- 1Plant Virology Lab, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR)-Institute of Himalayan Bioresource Technology (IHBT), Palampur, Himachal Pradesh, India

- 2Academy of Scientific and Innovative Research (AcSIR), Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh, India

- 3Laboratory of Cell Cycles of Algae, Centre Algatech, Institute of Microbiology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Třeboň, Czechia

While many plant viruses cause diseases that reduce crop yield, quality, and overall plant health, not all viruses are purely detrimental. Under certain conditions, some can confer beneficial effects, including improving abiotic stress tolerance, enhancing immunity, or even increasing pollination efficiency. RNA viruses, though most often associated with disease, can also establish symbiotic relationships with their hosts that are mutualistic, commensal, or conditionally beneficial depending on environmental factors. This mini-review summarizes how mild viral infections can protect plants against more severe pathogens (cross-protection), induce signaling and epigenetic changes that enhance stress tolerance, and serve as tools for gene delivery and crop improvement. Collectively, these findings underscore the potential of RNA viruses to support plant adaptation and survival, offering innovative possibilities for sustainable agriculture and climate resilience.

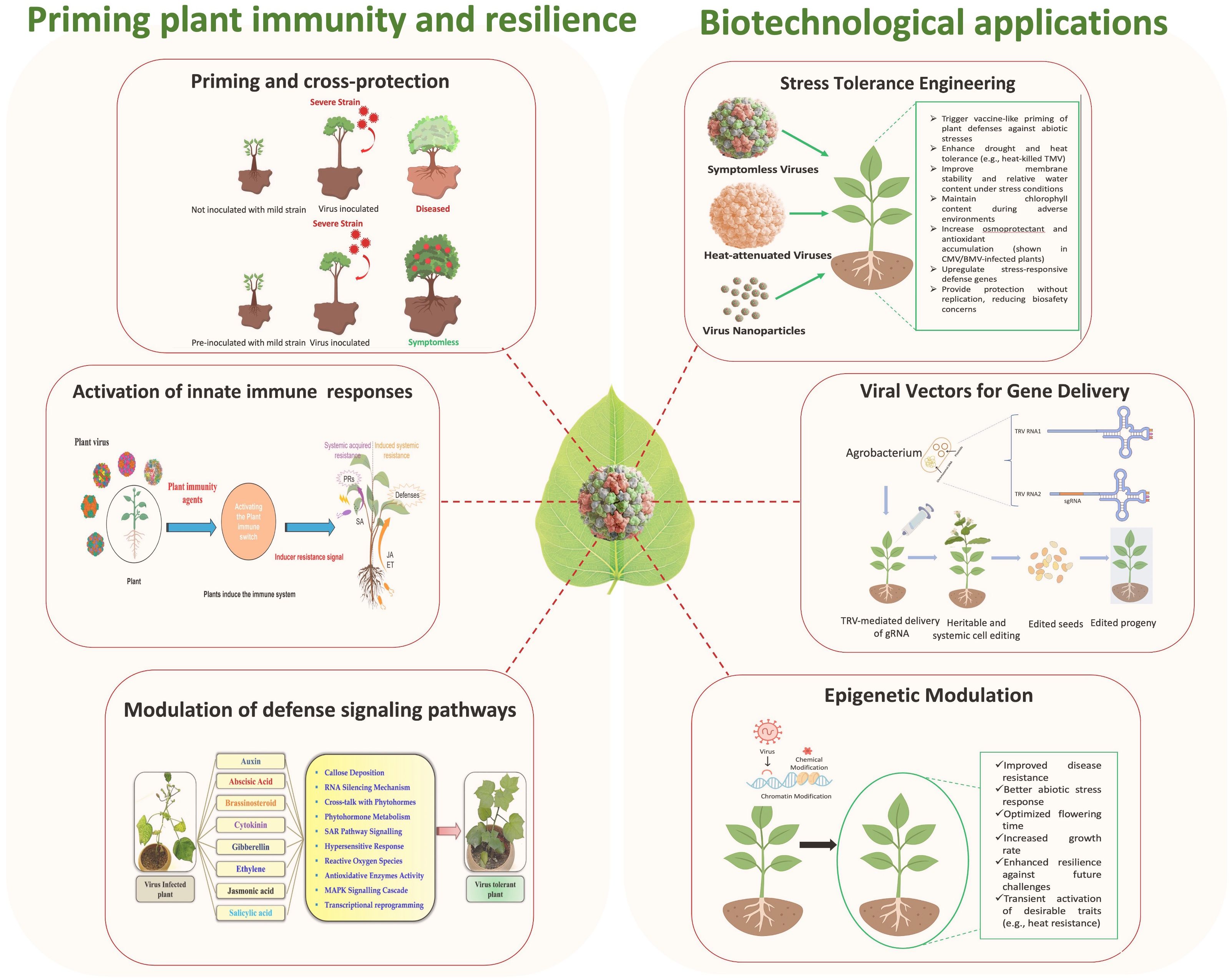

Graphical Abstract. Mutualistic roles of plant RNA viruses in priming plant immunity and advancing biotechnological applications. Beyond their pathogenic reputation, RNA viruses can enhance plant resilience by priming immune responses, conferring cross-protection, and modulating defense signaling pathways. At the same time, biotechnological applications leverage viral symbiosis for stress tolerance engineering, gene delivery vectors, and epigenetic modulation of traits. Together, these interactions highlight the potential of viruses as ecological partners and innovative tools for sustainable crop improvement.

1 Introduction

RNA viruses are widely recognized as agents of disease in animals and plants. In humans and livestock, influenza viruses cause seasonal epidemics, rabies virus induces lethal encephalitis, and foot-and-mouth disease virus devastates livestock herds (Woolhouse et al., 2013; Villa et al., 2021). In plants, RNA viruses such as tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) affect tobacco, tomatoes, and peppers, causing mottling, leaf distortion, and stunted growth (Prabahar et al., 2015). Potato virus Y (PVY) infects potatoes, peppers, and tomatoes, reducing tuber quality (Scholthof et al., 2011). Rice tungro virus threatens rice cultivation in Southeast Asia (Tyagi et al., 2008), and cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) infects over 1,200 species, causing leaf mosaics and malformed fruits while spreading efficiently via aphid vectors (Ando et al., 2019; Rattan et al., 2022).

However, not all plant-virus interactions are harmful. Recent studies reveal that many RNA viruses can exist without causing disease and may confer benefits, including immune system conditioning, stress resilience, competitive advantages, evolutionary adaptability, and facilitation of symbiotic partnerships. Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) is a plant RNA virus that often persists asymptomatically in its host plants. Studies have shown that CMV infection can enhance plant resilience to abiotic stresses such as drought and freezing by increasing levels of osmoprotectants and antioxidants (Xu et al., 2008). This suggests that CMV can function as a mutualistic partner under specific environmental conditions, contributing to the plant’s survival and adaptation. In yeast, killer viruses produce toxins that eliminate competing strains, protecting host populations (Schmitt and Breinig, 2002). Viral genetic material can also drive evolutionary innovation by influencing host gene regulation or integrating into host genomes (Sanjuán and Domingo-Calap, 2016; Broecker and Moelling, 2019). In plants, RNA viruses can subtly modulate physiology by altering hormone and stress signaling or small RNA pathways, sometimes enhancing growth, defense, or reproduction. For example, CMV infection alters floral scent to attract bumblebees, increasing pollination and seed set despite pathogenic effects (Groen et al., 2016). Furthermore, RNA viruses have been repurposed for gene delivery and therapeutic applications (Zhu et al., 2023; Lundstrom, 2023).

In this mini review, we explore how RNA viruses can function as benefactors of their plant hosts. We discuss several facets of this phenomenon: (1) Pathogens turned protectors, where viral infections boost plant immunity or protect against other diseases; (2) Mutualistic viruses enhancing stress tolerance and their emerging applications in agriculture; (3) the use of mild RNA viruses as tools for gene delivery and epigenetic modulation of traits; and finally (4) the challenges and future prospects of harnessing viral symbioses in plant science and biotechnology. By examining recent findings and longstanding examples, we aim to provide a comprehensive view of the “bright side” of plant RNA viruses and outline how these insights can be translated into innovative strategies for crop improvement and sustainable agriculture.

2 Pathogens turned protectors: the defense-boosting side of RNA viruses

Despite their notorious reputation for spreading disease, certain RNA viruses have the paradoxical ability to shield their hosts from other infections. Complex immune systems have developed in plants, and some viral infections activate these defenses in ways that make the plant more resilient to future assaults. Here, we go over some defense-enhancing strategies that can turn an “enemy” virus into the plant’s protector.

2.1 Priming and cross-protection

Plants (or other hosts) can be infected by a mild or attenuated strain of a virus, which can then prevent or lessen the effects of a subsequent infection by a more virulent strain of the same or a related virus. Competition for resources, cellular site occupancy, or immune system activation are the causes of this. In citrus horticulture, for instance, weak strains of the Citrus tristeza virus (CTV) are used to shield trees from more severe strains; this technique is called mild strain cross-protection (MSCP). By inoculating citrus plants with a mild CTV isolate, this method can stop or lessen the impact of later infections by more virulent strains (Lee and Keremane, 2013; Licciardello et al., 2023). Similar protection has been achieved in case of Sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV) (Xu et al., 2021), cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) (Zhou and Zhou, 2012), papaya ringspot virus (PRSV) (Resour et al., 2025) etc. By identifying or generating hypovirulent mutant strains, which are virus variants with reduced virulence that cause mild or no disease symptoms, researchers have explored their potential to trigger protective responses in host plants. Similar strategies have been applied to other crop-virus systems, such as papaya ringspot virus in papaya and sugarcane mosaic virus in sugarcane. In terms of mechanism, cross-protection frequently depends on the host’s RNA silencing module: the mild virus generates replicative intermediaries of double-stranded RNA that cause gene silencing, thereby targeting the genomes of any inbound related virus. In essence, the plant’s antiviral defense (particularly small interfering RNAs) gets primed by the mild strain, so that a subsequent invasion by a related virus is rapidly suppressed. This was demonstrated in studies of TMV and other viruses, where pre-infection induced virus-specific small RNAs and other defense responses that correlated with resistance to a challenge inoculation (Voloudakis et al., 2025). Intriguingly, there are instances of heterologous protection-a mild virus defending against another virus-which may arise from widespread immune stimulation, but cross-protection is typically virus-strain-specific. All things considered, viral priming and cross-protection show a definite mutualistic result: the host is protected from lethal virus strains (and possibly other infections) while the virus obtains a viable host in which to reproduce. In the agricultural sector, this approach can be applied by using mild variants of pepino mosaic virus to protect greenhouse tomatoes from more severe strains, thus offering a chemical-free disease control strategy compatible with sustainable crop production (Khankhum et al., 2016).

2.2 Activation of innate immune responses

In addition to intentional cross-protection techniques, a plant may become more defensive even after an unintentional viral infection. The generic features of viruses, such as double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) produced during replication as a “non-self” molecular pattern, can be recognized by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) in plant cells, leading to their activation (Hur, 2019). This triggers the plant’s innate immune responses, leading to the production of defense proteins, RNA-silencing enzymes, and antiviral compounds. These responses not only help combat the current pathogen but also prime the plant’s defenses more broadly, enhancing resistance against future infections. A mild virus infection, for instance, may result in the systemic buildup of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, increased antioxidant levels, or reinforced cell walls, all of which may unintentionally reduce the plant’s susceptibility to unrelated diseases like bacteria or fungus. Thus, in addition to fighting the current infection, RNA viruses prime the plant’s immune system thus making it possible for the plant to react more robustly to later attacks by various diseases, such as fungus and bacteria (Pumplin and Voinnet, 2013; Leonetti et al., 2021). According to research, some viruses trigger the immune response by boosting salicylic acid or other defense hormones, which in turn cross-activates pathways that provide resistance against recurrent infections. In one instance, a common bean’s latent endornavirus infection was linked to increased basal expression of defensive genes, which enabled the plants to withstand a subsequent challenge from a pathogenic virus (Khankhum et al., 2016). The net impact, however, may be a sort of immune “alert” status that helps the plant in the event of additional attack when a virus causes moderate immune responses without leading to severe disease.

2.3 Modulation of defense signaling pathways

Upon infection, RNA viruses can interfere with the plant’s immune signaling to avoid detection and suppression. While these action aim to facilitate viral replication, they can also lead to a state of heightened alertness in the plant’s immune system (Ellendorff et al., 2009). For example, it has been demonstrated that Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV) infection increases the expression of genes involved in the abscisic acid (ABA) signaling pathway. The virus suppresses the plant’s immune response to facilitate infection. However, the mild activation of ABA can prime the plant to tolerate other abiotic stresses (like drought or salinity), leading to an unintended increase in stress tolerance (Shukla et al., 2025). The virus’s modification of hormonal crosstalk results in a “unintended increase in stress tolerance,” according to Shukla et al. (2025). In other situations, viruses that increase salicylic acid to evade detection may also increase the plant’s resistance to other diseases, as salicylic acid is an important signal for defense against bacteria and biotrophic fungi. Conversely, a virus that interferes with jasmonate signaling, possibly to increase the plant’s appeal to insect vectors, may unintentionally decrease herbivory by non-vector insects, which would be advantageous to the host. Although these outcomes are context-dependent and not fully understood, they illustrate that viral manipulation of host immunity can occasionally produce conditionally beneficial effects, highlighting a nuanced spectrum in virus-host interactions where primarily harmful infections may confer incidental advantages under specific environmental or stress conditions.

3 Exploring the role of mutualistic RNA viruses in enhancing crop resilience and biotech applications

3.1 Stress tolerance engineering

Emerging research highlights the remarkable potential of viruses in enhancing plant stress tolerance. A striking example comes from the tripartite symbiosis described by (Urayama et al., 2024), where panic grass (Dichanthelium lanuginosum), its fungal endophyte (Curvularia protuberata), and the associated Curvularia thermal tolerance virus (CThTV) enable survival in geothermal soils with temperatures reaching 65°C. Extending this principle, inoculation of rice and t2023omato with similar fungus-virus combinations has significantly improved heat tolerance (Al-Hamdani et al., 2015). Inspired by such natural partnerships, biotechnologists are now exploring engineered viral symbionts to fortify crops against climate change. For instance, modified Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) has been used as a carrier to prime immune responses and enhance drought resistance without causing disease (Mandadi and Scholthof, 2013), while TMV nanoparticles mitigate oxidative stress under water-limited conditions (Al-Khayri et al., 2023). Similarly, persistent, symptomless viruses such as endornaviruses in beans and squash are being investigated as potential tools for strengthening crop performance (Uchida et al., 2021). Parallel efforts are also focused on discovering and utilizing naturally occurring, non-symptomatic viruses that improve plant resilience, such as those found in rice and cucumber (Xu et al., 2008). Plant breeders are beginning to screen crops for such beneficial infections, while synthetic biology approaches aim to repurpose viruses into safe bioengineering tools. These engineered viruses can deliver genes for stress tolerance, growth, and disease resistance, offering a sustainable alternative to conventional transgenic methods … Beyond replicating viruses, virus infections such as cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) and Brome mosaic virus (BMV), as well as non-replicating viral particles including heat-killed Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), have been shown to trigger protective, “vaccine-like” responses against abiotic stresses (Tomitaka et al. 2024). For example, Xu et al. (2008) demonstrated that CMV or BMV infections delayed drought-symptom onset and increased osmoprotectant and antioxidant levels, providing evidence of virus-mediated abiotic stress resilience. More recently, Augustine et al. (2023) showed that treatment of Nicotiana tabacum with heat-killed TMV enhanced drought and heat tolerance by improving membrane stability, relative water content, chlorophyll content, and upregulating stress-responsive genes. Together, these findings suggest that viruses, long considered only as pathogens, may serve as “viral probiotics,” offering farmers novel, eco-friendly means to enhance stress tolerance in crops. While further research is needed to ensure biosafety and long-term stability, the growing body of evidence positions viruses not merely as threats but as promising allies in sustainable agriculture. By harnessing both natural viral partnerships and engineered viral tools, we may unlock innovative strategies to help crops withstand the increasing challenges of climate change.

3.2 Viral vectors for gene delivery

Viral vectors are emerging as efficient tools for plant gene delivery, offering rapid and systemic expression of beneficial traits. Symbiotic or persistent RNA viruses, which naturally coexist with plants without causing disease, are being engineered to deliver genes for stress tolerance, growth, and disease resistance. Their ability to spread through plant tissues provides a sustainable alternative to conventional transgenic methods. Engineered Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) particles and attenuated forms of Alfalfa mosaic virus (AMV) and Cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV) are now used to carry functional genes and gene-editing tools such as CRISPR/Cas9 (Mahmood et al., 2023). Unlike traditional genetic modification, virus-mediated editing can create targeted, inheritable changes without integrating foreign DNA, reducing biosafety concerns and regulatory hurdles. Early applications of viral vectors have demonstrated tangible improvements in crop performance, such as enhanced water-use efficiency in tomato and increased resilience to drought and heat in other crops (Fan et al., 2025). Geminivirus- and tobamovirus-based vectors have been used to transiently deliver CRISPR/Cas9 components, enabling rapid functional characterization of stress-responsive genes and activation of protective pathways in multiple plant species (Yin et al., 2015; Zaidi et al., 2017, 2020; Bhattacharjee et al., 2022; Uranga et al., 2023). Additionally, Tobacco rattle virus (TRV) has been engineered to deliver guide RNAs for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in plants. For instance, a study demonstrated that TRV-mediated delivery of guide RNAs resulted in efficient genome editing in tomato somatic cells, with mutagenesis efficiency reaching up to 65% in leaves and 50% in fruits (Wang et al., 2024). This approach allows for transient and heritable genome modifications without the need for stable transformation.

By leveraging virus-based genome-editing vectors, such as TRV and geminivirus-derived systems, this approach provides a flexible, targeted alternative to conventional breeding and transgenics, accelerating the development of resilient, high-performing crops for sustainable agriculture (Zhang et al., 2024).

3.3 Epigenetic modulation

Viruses can influence plant traits not only through direct infection but also via epigenetic modulation, altering gene activity without changing the DNA sequence itself. These changes are often reversible and can fine-tune traits such as flowering time, growth rate, and stress tolerance (Roossinck, 2015). A key mechanism is RNA interference (RNAi), in which viral infection perturbs small RNA pathways, including microRNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), which play critical roles in regulating plant development and defense. For instance, cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) infection in Arabidopsis was shown to disrupt small RNA balances, shifting flowering regulation and stress responses (Takahashi et al., 2022). Similarly, viral infections can reshape DNA methylation and histone modification patterns, activating or silencing stress-responsive genes (Roossinck, 2011). In some cases, these modifications leave a “stress memory,” priming plants for enhanced resilience against future challenges (Xu et al., 2008; Bhar et al., 2021). Beyond natural infections, this opens exciting biotechnological possibilities. Because viruses can act as temporary switches, researchers have explored deploying engineered viral systems or RNA-based sprays to transiently activate desirable traits (Gentzel et al., 2022). For example, foliar application of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) has been shown to transiently silence specific genes in plants, enabling the activation or deactivation of traits without permanent genetic modification (McRae et al., 2023). Similarly, high-pressure spraying of dsRNAs can trigger the plant RNA interference (RNAi) machinery, leading to transient gene silencing and enhanced disease resistance (Nerva et al., 2022). Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) systems exploit antiviral defense pathways to suppress targeted genes transiently, providing another strategy for reversible trait modulation (Zulfiqar et al., 2023). Beyond RNAi, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) delivered via viral vectors can guide RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM), inducing reversible epigenetic changes that allow plants to dynamically adapt to environmental stresses (Wagh et al., 2025; Papareddy et al., 2020). More recently, synthetic-tasiRNA-based VIGS (syn-tasiR-VIGS) systems have demonstrated that engineered viral vectors can deliver small RNAs to transiently modulate gene expression, highlighting the potential of viruses as tools for dynamic epigenetic reprogramming (Cisneros et al., 2025). Collectively, these approaches illustrate a paradigm shift in which viruses are not merely pathogens but can be harnessed to provide crops with timely, reversible advantages, offering innovative avenues for climate-smart, sustainable agriculture.

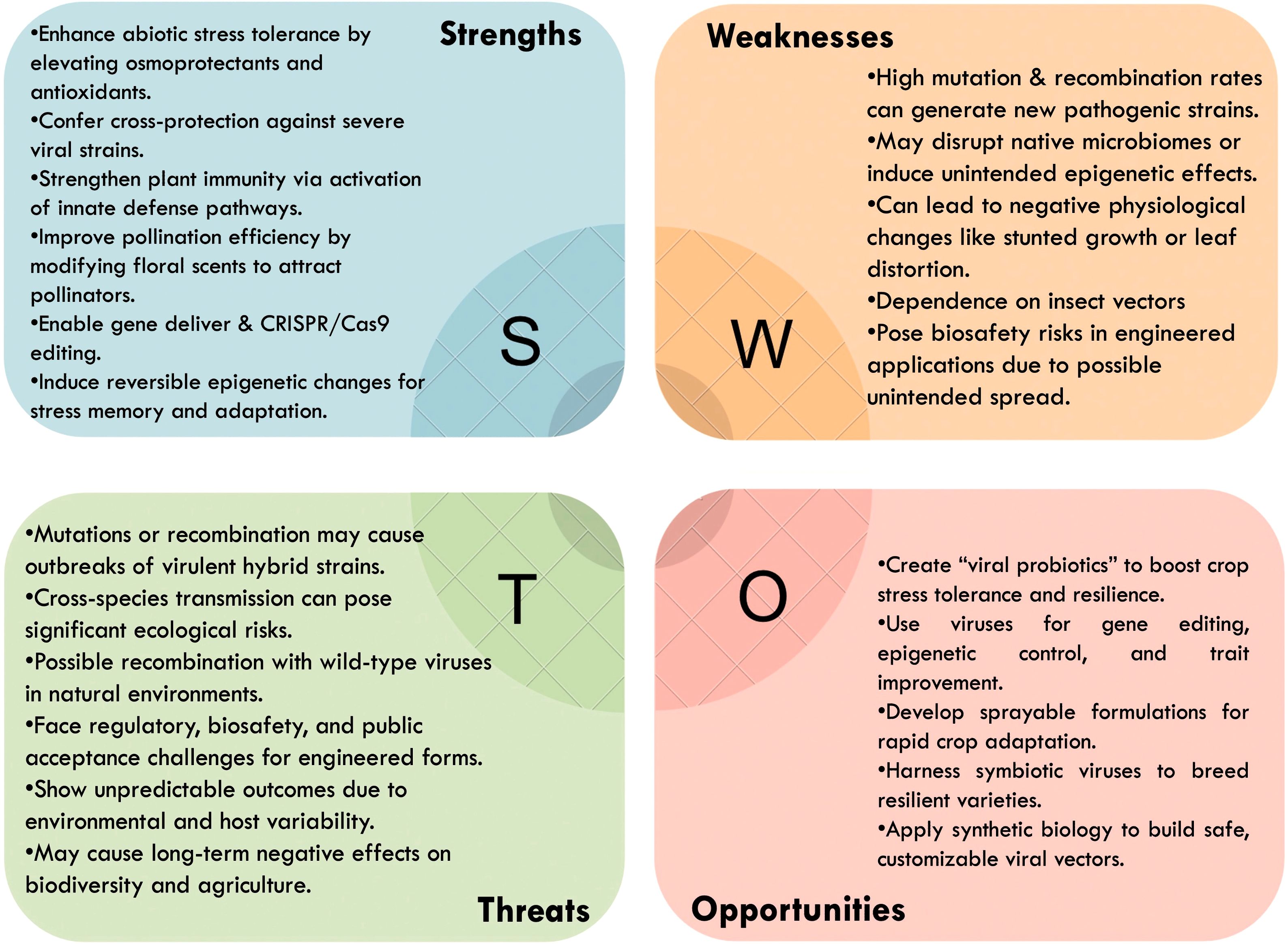

4 Where there’s a boon, there’s a bane

Despite their potential benefits, the use of RNA viruses in plants is not without significant limitations and risks. RNA viruses are inherently prone to high mutation rates and genetic recombination, which can generate novel strains with altered host ranges or pathogenicity, potentially leading to unintended outbreaks (Sanjuán and Domingo-Calap, 2016; Woolhouse et al., 2013). Cross-species transmission is another concern, as viruses that are non-pathogenic in one host may become pathogenic when infecting related or unrelated plant species, posing ecological and agricultural risks (Scholthof et al., 2011; Roossinck, 2015). Engineered or mild strains used for cross-protection or gene delivery could also recombine with wild-type viruses, creating virulent hybrids that threaten crops (Lee and Keremane, 2013; Pechinger et al., 2019). Moreover, RNA viruses can interfere with native plant microbiomes or trigger unintended epigenetic changes that may affect growth or stress responses (Papareddy et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2023). Environmental factors, vector dynamics, and host susceptibility further complicate their deployment in agriculture, making field applications unpredictable.

A deeper understanding of host-virus-environment interactions is needed to ensure consistency and predictability of beneficial effects. Long-term ecological and biosafety assessments will be critical to mitigate risks such as unintended viral recombination or cross-species transmission. While advances in synthetic biology, nanotechnology, and genome editing offer tools to develop customized viral vectors, their successful deployment will require careful regulatory frameworks and acceptance by farmers and stakeholders. To summarize the multifaceted considerations, a SWOT analysis illustrating the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats associated with the use of plant RNA viruses in agriculture has been included and is presented in Figure 1. Therefore, while RNA viruses hold promise as mutualistic partners and biotechnological tools, these inherent challenges must be addressed before practical application in agriculture.

Figure 1. SWOT analysis diagram illustrating the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats associated with the use of plant RNA viruses in agriculture, highlighting their potential as mutualistic agents for stress tolerance and biotechnological applications, alongside the inherent risks and challenges.

5 Future perspectives

The emerging evidence surrounding mutualistic RNA viruses highlights a paradigm shift in plant virology, from perceiving viruses solely as destructive pathogens to recognizing them as potential allies in agriculture. Across stress tolerance engineering, viral vectors for gene delivery, and epigenetic modulation, it is increasingly evident that viruses can be strategically harnessed to enhance resilience, adaptability, and productivity in crops. Looking ahead, the use of mutualistic viruses as “viral probiotics,” bio-safe gene delivery agents, and epigenetic modulators opens a new frontier in crop biotechnology. Viral epigenetic modulation, in particular, offers the exciting possibility of transient, reversible trait enhancement without permanent genetic modification, potentially easing regulatory bottlenecks and public concerns surrounding GMOs. Moreover, the concept of field-deployable viral sprays or formulations that temporarily enhance resilience could redefine crop management practices, allowing crops to be “tuned” to environmental challenges in real time. By bridging natural viral ecology with engineered applications, future research may transform these hidden allies into practical tools for building climate-resilient and food-secure cropping systems.

In conclusion, mutualistic RNA viruses represent an untapped resource in sustainable agriculture, combining ecological adaptability with cutting-edge biotechnology. By bridging natural viral ecology with engineered applications, future research may transform these hidden allies into practical tools for building climate-resilient and food-secure cropping systems.

Author contributions

AR: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BB: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VH: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Al-Hamdani, S., Stoelting, A., and Morsy, M. (2015). Influence of symbiotic interaction between fungus, virus, and tomato plant in combating drought stress. Am. J. Plant Sci. 6, 1633–1640. doi: 10.4236/ajps.2015.610163

Al-Khayri, J. M., Rashmi, R., Surya Ulhas, R., Sudheer, W. N., Banadka, A., Nagella, P., et al. (2023). The role of nanoparticles in response of plants to abiotic stress at physiological, biochemical, and molecular levels. Plants 12, 292. doi: 10.3390/plants12020292

Ando, S., Miyashita, S., and Takahashi, H. (2019). Plant defense systems against cucumber mosaic virus: Lessons learned from CMV–Arabidopsis interactions. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 85, 174–181. doi: 10.1007/s10327-019-00850-4

Augustine, S. M., Tzigos, S., and Snowdon, R. (2023). Heat-killed tobacco mosaic virus mitigates plant abiotic stress symptoms. Microorganisms 11, 87. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11010087

Bhar, A., Chakraborty, A., and Roy, A. (2021). Plant responses to biotic stress: Old memories matter. Plants 11, 84. doi: 10.3390/plants11010084

Bhattacharjee, B., Tiwari, S., Singh, R., and Mansoor, S. (2022). Geminivirus-derived vectors as tools for functional genomics. Front. Microbiol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.799345

Broecker, F. and Moelling, K. (2019). Evolution of immune systems from viruses and transposable elements. Front. Microbiol. 10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00051

Cisneros, A. E., Alarcia, A., Llorens-Gámez, J. J., Puertes, A., Juárez-Molina, M., Primc, A., et al. (2025). Syn-tasiR-VIGS: Virus-based targeted RNAi in plants by synthetic trans-acting small interfering RNAs derived from minimal precursors. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, gkaf183. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaf183

Ellendorff, U., Fradin, E. F., De Jonge, R., and Thomma, B. P. H. J. (2009). RNA silencing is required for Arabidopsis defence against Verticillium wilt disease. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 591–602. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern306

Fan, S., Jia, L., Wu, J., and Zhao, Y. (2025). Harnessing the potential of CRISPR/cas in targeted alfalfa improvement for stress resilience. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 3311. doi: 10.3390/ijms26073311

Gentzel, I. N., Ohlson, E. W., Redinbaugh, M. G., Stewart, L. R., Domier, L. L., Krenz, B., et al. (2022). VIGE: Virus-induced genome editing for improving abiotic and biotic stress traits in plants. Stress Biol. 2, 2. doi: 10.1007/s44154-021-00026-x

Groen, S. C., Jiang, S., Murphy, A. M., Cunniffe, N. J., Westwood, J. H., Davey, M. P., et al. (2016). Virus infection of plants alters pollinator preference: A payback for susceptible hosts? PloS Pathog. 12, e1005790. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005790

Hur, S. (2019). Double-stranded RNA sensors and modulators in innate immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 37, 349–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042718-041356

Khankhum, S., Sela, N., Osorno, J. M., and Valverde, R. A. (2016). RNA-seq analysis of endornavirus-infected vs. endornavirus-free common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) cultivar Black Turtle Soup. Front. Microbiol. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01905

Lee, R. F. and Keremane, M. L. (2013). Mild strain cross protection of tristeza: A review of research to protect against decline on sour orange in Florida. Front. Microbiol. 4. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00259

Leonetti, P., Stuttmann, J., and Pantaleo, V. (2021). Regulation of plant antiviral defense genes via host RNA-silencing mechanisms. Virol. J. 18, 231. doi: 10.1186/s12985-021-01664-3

Licciardello, G., Scuderi, G., Russo, M., Raspudi, S., Caruso, A. G., Catara, A., et al. (2023). Minor variants of Orf1a, p33, and p23 genes of VT strain citrus tristeza virus isolates show symptomless reactions on sour orange and prevent superinfection of severe VT isolates. Viruses 15, 2037. doi: 10.3390/v15102037

Lundstrom, K. (2023). Self-replicating vehicles based on negative strand RNA viruses. Cancer Gene Ther. 30, 771–784. doi: 10.1038/s41417-022-00520-8

Mahmood, M. A., Naqvi, R. Z., Rahman, S. U., Alotaibi, S. S., Nazar, A., Sarwar, M. B., et al. (2023). Plant virus-derived vectors for plant genome engineering. Viruses 15, 531. doi: 10.3390/v15020531

Mandadi, K. K. and Scholthof, K. B. G. (2013). Plant immune responses against viruses: How does a virus cause disease? Plant Cell 25, 1489–1505. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.111658

McRae, A. G., Ahmed, I., Saur, I. M. L., Ellwood, S., Deller, S., Wilson, C. R., et al. (2023). Spray-induced gene silencing to identify powdery mildew gene targets and processes for powdery mildew control. Mol. Plant Pathol. 24, 1168–1178. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13361

Nerva, L., Guida, G., Vallino, M., Luca, E., Chitarra, W., Chiapello, M., et al. (2022). Spray-induced gene silencing targeting a glutathione S-transferase gene confers protection to Nicotiana benthamiana and Brassica juncea against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Cell Environ. 45, 1620–1633. doi: 10.1111/pce.14228

Papareddy, R. K., Palomar, M., Ramesh, S. V., Khraiwesh, B., Choi, H. S., Manavella, P. A., et al. (2020). Chromatin regulates expression of small RNAs to help maintain transposon methylome homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 21, 251. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02173-6

Pechinger, K., Chooi, K. M., MacDiarmid, R. M., Harper, S. J., and Ziebell, H. (2019). A new era for mild strain cross-protection. Viruses 11, 670. doi: 10.3390/v11070670

Prabahar, A., Swaminathan, S., Loganathan, A., and Jegadeesan, R. (2015). Identification of novel inhibitors for tobacco mosaic virus infection in Solanaceae plants. Adv. Bioinf. 2015, 198214. doi: 10.1155/2015/198214

Pumplin, N. and Voinnet, O. (2013). RNA silencing suppression by plant pathogens: Defence, counter-defence and counter-counter-defence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 745–760. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3120

Rattan, U. K., Kumar, S., Kumari, R., Mishra, R., Singh, A., Choudhary, M., et al. (2022). Homeobox 27, a homeodomain transcription factor, confers tolerance to CMV by associating with cucumber mosaic virus 2b protein. Pathogens 11, 788. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11070788

Resour, G., Evol, C., Dos, C., Martins, C., Pereira, L., Silva, A., et al. (2025). Effect of papaya ringspot virus infection in Brazilian Carica papayaaccessions under controlled conditions. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 72, 7223–7233. doi: 10.1007/s10722-025-02383-2

Roossinck, M. J. (2011). The good viruses: Viral mutualistic symbioses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 99–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2491

Roossinck, M. J. (2015). Plants, viruses and the environment: Ecology and mutualism. Virology 479–480, 271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.041

Sanjuán, R. and Domingo-Calap, P. (2016). Mechanisms of viral mutation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 4433–4448. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2299-6

Schmitt, M. J. and Breinig, F. (2002). The viral killer system in yeast: From molecular biology to application. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26, 257–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00614.x

Scholthof, K. B. G., Adkins, S., Czosnek, H., Palukaitis, P., Jacquot, E., Hohn, T., et al. (2011). Top 10 plant viruses in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 938–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00752.x

Shukla, K., Nikita, Singh, P., Gupta, R., Verma, S., Ahmad, A., et al. (2025). Phytohormones and emerging plant growth regulators in tailoring plant immunity against viral infections. Physiologia Plantarum 177, e70171. doi: 10.1111/ppl.70171

Takahashi, H., Tabara, M., Miyashita, S., Sonoda, Y., Yoshida, T., Takahashi, A., et al. (2022). Cucumber mosaic virus infection in Arabidopsis: A conditional mutualistic symbiont? Front. Microbiol. 12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.770925

Tomitaka, Y., Shimomoto, Y., Ryang, B.-S., Hayashi, K., Oki, T., Matsuyama, M., et al. (2024). Development and application of attenuated plant viruses as biological control agents in Japan. Viruses 16, 517. doi: 10.3390/v16040517

Tyagi, H., Rajasubramaniam, S., Rajam, M. V., and Dasgupta, I. (2008). RNA interference in rice against rice tungro bacilliform virus results in its decreased accumulation in inoculated rice plants. Transgenic Res. 17, 897–904. doi: 10.1007/s11248-008-9174-7

Uchida, K., Sakuta, K., Ito, A., Moriyama, H., Sano, T., Suzuki, N., et al. (2021). Two novel endornaviruses co-infecting a Phytophthora pathogen of Asparagus officinalis modulate the developmental stages and fungicide sensitivities of the host oomycete. Front. Microbiol. 12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.633502

Uranga, M., Daròs, J. A., and Brodersen, P. (2023). Tools and targets: The dual role of plant viruses in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. Plant Genome 16, e20220. doi: 10.1002/tpg2.20220

Urayama, S. I., Zhao, Y. J., Kuroki, M., Fukuhara, T., Ohmatsu, T., Komatsu, K., et al. (2024). Greetings from virologists to mycologists: A review outlining viruses that live in fungi. Mycoscience 65, 1–11. doi: 10.47371/mycosci.2024.01

Villa, T. G., Abril, A. G., Sánchez, S., Cortés, P., Álvarez, M., Arús, P., et al. (2021). Animal and human RNA viruses: Genetic variability and ability to overcome vaccines. Arch. Microbiol. 203, 443–464. doi: 10.1007/s00203-020-02034-8

Voloudakis, A. E., Kaldis, A., and Patil, B. L. (2025). RNA-based vaccination of plants for control of viruses. Annu. Rev. Virol. 47, 29–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-091919

Wagh, S. S., Patel, M., Desai, R., Kulkarni, V., Bhatt, P., Sharma, R., et al. (2025). Small RNA and epigenetic control of plant immunity. Plants 5, 47. doi: 10.3390/plants5040047

Wang, Q., Zhang, D., Dai, Y. R., and Liu, C. C. (2024). Efficient tobacco rattle virus-induced gene editing in tomato mediated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Biotechnol. J. 19, e2400204. doi: 10.1002/biot.202400204

Woolhouse, M. E. J., Adair, K., and Brierley, L. (2013). RNA viruses: A case study of the biology of emerging infectious diseases. Microbiol. Spectr. 1, OH–0012-2012. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.OH-0012-2012

Xu, P., Chen, F., Mannas, J. P., et al. (2008). Virus infection improves drought tolerance. New Phytol. 180, 911–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02627.x

Xu, X. J., Zhu, Q., Jiang, S. Y., Li, F., Gao, R., Chen, X., et al. (2021). Development and evaluation of stable sugarcane mosaic virus mild mutants for cross-protection against infection by severe strain. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.788963

Yin, K., Han, T., Liu, G., Chen, T., Wang, Y., Yu, A., et al. (2015). A geminivirus-based guide RNA delivery system for CRISPR/Cas9 mediated plant genome editing. Sci. Rep. 5, 14926. doi: 10.1038/srep14926

Zaidi, S. S. A., Mahas, S., Vanderschuren, H., and Mahfouz, M. M. (2020). Engineering crops of the future: CRISPR approaches to enhance resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses. Genome Biol. 21, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02204-y

Zaidi, S. S. A., Mansoor, S., and Mahfouz, M. M. (2017). Viral vectors for plant genome engineering. Front. Plant Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00539

Zhang, D., Xu, F., Wang, F., Le, L., and Pu, L. (2024). Synthetic biology and artificial intelligence in crop improvement: Engineering resilience and productivity. Plant Commun. 5, 101220. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2024.101220

Zhou, C. and Zhou, Y. (2012). Strategies for viral cross protection in plants. In Methods Mol. Biol. 894, 69–81). doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-882-5_5

Zhu, T., Niu, G., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Li, M., Liu, Q., et al. (2023). Host-mediated RNA editing in viruses. Biol. Direct 18, 34. doi: 10.1186/s13062-023-00428-9

Keywords: RNA viruses, symbiotic relationship, immunity, plant adaptation, agriculture

Citation: Roy A, Bhattacharjee B and Hallan V (2025) Dancing with the enemy: symbiotic relationships between plant RNA viruses and their hosts. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1716996. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1716996

Received: 01 October 2025; Accepted: 10 November 2025; Revised: 31 October 2025;

Published: 27 November 2025.

Edited by:

Sumit Jangra, University of Florida, United StatesReviewed by:

Alireza Golnaraghi, Islamic Azad University, IranRadwa Kamel, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, United States

Xiangru Chen, Guizhou University, China

Pooja Manchanda, Punjab Agricultural University, India

Mario Sánchez-Sánchez, Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, A.C, Mexico

Copyright © 2025 Roy, Bhattacharjee and Hallan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bipasha Bhattacharjee, YmlwYXNoYWJoYXR0YWNoYXJqZWU5MkBnbWFpbC5jb20=; Vipin Hallan, aGFsbGFuQGloYnQucmVzLmlu

Abhisha Roy

Abhisha Roy Bipasha Bhattacharjee

Bipasha Bhattacharjee Vipin Hallan

Vipin Hallan