- 1Henan Sesame Research Center, Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Zhengzhou, China

- 2The Shennong Laboratory, Zhengzhou, China

- 3Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Flowering time, a critical trait for crop adaptation, is regulated by plants’ ability to sense light signals, which influences gene expression and the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. In this study, five populations of sesame (Sesamum indicum) were developed by crossing ‘Yuzhi 4’ with ‘BS377’ (late-flowering variety). Linkage mapping analysis revealed that a ~400 kb region on chromosome 11 had the most significant and stable effect on flowering time. FLOWERING LOCUS T-like (FTL) and HEADING DATE 3A (Hd3a), located within the candidate region, are associated with flowering time as revealed by RNA-seq and qRT-PCR analyses. Integrated analyses of SiFTL gene structure and transcript level revealed that the absence of SiFTL expression leads to the late-flowering phenotype in BS377. Moreover, SiFTL and SiHd3a, which are highly homologous to Arabidopsis FT and TWIN SISTER OF FT (TSF), are associated with earlier flowering. Furthermore, the Yuzhi 4 haplotypes of SiFTL and SiHd3a locus co-segregated with the early-flowering trait in a recombinant inbred line (RIL) population. In addition, heterologous expression of the Yuzhi 4 haplotypes of SiFTL and SiHd3a significantly accelerated flowering in Arabidopsis Col-0 and the ft-10 mutant under both long-day (LD) and short-day (SD) conditions. These haplotypes may function as universal floral activators downstream of flowering pathways. These findings not only enhance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms controlling flowering time in sesame but also offer valuable genetic resources for breeding early-maturing varieties.

Introduction

Flowering marks the transition from vegetative growth to reproductive development in plants, reflecting their adaptation to local seasonal and environmental conditions (Kloosterman et al., 2012). Flowering time impacts biomass and yield in many crops, making it a key target for crop breeding (Schiessl et al., 2014; Ortega et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). In Arabidopsis, flowering time is regulated by multiple interconnected genetic pathways, including the photoperiod, autonomous, vernalization, gibberellic acid, and ambient temperature pathways (Jin et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2024). FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) a central component of these pathways, integrates signals from various pathways to promote flowering (Lifschitz et al., 2006; Song et al., 2013; Mäckelmann et al., 2024). The FT protein, a member of the phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein (PEBP) family, is highly conserved across plant species and plays critical roles in growth and differentiation signaling pathways (Lifschitz et al., 2006). In Arabidopsis, the PEBP gene family is divided into three main subfamilies: FT-like, TERMINAL FLOWER1 (TFL1)-like, and MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 (MFT)-like (Chardon and Damerval, 2005). The FT-like clade comprises FT and TWIN SISTER OF FT (TSF), which act as potent floral activators (Jin et al., 2015).The TFL1-like subfamily consists of TFL1, ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA CENTRORADIALIS (ATC), and BROTHER OF FT AND TFL1 (BFT), are key repressors that modulate flowering time and inflorescence architecture (Chardon and Damerval, 2005). The MFT-like subfamily contains only MFT, which functions in seed development and germination during both gametophyte and sporophyte stages (Dong et al., 2020).

In various plants, such as Arabidopsis and rice, the FT protein is primarily synthesized in the leaves (specifically in phloem companion cells) and transported through the phloem to the nuclei of shoot apical meristem cells (Neumaier and James, 1993; Tamaki et al., 2007). There, it physically interacts with 14-3–3 proteins and the basic leucine zipper transcription factor FLOWERING LOCUS D (FD) to form the florigen activation complex (Corbesier et al., 2007; Taoka et al., 2011). This complex directly binds to the promoters of floral meristem identity genes, such as LEAFY and APETALA1, activating their expression to initiate floral differentiation (Kobayashi et al., 2012). Heterologous expression of FT orthologs from various plant species has been shown to induce flowering, demonstrating the highly conserved function of FT across both dicots and monocots, including rice, wheat, Arabidopsis, tomato, soybean, Populus, and others (Kojima et al., 2002; Lifschitz et al., 2006; Corbesier et al., 2007; Komiya et al., 2008; Kong et al., 2010; Hsu et al., 2011; Rinne et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2020; Gu et al., 2022). Although the genetic basis of flowering time has been extensively studied in model plants, the genetic regulators of this trait in sesame, particularly the roles of flowering time gene, have not been fully elucidated.

Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.), a member of the Pedaliaceae family, is a significant oilseed crop renowned for its edible seeds and high-quality oil. It is widely cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide (Miao et al., 2021). Sesame is a short-day (SD) plant, typically delaying flowering and extending its vegetative growth phase under long-day (LD) conditions, resulting in late maturity (Suddihiyam et al., 1992; Zhou et al., 2018). Conversely, under SD conditions, sesame flowers earlier and completes its life cycle more quickly (Rhind, 1935; Ghosh, 1955). Flowering time is a critical trait that significantly impacts sesame yield and adaptation (Sinha et al., 1973; Kumazaki et al., 2008, 2009; Miao et al., 2021; Sabag et al., 2024). Phylogenetic analysis of CONSTANS-like (COL) genes suggests that SiCOL1 likely plays a role in regulating flowering in sesame, and natural variations in SiCOL1 may be associated with the expansion of sesame cultivation to high-latitude regions (Zhou et al., 2018). Expression profiles of FT and circadian clock-associated genes in early- and late-flowering sesame varieties indicate that SiCOLs or their regulators may be the causal genes influencing flowering time variation (López et al., 2023). Additionally, a key single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) site (C allele) is found in the FLOWERING LOCUS T-like (FTL) gene, which significantly shortens flowering time under suitable sowing conditions (Sabag et al., 2024). However, there is limited information available on how genes regulate flowering time in sesame.

To uncover the molecular mechanisms controlling flowering in sesame, we selected two sesame germplasms: Yuzhi 4, a high agronomic performance and broad adaptability, and BS377, a late-flowering variety with small seed size and high lignan content, which exhibits prolonged vegetative growth. We crossed these two varieties and recorded flowering time across five generations (BC1, BC1F2, F2, F2:3, and recombinant inbred line (RIL) progenies). Using linkage mapping and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), we identified potential flowering time regulators, pinpointing candidate genes SiFTL and HEADING DATE 3A (Hd3a) within a ~400 kb region on chromosome 11 associated with flowering time. Our findings provide insights into genetic mechanisms controlling flowering time in sesame, offering a foundation for future germplasm improvement strategies to optimize early maturation and environmental adaptability.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The seeds of Yuzhi 4 and BS377 sesame varieties were obtained from the sesame germplasm repository at the Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Zhengzhou, Henan Province, China. Yuzhi 4 is an elite cultivar released in the 1980s and has been widely cultivated in most sesame-growing regions in China over the past three decades due to its high agronomic performance and broad adaptability. BS377, an unnamed cultivar introduced from Bangladesh, exhibits a long vegetative growth period or even fails to flower under natural conditions in temperate regions due to its photoperiod sensitivity. Two populations, F2 and BC1, were developed from a cross between Yuzhi 4 (as the maternal and recurrent parent) and BS377 (as the paternal parent). These populations were self-pollinated to produce F2:3 and BC1F2 families, respectively (Figure 1). Phenotypic data were collected in Sanya (N18°14’, E109°29’; hereafter SY), Pingyu (N32°59’, E114°42’; hereafter PY), Nanyang (N32°54’, E112°24’; hereafter NY), and Luohe (N33°37’, E113°58’; hereafter LH). The day length in the summer (from 5–7 th May to 22–24 th July) of PY, NY and LH, ranged from 13.6 h to 14.3 h, whereas in the winter (from 7–8 th November to 20–21 th January) in SY, daylight was sustained for from 11.0 h to 11.3 h.

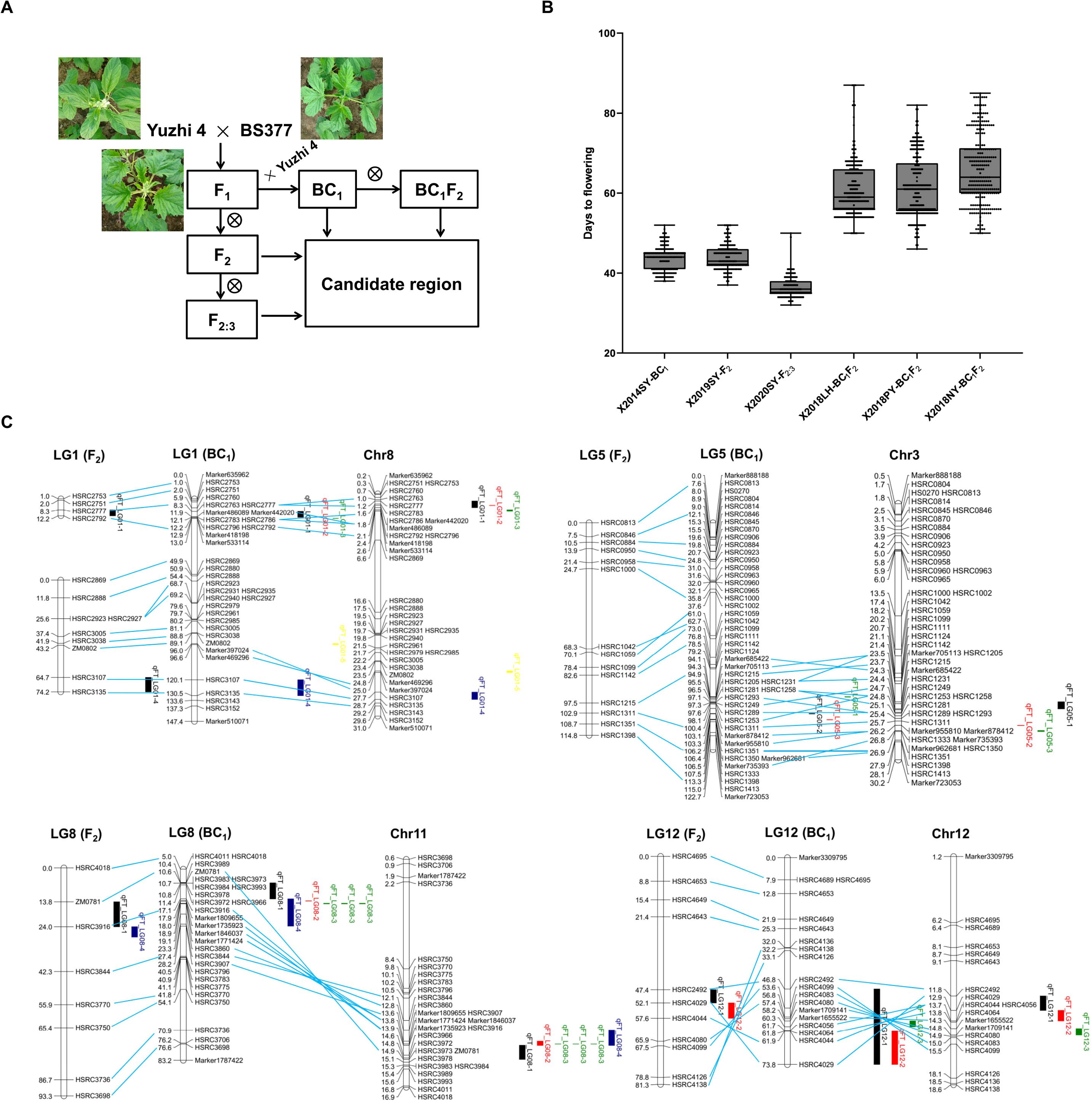

Figure 1. QTL mapping of flowering time in sesame. (A) Segregating populations generated by crossing the photoperiod-insensitive variety Yuzhi 4 with the photoperiod-sensitive variety BS377. Backcrossing used Yuzhi 4. (B) Flowering time of four populations in different environments. SY, LH, PY and NY represent Sanya, Luohe, Pingyu, and Nanyang. (C) QTL of flowering time identified in different populations.

Plant samples and treatments

The two parents and ~ 150 plants were randomly selected from the F2 and BC1 populations for genotyping and linkage map construction. For phenotypic data collection in field trials, 150 BC1 and 146 F2 individuals, as well as 128 F2:3 and 150 BC1F2 families, were utilized. The BC1F2 families, each with two replicates, were planted in LH, PY and NY. Flowering time was measured as the number of days from sowing to when 60% of the plants were flowering (approximately 7 out of 12 individual plants). The determination of flowering date was based on the opening of the first flower on a single plant of BC1 and F2, and the opening of the first flower on more than 60% of the plants of BC1F2, F2:3 and RIL populations (Supplementary Table S1).

Leaves from the Yuzhi 4 variety were collected at eight developmental stages (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, and S8), corresponding to 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 days (d) after sowing (Figure 2; Supplementary Figure 1). Leaves of the late-flowering BS377 variety were collected at the corresponding developmental stages as Yuzhi 4, specifically at 5, 15, 35, 60, 65, 70, 75, and 90 d after sowing. S6 and S7 indicate the pre-budding and post-budding stages, respectively, while S8 denotes the post-flowering stage. Sampling was conducted at 9:00 am in a controlled phytotron under a 12 h light (8:00 to 20:00) and 12 h dark cycle. Samples from each stage were ground into powder using liquid nitrogen and stored at - 80 °C for subsequent experiments.

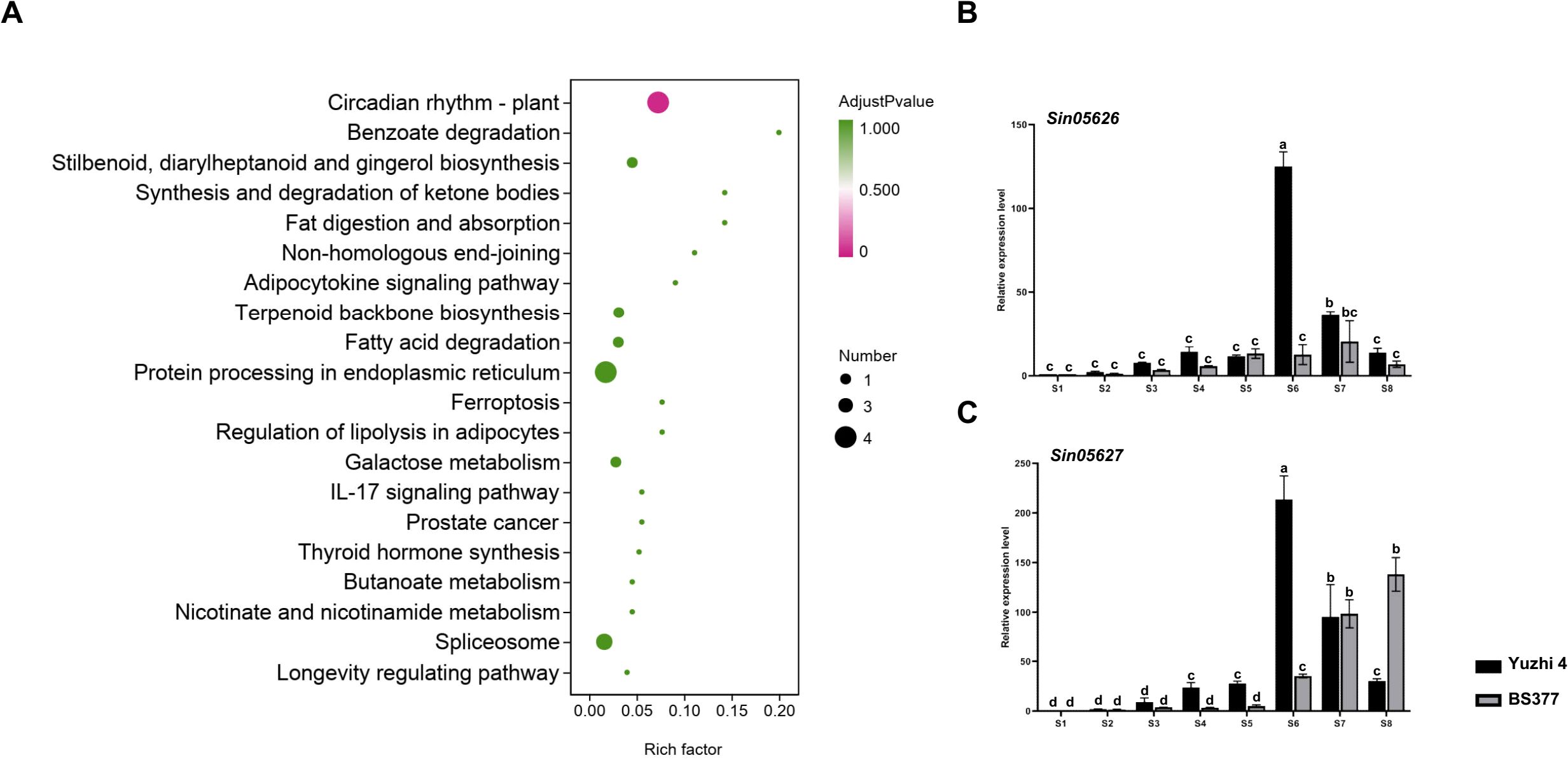

Figure 2. The DEGs in candidate region revealed by RNA-seq and qRT-PCR. (A) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for genes in the candidate regions based on RNA-seq data. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of Sin05626 during eight developmental stages of Yuzhi 4 and BS377 new leaves. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of Sin05627 during eight developmental stages of Yuzhi 4 and BS377 new leaves. S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8 represent the leaves of the Yuzhi 4 variety at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35 and 40 days after sowing. S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8 represent the leaves of the BS377 variety at 5, 15, 35, 60, 65, 70, 75, and 90 d after sowing. S6 and S7 indicate the pre-budding and post-budding stages, respectively, while S8 denotes the post-flowering stage. Different letters indicate the statistical difference among samples at P ≤ 0.05 according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

Linkage map construction and quantitative trait loci mapping

In a previously study, we constructed a genetic map with 351 SSRs and 3,548 specific-locus amplified fragments (SLAFs) for the BC1 population (Mei et al., 2023; Supplementary Table S2). The F2 population was genotyped using a subset of 166 SSR markers, including 152 markers evenly distributed across the BC1-derived genetic map and 14 dominant markers (containing Yuzhi 4 alleles) excluded from the BC1 analyses (Mei et al., 2023; Supplementary Table S2). The genetic map was constructed using JoinMap 4.0. QTL mapping was performed using the IciMapping 4.1 software (Meng et al., 2015) with the inclusive composite interval mapping additive (ICIM-ADD) model (Li et al., 2007), and the significant LOD threshold was determined by 1,000 permutations (P = 0.05). Phenotypic variation explained (PVE) by each QTL was calculated based on variance contribution. Genetic maps and QTLs were visualized using MapChart 2.3 (Voorrips, 2002).

Expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from eight developmental stages of Yuzhi 4 and BS377 using an EZNA Plant RNA Kit (R6827-01, Omega Biotek, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was used for library construction and subjected to deep sequencing on an Illumina novaseq 6000 (Kindstar Sequenon Biotechnology (Wuhan) Co., LTD). Raw paired-end sequencing reads were quality controlled and filtered using fastp (version 0.23.4) (Chen et al., 2018). Reads shorter than 15 base pairs were removed, and bases with a Phred quality score below 20 were trimmed. The high-quality clean reads data were aligned to the sesame reference genome Yuzhi 4, and gene expression levels were quantified using transcripts per million (TPM). Gene annotations were performed by aligning BLAST search results to multiple databases, including Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), COG/KOG, Pfam, NCBI non-redundant protein sequences (Nr), and the manually curated UniProt Knowledgebase, providing functional information for gene characterization. The RNA-seq data are available from BIG Submission (GSA accession: CRA032111). The candidate genes within the region were functionally annotated using KEGG and GO analyses, and their expression levels were quantified using TPM analysis.

To validate the RNA-seq data, approximately 1.5 mg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the MightyScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Master Mix (Sangon biotech, China). The quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) primers were designed using Vector NTI, avoiding conserved regions, with amplicon lengths ranging from 120–160 bp (Supplementary Table S3). The qRT-PCR reactions were performed using Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Nanjing, China) with the following parameters on the LightCycler480 system. The relative gene expression levels were determined using the comparative 2-ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001; Figure 2). Gene expression levels were normalized using the sesame housekeeping gene SiTUB (Wei et al., 2013). All experiments were performed in triplicate using biological replicates.

Gene structure and phylogenetic analysis

The genomes of Yuzhi 4 and BS377 were aligned using SyRI software, although their genome sequences have not yet been released (Figure 3; Supplementary Figure 2). For homologous gene identification, the Arabidopsis PEBP amino acid sequences from TAIR (The Arabidopsis Information Resource) were used as queries to search the NCBI non-redundant protein database (nr) using BLAST-P (Altschul et al., 1990), and removed redundant genes from the same clade (100% similarity). Following sequence and conserved domain validation, full-length PEBP amino acid sequences from Oryza sativa, Glycine max, and Sesamum indicum (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_000512975.1/) were used to construct a phylogenetic tree. The tree was generated using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA 5.0, with the p-distance model, complete gap deletion, and 1000 bootstrap replicates (Zhao et al., 2018; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Gene structure and phylogenetic relationship analysis for candidate genes. (A) Gene structure analysis of Sin05626 and Sin05627 comparing the sequences from Yuzhi 4 and BS377 genome. Green rectangle represents exon, white rectangle represents intron, yellow rectangle represents conserved domain, red line represents SNP in the exon. (B) Phylogenetic relationship of PEBP family across various species containing Arabidopsis (blue), rice, soybean, and sesame (red), constructed using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA5 software. Proteins SiFTL and SiHd3a in blue box.

Haplotypes of SiFTL and SiHd3a is associated with flowering time

The RIL population was developed by crossing Yuzhi 4 with BS377 and eight generations of selfing, producing a phenotypically stable population. To evaluate the relationship among annotation indicated that SiFTL, SiHd3a, and flowering time, a RIL population (n = 425) was planted in PY on August 1, 2024, and genomic DNA was extracted for analysis (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S1). Primers were designed based on sequence differences between BS377 and Yuzhi 4 (Figure 4; Supplementary Figure 3; Supplementary Table S3). The SiFTL band presence corresponds to the BS377 haplotype, while the SiHd3a band corresponds to the Yuzhi 4 haplotype (Figures 4A, C). PCR amplification experiments were performed with these primers, and their specific amplification of target fragments was confirmed via electrophoresis.

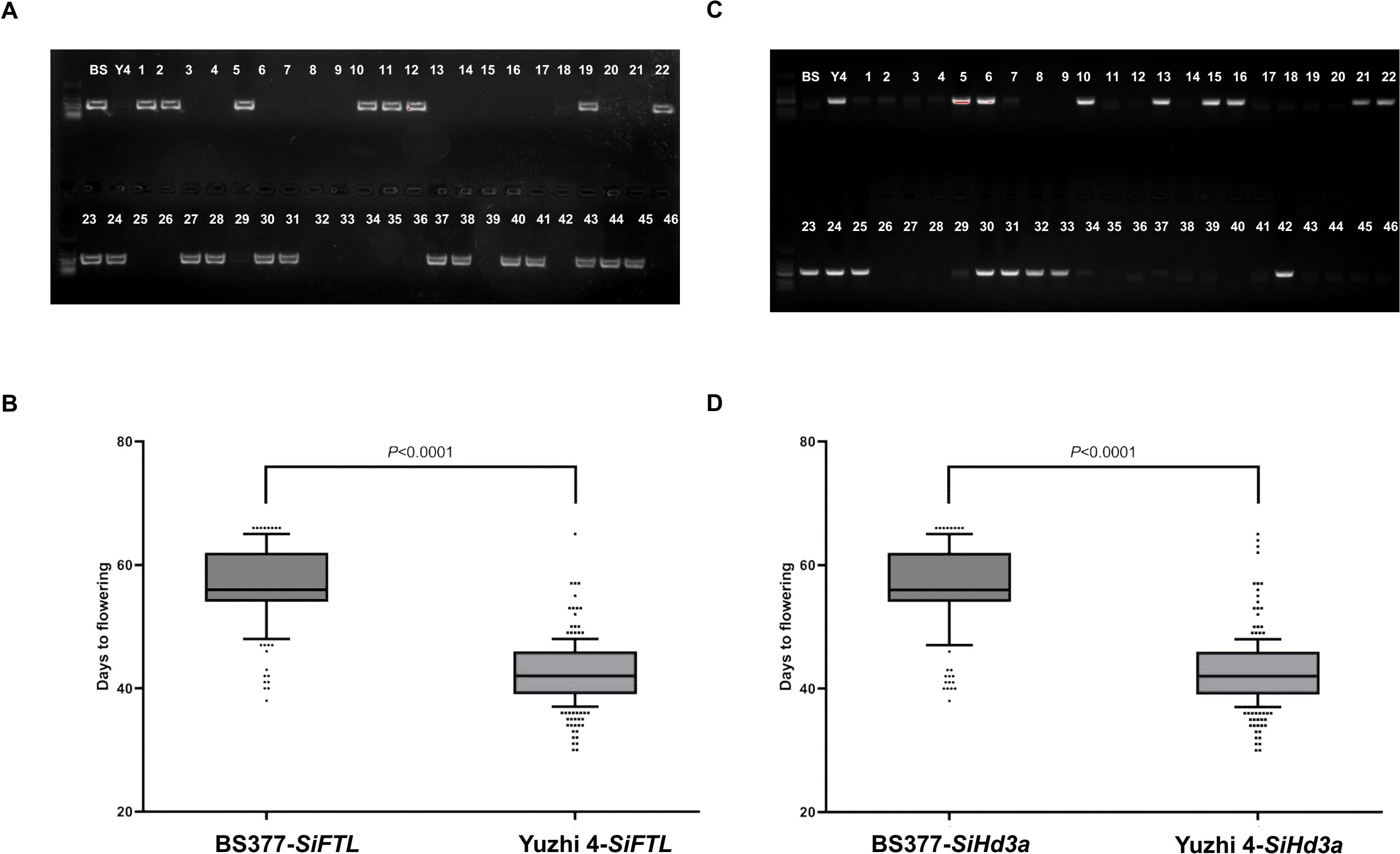

Figure 4. Validation SiFTL and SiHd3a alleles for flowering time under Yuzhi 4 and BS377 backgrounds using a RIL population. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis detected BS377 haplotype of SiFTL in RIL populations. (B) Validation of SiFTL haplotype on chromosome 11 for flowering time. (C) Agarose gel electrophoresis detected Yuzhi 4 haplotype of SiHd3a in RIL populations. (D) Validation of SiHd3a haplotype on chromosome 11 for flowering time. The statistical difference among samples at P ≤ 0.001 according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

Generation of transgenic plants

The full-length coding sequences SiFTL and SiHd3a were amplified from cDNA using primers SiFTL-F/R and SiHd3a-F/R. To generate the recombination vector, SiFTL and SiHd3a were amplified using specific primers and then subcloned into the BamHI site of the C15 vector. The C15 vector was driven by the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (CaMV 35S) and contained a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) epitope tag (Liu et al., 2019). Transgenic lines for SiFTL and SiHd3a were generated according to Agrobacterium-mediated transformation protocols. The seeds of the Col-0 ecotype were maintained in our laboratory, and seeds of the Arabidopsis ft-10 mutant were kindly provided by Associate Researcher Zhang Xiaomei at the Institute of Crop Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Col-0, Arabidopsis ft-10 mutant, and transgenic plants were grown in a growth chamber under LD conditions (16 h light/8 h dark, 22/18°C) (Figures 5, 6) or SD conditions (10 h light/14 hdark, 22/18°C) (Figure 7). We generated T2 transgenic lines and selected 30 representative overexpression (OE) lines for phenotypic analysis.

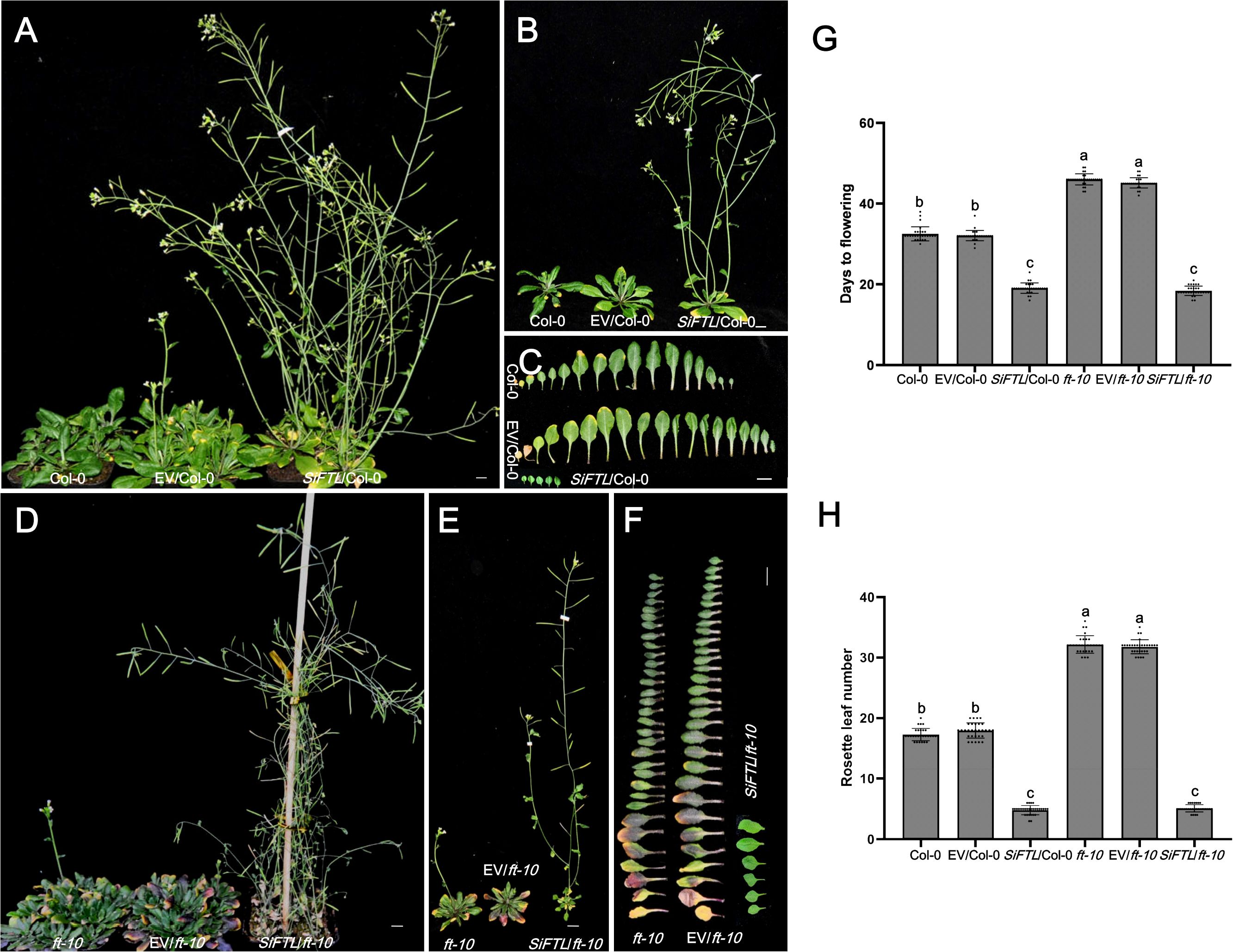

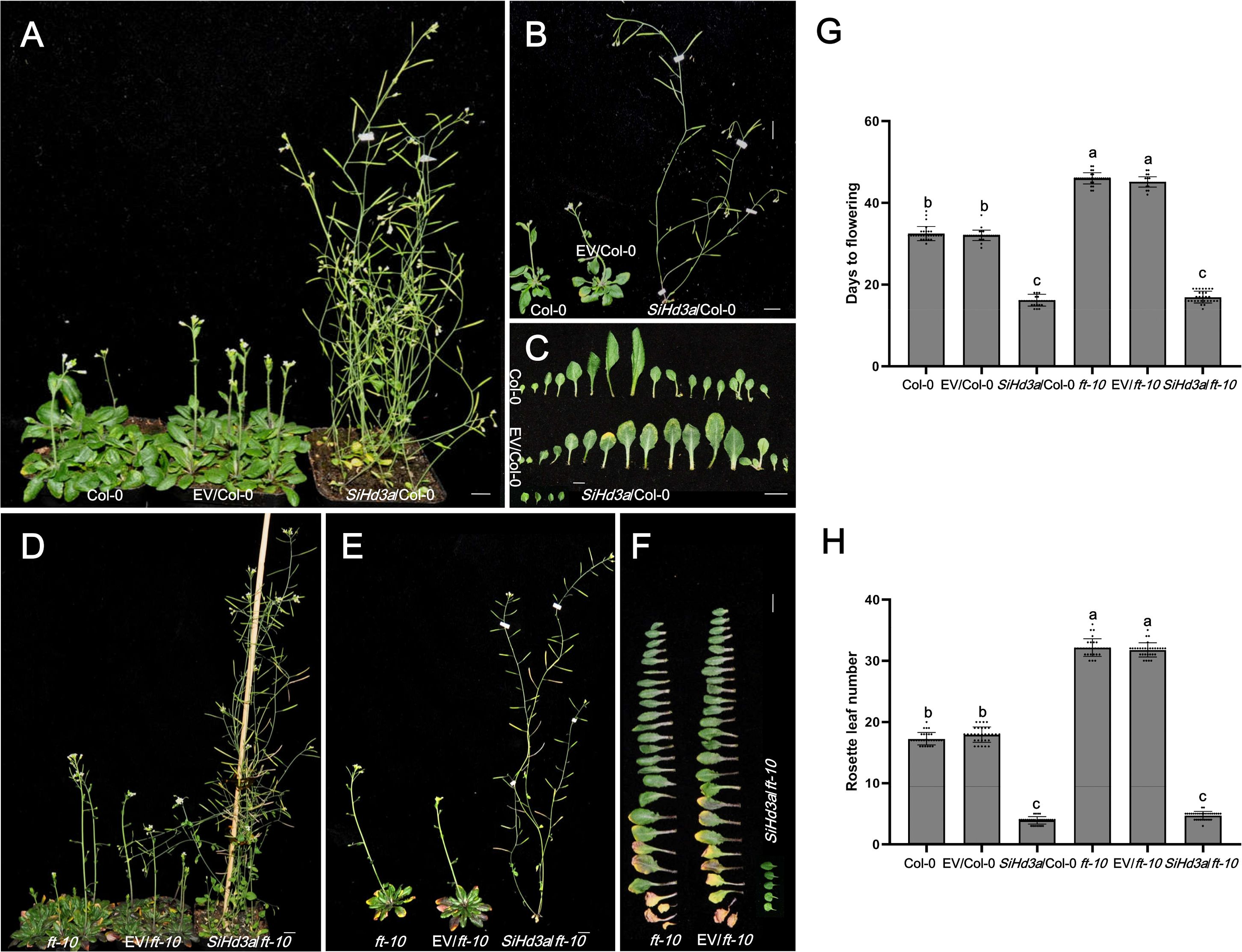

Figure 5. Days to flowering of transgenic Arabidopsis with overexpressed SiFTL under LD condition. (A, B) Photographs of 37 d after sowing Col-0 and SiFTL transgenic lines. (C) Photographs of flowering stages Col-0 and SiFTL transgenic lines leaves. (D, E) Photographs of 51 d after sowing ft-10 mutant and SiFTL transgenic lines. (F) Photographs of flowering stages ft-10 mutant and SiFTL transgenic lines leaves. (G) Days to flowering of flowering stages Col-0, ft-10 mutant and SiFTL transgenic lines. (H) Rosette leaf number of flowering stages Col-0, ft-10 mutant and SiFTL transgenic lines. Col-0 represents the wild-type Arabidopsis Col-0, EV/Col-0 represents overexpressed empty vector C15 in Arabidopsis Col-0, SiFTL/Col-0 represents overexpressed SiFTL in Arabidopsis Col-0. ft-10 represents the Arabidopsis ft-10 mutant, EV/ft-10 represents overexpressed empty vector C15 in ft-10 mutant, SiFTL/ft-10 represents over expressed SiFTL in ft-10 mutant. Values followed by different letters in a column are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05 according to Duncan’s multiple range tests. Bars =1 cm.

Figure 6. Days to flowering of transgenic Arabidopsis with overexpressed SiHd3a under LD condition. (A, B) Photographs of 37 d after sowing Col-0 and SiHd3a transgenic lines. (C) Photographs of flowering stages Col-0 and SiHd3a transgenic lines leaves. (D, E) Photographs of 51 d after sowing ft-10 mutant and SiHd3a transgenic lines. (F) Photographs of flowering stages ft-10 mutant and SiHd3a transgenic lines leaves. (G) Days to flowering of flowering stages Col-0, ft-10 mutant and SiHd3a transgenic lines. (H) Rosette leaf number of flowering stages Col-0, ft-10 mutant and SiHd3a transgenic lines. Col-0 represents the wild-type Arabidopsis Col-0, EV/Col-0 represents overexpressed empty vector C15 in Arabidopsis Col-0, SiHd3a/Col-0 represents overexpressed SiHd3a in Arabidopsis Col-0. ft-10 represents the Arabidopsis ft-10 mutant, EV/ft-10 represents overexpressed empty vector C15 in ft-10 mutant, SiHd3a/ft-10 represents overexpressed SiHd3a in ft-10 mutant. Values followed by different letters in a column are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05 according to Duncan’s multiple range tests. Bars = 1 cm.

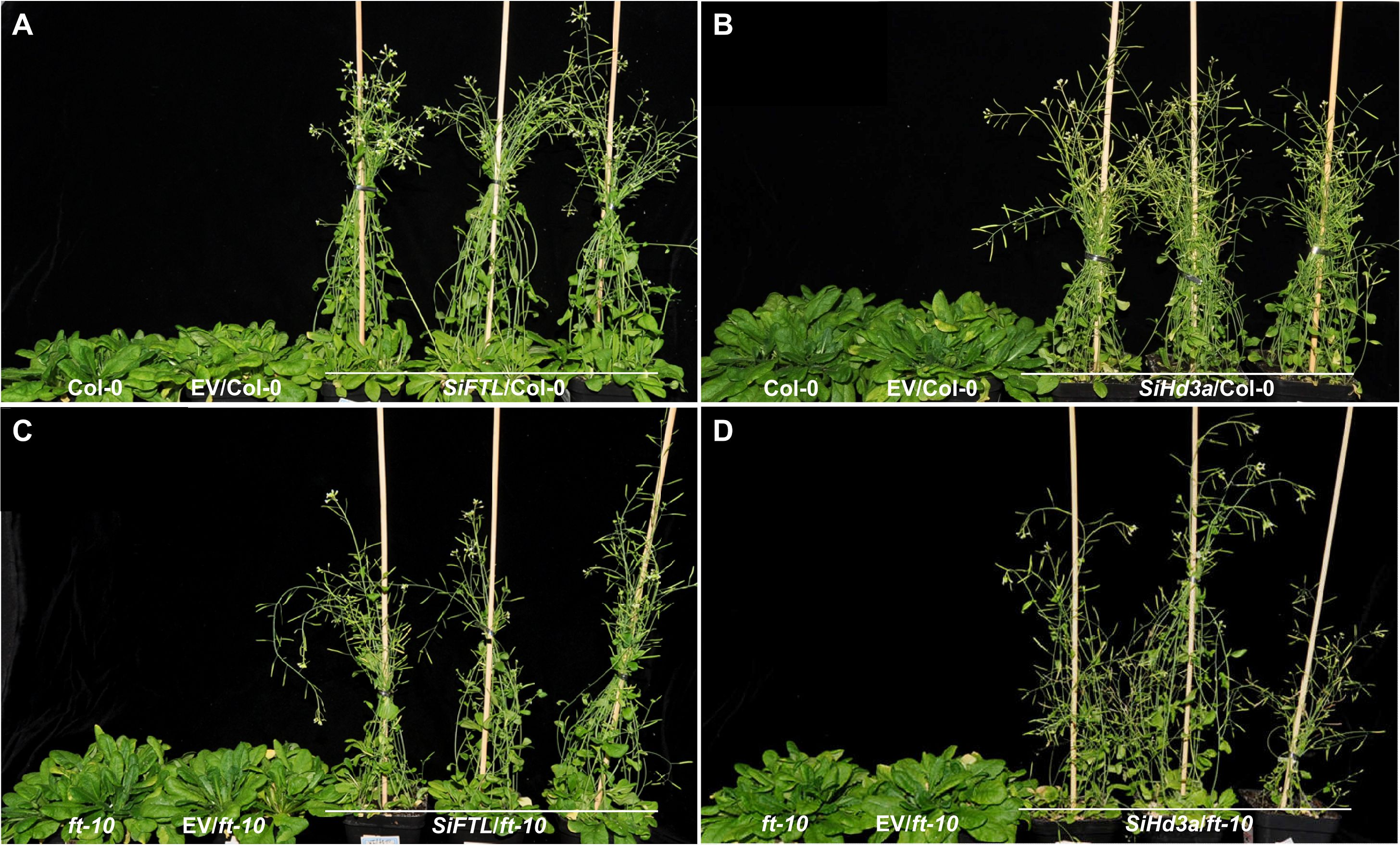

Figure 7. Days to flowering of transgenic Arabidopsis with overexpressed SiFTL or SiHd3a under SD condition. (A) Photographs of 50 d after sowing Col-0 and SiFTL transgenic lines. (B) Photographs of 50 d after sowing Col-0 and SiHd3a transgenic lines. (C) Photographs of 57 d after sowing ft-10 mutant and SiFTL transgenic lines. (D) Photographs of 57 d after sowing ft-10 mutant and SiHd3a transgenic lines.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using JASP 0.95.1 software, with Duncan’s multiple range test at the 5% probability level (Figures 1, 2, 5, 6). The heatmap was created with TBtools with row scaling and row clustering (Chen et al., 2020).

Results

Variations of flowering time in multiple populations

To identify late-flowering varieties of sesame, we conducted phenotypic identification of flowering time on more than 6,000 germplasm accessions and selected BS377 in the field, which was significantly delayed with longer photoperiods, making this an ideal genotype for studying flowering time. To map the candidate genomic region controlling flowering time, we developed several segregating populations by crossing Yuzhi 4 with BS377 (Figure 1A). Flowering time was evaluated in the SY environment using 150 BC1 accessions, 146 F2 accessions, and 128 F2:3 accessions. Additionally, flowering time was assessed for 150 BC1F2 accessions grown in three different locations LH, PY, and NY in 2018 (Figure 1B; Supplementary Table S1). The BC1, F2, and F2:3 populations grown in SY (SD conditions) exhibited more centralized and earlier flowering than the BC1F2 population grown under LD conditions (Figure 1B; Supplementary Table S1).

QTLs for flowering time in sesame

The genetic linkage maps for BC1 and F2 populations were provided by Mei et al. (2023). By aligning the anchored SSR markers, the 14 LGs of the F2 map were integrated with the high-density BC1 map. A total of 152 markers were shared between the two maps, and the marker orders were highly consistent, demonstrating the robustness of the genetic maps (Figure 1C).

To identify candidate QTL regions controlling flowering time, we performed linkage mapping analysis using four populations (BC1, BC1F2, F2, and F2:3) grown in four distinct locations (SY, LH, PY, and NY) (Figure 1C; Supplementary Table S4). In these analyses, we detected two QTLs (qFT_LG08–1 and qFT_LG12-1) in the F2 population, four QTLs (qFT_LG01-1, qFT_LG01-4, qFT_LG08-4, and qFT_LG12-2) in the F2:3 population, four QTLs (qFT_LG01-2, qFT_LG01-3, qFT_LG08-2, and qFT_LG12-3) in the BC1 population, and six QTLs (qFT_LG01-5, qFT_LG05-1, qFT_LG05-2, qFT_LG05-3, qFT_LG08-3, and qFT_LG13-1) in the BC1F2 population.

It is worth noting that several QTLs were identified: qFT_LG01-1, -2, and -3, located closely on LG1, with PVE ranging from 7.1% to 28.1%, were exclusively detected under SD condition; qFT_LG05-1, -2, and -3, clustered on LG5, with PVE from 7.1% to 9.3%, were only found under LD condition; qFT_LG08-1, -2, -3, and -4, situated near each other on LG8, with PVE from 9.5% to 57.6%, were detected under both SD and LD conditions; and qFT_LG12-1, -2, and -3, closely positioned on LG12, with PVE from 2.6% to 17.2%, were identified solely under SD condition.

A total of 16 QTLs were detected in the F2 and BC1 population under the six environments (Figure 1C; Supplementary Table S4). There were four QTL loci (qFT_LG08-1,-2, -3, and-4), which were stable (detected in different environments and/or populations) and with large effect (with a PVE > 9%). These QTLs were consistently detected under both LD and SD conditions, explaining 9.5% to 57.6% of the PVE. By aligning the markers to the sesame reference genome Yuzhi 4, we found that the qFT_LG08-1, -2, -3, and -4 regions overlapped, pinpointing a 13.54-13.95 Mb region (~ 400 kb) on chromosome 11 as the primary candidate region responsible for flowering time.

RNA-seq and qRT-PCR analyses validate candidate genes regulating sesame flowering time

To further identify the candidate genes regulating flowering time, we analyzed the expression profiles of genes within the candidate region (~ 400 kb on chromosome 11) across eight developmental stages in both Yuzhi 4 and BS377 (Figure 2; Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Table S5). After removing adapters and filtering out low-quality and short reads, the clean reads were mapped to the unpublished Yuzhi 4 genome. Within this region, 63 genes were identified for further analysis.

KEGG enrichment analysis highlighted that the “Circadian rhythm-plant” pathway, which includes the genes Sin05626 and Sin05627, is associated with flowering time regulation (Figure 2A; Supplementary Table S5). GO enrichment analysis further supported this, revealing terms related to the “vegetative to reproductive phase transition of the meristem” suggesting potential roles in flowering time control (Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Table S5). Among the candidate genes, Sin05626 and Sin05627 were prioritized as key players in this process. Gene annotation indicated that Sin05626 and Sin05627 encode FLOWERING LOCUS T-like (SiFTL) and HEADING DATE 3A (SiHd3a) proteins, respectively, suggesting their potential as central regulators of flowering time in sesame. The two genes are located adjacent to each other on chromosome 11, separated by only 2.2 kb (Supplementary Table S5).

Expression profiling showed that SiFTL and SiHd3a, among the 63 candidate genes, exhibited expression patterns positively correlated with flowering time (Figure 2B; Supplementary Figure 1). In Yuzhi 4, the expression level of SiFTL increased with flowering formation process (Figure 2B; Supplementary Figure 1). Notably, SiFTL expression was undetectable in BS377 across all developmental stages, suggesting that its loss of expression contributes to the late-flowering phenotype. In contrast, the expression of SiHd3a increased during flowering progression in both Yuzhi 4 and BS377 (Figure 2C; Supplementary Figure 1). To validate these findings, qRT-PCR analysis was performed to assess the expression of candidate genes across eight developmental stages in Yuzhi 4 and BS377. The results confirmed the expression patterns observed in the RNA-seq data, thereby supporting the reliability of the RNA-seq analysis (Figure 2).

Gene structure and phylogenetic analysis of SiFTL and SiHd3a

To investigate the genetic basis of flowering time variation, we analyzed the genomic sequences of SiFTL and SiHd3a in both Yuzhi 4 and BS377 (Figure 3A). In Yuzhi 4, the SiFTL gene comprises five exons, with its first exon and intron spanning 17 bp and 2,094 bp, respectively. A major structural variation was identified in BS377: a 6,265 bp insertion within the first intron of SiFTL, which harbors several conserved domains for transposase and nuclease. While seven SNPs were found in the exonic regions (Supplementary Figure 2), no significant variations were found in the promoter region. The complete absence of SiFTL expression across all examined stages in BS377 suggests that this large insertion may be responsible for its silencing. For SiHd3a, sequence compassion revealed only three exonic SNPs in BS377 (Supplementary Figure 2), with no notable changes in the promoter region.

To elucidate the evolutionary relationships of these genes, we constructed a phylogenetic tree using 57 orthologs from Arabidopsis, rice, soybean, and sesame (Figure 3B; Supplementary Table S6). We identified 11 PEBP genes in sesame, which were divided into three subfamilies: FT-like (4 genes), TFL1-like (5 genes), and MFT-like (2 genes). The FT-like subfamily includes one SiFTL (Sin05626), two Hd3a genes (Sin05627 and Sin22335), and one Hd3a-like gene (Sin08147). Notably, both SiFTL and SiHd3a (Sin05627) were located within the previously identified ~ 400 kb region on chromosome 11. Phylogenetically, SiFTL and SiHd3a cluster closely with the known floral promoters AtFT and AtTSF from Arabidopsis, suggesting their role as key regulators of flowering in sesame.

We further validated their roles through haplotype analysis in the parental lines and the RIL population (Figure 4). Presence of the SiFTL BS377 haplotype band correlated with late flowering, while presence of the SiHd3a Yuzhi 4 haplotype band correlated with early flowering. The results clearly showed that the BS377 haplotype of both SiFTL and SiHd3a were consistently associated with late flowering, whereas the Yuzhi 4 haplotype co-segregated with early flowering phenotype.

Heterologous expression of SiFTL and SiHd3a promotes flowering in Arabidopsis

To functionally validate their roles, we expressed the Yuzhi 4 haplotype of SiFTL and SiHd3a in both wild-type Arabidopsis Col-0 and the late-flowering mutation ft-10 (Figure 5). Under LD condition, heterologous expression of SiFTL significantly accelerated flowering. In the wild-type Col-0 background, SiFTL overexpression lines flowered in 19.1 days with 4.8 rosette leaves, markedly earlier than the controls (32.5 and 32.1 days for Col-0 and the empty vector (EV)/Col-0; 17.3 and 17.9 rosette leaves for Col-0 and EV/Col-0). The OE-SiFTL lines exhibited significantly earlier flowering compared to the controls (Figures 5A–C, G, H), demonstrating that SiFTL can promote flowering in Arabidopsis. In the ft-10 mutant, the flowering times were 46.0 days for ft-10, 45.1 days for EV/ft-10, and 18.4 days for SiFTL/ft-10. The rosette leaf numbers were 32.1 for ft-10, 31.7 for EV/ft-10, and 5.1 for SiFTL/ft-10. While the ft-10 mutant displayed delayed flowering, heterologous expression of SiFTL significantly accelerated flowering (Figures 5D–H), further confirming that SiFTL plays a critical role in regulating flowering time.

To explore the function of SiHd3a in flowering under LD condition, we cloned SiHd3a into the C15 vector and transformed it into Arabidopsis Col-0 and the ft-10 mutant (Figure 6). In wild-type Col-0, the flowering times were 32.5 days for Col-0, 32.1 days for EV/Col-0, and 16.1 days for SiHd3a/Col-0. The rosette leaf numbers were 17.3 for Col-0, 17.9 for EV/Col-0, and 3.9 for SiHd3a/Col-0. The SiHd3a lines showed significantly earlier flowering compared to the controls (Figures 6A–C, G, H), indicating that SiHd3a also plays a key role in flowering regulation. In the ft-10 mutant, the flowering times were 46.0 days for ft-10, 45.1 days for EV/ft-10, and 16.9 days for SiHd3a/ft-10. The rosette leaf numbers were 32.1 for ft-10, 31.7 for EV/ft-10, and 4.7 for SiHd3a/ft-10. Similar to SiFTL, heterologous expression of SiHd3a in the ft-10 mutant significantly rescued the delayed flowering phenotype (Figures 6D–H), further supporting the role of SiHd3a as a key regulator of flowering time in Arabidopsis.

We also tested the OE lines for phenotypic analysis under SD condition (Figure 7). In the SiFTL/Col-0, SiFTL/ft-10, SiHd3a/Col-0, SiHd3a/ft-10 lines, the flowering times were 23.1 d, 19.5 d, 18.5 d, and 18.9 d, respectively. The corresponding rosette leaf numbers were 6.4, 5.2, 4.5, and 4.3. By 57 d, Col-0, EV/Col-0, ft-10, and EV/ft-10 had not developed inflorescences. These results indicated that overexpression of SiFTL and SiHd3a promotes flowering under SD conditions, demonstrating that SiFTL and SiHd3a play key roles in flowering regulation.

Discussion

Flowering time is crucial for crop adaptation and yield, which also impacts biomass and productivity. The photoperiod regulatory pathway for flowering time has been identified in many plants, including Arabidopsis (Wang et al., 2024), rice (Komiya et al., 2008), soybean (Lin et al., 2021), sorghum (Tadesse et al., 2024) and others (Supplementary Table S6). However, sesame flowering is promoted under SD conditions, and it is therefore classified as a SD crop (Zhou et al., 2018). Although some key genes related to flowering time, such as SiCOL1, SiFT, SiFT4, and SiFTL, have been identified (Zhou et al., 2018; López et al., 2023; Sabag et al., 2024), the photoperiod regulation mechanism of sesame flowering time has not yet been reported. In our study, molecular function, gene expression, sequence variations, and transgenic analysis of the key candidate genes in sesame controlling flowering time were comprehensively analyzed.

Genetic resources are important for genetic improvement and crop breeding. The late-flowering material BS377, with late flowering under SD conditions and no flowering in LD conditions, is an ideal system to study flowering time in sesame breeding. Genetic analysis across multiple segregating populations (BC1, F2, F2:3, and BC1F2) derived from crosses between the late-flowering variety ‘BS377’ and the variety ‘Yuzhi 4’ has pinpointed that ~ 400 kb overlapping region on chromosome 11 that exhibits the strongest and most consistent effects on flowering time (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S4). This finding refines the previously reported 1.3 Mb interval on linkage group 11 associated with flowering time under optimal and late sowing condition (Sabag et al., 2024).

Phylogenetic analysis can provide valuable insights into evolutionary relationships and the potential function of candidate genes. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that SiFTL, SiHd3a, Sin08147, and Sin22335 cluster within the FT-like subfamily and are closely related to AtFT, AtTSF, OsRFT1 and OsHd3a (Figure 3B). These genes are well-known florigens that induce flowering in response to photoperiod and circadian rhythms (Komiya et al., 2008; Jin et al., 2015; Colleoni et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024). Since Sin08147 and Sin22335 were not located in the candidate region, we infer that Sin08147 and Sin22335 are not important in regulating sesame flowering time.

In the candidate region, by combining the transcript expression levels and sequence alignment of the two parental lines, SiFTL and SiHd3a were found to be positively correlated with flowering time (Figure 2; Supplementary Figure 1). RNA-seq and qRT-PCR analyses revealed that the expression levels of SiFTL and SiHd3a in Yuzhi 4 exhibited a continuous upregulation during flowering progression. These expression profiles were consistent with previous reports indicating that these candidate genes are highly expressed during flowering (Komiya et al., 2008; Sabag et al., 2024). Recent studies have investigated SiFTL and SiHd3a genes regulating flowering (López et al., 2023; Sabag et al., 2024). However, the expression profile of SiFTL diverged from prior findings. Previous results indicated high expression of SiFTL in K3 and NEB varieties following floral induction (López et al., 2023). Conversely, SiHd3a does not appear to regulate the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth in K3 and NEB varieties. Additionally, no significant differences in its expression levels were observed between the early-flowering S-490 and late-flowering S-10 genotypes. These findings suggest that SiFTL and SiHd3a may not be primary flowering candidates, likely due to the limited growth stages analyzed in earlier studies (López et al., 2023; Sabag et al., 2024). In our study, SiFTL and SiHd3a were identified as candidate genes through analyzing their expression patterns across eight developmental stages.

Comparative genomic alignment revealed a 6,265 bp insertion within the first intron of SiFTL in BS377, a structural alteration that is likely to disrupt proper transcript stability and thereby contribute to the observed silencing (Figures 2, 3; Supplementary Figure 1). This finding parallels the ft-10 mutant in Arabidopsis, in which a T-DNA insertion in the first intron of AtFT abolishes FT expression and confers pronounced late flowering (Liu et al., 2014). Collectively, these data indicate that the transcriptional silencing of SiFTL in BS377 is the primary cause of its delayed flowering. Although previous studies suggest that the C/T allele in SiFTL contributes to flowering time regulation (Sabag et al., 2024), this study reveals that the structure of SiFTL in BS377 differs from that in S-490 and S-10, and plays a pivotal role as a key determinant of flowering time. For SiHd3a, three SNPs were detected in the exonic regions of BS377 compared to the Yuzhi 4, with no significant variations observed in its promoter region. In our study, SiFTL and SiHd3a cluster within the FT-like subfamily and are tightly clustered on chromosome 11, separated by only 2.2 kb (Supplementary Table S5). This aligns with prior findings that these genes are physically linked (Sabag et al., 2024). In the rice system, where RICE FLOWERING LOCUS T 1 (RFT1) and OsHd3a are closely linked (11.5 kb apart) on chromosome 6 (Komiya et al., 2008), this finding provides clues that SiFTL and SiHd3a are important genes for flowering time.

Based on these sequence differences, molecular markers of SiFTL and SiHd3a were designed and validated in a RIL population (Figure 4). Based on RIL population analysis, we found that SiFTL and SiHd3a genes were closely linked and showed complete co-segregation with flowering time. RIL population resequencing analysis suggests that this locus, rather than the two genes themselves, is associated with sesame flowering time (Supplementary Figure 4). However, to determine whether SiFTL and SiHd3a are key candidate genes for regulating flowering time in sesame, each gene’s needs to be verified using gene editing technology. In addition, the specific primers designed for SiFTL and SiHd3a can be used as molecular markers to assist in the selective breeding of sesame at the flowering stage, or provide valuable genetic resources for breeding early maturing sesame varieties.

Heterologous expression of SiFTL and SiHd3a in Arabidopsis significantly accelerated flowering under LD and SD conditions (Figures 5–7). However, at 57 d under SD conditions, Col-0 and ft-10 did not develop inflorescences. Moreover, the flowering time of Arabidopsis overexpressing SiFTL or SiHd3a did not differ significantly between LD and SD conditions. This indicates that SiFTL and SiHd3a act as inducers of flowering under SD conditions as well as LD conditions, suggesting they may function as universal floral activators downstream. This study further elucidates the regulatory roles of SiFTL and SiHd3a in sesame flowering through their heterologous overexpression in Arabidopsis Col-0 and ft-10 mutant, building upon and extending the findings of Sabag et al. (2024).

Conclusions

Flowering time is an important adaptive character that significantly influences plant biomass and adaptability. In this study, we pinpoint ~ 400 kb region on chromosome 11 that exhibits the strongest and most stable effect on flowering time. Transcript profiling revealed a steady increase in the expression of SiFTL and SiHd3a during flower development in Yuzhi 4. Integrative analyses of gene structure and expression data further demonstrated that the silencing of SiFTL transcripts in the variety BS377 underlies its markedly delayed flowering. Phylogenetic analysis suggested that SiFTL and SiHd3a are orthologues of AtFT and are associated with flowering in sesame. Overexpression of SiFTL and SiHd3a in Arabidopsis Col-0 and ft-10 mutation accelerated flowering under both LD and SD conditions, suggesting they may function as universal floral activators downstream. Finally, in the cultivar Yuzhi 4, the SiFTL and SiHd3a locus is closely associated with precocity. Overall, our results demonstrate that SiFTL and SiHd3a serve as crucial regulators of flowering in sesame, providing valuable insights for the molecular breeding of early-maturing cultivars.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

FZ: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. ZD: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. CC: Funding acquisition, Software, Writing – review & editing. KW: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XJ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JW: Writing – review & editing. RZ: Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. YF: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. RH: Writing – review & editing. YL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. HM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-14), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M750821), the Key Research Project of the Shennong Laboratory (SN01-2022-04), the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (252300421667), the Key Research and Development Project of Henan (242102110277, 232102110176), the HAAS Fund for Abroad Training of Young Scientists, the Projects of Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2024YQ19, 2024TD22, 2025ZC42, 2025JC19).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledged Professor Yingqiang Wen, Northwest A&F University, for kindly providing the vectors of C15, and Associate Researcher Zhang Xiaomei, Institute of Crop Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, for kindly providing the Arabidopsis ft-10 mutant.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1716212/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Candidate genes identification through RNA-seq. (A) GO enrichment analysis for genes in the candidate regions. (B) Heatmap for genes in the candidate regions across eight developmental stages of Yuzhi 4 and BS377 new leaves. S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8 represent the leaves of the Yuzhi 4 variety at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35 and 40 days after sowing. S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8 represent the leaves of the BS377 variety at 5, 15, 35, 60, 65, 70, 75, and 90 d after sowing. S6 and S7 indicate the pre-budding and post-budding stages, respectively, while S8 denotes the post-flowering stage.

Supplementary Figure 2 | Sequence alignment and variation analysis of Sin05626 and Sin05627 genes in Yuzhi 4 and BS377. (A) Sequence alignment of SiFTL (Sin05626) between BS377 and Yuzhi 4. (B) Sequence alignment of SiHd3a (Sin05627) between BS377 and Yuzhi 4.

Supplementary Figure 3 | Schematic of primer design for genotyping SiFTL and SiHd3a loci in the RIL population. (A) Primer design of SiFTL in Yuzhi 4 and BS377. (B): Primer design of SiHd3a in Yuzhi 4 and BS377. Pink represents insert sequence; Yellow represents primer; Green represents same sequence.

Supplementary Figure 4 | Haplotype composition at the SiFTL and SiHd3a loci across the RIL population. (A) Genotype heat map of candidate interval. (B) Comparative analysis of flowering time of two haplotypes. Haplotype 1 (HAP1) represents the BS377 haplotypes at the SiFTL and SiHd3a loci. HAP2 represents the Yuzhi 4 haplotypes at the SiFTL and SiHd3a loci.

References

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., and Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

Chardon, F. and Damerval, C. (2005). Phylogenomic analysis of the PEBP gene family in cereals. J. Mol. Evol. 61, 579–590. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0179-4

Chen, C., Chen, H., Zhang, Y., Thomas, H. R., Frank, M. H., He, Y., et al. (2020). TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y., and Gu, J. (2018). fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560

Colleoni, P. E., van Es, S. W., Winkelmolen, T., Immink, R. G. H., and van Esse, G. W. (2024). Flowering time genes branching out. J. Exp. Bot. 75, 4195–4209. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erae112

Corbesier, L., Vincent, C., Jang, S., Fornara, F., Fan, Q., Searle, I., et al. (2007). FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science 316, 1030–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1141752

Dong, L., Lu, Y., and Liu, S. (2020). Genome-wide member identification, phylogeny and expression analysis of PEBP gene family in wheat and its progenitors. PeerJ 8, e10483. doi: 10.7717/peerj.10483

Gu, H., Zhang, K., Chen, J., Gull, S., Chen, C., Hou, Y., et al. (2022). OsFTL4, an FT-like gene, regulates flowering time and drought tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Rice 15, 47. doi: 10.1186/s12284-022-00593-1

Hsu, C. Y., Adams, J. P., Kim, H., No, K., Ma, C., Strauss, S. H., et al. (2011). FLOWERING LOCUS T duplication coordinates reproductive and vegetative growth in perennial poplar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 10756–10761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104713108

Huang, B., Qian, P., Gao, N., Shen, J., and Hou, S. (2017). Fackel interacts with gibberellic acid signaling and vernalization to mediate flowering in Arabidopsis. Planta 245, 939–950. doi: 10.1007/s00425-017-2652-5

Jin, S., Jung, H. S., Chung, K. S., Lee, J. H., and Ahn, J. H. (2015). FLOWERING LOCUS T has higher protein mobility than TWIN SISTER OF FT. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 6109–6117. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv326

Kloosterman, B., Anithakumari, A. M., Chibon, P. Y., Oortwijn, M., van der Linden, G. C., Visser, R. G., et al. (2012). Organ specificity and transcriptional control of metabolic routes revealed by expression QTL profiling of source–sink tissues in a segregating potato population. BMC Plant Biol. 12, 17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-17

Kobayashi, K., Yasuno, N., Sato, Y., Yoda, M., Yamazaki, R., Kimizu, M., et al. (2012). Inflorescence meristem identity in rice is specified by overlapping functions of three AP1/FUL-like MADS box genes and PAP2, a SEPALLATA MADS box gene. Plant Cell. 24, 1848–1859. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.097105

Kojima, S., Takahashi, Y., Kobayashi, Y., Monna, L., Sasaki, T., Araki, T., et al. (2002). Hd3a, a rice ortholog of the Arabidopsis FT gene, promotes transition to flowering downstream of Hd1 under short-day conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 1096–1105. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf156

Komiya, R., Ikegami, A., Tamaki, S., Yokoi, S., and Shimamoto, K. (2008). Hd3a and RFT1 are essential for flowering in rice. Development 135, 767–774. doi: 10.1242/dev.008631

Kong, F., Liu, B., Xia, Z., Sato, S., Kim, B. M., Watanabe, S., et al. (2010). Two coordinately regulated homologs of FLOWERING LOCUS T are involved in the control of photoperiodic flowering in soybean. Plant Physiol. 154, 1220–1231. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.160796

Kumazaki, T., Yamada, Y., Karaya, S., Kawamura, M., Hirano, T., Yasumoto, S., et al. (2009). Effects of day length and air and soil temperatures on sesamin and sesamolin contents of sesame seed. Plant Prod. Sci. 12, 481–491. doi: 10.1626/pps.12.481

Kumazaki, T., Yamada, Y., Karaya, S., Tokumitsu, T., Hirano, T., Yasumoto, S., et al. (2008). Effects of day length and air temperature on stem growth and flowering in sesame. Plant Prod. Sci. 11, 178–183. doi: 10.1626/pps.11.178

Li, X., Chen, L., Yao, L., Zou, J., Hao, J., and Wu, W. (2021). Calcium-dependent protein kinase CPK32 mediates calcium signaling in regulating Arabidopsis flowering time. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, nwab180. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwab180

Li, H., Ye, G., and Wang, J. (2007). A modified algorithm for the improvement of composite interval mapping. Genetics 175, 361–374. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.066811

Lifschitz, E., Eviatar, T., Rozman, A., Shalit, A., Goldshmidt, A., Amsellem, Z., et al. (2006). The tomato FT ortholog triggers systemic signals that regulate growth and flowering and substitute for diverse environmental stimuli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 6398–6403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601620103

Lin, X., Liu, B., Weller, J. L., Abe, J., and Kong, F. (2021). Molecular mechanisms for the photoperiodic regulation of flowering in soybean. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 63, 981–994. doi: 10.1111/jipb.13021

Liu, L., Adrian, J., Pankin, A., Hu, J., Dong, X., von Korff, M., et al. (2014). Induced and natural variation of promoter length modulates the photoperiodic response of FLOWERING LOCUS T. Nat. Commun. 5, 4558. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5558

Liu, J., Zhao, F. L., Guo, Y., Fan, X. C., Wang, Y. J., and Wen, Y. Q. (2019). The ABA receptor-like gene VyPYL9 from drought-resistance wild grapevine confers drought tolerance and ABA hypersensitivity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 138, 543–558. doi: 10.1007/s11240-019-01650-2

Livak, K. J. and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

López, M., Larrea, H., Alvarenga, N., González, D., and Iehisa, J. C. M. (2023). CONSTANS-like genes are associated with flowering time in sesame. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 35, 341–353. doi: 10.1007/s40626-023-00290-4

Mäckelmann, S., Känel, A., Kösters, L. M., Lyko, P., Prüfer, D., Noll, G. A., et al. (2024). Gene complementation analysis indicates that parasitic dodder plants do not depend on the host FT protein for flowering. Plant Commun. 5, 100826. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2024.100826

Mei, H., Cui, C., Liu, Y., Du, Z., Wu, K., Jiang, X., et al. (2023). QTL analysis of traits related to seed size and shape in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). PloS One 18, e0293155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0293155

Meng, L., Li, H., Zhang, L., and Wang, J. (2015). QTL IciMapping: Integrated software for genetic linkage map construction and quantitative trait locus mapping in bi-parental populations. Crop J. 3, 169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2015.01.001

Miao, H. M., Langham, D. R., and Zhang, H. Y. (2021). “Botanical descriptions of sesame,” in The sesame genome. Compendium of plant genomes. Eds. Miao, H. M., Zhang, H. Y., and Kole, C. (Springer, Cham), 19–57.

Neumaier, N. and James, A. T. (1993). Exploiting the long-juvenile trait to improve adaptation of soybeans to the tropics. ACIAR Food Legume Newsl. 18, 12–14.

Ortega, R., Hecht, V. F. G., Freeman, J. S., Rubio, J., Carrasquilla-Garcia, N., Mir, R. R., et al. (2019). Altered expression of an FT cluster underlies a major locus controlling domestication-related changes to chickpea phenology and growth habit. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 824. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00824

Rinne, P. L., Welling, A., Vahala, J., Ripel, L., Ruonala, R., Kangasjärvi, J., et al. (2011). Chilling of dormant buds hyperinduces FLOWERING LOCUS T and recruits GA-inducible 1,3-beta-glucanases to reopen signal conduits and release dormancy in Populus. Plant Cell. 23, 130–146. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.081307

Sabag, I., Pnini, S., Morota, G., and Peleg, Z. (2024). Refining flowering date enhances sesame yield independently of day-length. BMC Plant Biol. 24, 711. doi: 10.1186/s12870-024-05431-8

Schiessl, S., Samans, B., Hüttel, B., Reinhard, R., and Snowdon, R. J. (2014). Capturing sequence variation among flowering-time regulatory gene homologs in the allopolyploid crop species Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 404. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00404

Sinha, S. K., Tomar, D. P. S., and Deshmukh, P. S. (1973). Photoperiodic response and yield potential of sesamum genotypes. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 33, 293–296.

Song, Y. H., Ito, S., and Imaizumi, T. (2013). Flowering time regulation: photoperiod- and temperature-sensing in leaves. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 575–583. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.05.003

Suddihiyam, P., Steer, B. T., and Turner, D. W. (1992). The flowering of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) in response to temperature and photoperiod. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 43, 1101–1116. doi: 10.1071/AR9921101

Tadesse, D., Yee, E. F., Wolabu, T. W., Wang, H., Yun, J., Grosjean, N., et al. (2024). Sorghum SbGhd7 is a major regulator of floral transition and directly represses genes crucial for flowering activation. New Phytol. 242, 786–796. doi: 10.1111/nph.19591

Tamaki, S., Matsuo, S., Wong, H. L., Yokoi, S., and Shimamoto, K. (2007). Hd3a protein is a mobile flowering signal in rice. Science 316, 1033–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.1141753

Taoka, K., Ohki, I., Tsuji, H., Furuita, K., Hayashi, K., Yanase, T., et al. (2011). 14-3–3 proteins act as intracellular receptors for rice Hd3a florigen. Nature 476, 332–335. doi: 10.1038/nature10272

Voorrips, R. E. (2002). MapChart: software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 93, 77–78. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.77

Wang, F., Han, T., and Jeffrey Chen, Z. (2024). Circadian and photoperiodic regulation of the vegetative to reproductive transition in plants. Commun. Biol. 7, 579. doi: 10.1038/s42003-024-06275-6

Wang, S., Li, H., Li, Y., Li, Z., Qi, J., Lin, T., et al. (2020). FLOWERING LOCUS T improves cucumber adaptation to higher latitudes. Plant Physiol. 182, 908–918. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.01215

Wei, L., Miao, H., Zhao, R., Han, X., Zhang, T., and Zhang, H. (2013). Identification and testing of reference genes for sesame gene expression analysis by quantitative real-time PCR. Planta 237, 873–889. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1805-9

Zhao, F., Li, G., Hu, P., Zhao, X., Li, L., Wei, W., et al. (2018). Identification of basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factors reveals candidate genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis from the strawberry white-flesh mutant. Sci. Rep. 8, 2721. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21136-z

Keywords: sesame, flowering time, linkage mapping, flowering locus T like, heading date 3a

Citation: Zhao F, Du Z, Cui C, Wu K, Jiang X, Wang J, Zhang R, Fan Y, Henry RJ, Liu Y, Mei H and Zhang H (2025) SiFTL and SiHd3a are positive regulators of flowering time in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 16:1716212. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1716212

Received: 30 September 2025; Accepted: 19 November 2025; Revised: 14 November 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Baohua Wang, Nantong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Luming Yang, Henan Agricultural University, ChinaLinhai Wang, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China

Adrián Pérez Rial, University of Cordoba, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Zhao, Du, Cui, Wu, Jiang, Wang, Zhang, Fan, Henry, Liu, Mei and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanyang Liu, bGl1eWFueWFuZzAwMUAxNjMuY29t; Hongxian Mei, bWVpaHgyMDAzQDEyNi5jb20=; Haiyang Zhang, emhhbmdoYWl5YW5nQHp6dS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Fengli Zhao

Fengli Zhao Zhenwei Du1,2†

Zhenwei Du1,2† Chengqi Cui

Chengqi Cui Ruping Zhang

Ruping Zhang Robert J. Henry

Robert J. Henry Yanyang Liu

Yanyang Liu Hongxian Mei

Hongxian Mei