- 1Graduate School of Bioagricultural Sciences, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan

- 2Department of Horticulture and Food Security, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Nairobi, Kenya

- 3Faculty of Agriculture, Meijo University, Nagoya, Japan

- 4International Center for Research and Education in Agriculture, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan

Crown root (CR) development is a major determinant of rice root system architecture and influences nutrient uptake, tiller number, and grain yield. Although polar auxin transport mediated by PIN proteins is critical for CR formation, the transcriptional regulation of specific PIN members remains unclear. Here, we demonstrate a novel regulation of OsPIN9 mediated by the bZIP transcription factor OUR1/OsbZIP1. Loss of OUR1/OsbZIP1 function significantly promotes CR formation under nutrient-sufficient conditions, and this induction requires upregulation of the auxin efflux carrier OsPIN9, which we identify as a direct target of OUR1/OsbZIP1. Disruption of OsPIN9 mostly abolished the enhanced CR phenotype of the our1 mutant. Spatially adjacent patterns of upregulated OsPIN9 and enhanced auxin signaling were accompanied by the induction of the CR initiation regulators CRL1, CRL5, and OsWOX11, defining an OUR1/OsbZIP1–OsPIN9 module that integrates auxin transport and signaling to regulate CR development in rice.

1 Introduction

Rice is one of the most important cereal crops globally (Fukagawa and Ziska, 2019), serving as a staple food for more than half of the world’s population and providing nearly one-quarter of the global caloric intake (Fitzgerald et al., 2009; Muthayya et al., 2014; Mohidem et al., 2022). Root systems are central to plant growth, as they determine the amount of nutrients and water available, thereby directly impacting yield and underpinning agricultural productivity (Thorup-Kristensen and Kirkegaard, 2016; Lynch, 2019; Tracy et al., 2020, 2023; Holz et al., 2024). The rice root system consists of seminal roots (SR) and postembryonic shoot-borne crown roots (CRs; adventitious roots), both of which give rise to lateral roots (LRs) (Yamauchi et al., 1987; Rebouillat et al., 2009). Among these, CRs are the predominant components of the fibrous root system and play pivotal roles in anchorage, water and nutrient uptake and grain yield (Coudert et al., 2010; Mai et al., 2014; Meng et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021).

CR formation proceeds through defined stages, from founder cell specification to primordium initiation, tissue patterning, vascular connections, and emergence (Itoh et al., 2005). Substantial evidence has established auxin as the central determinant of CR initiation: local auxin gradients at the stem base, notably the innermost ground meristem, where cell dedifferentiation and CR primordium (CRP) formation (Kitomi et al., 2008; Dabravolski and Isayenkov, 2025). Auxin gradients require polar auxin transport (PAT) mediated by the PIN-FORMED 1 (PIN1) efflux carrier and are maintained by endosomal recycling via GNOM (Benková et al., 2003); mutations in CRL4/OsGNOM result in impaired formation of the auxin gradient and inhibition of CR initiation (Geldner et al., 2003; Kitomi et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009). Together with the co-expression of OsPIN1b and CRL4 at the stem base, the defective PAT in crl4 suggests that OsPIN1b-mediated PAT controlled by CRL4/OsGNOM is indispensable for CR initiation in rice (Xu et al., 2005; Kitomi et al., 2008).

Downstream of auxin transport, auxin perception by the TIR1/AFB SCF complex promotes AUX/IAA degradation, releasing ARF transcription factors to activate target genes (Gray et al., 2001; Tiwari et al., 2004; Dharmasiri et al., 2005; Chapman and Estelle, 2009). Among these targets, CRL1/ARL1 (an LBD transcription factor) is indispensable for CR formation, as loss-of-function alleles exhibit severe CR initiation defects (Inukai et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2005). CRL5 encodes an AP2/ERF transcription factor that acts downstream of auxin/ARF to promote CRP initiation while tempering cytokinin responses; crl5 mutants produce fewer CRs. CRL5 overexpression confers cytokinin resistance for CR initiation and promotes the type-A response regulators OsRR1 and OsRR2. Notably, crl1 crl5 double mutants exhibit additive phenotypes, indicating pathway complementarity (Kitomi et al., 2011). Although direct ARF occupancy at the OsWOX11 promoter has not yet been demonstrated, OsWOX11 functions as an auxin-inducible activator of CR development and OsWOX11 transcripts accumulate at the stem base. Oswox11 loss-of-function lines show markedly reduced CR initiation and delayed emergence, while OsWOX11 overexpression drives precocious and ectopic CR formation (Zhao et al., 2009, 2015; Zhang et al., 2018; Geng et al., 2024).

Auxin activity during CR development is further tuned by regulatory modules that interact with cell-cycle control and tissue patterning. The miR156–OsSPL3–OsMADS50 pathway modulates auxin signaling and transport components and reduces CR number when misregulated (Shao et al., 2019). Auxin–cytokinin crosstalk is integrated via OsWOX11 and ERF3 to promote CRP initiation and subsequent growth (Zhao et al., 2009, 2015), whereas OsCKX4 is transcriptionally regulated by OsWOX11 and CRL1 fine-tunes cytokinin levels at CRP sites to maintain hormonal balance (Gao et al., 2014; Geng et al., 2023). Additionally, OsNAC2 acts as an upstream integrator of auxin–cytokinin signaling by directly binding to the promoters of OsARF25 and OsCKX4 (Mao et al., 2020). Collectively, these studies frame CR formation as an auxin-centered process dependent on coordinated transport, signaling, and hormonal crosstalk.

PIN proteins function as auxin efflux carriers and mediate PAT, thereby generating auxin gradients essential for root initiation and patterning (Friml et al., 2002, 2003; Vieten et al., 2005). The rice genome encodes at least 12 PIN family members, many of which exhibit distinct expression domains and functional specializations compared with their Arabidopsis counterparts (Wang et al., 2009; Miyashita et al., 2010). Expression analyses have shown that most OsPIN genes are active in the vascular tissues of the stem base (Wang et al., 2009), directing auxin flow toward the root tip via the mature vasculature, similar to the pattern reported in Arabidopsis (Benková et al., 2003). Functional studies have demonstrated that several OsPIN genes specifically contribute to CR development. For example, the knockdown of OsPIN1 resulted in significant inhibition of CR emergence and development (Xu et al., 2005). Similarly, OsPIN10a regulates CR initiation, underscoring the importance of coordinated auxin efflux at the stem base (Wang et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2012). OsPIN9 is particularly notable as a monocot-specific PIN that is absent in dicots, suggesting a lineage-specific functional innovation (Paponov et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2009; Miyashita et al., 2010). More recently, OsPIN9 was reported to be induced by ammonium and to mediate auxin redistribution in the basal internodes, thereby promoting CR initiation and enhancing tiller formation (Hou et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2022).

The basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor family is highly conserved in plants and integrates hormonal and environmental signals into developmental programs (Jakoby et al., 2002). In Arabidopsis, the bZIP protein HY5 is a central regulator of photomorphogenesis and has been linked to auxin transport and signaling (Cluis et al., 2004). Its rice homolog, OsbZIP1, regulates multiple traits, including flowering time, photomorphogenesis, nutrient uptake, root development and grain yield (Chai et al., 2021; Hasegawa et al., 2021; Bhatnagar et al., 2023; Tanaka et al., 2024; Xinli et al., 2024; Xiong et al., 2024). Under low nitrogen and phosphorus conditions, enhanced root length has been reported in 88n, a loss-of-function mutant of OsbZIP1, along with improved yield, driven by increased Pi uptake and nitrogen use efficiency (Tanaka et al., 2024). The vig1a allele greatly enhanced seedling vigor, chilling tolerance, and grain production. The specific mutation of vig1a disrupts the interaction between OsbZIP1 and OsbZIP18, another HY5 homolog, suggesting that OsbZIP1 functions cooperatively with OsbZIP18 in diverse crucial biological processes that determine seedling establishment, chilling tolerance, and grain yield (Xiong et al., 2024). Notably, multiple OsbZIP1 alleles are associated with robust root systems, suggesting that OsbZIP1 exerts a conserved effect on root architecture (Hasegawa et al., 2021, 2022; Tanaka et al., 2024; Xiong et al., 2024). Consistent with this view, the loss-of-function our1 allele regulates root development via altered auxin signaling (Hasegawa et al., 2021). However, the downstream targets of OUR1/OsbZIP1 during root development remain unclear.

To address this gap, this study investigated the mechanism by which OUR1/OsbZIP1 directly and negatively regulates OsPIN9 to control CR development via an auxin-dependent pathway. Loss of OUR1/OsbZIP1 function enhances CR formation under nutrient-sufficient conditions, at the stem base, upregulated OsPIN9 expression increased auxin transport toward the innermost ground meristem, promoting auxin signaling and activating CR regulators. Genetic and molecular evidence establishes an OUR1/OsbZIP1–OsPIN9 module that integrates auxin transport and signal activation to regulate CR formation in rice.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Construction of transgenic plants

The pOsPIN9-OUR1cis promoter-edited line and OsPIN9 mutant were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system (Mikami et al., 2015). Guide RNAs targeting OUR1/OsbZIP1 binding site in OsPIN9 promoter and OsPIN9 exon 1 were designed using the CRISPOR-assisted website (Haeussler et al., 2016) and cloned into pZH_OsU6gRNA_MMCas9 vector (Mikami et al., 2015) to generate the pOsPIN9-OUR1cis-CRI and OsPIN9-CRI constructs, respectively. The DR5:NLS-3×Venus were constructed as previously described (Lucob-Agustin et al., 2020). To generate pOsPIN9:NLS-3×Venus construct, a 3 kb genomic fragment upstream of the OsPIN9 translation start codon (ATG defined as +1) was PCR-amplified from wild-type ‘Kimmaze’ genomic DNA and cloned it into the pGWB1 vector (Nakagawa et al., 2007). To construct p35s:OUR1-GFP, the OUR1-GFP fragment was amplified from the ProOUR1:OUR1-GFP construct made in the previous study (Hasegawa et al., 2021), and cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO® vector and subsequently transferred into the pGWB502Ω vector using the Gateway LR reaction (Nakamura et al., 2009). All primers used in this study were listed in Supplementary Table 1.

The generated fusion constructs were introduced into the EHA 105 strain of Agrobacterium tumefaciens via electroporation. Subsequently, constructs were transformed into plants via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (Hiei et al., 1994; Ozawa, 2009). Immature embryos harvested from 10 to 14 days after flowering were infected by Agrobacterium carrying the respective constructs. After 2 days of co-cultivation, infected immature embryos were transferred to a fresh resting medium containing 400 mg/L carbenicillin disodium salt (Nakarai, Kyoto, Japan) to remove Agrobacterium. Following this, Hygromycin-resistant calli were selected over 4 weeks on a selection medium containing 400 mg/L carbenicillin disodium salt and hygromycin 30 mg/L (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan). Proliferating calli were then transferred to a fresh pre-regeneration medium containing 200 mg/L carbenicillin disodium salt and hygromycin 40 mg/L. After 8 days of culture, these calli were transferred to a fresh regeneration medium containing 30 mg/L hygromycin B and cultured for 2 weeks.

2.2 Plant material and growth conditions

Oryza sativa cv. Kimmaze (KM) was the wild-type (WT) for the our1 mutant (Hasegawa et al., 2021). The pOsPIN9-OUR1cis promoter-edited line was obtained by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutation of the OUR1/OsbZIP1 binding site cluster in the OsPIN9 promoter in the WT background. The pin9 our1 double mutant was generated by knocking out the OsPIN9 gene in the our1 mutant using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. DR5:NLS-3×Venus and pOsPIN9:NLS-3×Venus reporter constructs were introduced into the WT and our1 mutants. Because KM is less amenable to Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, the p35s:OUR1-GFP construct was introduced into the transformable cultivar Taichung65 (Yara et al., 2001) for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis.

Rice seeds were pre-germinated in water mixed with fungicide (0.25% [w/v] benomyl benlate; Sumitomo Chemical Co.) and placed in a growth chamber (MLR-351; Sanyo) at 28 °C with continuous light for 24 hours, followed by rinsing and soaking for 48 hours in tap water filtered using a water purifier (MX600; TORAY Industries) (Kawai et al., 2022b). Germinated seeds were transferred onto floating plastic nets in a 9-L black plastic box (32 cm height × 19 cm length × 19 cm width) filled with 10% nutrient solution (Colmer, 2003), which was replaced every 7 days. The full-strength nutrient solution contained (mol m-³): 3.95 K+, 1.50 Ca²+, 0.40 Mg²+, 0.625 NH4+, 4.375 NO3-, 1.90 SO4²-, 0.20 H2PO4-, 0.20 Na+, and 0.10 H4SiO4. Micronutrients (mmol m-³) were 50.0 Cl, 25.0 B, 2.0 Mn, 2.0 Zn, 1.0 Ni, 0.5 Cu, 0.5 Mo, and 50.0 Fe-EDTA. The solution also contained 2.5 mol m-³ MES, and the pH was adjusted to 6.5 with KOH, giving a final K+ concentration of 5.6 mol m-³. To assess nitrogen-form availability in the WT and our1 mutant, we applied three adjusted nutrient solutions: complete (+Nut), ammonium-only (−NO3-), and nitrate-only (−NH4+). Solutions were replaced weekly and detailed compositions are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

To examine the responses to nutrient availability, germinated seedlings were first grown in filtered water for 7 days. The plants of each line were then divided into two groups: one group was continuously maintained in filtered water for 14 days and the other was transferred to a nutrient solution for 21 days. For the selected transgenic lines, seedlings were transferred to a 10% nutrient solution and cultivated in 9-L boxes with aeration to promote growth. The later-stage T0 plants were grown to maturity in a controlled greenhouse environment, and T1 seeds were harvested from individual T0 lines for subsequent analyses.

2.3 Electrophoresis mobility shift assay

The coding sequence of OUR1/OsbZIP1, codon-optimized for Escherichia coli usage, was synthesized (Eurofins, Japan) and cloned into the pMAL-c2 vector (New England Biolabs) for fusion with maltose-binding protein. The construct was introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3) and the recombinant proteins were expressed and purified according to the procedure described in a previous study (Kojima et al., 2010). To prepare DNA probes, 60 bp oligonucleotides were labeled with Cy5 fluorescent dye using a Klenow fragment (TaKaRa Bio, Japan) and purified on a column (NuclcoSpine Gel and PCR Clean-up, Macherey-Nagel, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA-binding reaction was performed at 4°C for 30 min in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (-) containing 1 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol, 25.3 nM probe, and 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 μM recombinant OUR1/OsbZIP1-DB proteins. The reaction mixtures were subjected to EMSA with 6% polyacrylamide gels in 0.5 x TBE buffer at 4°C. Cy5-labeled probes were analyzed using a Typhoon FLA9000 (GE Healthcare, USA) (Kawai et al., 2022a).

2.4 ChIP and qPCR analysis

ChIP was performed as previously described with minor modifications (Yamaguchi et al., 2014). Approximately 2 g of fresh root tissue from 4-day-old p35s: OUR1-GFP T1 seedlings was cross-linked with 1% (v/v) formaldehyde under vacuum for 10 min at room temperature, and the reaction was quenched with 0.125 M glycine for 5 min. The tissues were washed three times with cold PBS and ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen. Chromatin was isolated using lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)] and sonicated to shear DNA to an average length of 200–500 bp using a Bioruptor sonicator (Diagenode) with 5 cycles of 10s on/30s off. After centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was diluted 10-fold with ChIP dilution buffer [16.7 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 167 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM EDTA, 0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100] and precleared with Protein A/G agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h at 4°C. Immunoprecipitation was performed with 5 μg anti-GFP antibody overnight at 4°C with gentle agitation. Antibody-bound chromatin complexes were pulled down using Protein A/G agarose beads for 2 h, followed by sequential washes with low-salt buffers, high-salt buffers, LiCl buffers, and TE buffers. Chromatin was eluted with elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3) and reverse-crosslinked at 65°C overnight. DNA was purified using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen). qPCR was performed using SYBR Green master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and specific primers targeting different sites in the promoter region of OsPIN9 on the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Life Technologies). Fold enrichment was calculated relative to the input DNA using the % input method. The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

2.5 Expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the stem bases of the WT, our1 mutant, and T1 pin9 our1 double-mutant seedlings using a NucleoSpin RNA Plant Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using the One-Step SYBR PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit II (Perfect Real Time; Takara Bio) and StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR (Life Technologies). The expression of each gene was normalized to that of UBQ5 (Os03g0234200), which was used as an internal control. The primer sequences used for qRT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

2.6 Measurement of root system architecture

The number of emerged CRs and tillers in the WT, our1 mutant, and T1 pin9 our1 double mutant seedlings grown under nutrient-deficient or nutrient-sufficient conditions was manually counted at defined time points. To determine the number of CRPs, stem bases from WT, our1, and T1 pin9 our1 double mutants were embedded in 6% (w/v) INA agar and cross-sectioned into 150 μm-thick slices (DYK-1000N: Dosaka EM Co.). Sections were arranged sequentially, observed, and imaged with a Zeiss microscope using the Labscope software (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Furthermore, to avoid double counting, CRPs that appeared in consecutive sections with overlapping positions and morphologies were considered as a single primordium.

2.7 Histological analysis

To observe DR5 reporter activity (DR5:NLS-3×Venus) and OsPIN9 promoter activity (pOsPIN9:NLS-3×Venus) in the WT and our1 mutants, stem bases were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS under vacuum for 1h, repeated twice. The samples were then washed with PBS for 30 min. The fixed samples were cross-sectioned into 150 μm-thick slices as described above and then cleared with TOMEI-I to visualize expression (Hasegawa et al., 2016). The sections were examined under a laser scanning microscope (FV3000; Olympus). Venus fluorescence was captured at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and detected at 510–530 nm, whereas tissue autofluorescence was captured at an excitation wavelength of 405 nm and detected at 450–470 nm.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Differences in the morphological characteristics and gene expression between groups were compared using a two-tailed Student’s t-test or Tukey’s multiple-comparison test using GraphPad Prism.

3 Results

3.1 our1 mutant shows enhanced CR formation under nutrient-sufficient conditions

Consistent with a previous study of the root system suggesting that the our1 mutation represses CR formation through restricting auxin signaling (Hasegawa et al., 2021), in filtered water, which is nutrient-deficient, both the WT and our1 mutant exhibited only a modest increase in CR number as they grew, with the our1 mutant consistently producing fewer CRs than the WT throughout the 21 days after sowing (Figures 1A, B, E). However, after 7-day-old seedlings were transferred to a nutrient solution, we found that the our1 mutant exhibited a significantly enhanced CR number compared to the WT (Figures 1C–E). Likewise, tiller number increased in the our1 mutant relative to that in the WT (Figures 2A, B). These results indicate the our1 mutant is more responsive to nutrient availability, displaying strongly enhanced CR formation and increased tiller numbers under nutrient-sufficient conditions. Across nitrogen-form treatments, the our1 mutant reached similarly high CR numbers in the complete nutrient solution supplying both NH4+ and NO3- and the ammonium-only complete nutrient solution (NH4+ as the sole nitrogen source), whereas the nitrate-only complete nutrient solution (NO3- as the sole nitrogen source), produced significantly fewer CRs than either condition, although still more than filtered water (Supplementary Figure 1). Taken together, these patterns suggest that ammonium availability is the principal driver of the enhanced CR formation in the our1 mutant under nutrient-sufficient conditions.

Figure 1. Enhanced CR formation in the our1 mutant under nutrient-sufficient conditions. (A, B) -Nut (filtered water). 7-day-old seedlings were transferred to -Nut and imaged 7 and 14 days after transfer (14 and 21 DAS): WT (A) and our1 mutant (B). Scale bars = 10 cm. (C, D) +Nut (nutrient solution). 7-day-old seedlings were transferred to +Nut and imaged at 14 and 21 DAS as in (A, B): WT (C) and our1 mutant (D). Scale bars = 10 cm. (E) Quantification of CR number corresponding to (A–D) for the WT and our1 mutant under -Nut and +Nut conditions. Seedlings were transferred at 7 DAS; CR numbers were recorded at 7 DAS (pre-transfer), 14 DAS, and 21 DAS. Bars show mean ± SD (n = 8 plants per genotype per time point). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among groups (two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, P < 0.05). (F) Relative expression of OsPIN9 at the stem base of the WT and our1 mutant under -Nut and +Nut conditions. Values represent mean ± SD (n = 3 technical replicates, repeated with two independent biological replicates). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among groups (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, P < 0.05). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

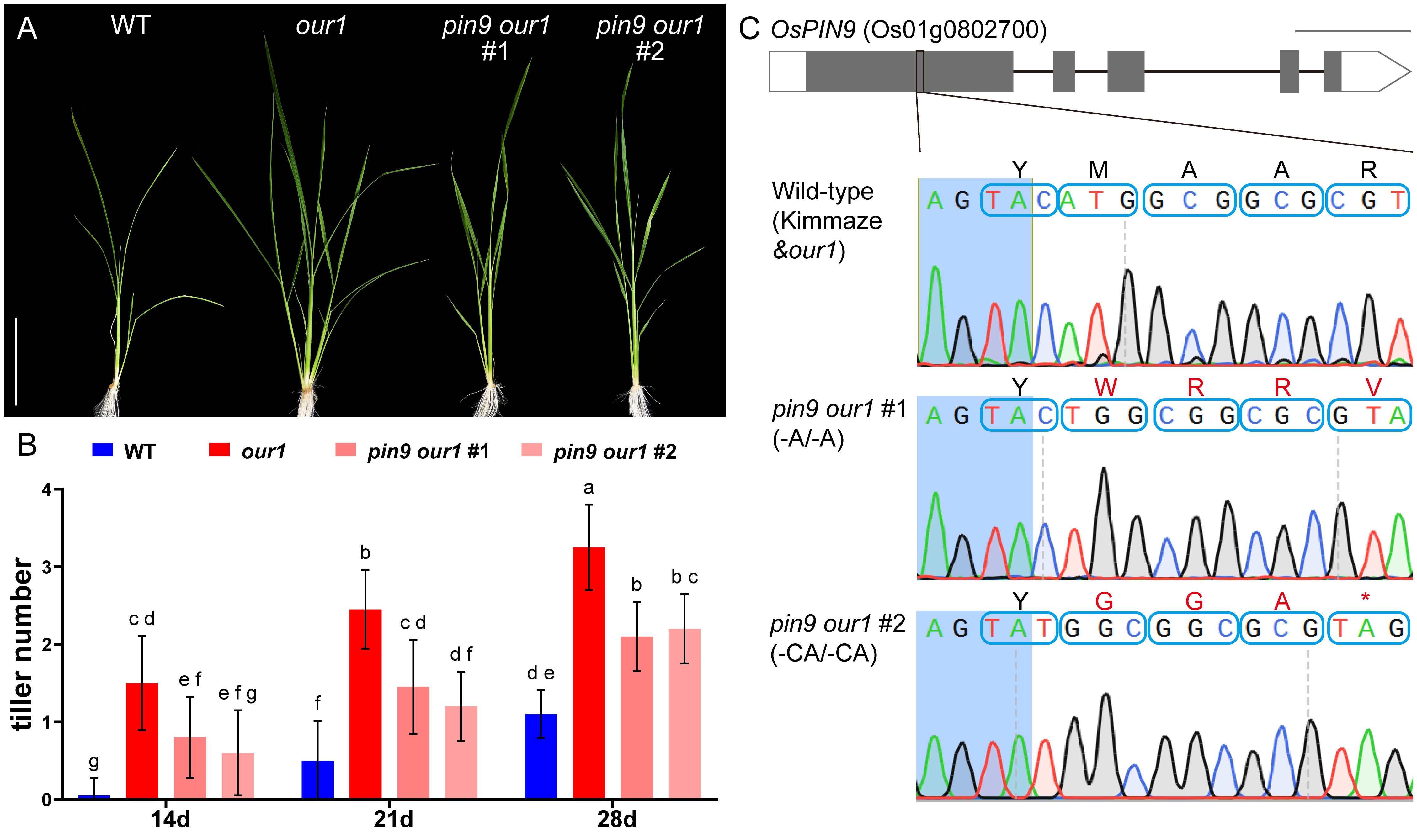

Figure 2. Tiller formation in the WT, our1 mutant, and lines with different mutation of OsPIN9 in the our1 mutant. (A) WT, our1, and T1 pin9 our1 lines grown under +Nut conditions and imaged at 21DAS. Scale bar = 10 cm. (B) Tiller numbers of WT, our1, and T1 pin9 our1 lines counted at the 14, 21, 28 DAS under +Nut conditions. Bars show mean ± SD (n = 20 plants per genotype per time point, T1 pin9 our1 #2, n = 5). Different lowercase letters denote significant differences among genotypes (two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, P < 0.05). Error bars were truncated at zero because tiller counts cannot be negative. (C) Genotypes of T1 lines with different mutations of OsPIN9 in the our1 mutant background. Structure of the OsPIN9 gene (Os01g0802700). Gray and white boxes indicate exons and untranslated regions, respectively. Blue boxes display nucleotide triplets (codons), and the corresponding amino acids are shown above. Scale bars = 500 bp.

3.2 OsPIN9 is a potential contributor for enhanced CR formation in the our1 mutant

CR initiation at the stem base requires a localized auxin maximum that is established by polar auxin transport (Kitomi et al., 2008; Dabravolski and Isayenkov, 2025), which is mainly regulated by PIN auxin efflux carriers (Friml et al., 2002, 2003; Vieten et al., 2005). OsPIN9, one of the PIN carriers, stands out as ammonium-inducible and its overexpression increased CR and tiller numbers (Hou et al., 2021). Because the phenotype of the our1 mutant under nutrient-sufficient, especially ammonium-rich, conditions resembled that of OsPIN9 overexpression lines (Hou et al., 2021), we hypothesized that OsPIN9 is upregulated in the our1 mutant and contributes to enhanced CR formation and increased tiller number. qRT-PCR analysis using the stem base revealed that the our1 mutant exhibited significantly higher OsPIN9 expression levels than the WT under both nutrient-deficient and -sufficient conditions (Figure 1F). These results suggested the repressive role of OUR1/OsbZIP1 on OsPIN9 and support a model in which derepression of OsPIN9—amplified by nutrient stimulation—contributes to enhanced CR formation and increased tiller number in the our1 mutant. A survey of PIN family expression in both WT and our1 mutant showed that, besides the strongest upregulation of OsPIN9, OsPIN8, OsPIN10a, and OsPIN10b were modestly upregulated in the our1 mutant, whereas most other members were unchanged or undetectable in this tissue (Supplementary Figure 2).

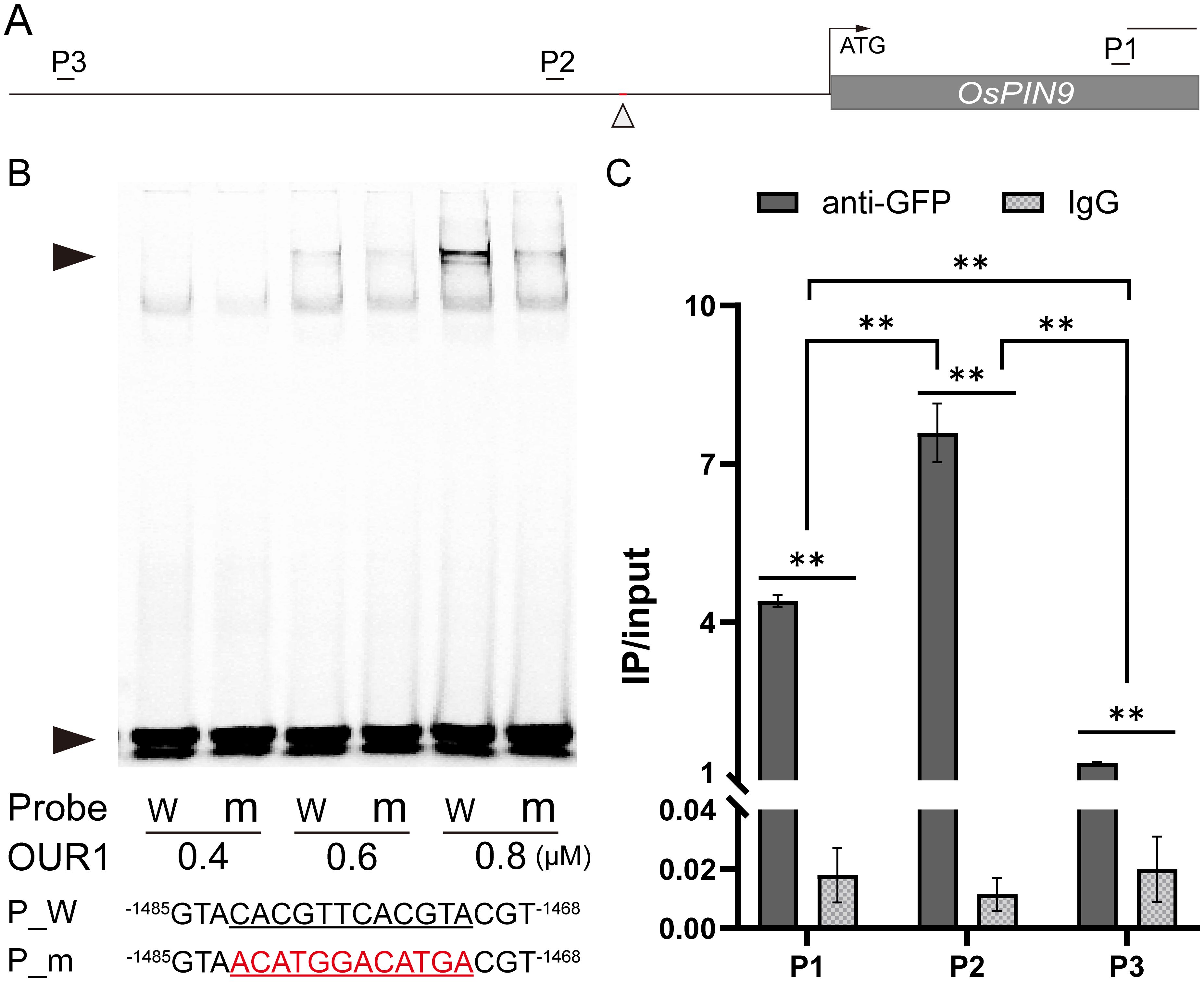

3.3 OUR1/OsbZIP1 binds to the OsPIN9 promoter region

The bZIP transcription factor OsbZIP1 preferentially binds to cis-elements containing an ACGT core sequence, such as the G-box (CACGTG), and related variants in the promoters of target genes (Izawa et al., 1993; Foster et al., 1994; Chai et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2024). Because OsbZIP1 lacks a canonical activation domain and negatively regulates downstream targets (Bhatnagar et al., 2023; Chai et al., 2021; Xinli et al., 2024), we hypothesized that OUR1/OsbZIP1 repress OsPIN9 by directly binding its promoter. In the OsPIN9 promoter region, we identified a potential bZIP1 binding site consisting of two tandem motifs (CACGTTCACGTA) (Figure 3A). EMSA revealed that OUR1/OsbZIP1 bound to the probe containing the cis-element, as indicated by clear shifts at 0.6 and 0.8 μM protein concentrations, whereas binding was markedly reduced when the motif was mutated (Figure 3B). ChIP–qPCR showed significant enrichment of the OsPIN9 promoter fragment near this site (Figure 3C), confirming OUR1/OsbZIP1 binding in vivo. In the promoter-edited line carrying a 25 bp deletion that disrupts the OUR1/OsbZIP1 binding site cluster within the OsPIN9 promoter, OsPIN9 transcript levels were significantly higher than in WT (Supplementary Figure 3), supporting that OUR1/OsbZIP1 acts as a repressor of OsPIN9. Taken together, these results demonstrate that OUR1/OsbZIP1 directly targets the OsPIN9 promoter both in vitro and in vivo, thereby functioning as a negative regulator of OsPIN9 transcription.

Figure 3. OUR1/OsbZIP1 binds to the OsPIN9 promoter region. (A) Schematic of the OsPIN9 locus, showing the upstream promoter, gene region (gray box). Upward arrowheads indicate the putative OUR1/OsbZIP1 binding site tested by electrophoresis mobility shift assay (EMSA), while short line mark primer sites used chromatin immunoprecipitation-qPCR (ChIP–qPCR) primer positions. Scale bar = 500 bp. (B) EMSA demonstrating binding of OUR1/OsbZIP1 to Cy5-labeled probes containing WT or mutated sequences in the OsPIN9 promoter region. Upper and lower arrowheads indicate the shifted bands and free probes, respectively. (Lower) Probes sequences; underlined bases denote core motif, and red bases indicate mutations. Superscripted numbers refer to positions relative to the OsPIN9 translation start site (+1). Full-length sequences of probes are shown in Supplementary Table 1. (C) ChIP–qPCR of the OsPIN9 promoter in T1 seedlings in the WT background expressing p35s:OUR1-GFP. Cross-linked chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibody. Normal IgG serves as a negative control. Values represent mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates), reported as the percentage of input DNA. Asterisks denote significant differences between genotypes (**P < 0.01; two-tailed Student’s t test). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

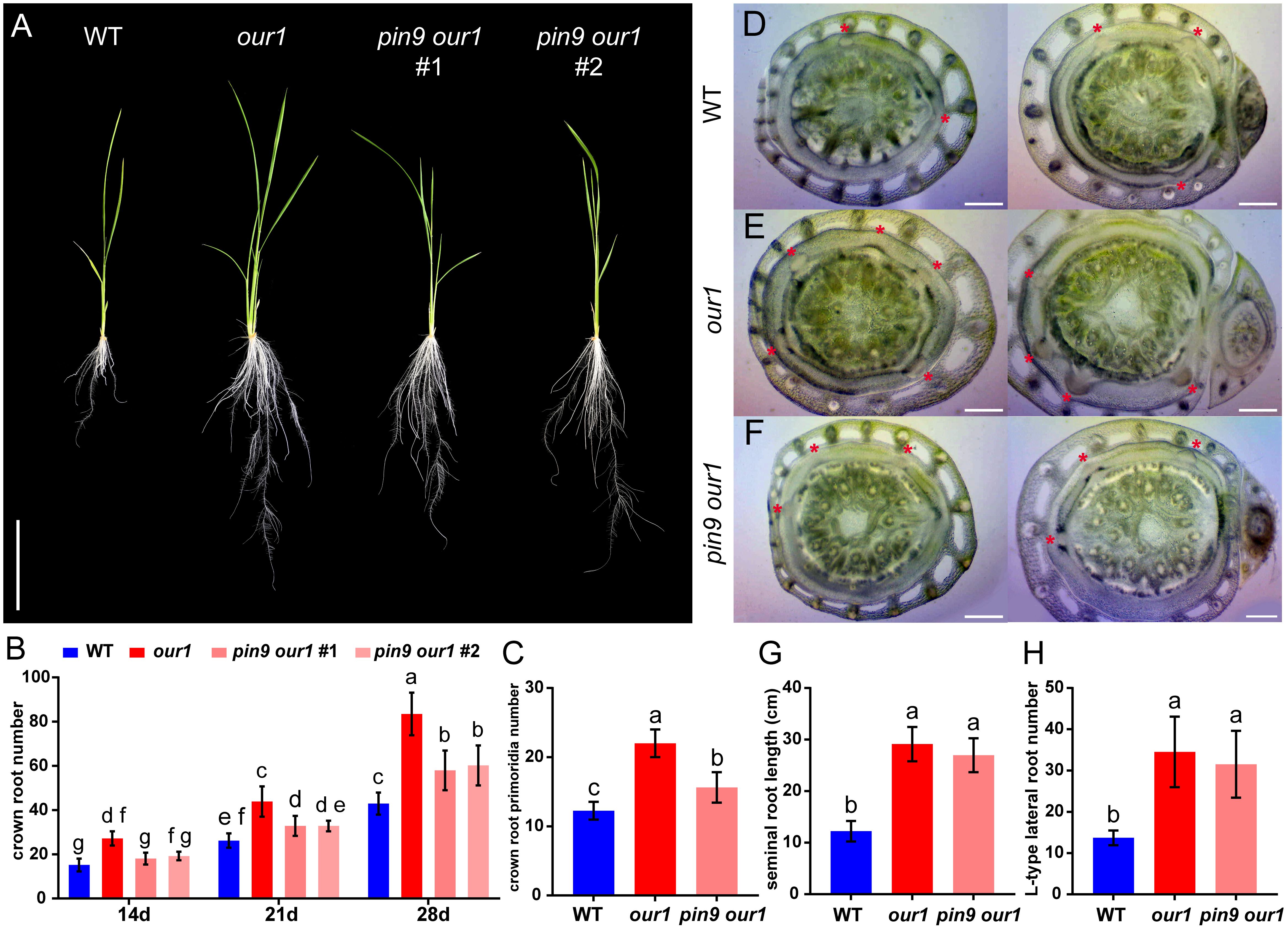

3.4 Upregulated OsPIN9 is required for enhanced CR formation in the our1 mutant

To confirm whether OsPIN9 contributes to the enhanced CR phenotype of the our1 mutant, we generated OsPIN9 knockout lines in the our1 mutant background using CRISPR/Cas9, hereafter referred to as pin9 our1 double mutants (Figure 2C). Phenotypic analysis of T1 seedlings cultivated under nutrient-sufficient conditions revealed that the increased CR and tiller number in the our1 mutant were significantly abolished in the pin9 our1 double mutants (Figures 2A, B, 4A, B), indicating that OsPIN9 upregulation is required for enhanced CR formation. To confirm whether this effect was attributable to CR initiation, we examined stem base cross-sections to quantify CRP. Compared with the our1 mutant, both the WT and pin9 our1 double mutant displayed significantly lower CRP levels (Figures 4C-F), suggesting that OsPIN9 promotes CR formation primarily by enhancing CRP initiation. Furthermore, the pin9 our1 double mutant retained a modest increase in emerged CRs and CRPs compared to the WT (Figures 4B, C), suggesting the involvement of OsPIN9-independent pathways that contribute to the enhanced CR phenotype of the our1 mutant.

Figure 4. Upregulated OsPIN9 promotes CR formation in the our1 mutant. (A) 14-day-old seedlings of the WT, our1 mutant, and T1 pin9 our1 lines grown under +Nut condition. Scale bar = 10 cm. (B) Time course of emerged CRs in the WT, our1, and T1 pin9 our1 lines grown under +Nut conditions at 14, 21, and 28 DAS. (C) CRP number of 14-day-old WT, our1 mutant, and T1 pin9 our1 #1 grown under +Nut condition. (D-F) Cross sections of the stem base of the 14-day-old WT, our1, and T1 pin9 our1 double mutant #1 grown under +Nut conditions. Asterisks mark CRP. Scale bars = 0.5 mm. (G, H) seminal root length (G) and L-type lateral root number (H) of 14-day-old WT, our1, and T1 pin9 our1 #1 grown under +Nut condition. Data presentation, statistics, and sample sizes: Bars show mean ± SD. (B) Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison test. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among genotype–time groups (P < 0.05). (C, G, H) One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison test; different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between genotypes (P < 0.05). Sample sizes: (B) n = 20 plants per genotype; T1 pin9 our1 #2, n = 5 (C) n = 8 per genotype; (G, H) n = 20 per genotype.

Consistent with the previous characterization of the our1 mutant, including elongated SR and increased L-type LR formation (Hasegawa et al., 2021), we investigated whether OsPIN9 also underlies these traits. Despite OsPIN9 being upregulated in the our1 mutant even under nutrient-deficient conditions, loss of OsPIN9 did not significantly affect SR length or L-type LR number in the our1 mutant background (Figures 4G, H), indicating that upregulated OsPIN9 in the our1 mutant specifically induces CR formation but does not promote SR elongation or L-type LR formation.

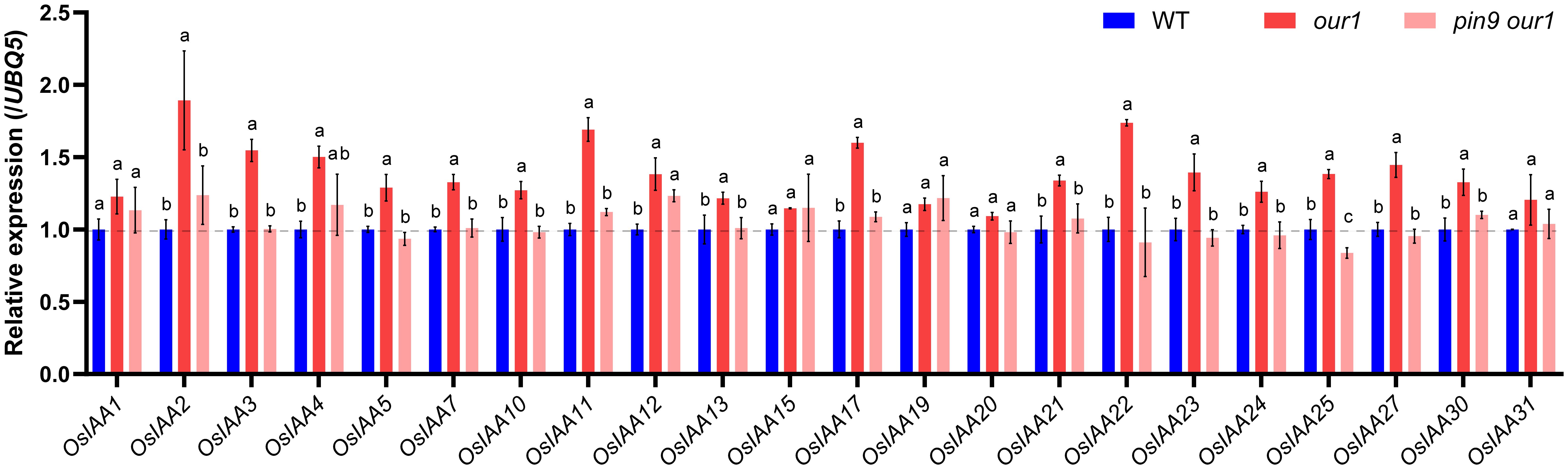

3.5 Upregulated OsPIN9 enhances auxin signaling at the stem base

Because OsPIN9 encodes an auxin efflux carrier, we hypothesized that upregulated OsPIN9 enhances auxin signaling at the stem base in the our1 mutant. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the expression of early auxin-responsive Aux/IAA genes at the stem base. Among the 31 Aux/IAA members in rice, 22 were selected based on their relatively high expression in the stems (Jain et al., 2006; Sato et al., 2013). Most genes were significantly upregulated in the our1 mutant, with particularly strong increases in OsIAA2, OsIAA11, OsIAA17, OsIAA22, which returned to the near-WT baseline in the pin9 our1 double mutant (Figure 5), indicating that enhanced auxin signaling in the our1 mutant is largely mediated by OsPIN9 upregulation.

Figure 5. Expression of AUX/IAA genes at the stem base. Relative expression of 22 AUX/IAA genes at the stem base of the WT, our1, and T1 pin9 our1 #1 seedlings. Expression values were normalized to UBQ5 (WT set to 1). Bars represent the mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). For each gene, different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among genotypes (one-way ANOVA within genes, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, P < 0.05). The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

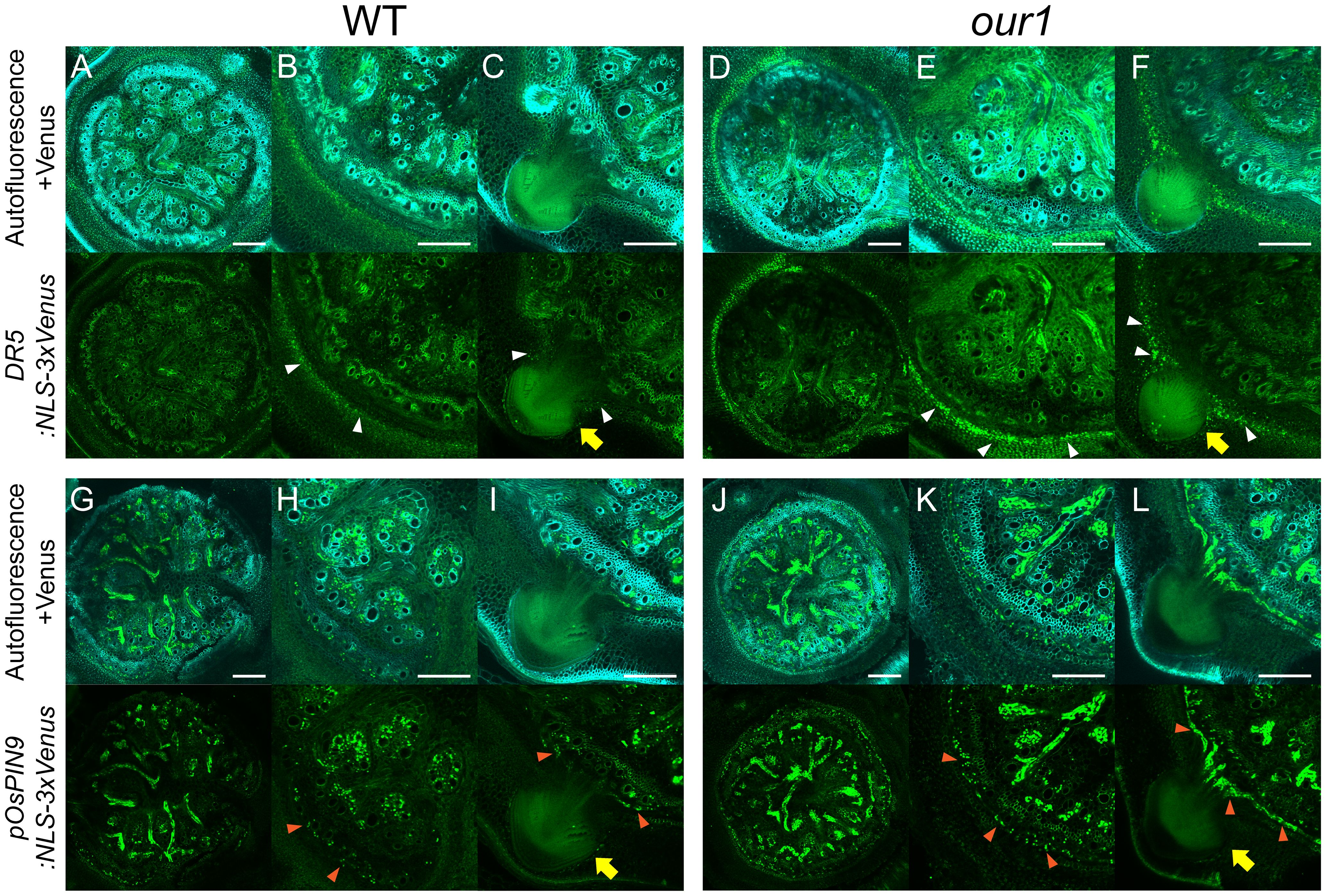

To further visualize how OsPIN9 upregulation enhances auxin signaling at the stem base, we examined the activity of the synthetic auxin-responsive reporter DR5:NLS-3×Venus and the native OsPIN9 promoter reporter (pOsPIN9:NLS-3×Venus) in stem base cross sections. Compared to the WT, DR5 reporter activity was strongly increased in the innermost ground meristem, where CRP initiation occurs in the our1 mutant (Figures 6A–F). Consistently, pOsPIN9 reporter lines showed upregulated OsPIN9 expression in the peripheral cylinder of vascular bundles, which was spatially adjacent to the enhanced auxin signaling in the innermost ground meristem (Figures 6G–L). Together, these observations support a model in which OsPIN9-dependent efflux transports auxins from the peripheral cylinder of the vascular bundles to the ground meristem to further promote CRP initiation in the our1 mutant.

Figure 6. Patterns of auxin signaling and OsPIN9 expression at the stem base. (A–F) Distribution of auxin signaling under +Nut conditions. Cross-sections expressing the DR5:NLS-3×Venus reporter are shown for WT (A–C) and our1 (D–F). Close-up views showing regions without (B, E) and with CRP (C, F). Venus fluorescence (green dots) denotes the DR5-driven auxin response, and autofluorescence is visible in the background. White arrowheads indicate localized auxin signaling, and yellow arrows indicate CRP. Scale bars = 200 µm. (G–L) Spatial pattern of OsPIN9 promoter activity under +Nut conditions. Cross-sections expressing the pOsPIN9:NLS-3×Venus reporter are shown for WT (G–I) and our1 (J–L). Close-up views show regions without CRP (H, K) or CRP (I, L). Venus fluorescence (green dots) denotes pOsPIN9-driven signal, and autofluorescence is visible in the background. Orange arrowheads indicate localized OsPIN9 expression and yellow arrows indicate CRP expression. Scale bars = 200 µm.

3.6 Upregulated OsPIN9 activates genes associated with CR formation

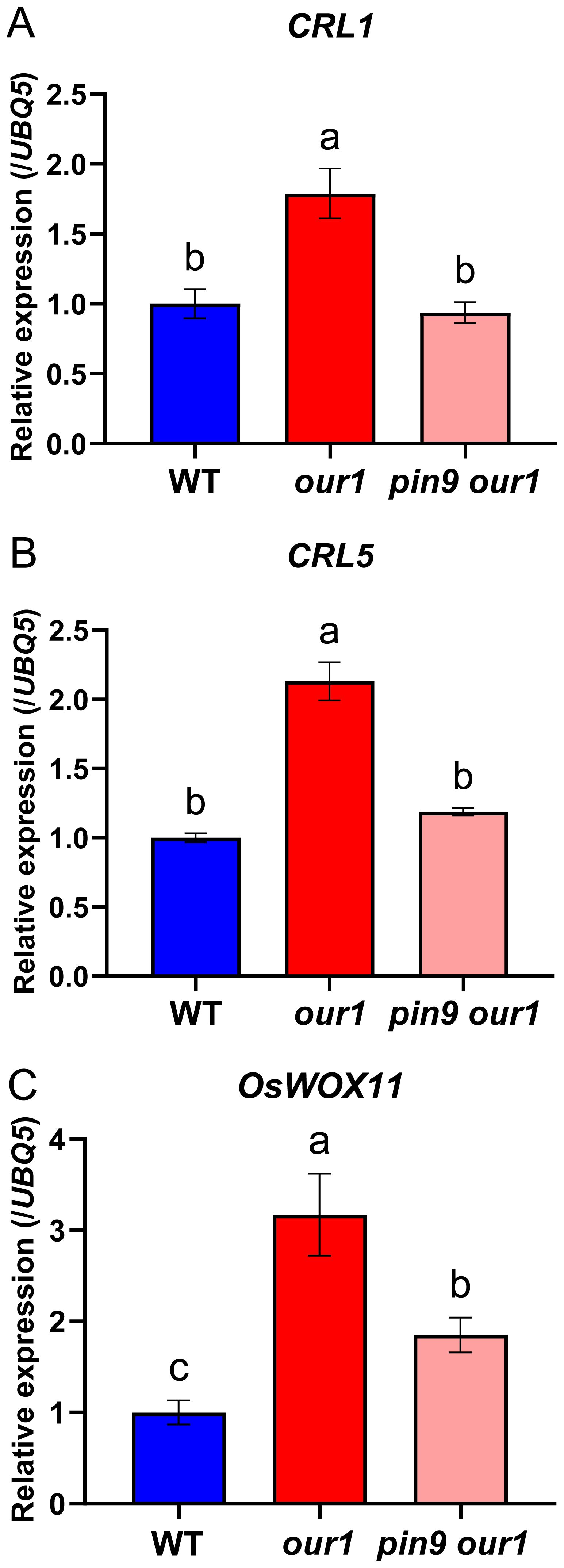

Several auxin-inducible transcription factors, such as CRL1, CRL5, and OsWOX11, have been identified as key regulators of CR initiation and emergence (Inukai et al., 2005; Kitomi et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2018). Under filtered water, transcript levels of CRL1, CRL5, and OsWOX11 were downregulated in the our1 mutant than in WT at the stem base (Supplementary Figure 4), consistent with restricted auxin signaling in the our1 mutant background (Hasegawa et al., 2021). Under nutrient solution, CRL1, CRL5, and OsWOX11 were upregulated in the our1 mutant compared to the WT, whereas their induction was markedly reduced in the pin9 our1 double mutant (Figures 7A–C). Collectively, these results indicate that upregulated OsPIN9 enhances auxin signaling at the stem base, leading to the activation of CR-related transcriptional regulators. Thus, the OUR1/OsbZIP1–OsPIN9 regulatory module promotes CR formation in rice via an auxin-dependent pathway.

Figure 7. Auxin-responsive CR regulators are upregulated at the stem base in the our1 mutant and depend on OsPIN9. (A–C) Relative expression levels of CRL1 (A), CRL5 (B), and OsWOX11 (C) at the stem base in the WT, our1, and T1 pin9 our1 double mutant #1 seedlings under +Nut conditions for 14d. Expression values were normalized to UBQ5 (WT set to 1). Bars show mean ± SD (n = 3 technical replicates, repeated with two biological replicates with similar results). Different lowercase letters denote significant differences (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, P < 0.05). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

4 Discussion

In this study, we identified OsPIN9 as a direct transcriptional target of OUR1/OsbZIP1 and established a module that regulates auxin transport and signaling at the stem base to promote CR development by initiating CRPs. Loss of OUR1/OsbZIP1 function derepresses OsPIN9, increasing auxin flux toward the CR initiation zone. Accordingly, the our1 mutant showed markedly increased CR and tiller numbers under nutrient-sufficient conditions. EMSA and ChIP–qPCR confirmed the direct binding of OUR1/OsbZIP1 to the OsPIN9 promoter, and disrupting the defined OUR1/OsbZIP1 binding site increases OsPIN9 expression, supporting the negative regulation of OsPIN9 by OUR1/OsbZIP1. Mechanistically, we propose that the upregulated OsPIN9 enhances auxin efflux from the peripheral cylinder of vascular bundles toward the innermost ground meristem at the stem base, thereby triggering CRP initiation. Three lines of evidence support this model in our1 mutant background: (i) increased DR5 reporter activity precisely at the CRP initiation site; (ii) upregulation of auxin-responsive Aux/IAA genes together with the CR inducers CRL1, CRL5, and OsWOX11; and (iii) loss or reduction of these responses, together with attenuation of the enhanced CR phenotype, in the pin9 our1 double mutant compared to the our1 single mutant. Taken together, these findings define an OUR1/OsbZIP1–OsPIN9 module that regulates CR formation in rice via an auxin-dependent pathway.

The previous study showed that our1/Osbzip1 mutant shows restricted auxin signaling, which promotes root elongation but suppresses CR formation (Hasegawa et al., 2021). By contrast, our data reveal a stem base specific increase in local auxin signaling that promotes CRP initiation in the our1 mutant under nutrient-sufficient, especially ammonium-rich conditions. We propose that these opposite effects arise from different tissue and nutrient context. Consistent with auxin’s process-specific actions: high auxin level inhibits cell elongation in the root elongation zone (Sun et al., 2014, 2018; Nakamura et al., 2023), yet a local auxin maximum at the stem base triggers CRP initiation (Kitomi et al., 2008; Dabravolski and Isayenkov, 2025). According, under filtered water, globally restricted auxin signaling across the root system in the our1 mutant promotes root elongation but suppresses CR formation. In this context, although OsPIN9 is derepressed, the promotion of auxin signaling by OsPIN9 is insufficient to induce CRP initiation, and CR numbers remain low in the our1 mutant. By contrast, under nutrient-sufficient condition, it has been reported that other PINs such as OsPIN1b are upregulated and transport auxin from younger shoot part to the stem base (Sun et al., 2018). Therefore, under nutrient conditions, sufficient auxin is thought to accumulate at the stem base even in the our1 mutant. The highly upregulated OsPIN9 in the peripheral cylinder of vascular bundles is proposed to transport auxin into innermost ground meristem, establishing a local auxin maximum and thereby promoting CRP initiation in the our1 mutant.

Previous studies have established that PIN-mediated polar auxin transport underpins key steps in CR development (Xu et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2009; Hou et al., 2021) and that CRL1, CRL5, and OsWOX11 function as core auxin-responsive regulators of CR initiation and emergence (Inukai et al., 2005; Kitomi et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2018). Within the rice PIN family, OsPIN9 is highly expressed in the peripheral vascular bundles of the basal internodes and has been implicated in CR development and tiller number, consistent with its role at the stem base (Wang et al., 2009; Miyashita et al., 2010; Hou et al., 2021). However, transcriptional regulation of OsPIN9 remains unclear. Here, we newly identified a transcription factor OUR1/OsbZIP1, that directly represses OsPIN9 expression. Together with previous evidence that OsWOX11 acts upstream of OsPIN9 to promote OsPIN9 expression and CR emergence (Zhou et al., 2017), a dual regulatory pathway was revealed: activation by OsWOX11 and repression by OUR1/OsbZIP1, controlling OsPIN9 expression. Furthermore, because OsWOX11 is auxin-inducible and OsPIN9 controls polar auxin transport at the stem base, we propose that OsPIN9-driven auxin flux promotes OsWOX11 expression, forming a potential modest positive feedback loop between OsPIN9 and OsWOX11 that promotes CR initiation. Nevertheless, under filtered water, OsWOX11 expression is reduced in the our1 mutant, consistent with the inhibited auxin signaling; thus, the proposed OsPIN9–auxin–OsWOX11 positive feedback remains to be tested under conditions that support CR initiation. In addition to OsPIN9, OsPIN8, OsPIN10a, and OsPIN10b are upregulated in the our1 mutant; notably, all three promoters contain ACGT-core bZIP motifs, suggesting potential regulation by OUR1/OsbZIP1. Among them, OsPIN10a has been functionally implicated in CR formation (Wang et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2012). Further study will be required to determine whether these loci constitute a broader OUR1/OsbZIP1–PIN module contributing to CR initiation.

Previous studies demonstrated that OsbZIP1 plays a critical role in regulating nutrient uptake, root system development, and grain yield (Hasegawa et al., 2021; Tanaka et al., 2024; Xiong et al., 2024). Our findings broaden this framework by identifying OsbZIP1 as an upstream integrator of auxin transport and signaling through the repression of OsPIN9, thereby extending its function to CR regulation. From an applied perspective, the OUR1/OsbZIP1–OsPIN9 module provides a novel tractable point for optimizing rice root system architecture (RSA). The our1 mutant has been reported to exhibit enhanced SR elongation and promoted LR formation, which maintains the yield under drought-prone conditions (Hasegawa et al., 2021, 2022). In parallel, OsPIN9 overexpression has been associated with increased tiller number and reduced nitrogen fertilizer requirements (Hou et al., 2021), and OsPIN9 expression is significantly induced by salt and drought treatments (Manna et al., 2022), together suggesting a strategy to enhance nutrient-use efficiency, abiotic stress adaptation, and productivity. These observations raise the testable prediction: our1 mutant lines with activated OsPIN9 activity may deliver yield gains under low nitrogen input and stress-prone conditions. To evaluate breeding utility, further comparative analyses across cultivars should be conducted to determine whether the OUR1/OsbZIP1–OsPIN9 module can be generalized to design RSA that sustain yield under nutrient limitation and abiotic stress.

In conclusion, we identified OUR1/OsbZIP1 as a direct negative regulator of OsPIN9, thereby establishing an OUR1/OsbZIP1–OsPIN9 module involving an auxin-dependent pathway to control CR formation in rice. This study provides a practical framework for manipulating CR development to improve RSA and crop performance.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

YD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Visualization. CW: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation. TK: Data curation, Writing – original draft. YI: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was financially supported by JST SPRING, Grant Number JPMJSP2125, MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 24K01729 and 24KK0121.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kimiyo Inukai and Eiko Murakami (International Center for Research and Education in Agriculture, Nagoya University), and Shinya Mizuno and Ko Ito (Technical Center, Nagoya University) for their valuable technical support; Masafumi Mikami, Seiichi Toki, and Masaki Endo (National Agriculture and Food Research Organization) for providing the CRISPR/Cas9 vectors; Prof. Hiroyuki Tsuji and Dr. Moeko Sato for providing the DR5:NLS-3xVenus vector. The author, YD, would like to take this opportunity to thank the “THERS Make New Standards Program for the Next Generation Researchers”.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1718647/full#supplementary-material

References

Benková, E., Michniewicz, M., Sauer, M., Teichmann, T., Seifertová, D., Jürgens, G., et al. (2003). Local, efflux-dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation. Cell 115, 591–602. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00924-3

Bhatnagar, A., Burman, N., Sharma, E., Tyagi, A., Khurana, P., and Khurana, J. P. (2023). Two splice forms of OsbZIP1, a homolog of AtHY5, function to regulate skotomorphogenesis and photomorphogenesis in rice. Plant Physiol. 193, 426–447. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiad334

Chai, J., Zhu, S., Li, C., Wang, C., Cai, M., Zheng, X., et al. (2021). OsRE1 interacts with OsRIP1 to regulate rice heading date by finely modulating Ehd1 expression. Plant Biotechnol. J. 19, 300–310. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13462

Chapman, E. J. and Estelle, M. (2009). Mechanism of auxin-regulated gene expression in plants. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 265–285. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134148

Cluis, C. P., Mouchel, C. F., and Hardtke, C. S. (2004). The Arabidopsis transcription factor HY5 integrates light and hormone signaling pathways. Plant J. 38, 332–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02052.x

Colmer, T. D. (2003). Aerenchyma and an inducible barrier to radial oxygen loss facilitate root aeration in upland, paddy and deep-water rice (Oryza sativa L.). Ann. Bot. 91, 301–309. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf114

Coudert, Y., Périn, C., Courtois, B., Khong, N. G., and Gantet, P. (2010). Genetic control of root development in rice, the model cereal. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.01.008

Dabravolski, S. A. and Isayenkov, S. V. (2025). Exploring hormonal pathways and gene networks in crown root formation under stress conditions: an update. Plants 14, 630. doi: 10.3390/plants14040630

Dharmasiri, N., Dharmasiri, S., and Estelle, M. (2005). The F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature 435, 441–445. doi: 10.1038/nature03543

Fitzgerald, M. A., McCouch, S. R., and Hall, R. D. (2009). Not just a grain of rice: the quest for quality. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.12.004

Foster, R., Izawa, T., and Chua, N. (1994). Plant bZIP proteins gather at ACGT elements. FASEB J. 8, 192–200. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119490

Friml, J., Vieten, A., Sauer, M., Weijers, D., Schwarz, H., Hamann, T., et al. (2003). Efflux-dependent auxin gradients establish the apical–basal axis of Arabidopsis. Nature 426, 147–153. doi: 10.1038/nature02085

Friml, J., Wiśniewska, J., Benková, E., Mendgen, K., and Palme, K. (2002). Lateral relocation of auxin efflux regulator PIN3 mediates tropism in Arabidopsis. Nature 415, 806–809. doi: 10.1038/415806a

Fukagawa, N. K. and Ziska, L. H. (2019). Rice: importance for global nutrition. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 65, S2–S3. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.65.S2

Gao, S., Fang, J., Xu, F., Wang, W., Sun, X., Chu, J., et al. (2014). CYTOKININ OXIDASE/DEHYDROGENASE4 integrates cytokinin and auxin signaling to control rice crown root formation. Plant Physiol. 165, 1035–1046. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.238584

Geldner, N., Anders, N., Wolters, H., Keicher, J., Kornberger, W., Muller, P., et al. (2003). The arabidopsis GNOM ARF-GEF mediates endosomal recycling, auxin transport, and auxin-dependent plant growth. Cell 112, 219–230. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00003-5

Geng, L., Li, Q., Jiao, L., Xiang, Y., Deng, Q., Zhou, D., et al. (2023). WOX11 and CRL1 act synergistically to promote crown root development by maintaining cytokinin homeostasis in rice. New Phytol. 237, 204–216. doi: 10.1111/nph.18522

Geng, L., Tan, M., Deng, Q., Wang, Y., Zhang, T., Hu, X., et al. (2024). Transcription factors WOX11 and LBD16 function with histone demethylase JMJ706 to control crown root development in rice. Plant Cell 36, 1777–1790. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koad318

Gray, W. M., Kepinski, S., Rouse, D., Leyser, O., and Estelle, M. (2001). Auxin regulates SCFTIR1-dependent degradation of AUX/IAA proteins. Nature 414, 271–276. doi: 10.1038/35104500

Haeussler, M., Schönig, K., Eckert, H., Eschstruth, A., Mianné, J., Renaud, J.-B., et al. (2016). Evaluation of off-target and on-target scoring algorithms and integration into the guide RNA selection tool CRISPOR. Genome Biol. 17, 148. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1012-2

Hasegawa, J., Sakamoto, Y., Nakagami, S., Aida, M., Sawa, S., and Matsunaga, S. (2016). Three-dimensional imaging of plant organs using a simple and rapid transparency technique. Plant Cell Physiol. 57, 462–472. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcw027

Hasegawa, T., Lucob-Agustin, N., Yasufuku, K., Kojima, T., Nishiuchi, S., Ogawa, A., et al. (2021). Mutation of OUR1/OsbZIP1, which encodes a member of the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family, promotes root development in rice through repressing auxin signaling. Plant Sci. 306, 110861. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2021.110861

Hasegawa, T., Wainaina, C. M., Shibata, A., Lucob-Agustin, N., Makihara, D., Kikuta, M., et al. (2022). The outstanding rooting1 mutation gene maintains shoot growth and grain yield through promoting root development in rice under water deficit field environments. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 208, 815–829. doi: 10.1111/jac.12524

Hiei, Y., Ohta, S., Komari, T., and Kumashiro, T. (1994). Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J. 6, 271–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1994.6020271.x

Holz, M., Zarebanadkouki, M., Benard, P., Hoffmann, M., and Dubbert, M. (2024). Root and rhizosphere traits for enhanced water and nutrients uptake efficiency in dynamic environments. Front. Plant Sci. 15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1383373

Hou, M., Luo, F., Wu, D., Zhang, X., Lou, M., Shen, D., et al. (2021). OsPIN9, an auxin efflux carrier, is required for the regulation of rice tiller bud outgrowth by ammonium. New Phytol. 229, 935–949. doi: 10.1111/nph.16901

Inukai, Y., Sakamoto, T., Ueguchi-Tanaka, M., Shibata, Y., Gomi, K., Umemura, I., et al. (2005). Crown rootless1, which is essential for crown root formation in rice, is a target of an AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR in auxin signaling. Plant Cell 17, 1387–1396. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.030981

Itoh, J.-I., Nonomura, K.-I., Ikeda, K., Yamaki, S., Inukai, Y., Yamagishi, H., et al. (2005). Rice plant development: from zygote to spikelet. Plant Cell Physiol. 46, 23–47. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci501

Izawa, T., Foster, R., and Chua, N.-H. (1993). Plant bZIP protein DNA binding specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 230, 1131–1144. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1230

Jain, M., Kaur, N., Garg, R., Thakur, J. K., Tyagi, A. K., and Khurana, J. P. (2006). Structure and expression analysis of early auxin-responsive Aux/IAA gene family in rice (Oryza sativa). Funct. Integr. Genomics 6, 47–59. doi: 10.1007/s10142-005-0005-0

Jakoby, M., Weisshaar, B., Dröge-Laser, W., Vicente-Carbajosa, J., Tiedemann, J., Kroj, T., et al. (2002). bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 106–111. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)02223-3

Kawai, T., Akahoshi, R., Shelley, I. J., Kojima, T., Sato, M., Tsuji, H., et al. (2022a). Auxin distribution in lateral root primordium development affects the size and lateral root diameter of rice. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.834378

Kawai, T., Shibata, K., Akahoshi, R., Nishiuchi, S., Takahashi, H., Nakazono, M., et al. (2022b). WUSCHEL-related homeobox family genes in rice control lateral root primordium size. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2101846119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2101846119

Kitomi, Y., Ito, H., Hobo, T., Aya, K., Kitano, H., and Inukai, Y. (2011). The auxin responsive AP2/ERF transcription factor CROWN ROOTLESS5 is involved in crown root initiation in rice through the induction of OsRR1, a type-A response regulator of cytokinin signaling. Plant J. 67, 472–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04610.x

Kitomi, Y., Ogawa, A., Kitano, H., and Inukai, Y. (2008). CRL4 regulates crown root formation through auxin transport in rice. Plant Root. 2, 19–28. doi: 10.3117/plantroot.2.19

Kojima, T., Hashimoto, Y., Kato, M., Kobayashi, T., and Nakano, H. (2010). High-throughput screening of DNA binding sites for transcription factor AmyR from Aspergillus nidulans using DNA beads display system. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 109, 519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.11.024

Liu, S., Wang, J., Wang, L., Wang, X., Xue, Y., Wu, P., et al. (2009). Adventitious root formation in rice requires OsGNOM1 and is mediated by the OsPINs family. Cell Res. 19, 1110–1119. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.70

Liu, H., Wang, S., Yu, X., Yu, J., He, X., Zhang, S., et al. (2005). ARL1, a LOB-domain protein required for adventitious root formation in rice. Plant J. 43, 47–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02434.x

Lucob-Agustin, N., Kawai, T., Takahashi-Nosaka, M., Kano-Nakata, M., Wainaina, C. M., Hasegawa, T., et al. (2020). WEG1, which encodes a cell wall hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein, is essential for parental root elongation controlling lateral root formation in rice. Physiol. Plant. 169, 214–227. doi: 10.1111/ppl.13063

Lynch, J. P. (2019). Root phenotypes for improved nutrient capture: an underexploited opportunity for global agriculture. New Phytol. 223, 548–564. doi: 10.1111/nph.15738

Mai, C. D., Phung, N. T., To, H. T., Gonin, M., Hoang, G. T., Nguyen, K. L., et al. (2014). Genes controlling root development in rice. Rice 7, 30. doi: 10.1186/s12284-014-0030-5

Manna, M., Rengasamy, B., Ambasht, N. K., and Sinha, A. K. (2022). Characterization and expression profiling of PIN auxin efflux transporters reveal their role in developmental and abiotic stress conditions in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1059559

Mao, C., He, J., Liu, L., Deng, Q., Yao, X., Liu, C., et al. (2020). OsNAC2 integrates auxin and cytokinin pathways to modulate rice root development. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 429–442. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13209

Meng, F., Xiang, D., Zhu, J., Li, Y., and Mao, C. (2019). Molecular mechanisms of root development in rice. Rice 12, 1. doi: 10.1186/s12284-018-0262-x

Mikami, M., Toki, S., and Endo, M. (2015). Comparison of CRISPR/Cas9 expression constructs for efficient targeted mutagenesis in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 88, 561–572. doi: 10.1007/s11103-015-0342-x

Miyashita, Y., Takasugi, T., and Ito, Y. (2010). Identification and expression analysis of PIN genes in rice. Plant Sci. 178, 424–428. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.02.018

Mohidem, N. A., Hashim, N., Shamsudin, R., and Che Man, H. (2022). Rice for food security: revisiting its production, diversity, rice milling process and nutrient content. Agriculture 12, 741. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12060741

Muthayya, S., Sugimoto, J. D., Montgomery, S., and Maberly, G. F. (2014). An overview of global rice production, supply, trade, and consumption. Ann. New York. Acad. Sci. 1324, 7–14. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12540

Nakagawa, T., Suzuki, T., Murata, S., Nakamura, S., Hino, T., Maeo, K., et al. (2007). Improved gateway binary vectors: high-performance vectors for creation of fusion constructs in transgenic analysis of plants. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 2095–2100. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70216

Nakamura, A., Hirota, Y., Shigihara, M., Watanabe, M., Sato, A., Tsuji, H., et al. (2023). Molecular and cellular insights into auxin-regulated primary root growth: a comparative study of Arabidopsis and rice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 87, 1145–1154. doi: 10.1093/bbb/zbad089

Nakamura, S., Nakao, A., Kawamukai, M., Kimura, T., Ishiguro, S., and Nakagawa, T. (2009). Development of gateway binary vectors, R4L1pGWBs, for promoter analysis in higher plants. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73, 2556–2559. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90720

Ozawa, K. (2009). Establishment of a high efficiency Agrobacterium-mediated transformation system of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Sci. 176, 522–527. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.01.013

Paponov, I., Teale, W., Trebar, M., Blilou, I., and Palme, K. (2005). The PIN auxin efflux facilitators: evolutionary and functional perspectives. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.02.009

Rebouillat, J., Dievart, A., Verdeil, J. L., Escoute, J., Giese, G., Breitler, J. C., et al. (2009). Molecular genetics of rice root development. Rice 2, 15–34. doi: 10.1007/s12284-008-9016-5

Sato, Y., Takehisa, H., Kamatsuki, K., Minami, H., Namiki, N., Ikawa, H., et al. (2013). RiceXPro Version 3.0: expanding the informatics resource for rice transcriptome. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D1206–D1213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1125

Shao, Y., Zhou, H.-Z., Wu, Y., Zhang, H., Lin, J., Jiang, X., et al. (2019). OsSPL3, an SBP-domain protein, regulates crown root development in rice. Plant Cell 31, 1257–1275. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00038

Sun, H., Tao, J., Bi, Y., Hou, M., Lou, J., Chen, X., et al. (2018). OsPIN1b is involved in rice seminal root elongation by regulating root apical meristem activity in response to low nitrogen and phosphate. Sci. Rep. 8, 13014. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29784-x

Sun, H., Tao, J., Liu, S., Huang, S., Chen, S., Xie, X., et al. (2014). Strigolactones are involved in phosphate- and nitrate-deficiency-induced root development and auxin transport in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 6735–6746. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru029

Tanaka, N., Yoshida, S., Islam, M., Yamazaki, K., Fujiwara, T., and Ohmori, Y. (2024). OsbZIP1 regulates phosphorus uptake and nitrogen utilization, contributing to improved yield. Plant J. 118, 159–170 doi: 10.1111/tpj.16598

Thorup-Kristensen, K. and Kirkegaard, J. (2016). Root system-based limits to agricultural productivity and efficiency: the farming systems context. Ann. Bot. 118, 573–592. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcw122

Tiwari, S. B., Hagen, G., and Guilfoyle, T. J. (2004). Aux/IAA proteins contain a potent transcriptional repression domain. Plant Cell 16, 533–543. doi: 10.1105/tpc.017384

Tracy, S. R., Nagel, K. A., Postma, J. A., Fassbender, H., Wasson, A., and Watt, M. (2020). Crop improvement from phenotyping roots: highlights reveal expanding opportunities. Trends Plant Sci. 25, 105–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.10.015

Tracy, S., Schneider, H., and Kant, J. (2023). Editorial: Increasing crop yield: the interaction of crop plant roots with their environment. Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1249270

Vieten, A., Vanneste, S., Wiśniewska, J., Benková, E., Benjamins, R., Beeckman, T., et al. (2005). Functional redundancy of PIN proteins is accompanied by auxin-dependent cross-regulation of PIN expression. Development 132, 4521–4531. doi: 10.1242/dev.02027

Wang, J.-R., Hu, H., Wang, G.-H., Li, J., Chen, J.-Y., and Wu, P. (2009). Expression of PIN genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.): tissue specificity and regulation by hormones. Mol. Plant 2, 823–831. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp023

Wang, H., Tang, X., Yang, X., Fan, Y., Xu, Y., Li, P., et al. (2021). Exploiting natural variation in crown root traits via genome-wide association studies in maize. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 346. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-03127-x

Xinli, D., Yang, Z., Yaqi, Z., Fuxi, R., Jiahong, D., Zheyuan, H., et al. (2024). OsbZIP01 affects plant growth and development by regulating osSD1 in rice. Rice Sci. 31, 77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.rsci.2023.11.007

Xiong, D., Wang, J., Wang, R., Wang, Y., Li, Y., Sun, G., et al. (2024). A point mutation in VIG1 boosts development and chilling tolerance in rice. Nat. Commun. 15, 8212. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-52510-3

Xu, H., Yang, X., Zhang, Y., Wang, H., Wu, S., Zhang, Z., et al. (2022). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutation in auxin efflux carrier OsPIN9 confers chilling tolerance by modulating reactive oxygen species homeostasis in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.967031

Xu, M., Zhu, L., Shou, H., and Wu, P. (2005). A PIN1 family gene, osPIN1, involved in auxin-dependent adventitious root emergence and tillering in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 46, 1674–1681. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci183

Yamaguchi, N., Winter, C. M., Wu, M.-F., Kwon, C. S., William, D. A., and Wagner, D. (2014). PROTOCOL: chromatin immunoprecipitation from arabidopsis tissues. Arabidopsis. Book. 12, e0170. doi: 10.1199/tab.0170

Yamauchi, A., Kono, Y., and Tatsumi, J. (1987). Quantitative analysis on root system structures of upland rice and maize. Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 56, 608–617. doi: 10.1626/jcs.56.608

Yara, A., Otani, M., Kusumi, K., Matsuda, O., Shimada, T., and Iba, K. (2001). Production of transgenic japonica rice (Oryza sativa) cultivar, taichung 65, by the agrobacterium-mediated method. Plant Biotechnol. 18, 305–310. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.18.305

Zhang, T., Li, R., Xing, J., Yan, L., Wang, R., and Zhao, Y. (2018). The YUCCA-auxin-WOX11 module controls crown root development in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00523

Zhang, Q., Li, J., Zhang, W., Yan, S., Wang, R., Zhao, J., et al. (2012). The putative auxin efflux carrier OsPIN3t is involved in the drought stress response and drought tolerance. Plant J. 72, 805–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05121.x

Zhao, Y., Cheng, S., Song, Y., Huang, Y., Zhou, S., Liu, X., et al. (2015). The interaction between rice ERF3 and WOX11 promotes crown root development by regulating gene expression involved in cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell 27, 2469–2483. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00227

Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Dai, M., Huang, L., and Zhou, D.-X. (2009). The WUSCHEL-related homeobox gene WOX11 is required to activate shoot-borne crown root development in rice. Plant Cell 21, 736–748. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061655

Keywords: rice, OsbZIP1 transcription factor, OsPIN9, auxin, crown root formation

Citation: Dong Y, Wainaina CM, Kojima T and Inukai Y (2025) OUR1/OsbZIP1-OsPIN9 regulatory module controls auxin-dependent crown root formation in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1718647. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1718647

Received: 04 October 2025; Accepted: 19 November 2025; Revised: 13 November 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited by:

Jian You Wang, Academia Sinica, TaiwanCopyright © 2025 Dong, Wainaina, Kojima and Inukai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yoshiaki Inukai, aW51a2FpeUBhZ3IubmFnb3lhLXUuYWMuanA=

Yihao Dong

Yihao Dong Cornelius Mbathi Wainaina2

Cornelius Mbathi Wainaina2 Yoshiaki Inukai

Yoshiaki Inukai