- Department of Horticulture, Division of Applied Life Science (BK21 Four Program), Institute of Agriculture and Life Science, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, Republic of Korea

Plant viruses represent a major challenge to agricultural systems, threatening global food security amid a rising population. Specifically, pepper cultivation (Capsicum annuum L.) is often hindered by various viral diseases, with more than 60 viruses identified as affecting pepper plants. The most efficient strategy for controlling viral diseases is the development of resistant cultivars of peppers. A comprehensive understanding of complex interactions between plant defense mechanisms and the strategies employed by viruses to evade these defenses, coupled with host factors that facilitate viral replication and movement, is essential for developing resistant cultivars. Natural antiviral defense mechanisms in plants are well characterized and include resistance genes, RNA silencing, autophagy-mediated degradation, translational repression, and resistance to viral movement. Recent advances in next-generation sequencing (NGS), genome-wide association studies (GWAS), high-density genotyping platforms and gene-editing tools such as CRISPR/Cas have accelerated the identification of resistance loci and key host factors involved in viral pathogenesis. This review summarizes current molecular and genomic insights into virus–host interactions in Capsicum spp., highlighting their role in advancing marker-assisted selection (MAS) and genomic-assisted breeding. The integration of molecular markers and genome editing into breeding pipelines offers new opportunities for developing durable, broad-spectrum viral resistance in peppers, ultimately supporting sustainable crop production and agricultural resilience.

1 Introduction

Plant viruses pose a significant threat to global food security and ecosystem services, damaging crops and cropping systems and resulting in an estimated annual global yield loss of approximately $30 billion and contributing to nearly half of all emerging plant diseases (Jones, 2021). Over 2,100 plant virus species have been officially recognized by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (Walker et al., 2021). The top ten viruses recognized for their widespread prevalence and significant global economic impact include Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV), Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), Potato virus Y (PVY), Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV), African cassava mosaic virus (ACMV), Plum pox virus (PPV), Brome mosaic virus (BMV), and Potato virus X (PVX) (Scholthof et al., 2011).

Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) holds significant economic value worldwide as a vegetable crop, primarily consumed for its fruits either in fresh or dried form, or utilized in the production of spicy condiments (Hernández-Pérez et al., 2020). According to FAOSTAT (2024), global pepper production increased steadily from 1.8 million tons in 1994 to 4.9 million tons in 2022, in both fresh and dried forms, highlighting its commercial significance (Kim et al., 2025). However, the commercial cultivation of pepper is significantly impacted by various environmental stresses, encompassing both biotic and abiotic factors (Kang et al., 2020; Kwon et al., 2021). Pepper plants encounter numerous plant pathogens, such as viruses, fungi, bacteria, nematodes, oomycetes, and viroids (Kang et al., 2022). The pepper cultivation across numerous regions worldwide is persistently hampered by a wide range of viral diseases. Approximately 68 viruses have been reported to infect pepper plants (Pernezny et al., 2003). Among them, about 20 virus species including both DNA and RNA viruses are notorious for causing substantial damage to pepper crops (Moury and Verdin, 2012). RNA viruses known to infect pepper plants include those from the genera Cucumovirus, Tobamovirus, Polerovirus, Potyvirus and Crinivirus (Kenyon et al., 2014). Among the DNA viruses, members of the genus Begomovirus, in the family Geminiviridae, are most commonly reported in pepper.

Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites that depend entirely on the host cellular machinery for replication and spread. Successful viral infection requires the coordinated manipulation of several aspects of the host cell biology, such as those that allow the virus to replicate its genome, suppress or evade plant defense mechanisms, and accurately transport the virus within and between cells (Medina-Puche and Lozano-Durán, 2019). The most well studied natural mechanisms of plant antiviral defense is mediated by resistance (R) genes (innate immunity), RNA silencing, autophagy-mediated degradation, translational repression, and resistance to virus movement (Akhter et al., 2021). The integration of diverse resistance genes via breeding initiatives, coupled with the application of genetic engineering and genome editing techniques like CRISPR/Cas technologies, shows significant potential in the development of economically valuable pepper crops, with enhanced resistance to viruses. Moreover, the advent of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies has facilitated more effective molecular breeding of pepper to combat both abiotic and biotic stresses, including devastating viral infections (Lee and Yeom, 2023; Kim et al., 2024b; Shilpha et al., 2024; Kwon et al., 2024a, Kwon et al., 2024b). These genomic resources facilitate the deployment of marker-assisted selection (MAS) and genomic selection (GS) for accelerating resistance breeding in pepper. Furthermore, the establishment of pangenomes, together with the use of specialized genetic populations such as recombinant inbred lines (RILs), introgression lines (ILs), and multiparent advanced generation inter-cross (MAGIC) populations, provides valuable frameworks for dissecting complex resistance traits and stacking multiple resistance genes to achieve durable and broad-spectrum viral resistance in Capsicum spp (Zohoungbogbo et al., 2024). This review provides a comprehensive overview of viral infection process and antiviral defense mechanisms in peppers, taking into account of viruses that commonly infect pepper crops. It also highlights recent molecular and genomic advances that offer new strategies for enhancing viral resistance in pepper breeding programs.

2 Viral factors contributing to pathogenesis in pepper

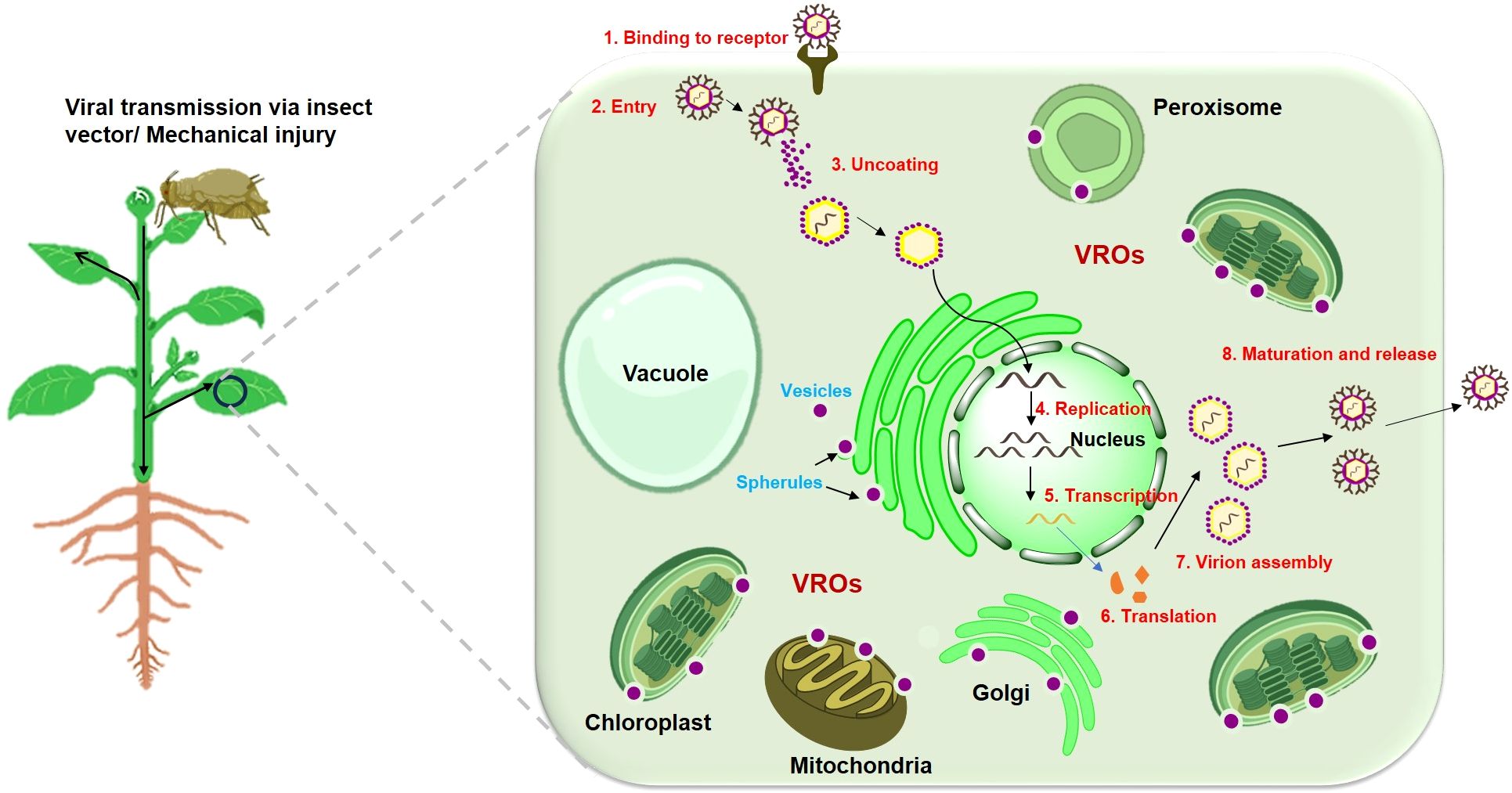

Viruses, possessing a parasitic nature, have evolved adeptness in manipulating and hijacking cellular components, such as host proteins and organelles, to enhance their replication. Therefore, understanding how viruses manipulate cellular machinery to their infection cycles is crucial for developing plant varieties resistant to viral attacks. Upon entering the host cell, the viral genetic material – either DNA or RNA – serves as a template for transcription and translation processes, leading to the production of new viral genomes and proteins required for replication. While translation and replication selection occur in the cytoplasm, the actual replication process is confined to intracellular membranes, including chloroplast (Bwalya and Kim, 2023). Viral membrane proteins, direct the modification of host cellular membranes, leading to the formation of viral replication organelles/complexes (VROs/VRCs), the specialized membrane-bound viral replication compartments that facilitate the replication of the viral genome (Jovanović et al., 2023). These viral replication complexes are thought to restrict the viral replication process to a particular safe microenvironment that shields the replicating and progeny viruses from being attacked by host antiviral responses such as RNA silencing. To generate VROs, viruses typically target and remodel specific membrane-bound organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum, chloroplasts, tonoplasts, peroxisomes, and mitochondria (Figure 1). Two categories of viral replication organelles or factories have been identified based on their morphology. These include spherules, which are invaginations of organelle boundary membranes, and tubular or vesicular organelles formed by host membrane protrusions (Nguyen-Dinh and Herker, 2021).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of viral transmission and replication within the plant cell. Virus enters the plant cell through an insect vector or mechanical injury. Once entered, the viral particle sheds its protective protein coat (capsid), releasing the viral genome (RNA or DNA) into the cytoplasm. Then, the viral genome is replicated using the host’s cellular machinery. For RNA viruses, replication occurs in the cytoplasm, whereas DNA viruses replicate using the plant’s nuclear machinery. Viral replication often involves the formation of specialized compartments or organelles to facilitate the replication process known as viral replication organelles (VROs). Specialized structures such as spherules and vesicles, often arise from the invagination of host cell membranes, such as the endoplasmic reticulum, chloroplast, mitochondria or peroxisomal membranes to facilitate viral replication and assembly. The viral genome then undergoes transcription and translation to produce viral proteins, including structural proteins, movement proteins, and proteins that suppress the plant's immune response. Once sufficient viral genomes and structural proteins are synthesized, they assemble into new viral particles (virions) in the cytoplasm. After infecting initial cells, the virus can spread systemically throughout the plant via the phloem, reaching distant tissues and organs.

Nonsynonymous substitutions, which lead to amino acid changes in viral proteins, play a critical role in the evolution of viral pathogenicity. These mutations can profoundly affect the structure and function of viral proteins, thereby directly influencing their interactions with both viral and host factors. Based on the genetic variety brought about by amino acid alterations, plant viruses vary in their pathogenicity and degree of symptom severity on distinct host plants. For instance, the 13 Korean isolates of PepMoV were classified into two groups based on genetic variation, symptom severity, and pathogenicity on various host plants (Kim et al., 2008, Kim et al., 2009). By analyzing the ratio of synonymous (dS) to non-synonymous (dN) base substitutions in the P1 and 6K2 genes, as well as the amino acid (aa) variation that the 6K2 gene encodes, Kim et al. (2009) suggested that these genes may have a role in the pathogenicity and host specificity of PepMoV. Five resistance genes (L1, L1a, L2, L3, and L4) on chromosome 11 located at the L locus of the genus Capsicum, exhibits HR-mediated resistance against tobamoviruses such as PMMoV. Genda et al (2007) found that the L4 gene-mediated resistance in Capsicum chacoense was overcome by two amino acid substitutions in the coat protein of PMMoV: glutamine (Gln) to arginine (Arg) at position 46 and glycine (Gly) to lysine (Lys) at position 85.

Specific amino acid substitutions are critical for systemic infection of CMV-Fny and CMV-P1 in peppers (Kang et al., 2012). The helicase domain of CMV RNA1 was identified as the key determinant of infection and virulence in peppers with Cmr1 gene, which conferred resistance to CMV-Fny but not CMV-P1. Four residues (positions 865, 896, 957, and 980) in the CMV-P1 helicase domain were crucial for systemic infection, replication, and cell-to-cell movement. Subsequently, host genes such as formate dehydrogenase and calreticulin-3 precursor were identified to be interacting with the CMV-P1 helicase domain and crucial for CMV-P1 infection (Choi et al., 2016). Similarly, Han et al. (2020) reported four amino acid differences between PMMoV isolates ZJ1 and ZJ2 causing distinct chlorosis in pepper from Zhejiang, China. An Asn/Asp substitution in the coat protein determined chlorosis and localization: CP20Asp at the cell periphery, CP20Asn in chloroplasts. Fang et al. (2022) showed that specific residues in the HC-Pro and NIb-CP regions of PepMoV influence virus accumulation, movement, and symptoms. Tyrosine, glycine, and leucine at positions 360, 385, and 527 in HC-Pro enhanced accumulation/movement, while valine at position 2773 of NIb was crucial for symptom development. The CMV strain involved in mixed infection with tospoviruses is likely responsible for chlorosis in Indian hot pepper, as indicated by the amino acid substitution of Ser129 over conserved Pro129 in the coat protein (Vinodhini et al., 2021).

3 Anti-viral defense mechanisms in Capsicum species

In order to evade viral invasion, plants have evolved complex defense mechanisms that include RNA interference, RNA stability regulation, autophagy, protein breakdown via ubiquitination, hypersensitive response (HR), resistance responses mediated by R genes, and the induction of systemic acquired resistance (Lozano-Durán, 2024; Wei et al., 2024; Sharma et al., 2025). Plant resistance against viral disease is generally categorized into three types: non-host resistance, host resistance, and systemic acquired resistance (SAR) (Kang et al., 2005; Rai et al., 2022). Non-host resistance operates at the species level, where all members resist infection by a particular virus, often due to basal defenses, though the exact mechanisms remain unclear. Host resistance, also known as specific or cultivar resistance, involves specific genes in the plant that confer resistance to certain viruses, playing a crucial role in plant breeding. SAR occurs when plants activate defense mechanisms in response to pathogen exposure, leading to systemic protection and the activation of pathogenesis-related genes that produce antimicrobial compounds (Tian et al., 2024). This response is closely associated with the action of salicylic acid (SA) and can also be triggered by insect herbivory, thereby enhancing overall plant resistance.

3.1 Natural resistance mechanisms

Viral infection in plants involves several stages: entry into cells, uncoating of nucleic acid, translation of viral proteins, replication of nucleic acid, assembly of new virions, movement between cells, and spread to other plants (Figure 1). To prevent viral invasion, plants block viral movement at the cellular level, with some resistance mechanisms targeting viral replication or movement stages.

3.1.1 Restriction of viral multiplication

Resistance at the single cell level, known as extreme resistance (ER) or cellular immunity, prevents virus replication within initially infected cells. The C. annuum cultivar 'Perennial' exhibited limited CMV multiplication in inoculated leaves, with a lower replication rate compared to the cultivars 'Vania' and 'Yolo Wonder' (Nono-Womdim et al., 1993; Lapidot et al., 1997). Additionally, 'Perennial' demonstrated resistance to other viruses, including various potyviruses (Caranta et al., 1996).

3.1.2 Restriction of viral movement

When viruses infect plants, they spread from initially infected cells to neighboring ones and, for long-distance movement, through bundle sheath cells, phloem, and sieve elements. Plasmodesmata regulate both cell-to-cell and systemic movement. Plants counter by restricting viral spread, involving specific viral and host factors (Carrington et al., 1996). Resistance to CMV may involve limited entry, uncoating, restricted multiplication, or impaired long-distance movement, influenced by environment, CMV isolates, and host genetics (Chaim et al., 2001). In C. annuum varieties “Vania,” “Milord,” “L57,” and “L113,” resistance mainly limits long-distance CMV movement and is partial (Mihailova et al., 2013). Similarly, Indian chili “Perennial,” considered tolerant or partially resistant, restricts entry, reduces multiplication, and prevents systemic spread (Nono-Womdim et al., 1993; Caranta et al., 1997). In C. annuum cv. Avelar, PepMoV systemic movement is normally restricted but collapses under CMV co-infection, enabling PepMoV accumulation and systemic spread (Guerini and Murphy, 1999). In pepper, pvr1 (eIF4E) was linked to PVY cell-to-cell movement (Ruffel et al., 2002). C. frutescens “BG2814-6” hinders viral replication and cell-to-cell spread (Grube et al., 2000), while C. annuum “Bukang” blocks CMV movement from epidermal to mesophyll cells (Kang et al., 2010).

3.2 Dominant resistance genes

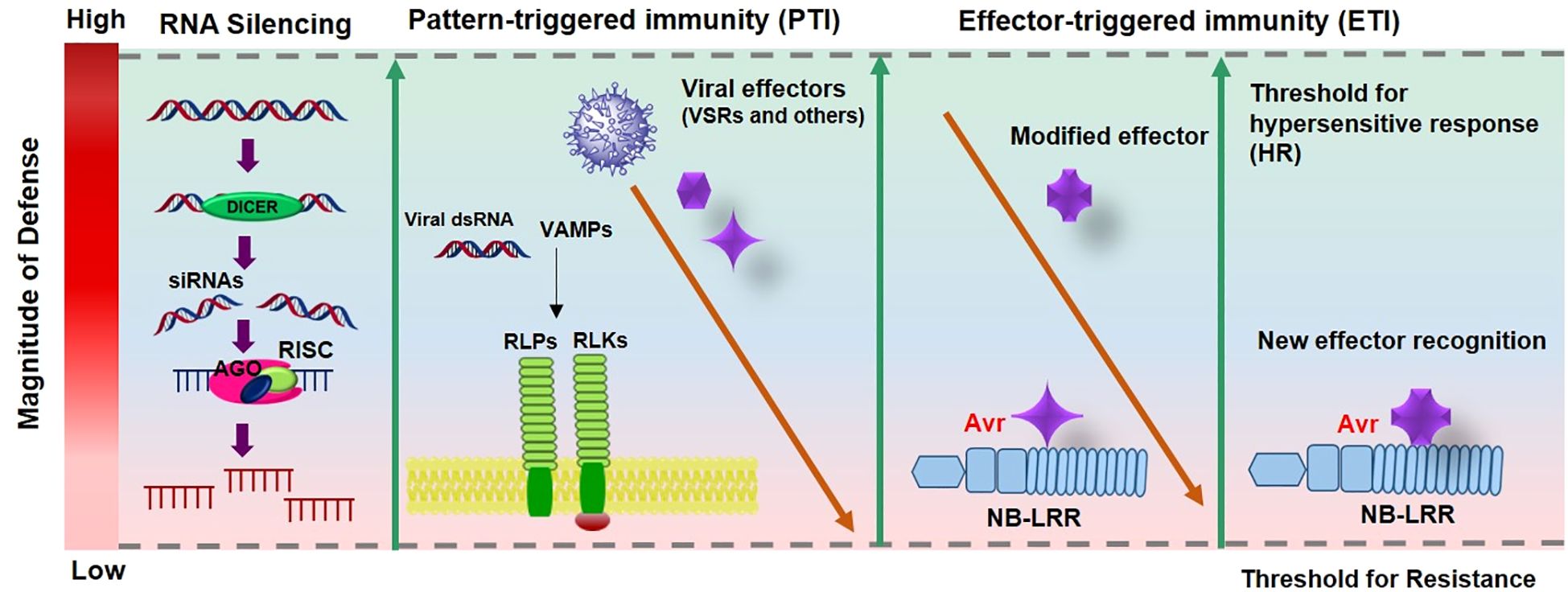

Dominant plant resistance (R) genes play a crucial role in antiviral defense, most of which encode nucleotide-binding site (NBS) and leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domains that enable recognition of pathogen-derived molecules and activation of defense responses (Collier and Moffett, 2009). In Capsicum and other plants, antiviral defense operates through two primary immune layers (Figure 2). The first layer, pattern-triggered immunity (PTI), is initiated by the perception of virus-associated molecular patterns (VAMPs) such as viral double-stranded RNAs by DICER-like proteins or membrane-bound pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) including receptor-like kinases (RLKs) and receptor-like proteins (RLPs). This basal immune response restricts viral replication and movement but is often suppressed by viral suppressors of RNA silencing (VSRs), which counteract RNA-based antiviral mechanisms and PTI responses.

Figure 2. The zig-zag model [adopted from Jones and Dangl et al. (2006) and Piau and Schmitt-Keichinger, 2023)] illustrates the evolutionary combat between plants and viruses. In this model, silencing is often seen as a form of pattern-triggered immunity (PTI), where DICER like proteins detect Virus-associated molecular patterns, VAMPs, typically viral double-stranded RNAs. Additionally, PTI can play a role in antiviral defense through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), functioning independently of RNA silencing. This initial defense is relatively weak and can be countered by viral effectors, including viral suppressors of RNA silencing (VSRs). A second, stronger layer of defense involves the specific recognition of viral effectors by NB-LRR proteins encoded by resistance (R) genes, leading to effector-triggered immunity (ETI). If strong and rapid enough, ETI can trigger hypersensitive cell death (HR). However, viruses may evolve modified effectors to evade recognition, prompting plants to develop new NB-LRRs capable of detecting the altered effectors and restoring ETI.

The second, more specific layer, effector-triggered immunity (ETI), is activated when intracellular NB-LRR proteins recognize particular viral effectors (Avr factors). This recognition elicits a strong defense reaction, typically the hypersensitive response (HR), which confines viral spread by inducing localized cell death (Jones and Dangl, 2006). However, viruses continuously evolve modified effectors that escape recognition, leading to a dynamic co-evolutionary arms race where plants in turn develop new NB-LRR variants capable of detecting altered viral effectors and reinstating ETI (Piau and Schmitt-Keichinger, 2023).

In pepper, Pvr4, Pvr7, and Pvr9 induce HR against potyviruses (Murphy et al., 1998; Janzac et al., 2009; Tran et al., 2015). The Pvr7 from C. chinense PI159236 and Pvr4 from C. annuum ‘CM334’ provide ER to PVY and PepMoV (Venkatesh et al., 2018) (Table 1). The Pvr4 encodes a coiled-coil nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (CNL) protein and confers resistance to PepMoV (Kim et al., 2017). The NIb protein of several potyviruses, including PepMoV, acts as an avirulence factor for Pvr4, inducing HR, whereas Tobacco etch virus (TEV) NIb does not due to lower sequence similarity (Kim et al., 2015). The Pvr9, similar to Solanum bulbocastanum Rpi-blb2, was identified via Agrobacterium transient expression on chromosome 6 and encodes a 1298-aa CNL protein. PepMoV slightly increases Pvr9 expression in resistant ‘CM334’ but reduces it in susceptible ‘Floral Gem’. Both Pvr4 and Pvr9 mediate HR to PepMoV NIb (Tran et al., 2014, Tran et al, 2015). Resistance to PepMoV is linked to Pvr4 and Pvr7; high-resolution mapping revealed Pvr7 in C. annuum ‘9093’ is identical to Pvr4 from ‘CM334’, representing the same locus (Venkatesh et al., 2018). Tsw, a dominant gene from C. chinense, confers HR to most TSWV isolates and is allelic with Pvr4 at chromosome 10, sharing highly similar structures despite recognizing different viral effectors. The TSWV-NSs protein acts as a viral effector that triggers HR. The Tsw gene encodes CNL protein (Kim et al., 2017).

Capsicum spp. possess a series of L resistance genes that confer defense against Tobamovirus species and have been strategically incorporated into commercial cultivars to mitigate viral infections. These L genes encode NB-LRR immune receptors that mediate effector-triggered immunity (ETI) by recognizing specific amino acid motifs in viral coat proteins. This recognition induces conformational activation of the receptor, triggering downstream defense responses such as ion fluxes, reactive oxygen species (ROS) bursts, and transcriptional activation of defense genes, culminating in a localized hypersensitive response (HR) that restricts viral replication and movement (Poulicard et al., 2024). Four primary alleles: L1, L2, L3, and L4 provide a stepwise, expanding spectrum of resistance (Tomita et al., 2011). The L1 allele offers protection against P0 pathotypes such as TMV, Tomato mosaic virus (ToMV), TMGMV and Bell pepper mottle virus (BPeMV). The L2 allele extends this resistance to include P1 pathotypes, including Paprika mild mottle virus (PaMMV), Obuda pepper virus (ObPV), TMV and TMGMV which can overcome L1-mediated resistance. L3 confers resistance against P0, P1, and P1,2 pathotypes, such as those of PMMoV capable of overcoming L2. The L4 allele further broadens this resistance to P1,2,3 pathotypes that can bypass L3-mediated resistance. Additionally, a temperature-sensitive allele, L1a, has been identified and may offer resistance under specific environmental conditions (Matsumoto et al., 2008)(Table 1). Despite these advances, the emergence of the P1,2,3,4 pathotype of PMMoV, capable of breaking L4 resistance which underscores the urgent need for novel resistance genes and breeding strategies to counter this rapidly evolving pathogen (Ojinaga et al., 2024). A recent study revealed that pepper plants carrying L resistance alleles (L1, L3, L4) initiate a HR response to Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) through recognition of its CP; however, this resistance was only partial, permitting transient systemic infection without the development of fruit symptoms (Eldan et al., 2022).

3.3 Recessive resistance genes

Recessive resistance genes arise from loss or alteration of critical host factors that viruses exploit for replication, translation, or movement. Such mutations prevent the virus from completing its infection cycle, offering a broader and more durable protection than dominant genes. They are particularly common against potyviruses, with many encoding eukaryotic translation initiation factors eIF4E or eIF4G, which are required for potyvirus RNA translation and replication complex formation. When these host factors are structurally altered or absent, the viral VPg protein fails to interact with them, thereby blocking viral RNA translation and replication. In Capsicum, pvr1 and pvr3 represent distinct loci conferring different resistance types to PepMoV (Murphy et al., 1998). For instance, pvr1 present in C. chinense PI159236 and PI152225, encodes an eIF4E homolog whose amino acid substitutions disrupt VPg–eIF4E binding, providing broad resistance to PepMoV, TEV, and PVY (Yoon et al., 2020). In contrast, pvr3 in C. annuum ‘Avelar’ restricts PepMoV differently; virus accumulates in inoculated leaves and vascular tissue but does not reach upper leaves. Co-infection with CMV disrupts this restriction (Guerini and Murphy, 1999).

Recessive genes pvr2 and pvr6, on chromosomes 4 and 3, confer digenic resistance to Pepper veinal mottle virus (PVMV), though their effect on PepMoV is unknown (Ruffel et al., 2006; Rubio et al., 2009) (Table 1). The pvr1 gene encodes an eIF4E homolog, and pvr6 likely encodes eIF(iso)4E; mutations in these factors confer potyvirus resistance (Wang and Krishnaswamy, 2012). Ectopic pvr1 expression in tomato imparts dominant resistance to PepMoV and TEV (Kang et al., 2007).

A novel recessive gene, cvr4, confers resistance to Chilli veinal mottle virus (ChiVMV), fine-mapped to a 2 Mb region on chromosome 11; functional validation identified DEM.v1.00021323 with resistance-associated alternative splicing (Lee et al., 2025). Similarly, cmr2, located on chromosome 8 in C. annuum ’Lam32’, confers broad resistance to CMV, including the virulent CMV-P1 strain, possibly by modulating host translation or replication pathways (Choi et al., 2018). Recently, bwvr, identified via bulked segregant RNA-seq, confers BBWV2 resistance and maps to a 116 kb region on chromosome 4 containing NPF1.2 (a nitrate transporter), which harbors a resistance-associated SNP that may alter virus–host transport dynamics (Kim et al., 2024a).

3.4 Avirulence genes

Viruses play a significant role in pathogenesis through both direct and indirect interactions. Plants possess R genes that provide defense against specific pathogens, leading to an incompatible interaction with viruses termed as avirulent pathogens. The pathogen molecule triggering this response is called the avirulence (Avr) determinant (Figure 2) (De Ronde et al., 2014). To identify these determinants, researchers often use reverse genetics, exchanging genome parts between viral DNA clones. Viral genes, including RNA polymerase subunits, movement proteins, and coat proteins, have been identified as avirulence factors. For example, the coat proteins of seven tobamoviruses infecting pepper such as TMV, TMGMV, PMMoV, ToMV BPeMV, ObPV, and PaMMV act as Avr factors, triggering resistance governed by their corresponding localization alleles (Tomita et al., 2011). The potyviral genome-linked protein (VPg) from potyviruses is a well-known avirulence factor associated with pvr1, pvr2 and pvr6 in C. annuum (Moury et al., 2004; Kang et al., 2005; Charron et al., 2008; Perez et al., 2012). VPg is a key protein in potyviruses that interacts with eIF4E and eIF(iso)4E. Mutations in these genes can disrupt this interaction, preventing viral replication (Ruffel et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2025).

Pepper harbors both dominant and recessive R genes against potyviruses. The dominant Pvr4 gene (from C. annuum ‘CM334’) confers extreme resistance to multiple potyviruses including PepMoV, PVY and PepSMV. The Avr determinant for Pvr4 is the viral RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase (NIb); single amino acid changes in NIb can abrogate Pvr4 recognition (Moury et al., 2023). Kim et al. (2015) demonstrated that the RdRp NIbs proteins of PepMoV, PVY and Pepper severe mosaic virus (PepSMV), function as Avr factors, triggering Pvr4-mediated resistance in pepper plants.

Pepper resistance to Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) is generally quantitative, but a major locus Cmr1 (on chromosome 2) confers broad resistance to most CMV strains (Kang et al., 2010). The Avr factor for Cmr1 has been mapped to the viral P1 helicase domain. The CMV‐P1 strain can overcome Cmr1, and Kang et al. (2012) showed that the RNA1‐encoded P1 helicase of CMV-P1 is necessary to infect Cmr1 plants (Kang et al., 2012). In other hosts, CMV coat protein or 2b protein are sometimes recognized (e.g. tomato’s Ty genes), but in pepper P1 appears to be the key effector. As with other viruses, strain specificity is common: Cmr1 confers resistance to some CMV isolates, while others (like CMV-P1) carry P1 variants that escape detection (Choi et al., 2016).

Pepper’s single dominant gene Tsw (from C. chinense PI159236) confers HR‐type resistance to TSWV (Kim et al., 2017). Recent work has identified the TSWV non‐structural RNA‐silencing suppressor protein NSs as the Avr elicitor for Tsw (De Ronde et al., 2013). Transient expression of NSs from a resistance‐inducing isolate triggers HR in Tsw‐carrying Capsicum, whereas NSs from a resistance‐breaking strain does not (De Ronde et al., 2013). This contrasts with tomato’s Sw-5b gene, which instead recognizes the TSWV movement protein NSm as its Avr effector (Huang et al., 2018). Thus, although pepper Tsw and tomato Sw-5b are orthologous NB‐LRRs conferring tospovirus resistance, they recognize different viral proteins, highlighting distinct resistance mechanisms and independent evolution.

3.5 Transcription factors

Transcription factors play a pivotal role in orchestrating antiviral defense in Capsicum spp., regulating hypersensitive response (HR) and defense gene expression through diverse mechanisms. While resistance (R) genes such as the L gene cluster directly recognize viral effectors to trigger HR, additional host factors, particularly transcription factors (TFs), play pivotal roles in amplifying and fine-tuning the immune response. These TFs mediate transcriptional reprogramming of defense-related genes, interact with signaling cascades such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, and modulate hypersensitive and systemic acquired resistance (SAR) responses. Early studies identified the basic region-leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor PPI1 in Capsicum chinense, which is specifically induced by PMMoV infection and restricts viral replication and spread, underscoring the importance of pathogen-responsive bZIP TFs in defense signaling (Lee et al., 2002). Subsequently, members of the NAC family were shown to contribute to virus resistance. CaNAC1, a nuclear-localized NAC TF, is induced during incompatible interactions with PMMoV, promoting HR cell death and activating downstream defense genes (Oh et al., 2005). Similarly, CaBtf3, a NAC subunit, regulates transcription of defense-associated genes during HR and maintains proper protein folding under viral stress, further supporting antiviral responses (Huh et al., 2012a).

WRKY transcription factors have also emerged as key regulators of pepper antiviral immunity. CaWRKYb binds W-box elements in the CaPR-10 promoter, positively regulating defense genes and enhancing resistance to TMV-P0; its knockdown reduces HR lesions and increases viral accumulation (Lim et al., 2011). CaWRKYd, a member of the WRKY IIa group, modulates TMV-mediated HR and PR gene expression, functioning as both a positive and negative regulator depending on context (Huh et al., 2012b). More recently, CaWRKYa was shown to be phosphorylated by TMV-responsive MAPKs (CaMK1 and CaMK2) and to enhance L-mediated resistance through transcriptional activation of PR genes, highlighting the integration of WRKY TFs with MAPK signaling pathways in virus defense (Huh et al., 2015).

4 Integrated genomic strategies for viral resistance in pepper

4.1 Genome based approach

In recent years, unprecedented advances in genomic resources and breeding technologies for pepper (Capsicum spp.) have accelerated the development of virus-resistant cultivars. Marker-assisted selection (MAS) has become a cornerstone of pepper breeding, particularly for traits governed by quantitative loci or recessive alleles and is complemented by advanced strategies such as marker-assisted backcrossing (MABC), recurrent selection (MARS), and pedigree selection (MAPS) to accelerate resistant cultivar development (Li et al., 2020a). Leveraging the extensive characterization of dominant and recessive resistance genes, along with their corresponding viral avirulence (Avr) genes, MAS has emerged as a highly effective tool for developing virus-resistant pepper cultivars. A wide array of molecular markers including SCAR, CAPS, KASP, SNP, and InDel markers has been developed for both dominant and recessive genes, such as the L gene cluster for PMMoV resistance, the Tsw gene for TSWV resistance, and the Pvr series for PepMoV resistance (Barka and Lee, 2020). Additional markers have been established for CMV (CaTm-int3HRM and InDel-2-134) (Kang et al., 2010; Guo et al., 2017) and Pepper yellow leaf curl virus (Chr-lcv-7 and Chr-lcv-12) (Siddique et al., 2022). These markers enable precise genotypic selection and integration of resistance loci into elite cultivars, supporting durable, broad-spectrum resistance.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are a powerful tool for dissecting the genetic architecture of plant virus resistance. By scanning the genomes of diverse plant lines, GWAS identifies DNA markers, primarily SNPs, associated with susceptibility or resistance, pinpointing candidate genes and loci for breeding. Beyond detecting individual resistance genes or QTLs, GWAS can reveal interactions between loci, providing a comprehensive view of resistance mechanisms. For instance, Tamisier et al. (2020) examined over 260 pepper accessions for PVY response and identified seven SNPs on chromosomes 4, 6, 9, and 12, including two closely linked to the pvr2 gene encoding eIF4E, while SNPs on chromosomes 6 and 12 overlapped with previously reported PVY resistance QTLs. Recently, Tamisier et al. (2022) conducted GWAS on 254 accessions for PVY response and identified a locus on chromosome 9 that controls systemic necrosis (tolerance) to PVY.

High‐quality reference genomes and pan‐genomes now capture the extensive structural variation in Capsicum; for instance, a graph‐based pan‐genome of 12 C. annuum accessions identified over 200,000 presence–absence variants (PAVs) and tens of thousands of copy‐number variants (Lee et al., 2022). Many of these PAVs co‐localize with loci associated with agronomic traits, including potyvirus resistance (Lee et al., 2022) offering a new reservoir of genetic diversity for breeding. The pepper pan‐genome has revealed many presence/absence variants in resistance gene analog clusters and other loci (Lee et al., 2022). For example, presence or absence of candidate NLR genes may underlie variations in potyvirus resistance among cultivars. By harnessing next-generation sequencing, Eun et al. (2016) applied genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) to uncover two novel major QTLs conferring resistance to CMV isolate P1 (CMV-P1). Dense SNP maps and genotyping platforms (Fluidigm, GBS) are now used to screen diverse collections: recent surveys of thousands of accessions identified C. chacoense and C. baccatum germplasm carrying novel potyvirus and TSWV resistance alleles (Ro et al., 2024). Integrating these genomic tools with traditional QTL mapping and MAS enables breeders to pyramid multiple resistance genes and track desirable haplotypes efficiently.

Genomic selection (GS) further accelerates breeding by using genome-wide markers to predict plant breeding values for complex traits, including disease resistance. Although genomic selection has been successfully implemented in major crops such as wheat, soybean, and rice, its application in chili pepper remains limited, except for fruit-related traits in Korean accessions that exhibited high prediction accuracies (Hong et al., 2020). By integrating genotypic and phenotypic data, GS is expected to enable the efficient selection of superior progenies without extensive phenotypic evaluation, thereby facilitating the development of multi-virus-resistant pepper cultivars, particularly for quantitatively inherited resistances controlled by multiple minor QTLs.

Collectively, these genome-based approaches provide actionable targets for developing pepper cultivars that combine durable viral resistance with agronomically and commercially desirable traits, such as yield, fruit quality, and stress tolerance. By integrating MAS, GWAS, pan-genomics, and genomic selection, breeding programs can more effectively produce multi-virus-resistant Capsicum cultivars suited to diverse agro-climatic and market conditions, underscoring the transformative potential of genomics in modern pepper breeding.

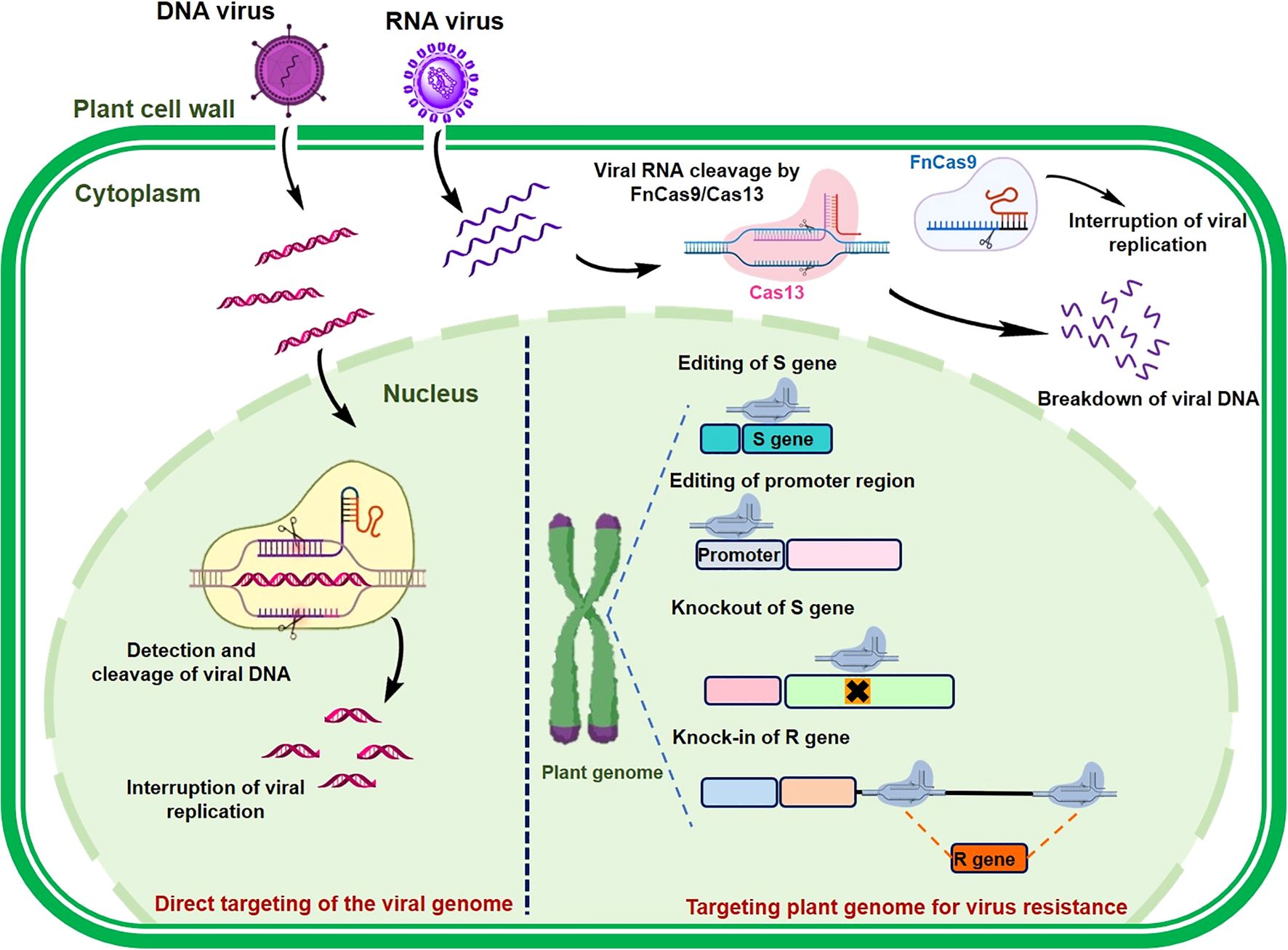

4.2 Genome editing approach

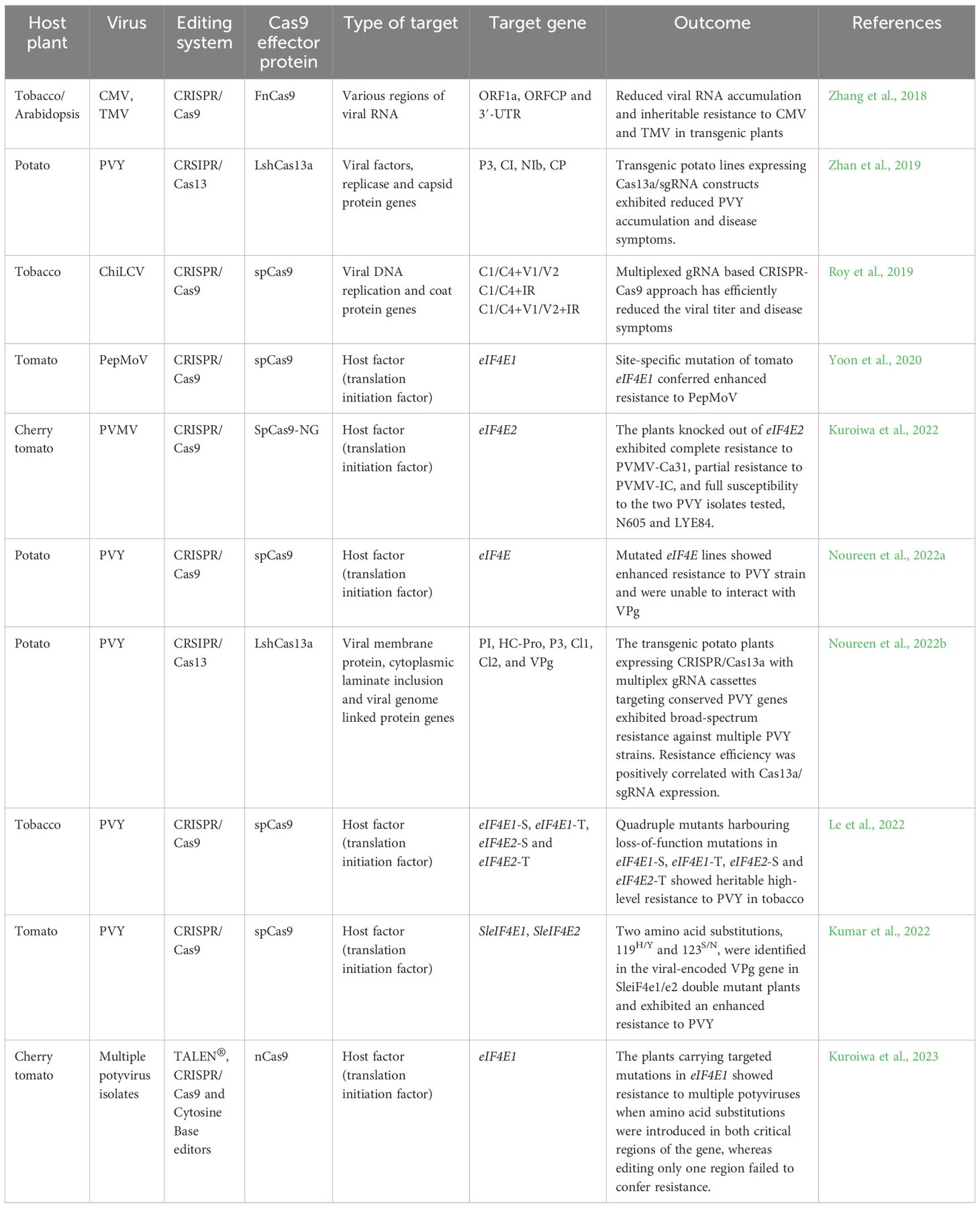

Recent breakthroughs in genome-editing technologies have provided powerful tools for precise modification of DNA sequences in plants. Among the genome-editing methods, CRISPR/Cas9 is distinguished by its remarkable efficiency, accuracy, and versatility, making it a preferred choice for plant genome editing and gene regulation (Jaganathan et al., 2018). CRISPR/Cas technology has been effectively employed to develop plant resistance to viral infections through various approaches, including plant-mediated resistance, alteration of host factors critical for viral entry, and direct manipulation of viral genomes (Figure 3). In plant-mediated resistance, the CRISPR/Cas system modifies host factors essential for viral infection, rather than directly targeting viral DNA or RNA. This is accomplished by disrupting host susceptibility genes (S-genes), which play a role in viral infection. In contrast, virus-mediated resistance focuses on editing the viral genome itself, with CRISPR/Cas systems precisely targeting and cleaving viral genetic material. CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing can directly modify S-genes to develop virus-resistant crops. Although research on genome editing for virus resistance in peppers is currently lacking, this strategy has been successfully applied in other crop varieties, conferring resistance to a broad range of viruses, including those that infect peppers. As outlined in Table 2, genome-editing strategies targeting both viral and host factor genes in other crops provide valuable insights to guide future efforts in developing virus-resistant pepper cultivars.

Figure 3. Class II CRISPR/Cas Systems for targeting viral and host genomes to engineer viral resistance in plants. When DNA viruses invade plant cells, the sgRNA-Cas9 complex recognizes and cleaves or alters the viral double-stranded DNA. For RNA viruses, both FnCas9 and Cas13a proteins, guided by their specific sgRNA or crRNA, effectively target and cut the viral genome. Additionally, CRISPR/Cas9 can modify host susceptibility factors, hindering viral infection by directly editing or knocking out plant susceptibility (S) genes, modifying promoter sequences to block pathogen-effector interactions, or facilitating the insertion of plant resistance (R) genes through homology-directed repair (HDR).

Table 2. Application of genome editing techniques to confer resistance against pepper-infecting viruses in other crops.

Despite the availability of whole-genome sequences and genome-editing tools for peppers, the precision gene editing of peppers remains in its infancy, primarily due to the absence of a reliable transformation method. Although the limited morphogenic response of pepper explants is often seen as a key obstacle, other factors such as efficient DNA transfer and integration, along with the selection of recipient cells capable of regeneration, are also critical for successfully producing transgenic plants. Li et al. (2020b) were the first to pinpoint genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 editing sites in pepper using the ‘Zunla-1’ reference genome. They further evaluated the specificity of these editing sites through a whole-genome alignment analyses. This study provided an essential groundwork for advancing CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in pepper. Concurrently, Kim et al. (2020) developed a stable DNA-free screening system for gene editing in hot pepper (‘CM334’) and sweet pepper (‘Dempsey’) by targeting the CaMLO2 gene, linked to powdery mildew susceptibility, using CRISPR/Cas9 and Cpf1 (LbCpf1) systems. They demonstrated effective gene editing through PEG-mediated delivery of RNP complexes into protoplasts, establishing ‘Dempsey’ leaf protoplasts as a reliable platform for validating CRISPR tools and enhancing disease resistance in pepper plants. Subsequently, they developed a stable Agrobacterium-mediated gene editing method using the CRISPR/Cas9 system in the same pepper cultivars, using callus cultures to target the CaMLO2 gene (Park et al., 2021). Recently, a biolistic method for delivering CRISPR/Cas9 reagents into peppers has been established, utilizing a construct containing two distinct guide RNAs that target the phytoene desaturase (CaPDS) gene (Bulle et al., 2024). Currently, virus-induced gene editing (VIGE) system leverages viral vectors to deliver gene-editing tools, such as CRISPR/Cas9, directly into plant cells (Daròs et al., 2023). This method utilizes the natural ability of viruses to infect plants, allowing for efficient and targeted editing of genes. More recently, two VIGE strategies have been developed using Tobacco rattle virus (TRV) and PVX vectors to target the CaPDS gene in Solanaceous crops, including tomato, potato, and eggplant (Lee et al., 2024), Liu et al (2023) established a transient CRISPR/Cas delivery system utilizing engineered TSWV vectors, which facilitates efficient somatic gene editing across various crop species, including pepper. Subsequently, they expanded their research to successfully generate transgene-free pepper plants, achieving high somatic editing frequencies of 57.65% and 75.73% at the CaPDS-3 and CaPDS-4 target sites, respectively, using TSWV vectors (Zhao et al., 2024). Thus, continued advancements in genome editing technologies, coupled with established transient and stable transformation methods will facilitate the successful development of virus-resistant pepper varieties in the future.

5 Discussion and future directions

Moving forward, enhancing viral resistance in Capsicum spp. will require the strategic integration of conventional breeding approaches with cutting-edge genomic and biotechnological innovations. Recent progress in next-generation sequencing (NGS), genome-wide association studies (GWAS), and high-throughput SNP genotyping have facilitated the identification and fine mapping of resistance genes or QTLs, enabling the development of reliable markers for marker-assisted selection (MAS) and genomic selection (GS). Tools such as R gene enrichment sequencing (RenSeq) have revolutionized high-throughput screening of germplasm and mutants, allowing for the rapid identification of candidate R genes recognizing key effectors (Jupe et al., 2014). To enhance the durability and broaden the resistance spectrum, strategies such as stacking multiple R genes are being explored. Furthermore, the development of RNA interference (RNAi)-based biopesticides is emerging as a targeted strategy to manage plant viruses, with the potential for effective application through suitable delivery mechanisms. The CRISPR-Cas system, a powerful genome-editing tool, presents additional advantages over RNAi approaches, particularly with the recent discovery of RNA-targeting CRISPR-associated proteins. However, the application of CRISPR-Cas system for engineering virus resistance in Capsicum is still in its early stages, constrained by transformation efficiency and the need for optimized delivery systems.

Interestingly, several resistance loci and resistance gene clusters identified in Capsicum are located near or within to QTL regions controlling fruit morphology traits such as fruit size and shape. For instance, the genomic region of the Pvr4 gene on chromosome 10 is positioned adjacent to the fruit shape locus–associated QTL fs10 (Borovsky et al., 2022) suggesting a potential co-evolution or genetic linkage between viral resistance and fruit development pathways. Moreover, transcription factors such as CaWRKY, which play roles in antiviral defense, have also been implicated in the regulation of fruit ripening and fruit maturation in pepper (Huh et al., 2012b; Cheng et al., 2016). These studies highlight the interconnected between defense and developmental networks in Capsicum. Integrating such loci into breeding pipelines through marker-assisted selection (MAS) and genomic selection (GS) will facilitate the development of high-yielding, virus-resistant cultivars with desirable fruit characteristics, thereby bridging molecular insights with practical advances in pepper improvement.

Future research should focus on validating the genomic regions and candidate genes identified through GWAS, pan-genome, and transcriptomic analyses in diverse genetic backgrounds. Functional validation using gene editing, mutant screening, and transcriptomic profiling under viral challenge will be essential to confirm their roles in conferring resistance. Additionally, the translation of these genomic discoveries into field-ready breeding programs through marker-assisted backcrossing, genomic selection, and genome-edited lines will bridge the gap between laboratory findings and practical cultivar development. Collaborative and multi-disciplinary breeding initiatives that integrate genomic insights, molecular validation, and market-oriented trait selection will not only enhance the durability of resistance but also accelerate the adoption of virus-resistant cultivars with improved consumer and commercial acceptance. Ultimately, the seamless integration of genomic innovation with traditional breeding will enable the development of resilient Capsicum varieties, fortifying global pepper production against future viral threats.

Author contributions

JS: Writing – original draft. W-HK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean Government (RS-2024-00338092), and by the research grant for the new professor of the Gyeongsang National University in 2024 (GNU-2024-220084).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akhter, M. S., Nakahara, K. S., and Masuta, C. (2021). Resistance induction based on the understanding of molecular interactions between plant viruses and host plants. Virol. J. 18, 176. doi: 10.1186/s12985-021-01647-4

Barka, G. D. and Lee, J. (2020). Molecular marker development and gene cloning for diverse disease resistance in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.): current status and prospects. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 8, 89–113. doi: 10.9787/PBB.2020.8.2.89

Borovsky, Y., Raz, A., Doron-Faigenboim, A., Zemach, H., Karavani, E., and Paran, I. (2022). Pepper fruit elongation is controlled by Capsicum annuum ovate family protein 20. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 815589. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.815589

Bulle, M., Venkatapuram, A. K., Abbagani, S., and Kirti, P. B. (2024). CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing of Phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene in chilli pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 22, 100380. doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2024.100380

Bwalya, J. and Kim, K.-H. (2023). The crucial role of chloroplast-related proteins in viral genome replication and host defense against positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses. Plant Pathol. J. 39, 28. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.RW.10.2022.0139

Caranta, C., Palloix, A., Gebre-Selassie, K., Lefebvre, V., Moury, B., and Daubeze, A. M. (1996). A complementation of two genes originating from susceptible Capsicum annuum lines confers a new and complete resistance to pepper veinal mottle virus. Phytopathology 86, 739–743. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-86-739

Caranta, C., Palloix, A., Lefebvre, V., and Daubeze, A. M. (1997). QTLs for a component of partial resistance to cucumber mosaic virus in pepper: restriction of virus installation in host-cells. Theor. Appl. Genet. 94, 431–438. doi: 10.1007/s001220050433

Carrington, J. C., Kasschau, K. D., Mahajan, S. K., and Schaad, M. C. (1996). Cell-to-cell and long-distance transport of viruses in plants. Plant Cell 8, 1669. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1669

Chaim, A., Grube, R. C., Lapidot, M., Jahn, M., and Paran, I. (2001). Identification of quantitative trait loci associated with resistance to cucumber mosaic virus in Capsicum annuum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 102, 1213–1220. doi: 10.1007/s001220100581

Charron, C., Nicolaï, M., Gallois, J., Robaglia, C., Moury, B., Palloix, A., et al. (2008). Natural variation and functional analyses provide evidence for co-evolution between plant eIF4E and potyviral VPg. Plant J. 54, 56–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03407.x

Cheng, Y., JalalAhammed, G., Yu, J., Yao, Z., Ruan, M., Ye, Q., et al. (2016). Putative WRKYs associated with regulation of fruit ripening revealed by detailed expression analysis of the WRKY gene family in pepper. Sci. Rep. 6, 39000. doi: 10.1038/srep39000

Choi, S., Lee, J.-H., Kang, W.-H., Kim, J., Huy, H.-N., Park, S.-W., et al. (2018). Identification of cucumber mosaic resistance 2 (cmr2) that confers resistance to a new cucumber mosaic virus isolate P1 (CMV-P1) in pepper (Capsicum spp.). Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1106. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01106

Choi, Y., Kang, M.-Y., Lee, J.-H., Kang, W.-H., Hwang, J., Kwon, J.-K., et al. (2016). Isolation and characterization of pepper genes interacting with the CMV-P1 helicase domain. PloS One 11, e0146320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146320

Collier, S. M. and Moffett, P. (2009). NB-LRRs work a “bait and switch” on pathogens. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.08.001

Daròs, J.-A., Pasin, F., and Merwaiss, F. (2023). CRISPR-Cas-based plant genome engineering goes viral. Mol. Plant 16, 660–661. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2023.03.010

De Ronde, D., Butterbach, P., and Kormelink, R. (2014). Dominant resistance against plant viruses. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 307. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00307

De Ronde, D., Butterbach, P., Lohuis, D., Hedil, M., Van Lent, J. W. M., and Kormelink, R. (2013). Tsw gene-based resistance is triggered by a functional RNA silencing suppressor protein of the Tomato spotted wilt virus. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 405–415. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12016

Eldan, O., Ofir, A., Luria, N., Klap, C., Lachman, O., Bakelman, E., et al. (2022). Pepper plants harboring l resistance alleles showed tolerance toward manifestations of tomato brown rugose fruit virus disease. Plants 11, 2378. doi: 10.3390/plants11182378

Eun, M. H., Han, J.-H., Yoon, J. B., and Lee, J. (2016). QTL mapping of resistance to the Cucumber mosaic virus P1 strain in pepper using a genotyping-by-sequencing analysis. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 57, 589–597. doi: 10.1007/s13580-016-0128-3

Fang, M., Yu, J., Kwak, H.-R., and Kim, K.-H. (2022). Identification of viral genes involved in pepper mottle virus replication and symptom development in Nicotiana benthamiana. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1048074. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1048074

FAOSTAT. (2024). FAO online statistical database (Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)). Available online at: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/.

Genda, Y., Kanda, A., Hamada, H., Sato, K., Ohnishi, J., and Tsuda, S. (2007). Two amino acid substitutions in the coat protein of Pepper mild mottle virus are responsible for overcoming the L4 gene-mediated resistance in Capsicum spp. Phytopathology 97, 787–793. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-97-7-0787

Grube, R.-C., Zhang, Y., Murphy, J.-F., Loaiza-Figueroa, F., Lackney, V.-K., Provvidenti, R., et al. (2000). New source of resistance to Cucumber mosaic virus in Capsicum frutescens. Plant Dis. 84, 885–891. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.8.885

Guerini, M. N. and Murphy, J. F. (1999). Resistance of Capsicum annuum ‘Avelar’ to pepper mottle potyvirus and alleviation of this resistance by co-infection with cucumber mosaic cucumovirus are associated with virus movement. J. Gen. Virol. 80, 2785–2792. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-10-2785

Guo, G., Wang, S., Liu, J., Pan, B., Diao, W., Ge, W., et al. (2017). Rapid identification of QTLs underlying resistance to Cucumber mosaic virus in pepper (Capsicum frutescens). Theor. Appl. Genet. 130, 41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00122-016-2790-3

Han, K., Zheng, H., Ji, M., Cui, W., Hu, S., Peng, J., et al (2020). A single amino acid in coat protein of Pepper mild mottle virus determines its subcellular localization and the chlorosis symptom on leaves of pepper. J. Gen. Virol. 101, 565–570. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001398

Hernández-Pérez, T., Gómez-García, M., Del, R., Valverde, M. E., and Paredes-López, O. (2020). Capsicum annuum (hot pepper): An ancient Latin-American crop with outstanding bioactive compounds and nutraceutical potential. A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 19, 2972–2993. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12634

Hong, J.-P., Ro, N., Lee, H.-Y., Kim, G. W., Kwon, J.-K., Yamamoto, E., et al. (2020). Genomic selection for prediction of fruit-related traits in pepper (Capsicum spp.). Front. Plant Sci. 11, 570871. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.570871

Huang, C., Liu, Y., Yu, H., Yuan, C., Zeng, J., Zhao, L., et al. (2018). Non-structural protein NSm of Tomato spotted wilt virus is an avirulence factor recognized by resistance genes of tobacco and tomato via different elicitor active sites. Viruses 10, 660. doi: 10.3390/v10110660

Huh, S. U., Kim, K.-J., and Paek, K.-H. (2012a). Capsicum annuum basic transcription factor 3 (CaBtf3) regulates transcription of pathogenesis-related genes during hypersensitive response upon Tobacco mosaic virus infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 417, 910–917. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.074

Huh, S. U., Lee, G.-J., Jung, J. H., Kim, Y., Kim, Y. J., and Paek, K.-H. (2015). Capsicum annuum transcription factor WRKYa positively regulates defense response upon TMV infection and is a substrate of CaMK1 and CaMK2. Sci. Rep. 5, 7981. doi: 10.1038/srep07981

Huh, S. U., Lee, G.-J., Kim, Y. J., and Paek, K.-H. (2012b). Capsicum annuum WRKY transcription factor d (CaWRKYd) regulates hypersensitive response and defense response upon Tobacco mosaic virus infection. Plant Sci. 197, 50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.08.013

Ibiza, V. P., Cañizares, J., and Nuez, F. (2010). EcoTILLING in Capsicum species: searching for new virus resistances. BMC Genomics 11, 631. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-631

Jaganathan, D., Ramasamy, K., Sellamuthu, G., Jayabalan, S., and Venkataraman, G. (2018). CRISPR for crop improvement: an update review. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 985. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00985

Janzac, B., Fabre, M., Palloix, A., and Moury, B. (2009). Phenotype and spectrum of action of the Pvr4 resistance in pepper against potyviruses, and selection for virulent variants. Plant Pathol. 58, 443–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2008.01992.x

Jones, R. A. C. (2021). Global plant virus disease pandemics and epidemics. Plants 10, 233. doi: 10.3390/plants10020233

Jones, J. D. G. and Dangl, J. L. (2006). The plant immune system. Nature 444, 323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286

Jovanović, I., Frantová, N., and Zouhar, J. (2023). A sword or a buffet: plant endomembrane system in viral infections. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1226498. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1226498

Jupe, F., Chen, X., Verweij, W., Witek, K., Jones, J. D. G., and Hein, I. (2014). Genomic DNA library preparation for resistance gene enrichment and sequencing (RenSeq) in plants. Plant-Pathogen Interact. Methods Protoc. 1127, 291–303. doi: 10.1007/978‑1‑62703‑986‑4_22

Kang, W.-H., Hoang, N.-H., Yang, H.-B., Kwon, J.-K., Jo, S.-H., Seo, J.-K., et al. (2010). Molecular mapping and characterization of a single dominant gene controlling CMV resistance in peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 120, 1587–1596. doi: 10.1007/s00122-010-1278-9

Kang, W.-H., Lee, J., Koo, N., Kwon, J.-S., Park, B., Kim, Y.-M., et al (2022). Universal gene co-expression network reveals receptor-like protein genes involved in broad-spectrum resistance in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Hortic. Res. 9, uhab003. doi: 10.1093/hr/uhab003

Kang, W.-H., Seo, J.-K., Chung, B. N., Kim, K.-H., and Kang, B.-C. (2012). Helicase domain encoded by Cucumber mosaic virus RNA1 determines systemic infection of Cmr1 in pepper. PloS One 7, e43136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043136

Kang, W.-H., Sim, Y.-M., Koo, N., Nam, J.-Y., Lee, J., Kim, N., et al (2020). Transcriptome profiling of abiotic responses to heat, cold, salt, and osmotic stress of Capsicum annuum L. Sci. Data 7, 17. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-0352-7

Kang, B.-C., Yeam, I., and Jahn, M. M. (2005). Genetics of plant virus resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43, 581–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.011205.141140

Kang, B., Yeam, I., Li, H., Perez, K. W., and Jahn, M. M. (2007). Ectopic expression of a recessive resistance gene generates dominant potyvirus resistance in plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 5, 526–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00262.x

Kenyon, L., Kumar, S., Tsai, W.-S., and Hughes, J. D. (2014). “Virus diseases of peppers (Capsicum spp.) and their control,” in Advances in virus research. Eds. Loebenstein, G. and Katis, N. I. (Waltham, Massachusetts: Elsevier), 297–354.

Kim, M.-K., Kwak, H.-R., Han, J.-H., Ko, S.-J., Lee, S.-H., Park, J.-W., et al (2008). Isolation and characterization of Pepper mottle virus infecting tomato in Korea. Plant Pathol. J. 24, 152–158. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.2008.24.2.152

Kim, H., Choi, J., and Won, K.-H. (2020). A stable DNA-free screening system for CRISPR/RNPs-mediated gene editing in hot and sweet cultivars of Capsicum annuum. BMC Plant Biol. 20, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02665-0

Kim, S.-B., Kang, W.-H., Huy, H.-N., Yeom, S.-I., An, J.-T., Kim, S., et al. (2017). Divergent evolution of multiple virus-resistance genes from a progenitor in Capsicum spp. New Phytol. 213, 886–899. doi: 10.1111/nph.14177

Kim, Y.-J., Jonson, M. G., Choi, H. S., Ko, S.-J., and Kim, K.-H. (2009). Molecular characterization of Korean Pepper mottle virus isolates and its relationship to symptom variations. Virus Res. 144, 83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.04.003

Kim, J.-M., Lee, J.-H., Park, S.-R., Kwon, J.-K., Ro, N.-Y., and Kang, B.-C. (2024a). Molecular mapping of the broad bean wilt virus 2 resistance locus bwvr in Capsicum annuum using BSR-seq. Theor. Appl. Genet. 137, 97. doi: 10.1007/s00122-024-04603-2

Kim, S.-B., Lee, H.-Y., Seo, S., Lee, J. H., and Choi, D. (2015). RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (NIb) of the potyviruses is an avirulence factor for the broad-spectrum resistance gene Pvr4 in Capsicum annuum cv. CM334. PloS One 10, e0119639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119639

Kim, N., Lee, J., Yeom, S.-I., Kang, N.-J., and Kang, W.-H. (2024b). The landscape of abiotic and biotic stress-responsive splice variants with deep RNA-seq datasets in hot pepper. Sci. Data 11, 381. doi: 10.1038/s41597-024-03239-7

Kim, W.-R., Thiruvengadam, M., and Kim, S.-H. (2025). Metabolomic study of marketable and unmarketable chili peppers (Capsicum annuum L.) classified by the fruit size and shape. Food Chem. 480, 143897. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.143897

Kumar, S., Abebie, B., Kumari, R., Kravchik, M., Shnaider, Y., Leibman, D., et al. (2022). Development of PVY resistance in tomato by knockout of host eukaryotic initiation factors by CRISPR-Cas9. Phytoparasitica 50, 743–756. doi: 10.1007/s12600-022-00991-7

Kuroiwa, K., Danilo, B., Perrot, L., Thenault, C., Veillet, F., Delacote, F., et al. (2023). An iterative gene editing strategy broadens eIF4E1 genetic diversity in Solanum lycopersicum and generates resistance to multiple potyvirus isolates. Plant Biotechnol. J. 21, 918–930. doi: 10.1111/pbi.14003

Kuroiwa, K., Thenault, C., Nogué, F., Perrot, L., Mazier, M., and Gallois, J.-L. (2022). CRISPR-based knock-out of eIF4E2 in a cherry tomato background successfully recapitulates resistance to pepper veinal mottle virus. Plant Sci. 316, 111160. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2021.111160

Kwon, J.-S., Lee, J., Shilpha, J., Jang, H., and Kang, W.-H. (2024b). The landscape of sequence variations between resistant and susceptible hot peppers to predict functional candidate genes against bacterial wilt disease. BMC Plant Biol. 24, 1036. doi: 10.1186/s12870-024-05742-w

Kwon, J.-S., Nam, J.-Y., Yeom, S.-I., and Kang, W.-H. (2021). Leaf-to-whole plant spread bioassay for pepper and Ralstonia solanacearum interaction determines inheritance of resistance to bacterial wilt for further breeding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 2279. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052279

Kwon, J.-S., Shilpha, J., Lee, J., and Yeom, S.-I. (2024a). Beyond NGS data sharing for plant ecological resilience and improvement of agronomic traits. Sci. Data 11, 466. doi: 10.1038/s41597-024-03305-0

Lapidot, M., Paran, I., Ben-Joseph, R., Ben-Harush, S., Pilowsky, M., Cohen, S., et al. (1997). Tolerance to cucumber mosaic virus in pepper: development of advanced breeding lines and evaluation of virus level. Plant Dis. 81, 185–188. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1997.81.2.185

Le, N. T., Tran, H. T., Bui, T. P., Nguyen, G. T., Van Nguyen, D., Ta, D. T., et al. (2022). Simultaneously induced mutations in eIF4E genes by CRISPR/Cas9 enhance PVY resistance in tobacco. Sci. Rep. 12, 14627. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-18923-0

Lee, J.-H., Venkatesh, J., Jo, J., Jang, S., Kim, G.-W., Kim, J.-M., et al. (2022). High-quality chromosome-scale genomes facilitate effective identification of large structural variations in hot and sweet peppers. Hortic. Res. 9, uhac210. doi: 10.1093/hr/uhac210

Lee, S.-Y., Kang, B., Venkatesh, J., Lee, J.-H., Lee, S., Kim, J.-M., et al. (2024). Development of virus-induced genome editing methods in Solanaceous crops. Hortic. Res. 11, uhad233. doi: 10.1093/hr/uhad233

Lee, J.-H., Kim, J.-M., Kwon, J.-K., and Kang, B.-C. (2025). Fine mapping of the Chilli veinal mottle virus resistance 4 (cvr4) gene in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 138, 19. doi: 10.1007/s00122-024-04805-8

Lee, S. J., Lee, M. Y., Yi, S. Y., Oh, S. K., Choi, S. H., Her, N. H., et al. (2002). PPI1: a novel pathogen-induced basic region-leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor from pepper. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 15, 540–548. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.6.540

Lee, J. and Yeom, S.-I. (2023). Global co-expression network for key factor selection on environmental stress RNA-seq dataset in Capsicum annuum. Sci. Data 10, 692. doi: 10.1038/s41597-023-02592-3

Li, G., Zhou, Z., Liang, L., Song, Z., Hu, Y., Cui, J., et al. (2020b). Genome-wide identification and analysis of highly specific CRISPR/Cas9 editing sites in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). PloS One 15, e0244515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244515

Li, N., Yu, C., Yin, Y., Gao, S., Wang, F., Jiao, C., et al. (2020a). Pepper crop improvement against cucumber mosaic virus (CMV): A review. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 598798. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.598798

Lim, J. H., Park, C.-J., Huh, S. U., Choi, L. M., Lee, G. J., Kim, Y. J., et al. (2011). Capsicum annuum WRKYb transcription factor that binds to the CaPR-10 promoter functions as a positive regulator in innate immunity pon TMV infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 411, 613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.002

Liu, Y., Wang, S., Zhao, D., Zhao, C., Yu, H., Zeng, J., et al. (2025). Simultaneous knockout of multiple eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E genes confers durable and broad-spectrum resistance to potyviruses in tobacco. aBIOTECH 6, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s42994-025-00216-5

Liu, Q., Zhao, C., Sun, K., Deng, Y., and Li, Z. (2023). Engineered biocontainable RNA virus vectors for non-transgenic genome editing across crop species and genotypes. Mol. Plant 16, 616–631. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2023.02.003

Lozano-Durán, R. (2024). Viral recognition and evasion in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 75, 655–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-060223-030224

Matsumoto, K., Sawada, H., Matsumoto, K., Hamada, H., Yoshimoto, E., Ito, T., et al. (2008). The coat protein gene of tobamovirus P 0 pathotype is a determinant for activation of temperature-insensitive L 1a-gene-mediated resistance in Capsicum plants. Arch. Virol. 153, 645–650. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0032-y

Medina-Puche, L. and Lozano-Durán, R. (2019). Tailoring the cell: a glimpse of how plant viruses manipulate their hosts. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 52, 164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2019.09.007

Mihailova, B., Stoimenova, E., Petrov, P., and Stoynova-Bakalova, E. (2013). Movement of cucumber mosaic virus in resistant pepper lines. Comp. Rendus l’Acadeìmie Bulg. Sci. 66, 911–918. doi: 10.7546/CR-2013-66-6-13101331-19

Moury, B., Morel, C., Johansen, E., Guilbaud, L., Souche, S., Ayme, V., et al. (2004). Mutations in Potato virus Y genome-linked protein determine virulence toward recessive resistances in Capsicum annuum and Lycopersicon hirsutum. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 17, 322–329. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.3.322

Moury, B., Michon, T., Simon, V., and Palloix, A. (2023). A Single Nonsynonymous Substitution in the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase of Potato virus Y Allows the Simultaneous Breakdown of Two Different Forms of Antiviral Resistance in Capsicum annuum. Viruses 15, 1081. doi: 10.3390/v15051081

Moury, B. and Verdin, E. (2012). “Viruses of pepper crops in the Mediterranean basin: a remarkable stasis,” in Advances in virus research. Eds. Mahy, B. W. J. and Van Regenmortel, M. H. V. (San Diego, California: Elsevier), 127–162.

Murphy, J. F., Blauth, J. R., Livingstone, K. D., Lackney, V. K., and Jahn, M. K. (1998). Genetic mapping of the pvr1 locus in Capsicum spp. and evidence that distinct potyvirus resistance loci control responses that differ at the whole plant and cellular levels. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11, 943–951. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.10.943

Nguyen-Dinh, V. and Herker, E. (2021). Ultrastructural features of membranous replication organelles induced by positive-stranded RNA viruses. Cells 10, 2407. doi: 10.3390/cells10092407

Nono-Womdim, R., Gebre-Selassie, K., Palloix, A., Pochard, E., and Marchoux, G. (1993). Study of multiplication of cucumber mosaic virus in susceptible and resistant Capsicum annuum lines. Ann. Appl. Biol. 122, 49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1744‑7348.1993.tb04013.x

Noureen, A., Khan, M. Z., Amin, I., Zainab, T., and Mansoor, S. (2022a). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeting of susceptibility factor eIF4E-enhanced resistance against potato virus Y. Front. Genet. 13, 922019. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.922019

Noureen, A., Zuhaib Khan, M., Amin, I., Zainab, T., Ahmad, N., Haider, S., et al. (2022b). Broad-spectrum resistance against multiple PVY-strains by CRSIPR/Cas13 system in Solanum tuberosum crop. GM Crops Food 13, 7–111. doi: 10.1080/21645698.2022.2080481

Oh, S.-K., Lee, S., Yu, S. H., and Choi, D. (2005). Expression of a novel NAC domain-containing transcription factor (CaNAC1) is preferentially associated with incompatible interactions between chili pepper and pathogens. Planta 222, 876–887. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0030-1

Ojinaga, M., Aragones, A., Hernández, M., and Larregla, S. (2024). Phenotypical and molecular characterization of new pepper genotypes resistant to Chili pepper mild mottle virus firstly detected in Europe and other tobamoviruses. Sci. Hortic. 330, 113074. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113074

Park, S., Kim, H.-B., Jeon, H.-J., and Kim, H. (2021). Agrobacterium-mediated Capsicum annuum gene editing in two cultivars, hot pepper CM334 and bell pepper Dempsey. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 3921. doi: 10.3390/ijms22083921

Perez, K., Yeam, I., Kang, B.-C., Ripoll, D. R., Kim, J., Murphy, J. F., et al. (2012). Tobacco etch virus infectivity in Capsicum spp. is determined by a maximum of three amino acids in the viral virulence determinant VPg. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 25, 1562–1573. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-04-12-0091-R

Pernezny, K., Roberts, P. D., Murphy, J. F., and Goldberg, N. P. (2003). Compendium of pepper diseases (St. Paul, MN: APS Press).

Piau, M. and Schmitt-Keichinger, C. (2023). The hypersensitive response to plant viruses. Viruses 15, 2000. doi: 10.3390/v15102000

Poulicard, N., Pagán, I., González-Jara, P., Mora, M. Á., Hily, J. M., Fraile, A., et al. (2024). Repeated loss of the ability of a wild pepper disease resistance gene to function at high temperatures suggests that thermos resistance is a costly trait. New Phytol. 241, 845–860. doi: 10.1111/nph.19371

Rai, A., Sivalingam, P. N., and Senthil-Kumar, M. (2022). A spotlight on non-host resistance to plant viruses. PeerJ 10, e12996. doi: 10.7717/peerj.12996

Ro, N., Lee, G.-A., Ko, H.-C., Oh, H., Lee, S., Haile, M., et al. (2024). Exploring disease resistance in pepper (Capsicum spp.) germplasm collection using Fluidigm SNP genotyping. Plants 13, 1344. doi: 10.3390/plants13101344

Roy, A., Zhai, Y., Ortiz, J., Neff, M., Mandal, B., Mukherjee, S. K., et al. (2019). Multiplexed editing of a begomovirus genome restricts escape mutant formation and disease development. PloS One 14, e0223765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223765

Rubio, M., Nicolaï, M., Caranta, C., and Palloix, A. (2009). Allele mining in the pepper gene pool provided new complementation effects between pvr2-eIF4E and pvr6-eIF (iso) 4E alleles for resistance to pepper veinal mottle virus. J. Gen. Virol. 90, 2808–2814. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.013151-0

Ruffel, S., Dussault, M.-H., Palloix, A., Moury, B., Bendahmane, A., Robaglia, C., et al. (2002). A natural recessive resistance gene against potato virus Y in pepper corresponds to the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E). Plant J. 32, 1067–1075. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01499.x

Ruffel, S., Gallois, J.-L., Moury, B., Robaglia, C., Palloix, A., and Caranta, C. (2006). Simultaneous mutations in translation initiation factors eIF4E and eIF (iso) 4E are required to prevent pepper veinal mottle virus infection of pepper. J. Gen. Virol. 87, 2089–2098. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81817-0

Scholthof, K. G., Adkins, S., Czosnek, H., Palukaitis, P., Jacquot, E., Hohn, T., et al. (2011). Top 10 plant viruses in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 938–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00752.x

Sharma, V., Devendran, R., Kumar, M., Prajapati, R., Kumar, R., and Prakash, V. (2025). Molecular dynamics of plant-virus interactions: unravelling the dual role of the ubiquitin proteasome system. Stress Biol. 5, 12. doi: 10.1007/s44154-024-00210-9

Shilpha, J., Lee, J., Kwon, J.-S., Lee, H.-A., Nam, J.-Y., Jang, H., et al. (2024). An improved bacterial mRNA enrichment strategy in dual RNA sequencing to unveil the dynamics of plant-bacterial interactions. Plant Methods 20, 99. doi: 10.1186/s13007-024-01227-x

Siddique, M. I., Lee, J.-H., Ahn, J.-H., Kusumawardhani, M. K., Safitri, R., Harpenas, A., et al. (2022). Genotyping-by-sequencing-based QTL mapping reveals novel loci for Pepper yellow leaf curl virus (PepYLCV) resistance in Capsicum annuum. PloS One 17, e0264026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264026

Tamisier, L., Szadkowski, M., Girardot, G., Djian-Caporalino, C., Palloix, A., Hirsch, J., et al. (2022). Concurrent evolution of resistance and tolerance to potato virus Y in Capsicum annuum revealed by genome-wide association. Mol. Plant Pathol. 23, 254–264. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13157

Tamisier, L., Szadkowski, M., Nemouchi, G., Lefebvre, V., Szadkowski, E., Duboscq, R., et al. (2020). Genome-wide association mapping of QTLs implied in potato virus Y population sizes in pepper: evidence for widespread resistance QTL pyramiding. Mol. Plant Pathol. 21, 3–16. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12874

Tian, L., Hossbach, B. M., and Feussner, I. (2024). Small size, big impact: Small molecules in plant systemic immune signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 81, 102618. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2024.102618

Tomita, R., Sekine, K.-T., Mizumoto, H., Sakamoto, M., Murai, J., Kiba, A., et al. (2011). Genetic basis for the hierarchical interaction between Tobamovirus spp. and L resistance gene alleles from different pepper species. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 24, 108–117. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-10-0127

Tran, P.-T., Choi, H., Choi, D., and Kim, K.-H. (2015). Molecular characterization of Pvr9 that confers a hypersensitive response to Pepper mottle virus (a potyvirus) in Nicotiana benthamiana. Virology 481, 113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.052

Tran, P.-T., Choi, H., Kim, S.-B., Lee, H.-A., Choi, D., and Kim, K.-H. (2014). A simple method for screening of plant NBS-LRR genes that confer a hypersensitive response to plant viruses and its application for screening candidate pepper genes against Pepper mottle virus. J. Virol. Methods 201, 57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.02.003

Venkatesh, J., An, J., Kang, W.-H., Jahn, M., and Kang, B.-C. (2018). Fine mapping of the dominant potyvirus resistance gene Pvr7 reveals a relationship with Pvr4 in Capsicum annuum. Phytopathology 108, 142–148. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-07-17-0231-R

Vinodhini, J., Rajendran, L., Abirami, R., and Karthikeyan, G. (2021). Co-existence of chlorosis inducing strain of Cucumber mosaic virus with tospoviruses on hot pepper (Capsicum annuum) in India. Sci. Rep. 11, 8796. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88282-9

Walker, P. J., Siddell, S. G., Lefkowitz, E. J., Mushegian, A. R., Adriaenssens, E. M., Dempsey, D. M., et al. (2021). Changes to virus taxonomy and to the International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Arch. Virol. 166, 2633–2648. doi: 10.1007/s00705-021-05156-1

Wang, A. and Krishnaswamy, S. (2012). Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-mediated recessive resistance to plant viruses and its utility in crop improvement. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 795–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00791.x

Wei, J., Li, Y., Chen, X., Tan, P., Muhammad, T., and Liang, Y. (2024). Advances in understanding the interaction between Solanaceae NLR resistance proteins and the viral effector Avr. Plant Signal Behav. 19, 2382497. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2024.2382497

Yoon, Y.-J., Venkatesh, J., Lee, J.-H., Kim, J., Lee, H.-E., Kim, D.-S., et al. (2020). Genome editing of eIF4E1 in tomato confers resistance to pepper mottle virus. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 1098. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01098

Zhan, X., Zhang, F., Zhong, Z., Chen, R., Wang, Y., Chang, L., et al. (2019). Generation of virus resistant potato plants by RNA genome targeting. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 1814–1822. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13102

Zhang, T., Zheng, Q., Yi, X., An, H., Zhao, Y., Ma, S., et al. (2018). Establishing RNA virus resistance in plants by harnessing CRISPR immune system. Plant Biotechnol. J. 16, 1415–1423. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12881

Zhao, C., Lou, H., Liu, Q., Pei, S., Liao, Q., and Li, Z. (2024). Efficient and transformation-free genome editing in pepper enabled by RNA virus-mediated delivery of CRISPR/Cas9. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 66, 2079–2082. doi: 10.1111/jipb.13741

Keywords: antiviral defense strategies, Capsicum annuum, dominant resistance, plant viruses, recessive resistance

Citation: Shilpha J and Kang W-H (2025) Molecular and genomic insights into viral resistance in Capsicum spp.: pathogenesis, defense mechanisms, and breeding innovations. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1716114. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1716114

Received: 10 October 2025; Accepted: 07 November 2025; Revised: 31 October 2025;

Published: 01 December 2025.

Edited by:

Sumit Jangra, University of Florida, United StatesReviewed by:

Anna Taglienti, Council for Agricultural Research and Agricultural Economy Analysis | CREA, ItalyMuhammad Aamir Manzoor, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China

Copyright © 2025 Shilpha and Kang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Won-Hee Kang, d2hrYW5nQGdudS5hYy5rcg==

Jayabalan Shilpha

Jayabalan Shilpha Won-Hee Kang

Won-Hee Kang