- 1Aquatic and Crop Resource Development, National Research Council of Canada (NRC), Saskatoon, SK, Canada

- 2Anandi Botanicals Inc., Lethbridge, AB, Canada

The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) holds great promise for revolutionizing the fields of plant tissue culture and genome editing. Plant tissue culture is recognized as a powerful tool for rapid multiplication and crop improvement. However, the complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors generate large volumes of data, posing challenges for traditional statistical analysis methods. To address this, researchers are now employing machine learning (ML)-based and artificial neural networks (ANN) approaches to predict and optimize in vitro culture protocols thereby improving precision, sustainability, and efficiency. Integrating AI technologies such as machine learning (ML), artificial neural networks (ANN), and deep learning (DL) can significantly advance the development of data-driven models for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Today, AI-driven methods are routinely applied to enhance precision in predicting on- and off-target sequence locations and editing outcomes. Additionally, predicting protein structures can provide a directed evolution framework that facilitates the creation of improved gene editing tools. However, the application of AI-based CRISPR modeling in plants is not yet fully explored. In this context, we aim to examine representative ML/DL/ANN models of CRISPR/Cas based editing employed in various organisms. This review significantly compiles a diverse set of studies and provides a clear overview of how AI is transforming the fields of plant tissue culture and genome editing. It emphasizes AI’s potential to increase the efficiency and precision of biotechnological practices, making them more accessible and cost-effective. While outlining current findings, the paper sets the stage for future research, encouraging further exploration into the integration of AI with plant biotechnology.

1 Introduction

In recent years, plant biotechnology has made significant strides, notably by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) with plant tissue culture and genome editing, that represents a transformative advancement in plant biotechnology, offering powerful tools to accelerate crop improvement. Plant tissue culture and CRISPR/Cas genome editing have each revolutionized plant breeding and genetic engineering (Ibrahim et al., 2023). Incorporating AI techniques further enhances these technologies by enabling faster, more accurate, and cost-effective optimization of culture protocols and precise genetic modifications. AI models excel at deciphering complex, non-linear patterns in large biological datasets, enhancing predictions of growth responses, culture conditions, and editing outcomes (Kaushik et al., 2025). The continued advancement and adoption of AI methodologies are essential to overcoming existing technical and biological limitations. Harnessing the full potential of AI, in conjunction with plant tissue culture and genome editing, will drive the development of sustainable, precision agriculture solutions, supporting global food security, promoting environmental sustainability, and ushering in a new era of innovation in plant sciences.

Plant tissue culture is the sterile cultivation of plant explants on defined media under controlled conditions, leveraging totipotency, the ability of a single cell to regenerate into a whole plant (Phillips and Garda, 2019). It is fundamental to micropropagation, crop improvement, metabolite production, and conservation. To achieve efficient in vitro regeneration, factors such as explant type, nutrient composition and growth regulators must be carefully optimized (Loyola-Vargas and Ochoa-Alejo, 2018). Traditional statistical methods are limited in handling the complexity and non-linearity of in vitro systems, making optimization time-consuming and labor-intensive (Niazian and Niedbała, 2020). Artificial intelligence, especially machine learning and artificial neural networks, enables reliable modeling of complex biological interactions using experimental data. It facilitates accurate prediction and optimization of plant tissue culture stages, while reducing time, cost, and experimental load (Hesami et al., 2020a). The CRISPR/Cas system has emerged as a leading genome engineering platform due to its programmability and targeting flexibility (Liu et al., 2022a; Liu et al., 2022b). Its broad applicability has enabled its use across a wide range of applications, from gene disruption and modification to gene regulation and RNA editing. Despite challenges like off-target effects and variable efficiency, the focus has shifted from feasibility to optimization (Ran et al., 2013, 2015). Machine learning (ML)/Deep learning (DL) offers powerful methods for modeling complex biological systems. By learning patterns from data, AI enables accurate prediction of CRISPR editing outcomes, surpassing the limits of traditional experimentation (Chuai et al., 2017). The integration of deep learning into genomics and genetic engineering presents new opportunities for precision and innovation in gene editing (Eraslan et al., 2019).

While previous reviews have acknowledged the promise of AI)in plant biotechnology, most focus narrowly either on ML applications in plant tissue culture or on CRISPR/Cas-based genome editing in non-plant systems. For instance, certain studies (Hesami and Jones, 2021; Ibrahim et al., 2023; Kaushik et al., 2025) offer valuable overviews of AI in tissue culture optimization but do not address the convergence of AI with gene editing platforms like CRISPR/Cas9. This review is uniquely positioned at the intersection of two critical domains and emphasizes the integrative role of AI across plant tissue culture and genome editing. In addition to summarizing current models and algorithms, this review outlines challenges in data availability, model interpretability, and experimental validation, and proposes concrete future research directions to bridge these gaps. This positions the review as both a resource and a roadmap for researchers aiming to operationalize AI in plant biotechnology.

2 Machine learning-based approaches in plant tissue culture

Plant tissue culture (micropropagation or in vitro cell and tissue culture), is a technique used to grow plants in a nutrient-rich medium under controlled, sterile conditions. It begins with culturing various explants such as leaves, stems, or roots, which due to their totipotency capacity, can regenerate into whole plants and produce multiple plantlets (Loberant and Altman, 2010). This technique has diverse applications, including mass propagation of elite plants, genetic modification, germplasm conservation, and production of disease-free plants (Brown and Thorpe, 1995). In vitro cultures are influenced by several factors, including nutrient media composition, plant genotype, explant type and age, plant growth regulators (PGRs), and phytohormone concentrations (Sudheer et al., 2022). Traditional regression methods and analysis of variance (ANOVA) have been employed for analyzing the data. However, the complexity and non-linearity of biological systems often limit the effectiveness of these techniques (Compton, 2024). In contrast, AI and computer-assisted tools can process continuous, binomial, discrete, and incomplete data, even those generated through unstructured, trial-and-error experiments. This ultimately reduces the need for extensive laboratory experimentation, saving time and resources in optimizing conditions for in vitro culture (Sarker, 2022).

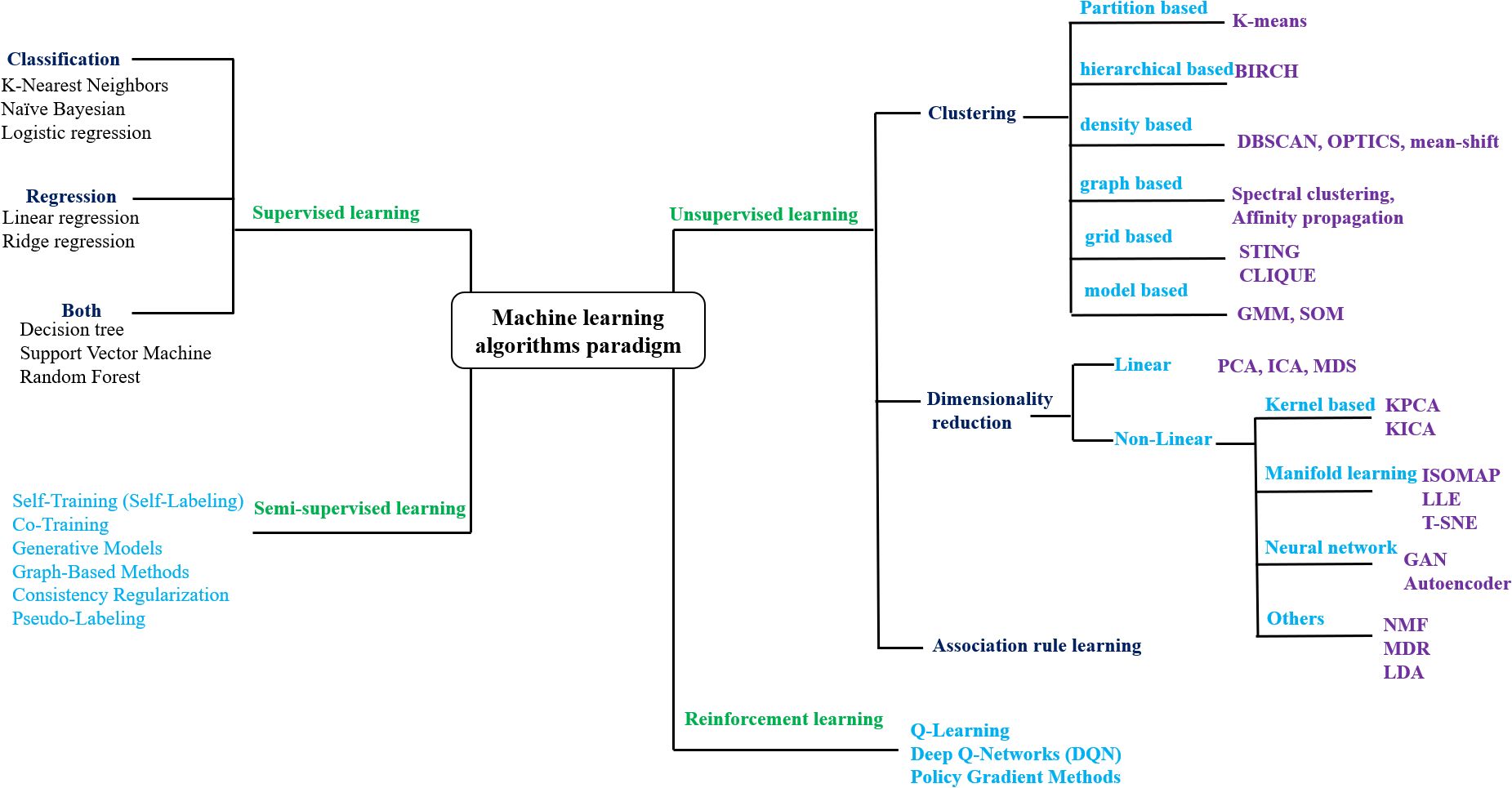

ML has emerged as a powerful tool for addressing this challenge, enabling computers to learn from data and make accurate predictions and classifications (Ray, 2019). ML techniques include supervised learning, where models are trained on labeled datasets for precise prediction and classification (Alloghani et al., 2020); unsupervised learning, which identifies patterns in unlabeled data for clustering and analysis (Alloghani et al., 2020); reinforcement learning, which improves performance through trial-and-error interactions with the environment (Szepesvári, 2010); and semi-supervised learning, that integrates limited labeled data with abundant unlabeled data to enhance model accuracy, particularly when labeling is costly or time-consuming (Zhu and Goldberg, 2009) (Figure 1). In plant tissue culture research, recent advances have leveraged ML to interpret complex, nonlinear data. Hybrid approaches combining ML with optimization algorithms have been used to analyze the relationships between variables. As a result, data-driven approaches are increasingly used to model and optimize tissue culture conditions, including media composition and other critical parameters (Sarker, 2022). A comprehensive literature review was conducted to collect the data specific to plant tissue culture. Using online databases, google scholar, pubmed and scopus were searched for relevant studies with keywords such as “MACHINE LEARNING IN PLANT TISSUE CULTURE”, “ANN IN PLANT TISSUE CULTURE”. Selected peer-reviewed publications with machine learning application in plant tissue culture techniques were screened and considered for writing this review article (Table 1).

Figure 1. Taxonomy of machine learning algorithm paradigms. BIRCH, Balanced Iterative Reducing and Clustering Using Hierarchies; DBSCAN, Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise; OPTICS, Ordering Points To Identify the Clustering Structure; STING, STatistical INformation Grid; CLIQUE), CLustering In QUEst; GMM, Gaussian Mixture Models; SOM, Self-Organizing Map; PCA, Principal Component Analysis; ICA, Independent Component Analysis; MDS, MultiDimensional Scaling; KPCA, Kernel PCA; KICA, Kernel ICA; ISOMAP, ISOmetric feature MAPping; LLE, Locally Linear Embedding; t-SNE, t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding; NMF, N on-negative Matrix Factorization; MDR, Multifactor Dimensionality Reduction; LDA, Latent Dirichlet Allocation; GAN, Generative Adversarial Network.

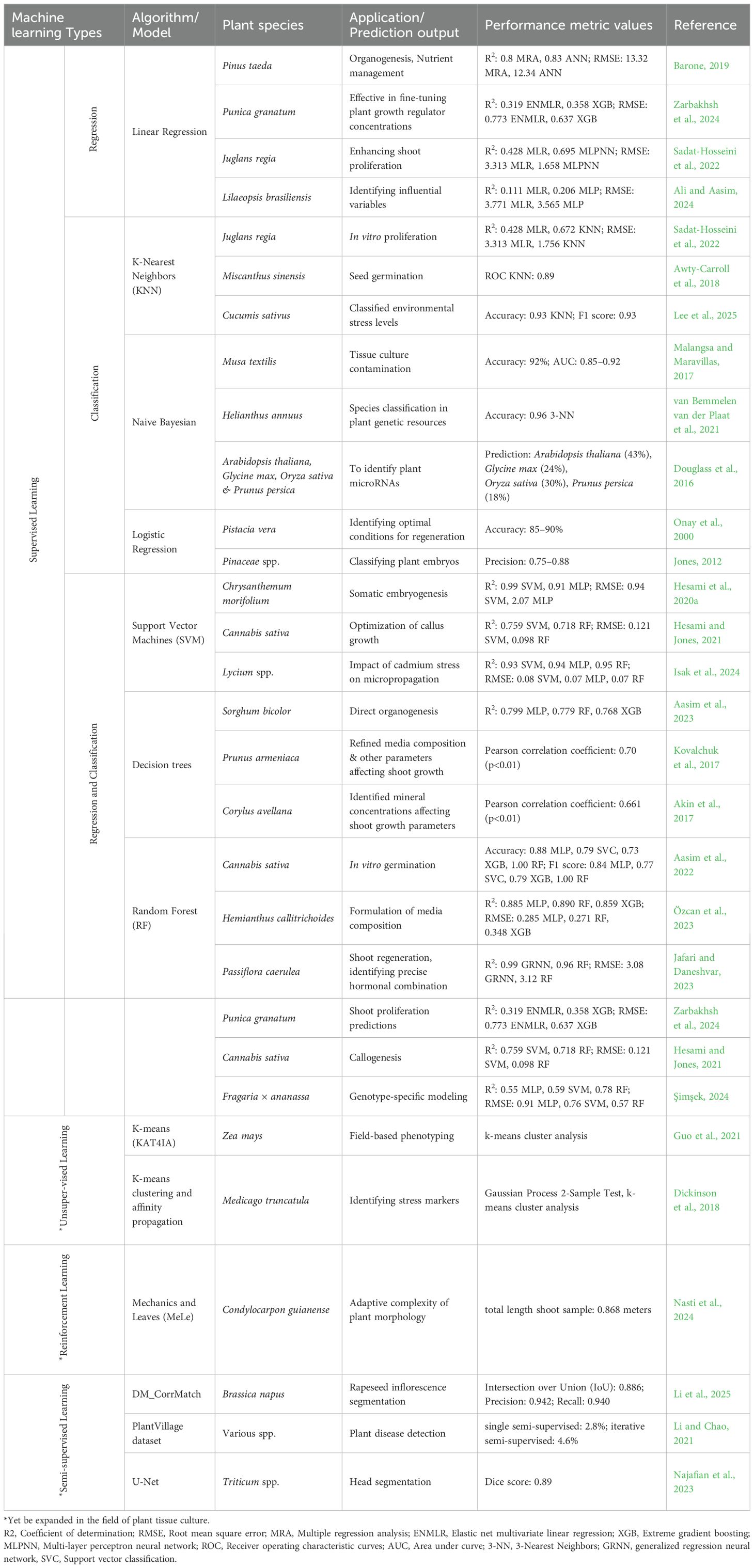

Table 1. Applications of machine learning-based approaches/models used in plant tissue culture and other prediction studies.

2.1 Supervised learning

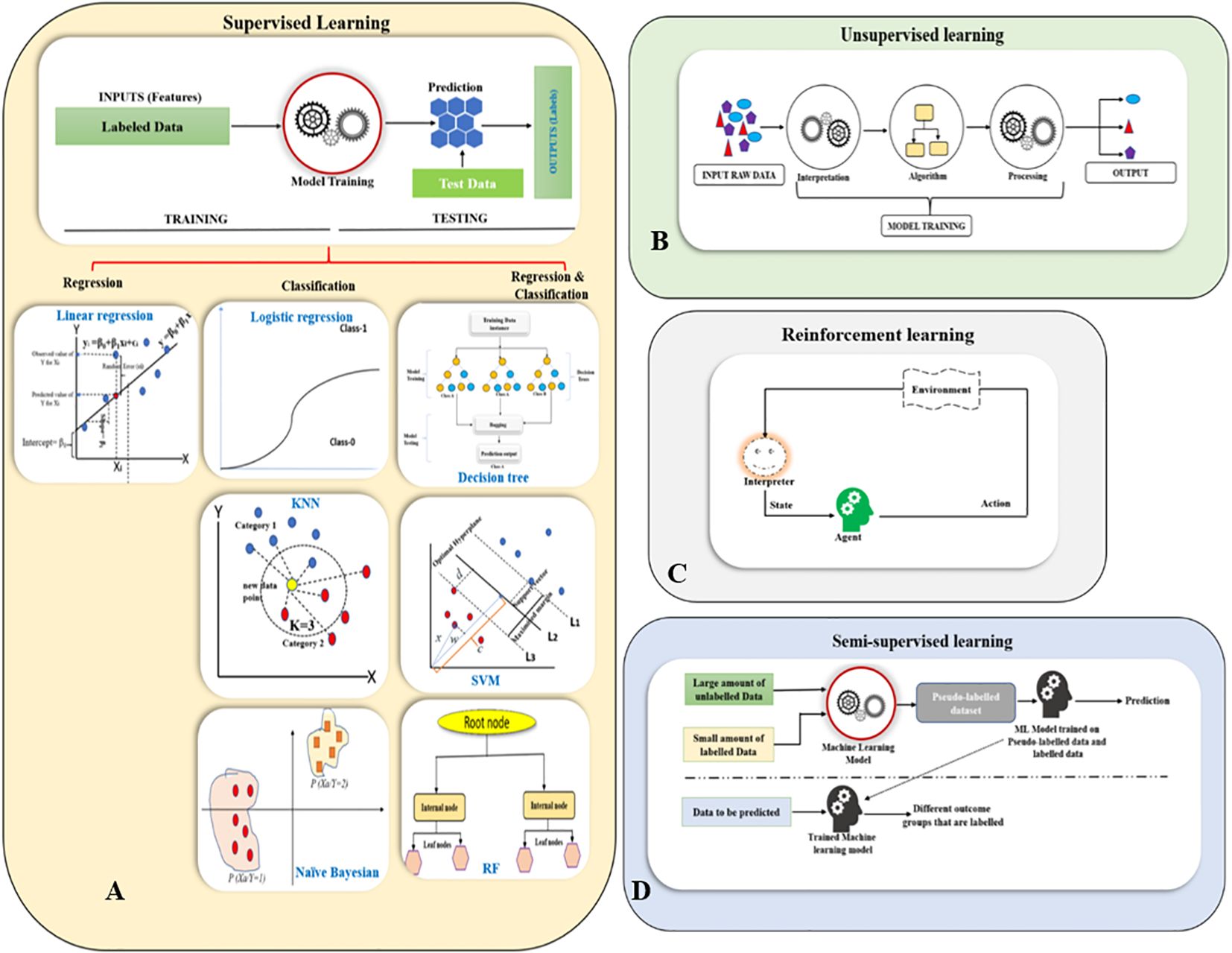

Supervised learning is a subset of machine learning that employs labeled datasets to train algorithm models for analysis and prediction in plant tissue culture research. The success of tissue culture is influenced by variety of factors, including sterilization techniques, plant genotype, growth conditions and media composition. Supervised learning algorithms help to model and predict these outcomes. The process begins with model training by using a dataset that includes input data (features) and corresponding output data (labels or target variables). Once the training is complete, the model is evaluated on a test dataset to assess its accuracy and performance. During the learning process, the algorithm analyzes the relationship between the input features and the output labels (Hastie et al., 2009a). The model’s performance is then fine-tuned by adjusting parameters and cross-validation to balance bias and variance, this sequentially helps to ensure that the model generalizes effectively to new, unseen data. Based on the nature of the output variables, supervised learning can be broadly categorized into (i) Regression, that deals with continuous, numerical outputs without predefined labels, for example, predicting growth rate, biomass accumulation, or shoot multiplication based on factors like temperature, light, or media compositions. (ii) Classification on the other hand, involves categorical outputs with defined labels, such as classifying tissue culture outcomes into categories like successful regeneration, no regeneration, or diseased (Hastie et al., 2009a) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Overview of machine learning paradigms. (A) Supervised Learning (Linear Regression, Logistic Regression, Decision Trees, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Naïve Bayes, and Random Forests (RF); (B) Unsupervised Learning; (C) Reinforcement Learning; (D) Semi-supervised learning.

2.1.1 Linear regression

This is used to predict continuous variables based on one or more independent variables. It computes the linear relationship between the dependent variable and one or more independent features by fitting a linear equation to the observed data. The primary objective of linear regression is to find the best-fit line, which minimizes the error between predicted and actual values. Here the dependent variables (Y), the output you want to predict (e.g., plant growth rate, biomass) and independent variables (X), the factors affecting the output (e.g., temperature, humidity, light intensity) (Equation 1).

Where:

β0 is the intercept (value of y when x=0).

β1 is the coefficient (effect of x on y).

ϵi is the error term (difference between predicted and actual values).

ϵi = y(predicted) – yi

where y(predicted) = β0+β1xi

The equation of this best-fit line represents the relationship between the dependent and independent variables, with the slope indicating how much the dependent variable changes for a unit change in the independent variable(s). Linear regression can be classified further into (i) simple linear regression, that models the relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable by fitting a straight line. The line is defined by an intercept (β0) and a slope (β1), where the slope indicates the change in the dependent variable for each unit increase in the independent variable, and the intercept represents the expected value of the dependent variable when the independent variable is zero. The model aims to minimize the difference between actual and predicted values using a cost function, typically mean squared error (MSE) (Equation 2).

Model performance is also evaluated using metrics like the R-squared (which shows the proportion of explained variance), residual standard error (RSE) and root mean squared error (RMSE). Valid regression requires assumptions such as linearity, independence, normality, and constant variance of residuals. (ii) multiple linear regression, extends this concept to include multiple independent variables (Equation 3):

It follows the same assumptions as simple linear regression, with added concerns like multicollinearity, overfitting, and the need for feature selection. The bias-variance tradeoff is crucial where underfitting occurs when the model is too simple, while overfitting happens when the model captures noise instead of the true pattern, especially in high-dimensional or collinear datasets. Techniques like cross-validation, regularization, and careful feature engineering help strike the right balance. In summary, linear regression is a foundational tool in data science and machine learning, valued for its interpretability and effectiveness. It not only helps make accurate predictions but also lays the groundwork for more complex modeling approaches (Hastie et al., 2009b).

Research application

The reviewed studies collectively highlight the exponential use of integrated regression-based machine learning techniques in optimizing plant tissue culture protocols. In pomegranate, a combination of Bayesian-tuned ensemble stacking regression and non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm-II (NSGA-II) proved effective in fine-tuning plant growth regulators (PGR) concentrations, enhancing shoot proliferation while minimizing somaclonal variation (Zarbakhsh et al., 2024). Similarly, in Pinus taeda, multiple regression and neural networks revealed nitrogen concentration as a key factor in organogenesis, emphasizing the need for precise nutrient management (Barone, 2019). The comparative modeling in persian walnut (Juglans regia) revealed that although linear regression offers baseline predictions, advanced models like genetic programming (GEP) and multilayer perceptron neural network (MLPNN) deliver superior accuracy in forecasting in vitro proliferation. The optimization of macronutrient compositions for pear rootstocks leveraged both stepwise regression and AI methods to pinpoint critical factors influencing explant growth, showcasing the synergy between statistical and algorithmic tools (Sadat-Hosseini et al., 2022). Lastly, the application of response surface methodology and regression analysis in brazilian micro sword (Lilaeopsis brasiliensis) regeneration highlighted the practical utility of these models in identifying influential variables. Overall, these studies validate the robustness of regression and hybrid modeling approaches in refining tissue culture conditions across diverse plant species (Ali and Aasim, 2024).

2.1.2 K-nearest neighbors

K-Nearest neighbors (KNN) machine learning algorithm was generally used for classification but can also be applied to regression tasks. It works by finding the “K” closest data points (neighbors) to a given input and makes predictions based on the majority class for classification or the average value for regression (Mucherino et al., 2009). Since KNN makes no assumptions about the underlying data distribution, it is considered as a non-parametric and instance-based learning method. K-nearest neighbors is also called a lazy learner algorithm because it does not learn from the training set immediately; instead, it stores the dataset and performs computations on it only at the time of classification. Cross-validation is a reliable method for choosing the optimal “K” in KNN by dividing the dataset into k parts, training on some, and testing on others, then selecting the k with the highest average accuracy. The k-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm functions with selecting an optimal value for K, which denotes the number of neighbors to consider when making predictions. Next, the algorithm calculates the distance between the target data point and all points in the training set, commonly using Euclidean distance as the measure of similarity, which is a straight-line distance between two points in a plane or space. It then identifies the “K” data points with the smallest distances to the target, designating these as the nearest neighbors (Equation 4) (James et al., 2021).

Research application

Optimizing plant tissue culture media is a complex process influenced by multiple factors including genotype, mineral nutrients, plant growth regulators (PGRs), and vitamins, often resulting in inefficiencies and physiological disorders like browning of callus, shoot tip necrosis and vitrification. In this context, predictive modeling using ML offers a promising solution. In walnut (Juglans regia L.) proliferation, three ML models, multi-layer perceptron neural network (MLPNN), KNN, and gene expression programming (GEP) were evaluated against multiple linear regression (MLR) for their predictive accuracy. All ML models outperformed MLR, with GEP showing the highest R² (0.802 in Chandler and 0.428 in Rayen varieties) and subsequently optimized using particle swarm optimization (PSO). This highlights GEP-PSO as a powerful hybrid tool, while MLPNN and KNN also demonstrated strong estimation abilities (Sadat-Hosseini et al., 2022). Similarly, in miscanthus seed germination, KNN improved phenotype scoring accuracy when compared to human assessments, especially under challenging conditions such as low germination rates and presence of mold. The model achieved a ROC-AUC of 0.69–0.7, improving to 0.89 on optimized image sets, confirming its utility for consistent, automated germination analysis (Awty-Carroll et al., 2018). In cucumber seedlings, ML models combined with image-based feature extraction (color, texture, morphology) effectively classified environmental stress levels. Among the tested models, KNN achieved the highest accuracy (94%), emphasizing its effectiveness in early stress detection and its potential application in precision agriculture for real-time crop monitoring (Lee et al., 2025).

2.1.3 Naive Bayesian

Naive Bayesian is a classification algorithm that uses probability to predict which category a data point belongs to, assuming that all features are unrelated. The naive Bayesian classifier is based on bayes theorem, which describes the probability of an event, based on prior knowledge of conditions that might be related to the event (Webb, 2011) (Equation 5).

The general formula for Bayes’ theorem is:

Where:

P(y/x) is the posterior probability of class y given the features X.

P(x/y) is the likelihood, i.e., the probability of observing the features X given class y.

P(y)is the prior probability of class y.

P(x) is the evidence or the total probability of observing the features X under all classes.

The term “naive” comes from the assumption that all features are independent of each other, given the class label. This assumption simplifies the computation of the likelihood P(x/y), as we can decompose it into the product of individual feature probabilities. Naïve Bayesian classifiers can be broadly categorized based on the type of data they handle. (i) The gaussian naive Bayesian is used when the features are continuous and assumes that these features follow a gaussian (normal) distribution. In this case, the probability P(y∣ X) is estimated using the probability density function (PDF) of the normal distribution. (ii) The multinomial naïve Bayesian, is commonly used for text classification where the features are discrete counts, such as word frequencies in documents. It models the probability of each feature’s occurrence given a particular class using a multinomial distribution. (iii) Lastly, bernoulli naïve Bayesian is employed when the features are binary, representing the presence or absence of a feature (e.g., 0 or 1). It assumes that each feature follows a bernoulli distribution, where the outcomes are binary. Preprocessing steps like color normalization and data augmentation enhance naïve bayes performance by reducing variability and improving generalizability in image-based tissue culture analysis.

Research application

The performances of naïve bayes and KNN classifiers were compared for grading contamination in abaca tissue culture specimens. The methodology involved capturing images with a masking technique, extracting features from mean RGB values and binary images. Specimens were classified as healthy or contaminated, and classifier performance was evaluated using accuracy, precision, and recall. Naïve Bayes outperformed KNN, achieving 76% accuracy, compared to 68% for KNN at K = 3 and 58% at K = 7 (Malangsa and Maravillas, 2017). Different machine learning classifiers like random forest (RF), neighbor-joining (NJ), KNN, and naïve bayes (NB) were evaluated for species classification in plant genetic resources collections in sunflower. The authors found the KNN classifier to be the most reliable, especially for datasets with variability and uncertainty. The study also highlighted the importance of marker selection for improving classifier accuracy and introduced a method to enhance suboptimal datasets, particularly valuable for genebanks with limited high-quality references (van Bemmelen van der Plaat et al., 2021). Douglass et al. (2016) developed a naïve bayes classifier to identify plant microRNAs (miRNAs), which are key regulatory molecules in eukaryotes. Traditional methods, relying on stem-loop structures, often miss low-count miRNAs. Their probabilistic approach uses sequence length, observation counts, miRNA sequence presence, and other features, and was tested on small RNA data from soybean, peach, Arabidopsis, and rice.

2.1.4 Logistic regression

Logistic regression is primarily used for classification tasks (Sperandei, 2014). Unlike linear regression, which predicts continuous values, logistic regression estimates the probability that an input belongs to a specific class. It is mainly employed for binary classification problems, where the output consists of two possible outcomes, such as Yes/No; True/False; or 0/1. The algorithm utilizes a sigmoid function to convert inputs into a probability between 0 and 1. In contrast, multinomial logistic regression is applied when the dependent variable has three or more unordered categories. It extends the binary logistic regression approach to accommodate multiple classes. Lastly, ordinal logistic regression is used when the dependent variable consists of three or more categories with a natural order or ranking, like ratings of “low,” “medium,” and “high.” This model accounts for the inherent order in the categories when making predictions. The logistic regression model is represented by the following equation (Equation 6):

Where:

p(y=1/X) is the probability that the instance belongs to class 1 given the feature vector X.

wTX is the linear combination of the features (i.e., weights and features).

b is the bias term (also called the intercept).

Σ(sigma) is the sigmoid function that maps the linear combination to a probability.

To minimize the loss function, gradient descent is commonly used, iteratively adjusting the model parameters (weights and bias) to reduce the error. In addition to the primary cost function, regularization techniques like L1 (lasso) and L2 (ridge) regularization are often applied to prevent overfitting, especially in cases with high-dimensional data.

Research application

Linear logistic models were used to assess the significance of the treatments and identify optimal conditions for both processes, highlighting BAP’s superior role in regeneration. This study has explored the effects of 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP), abscisic acid (ABA), and sucrose on the germination and plantlet regeneration of pistachio somatic embryos. Germination rates increased with longer culture durations, with BAP and ABA concentrations influencing outcomes, while sucrose had little effect. Similarly, plantlet regeneration improved over time but was inhibited at higher BAP or ABA levels, with ABA reducing the likelihood of regeneration, particularly during extended maturation periods (Onay et al., 2000). A method for classifying plant embryos (Pseudotsuga and Pinus) based on quality using a penalized logistic regression (PLR) model is disclosed. First, image or spectral data are collected from plant embryos with known quality. Next, each data set is assigned a class label corresponding to the embryo’s quality. Then, metrics are calculated from these image or spectral data sets (Jones, 2012).

2.1.5 Support vector machines

A support vector machine is a powerful ML-algorithm used for both classification and regression tasks. It works by finding the optimal line (or hyperplane) that separates data into distinct groups, while maximizing the distance between the closest data points (support vectors) of each group (Vapnik, 2000). A larger margin typically results in better generalization, allowing the model to perform well on new, unseen data. The optimal hyperplane, also known as the “hard margin,” is the one that maximizes this distance, ensuring a clear separation between the classes. A soft margin, on the other hand, allows for some misclassifications or violations of the margin, which helps improve generalization. This optimizes the following equation to balance margin maximization and penalty minimization (Equation 7).

The penalty for violations is typically the hinge loss, which behaves as follows, if a data point is correctly classified and lies within the margin, there is no penalty (loss = 0) and if a data point is misclassified or violates the margin, the hinge loss increases in proportion to the distance of the violation.

During the training phase, the algorithm is fed with labeled data points from both classes. This is for to determine the optimal hyperplane that maximizes the margin between the two classes, ensuring that no data points fall between the hyperplane and the support vectors. Once the model is trained, it enters the testing phase, where it is presented with new, unseen data points. The model then assesses the position of these points relative to the hyperplane and classifies them based on which side of the hyperplane they are located. A kernel is a function that allows support vector machines to handle non-linear data by implicitly mapping inputs to a higher-dimensional space. Common types include the linear kernel, suitable for linearly separable data; the polynomial kernel, which captures more complex relationships using polynomial functions; and the RBF (Radial basis function) kernel, which measures similarity based on the distance between data points.

Research application

Recent studies have demonstrated the effective application of SVM in plant tissue culture, particularly for modeling and optimizing processes such as somatic embryogenesis and callus development. Support vector regression (SVR) was employed to model somatic embryogenesis in chrysanthemum. The SVR model outperformed multilayer perceptron (MLP) models, achieving an R² value greater than 0.92. Furthermore, integrating SVR with the NSGA-II led to optimization of the culture medium, resulting in a 99.09% embryogenesis rate and an average of 56.24 somatic embryos per explant (Hesami et al., 2020a). SVM in combination with random forest (RF) and genetic algorithm (GA) to model and optimize callus growth in Cannabis sativa. This hybrid approach improved prediction accuracy and provided valuable insights into the influence of various factors on callus development (Hesami and Jones, 2021). More recently, a study by Isak et al. (2024) utilized multiple machine learning algorithms, including SVM, to evaluate the impact of cadmium stress on goji berry micropropagation. The SVM model effectively predicted plant growth parameters under different stress conditions, contributing to the development of strategies for mitigating abiotic stress in plant tissue culture.

2.1.6 Decision tree

A decision tree is used for both classification and regression. It models data using a tree-like structure where each internal node represents a decision based on a feature, branches represent outcomes of those decisions, and leaf nodes provide the final prediction (Thomas et al., 2020). The process starts from a root node that represents the entire dataset, and splits it into subsets based on selected features using specific splitting criteria: (i) Entropy (Information theory) measures the impurity or uncertainty in a dataset (Equation 8);

For a dataset D with k classes

Where:

pi is the proportion of samples in class i in dataset D.

Entropy is 0 when all samples belong to one class (pure), and maximum when classes are equally distributed.

(ii) Information Gain (IG) that is used in ID3 algorithm, measures the reduction in entropy after a dataset is split on an attribute A (Equation 9);

Where:

D = dataset before split. = subset of D where attribute A has value . = weight of the subset.

(iii) Gini impurity in the classification and regression trees (CART) algorithm, is another alternative to entropy to measure impurity of a dataset. Like entropy, Gini is 0 for pure datasets and it’s computationally simpler than entropy. These criteria assess how well a feature separates the data. Once the optimal feature is chosen, the dataset is partitioned based on that feature, and the process is repeated recursively on each subset until a stopping condition is met, such as reaching a maximum tree depth, or having a minimum number of samples per node. Since decision trees can overfit the training data, pruning techniques are employed to simplify the model. Common algorithms include iterative dichotomiser 3 (ID3) (using information gain), C4.5 (using gain ratio), CART (using gini impurity or MSE), and chi-squared automatic interaction detector (CHAID) (using Chi-square tests).

Research application

Aasim et al. (2023) successfully established an efficient in vitro regeneration protocol for Sorghum bicolor using direct organogenesis from mature zygotic embryo explants. The use of MS-medium supplemented with varying concentrations of BAP alone or in combination with IBA or NAA significantly influenced shoot count and shoot length, with optimal results observed for 2 mg/L BAP + 0.25 mg/L NAA and 2.0 mg/L BAP, respectively. Statistical analyses using factorial regression, pareto charts, and surface modeling confirmed the substantial effects of cytokinin–auxin interactions. Moreover, the integration of artificial intelligence-based models, including multilayer perceptron (MLP), random forest (RF), and XGBoost, demonstrated the superior predictive accuracy of MLP, highlighting the potential of AI in optimizing tissue culture protocols. In parallel, studies on wild apricot (Prunus armeniaca) (Kovalchuk et al., 2017) and hazelnut (Corylus avellana) employed decision tree algorithms such as CART, CHAID, and exhaustive CHAID to refine media composition and identify key mineral concentrations affecting shoot growth parameters. Particularly, CART proved effective in modeling complex nonlinear relationships and establishing specific cutoff points for components such as KH2PO4, MgSO4, and CuSO4. These findings underscore the relevance of decision tree-based modeling in deciphering multifactorial effects in plant tissue culture, offering a robust framework for media optimization across diverse species (Akin et al., 2017, 2018). The synergy between traditional statistical methods, AI models, and decision tree algorithms enhanced the ability to develop genotype-independent, efficient micropropagation systems, vital for crop improvement and biotechnological applications.

2.1.7 Random forest

Random forest algorithm combines multiple decision trees to make more accurate predictions. Each decision tree in the random forest examines different random subsets of the data. The results from these trees are then combined via majority voting for classification (to determine the final class) or by averaging the predictions for regression (Breiman, 2001). This approach helps improve accuracy and reduce errors. Another key aspect of RF is the depth of the trees. In most cases, the individual decision trees are grown to their full depth without any pruning, making them very complex and potentially prone to overfitting if considered independently. However, this risk is mitigated in RF because the trees are aggregated, and their combined predictions help prevent overfitting. The two common ensemble techniques used in random forests to improve the performance of models are (i) bootstrap aggregating (bagging) is a core principle behind random forests, and it helps improve model accuracy and robustness. Samples are trained based on different decision trees. After training, the predictions from all the trees are aggregated: for classification, the final class is determined by majority voting (i.e., the class chosen by most trees), and for regression, the predictions are averaged.

Formula (Majority voting in random forest) (Equation 10):

Where:

● I (yb = c)is an indicator function that returns 1 if yb=c and 0 otherwise,

● B is the number of trees in the forest.

(ii) boosting, on the other hand, focuses on reducing bias by sequentially training models. Each new tree in a boosting algorithm is trained to correct the mistakes made by the previous trees, with more attention given to misclassified data points. The final prediction is a weighted combination of the trees’ outputs, where trees with better performance have more influence. The other boosting techniques like gradient boosting machine (GBM), extreme gradient boosting machine (XGBM), LightGBM, and CatBoost become essential to confront the machine learning more deliverable with accuracy and precision.

Research application

In vitro propagation is an essential technique for conserving and mass-producing economically valuable plant species, yet it faces persistent challenges such as low germination rates, contamination, and genotype-specific responses. For instance, the in vitro germination of Cannabis sativa, historically difficult due to low germination and high contamination, was optimized using five ML models. Random Forest (RF) outperformed others with F1 scores between 0.98–1.00, identifying an optimal hydrogen peroxide concentration of ~2.2% (Aasim et al., 2022). Similarly, in aquatic plants like Hemianthus callitrichoides, RF and MLP models demonstrated high accuracy in predicting growth based on media composition (Özcan et al., 2023). In Passiflora caerulea, RF and GRNN, coupled with genetic algorithms (GA), successfully modeled shoot regeneration, identifying a precise hormonal combination for optimal results (Jafari and Daneshvar, 2023). Furthermore, in Punica granatum, RF and XGBoost, supported by novel tools like the global performance indicator (GPI) and NSGA-II, showed high fidelity in shoot proliferation predictions (Zarbakhsh et al., 2024). Finally, ML applications in drought-stressed Fragaria × ananassa highlighted genotype-specific modeling, with RF achieving the highest overall accuracy (Şimşek, 2024). Collectively, these examples underscore the versatility and predictive power of ML, particularly RF and other machine learning algorithms, in optimizing tissue culture protocols across diverse species.

2.2 Unsupervised learning

Unsupervised learning is a type of machine learning that works with unlabeled data. These algorithms are designed to identify patterns and relationships within the data on their own, without any prior knowledge of what the data represents (Nasrabadi, 2007). There are three primary types of unsupervised learning algorithms. (i) Clustering algorithms group data points based on similarity to uncover patterns without predefined labels. Common methods include K-means, which partitions data into K-clusters based on distance; hierarchical clustering, which creates a tree-like structure of nested clusters; and density-based clustering (DBSCAN) which identifies dense regions while treating sparse points as noise. Mean-shift clustering shifts points toward high-density areas to form clusters, while spectral clustering uses graph theory to group data based on relationships between points. (ii) Association rule learning identifies relationships between variables in large datasets, commonly used in market basket analysis to find items frequently purchased together. Key algorithms include Apriori, which iteratively finds frequent item sets, which improves efficiency by avoiding candidate generation; and Eclat, which uses set intersections. (iii) Dimensionality reduction techniques reduce the number of features in a dataset while preserving meaningful information, improving model simplicity, computational efficiency, and visualization. Principal component analysis (PCA) transforms data into uncorrelated components that capture maximum variance, while linear discriminant analysis (LDA) finds projections that enhance class separability (Tipping and Bishop, 1999; Hastie et al., 2009b) (Figure 2B).

Research application

A high-throughput phenotyping method was developed to efficiently collect trait data using imaging systems during key crop growth stages. To reduce dependence on human-labeled data for image-based trait extraction, KAT4IA is introduced, a self-supervised learning pipeline that applies K-means clustering to greenhouse images to automatically generate training data for field-based phenotyping (Guo et al., 2021). Metabolomics was integrated with transcriptomic analysis, to detect metabolic responses to combined stress in Medicago truncatula. LC-HRMS data from roots and leaves were analyzed using the gaussian process 2-sample test, K-means clustering, and affinity propagation for temporal clustering. Results revealed known stress markers, including altered sucrose and citric acid levels, with combined stress amplifying drought effects. While leaf responses were more pronounced, fusarium-related changes were also observed in roots (Dickinson et al., 2018).

2.3 Reinforcement learning

Reinforcement learning is a branch of machine learning where an agent learns to make decisions by interacting with an environment to maximize cumulative rewards over time. The agent observes the current state, takes actions, and receives feedback in the form of rewards, adjusting its strategy, or policy, to improve future outcomes (Szepesvári, 2010). A central challenge in RL is balancing exploration (trying new actions) and exploitation (leveraging known rewarding actions). This process is often modeled using markov decision processes (MDPs), which define states, actions, transition probabilities, and rewards. There are several categories of RL algorithms. Value-based methods, such as Q-learning and state-action-reward-state-action (SARSA), focus on estimating value functions that predict the expected future rewards of actions taken in given states (Watkins and Dayan, 1992). More recently, deep reinforcement learning leverages neural networks to handle complex, high-dimensional environments, with algorithms such as deep Q-networks (DQN) and proximal policy optimization (PPO) achieving state-of-the-art results. Overall, reinforcement learning provides a powerful framework for training agents to make sequential decisions in uncertain and dynamic environments (Hastie et al., 2009b) (Figure 2C).

Research application

The use of RL in plant biology and agriculture presents a promising avenue for addressing both fundamental biological questions and applied agricultural challenges. Across three distinct domains, plant organ development, crop breeding, and field management, RL has demonstrated its versatility and effectiveness as a decision-making and optimization framework and yet be expanded in the field of plant tissue culture. The reinforcement learning was used to model the biomechanics of the “searcher shoot”, a plant organ specialized for spatial exploration. By framing mass distribution and structural constraints as a markov decision process (MDP), the authors created the Searcher-Shoot environment to simulate adaptive growth strategies. Results showed consistent shoot tapering, suggesting that plants may naturally adopt efficient mass allocation to optimize elongation without surpassing stress limits. The close match between simulated and empirical data highlights the potential of RL to model the adaptive complexity of plant morphology (Nasti et al., 2024). RL was applied to crop breeding, a domain challenged by slow generation turnover, high-dimensional decision spaces, and increasing environmental pressures due to climate change. By introducing a suite of Gym environments tailored for breeding simulations, the authors trained RL agents to make selection and crossing decisions based on real-world genomic data (Younis et al., 2024). In a parallel application, Balderas et al. (2025) examined RL’s potential in optimizing crop production management. Using the gym-DSSAT environment, a well-established crop simulation framework, they evaluated two widely used RL algorithms, proximal policy optimization (PPO) and deep Q-networks (DQN), across key agricultural tasks: fertilization, irrigation, and integrated management. Their findings revealed that PPO generally performed better in single-task settings (fertilization and irrigation), whereas DQN excelled in the mixed management task.

2.4 Semi-supervised learning

Semi-supervised learning is a hybrid approach that lies between supervised and unsupervised learning, combining both labeled and unlabeled data. This method is particularly useful when labeled data is scarce or expensive to obtain, but a large amount of unlabeled data is available, helping to improve model performance through various strategies (Zhu and Goldberg, 2009). Self-training iteratively labels unlabeled data using an initial model trained on labeled data. Co-training leverages multiple classifiers, each trained on different data views, to label unlabeled examples. Generative models, like gaussian mixture models (GMMs) and hidden markov models (HMMs) predict labels based on learned data distributions (Hastie et al., 2009b) (Figure 2D).

Research application

Pure self-supervised learning (SSL) methods, like FixMatch and others, haven’t been widely adopted in plant tissue culture research. This is largely because of the small dataset sizes and the challenges in reliably generating pseudo-labels for in-vitro outcomes. Instead, most recent studies have focused on label-efficient models, approaches that combine regression or classification techniques with limited experimental data or utilize self- and semi-controlled setups. A semi-supervised framework, DM_CorrMatch, was proposed for rapeseed inflorescence segmentation. It integrates data augmentation with a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) to address limited annotated data. The Mamba-Deeplabv3+ network used in the study captures both local and global features, enhancing segmentation accuracy despite complex backgrounds and variable inflorescence poses. Validated on the rapeseed flower segmentation dataset (RFSD), the model achieved an intersection over union (IoU) of 0.886, precision of 0.942, and recall of 0.940 (Li et al., 2025). A study focused on plant leaf disease recognition using semi-supervised few-shot learning approach was carried out to address the challenge of limited labeled data in plant pathology. By combining source and target domains from the PlantVillage dataset, the iterative semi-supervised method achieved an accuracy improvement of up to 4.6% (Li and Chao, 2021). Najafian et al. (2023) explored the use of deep learning for semantic segmentation in agriculture with minimal annotation. By applying domain adaptation techniques, the authors achieved impressive segmentation results for wheat heads with just two annotated images, demonstrating the power of synthesized datasets and the effectiveness of using limited labeled data.

3 Artificial neural networks in plant tissue culture

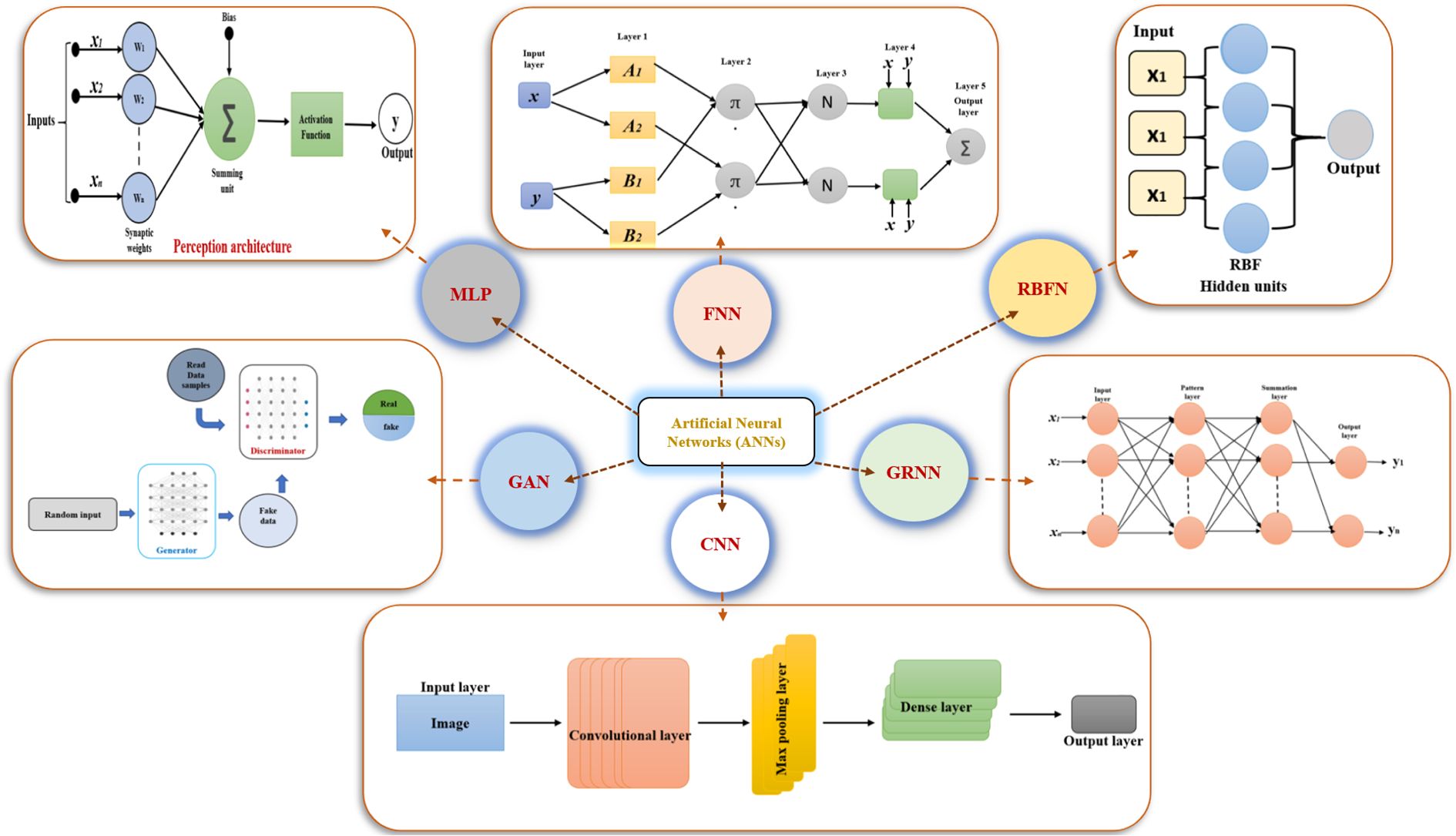

Artificial neural networks have been extensively applied in plant tissue culture to predict, analyze, and optimize processes including plant growth, tissue regeneration, callus formation, and disease detection (Prasad and Gupta, 2008) (Table 2). Several types of ANNs can be employed for different purposes in plant tissue culture research (Figure 3). Some of the most common types include.

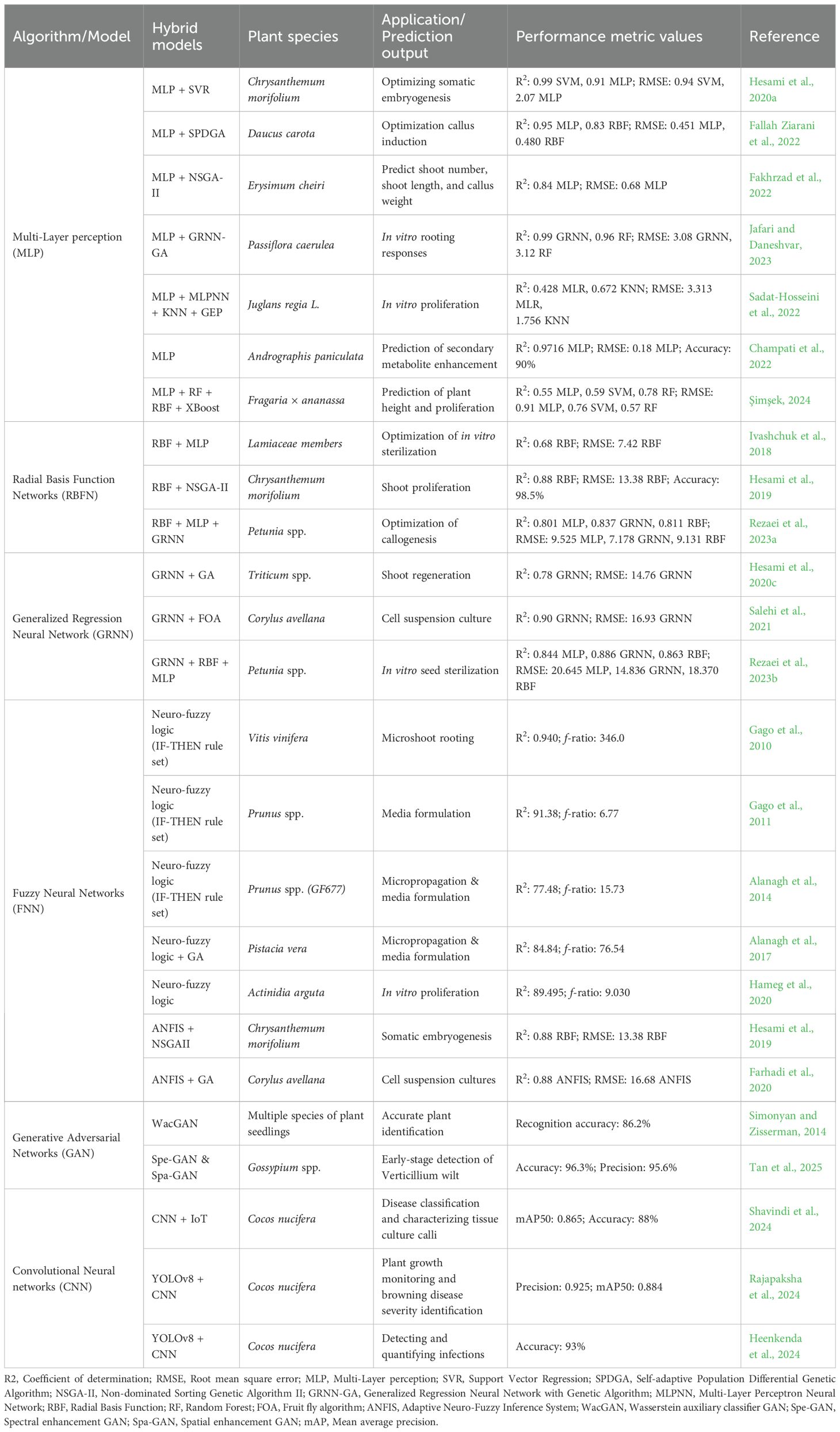

Table 2. Applications of artificial neural networks (ANNs) approaches/models used in plant tissue culture and other prediction studies.

Figure 3. Architectural variants of artificial neural networks (ANNs). MLP, Multilayer Perceptron; FNN, Fuzzy Neural Network; RBFN, Radial Basis Function Network; GAN, Generative Adversarial Network; CNN, Convolutional Neural Network; GRNN, General Regression Neural Network.

3.1 Multi-layer perception

A Multi-layer perceptron is consisting of fully connected layers that transform input data through various dimensions. It is called “multi-layer” because it includes an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. The input layer contains neurons representing each feature in the data, while the hidden layers process the information passed from the input. The number of hidden layers and neurons in each can vary. Finally, the output layer generates the prediction or result, with a number of neurons corresponding to the number of outputs. The main purpose of an MLP is to model complex relationships between inputs and outputs (Christopher, 1995). Each neuron in the hidden layers processes the input by first calculating a weighted sum of the inputs, given by the formula (Equation 11).

Where xi is the input feature, wi is the corresponding weight and b is the bias term. This weighted sum z, is then passed through an activation function to introduce non-linearity. Once the network generates an output, the next step is to compute the loss using a loss function, which compares the predicted output to the actual label. For a classification task, the binary cross-entropy loss function is typically used (Equation 12):

where yi is the actual label, is the predicted label, and N is the number of samples.

For regression problems, mean squared error (MSE) is often used (Equation 13):

Where is the average label value at node t, ∣t∣ is the number of samples at node t.

The goal of training an MLP is to minimize the loss function by adjusting the network’s weights and biases through backpropagation. MLPs use optimization algorithms to iteratively update weights and biases during training. Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) updates weights using individual samples or small batches, while the Adam optimizer enhances SGD by incorporating momentum and adaptive learning rates, enabling more efficient and effective training through dynamic adjustment of learning rates (Osama et al., 2015).

Research application

The critical role of optimizing somatic embryogenesis for successful gene transformation in chrysanthemum was analyzed by comparing two ML models, multilayer perceptron (MLP) and support vector regression (SVR). The study found that SVR outperformed MLP, achieving a higher predictive accuracy (R² > 0.92 vs. R² > 0.82). When combined with the NSGA-II optimization algorithm, the SVR model led to exceptional results including 99.09% embryogenesis efficiency and an average of 56.24 embryos per explant. This study highlighted the potential of integrating machine learning with evolutionary algorithms to enhance plant tissue culture outcomes (Hesami and Jones, 2020b). Similarly, Fallah Ziarani et al. (2022) employed an MLP model integrated with a single point discrete genetic algorithm (SPDGA) to optimize callus induction in carrots. The MLP model outperformed the radial basis function (RBF) network, achieving R² values around 0.95. Sensitivity analysis revealed MS-salt concentration as the most influential factor, underscoring the value of targeted ML optimization in improving regeneration protocols. In Erysimum cheiri, a lesser-studied medicinal plant, Fakhrzad et al. (2022) developed MLP-based models to predict shoot number, shoot length, and callus weight, with strong predictive performance (R²=0.84–0.99). Optimization using NSGA-II helped fine-tune hormone concentrations, further validating the reliability of the model. A focused study on rooting in Passiflora caerulea, was carried out by applying a hybrid general regression neural network–genetic algorithm (GRNN-GA) model (Jafari and Daneshvar, 2023). This study demonstrated the GRNN-GA model’s effectiveness in capturing complex in vitro rooting responses. GRNN achieved excellent accuracy (R² > 0.92), and the optimization process produced favorable rooting outcomes based on auxin types and explant sources. The application of MLP-based artificial neural network was successful to correlate soil nutrient levels with andrographolide content in Andrographis paniculata across 150 accessions in eastern India (Champati et al., 2022). Their best-performing model (14-12–1 architecture) achieved a high accuracy (R² = 0.9716), and the optimization process raised andrographolide content from 3.38% to 4.90%. This study showcased the broader utility of ML in site selection and secondary metabolite enhancement, extending its value beyond traditional tissue culture. Sadat-Hosseini et al. (2022) compared multiple ML models, including MLPNN, K-nearest neighbors (KNN), and gene expression programming (GEP), against traditional multiple linear regression (MLR) for predicting in vitro proliferation in persian walnut (Juglans regia). GEP, particularly when optimized with particle swarm optimization (PSO), provided the most accurate predictions (R² = 0.802 for the ‘chandler’ cultivar, significantly outperforming MLR (R² = 0.412). The study also validated KNN as a simple yet effective tool, highlighting the range of viable ML approaches depending on data complexity and application needs. Şimşek (2024) extended ML applications to genotype-specific optimization in lavender and strawberry cultivars. In lavender, random forest (RF) outperformed other models (MLP, RBF, XGBoost, and Gaussian process) in predicting root traits, particularly for the ‘Festival’ and ‘Fortuna’ genotypes. Meanwhile, MLP and GP models were more effective in predicting traits for ‘Rubygem’. Similarly, in strawberries under PEG-induced drought stress, RF achieved the highest accuracy (91.16%) for root trait prediction, while MLP and GP better predicted plant height and proliferation. These findings emphasize the need to tailor model selection to genotype and trait specificity.

3.2 Radial basis function networks

Radial basis function network is designed primarily for tasks such as function approximation, classification, and regression. This is particularly effective for problems where the relationship between input and output is nonlinear. At their core, RBFN is a form of feedforward neural network consisting of three layers: the input layer, which receives the input features; the hidden layer, which contains radial basis function neurons that transform the input into a higher-dimensional space; and the output layer, which generates the final output after the transformation (Lin et al., 2020a). A radial basis function is a real-valued function whose output depends only on the distance between the input and a specific point (often referred to as a center). The output of the function is maximum at the center and decreases as the input moves farther away from it.

The output of the network can be expressed as (Equation 14):

Where:

y(x) the output of the network, wi are the weights between the hidden neurons and the output layer, ϕ(∥x−ci∥, σi) is the output of the radial basis function at neuron i, ci is the center of the ith radial basis function, σi is the spread (or width) of the ith radial basis function.

Commonly, optimization algorithms like gradient descent, least squares, or LMS (Least mean squares) are used to minimize the error between the predicted and actual outputs.

Research application

Ivashchuk et al. (2018) applied neural networks to model and optimize the sterilization stage for plant seeds, specifically targeting rare and medicinal plants. The study used both MLP and RBF networks to predict the optimal sterilization parameters (sterilant type, concentration, and exposure time). The combination of radial basis function (RBF) networks and the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm-II (NSGA-II) was used to model and optimize the medium compositions for shoot proliferation in chrysanthemum (Hesami et al., 2019). The study is focused on four outputs, proliferation rate (PR), shoot number (SN), shoot length (SL), and basal callus weight (BCW), based on the concentrations of four variables: BAP, IBA, phloroglucinol (PG), and sucrose. The results showed high prediction accuracy with R² values of 0.88, 0.91, 0.97, and 0.76 for PR, SN, SL, and BCW, respectively. Importantly, the predicted and actual outcomes showed negligible differences, validating RBF-NSGAII as a reliable and efficient tool for optimizing in vitro organogenesis. Rezaei et al. (2023a) focused on the optimization of callogenesis in petunia by developing a predictive model using three machine learning algorithms: multilayer perceptron (MLP), radial basis function (RBF), and generalized regression neural network (GRNN). The goal was to optimize the concentrations of phytohormones to enhance callus formation rate (CFR) and callus fresh weight (CFW). Among the models, GRNN outperformed MLP and RBF with R² values of ≥83%. The study also employed sensitivity analysis, which revealed that IBA was the most influential phytohormone for callogenesis. By integrating GRNN with a genetic algorithm (GA), the study identified an optimized set of phytohormone concentrations that maximized CFR to 95.83%. Experimental validation confirmed the accuracy of the predicted optimal conditions, showing no significant difference between the experimental and GA-predicted results. This approach demonstrates the successful integration of machine learning, sensitivity analysis, and genetic algorithms to optimize tissue culture conditions in a controlled and efficient manner.

3.3 Generalized regression neural network

The generalized regression neural network is a special form of radial basis function (RBF) networks and functions as a non-parametric, memory-based model that provides a smooth approximation of the underlying relationship between inputs and outputs. One of its main advantages is its ability to approximate any arbitrary function directly from training data without requiring an assumed functional form. GRNN consists of four layers: the input layer, which contains neurons representing the features of the input vector and simply passes the data forward without processing; the pattern layer (or radial basis layer), where each neuron corresponds to a training sample and calculates the euclidean distance between the input and that sample, then applies a gaussian kernel to convert this distance into a similarity measure (Equation 15).

Where x is input vector, xi is training sample vector and σ is smoothing parameter (spread or bandwidth).

This structure allows GRNN to provide smooth and effective regression estimates directly from the data, making it a powerful tool for nonlinear function approximation (Specht, 1991).

Research application

Hesami et al. (2020c) used GRNN-GA to model shoot regeneration in wheat, addressing genotype-dependent variability. Based on 10 input variables, GRNN-GA achieved good predictive performance (R² = 0.78) and identified 2,4-D, explant type, and genotype as key factors, supporting more efficient, genotype-independent regeneration protocols. A cost-effective method for paclitaxel production in Corylus avellana was demonstrated using cell suspension culture (CSC) enhanced by fungal elicitors (Salehi et al., 2021). In this study, a general regression neural network optimized by the fruit fly algorithm (GRNN-FOA) was applied to predict and optimize paclitaxel biosynthesis and biomass production, using four input variables: cell extract (CE), culture filtrate (CF), elicitor adding day, and harvesting time. GRNN-FOA showed higher accuracy (R² = 0.88–0.97) than traditional regression (R² = 0.57–0.86), and performed comparably to MLP-GA, with slight advantages for MLP-GA in total and extracellular paclitaxel prediction. GRNN-FOA optimization predicted a maximum paclitaxel yield of 372.89 µg L-¹ under specific conditions, closely matching observed values, validating its potential in optimizing secondary metabolite production in vitro. Rezaei et al. (2023b) evaluated six disinfectants and immersion times on Petunia seed sterilization and germination. Among MLP, RBF, and GRNN models, GRNN performed best. They applied NSGA-II for multi-objective optimization, demonstrating that GRNN-NSGA-II effectively balances contamination control and germination success, offering a robust tool for plant tissue culture optimization.

3.4 Fuzzy neural networks

Neuro-fuzzy logic is a hybrid system that integrates neural networks with fuzzy logic principles to solve complex problems involving uncertainty and imprecision. By combining the learning capabilities of neural networks with the reasoning power of fuzzy logic, it proves especially effective in fields such as control systems, pattern recognition, decision-making, and adaptive systems (Ishibuchi, 1996). Unlike classical logic, where variables are strictly true or false, fuzzy logic allows for a continuum of truth values between 0 and 1. This approach enables systems to model fuzzy rules while simultaneously learning from data. The system operates through four main steps (i) fuzzyfication, where input data is transformed into fuzzy values using membership functions (ii) rule formation, where fuzzy rules describe input-output relationships and can adapt automatically during learning (iii) adaptive learning, where the neural network adjusts the fuzzy rule parameters, like membership functions and rule weights, using algorithms such as backpropagation to minimize errors; and finally, (iv) defuzzification, where fuzzy outputs are converted into crisp values through methods like the centroid technique. Various neuro-fuzzy system implementations exist, notably the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS), known for its efficiency in function approximation. Another approach, the Fuzzy Neural Network (FNN), combines fuzzy logic with neural networks and often uses Mamdani-type rules, which enhance interpretability but increase computational cost. Additionally, Fuzzy C-Means, to partition the input space into clusters, enabling more effective decision-making by training neural networks on these fuzzy clusters (Talpur et al., 2023).

Research application

Recent advances in plant tissue culture optimization increasingly utilize AI, particularly neuro-fuzzy systems and hybrid models combining with evolutionary algorithms, to model complex relationships and enhance culture protocols. Initially, Gago et al. (2010) applied neuro-fuzzy logic to grapevine microshoot rooting, uncovering interactions, such as auxin-sucrose effects, not previously identified by statistical methods. This deepened the understanding of the micropropagation process and demonstrated the rapid applicability of AI modeling. The effective application of neuro-fuzzy logic to mine apricot micropropagation databases has revealed meaningful IF-THEN rules linking cultivars, mineral nutrients, and plant growth regulators with growth parameters (Gago et al., 2011). Their approach validated and extended traditional statistical findings by generating interpretable, reusable knowledge that supports future media optimization. In line with these applications, Alanagh et al. (2014) employed neuro-fuzzy logic to model macronutrient effects on GF677 peach × almond rootstock micropropagation. Their model pinpointed key ion interactions, such as NO3− × Ca2+, that significantly affect shoot quality and development, providing a powerful tool to infer optimal nutrient combinations and mitigate physiological disorders like hyperhydricity. Neuro-fuzzy logic and hybrid AI techniques to dissect nutrient and growth regulator influences on pistachio (Pistacia vera) micropropagation was given by Alanagh et al. (2017). By reducing complex media component combinations via design of experiments (DOE) and applying AI modeling, they uncovered critical ion interactions affecting shoot proliferation, quality, and physiological disorders, enabling more rational design of culture media. Hameg et al. (2020) applied neurofuzzy logic to kiwi (Actinidia arguta) micropropagation, revealing that BAP concentration predominantly influences shoot number, while a combination of BAP and GA3 affects shoot length. Their model also underscored the importance of the number of subcultures and media composition, highlighting AI’s role in interpreting multifactorial effects and guiding protocol refinement. Similarly, Hesami et al. (2019) introduced a hybrid adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system combined with the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm-II (ANFIS-NSGAII) for modeling somatic embryogenesis in chrysanthemum. Their results showed high predictive accuracy (R² > 92%) and identified optimal media compositions and light conditions to maximize embryogenesis frequency and somatic embryo number. Sensitivity analysis further highlighted 2,4-D as a critical factor, illustrating how hybrid AI models can guide precise optimization in complex biological systems. Farhadi et al. (2020) modeled paclitaxel production in Corylus avellana cell suspension cultures using ANFIS combined with genetic algorithms. Their model outperformed traditional regression approaches and successfully predicted optimal elicitor and methyl-β-cyclodextrin concentrations and timing to maximize paclitaxel yield, showcasing AI’s utility in bioproduct optimization.

3.5 Generative adversarial networks

Generative adversarial networks are a class of machine learning frameworks designed to generate new data instances that resemble a given dataset. They consist of two neural networks, the generator and the discriminator, that are trained simultaneously in a competitive setting. The unique aspect of GANs lies in their adversarial nature, where the generator creates data, and the discriminator tries to distinguish between real and fake data. Over time, as these networks “battle,” the generator learns to produce increasingly convincing data, while the discriminator improves its ability to differentiate between real and fake samples. As this adversarial process continues, both networks improve iteratively, with the generator producing more realistic data and the discriminator becoming more adept at distinguishing the two (Goodfellow et al., 2020).

Research application

Madsen et al. (2019) addressed the challenge of high intra-class variance and low inter-class variance in plant seedlings, an issue that hinders accurate plant identification using deep learning. To mitigate limited training data, they employed generative adversarial networks (GANs) to generate synthetic images across nine plant species. While the GAN-augmented model reached high recognition accuracy, misclassifications arose mainly during the dicotyledonous growth stage, where visual similarities between species and subtle shape differences confused the model. Notably, the synthetic data proved effective for pretraining a classification model, which performed well even before fine-tuning. Further fine-tuning with real data yielded only marginal improvement, indicating the robustness of the pretrained model. The early detection challenges of verticillium wilt (VW) in cotton, was addressed as a major concern for cotton yields globally (Tan et al., 2025). The study proposed an innovative method integrating GANs with hyperspectral imaging to enhance early-stage detection. Two models, Spe-GAN (spectral enhancement) and Spa-GAN (spatial enhancement), were developed to capture subtle symptoms of VW, a task complicated by limited data. The results showed that these GAN-based models significantly outperformed traditional machine learning (RF, SVM) and deep learning methods (LSTM, ResNet18), with Spe-GAN achieving 94.52% accuracy and Spa-GAN 91.78%. The approach’s success was largely attributed to its ability to augment limited data and enhance model interpretability, offering a new approach for early disease detection in cotton and potentially other plants.

3.6 Convolutional neural networks

A convolutional neural network is designed specifically for processing grid-like data, such as 2D images. Unlike fully connected neural networks (FCNs), CNNs use local receptive fields and shared weights to extract spatial hierarchies of features through convolutions. The input layer, is typically a 3D tensor (height × width × channels). Convolutional Layer, applies a number of filters (kernels) that scan across the input image to extract feature maps (Simonyan and Zisserman, 2014). A filter is a small matrix that slides over the input, performing element-wise multiplication and summing the results to form a single output value per position. Parameters include stride (the number of pixels the filter moves across the image) and Padding (Adding zero borders to control the spatial size of the output). In CNNs, pooling layers perform down sampling to reduce the spatial dimensions of feature maps, lowering computational complexity and helping to prevent overfitting. Max pooling is the most common method, selecting the maximum value within a local window to preserve dominant features. After several convolution and pooling stages, the network transitions to fully connected layers, where flattened feature maps are used for high-level reasoning. The final output layer, also fully connected, uses activation functions suited to the task, softmax for multi-class classification and sigmoid for binary or multilabel classification.

Research application

The integration of deep learning, image processing, and IoT technologies in coconut tissue culture monitoring, as demonstrated by Shavindi et al. (2024), presents a transformative shift in agricultural biotechnology. By automating the classification of callus tissues and enabling continuous culture monitoring, the study addresses critical inefficiencies in traditional tissue culture methods. Complementing this work, Rajapaksha et al. (2024) focused on automating the measurement of plant growth parameters using deep learning models, particularly YOLOv8 and CNN architectures. Their research achieved high accuracy in tasks such as flask detection (precision: 0.990, mAP@50: 0.995), leaf and stem segmentation, and root classification. Moreover, InceptionV3 achieved 96% accuracy in browning disease classification, demonstrating the potential of CNNs in plant health diagnostics. Heenkenda et al. (2024) further highlighted the limitations of conventional tissue culture techniques, especially in early disease detection. Their proposed machine learning-based approach for identifying and predicting bacterial and fungal infections through image analysis offers a critical advancement. The integration of technological tools with agronomical expertise bridges the gap between traditional farming practices and modern precision agriculture, fostering sustainable cultivation and timely disease management.

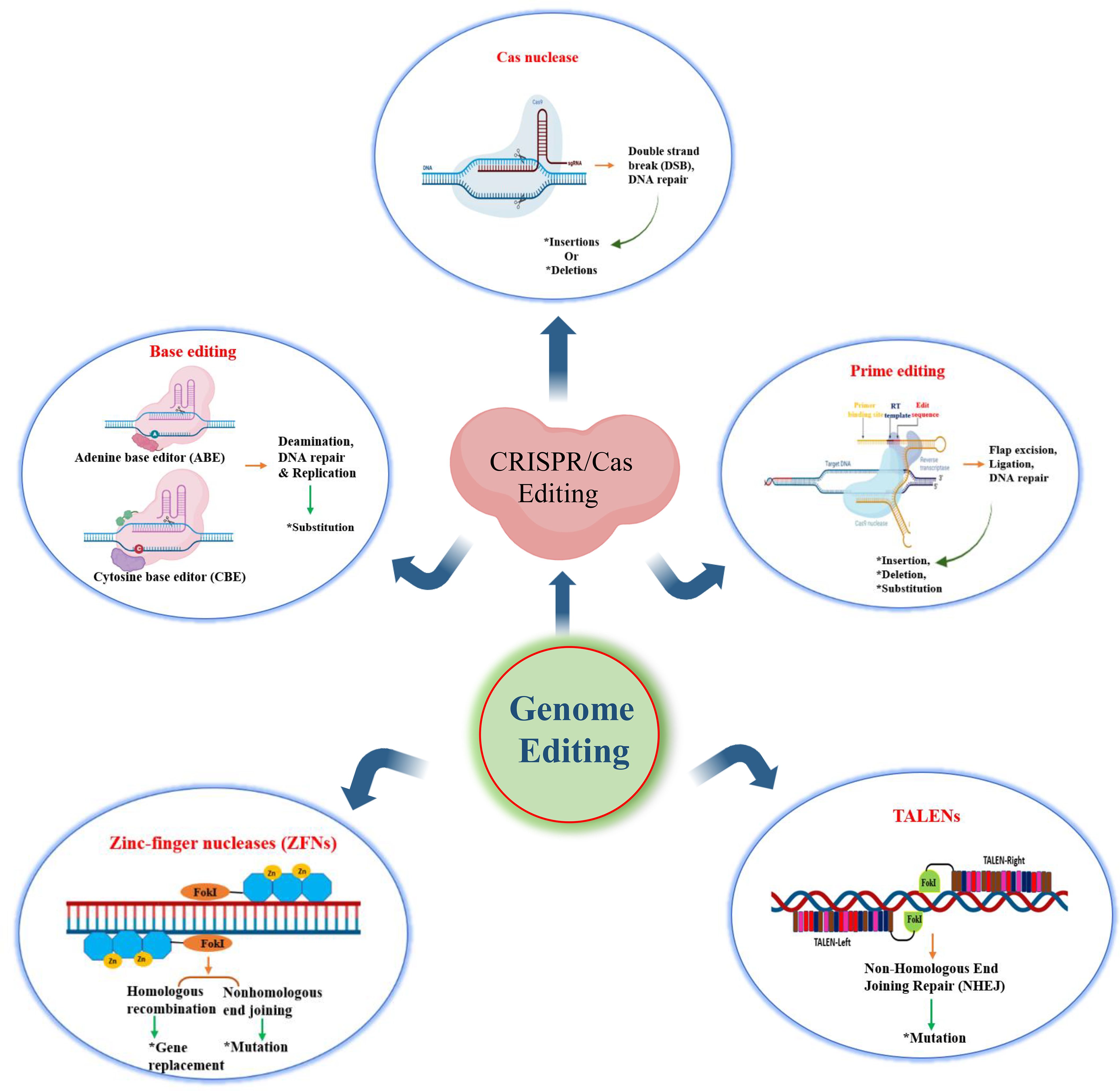

4 Advancements in genome editing technologies

Genome editing is a revolutionary technology that enables precise modifications to an organism’s DNA, including insertions, deletions, and replacements, to modify biological traits. Several genome editing tools have been developed, each with distinct mechanisms and limitations. Meganucleases are natural endodeoxyribonucleases that recognize and cleave DNA sequences typically 20–30 base pairs long. Although their recognition sites can be re-engineered for site-specific editing, the structural complexity and time-consuming modification process have limited their widespread use (Ashworth et al., 2006; Grizot et al., 2009). Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) combine engineered zinc finger proteins with the FokI endonuclease to generate site-specific DNA breaks (Kim et al., 1996), while Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) use TALE-derived DNA-binding domains and FokI to induce targeted double-stranded breaks (DSBs) (Christian et al., 2010). Despite their proven efficacy, the intricate and labor-intensive design and assembly of meganucleases, ZFNs, and TALENs have restricted their adoption.

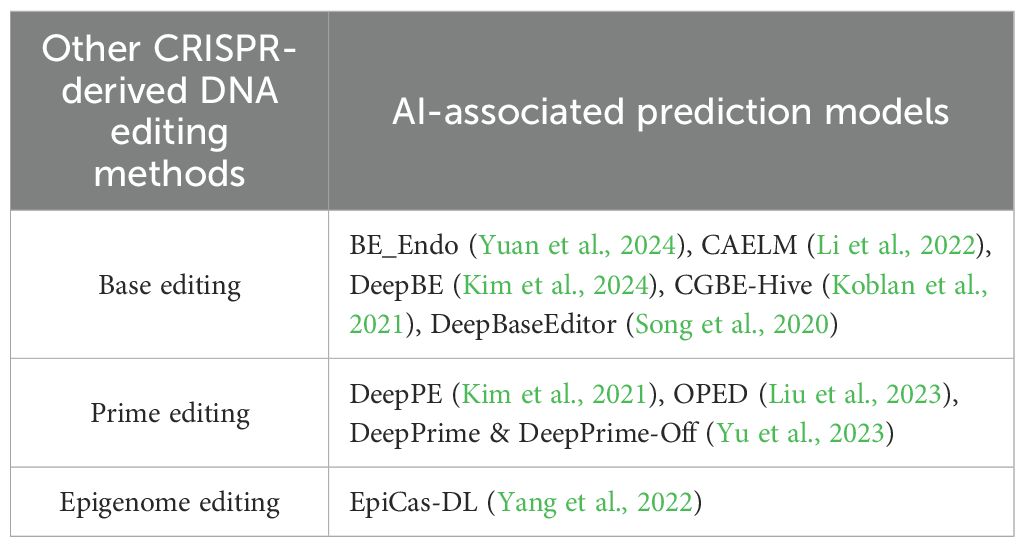

In contrast, CRISPR/Cas systems (Makarova et al., 2011), particularly CRISPR/Cas9 and CRISPR/Cas12a, have gained prominence due to their simplicity, flexibility, and efficiency. Originating as an adaptive immune system in bacteria and archaea, CRISPR/Cas uses guide RNAs to direct Cas proteins to specific DNA sequences adjacent to a PAM (protospacer adjacent motif), enabling targeted cleavage (Garneau et al., 2010). CRISPR/Cas systems introduce DSBs, which are repaired by either non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), an error-prone process leading to insertions or deletions or homology-directed repair (HDR), which allows precise gene correction using a template. Early CRISPR studies in plants demonstrated successful gene knockouts and modifications, highlighting its powerful potential in plant biology (Feng et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013; Nekrasov et al., 2013). Recent advancements include base editing and prime editing. Base editors combine a Cas9 nickase or dead Cas9 (dCas9) with a deaminase enzyme to convert specific nucleotides without inducing DSBs (Komor et al., 2016). Prime editors fuse dCas9 with reverse transcriptase and use a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) to direct edits at a target site through a templated reverse transcription mechanism (Anzalone et al., 2019). These next-generation tools have been successfully applied across various plant species, significantly advancing precision breeding and crop improvement (Lin et al., 2020b) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Overview of genome editing techniques: CRISPR/Cas and other nuclease-based approaches (This figure was drawn using free version of BioRender; https://www.biorender.com).

4.1 Searching and screening strategy

The identification phase involves constructing search queries using combinations of keywords, that include: “CRISPR EDITING USING MACHINE LEARNING”, “DEEP LEARNING AND CRISPR EDITING”, “MACHINE AND DEEP LEARNING AND CRISPR EDITING”. This study draws from multiple online databases like pubmed central, scopus and google scholar, compiling research on the application of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) in genome editing technologies. The articles were selected based on their relevance and uniqueness. Peer-reviewed research papers and review articles were considered for analysis. Initial screening was conducted at the abstract level, followed by data extraction and full-text analysis.

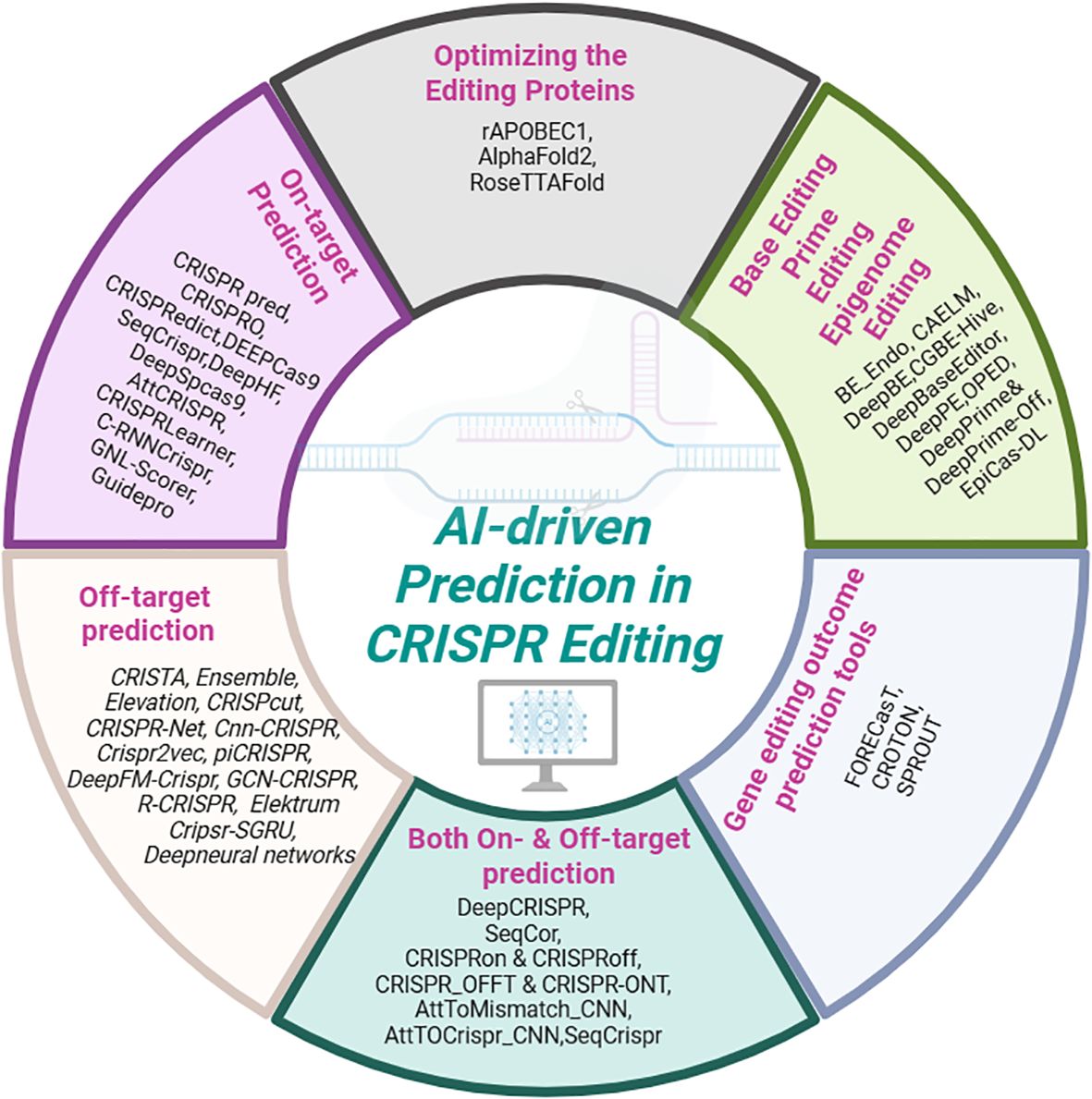

4.2 Role of machine learning/deep learning in CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing

The accuracy and accessibility of genome-editing tools particularly CRISPR-associated Cas9 protein has revolutionized the biological research and therapeutic development. A key objective is improving guide RNA (gRNA) design to enhance on-target efficiency (OTE) and minimize off-target effects (OFTE). This review explores recent advances in computational methods, particularly ML and DL, for predicting gRNA performance. It also highlights the role of AI in advancing base editing, prime editing and epigenome editing as well as discusses about tools for predicting gene editing outcome’s and optimizing editing proteins.

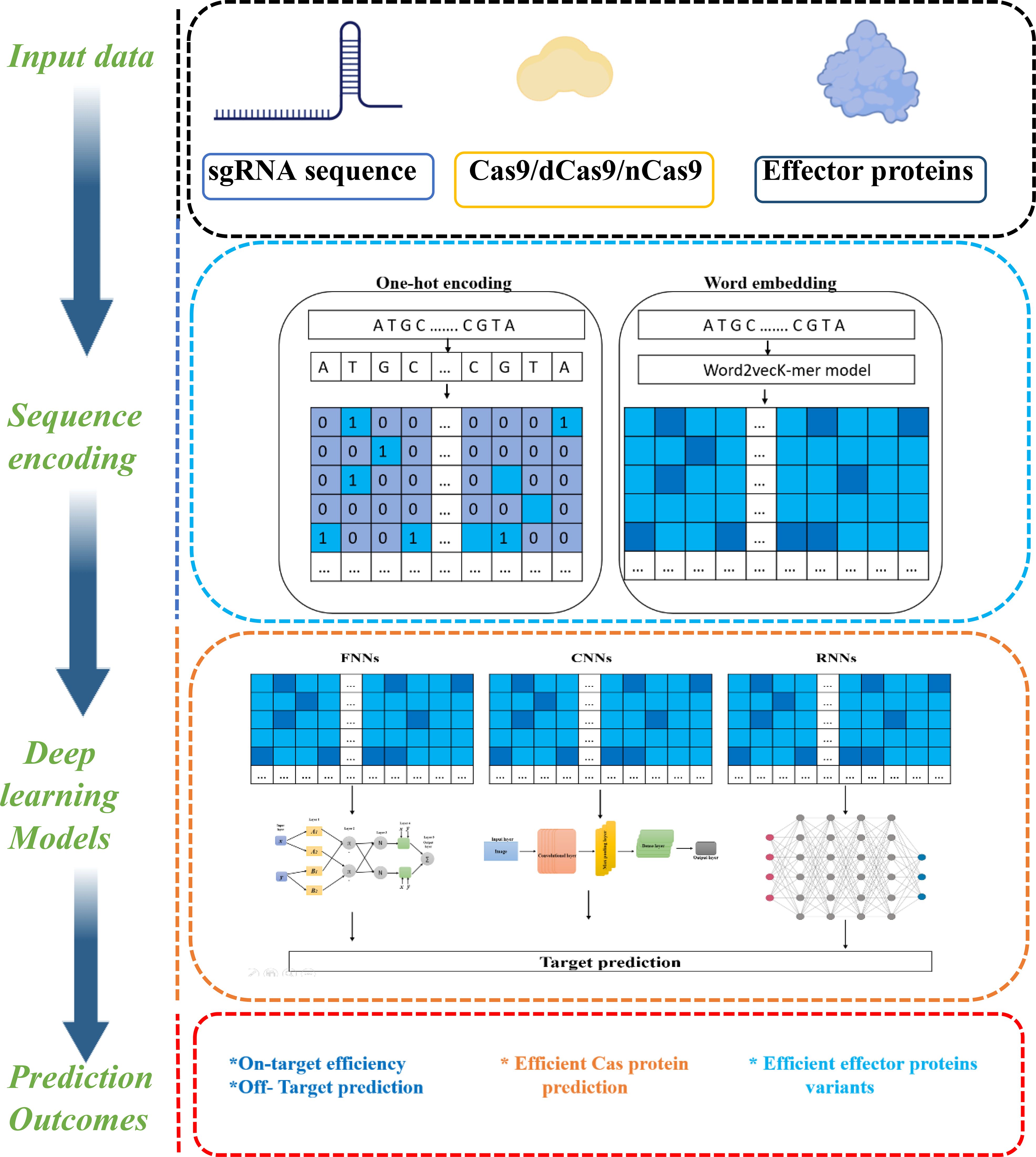

4.2.1 sgRNA-DNA sequence encoding

To serve as input for AI models, sgRNA–DNA sequence data must first undergo preprocessing, commonly referred to as “sequence encoding”. This step transforms nucleotide sequences, composed of letters (A, C, G, T), into numerical formats that ML and DL algorithms can process and interpret (Figure 5). Proper encoding is critical for enhancing predictive accuracy. The two most widely adopted encoding methods in CRISPR-Cas9 research are (i) In one-hot encoding, each nucleotide is represented as a binary vector; e.g., A = [1, 0, 0, 0], C = [0, 1, 0, 0]), forming a 4×L matrix for a sequence of length L. Chuai et al. (2018) introduced DeepCRISPR, augmenting the standard one-hot encoding to a (4+n)×23 matrix by appending n epigenetic features per position, optimized for convolutional denoising networks. Lin and Wong (2018) proposed a unified 4×23 matrix encoding both sgRNA and target DNA for use in feedforward and convolutional networks. Charlier et al. (2021) developed a bijective mapping combining separate 4×23 matrices into an 8×23 input for FNNs, CNNs, and RNNs. Zhang et al. (2020a) further expanded the encoding to a 20×L multi-channel matrix incorporating bulges and mismatches, improving off-target prediction with CNNs and data augmentation. (ii) Word embedding, by contrast, assigns each substring (or k-mer) a dense vector in a continuous space, capturing semantic or contextual relationships between sequences. A widely used embedding method is Word2Vec (Mikolov et al., 2013), a neural network-based technique originally developed for natural language processing. Liu et al. (2020a) combined word embedding with transformers, CNNs, and FNNs, achieving performance comparable to advanced one-hot methods. They later used GloVe to generate dense sgRNA vectors fed into bidirectional LSTM and CNN models, reaching state-of-the-art off-target prediction.

Figure 5. Schematics of deep learning framework for CRISPR-Cas system prediction using sequence encoding techniques (This figure was drawn using free version of BioRender; https://www.biorender.com).

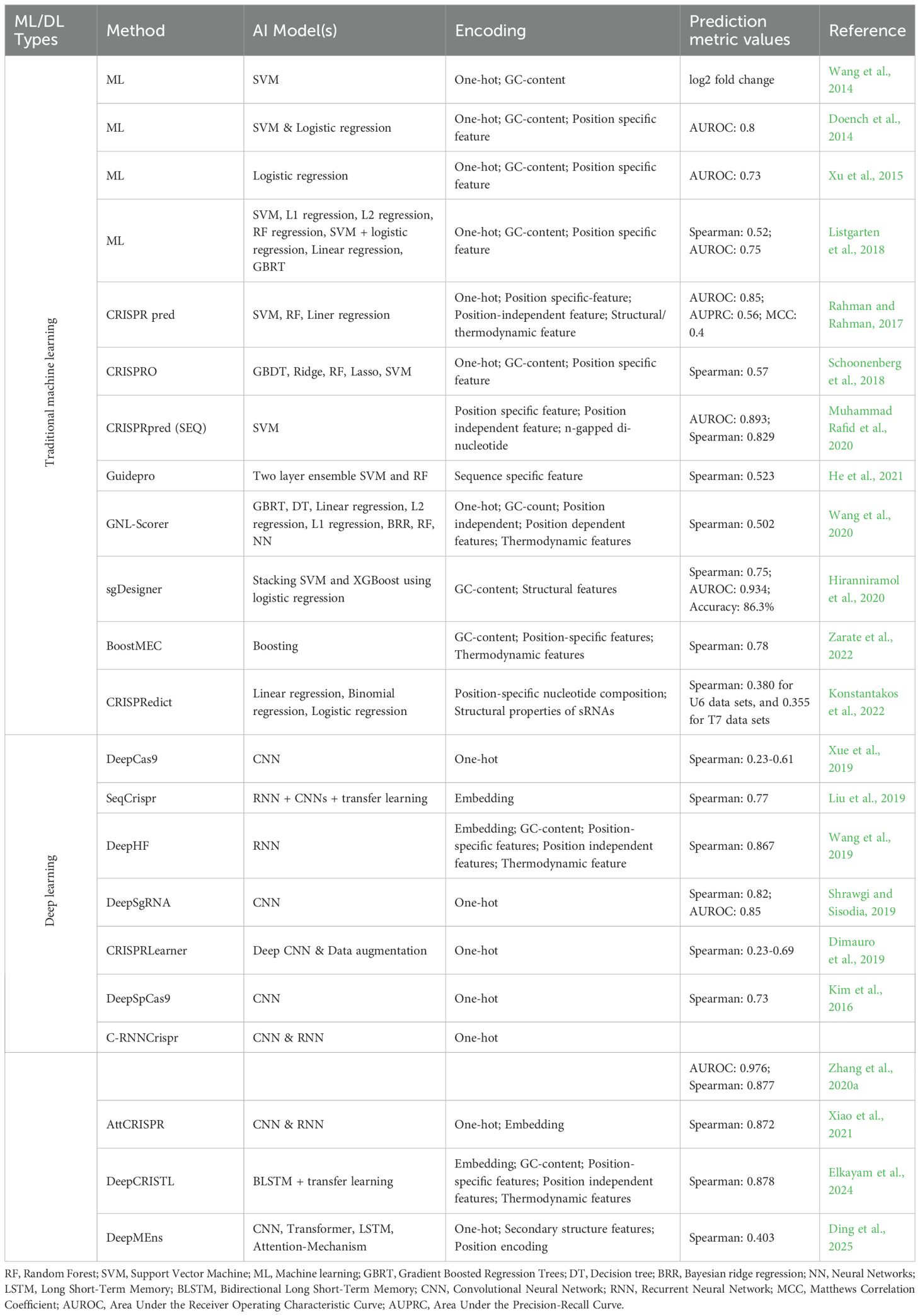

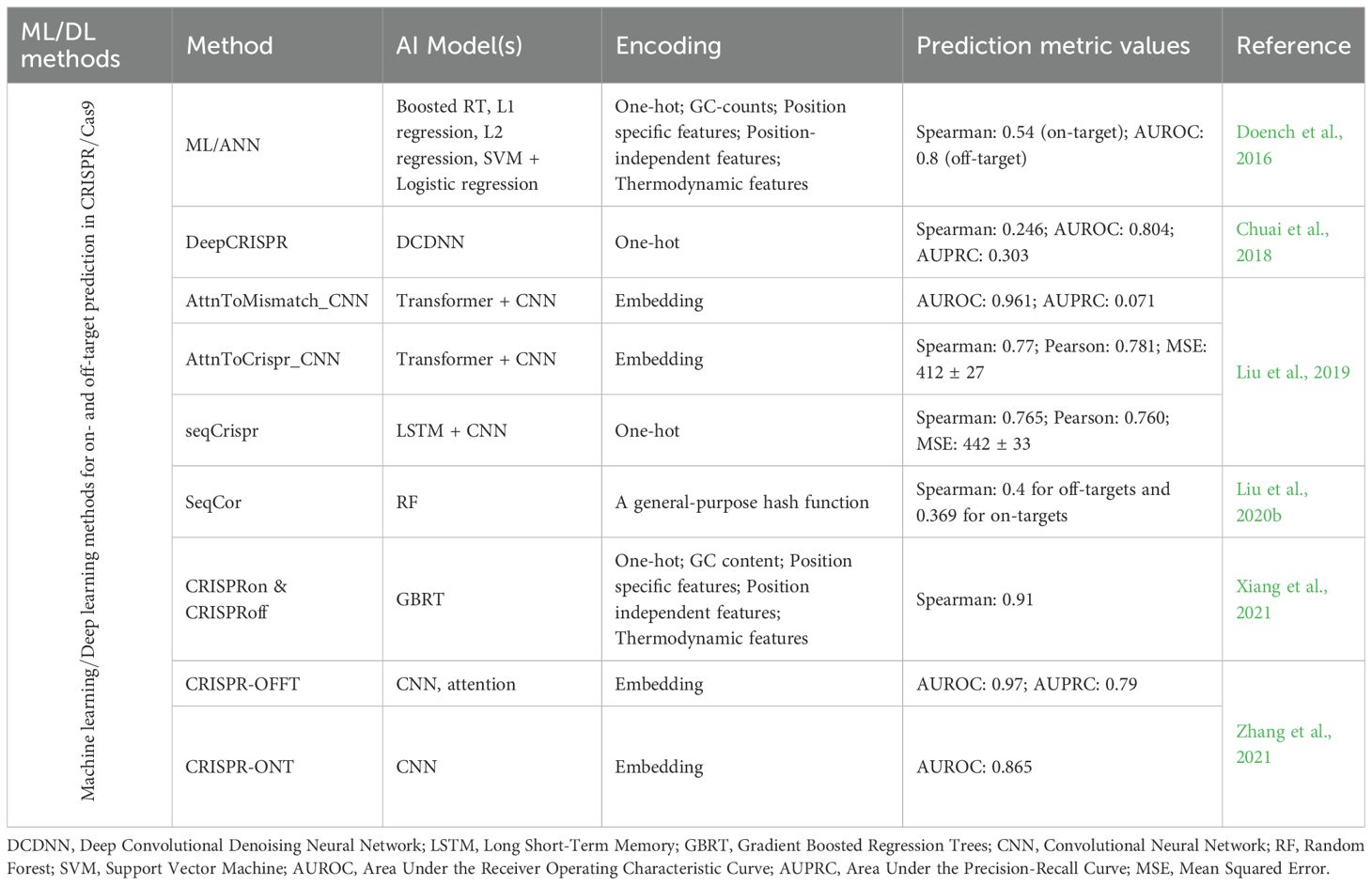

Beyond encoding, traditional ML models rely on engineered features such as nucleotide frequencies, GC content, thermodynamic properties (Doench et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2015), RNA secondary structure and n-gapped dinucleotides (Rahman and Rahman, 2017). Biological annotations like exon positions, amino acid traits, and domain occupancy also enhance predictions (Schoonenberg et al., 2018). Studies have highlighted the importance of positional and thermodynamic features, structural elements, accessibility, mismatch counts, and allele information (Muhammad Rafid et al., 2020). Statistical methods identify key predictors (Hiranniramol et al., 2020), and factors like frameshift probability and amino acid sensitivity improve sgRNA efficiency forecasts (He et al., 2021). Although deep learning models can automatically learn feature representations, manually engineered features remain essential for the performance of conventional machine learning models (Figure 6).

Figure 6. AI-driven prediction tools and applications in CRISPR genome editing (This figure was drawn using free version of BioRender; https://www.biorender.com). .

4.2.2 Off-target prediction in CRISPR/Cas9 editing

In CRISPR gene editing, the single guide RNA (sgRNA) directs the Cas9 protein to a specific genomic site for targeted modification. However, Cas9 can sometimes cleave unintended sites, leading to off-target effects that may disrupt gene sequences and interfere with normal gene function. These unintended effects are influenced by factors such as the structure and length of the sgRNA (Chao and Fei, 2023). Off-target effects are typically categorized into mismatches between the sgRNA and DNA, RNA bulges (insertions), and DNA bulges (deletions). To mitigate off-target activity, AI-based prediction models are employed, primarily using two approaches. In the classification approach, genomic sites are labeled as “1” for off-target and “0” for on-target or non-off-target sites. In the regression approach, a continuous score is assigned to each site, representing the likelihood or severity of off-target activity. Reliable benchmark datasets are essential for training and evaluating these prediction models (Table 3).

Table 3. A summary of studies applying traditional machine learning and deep learning models/methods for off-target prediction in CRISPR/Cas9 editing.

Benchmark dataset and prediction algorithms