- 1State Key Laboratory of Breeding Biotechnology and Sustainable Aquaculture, Wuhan, China

- 2Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan, China

- 3University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

Submerged macrophytes play a pivotal role in maintaining the clear-water state and enhancing biodiversity in wetland ecosystems. However, the environmental mechanisms underlying their assemblage and biomass patterns remain poorly resolved in continental alkaline wetlands. Here, we conducted a 27 hydrochemical parameters analysis and dissected its relations with the distribution of submerged macrophytes in Momoge wetland of the Songnen Plain, Northeastern China. The results revealed that rock weathering and evaporation-crystallization processes jointly regulated the baseline alkalinity and salinity of the water, thereby determining 62.5% species of submerged macrophytes capable of utilizing HCO3- as an alternative carbon source. In contrast, nutrient inputs and wind-induced resuspension caused fluctuations in physicochemical conditions between light (50 < TLI ≤ 60) and moderate (60 < TLI ≤ 70) eutrophic states, resulting in Potamogeton pectinatus, Najas marina, and Chara spiralis thriving in nutrient-rich, low-transparency waters, whereas Utricularia aurea and Ceratophyllum demersum favored clearer and less nutrient-enriched conditions. These findings highlight a two-tiered environmental control over submerged macrophytes in boreal wetlands, whereby geochemical processes shape species assemblages, and nutrient dynamics and physical disturbance drive biomass allocation. We propose a restoration strategy that combines species configuration and pilot selection, prioritizing HCO3--utilizing pioneer species in degraded zones to gradually re-establish submerged macrophytes and ecosystem functions.

1 Introduction

Wetlands are vital ecosystems that provide numerous environmental services, including biodiversity conservation, water quality regulation, carbon sequestration, and flood control (Mitsch, 1993; Mitsch and Gosselink, 2000; Mitsch et al., 2015; Mio et al., 2024). As one of the most productive ecosystems on Earth, wetlands support a diverse range of plant and animal species and are considered biodiversity hotspots (Berde et al., 2022; Sharma and Naik, 2024). Submerged macrophytes, grow beneath the water surface, play a crucial role in wetland ecosystems by regulating water quality, stabilizing sediments, and enhancing biodiversity (Reid et al., 2019; Jeppesen et al., 2012; Chao et al., 2024). By occupying unique ecological niches, submerged macrophytes contribute to the transition from turbid to clear-water states (Ibáñez and Peñuelas, 2019; Zhang et al., 2022), thereby improving the overall health and functioning of aquatic ecosystems (Han et al., 2024; Jeppesen et al., 2012). Given their ecological importance, the decline in submerged macrophyte communities represents a significant threat to wetland health, calling for effective restoration strategies (Rodrigo, 2021).

Despite the crucial role submerged macrophytes play in wetland ecosystems, they face increasing threats from anthropogenic activities (Zhang et al., 2024), such as land-use change (Bomfim et al., 2025), nutrient loading (Dong et al., 2022), groundwater overexploitation (Puche et al., 2024), and climate change (Lind et al., 2022). These stressors, particularly nutrient enrichment and water quality degradation, have led to the decline of submerged macrophytes in many wetlands, disrupting ecosystem services and biodiversity (Liu et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2023). The ongoing degradation of submerged macrophytes highlights the need for a comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence their distribution and abundance, which is critical for developing targeted wetland restoration strategies. Submerged macrophytes interact closely with their aquatic environment (Jeppesen et al., 2012), and their growth (Wang et al., 2020), species composition (Liu et al., 2020), and biomass distribution (Wang et al., 2015) are strongly influenced by hydrochemical properties such as pH, alkalinity, salinity, and nutrient concentrations. In particular, water chemistry plays a central role in shaping the structure of submerged macrophytes (Bornette and Puijalon, 2011; Ferreira et al., 2018). In regions with high alkalinity and salinity, submerged macrophytes often rely on HCO3- as an alternative carbon source for photosynthesis (Iversen et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2024), which enables them to thrive in these environments (Maberly et al., 2015; Szabó et al., 2025). Furthermore, nutrient loading—especially nitrogen and phosphorus—can drive shifts in submerged macrophytes, favoring species that are more tolerant of eutrophic conditions (Ibáñez and Peñuelas, 2019). Understanding the complex interactions between inorganic carbon availability, nutrient loading, and hydrochemical factors is essential for predicting how submerged macrophyte communities will respond to environmental changes.

Although there has been significant research on the role of hydrochemical properties in shaping submerged macrophytes (Søndergaard et al., 2010, 2022; Szoszkiewicz et al., 2025), few studies have examined the specific interactions between water chemistry and submerged macrophytes in boreal wetland ecosystems, where species composition and water quality are highly sensitive to both natural processes and anthropogenic pressures (García Molinos et al., 2016; Xia et al., 2022). Boreal wetlands, such as those distributed in the Songnen Plain, are particularly vulnerable to changes in water chemistry due to nutrient enrichment (Luo et al., 2025), land-use changes (Chen et al., 2018), and fluctuating water tables (Zhang et al., 2015). Despite this, comprehensive studies that assess the relationships between hydrochemical parameters and submerged macrophytes in these regions are limited. This study aims to fill this gap by investigating the interactions between hydrochemical properties and submerged macrophyte distribution in the Momoge wetland of the Songnen Plain, Northeast China. By addressing the influence of hydrochemical properties on submerged macrophytes, this study will contribute to a better understanding of the environmental factors that govern the distribution of submerged macrophytes. Furthermore, it will provide practical guidance for restoring submerged macrophytes in boreal wetlands, with the ultimate goal of enhancing biodiversity, improving water quality, and ensuring the long-term sustainability of these vital ecosystems in the Songnen Plain wetlands.

2 Methods

2.1 Study area

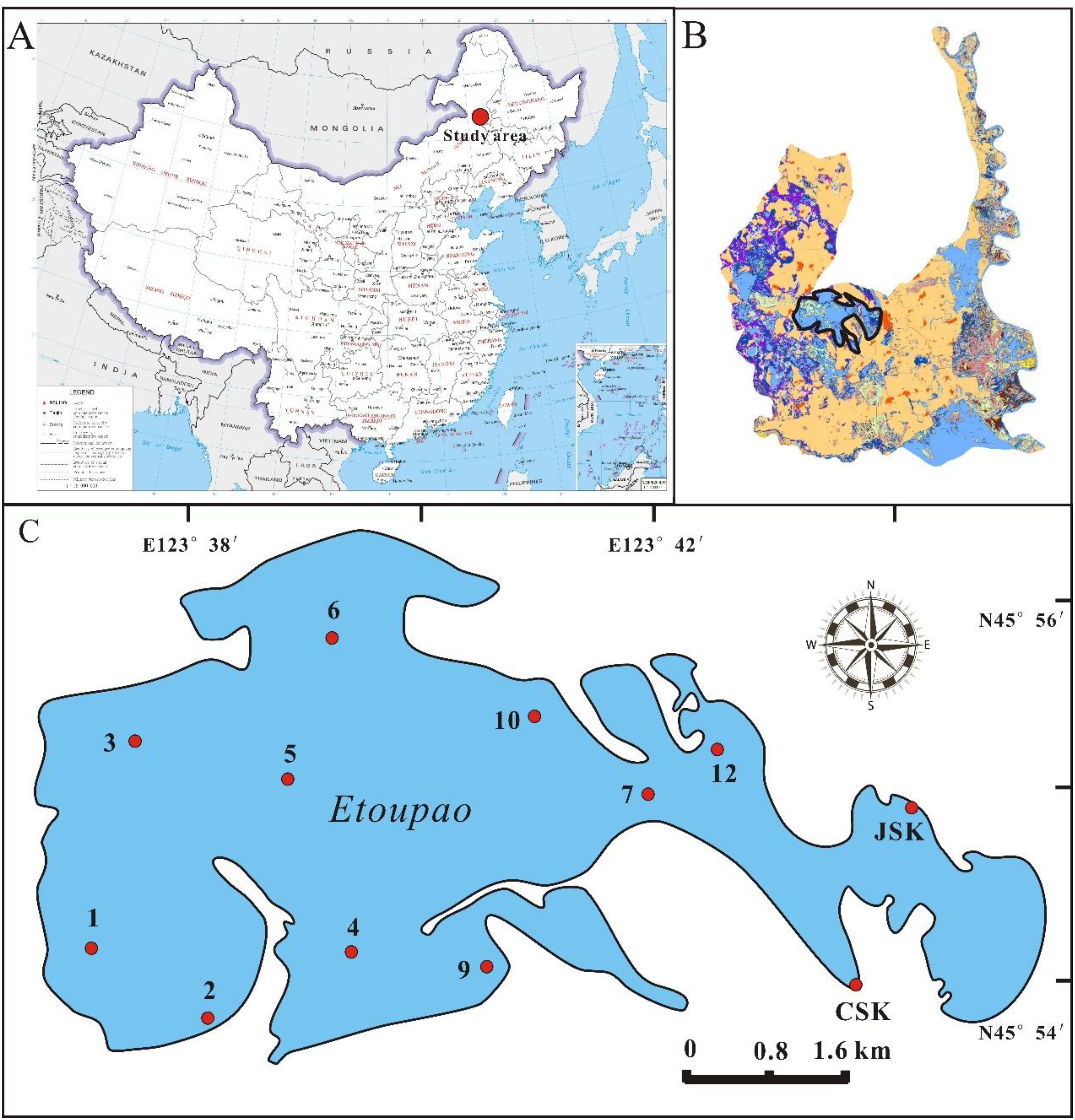

Momoge National Nature Reserve is located on the western margin of Songnen Plain, with the coordination of 45°12’25”N to 46°18’0”N, 123°27’0”E to 124°04’33”E and the average elevation is 142 m. The total area is 1.44×103 km2, in which 80% consists of wetlands, such as lakes, rivers, and marshes. Etoupao which is the biggest one in Momoge wetland was chosen as the study area and the grid method (Supplementary Figure S1) was adopted to set up the twelve sampling sites distributed homogeneity (Figure 1). Typical temperate continental monsoon climate governs this region which has a frost-free period of 137 days, and the annual average temperature, solar radiation, precipitation, and evaporation are 4.2 °C, 5220 MJ m-2, 392 mm, and 1553 mm, respectively (Wei et al., 2019). In this nature reserve, approximately 60–000 residents live in and the land-use has been significantly changed for the purpose of raise yield (Jiang et al., 2007). It’s reported that the farmland and alkali-land increased by 168.9 km2 and 143.7 km2 in the twenty years (Li et al., 2018). Located in northeastern China where the arid fragile ecosystem, wetlands play an important role in regulating regional climate, increasing local rainfall, reducing sand-blown weather, elevating crop yield and protecting biodiversity etc., especially serve as a significant habitat and stopover site for the Siberian Crane (Jiang et al., 2016), which is the world’s most endangered crane species.

Figure 1. Situation of Momoge National Nature Reserve in China (A) and the study area in Momoge wetland circled in solid black line (B), and the distribution of sampling sites in Etoupao (C).

2.2 Field methods

Due to the water areas are frozen-up from late October to early May the following year including spring and winter (Huang et al., 2005), sampling surveys were conducted on September 6th-7th, 2017 (referred to as “Autumn”) and July 26th-27th, 2018 (referred to as “Summer”), and the water depth ranged from 0.30 to 1.50 m in the wetland, with a mean value of 0.98 m. At each site, physicochemical parameters of surface water samples were divided into two parts, in situ measurement and laboratory analysis. Water temperature (T), electrical conductivity (Ec), pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) and salinity (Sal) were recorded in situ using portable equipment Manta YSI (Eureka, USA). Water transparency (Trans) and depth were measured by Secchi plate and depth meter (Speedtech, Japan), respectively. Water samples were collected and stored in a portable icebox for laboratory analysis of major water elemental components (K+, Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, SO42-, Cl-, HCO3- and CO32-), followed by the determination of total nitrogen (TN), nitrate nitrogen (NO3-N), nitrite nitrogen (NO2-N), ammonium nitrogen (NH4-N), total phosphorus (TP), dissolved inorganic phosphorus (DIP), chemical oxygen demand (COD), chlorophyll a (Chla), alkalinity (Alk) and total suspended solid (TSS).

Submerged macrophyte surveys were carried out by the quadrat method (Wang et al., 2015). A criterion comprising as many species as possible within a certain area was obeyed after walking through the wetland to evaluate the structure, composition, and variability of submerged macrophytes (Klee et al., 2019). At each sampling site, three quadrats were randomly selected with the size of 1 m×1 m, and to lower down the destruction of submerged meadows, five sub-quadrats (0.2 m×0.2 m) which distributed in the four angles and center of the quadrat were designated to harvest all the submerged macrophytes (Wang et al., 2015). After washed and wiped out all the water, fresh weights were calculated by electronic scale according to different species. Consequently, fresh weights for different species, average biomass at each sampling site, and composition of each quadrat were recorded at all sampling sites.

2.3 Laboratory analysis

The water samples were analyzed for K+, Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ by Inductively Coupled Plasma-optical emission spectroscopy Optima 8000DV (PekinElmer, USA). The SO42- and Cl- were measured by Advanced Compact Ion chromatography (Metrohm, Switzerland). HCO3- and CO32- as well as Alk were titrated by sulphuric acid with a concentration of 0.025 mol L-1 (Wang et al., 2020). In accordance with the 2002 “Water and Wastewater Monitoring and Analysis Methods” released by the Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China (Lu et al., 2016), TN, NO3-N, NO2-N, NH4-N, TP, and DIP were determined by alkaline potassium persulfate digestion-UV spectrophotometric method, spectrophotometric method phenol disulfonic acid, spectrophotometric method with sulphanilamide and coupling with N-(1-napththyl)-ethylenediamine, Nessler’s reagent spectrophotometric, and ammonium molybdate spectrophotometric method, respectively. COD, Chla and TSS were determined by the potassium dichromate method (Lu et al., 2016), spectrophotometric method (Richardson et al., 2002), and gravimetric method (Lu et al., 2016). The nutrient levels were classified as oligotrophic (0.0-1.0 mg L-1) and mesotrophic (1.1-5.0 mg L-1) for nitrate concentrations and eu-polytrophic (0.031-0.1 mg L-1) and polytrophic (>0.1 mg L-1) for total phosphorus concentrations (Li et al., 2007), and the trophic level index (TLI) was calculated according to the Chla, TP, TN, SD, and COD (Carlson, 1977; China National Environmental Monitoring Centre, 2001).

pH-drift analysis was performed to test the inorganic carbon utilization by submerged macrophytes in the process of photosynthesis (Maberly, 1996). Fresh apical shoots were chosen as materials and wash out the attachments, then rinsed twice in the test solution which comprised equimolar concentrations of NaHCO3 and KHCO3 with the concentration of 1.0 mmol L-1. Plant shoots with the length of 6 cm were transferred into 30 mL glass tubes with stopper where had injected 25 mL Na/KHCO3 solution with the concentration of 1.0 mmol L-1 and the residual space were to alleviate the oxygen tension in solution (Yin et al., 2017). The culture systems were incubated in artificial climate incubator (Yiheng, Shanghai) at 25 °C and 75 µmol photon m-2 s-1. After 24 h continuous incubation, the final pH (there was no further change) was determined by Manta YSI (Eureka, USA).

2.4 Data analyses

Firstly, the water type was analyzed and visualized by GW_Chart, a program for creating specialized graphs according to the concentrations of K+, Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, HCO3-, CO32-, SO42-, Cl- and TDS. To trace the origins of the major ions and their controlling factors in the water columns, the Gibbs model (Gibbs, 1970) and ion ratios diagrams (Lakshmanan et al., 2003) were generated by Origin 85, respectively. Multivariate statistical analysis of the water physicochemical parameters was executed by SPSS 18, and the heatmaps were generated by R with corrplot packages to cluster the water physicochemical characteristics. Secondly, the relative frequency (RF), relative biomass (RB), and dominance (D) of submerged macrophytes were calculated following the method by Wang et al. (2015). And surfer 9 was employed to simulate the biomass distribution in the wetland. Finally, the canonical correspondence analysis was performed to figure out relationships between water physicochemical properties and biomass distribution of submerged macrophytes by Canoco for Windows 4.5. In the processes, CorelDRAW X4 was used not only to draw the sampling distribution map but also to integrate several figures into a complex.

3 Results

3.1 Hydrochemical properties

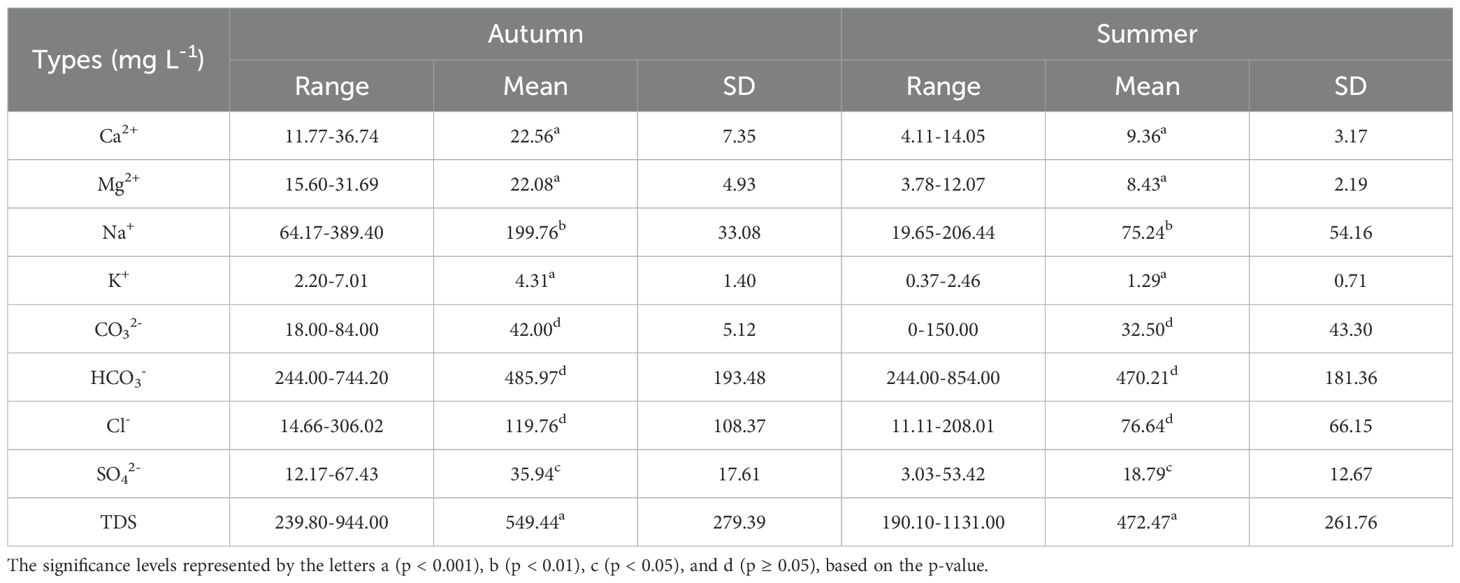

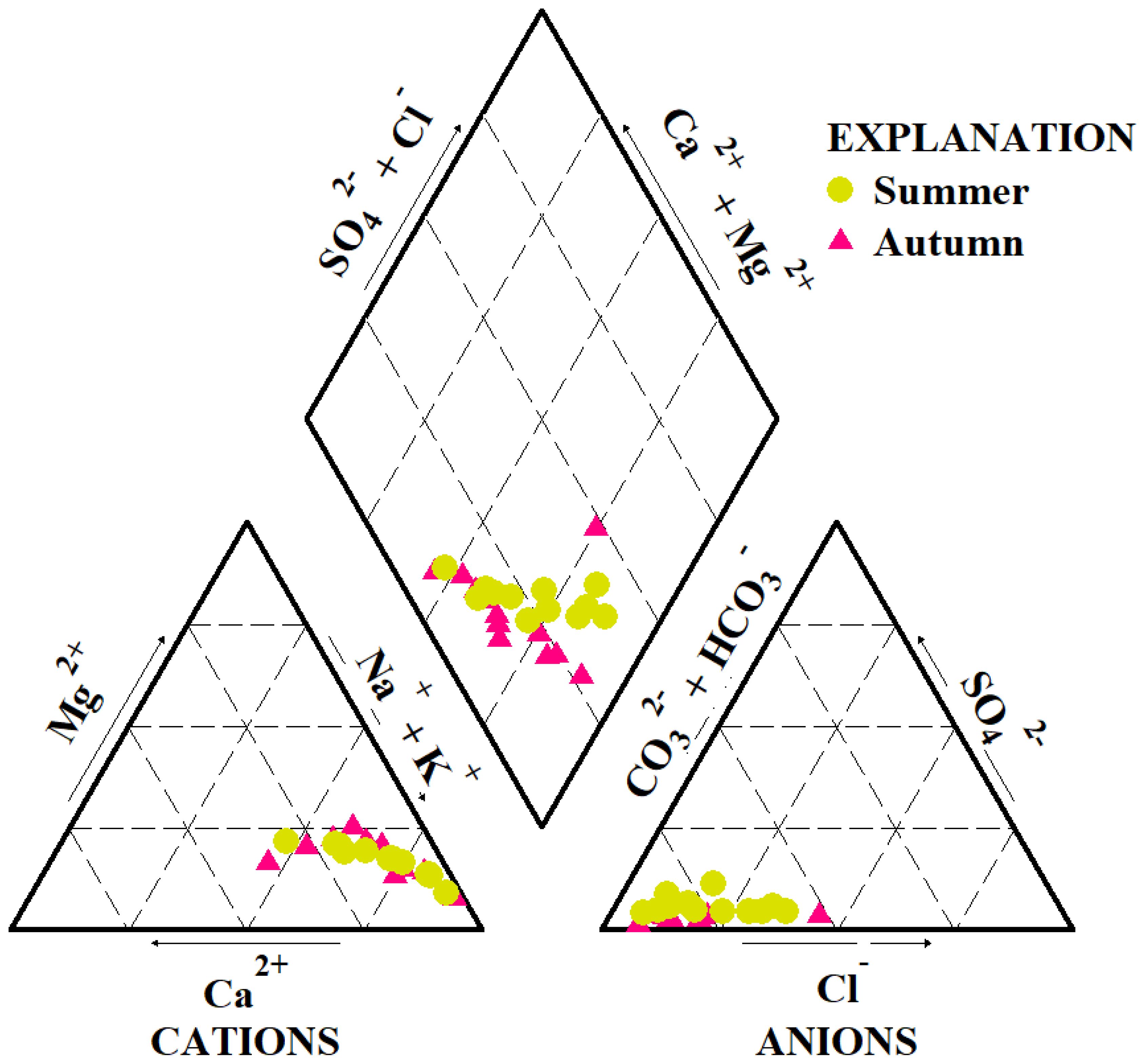

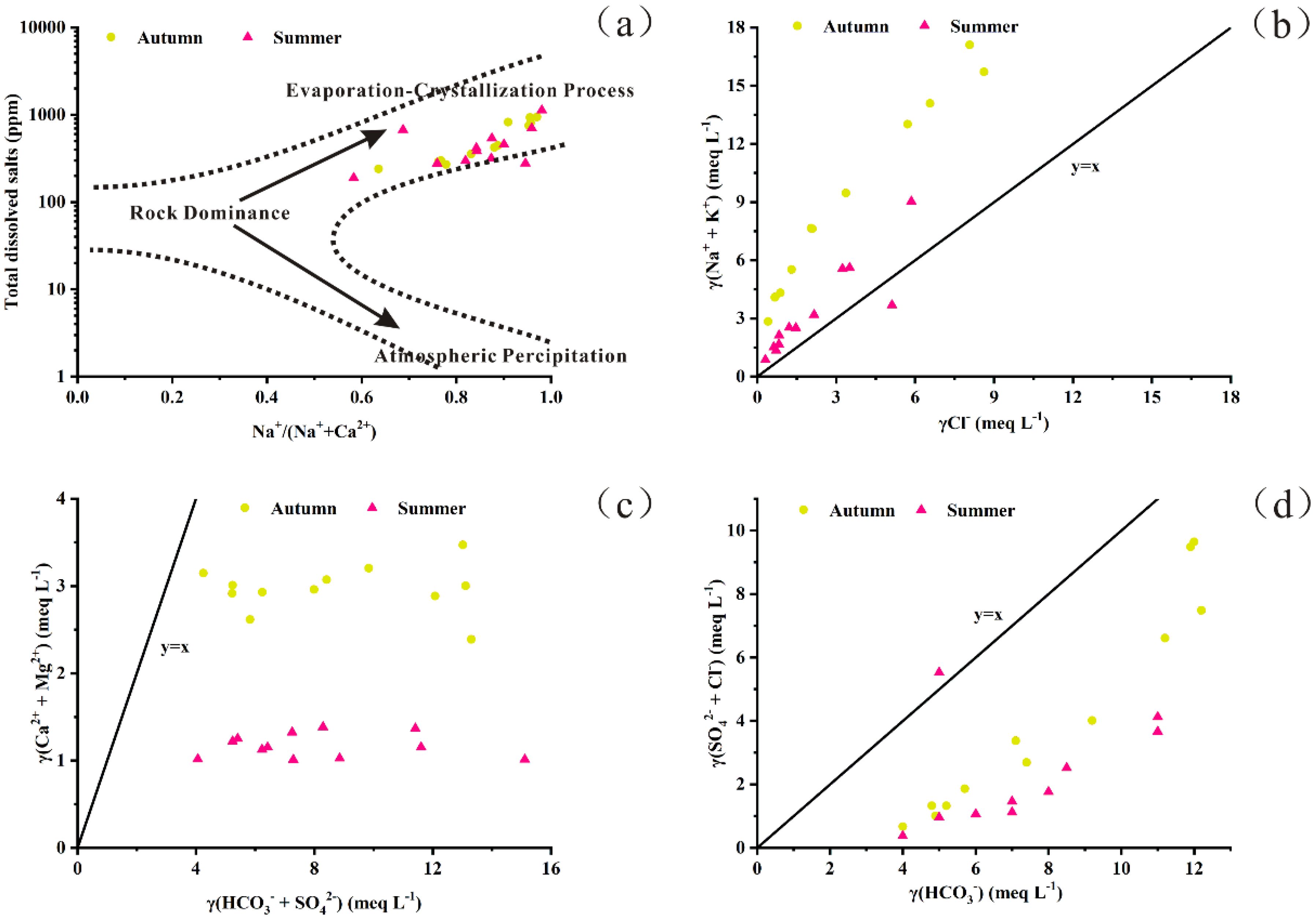

The abundance of cations followed the order Na+ > Mg²+ > Ca²+ > K+, while anions were dominated by HCO3- > Cl- > CO3²- > SO4²- in both sampling seasons. Overall, mean ion concentrations were higher in autumn than in summer (Table 1). Although the concentrations of major ions varied seasonally, the Piper diagram (Figure 2) indicated that the water consistently exhibited HCO3-type and Cl-type characteristics throughout the year. Ion ratio analyses further revealed distinct geochemical patterns. According to the Gibbs model, nearly all values clustered near 1 (Figure 3a). The ratios of γ(Na+ + K+)/γCl- were primarily distributed above the 1:1 equilibrium line (Figure 3b), suggesting enrichment of sodium and potassium relative to chloride. In contrast, both γ(Ca²+ + Mg²+)/γ(HCO3- + SO4²-) and γ(SO4²- + Cl-)/γHCO3- ratios were below the equilibrium line (Figures 3c, d), indicating that carbonate weathering and evaporative processes were dominant.

Figure 3. Relationships between the ratios of selected ions. (a) The diagram of Gibbs model. (b) The ratio between γ(Na++K+) and γCl-. (c) The ratio between γ(Ca2++Mg2+) and γ(HCO3-+SO42-). (d) The ratio between γ(SO42-+ Cl-) and γHCO3-. The y=x denotes the equilibrium line.

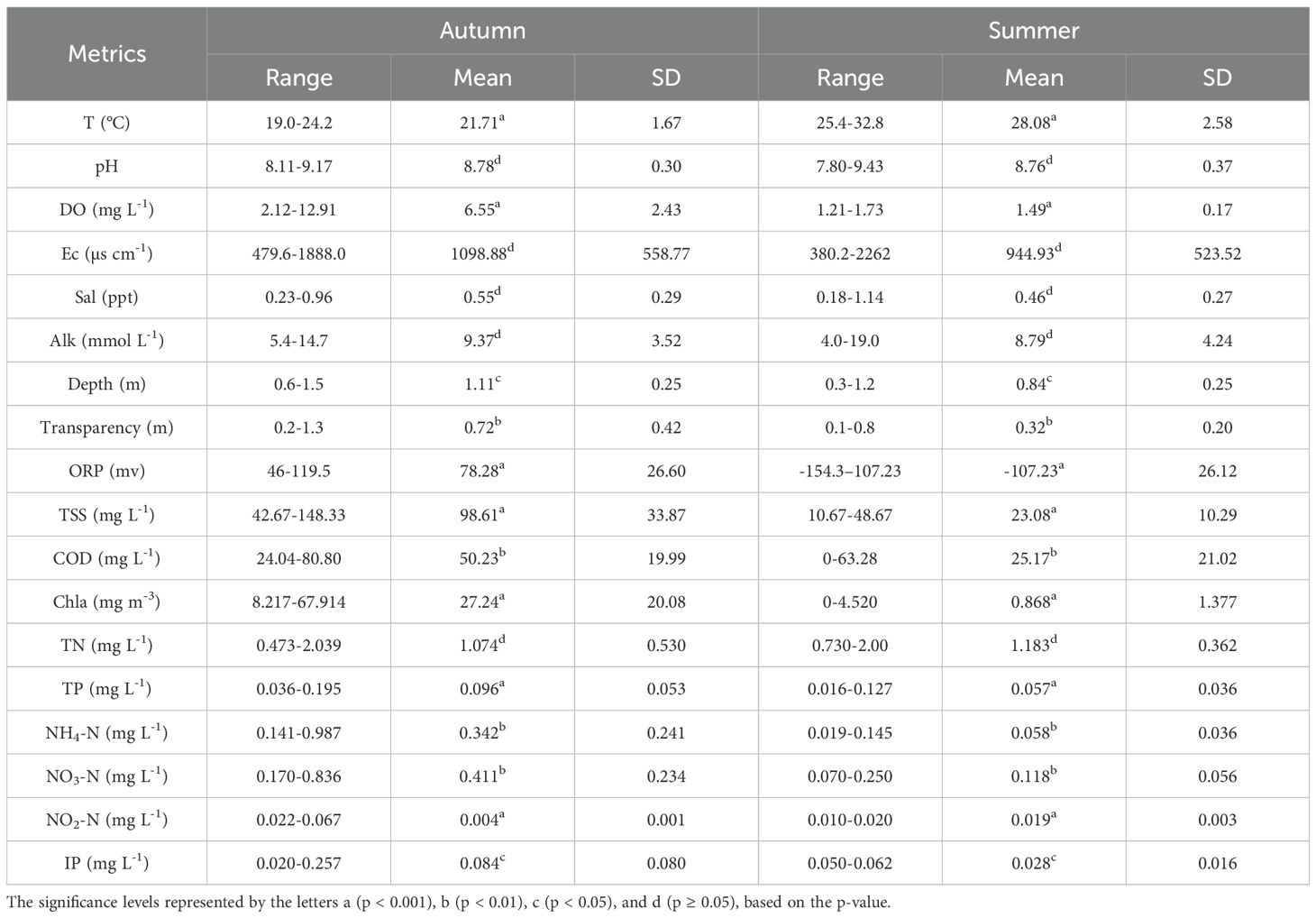

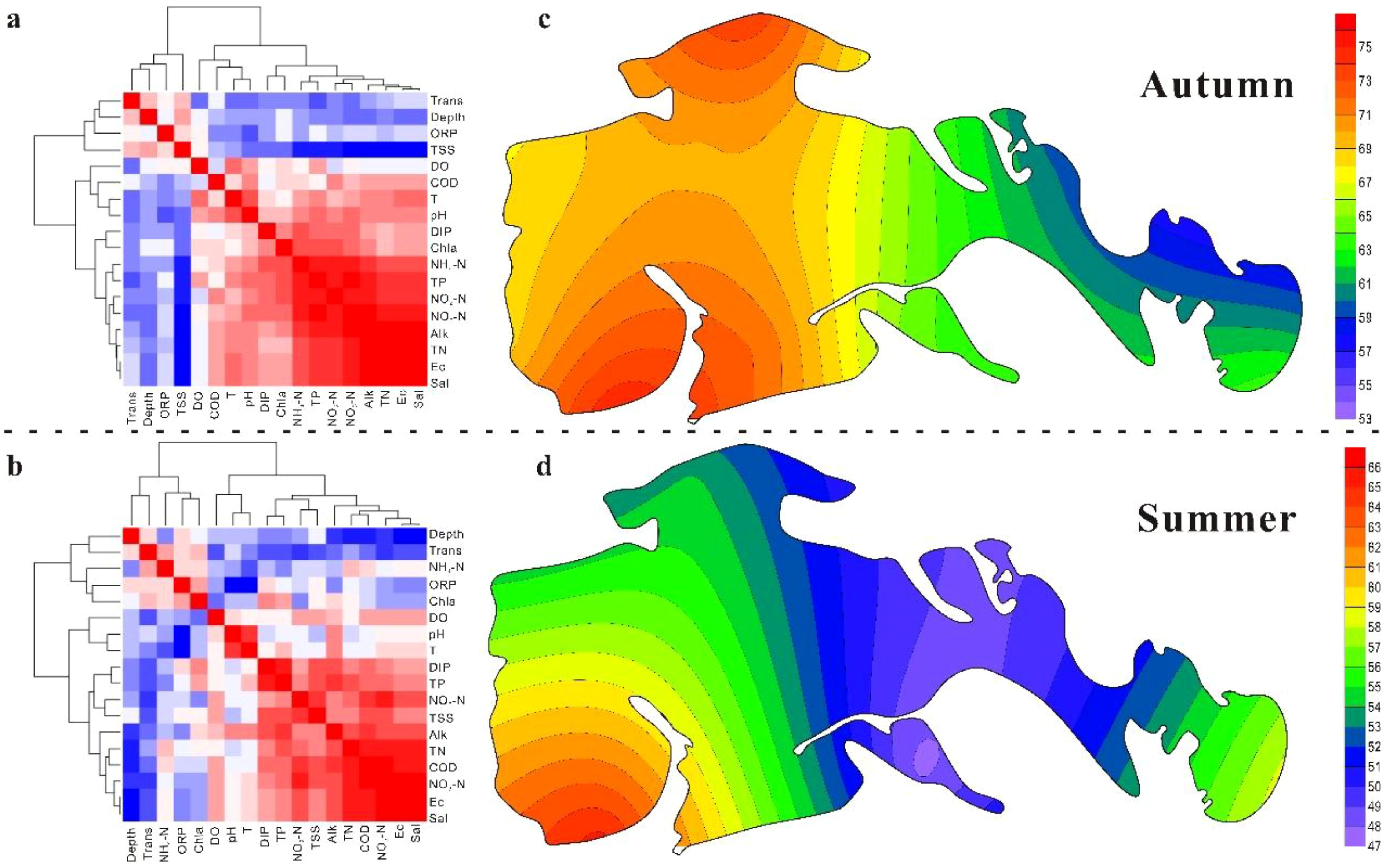

Most water physicochemical parameters exhibited higher values in autumn than in summer (Table 2). Among them, DO, Trans, ORP, TSS, COD, Chl-a, TP, NH4-N, NO3-N, NO2-N, and DIP showed significant seasonal differences. Correlation and cluster analyses revealed that the measured variables could be divided into two major groups in both seasons (Figure 4a, b). The first group included Trans, Depth, and ORP, while the second group comprised Sal, Ec, Alk, TN, TP, COD, NO3-N, NO2-N, and DIP. These two groups were negatively correlated with one another. Within the second group, TN, TP, COD, NO3-N, NO2-N, and DIP were strongly positively correlated with Sal, Ec, and Alk. The principal component analysis further identified four principal components (Supplementary Figures S2, S3), explaining 83.45% and 84.30% of the total variance in autumn and summer, respectively. In autumn, the first component—dominated by pH, Ec, Sal, Alk, TSS, Chl-a, TN, TP, NH4-N, NO3-N, NO2-N, and DIP—accounted for 53.30% of the variance, far exceeding the combined 30.15% explained by the other three components. In summer, the first component (Ec, Sal, Alk, Depth, Trans, TSS, COD, TN, TP, NO3-N, and DIP) explained 42.30% of the variance. From the perspective of individual nutrient indicators, mean NO3-N concentrations corresponded to mesotrophic conditions, while TP levels were classified as eu-polytrophic in both seasons. In autumn, 50% of sampling sites were in a mesotrophic state based on NO3-N, whereas this proportion increased to 66.67% in summer. Conversely, TP showed higher levels of eutrophication, with 41.67% of sites classified as polytrophic in autumn and 83.33% as eu-polytrophic in summer. According to the TLI classification (Supplementary Figure S3; Figures 4c, d), the wetland was classified to middle eutropher and light eutropher in autumn and summer, respectively. Collectively, these findings indicate that the Ec, Sal, Alk, TSS, TN, TP, and NO3-N were the dominant factors controlling the water quality in the wetland.

Figure 4. Correlation and cluster analysis of water chemistry (a, b) and the corresponding TLI in the wetland (c, d). The dashed line is the boundary of the autumn (Upper parts) and summer (Lower parts).

3.2 Species assemblage and biomass distribution

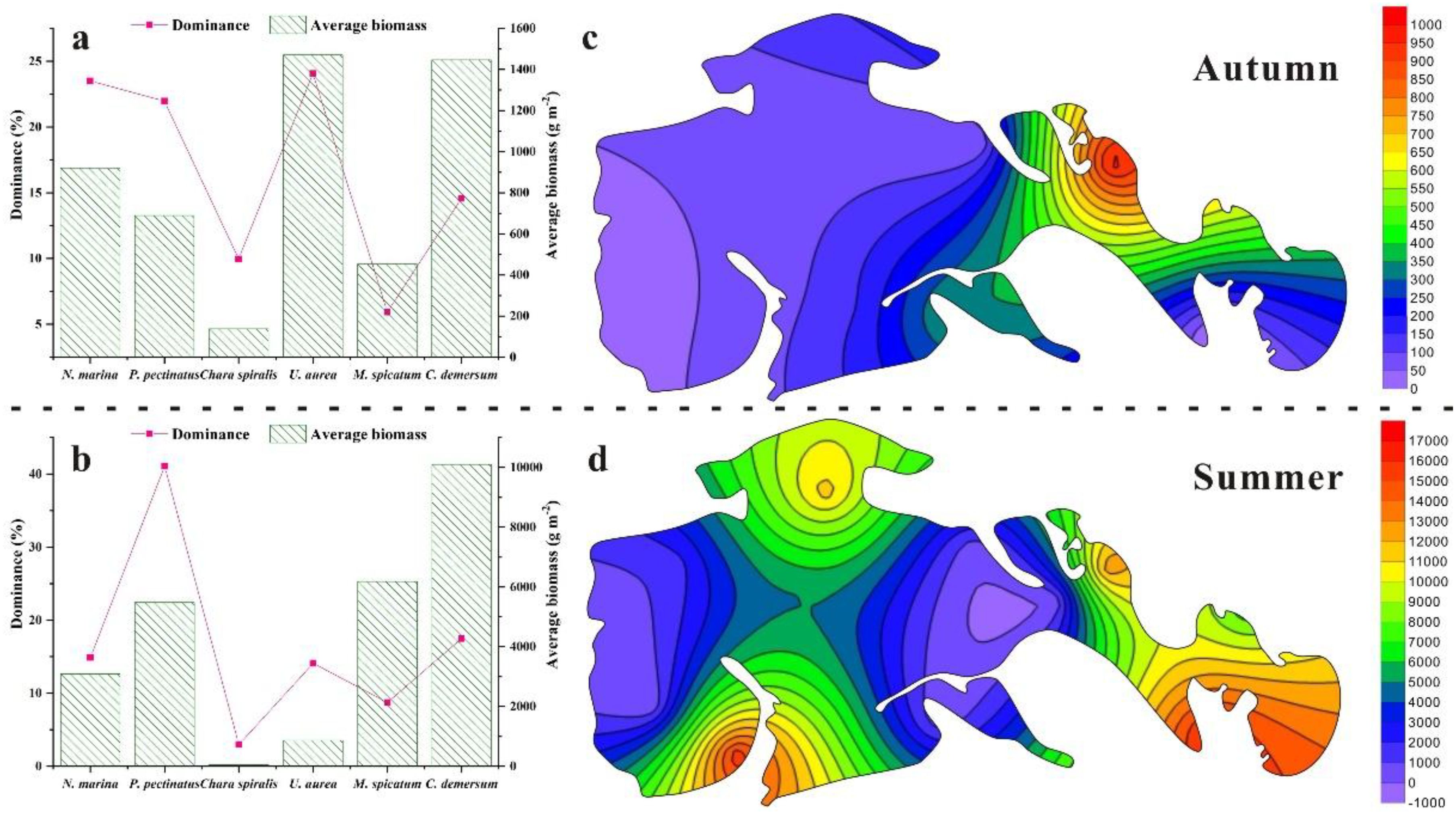

Field surveys revealed that the species composition of submerged macrophytes remained relatively consistent across years, whereas species dominance and average biomass exhibited pronounced seasonal variations. Across the two survey periods, a total of eight species belonging to six families were recorded (Table 3). Among these, N. marina, P. pectinatus, U. aurea, C. demersum, M. spicatum, and Char. spiralis were consistently present in both surveys. In contrast, P. distinctus and P. crispus appeared only sporadically and were restricted to specific seasons. In terms of species dominance, U. aurea was the most dominant species in autumn, accounting for 24.07% of the total relative dominance, followed by N. marina (23.51%), P. pectinatus (21.97%), C. demersum (14.57%), Char. spiralis (9.95%), and M. spicatum (5.93%) (Figure 5a). In summer, the dominance hierarchy shifted, with P. pectinatus emerging as the leading species (41.07%), followed by C. demersum (17.49%), N. marina (14.89%), U. aurea (14.09%), M. spicatum (8.72%), and Char. spiralis (2.98%) (Figure 5b). Patterns of biomass distribution also varied substantially between seasons. In summer, C. demersum exhibited an overwhelming dominance, with a biomass of 10,100.01 g/m², whereas Char. spiralis recorded the lowest biomass at 44.42 g/m². In autumn, U. aurea ranked first with 1,471.02 g/m², followed by C. demersum (1,446.75 g/m²), N. marina (920.28 g/m²), P. pectinatus (689.75 g/m²), M. spicatum (453.13 g/m²), and Char. spiralis (137.94 g/m²). Spatially, average biomass was highest in sheltered bay areas and lowest in open water zones, with a clear east-west gradient characterized by higher biomass in the eastern regions and lower biomass in the western regions (Figures 5c, d). This spatial pattern reflects the influence of hydrodynamic stability and environmental heterogeneity on submerged macrophyte growth and distribution.

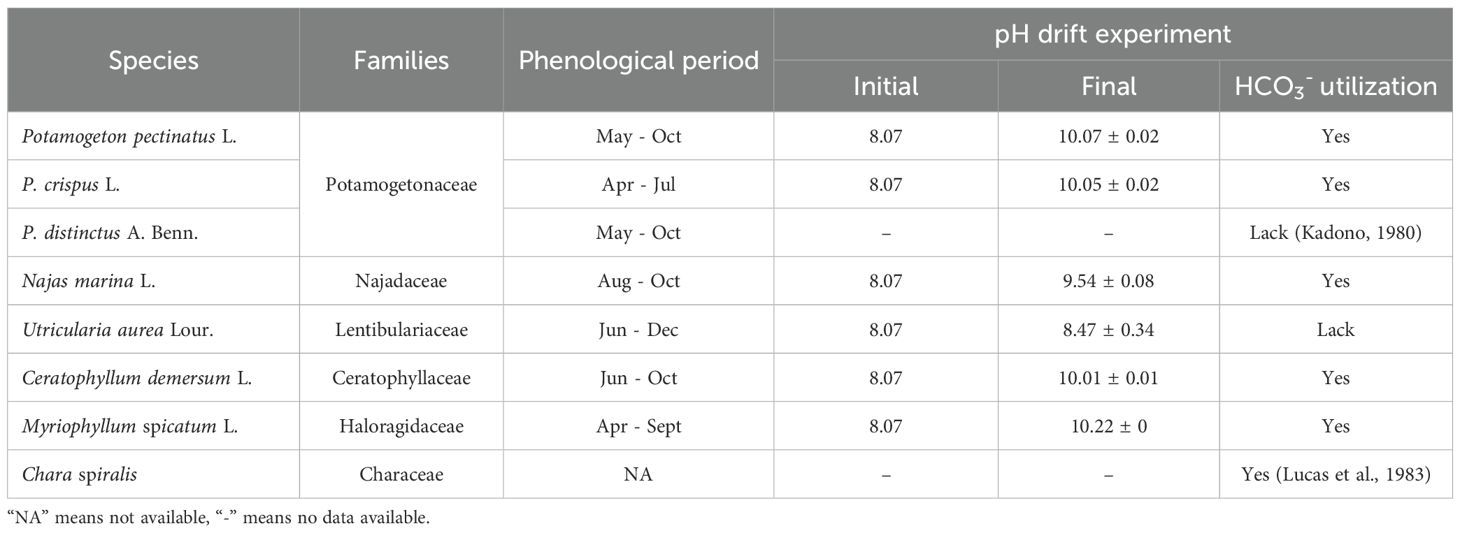

Table 3. Classification of the recorded submerged macrophytes and values of the pH drift experiment.

Figure 5. Species assemblage and biomass distribution in Autumn and Summer (The dashed line is their boundary). Figures with lowercase (a, b) represent the dominance and average biomass, and figures with the lowercase (c, d) represent the biomass distribution simulated from the average biomass in each sampling site.

3.3 Relationship between hydrochemical properties and submerged macrophytes

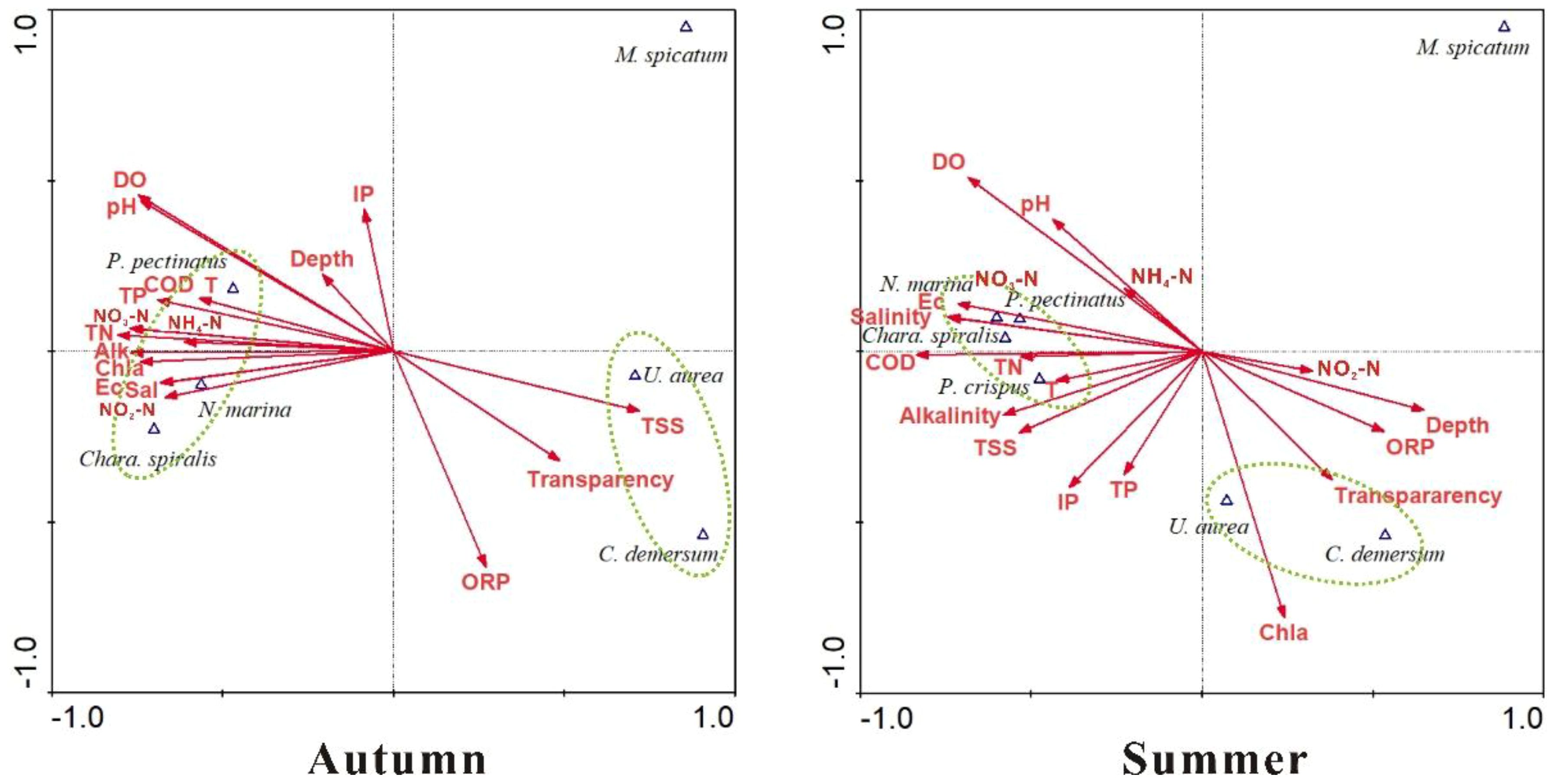

The pH-drift experiments (Table 3) revealed that the M. spicatum, C. demersum, P. pectinatus, P. crispus, and N. marina are capable of utilizing HCO3- as an alternative carbon source, whereas U. aurea lacks this ability. The canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) further demonstrated that submerged macrophytes could be classified into three distinct groups based on the relationships between their biomass distribution and water physicochemical properties (Figure 6). These groupings were highly consistent with the results of the cluster analysis of hydrochemical characteristics. The first group, consisting of P. pectinatus, N. marina, and Char. spiralis—species present in both seasons—was strongly influenced by water column parameters such as T, pH, Ec, DO, Sal, Alk, COD, TN, TP, and NO3-N. The second group, represented by U. aurea and C. demersum, showed positive correlations with water Trans and ORP in both seasons, though with slight seasonal differences. In contrast, the third group, consisting solely of M. spicatum, exhibited minimal correlation with hydrochemical parameters, indicating its broad adaptability to varying environmental conditions.

Figure 6. Canonical correspondence analysis between the water physicochemical variables and biomass distribution of the mutual species in both seasons. Submerged macrophytes circled in the same dashed ellipse are a group.

In summary, based on their adaptive capacity to water chemistry, submerged macrophytes in the study area can be ranked into three categories. M. spicatum demonstrates the highest ecological resilience, thriving under a wide range of environmental conditions. The intermediate group includes P. pectinatus, N. marina, and Char. spiralis, which have moderate tolerance and respond strongly to nutrient-related parameters. Finally, U. aurea and C. demersum are the most sensitive species, requiring higher water quality, particularly high transparency, to maintain growth and biomass stability.

4 Discussion

4.1 Factors governing water physicochemical properties

The geological background forms the foundation of the ecological environment and plays a vital role in understanding the formation and evolution of fundamental hydrochemical properties (Iversen et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023). This is particularly important in wetlands, where surface water and groundwater interact within a watershed, creating complex hydrochemical dynamics (Volik et al., 2023). At the global scale, the primary factor controlling solute chemistry is lithology, with natural waters strongly influenced by rock weathering within a given basin (Lakshmanan et al., 2003). Major ions, including K+, Na+, Ca²+, Mg²+, Cl-, SO4²-, HCO3-, and CO3²-, constitute a significant proportion of the total dissolved salts in wetland waters, and their concentrations largely depend on hydrogeochemical processes occurring in both surface and subsurface environments (Xiao et al., 2015). Consequently, analysis of major ion concentrations provides critical insights into their sources and governing processes. In this study, the γ(Na+ + K+)/γCl- scatter diagram (Figure 3b) showed that nearly all sampling points were distributed above the 1:1 equilibrium line, indicating halite dissolution. Moreover, the relatively high sodium concentration compared to chloride suggests the contribution of silicate weathering. The abundance of Na+, Ca²+, and Mg²+ is associated with clay minerals such as montmorillonite, illite, and chlorite (Kumar et al., 2009). The γ(Ca²+ + Mg²+)/γ(HCO3- + SO4²-) scatter diagram is particularly useful for distinguishing between carbonate and silicate weathering processes (Datta and Tyagi, 1996). In this study, both γ(Ca²+ + Mg²+)/γ(HCO3- + SO4²-) and γ(SO4²- + Mg²+)/γHCO3- ratios (Figure 3c, d) were below the equilibrium line, indicating that silicate weathering, evaporite dissolution, and carbonate weathering are the dominant sources of major ions. Together, these processes are responsible for the elevated alkalinity and salinity characteristic of wetland waters (Wang et al., 2009; Lehmann et al., 2023). Over the past few decades, global climate change driven by intensive human activities has profoundly altered precipitation patterns and thermal regimes (Bandh et al., 2021), disrupting balances that had persisted over geological timescales, particularly in the Northern Hemisphere (Nosetto et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2018). Based on analyses of global datasets including rain, river, lake, and ocean water samples, Gibbs (1970) proposed three primary mechanisms controlling surface water chemistry: atmospheric precipitation, rock dominance, and evaporation–crystallization processes. In the present study, the Gibbs plot (Figure 3a) indicates that evaporation–crystallization is the dominant mechanism shaping water chemistry, consistent with the wetland waters are both saline and alkaline. The difference between precipitation and evaporation is one of the main drivers for the variations in water chemistry between seasons. Long-term climate records show a declining trend in annual precipitation and a simultaneous increase in atmospheric temperature over the past 30 years in the study area (Cui et al., 2016). These conditions have intensified the evaporation–crystallization process, further enhancing the fundamental water chemistry characteristics, particularly alkalinity and salinity. Thus, rock weathering combined with evaporation–crystallization processes constitute the primary control over water chemistry in this region.

Eutrophication, driven by excessive inputs of nitrogen and phosphorus, represents a pervasive and urgent global challenge to water quality (Barboza et al., 2019; Stevens, 2019). Classic studies of shallow lakes have shown that eutrophication drives ecosystem transitions between two alternative stable states: a clear-water state, characterized by high biodiversity and good water quality, and a turbid state, associated with low diversity and degraded ecological functions (Liu et al., 2020; Su et al., 2019). In this study, two distinct clusters of water quality were identified, corresponding to these states, suggesting that the studied wetland is currently undergoing a transitional phase from a clear to a turbid state. The primary drivers of this shift are anthropogenic activities, including excessive fertilizer use, industrial pollution, and wastewater discharge, which cause abrupt regime shifts (Folke et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2009). In the Momoge wetland, elevated concentrations of TN, TP, NO3-N, COD, TSS, NH4-N, NO2-N, and DIP are largely attributable to inputs from surrounding human activities, such as agriculture, industrial operations, and domestic activities in the watershed, particularly in the autumn, the drainage from the paddy directly flows into the Momoge wetland significantly increased the nutrient loading. This is one of the main reasons for the seasonal differences in nutrient states. In addition, the growing season of submerged macrophytes also contributes to the seasonal differences. Situated in the black soil region, the largest commercial grain production base in China (Cheng and Zhang, 2005), this area inevitably receives substantial nutrient runoff from agricultural practices and land-use change (Zou et al., 2018). For example, influent water samples showed TN and TP concentrations ranging from 0.92–9.85 mg L-¹ and 0.08–1.55 mg L-¹, respectively (Kou, 2012). Furthermore, 954 oil wells have been developed since 1986, with some extending into the core zone of the Momoge Nature Reserve (Wang et al., 2010), exacerbating contamination risks. In addition, wastewater from local residents directly contributes to water quality deterioration (Jiang et al., 2007). Beyond nutrient loading, external stressors such as wind-induced disturbance and the overexploitation of surface and groundwater also influence water quality by affecting transparency and water table fluctuations. This is supported by both cluster analysis (CA) and principal component analysis (PCA) results, which identify the TSS as one of the main controlling factors. Overall, at the regional scale, excessive nutrient inputs from anthropogenic sources, compounded by external physical disturbances, are driving a persistent and severe alteration of hydrochemical properties, causing the wetland to shift progressively from an oligotrophic to a eutrophic state.

4.2 Water physicochemical properties shape the distribution of submerged macrophytes

Submerged macrophytes interact closely with the aquatic environment in which they are anchored, and the dominance of particular species is largely a consequence of environmental selection (Liu et al., 2020). On the one hand, through photosynthesis, submerged macrophytes assimilate inorganic carbon, nutrients, and other dissolved minerals, thereby playing a crucial role in improving water quality and facilitating ecological restoration (Jeppesen et al., 2012). Conversely, the composition and distribution of submerged macrophyte communities are strongly shaped by the water environment, particularly the availability and form of dissolved inorganic carbon, which serves as the foundation for photosynthesis (Blowes et al., 2019). Unlike terrestrial plants, submerged macrophytes can utilize both CO2 and HCO3- as carbon sources. Numerous studies have highlighted that species capable of utilizing HCO3- exhibit greater adaptability to diverse aquatic environments (Maberly and Gontero, 2017; Wang et al., 2015; Yin et al., 2017). In this study, HCO3- overwhelmingly dominated over CO2 in the water column, a direct outcome of the region’s geological background. Results from our pH-drift experiments indicate that most species possess the ability to utilize HCO3-. Specifically, P. crispus, P. pectinatus, C. demersum, N. marina, and M. spicatum can use HCO3- as an alternative carbon source, consistent with the findings of Yin et al. (2017). In contrast, U. aurea cannot utilize HCO3-, likely because it has evolved an alternative nutritional strategy—capturing zooplankton as a supplementary food source (Rutishauser, 1993). Although HCO3- is generally less favorable for submerged macrophyte metabolism compared to CO2, the dominant species in this wetland have successfully adapted over long evolutionary timescales to thrive under these conditions. This indicates that alkaline water environments impose a strong environmental filter, favoring species capable of utilizing HCO3- while excluding those unable to do so.

The biomass distribution of submerged macrophyte species is strongly regulated by the eutrophication level of the waters they inhabit (Dar et al., 2014; Dudgeon et al., 2006). Excessive nutrient loading, particularly N and P, profoundly disrupts aquatic ecosystems, leading to reduced biodiversity and shifts in dominant species (Ibáñez and Peñuelas, 2019). Our results demonstrate that the hydrochemical properties of the wetland can be classified into two distinct categories, and the biomass patterns of submerged macrophytes closely align with this classification. P. pectinatus, N. marina, and Char. spiralis exhibited high biomass in nutrient-rich waters with elevated N and P concentrations, whereas U. aurea and C. demersum were primarily associated with clearer waters of higher transparency. This pattern suggests that as eutrophication intensifies due to human activities, the plant community will increasingly be dominated by species such as P. pectinatus, N. marina, and Char. spiralis, which are well-adapted to low-transparency, nutrient-enriched environments (Tobiessen and Snow, 1984; Agami et al., 1980). This phenomenon may contradict with some conventional recognitions, partly because the wetland is undergoing the regime shift processes. In addition to nutrient effects, external disturbances play a significant role in shaping plant distribution. Global climate change and overexploitation of water resources have caused a 70% loss of open water area in the wetland (Chen et al., 2018, 2020), consistent with our findings of increasing water salinity. Submerged macrophytes are highly sensitive to water table fluctuations and wind-induced disturbances (Blowes et al., 2019). Long-term meteorological data indicate that the mean annual wind speed in this region is 3.7 m s-¹ (Cui et al., 2016), creating intense wave turbulence that threatens the stability and anchorage of submerged macrophyte communities (Sand-Jensen and Pedersen, 1999). Field observations further confirm that submerged macrophytes thrive primarily in sheltered zones, such as areas surrounded by Phragmites australis or Scirpus planiculmis, which act as natural barriers that buffer wave action and create relatively stable microhabitats. These protective zones reduce mechanical stress, allowing for the establishment and persistence of submerged vegetation. In general, the distribution and biomass of submerged macrophytes in this wetland are shaped by the synergistic effects of nutrient enrichment and external disturbances. Nutrient enrichment, primarily from human activities, drives shifts toward communities dominated by eutrophication-tolerant species. External disturbances, such as wind-driven turbulence and water level fluctuations, further influence spatial heterogeneity by favoring submerged macrophytes in sheltered microhabitats. Together, these factors dictate community structure, with water physicochemical properties acting as the central driver of submerged macrophyte dynamics.

4.3 Management applications

In recent decades, considerable efforts have been devoted worldwide to wetland restoration (Bertassello et al., 2025; Jiang et al., 2024). In the long term, the successful restoration of wetlands critically depends on the stable recovery of submerged macrophyte communities, which serve as the ecological foundation of these systems (Rybak et al., 2024). At the catchment scale, geological background determines the fundamental hydrochemical characteristics, exerting an initial environmental filter on submerged macrophyte species by providing different DIC forms (Iversen et al., 2019). At the local scale, massive nutrient inputs from anthropogenic activities, combined with external disturbances, create complex and overlapping effects on submerged macrophyte biomass and spatial distribution (Ibáñez and Peñuelas, 2019). Therefore, effective restoration strategies must integrate both geological context and trophic state to guide the rehabilitation of submerged vegetation in aquatic ecosystems. Although hydrological management approaches have been proposed to maintain water supply and ecological function in the Momoge wetland (Cui et al., 2016), our findings indicate that maintaining hydrological regimes alone is insufficient to prevent further degradation of this fragile ecosystem. This is especially true for submerged macrophyte communities, which function as cornerstone species in aquatic ecosystem restoration (Jeppesen et al., 2012). Here, we advocate a species configuration and pilot selection strategy as a pivotal approach for restoring submerged macrophytes in the Songnen Plain. Given the region’s alkaline water environment, submerged macrophytes should possess the ability to utilize HCO3- for photosynthesis, as this trait enables them to colonize a wide range of habitats and persist under challenging conditions (Hussner et al., 2016; Maberly et al., 2015). The recovery process of submerged vegetation is gradual, involving a series of ecological shifts rather than a sudden reversal (Sand-Jensen et al., 2000; Sayer et al., 2010). Based on the relationships between submerged macrophytes and water column variables, species selection should align with the prevailing trophic status and water transparency. Pioneering species such as P. pectinatus, N. marina, and Char. spiralis should be introduced first in regions with poor water quality and low transparency, where their tolerance to eutrophication allows them to establish initial submerged macrophyte communities. As water quality improves, indigenous dominant species such as U. aurea and C. demersum should be gradually introduced to stabilize and consolidate restoration outcomes. Finally, incorporating ornamental species like M. spicatum into restored patches can enhance biodiversity and ecological stability, supporting long-term resilience. This aligns with the findings of Liu et al. (2020), who demonstrated that the presence of three or more submerged macrophyte species significantly improves water clarity in eutrophic lakes. In addition to species selection, external environmental pressures, particularly wind-induced turbulence and water table fluctuations, should be minimized during the initial stages of restoration (Dudgeon et al., 2006; Reid et al., 2019). Our field observations show that submerged macrophyte biomass is highest in sheltered bay areas and lowest in open water zones, suggesting that restoration areas should be located in relatively stagnant regions with stable water levels. To achieve these conditions, eco-engineering measures such as constructing buffer zones with native emergent aquatic plants (e.g., Phragmites australis and Scirpus planiculmis) are recommended (Pan et al., 2006). These vegetative barriers can attenuate wind and wave energy, creating a more stable microenvironment that facilitates the establishment and persistence of submerged macrophyte communities.

5 Conclusion

In the Songnen Plain wetlands, water salinity and alkalinity are primarily governed by geological processes, particularly rock weathering and evaporation–crystallization. These natural controls set the baseline hydrochemical conditions, while nutrient enrichment from anthropogenic activities and external disturbances, such as wind-induced turbulence and water level fluctuations, impose further modifications on the water column. This combination of natural and human-driven factors has led to profound changes in wetland ecological dynamics. A total of eight submerged macrophyte species representing six families were identified in this study. Among them, M. spicatum, C. demersum, P. pectinatus, P. crispus, and N. marina possess the ability to utilize HCO3-, the predominant DIC form in this alkaline environment. This physiological trait provides these species with a competitive advantage, enabling them to persist and dominate under conditions where CO2 is limited. In contrast, U. aurea, which cannot utilize HCO3-, relies on alternative nutritional strategies, such as zooplankton capture, to survive. The biomass distribution patterns of submerged macrophytes are strongly shaped by water quality gradients. P. pectinatus, N. marina, and Char. spiralis exhibit high biomass in nutrient-rich, low-transparency waters, reflecting their tolerance to eutrophication. Conversely, U. aurea and C. demersum show a strong preference for clearer waters with high transparency, indicating their sensitivity to environmental degradation. Thus, the inorganic carbon regime, nutrient loading, and external physical disturbances collectively act as environmental filters, determining both species assemblages and biomass distributions within submerged macrophyte communities.

From a restoration perspective, our findings emphasize that hydrological management alone is insufficient to reverse wetland degradation. We advocate a hybrid restoration strategy that integrates species configuration and pilot selection to accelerate the recovery of submerged vegetation and associated ecosystem functions. In heavily degraded areas with poor water quality, pioneering species such as P. pectinatus, N. marina, and Char. spiralis should be introduced first to establish a foundational plant community. As water quality improves, sensitive indigenous species like U. aurea and C. demersum can be gradually incorporated to stabilize and diversify the community. Finally, ornamental and structurally complex species such as M. spicatum should be added to enhance biodiversity, ecological resilience, and long-term stability. Moreover, external environmental pressures, particularly wind and wave disturbances, should be mitigated during the initial stages of restoration. Creating sheltered microhabitats by constructing vegetative barriers using native emergent plants, such as Phragmites australis and Scirpus planiculmis, will help buffer wave energy and promote the establishment of submerged macrophytes. In summary, the sustainable restoration of Songnen Plain wetlands requires a comprehensive approach that addresses both geological constraints and human-induced stressors. By integrating species-specific functional traits, nutrient management, and physical habitat modifications, it is possible to restore submerged macrophyte communities, enhance biodiversity, and rebuild the ecological integrity of these fragile wetland ecosystems.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

PW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YL: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. LW: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. RL: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. EX: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZW: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42172285 and No. 41807205), Guangxi Key Research and Development Program (No. GuikeAB24010154 and No. GuikeAB25069497), and National Key Research and Development Project (No. 2016YFC0500403).

Acknowledgments

We would also like to thank the reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1716202/full#supplementary-material

References

Agami, M., Beer., S., and Waisel, Y. (1980). Growth and photosynthsis of Najas marina L. affected by light intensity. Aquat. Bot. 9, 285–289. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(80)90028-5

Bandh, S. A., Shafi, S., Peerzada, M., Rehman, T., Bashir, S., Wani, S. A., et al. (2021). Multidimensional analysis of global climate change: a review. Environ. Sci. pollut. Res. 28, 24872–24888. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-13139-7

Barboza, F. R., Kotta, J., Weinberger, F., Jormalainen, V., Kraufvelin, P., Molis, M., et al. (2019). Geographic variation in fitness-related traits of the bladderwrack Fucus vesiculosus along the Baltic Sea-North Sea salinity gradient. Ecol. Evol. 9, 9225–9238. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5470

Berde, V. B., Chari, P. V. B., and Berde, C. V. (2022). “Wetland and biodiversity hotspot conservation,” in In Research anthology on ecosystem conservation and preserving biodiversity (Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global Scientific Publishing), 775–778.

Bertassello, L. E., Basu, N. B., Maes, J., Grizzetti, B., La Notte, A., and Feyen, L. (2025). The important role of wetland conservation and restoration in nitrogen removal across European river basins. Nat. Water 3, 867–880. doi: 10.1038/s44221-025-00465-0

Blowes, S. A., Supp, S. R., Antão, L. H., Bates, A., Bruelheide, H., Chase, J. M., et al. (2019). The geography of biodiversity change in marine and terrestrial assemblages. Science 366, 339–345. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw1620

Bomfim, F. F., Carvalho, L. S., Sampaio, F. B., Juen, L., Dias-Silva, K., Casatti, L., et al. (2025). Beta diversity of macrophyte life forms: Responses to local, spatial, and land use variables in Amazon aquatic environments. Sci. Total Environ. 958, 178041. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.178041

Bornette, G. and Puijalon, S. (2011). Response of aquatic plants to abiotic factors: a review. Aquat. Sci. 73, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00027-010-0162-7

Carlson, R. E. (1977). A trophic state index for lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 22, 361–369. doi: 10.4319/lo.1977.22.2.0361

Chao, C., Chen, X., Wang, J., and Xie, Y. (2024). Response of submerged macrophytes of different growth forms to multiple sediment remediation measures for hardened sediment. Front. Plant Sci. 15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1450404

Chen, H., Zhang, W., Gao, H., and Nie, N. (2018). Climate change and anthropogenic impacts on wetland and agriculture in the songnen and sanjiang plain, northeast China. Remote Sens. 10, 356. doi: 10.3390/rs10030356

Chen, L., Zhang, G., Xu, Y., Chen, S., Wu, Y., Gao, Z., et al. (2020). Human activities and climate variability affecting inland water surface area in a high latitude river basin. Water 12, 382. doi: 10.3390/w12020382

Cheng, Y. Q. and Zhang, P. Y. (2005). Regional patterns changes of chinese grain production and response of commodity grain base in the northeast China. Geogr. Sci. 21 (5), 513–520. doi: 10.13249/j.cnki.sgs.2005.05.513

China National Environmental Monitoring Centre (2001). Technical specification for the assessment of lake (reservoir) eutrophication and classification (Beijing: State Environmental Protection Administration).

Cui, Z., Shen, H., and Zhang, G. X. (2016). Changes of landscape patterns and hydrological connectivity of wetlands in momoge national natural wetland reserve and their driving factors for three periods. Wetland Sci. 14, 866–873. doi: 10.13248/j.cnki.wetlandsci.2016.06.015

Dar, N. A., Pandit, A. K., and Ganai, B. A. (2014). Factors affecting the distribution patterns of aquatic macrophytes. Limnol. Rev. 14, 75–81. doi: 10.2478/limre-2014-0008

Datta, P. S. and Tyagi, S. K. (1996). Major ion chemistry of groundwater in delhi area: chemical weathering processes and groundwater flow regime. J. Geol. Soc India 47, 179–188. doi: 10.17491/jgsi/1996/470205

Dong, B., Zhou, Y., Jeppesen, E., Qin, B., and Shi, K. (2022). Six decades of field observations reveal how anthropogenic pressure changes the coverage and community of submerged aquatic vegetation in a eutrophic lake. Sci. Total Environ. 842, 156878. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156878

Dudgeon, D., Arthington, A. H., Gessner, M. O., Kawabata, Z., Knowler, D. J., Leveque, C., et al. (2006). Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biol. Rev. 81, 163–182. doi: 10.1017/S1464793105006950

Ferreira, T. F., Crossetti, L. O., Marques, D. M. M., Cardoso, L., Fragoso, C. R., Jr., van Nes, E. H., et al. (2018). The structuring role of submerged macrophytes in a large subtropical shallow lake: clear effects on water chemistry and phytoplankton structure community along a vegetated-pelagic gradient. Limnologica 69, 142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.limno.2017.12.003

Folke, C., Carpenter, S., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Elmqvist, T., Gunderson, L., et al. (2004). Regime shifts, resilience, and biodiversity in ecosystem management. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35, 557–581. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.021103.105711

García Molinos, J., Halpern, B. S., Schoeman, D. S., Brown, C. J., Kiessling, W., Moore, P. J., et al. (2016). Climate velocity and the future global redistribution of marine biodiversity. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 83–88. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2769

Gibbs, R. J. (1970). Mechanisms controlling world water chemistry. Science 170, 1088–1090. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3962.1088

Han, Q., Meng, H., Wang, S., Li, J., Zhang, L., and Feng, L. (2024). Impacts of submerged macrophyte communities on ecological health: A comprehensive assessment in the western waters of Yuanmingyuan Park replenished by reclaimed water. Ecol. Eng. 202, 107220. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2024.107220

Huang, M., Peng, G., Leslie, L. M., Shao, X. M., and Sha, W. Y. (2005). Seasonal and regional temperature changes in China over the 50 year period 1951-2000. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 89, 105–115. doi: 10.1007/s00703-005-0124-0

Hussner, A., Mettler-Altmann, T., Weber, A. P. M., and Sand-Jensen, K. (2016). Acclimation of photosynthesis to supersaturated CO2 in aquatic plant bicarbonate users. Freshw. Biol. 61, 1720–1732. doi: 10.1111/fwb.12812

Ibáñez, C. and Peñuelas, J. (2019). Changing nutrients, changing rivers. Science 365, 637–638. doi: 10.1126/science.aay2723

Iversen, L. L., Winkel, A., Baastrup-Spohr, L., Hinke, A. B., Alahuhta, J., Baattrup-Pedersen, A., et al. (2019). Catchment properties and the photosynthetic trait composition of freshwater plant communities. Science 366, 878–881. doi: 10.1126/science.aay594

Jeppesen, E., Søndergaard, M., Søndergaard, M., and Christoffersen, K. (2012). The structuring role of submerged macrophytes in lakes (New York: Springer).

Jiang, M., Lu, X. G., Xu, L. S., Chu, L. J., and Tong, S. Z. (2007). Flood mitigation benefit of wetland soil-A case study in Momoge National Nature Reserve in China. Ecol. Econ. 61, 217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.10.019

Jiang, H. B., Wen, Y., Zou, L. F., Wang, Z. Q., He, C. G., and Zou, C. L. (2016). The effects of a wetland restoration project on the Siberian crane (Grus leucogeranus) population and stopover habitat in Momoge National Nature Reserve, China. Ecol. Eng. 96, 170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.01.016

Jiang, W., Zhang, Z., Ling, Z., and Deng, Y. (2024). Experience and future research trends of wetland protection and restoration in China. J. Geog. Sci. 34, 229–251. doi: 10.1007/s11442-024-2203-5

Klee, R. J., Zimmerman, K. I., and Daneshgar, P. P. (2019). Community succession after cranberry bog abandonment in the new Jersey pinelands. Wetlands 39, 777–788. doi: 10.1007/s13157-019-01129-y

Kou, Y. Q. (2012). Purification of farmland back water in Jilin western salinized wetland-A case of Momoge National Nature Reserve. PhD Thesis (Changchun: Northeast Normal Univrrsity).

Kumar, S. K., Rammohan, V., Sahayam, J. D., and Jeevanandam, M. (2009). Assessment of groundwater quality and hydrogeochemistry of Manimuktha River basin, Tamil Nadu, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 159, 341. doi: 10.1007/s10661-008-0633-7

Kumar, S., Singh, R., Kumar, D., Bauddh, K., Kumar, N., and Kumar, R. (2023). “An introduction to the functions and ecosystem services associated with aquatic macrophytes,” in In aquatic macrophytes: ecology, functions and services (Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore), 1–20.

Lakshmanan, E., Kannan, R., and Kumar, M. S. (2003). Major ion chemistry and identification of hydrogeochemical processes of ground water in a part of Kancheepuram district, Tamil Nadu, India. Environ. Geosci. 10, 157–166. doi: 10.1306/eg.0820303011

Lehmann, N., Lantuit, H., Böttcher, M. E., Hartmann, J., Eulenburg, A., and Thomas, H. (2023). Alkalinity generation from carbonate weathering in a silicate-dominated headwater catchment at Iskorasfjellet, northern Norway. Biogeosciences 20, 3459–3479. doi: 10.5194/bg-20-3459-2023

Li, R., Dong, M., Zhao, Y., Zhang, L., Cui, Q., and He, W. M. (2007). Assessment of water quality and identification of pollution sources of plateau lakes in yunnan (China). J. Environ. Qual. 36, 291–297. doi: 10.2134/jeq2006.0165

Li, F., Zhang, S., Yang, J., Chang, L., Yang, H., and Bu, K. (2018). Effects of land use change on ecosystem services value in West Jilin since the reform and opening of China. Ecosyst. Serv. 31, 12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.03.009

Lind, L., Eckstein, R. L., and Relyea, R. A. (2022). Direct and indirect effects of climate change on distribution and community composition of macrophytes in lentic systems. Biol. Rev. 97, 1677–1690. doi: 10.1111/brv.12858

Liu, H., Zhou, W., Li, X. W., Chu, Q. S., Tang, N., Shu, B. Z., et al. (2020). How many submerged macrophyte species are needed to improve water clarity and quality in Yangtze floodplain lakes? Sci. Total Environ. 724, 138267. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138267

Lu, S. B., Zhang, X. L., Wang, J. H., and Pei, L. (2016). Impacts of different media on constructed wetlands for rural household sewage treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 127, 325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.166

Luo, S., Yuan, J., Song, Y., Ren, J., Qi, J., Zhu, M., et al. (2025). Elevated salinity decreases microbial communities complexity and carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus metabolism in the Songnen Plain wetlands of China. Water Res. 276, 123285. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2025.123285

Maberly, S. C. (1996). Diel, episodic and seasonal changes in pH and concentrations of inorganic carbon in a productive lake. Freshw. Biol. 35, 579–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1996.tb01770.x

Maberly, S. C., Berthelot, S. A., Stott, A. W., and Gontero, B. (2015). Adaptation by macrophytes to inorganic carbon down a river with naturally variable concentrations of CO2. J. Plant Physiol. 172, 120–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.07.025

Maberly, S. C. and Gontero, B. (2017). Ecological imperatives for aquatic CO2-concentrating mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 3797–3814. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx201

Mitsch, W. (1993). Ecological engineering A cooperative role with the planetary life-support system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 27, 438–445. doi: 10.1021/es00040a600

Mitsch, W. J., Bernal, B., and Hernandez, M. E. (2015). Ecosystem services of wetlands. Int. J. Bio. Sci. Ecosystem Serv. Manage. 11, 1–4. doi: 10.1080/21513732.2015.1006250

Mitsch, W. J. and Gosselink, J. G. (2000). The value of wetlands: importance of scale and landscape setting. Ecol. Econ. 35, 25–33. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00165-8

Moi, D. A., Lansac-Tôha, F. M., Romero, G. Q., Sobral-Souza, T., Cardinale, B. J., and Kratina, P. (2024). Human pressure drives biodiversity-multifunctionality relationships in large Neotropical wetlands. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 1279–1289. doi: 10.1038/s41559-022-01827-7

Nosetto, M. D., Jobbágy, E. G., Tóth, T., and Jackson, R. B. (2008). Regional patterns and controls of ecosystem salinization with grassland afforestation along a rainfall gradient. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 22, GB2015. doi: 10.1029/2007GB003000

Pan, X. L., Zhang, D. Y., and Quan, L. (2006). Interactive factors leading to dying-off Carex tato in Momoge wetland polluted by crude oil, Western Jilin, China. Chemosphere 65, 1772–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.04.063

Puche, E., Cruz, D., Delgado, P., Rosińska, J., and Rodrigo, M. A. (2024). Changes in submerged macrophyte diversity, coverage and biomass in a biosphere reserve site after 20 years: A plea for conservation efforts. Biol. Conserv. 294, 110607. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110607

Reid, A. J., Carlson, A. K., Creed, I. F., Eliason, E. J., Gell, P. A., Johnson, P. T. J., et al. (2019). Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biol. Rev. 94, 849–873. doi: 10.1111/brv.12480

Richardson, A. D., Duigan, S. P., and Berlyn, G. P. (2002). An evaluation of noninvasive methods to estimate foliar chlorophyll content. New Phytol. 153, 185–194. doi: 10.1046/j.0028-646X.2001.00289.x

Rodrigo, M. A. (2021). Wetland restoration with hydrophytes: A review. Plants 10, 1035. doi: 10.3390/plants10061035

Rutishauser, R. (1993). The developmental plasticity of Utricularia aurea (Lentibulariaceae) and its floats. Aquat. Bot. 45, 119–143. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(93)90018-R

Rybak, M., Rosińska, J., Wejnerowski, Ł., Rodrigo, M. A., and Joniak, T. (2024). Submerged macrophyte self-recovery potential behind restoration treatments: sources of failure. Front. Plant Sci. 15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1421448

Sand-Jensen, K. and Pedersen, O. (1999). Velocity gradients and turbulence around macrophyte stands in streams. Freshw. Biol. 42, 315–328. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2427.1999.444495.x

Sand-Jensen, K., Riis, T., Vestergaard, O., and Larsen, S. E. (2000). Macrophyte decline in Danish lakes and streams over the past 100 years. J. Ecol. 88, 1030–1040. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2000.00519.x

Sayer, C. D., Burgess, A., Kari, K., Davidson, T. A., Peglar, S., Yang, H. D., et al. (2010). Long-term dynamics of submerged macrophytes and algae in a small and shallow, eutrophic lake: implications for the stability of macrophyte-dominance. Freshw. Biol. 55, 565–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2009.02353.x

Sharma, L. K. and Naik, R. (2024). “Wetland ecosystems,” in In Conservation of saline wetland ecosystems: an initiative towards UN decade of ecological restoration (Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore), 3–32.

Søndergaard, M., Davidson, T. A., Lauridsen, T. L., Johansson, L. S., and Jeppesen, E. (2022). Submerged macrophytes in Danish lakes: impact of morphological and chemical factors on abundance and species richness. Hydrobiologia 849, 3789–3800. doi: 10.1007/s10750-021-04759-8

Søndergaard, M., Johansson, L. S., Lauridsen, T. L., Jørgensen, T. B., Liboriussen, L., and Jeppesen, E. (2010). Submerged macrophytes as indicators of the ecological quality of lakes. Freshw. Biol. 55, 893–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2009.02331.x

Stevens, C. J. (2019). Nitrogen in the environment. Science 363, 578–580. doi: 10.1126/science.aav8215

Su, H. J., Wu, Y., Xia, W. L., Yang, L., Chen, J. F., Han, W. X., et al. (2019). Stoichiometric mechanisms of regime shifts in freshwater ecosystem. Water Res. 149, 302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.11.024

Szabó, S., Fedor, N., Koleszár, G., Braun, M., Korponai, J., Kočić, A., et al. (2025). Submerged macrophytes can maintain stable dominance over free-floating competitors through high pH. Freshw. Biol. 70, e14363. doi: 10.1111/fwb.14363

Szoszkiewicz, K., Pietruczuk, K., Jusik, S., Budka, A., and Pietruczuk, K. (2025). Richness of macrophyte functional groups in relation to hydromorphological and hydrochemical factors of organic rivers in the Biebrza National Park. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol, 100667. doi: 10.1016/j.ecohyd.2025.100667

Tobiessen, P. and Snow, P. D. (1984). Temperature and light effects on the growth of Potamogeton crispus in Collins Lake, New York State. Canad. J. Bot. 62, 2822–2826. doi: 10.1139/b84-376

Volik, O., Petrone, R., and Price, J. (2023). Wetlands as integral parts of surface water–groundwater interactions in the Athabasca Oil Sands Area: Review and synthesis. Environ. Rev. 32, 145–172. doi: 10.1139/er-2023-0064

Wang, P., Bai, B., Cao, J., and Wu, Z. (2024). Experimental insights into the stability of karst carbon sink by submerged macrophytes. Environ. Earth Sci. 83, 422. doi: 10.1007/s12665-024-11697-w

Wang, X. Y., Feng, J., and Zhao, J. M. (2010). Effects of crude oil residuals on soil chemical properties in oil sites, Momoge Wetland, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 161, 271–280. doi: 10.1007/s10661-008-0744-1

Wang, P., Hu, Q. J., Wang, P. H., Li, B., and Cao, J. H. (2015). Effect of karst geology on the submerged macrophyte community in Zhaidi River, Guilin. J. Hydroecol. 36, 34–39. doi: 10.15928/j.1674-3075.2015.01.005

Wang, Z. C., Li, Q. S., Li, X. J., Song, C. C., and Zhang, G. X. (2003). Sustainable agriculture development in saline-alkali soil area of Songnen Plain, Northeast China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 13, 171–174. doi: 10.1007/s11769-003-0012-9

Wang, L., Seki, K., Miyazaki, T., and Ishihama, Y. (2009). The causes of soil alkalinization in the Songnen Plain of Northeast China. Paddy Water Environ. 7, 259–270. doi: 10.1007/s10333-009-0166-x

Wang, P., Hu, G., and Cao, J. H. (2017). Stable carbon isotopic composition of submerged plants living in karst water and its eco-environmental importance. Aquat. Bot. 140, 78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2017.03.002

Wang, P., Zhang, X., Wang, D., Wu, Z., and Cao, J. (2020). Experimental study on growth of Hydrilla verticillata under different concentrations of bicarbonate and its implication in karst aquatic ecosystem. Carbonate. Evaporite. 35, 83. doi: 10.1007/s13146-020-00618-0

Wei, J., Gao, J., Wang, N., Liu, Y., Wang, Y. W., Bai, Z. H., et al. (2019). Differences in soil microbial response to anthropogenic disturbances in Sanjiang and Momoge Wetlands, China. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 95, fiz110. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiz110

Xia, W., Zhu, B., Zhang, S., Liu, H., Qu, X., Liu, Y. L., et al. (2022). Climate, hydrology, and human disturbance drive long-term, (1988––2018) macrophyte patterns in water diversion lakes. J. Environ. Manage. 319115726. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115726

Xiao, J., Jin, Z. D., Wang, J., and Zhang, F. (2015). Hydrochemical characteristics, controlling factors and solute sources of groundwater within the Tarim River Basin in the extreme arid region, NW Tibetan Plateau. Quat. Int. 380-381, 237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2015.01.021

Yin, L. Y., Li, W., Madsen, T. V., Maberly, S. C., and Bowes, G. (2017). Photosynthetic inorganic carbon acquisition in 30 freshwater macrophytes. Aquat. Bot. 140, 48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2016.05.002

Zhang, Y., Liu, N., Lei, W., Fu, H., and Liu, Z. (2024). Abrupt shift in the organic matter input to sediments in Lake Liangzi, a typical macrophyte-dominated shallow lake in Eastern China, and its response to anthropogenic impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 947, 174668. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174668

Zhang, C., Pei, H., Lu, C., Liu, P., Liu, C., and Lei, G. (2022). Eutrophication drives regime shift via changes in stoichiometric homeostasis-based submerged macrophyte assemblages. NPJ Clean Water 5, 17. doi: 10.1038/s41545-022-00161-6

Zhang, B., Song, X., Zhang, Y., Han, D., Tang, C., Yang, L., et al. (2015). The relationship between and evolution of surface water and groundwater in Songnen Plain, Northeast China. Environ. Earth Sci. 73, 8333–8343. doi: 10.1007/s12665-014-3995-x

Zhang, T., Wang, P., He, J., Liu, D., Wang, M., Wang, M., et al. (2023). Hydrochemical characteristics, water quality, and evolution of groundwater in Northeast China. Water 15, 2669. doi: 10.3390/w15142669

Keywords: submerged macrophyte, water physicochemical properties, biomass distribution, HCO3- utilization, wetland restoration

Citation: Wang P, Long Y, Wang L, Lu R, Xiao E and Wu Z (2025) Water physicochemical properties shape the distribution of submerged macrophytes: implications for wetland restoration in Songnen Plain. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1716202. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1716202

Received: 30 September 2025; Accepted: 12 November 2025; Revised: 07 November 2025;

Published: 05 December 2025.

Edited by:

Dragana Vukov, University of Novi Sad, SerbiaReviewed by:

Tao Yang, Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaHang Shan, Zhejiang University, China

Copyright © 2025 Wang, Long, Wang, Lu, Xiao and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pei Wang, cHdhbmdAaWhiLmFjLmNu; Enrong Xiao, ZXJ4aWFvQGloYi5hYy5jbg==; Zhenbin Wu, d3V6YkBpaGIuYWMuY24=

Pei Wang

Pei Wang Yinian Long2,3

Yinian Long2,3