 1460–1466. doi: 10.1021/es0156643

Pilon-Smits, E. A. H., De Souza, M. P., Hong, G., Amini, A., Bravo, R. C., Payabyab, S. T., et al. (1999). Selenium volatilization and accumulation by twenty aquatic plant species. Am. Soc. Agronomy Crop Sci. Soc. America Soil Sci. Soc. America 28, 1011–1018. doi: 10.2134/jeq1999.00472425002800030035x

Pivato, M., Fabrega-Prats, M., and Masi, A. (2014). Low-molecular-weight thiols in plants: functional and analytical implications, Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 560, 83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.07.018

Poirier, Y. and Bucher, M. (2002). Phosphate transport and homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Arabidopsis Book 1, e0024. doi: 10.1199/tab.0024

Profico, C. M., Hassanpour, M., Hazrati, S., Ertani, A., Mollaei, S., and Nicola, S. (2025). Sodium selenate Biofortification of Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) and Peppermint (Mentha × piperita L.) plants grown in a Floating System under salinity stress. J. Agric. Food Res. 21, 101842. doi: 10.1016/j.jafr.2025.101842

Qi, Z., Duan, A., and Ng, K. (2024). Selenosugar, selenopolysaccharide, and putative selenoflavonoid in plants. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 23, e13329. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.13329

Qin, H. B., Zhu, J. M., and Su, H. (2012). Selenium fractions in organic matter from se-rich soils and weathered stone coal in selenosis areas of China. Chemosphere 86, 626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.10.055

Qu, L., Xu, J., Dai, Z., Mohamed, A., and Huang, W. (2023). Selenium in soil-plant system: transport, detoxification and bioremediation. J. Hazard Mater 452, 131272. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131272

Radawiec, A., Szulc, W., and Rutkowska, B. (2021). Effect of fertilization with selenium on the content of selected microelements in spring wheat grain. J. Elem 26, 1025–1036. doi: 10.5601/jelem.2021.26.4.2206

Ramos, S. J., Rutzke, M. A., Hayes, R. J., Faquin, V., Guilherme, L. R. G., and Li, L. (2011). Selenium accumulation in lettuce germplasm. Planta 233, 649–660. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1323-6

Ranawake, L., Seneweera, S., and Pathirana, R. (2025). Selenium biofortification as a sustainable solution to combat global selenium malnutrition. doi: 10.20944/preprints202501.1935.v1

Rausch, C. and Bucher, M. (2002). Molecular mechanisms of phosphate transport in plants. Planta 216, 23–37. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0921-3

Rayman, M. P. (2012). Selenium and human health. Lancet 379, 1256–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61452-9

Rayman, M. P., Infante, H. G., and Sargent, M. (2008). Food-chain selenium and human health: spotlight on speciation. Br. J. Nutr. 100, 238–253. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508922522

Reich, H. J. and Hondal, R. J. (2016). Why nature chose selenium. ACS Chem. Biol. 11, 821–841. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00031

Ren, L., Jiang, W., Geng, J., Yu, T., Ji, G., Zhang, X., et al. (2023). Sulfur levels regulate the absorption and utilization of selenite in rapeseed (Brassica napus). Environ. Exp. Bot. 213, 105454. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2023.105454

Ren, H., Li, X., Guo, L., Wang, L., Hao, X., and Zeng, J. (2022). Integrative transcriptome and proteome analysis reveals the absorption and metabolism of selenium in tea plants [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.848349

Ribeiro, D. M., Silva Júnior, D. D., Cardoso, F. B., Martins, A. O., Silva, W. A., Nascimento, V. L., et al. (2016). Growth inhibition by selenium is associated with changes in primary metabolism and nutrient levels in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 39, 2235–2246. doi: 10.1111/pce.12783

Rouached, H., Wirtz, M., Alary, R., Hell, R., Arpat, A. B., Davidian, J.-C., et al. (2008). Differential regulation of the expression of two high-affinity sulfate transporters, SULTR1.1 and SULTR1.2, in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 147, 897–911. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.118612

Sandholm, M., Oksanen, H. E., and Pesonen, L. (1973). Uptake of selenium by aquatic organisms. Limnol Oceanogr 18, 496–498. doi: 10.4319/lo.1973.18.3.0496

Sarwar, N., Akhtar, M., and Kamran, M. A. (2020). Selenium biofortification in food crops: key mechanisms and future perspectives. J. Food Compos. Anal. 93, 103615. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2020.103615

Schiavon, M., Lima, L. W., Jiang, Y., and Hawkesford, M. J. (2017). “Effects of selenium on plant metabolism and implications for crops and consumers,” in Selenium in Plants: Molecular, Physiological, Ecological and Evolutionary Aspects. Eds. Pilon-Smits, E. A. H., Winkel, L. H. E., and Lin, Z.-Q. (Springer, Cham, Switzerland), 275–357.

Schiavon, M., Pilon, M., Malagoli, M., and Pilon-Smits, E. A. H. (2015). Exploring the importance of sulphate transporters and ATPsulphurylases for selenium hyperaccumulation – comparison of Stanleya pinnata and Brassica juncea (Brassicaceae). Front. Plant Sci. 6, 2. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00002

Schomburg, L. and Arnér, E. S. J. (2017). “Selenium metabolism in herbivores and higher trophic levels including mammals,” in Selenium in Plants: Molecular, Physiological, Ecological and Evolutionary Aspects. Eds. Pilon-Smits, E. A. H., Winkel, L. H. E., and Lin, Z.-Q. (Springer, Cham, Switzerland), 123–139.

Semenova, N. A., Nikulina, E. A., Tsirulnikova, N. V., Godyaeva, M. M., Uyutova, N. I., Baimler, I. V., et al. (2024). Application of 2-Iminoselenazolidin-4-Ones (ISeA) for Beta vulgaris L. and Brassica rapa L. Plants Se-Biofortification. Agron. 14, 1407. doi: 10.3390/agronomy14071407

Shao, S. X., Mi, X. B., Ouerdane, L., Lobinski, R., García-Reyes, J. F., Molina-Díaz, A., et al. (2014). Quantification of Se-methylselenocysteine and its γ-glutamyl derivative from naturally Se-enriched green bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) after HPLC-ESI-TOF-MS and orbitrap MSn-based identification. Food Anal. Methods 7, 1147–1157. doi: 10.1007/s12161-013-9728-z

Shibagaki, N., Rose, A., McDermott, J. P., Fujiwara, T., Hayashi, H., Yoneyama, T., et al. (2002). Selenate-resistant mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana identify Sultr1;2, a sulfate transporter required for efficient transport of sulfate into roots. Plant J. 29, 475–486. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7412.2001.01232.x

Shinmachi, F., Buchner, P., Stroud, J. L., Parmar, S., Zhao, F. J., McGrath, S. P., et al. (2010). Influence of sulfur deficiency on the expression of specific sulfate transporters and the distribution of sulfur, selenium, and molybdenum in wheat. Plant Physiol. 153, 327–336. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.153759

Shiriaev, A., Brizzolara, S., Sorce, C., Meoni, G., Vergata, C., Martinelli, F., et al. (2023). Selenium biofortification impacts the tomato fruit metabolome and transcriptional profile at ripening. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 13554–13565. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c02031