- 1State Key Laboratory of Seed Innovation, Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

- 2College of Agriculture, Yangtze University, Jingzhou, China

Thinopyrum species are native to coastal regions and have evolved notable salt tolerance mechanisms, including efficient Na+ exclusion and K+ retention, enhanced antioxidant capacity, and the accumulation of compatible solutes for osmoregulation. Among the Thinopyrum species, Th. ponticum has long been used as saline pasture and energy plant, which was recently suggested for the construction of a “Coastal Grass Belt” around the Bohai Sea. The salt tolerance in some Thinopyrum species, such as Th. ponticum, Th. elongatum, Th. bessarabicum, and Th. distichum have been transferred into wheat as (partial) amphiploid, addition, substitution, translocation, and introgression lines. The introgression lines with enhanced salt tolerance, derived from wheat × Th. ponticum had been utilized as salt-tolerant wheat varieties. In addition, amphiploids and perennial wheat have been developed as salt-tolerant forage crops. Salt tolerance in Thinopyrum species is governed by multiple genes, which have been mapped principally to homologous chromosomes group 3 and group 5. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses have revealed a number of differentially expressed genes (proteins) involved in the salt tolerance response in Thinopyrum species; however, few of these have been functionally characterized. Therefore, further work is needed to investigate gene networks underlying salt tolerance in Thinopyrum, which may serve as molecular targets for the genetic improvement of salt-tolerant forage crops such as Tritipyrum and staple crops like wheat.

1 Introduction

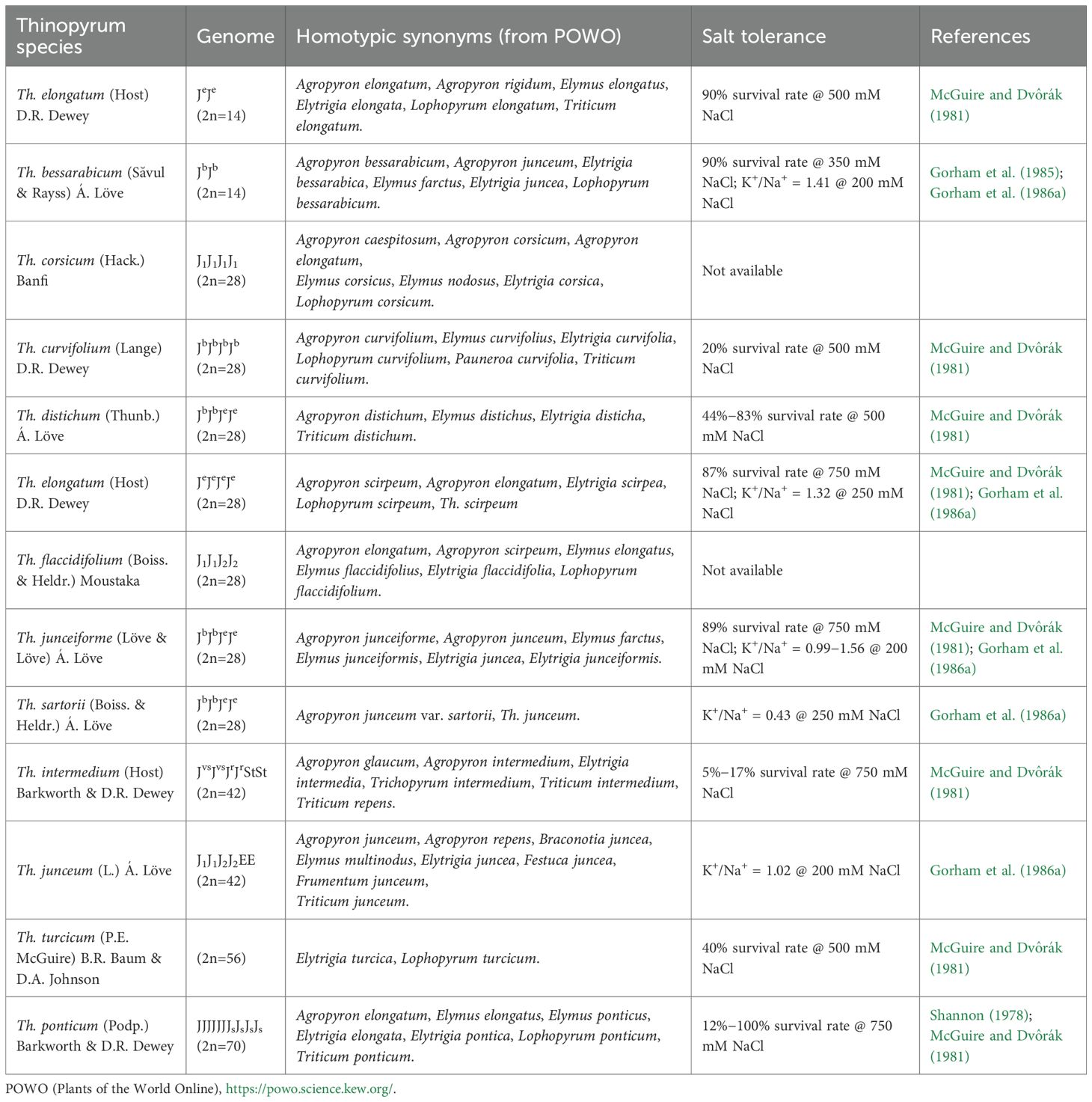

Genus Thinopyrum Á. Löve, erected in 1980 (Löve, 1980), consists of the species with E or J (= Eb) genome which have been classified as Triticum, Agropyron, Elymus, Elytrigia, and Lophopyrum previously. For sake of consistency with the existing literature, this paper uses Thinopyrum, notwithstanding the recent adoption of Lophopyrum by Yen and Yang (2022). Thinopyrum species include diploids (2n=14) Th. elongatum (Host) D.R. Dewey and Th. bessarabicum (Săvul. and Rayss) Á. Löve, tetraploids (2n=28) Th. corsicum (Hack.) Banfi, Th. curvifolium (Lange) D.R. Dewey, Th. distichum (Thunb.) Á. Löve, Th. flaccidifolium (Boiss. and Heldr.) Moustaka, Th. junceiforme (Á. Löve and D. Löve) Á. Löve, Th. sartorii (Boiss. and Heldr.) Á. Löve, and Th. elongatum (Host) D.R. Dewey, hexaploids (2n=42) Th. junceum (L.) Á. Löve and Th. intermedium (Host) Barkworth and D.R. Dewey, one octoploid (2n=56) Th. turcicum (P.E. McGuire) B.R. Baum, and one decaploid (2n=70) Th. ponticum (Podp.) Z.W. Liu and R.C. Wang. The detail information of Thinopyrum species is listed in Table 1. Most Thinopyrum species are maritime grasses native to the shores of the Baltic, Mediterranean, and North Sea, whereas Th. distichum originates from the coastal Cape Provinces of South Africa (Pienaar et al. 1988). As wild relatives of wheat, Thinopyrum species plays a pivotal role in wheat genetic improvement for resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses, including salinity (King et al., 1997a; Colmer et al., 2006; Urbanavičiūtė et al., 2021; Korostyleva et al., 2023; Tounsi et al., 2024).

Salt-affected soils cover approximately 932 million hectares (ha) of land worldwide, accounting for more than 10% of cropland (Rengasamy, 2006). This situation is further aggravated with faulty irrigation practices (Mohanavelu et al., 2021). Soil salinity is generally expressed as ECe (the electrical conductivity of saturated paste extract), EC1:5 (the electrical conductivity of soil:water = 1:5), the percentage of total soluble salts relative to soil (w/w), and exchangeable sodium percentag (ESP). Na+ exclusion is considered a major mechanism of salt tolerance in plants. Low Na+ accumulation and high K+/Na+ ratio in shoots are generally used as indices to discriminate salt-tolerant plants. To meet the ever-increasing food demand of the global human population, it is essential to extend the cultivation of food and forage crops in salt-affected soils. Salt stress usually inhibits photosynthesis, water and nutrient absorption, and plant growth, ultimately resulting in premature senescence and yield loss. Therefore, developing salt-tolerant varieties is a priority to maximize crop productivity and adaptability in saline-alkaline soils. Thinopyrum species have acquired high levels of salt tolerance from the coastal saline-alkaline environments. The transfer of salt tolerance from Thinopyrum into wheat has been thoroughly reviewed (King et al., 1997a; Colmer et al., 2006; Urbanavičiūtė et al., 2021; Kotula et al., 2024). This paper summarized recent approaches for investigating salt tolerance, salt-responsive genes, and pathways in Thinopyrum species.

2 Salt tolerance across Thinopyrum species

2.1 Salt tolerance in Th. ponticum

Th. ponticum, commonly known as tall wheatgrass, has long been cultivated as saline pasture and energy plant as well as for soil reclamation (Andrioli, 2023). Up till now, more than ten Th. ponticum cultivars have been released since the 1950s (Li et al., 2022a, b). A number of documents demonstrated that Th. ponticum is among the most salt-tolerant forage crops (Pearson and Bernstein, 1958; Dewey, 1960; Greenway and Rogers, 1963; Rogers and Bailey, 1963; Mcguire and Dvôrák, 1981; Roundy, 1983; Johnson, 1991; Pearen et al., 1997; Shen et al., 1999; Peng et al., 2002; Shen et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2006; Huang and Liang, 2007; Suyama et al., 2007a, 2007; Meng et al., 2009; Sepehry et al., 2012; Temel et al., 2015; Riedell, 2016; Borrajo et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022a; Xiao et al., 2025). For instance, several accessions of Th. ponticum showed high survival rates in the stepwise-increased final concentration of 750 mM NaCl (Shannon, 1978; McGuire and Dvôrák, 1981) and maintained reasonable growth in saline soil with ECe = 13.9 dS m–1 (Dewey, 1960). The 50% inhibition of germination and seedling emergence rates of two varieties, Tyrrell and Dundas, occurred at 300 and 110 mM NaCl, respectively (Zhang et al., 2005). Th. ponticum grew well and produced 6820, 5230, and 2920 kg ha–1 dry matter yield in high saline (ECe = 9.80 dS m–1, pH = 8.5, ESP = 11.9), high alkali (ECe = 0.89 dS m–1, pH = 10.3, ESP = 60.5), and high saline-alkali soils (ECe = 9.08 dS m–1, pH = 9.4, ESP = 49.7), respectively (Temel et al., 2015). However, according to 50% inhibition of shoot biomass, the salt tolerance of Th. ponticum was sometimes lower than that of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) (Sagers et al., 2017). Additionally, it has a low survival rate and does not grow well in very high-saline soils (ECe > 100 dS m–1) (Semple et al., 2008). Under saline/waterlogged conditions, puccinellia (Puccinellia ciliata Bor. cv. Menemen) grows better than Th. ponticum (Jenkins et al., 2010). A surface soil salinity of less than 1% (w/w) is recommended for the cultivation of Th. ponticum in coastal saline land, allowing for a high survival rate (Asay and Jensen, 1996; Li et al., 2023a). Once irrigation with saline water having ECw ≤ 5.42 dS m−1 and SAR ≤ 36.31 in late spring was recently suggested for tall wheatgrass production in the “Coastal Grass Belt” targeted area (Li et al., 2023c), which resulted in minimal risk of soil salinization after rainfall leaching in summer.

The salt tolerance in Th. ponticum has been transferred into wheat as partial amphiploids and translocation/introgression lines. For instance, the BC1 and BC2 offspring from Triticum aestivum × Th. ponticum can survive and set seeds under 350 mM NaCl stress for 30 days (Dvořák et al., 1985). The CS-Th. ponticum amphiploid, which has 54 chromosomes plus a pair of telosomes, accumulated less Na+ in the shoots than CS when exposed to 275 mM NaCl (Schachtman et al., 1989). A few salt-tolerant wheat introgression lines were established through somatic hybridization between T. aestivum cv. Jinan 177 and Th. ponticum (Wang et al., 2004), among which Shanrong 3 produced 22.6% higher grain yield than Dekang 961, a local salt-tolerant wheat cultivar, in soils with a salinity level of 0.3%−0.5% (Shan et al., 2006). Additionally, the salt tolerance of Shanrong 3 was manifested by high rates of both seed germination and seedling survival under 340 mM NaCl stress (Liu et al., 2012). Another introgression line, Shanrong 4, exhibited enhanced alkalinity tolerance under 100 mM mixed salt stress (NaHCO3: Na2CO3 = 9: 1, pH = 8.9) (Meng et al., 2017). In addition, a wheat-Th. ponticum translocation line, S148, was able to germinate in 400 mM NaCl solution (Yuan and Tomita, 2015). Recently, the durum wheat-Th. ponticum 7AL•7el1L recombinant lines with enhanced salt tolerance were developed (Tounsi et al., 2024).

2.2 Salt tolerance in the diploids Th. elongatum and Th. bessarabicum

Th. elongatum can survive under gradually increased 500 mM NaCl but cannot grow in 750 mM NaCl (McGuire and Dvôrák, 1981). An amphiploid from T. aestivum cv. Chinese Spring (CS) × Th. elongatum, which has complete Th. elongatum genome, exhibited a higher survival rate and produced more dry matter and seed yields than CS when exposed to 250 mM NaCl, 250 mM KCl, 75 mM MgSO4, 150 mM K2SO4, and 18.0 or 36.0 g L–1 of marine salt stress in hydroponic tanks (Dvořák and Ross, 1986) and in saline soil (Omielan et al., 1991). Under 200 mM NaCl stress, the CS-Th. elongatum amphiploid transports less Na+ into the shoots than CS (Schachtman et al., 1989). Another CS-Th. elongatum amphiploid line, Y1805, may synthesize more proline and soluble sugars and have higher activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase than CS under salt stress (Peng et al., 2022). The durum wheat-Th. elongatum 7EL recombinant lines greatly mitigated the effects of salt stress on root and leaf growth and enhanced the accumulation of photosynthetic pigments, compatible solutes, and antioxidant like ascorbate (Tounsi et al., 2024). Th. bessarabicum can withstand prolonged exposure to 350 mM NaCl in hydroponic culture and was considered an osmoconformer (Gorham et al., 1985). The CS-Th. bessarabicum amphiploid showed a higher survival rate and grain yield than CS in 250 mM NaCl (Gorham et al., 1986b; Forster et al., 1987; King et al., 1997b). Several Tritipyrum lines with enhanced salt tolerance and seed productivity have been developed from the offspring of tetraploid wheat T. durum × Th. bessarabicum (King et al., 1997b), which have the potential to be used as a new type of forage crop. In addition, perennial wheat derived from Thinopyrum also provides a great opportunity for both food and forage crops with enhanced salt tolerance (Cui et al., 2018).

2.3 Salt tolerance in other Thinopyrum species

The salt tolerance also exists in other polyploid Thinopyrum species (McGuire and Dvôrák, 1981; Rozema et al., 1983; Gorham et al., 1986a). For instance, both Th. junceiforme and Th. scirpeum can survive in stepwise-increased concentrations of 750 mM NaCl. Th. distichum showed a survival rate of 44%−83% in 500 mM NaCl, which is lower than that of Th. elongatum (McGuire and Dvôrák, 1981). One octoploid, Th. turcicum, previously described as Elyt. turcica (McGuire, 1983) and recently recognized as a distinct Thinopyrum species (Baum and Johnson, 2017), had a survival rate of 40% under 500 mM NaCl stress (McGuire and Dvôrák, 1981). The ratios of K+/Na+ increased according to Th. sartorii (0.43), Th. junceum (1.02), Th. scirpeum (1.32), and Th. bessarabicum (1.41) when cultured in 250 mM NaCl (Gorham et al., 1986a). The ratios of K+/Na+ in four accessions of Th. junceiforme ranged between 0.99 and 1.56 under 250 mM NaCl stress, indicating that genetic variation in salt tolerance exists among the Th. junceiforme genotypes (Gorham et al., 1986a). Th. junceiforme, commonly known as sea wheatgrass, is a segmental allotetraploid species (Genome J1J1J2J2, Dewey, 1984). Recently, a T. turgidum (emmer wheat)-sea wheatgrass amphiploid line, 13G819, germinated better than the emmer wheat parent under 200 mM NaCl stress (Li et al., 2019).

The CS-Th. elongatum amphiploid produced more yield and had a higher ratio of K+/Na+ than CS, the CS-Th. bessarabicum amphiploid, and the CS-Th. scirpeum amphiploid under 100−150 mM NaCl stress (Akhtar et al., 1994). The CS-Th. elongatum amphiploid was more tolerant and transported less Na+ from roots to shoots than the CS-Th. scirpeum amphiploid under 200 mM NaCl stress (Gorham, 1994). The salt tolerance of the durum wheat-Th. bessarabicum amphiploids was stronger than that of the durum wheat-Th. distichum amphiploids (Marais et al., 2014). Notably, Th. ponticum (acc. PI 276399) grew faster and had stronger selectivity for K+ over Na+ than the tetraploid Elyt. elongata (acc. PI 578686) in the presence of 100–200 mM NaCl (Guo et al., 2015). Furthermore, salt tolerance increased according to AgCS (CS×Th. elongatum-unkn.acc., genome ABDE), CSLt (CS×Th. turcicum, genome ABDEEEE), and LDNLp (durum wheat-LDN×Th. ponticum, genome ABEEEEE), indicating that the salt tolerance of the amphipods is dependent on the number of Thinopyrum chromosomes (Abbasi et al., 2020). Therefore, salt-tolerant crops may be developed through pyramiding more salt-tolerance genes (loci) distributing on different Thinopyrum chromosomes.

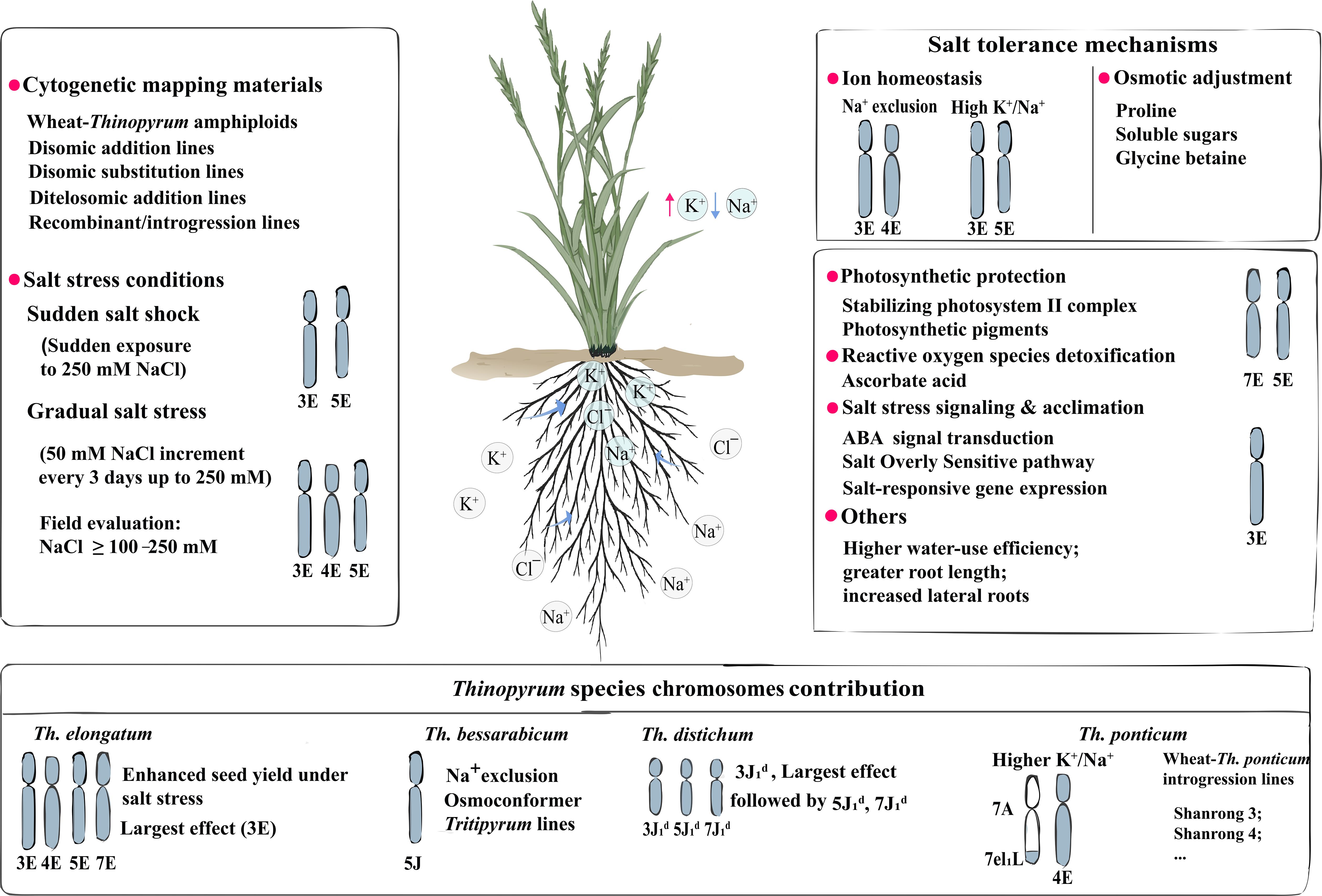

3 Chromosomes (segments) regulating salt tolerance in Thinopyrum species

The salt tolerance in Thinopyrum is controlled by multiple genes which have been mapped on different chromosomes by using the wheat-Thinopyrum disomic addition and substitution lines. For instance, Dvořák et al. (1988) mapped salt tolerance of Th. elongatum on chromosomes 3E, 4E, and 7E. A field evaluation showed that all seven chromosomes except 6E of Th. elongatum enhanced salt tolerance in the CS substitution lines, and 3E had the largest effect (Omielan et al., 1991). Both 3E and 4E were confirmed to maintain high ratios of K+/Na+ in the presence of 200 mM NaCl (Gorham, 1994).

Due to the diversity of genetic background of the plant material and the inconsistent conditions of different experimental setups, the identified chromosomes associated with salt tolerance are not always repeatable. Evidence suggests that tolerance to salt shock and gradual salt stress is regulated by different chromosomes. Salt shock tolerance, induced by a sudden exposure to 250 mM NaCl, is primarily governed by chromosomes 3E and 5E, whereas gradual salt stress tolerance, induced by 50 mM NaCl increments every three days up to 250 mM, is predominantly regulated by 3E, 4E, and 5E. However, the ditelosomic analysis further revealed that salt shock tolerance is associated with 1EL, 5ES, 5EL, 6EL, 7ES, and 7EL, while gradual salt stress tolerance is linked with 1ES, 1EL, 5ES, 5EL, 6ES, 7ES, and 7EL (Zhong and Dvořák, 1995). Chromosome 5E enhances tolerance to 250 mM NaCl by stabilizing the photosystem II complex and cytochrome pathway (Kasai et al., 1998). The K+/Na+ ratios in Th. elongatum subjected to 100 and 250 mM NaCl stress were mapped to 1ES, 7ES, and 7EL (Deal et al., 1999). Acclimation to salt stress in Th. elongatum is mainly governed by chromosome 3E, which is regulated by abscisic acid (ABA) and is accompanied by elevated expression of salt-responsive genes (Noaman et al., 2002). A recombinant line, 524-568, incorporating the smallest Th. elongatum 3EL chromatin segment onto the distal end of wheat chromosome 3AL, was shown to be responsible for Na+ exclusion under salt stress (Mullan et al., 2009). Moreover, chromosome 5J (=5Eb) of Th. bessarabicum harbors a major gene(s) for salt tolerance, characterized by Na+ exclusion from the leaves and roots (Forster et al., 1988; King et al., 1996; Mahmood and Quarrie, 1993).

Th. distichum possesses a genome constitution of J1dJ1dJ2dJ2d. From the cross between the Th. distichum-Secale cereal (2n=4x=28) amphiploid and diploid rye, fifteen F1 plants with high levels of salt tolerance were identified (Marais and Marais, 2003). Chromosomes 2J1d, 3J1d, 4J1d, 5J1d, and 7J1d were shown to be associated with salt tolerance in Th. distichum (Marais and Marais, 2003), with chromosome 3J1d exerting the strongest effect, followed by 5J1d and 7J1d (Botes and Marais, 2007). The introduction of chromosomes 2J1d and 3J1d into triticale appears to be the only combination that significantly enhances survival rate under salt stress. Furthermore, the addition of 2J1d, 3J1d, and 5J1d or of 3J1d, 4J1d, and 5J1d resulted in salt tolerance comparable to that of the primary Th. distichum-triticale amphiploid (Marais et al., 2007).

The wheat-Th. ponticum 4E(4D) substitution line exhibited a higher K+/Na+ ratio than common wheat under 150 mM NaCl stress (Xu et al., 1998). In the salt-tolerant cultivar Shanrong 3, salt tolerance has been associated with the SSR marker Xgwm 304 on wheat chromosome 5A (Shan et al., 2006). The wheat addition line AJDAj5 displayed salt tolerance comparable to that of wheat-Th. junceum partial amphiploids, and several salt-tolerant recombinant lines were subsequently developed from AJDAj5 (Wang et al., 2003). More recently, Zeng et al. (2023) developed a novel 3E(3D) substitution line derived from wheat × tetraploid Th. elongatum, which exhibited a lower Na+ concentration and higher K+/Na+ ratio in both shoots and roots under salinity stress compared with its wheat parents. This line also demonstrated a higher photosynthesis rate, improved water-use efficiency, greater antioxidant capacity, and enhanced osmotic adjustment under salt stress. Collectively, chromosomes from homologous groups 3 and 5 appear to play a key role in the regulation of salt tolerance in Thinopyrum species. Further research is required to delimit salt tolerance genes to small genome intervals to facilitate their utilization in cereal and forage crop improvement.

4 Salt-responsive genes in Thinopyrum species

Salt tolerance in Th. elongatum is closely correlated with the expression levels of the salt-responsive genes. A few early salt-induced (ESI) genes were markedly induced in roots of Th. elongatum within 2 h and peaked after 6 h exposure to 250 mM NaCl (Gulick and Dvořák, 1992; Galvez et al., 1993). Eleven ESIs were mapped on Th. elongatum chromosomes, of which ESI4, ESI14, ESI15, ESI28, and ESI32 were located in homoeologous group 5, ESI18 and ESI35 in group 6, and ESI47, ESI48, ESI3, and ESI2 in groups 1, 3, 4, and 7, respectively (Dubcovsky et al., 1994). The Salt Overly Sensitive (SOS) pathway plays a central role in plant salinity tolerance through modulation of the SOS core proteins at the transcriptional and post-translational levels (Ali et al., 2023). Among the Arabidopsis-rice-wheat gene orthologues for Na+ transport genes, SOS1 were mapped on 1EL and 3ES, NHX5 on 5EL, AVP2 on 6ES, AVP1 on 7ES, and HKT1 on 7EL, respectively (Mullan et al., 2007). The salt-responsive genes expressed differentially between the salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive Th. ponticum ecotypes under salt stress. For instance, the salt-tolerant lines showed higher expression of HKT1;4 and NAC9 in the leaves and roots than the salt sensitive lines (Sheikh-Mohamadi et al., 2022). In addition, the expression levels of NHX7.1/SOS1 and NCL1 were higher in the salt-tolerant Th. ponticum lines than in the salt-sensitive lines (Xiao et al., 2025).

Transcriptomic analysis can reveal more salt-response genes and discover novel mechanisms of salt tolerance in halophytes (Meng et al., 2018; Fan, 2020; Feng et al., 2025). In Th. ponticum exposed to 150 mM NaHCO3, 1833 and 1536 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in leaves and roots, respectively. Functional enrichment highlighted pathways involved in antioxidant biosynthesis, ion binding, and phenylalanine/phenylpropanoid metabolism. Enriched ion binding categories featured BAK1, CIPK10, STRK1, WAK8, and multiple laccase genes (Zhang et al., 2025a). Under 150 mM Na2SO4, 1682 leaf DEGs and 2816 root DEGs were identified, primarily associated with redox homeostasis, ion homeostasis, and signal transduction. Collectively, Th. ponticum appears to coordinate NAC/MYB/WRKY transcription factors, salicylic acid and ethylene signaling, and Ca2+-dependent pathways to cope with salt stress. Nine candidate genes, including UGT7472, JMT, T4E14.7, CAX5, CP1, PXG2, NAMT1, BON3, and APX7, have been proposed to contribute to salt stress in Th. ponticum (Zhang et al., 2025b).

Transcriptomic investigations of wheat-Thinopyrum materials have largely focused on amphiploids, substitution lines, and introgression lines. Across comparisons among the common wheat cultivar ‘Chinese Spring’ (CS), CS-Th. elongatum amphiploid, and the 3E(3A) substitution line, 304 DEGs were detected, 18 of which are involved in signal transduction or regulatory function. These include transcription factors, protein kinases, ubiquitin ligases, and genes participating in phospholipid signaling (Hussein et al., 2014). In the CS-Th. elongatum amphiploid Y1805, transcriptional regulatory networks respond both to salt stress and the subsequent recovery phase. Salt-responsive DEGs are enriched for peroxisomal processes, arginine and proline metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism, chlorophyll and porphyrin metabolism, and photosynthesis (Peng et al., 2022). Furthermore, assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) profiling of Y1805 identified 85 motifs within 1776 location-specific peaks and 478 motifs within peaks with altered accessibility under salt stress. Motif-associated transcription factors are dominated by the MYB family, followed by AP2/EREBP, bZIP, bHLH, and WRKY families. Gene Ontology (GO) analyses integrating ATAC-seq accessibility and RNA-seq expression indicate significant enrichment of organic and carboxylic acid catabolic process, cellular hormone and cytokinin metabolic, and cellular amino acid catabolism in Y1805 (Tian et al., 2024). These findings from wheat-Thinopyrum backgrounds provide a comparative framework for interpreting salt-response mechanisms in Th. ponticum.

Transcriptomic analyses of the CS-Th. elongatum amphiploid Y1805 indicates that several Th. elongatum salt-responsive genes, including TtLEA2-1 (Tel3E01G270600; Yang et al., 2022), TtWRKY256 (Tel1E01T143800; Li et al., 2022), TtERF_B2-50 (Tel2E01T236300; Liu et al., 2023), TtNAC477 (Tel3E01T644900; Liu et al., 2024), TtMYB1 (Tel2E01G633100; Mu et al., 2024), and TtbHLH310 (Tel1E01T336100; Li et al., 2025), show high expression across roots, stems, and leaves under salt stress. Functionally, overexpression of TtMYB1 (Mu et al., 2024) and TtHSF6-1 (Tel7E01G472900; Tian et al., 2024) enhanced salt tolerance in wheat, supporting their utility for genetic improvement. A root-specific vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter gene, AeNHX1, was isolated from Th. elongatum, its overexpression conferred increased salt tolerance in Arabidopsis and Festuca species (Qiao et al., 2007). Consistent with the role of ion transport, exclusion of Na+ from leaves and vacuolar or cell-type-specific compartmentation depend on changes in ion transporters expression (Munns and Tester, 2008). From Th. ponticum, a salt-induced high-affinity potassium transporter, EeHKT1;4, was cloned (Zhang et al., 2022b); its overexpression in Arabidopsis improved tolerance to salt and drought and reduced reactive oxygen species under stress (Zhang et al., 2022b).

Beyond Thinopyrum, transcriptome-guided analyses identified a putative potassium channel gene implicated in tissue-level salt tolerance in wheat recombinant lines W4909 and W4910 derived from AJDAj5 × PhI (bearing the PhI allele from Aegilops speltoides) (Mott and Richard, 2007). Comparative profiling further showed higher expression of genes involved in stress response, unsaturated-fatty-acid and flavonoid biosynthesis, and the pentose-phosphate pathway in Shanrong 3 versus Jinan 177 (Liu et al., 2012). Under alkaline stress, 5691 and 5932 long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) were identified in Shanrong 4 and Jinan 177, respectively (Wei et al., 2022), suggesting that differential lncRNAs-mediated regulation of alkaline tolerance between these genotypes.

5 Differentially expressed proteins responding to salt in Thinopyrum species

Proteomic studies indicate that a broad set of mitochondrial proteins responds to salinity in CS and CS-Th. elongatum amphiploid, notably enzymes involved in detoxifying reactive oxygen species (ROS), including manganese superoxide dismutase, serine hydroxymethyltransferase, aconitase, malate dehydrogenase, and β-cyanoalanine synthase (Jacoby et al., 2013). In total, 44 and 102 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were identified in Y1805 under salt stress and recovery process, respectively (Yang et al., 2021), among which eight DEPs were specifically responsive to salt stress. Relative to CS, pathways in Y1805 were characterized by energy and lipid metabolism during recovery, whereas antioxidant activity and molecular function regulator activity were prominent under salt stress; during recovery, the GO terms “virion” and “virion part” were also recorded. In seedling roots, 114 DEPs distinguished Shanrong 3 from Jinan 177 under salt stress, spanning signal transduction, transcription/translation, transport, chaperones, proteolysis, and detoxification etc (Wang et al., 2008). Across leaves and roots, 93 and 65 DEPs were detected under drought and salt stress, respectively (Peng et al., 2009). Shanrong 3’s salt tolerance has been linked to more efficient removal of toxic by-products, supported by stronger osmotic and ionic homeostasis and better post-stress regrowth (Peng et al., 2009).

6 Mechanism of salt tolerance in Thinopyrum species

The mechanisms of salt-alkali tolerance in Th. ponticum have been reviewed (Andrioli, 2023), and primarily encompasses Na+ exclusion, high K+/Na+selectivity, and osmotic adjustment (osmoprotection). Forage productivity of Th. ponticum correlates with leaf Na+ exclusion and the K+/Na+ ratio under saline conditions (Johnson, 1991). Salinity tolerance has also been associated with Na+ and Cl− concentrations in fodder (Bhuiyan et al., 2017) and with greater uptake and selective transport of K+ over Na+ (Guo et al., 2015). Additional contributing traits include elevated proline and soluble sugars (Shannon, 1978); high water-use efficiency with relatively invariant 13C discrimination (Johnson, 1991); and maintenance of shoot osmolality via regulation of Na+ and K+ contents, while mitigating Ca2+ deficiency during salt stress (Zhang et al., 2005).

Similarly, increased salt tolerance of wheat-Thinopyrum amphiploid correlates with Na+ and Cl− exclusion, K+ retention, and K+ retranslocation within shoots (Gorham et al., 1986b; Omielan et al., 1991; Schachtman et al., 1989; Santa-María and Epstein, 2001). In the CS-Th. elongatum amphiploid, low Na+, high K+, and accumulation of glycine betaine in young leaves were associated with enhanced salt tolerance (Colmer et al., 1995). By contrast, the CS-Th. bessarabicum amphidiploid did not inherit the high glycine betaine concentrations characteristic of Th. bessarabicum (Gorham et al., 1986b). In Y1805, salt tolerance has been linked to strengthened cell walls, reactive oxygen species scavenging, osmoregulation, phytohormone regulation, transient growth arrest, enhanced respiration, transcriptional regulation, and error information processing (Yang et al., 2021). The wheat-Th. ponticum introgression line Shanrong 3 exhibits higher selectivity for K+ over Na+, thereby limiting Na+ transport from root to shoot (Shan et al., 2008).

Although Th. ponticum is widely regarded as highly salt-tolerant, intraspecific variation and its mechanisms remain underexplored (McGuire and Dvoák, 1981; Shannon, 1978; Borrajo et al., 2021, 2022). Phenotyping indicates that salt-tolerant ecotypes exhibit greater initial root length and lateral root density, together with lower accumulation of reactive oxygen species and malondialdehyde (MDA), than the salt-sensitive ecotypes (Sheikh-Mohamadi et al., 2022). High-resolution omics, including single-cell RNA sequencing, and spatial transcriptomics help discover novel mechanisms of salt tolerance in Thinopyrum species. The mechanisms and chromosomes (segments) regulating salt tolerance in Thinopyrum species were summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mechanisms and chromosomes (segments) regulating salt tolerance in Thinopyrum species. The upper two boxes were principally summarized from Th. elongatum.

7 Prospect for exploiting salt tolerance in Thinopyrum species for forage and food production

Although Th. ponticum has substantial potential as a saline pasture, a bioenergy crop, and for soil reclamation on marginal lands including saline-alkaline soils (Falasca et al., 2017; Csete et al., 2011; Ciria et al., 2020; Scordia et al., 2022), it remains underutilized due to poor management and limited attention (Smith, 1996). In China, it has long served as a wild donor for distant hybridization in wheat, but has been used less as a forage crop since its introduction in the 1950s. Recently, a “Coastal Grass Belt” has been proposed for coastal saline-alkaline soils around the Bohai Sea that are unprofitable for food crops. Such a belt would help meet the growing demand for high-quality forage while minimizing competition with food crops for arable land (Xu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023b). The deployment of Th. ponticum varieties that combine enhanced salt and alkali tolerance with high productivity will largely determine the scale of utilization. A comprehensive and standardized evaluation of salt tolerance across Thinopyrum species is needed. Molecular breeding strategies, including development of polymorphic molecular markers, construction of high-density linkage maps, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), pyramiding of salt tolerance genes, and genome editing, will accelerate the breeding of Th. ponticum varieties. The growing genome sequences of Thinopyrum species enable researches to map and isolate salt tolerance genes in Thinopyrum species. For instance, Wang et al. (2020a) reported for the first time the genome sequence of Th. elongatum (acc. D-3458) which has a 4.63 Gb assembly. In addition, two genome sequences of Th intermedium v2.1 with 10.92 Gb of assembled sequence (Thinopyrum intermedium v2.1 DOE-JGI) (Thinopyrum intermedium v2.1 DOE-JGI), and Th. intermedium (acc. PI 440031) with 10.89 Gb of assembled sequence (Sun et al., 2025) were also available. F1 progeny from wheat × Th. ponticum crosses retain the perennial habit of Th. ponticum and can grow faster and produce more forage than Th. ponticum itself (Wang et al., 2020b), suggesting a new avenue for forage production if clonal seed production can be enabled through genome editing. In addition, salt-tolerant forage crops such as Tritipyrum and perennial wheat may be developed from crosses between wheat or rye and Thinopyrum species (Hassani et al., 2000). Several salt-tolerant Tritipyrum lines with high straw and grain yields have been reported (Kamyab et al., 2012, 2017, 2018). Salt-tolerant wheat introgression lines carrying small Thinopyrum chromosome segments without evident linkage drag, such as Shanrong 3 and Shanrong 4, can be deployed directly as wheat cultivars. Furthermore, salt-tolerance genes isolated from Thinopyrum species may serve as molecular targets for improving other crops, including wheat.

8 Conclusions

Species in the genus Thinopyrum exhibit high levels of tolerance to salt and alkali stress, and this trait appears polygenic with largely additive effects. Progeny from wheat × Thinopyrum crosses with enhanced salt tolerance can be used as both forage and grain crops. Using chromosome addition and substitution lines, salt tolerance loci have been mapped to multiple chromosomes of Th. elongatum, Th. bessarabicum, Th. distichum, and Th. ponticum, with homologous group 3 and group 5 showing the largest effects. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses have identified many salt-responsive genes (proteins), yet only a small subset has undergone functional validation. Going forward, mechanisms of salt tolerance and the associated transcription regulatory networks should be resolved through comprehensive and standardized phenotyping across Thinopyrum germplasm together with genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and targeted functional studies.

Author contributions

WL: Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft. HL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. QZ: Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA26040105).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Fei He for his valuable suggestions, which significantly improved this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbasi, J., Dvořák, J., McGuire, P., and Dehghani, H. (2020). Perennial growth and salinity tolerance in wheat × wheatgrass amphiploids varying in the ratio of wheat to wheatgrass genomes. Plant Breed. 139, 1281–1289. doi: 10.1111/pbr.12856

Akhtar, J., Gorham, J., and Qureshi, R. H. (1994). Combined effect of salinity and hypoxia in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and wheat–Thinopyrum amphiploids. Plant Soil 166, 47–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02185480

Ali, A., Petrov, V., Yun, D. J., and Gechev, T. (2023). Revisiting plant salt tolerance: novel components of the SOS pathway. Trends Plant Sci. 28, 1060–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2023.04.003

Andrioli, R. J. (2023). Adaptive mechanisms of tall wheatgrass to salinity and alkalinity stress. Grass Forage Sci. 78, 23–36. doi: 10.1111/gfs.125856

Asay, K. H. and Jensen, K. B. (1996). “Wheatgrasses,” in Cool-season forage grasses. Eds. Moser, L. E., Buxton, D. R., and Casler, M. D. (ASA, CSSA, and SSSA, Madison, WI), 691–724.

Baum, B. and Johnson, D. A. (2017). Validation of Thinopyrum turcicum and T. varnense (Poaceae, Pooideae, Triticeae). Novon 25, 419–420. doi: 10.3417/2011005

Bhuiyan, M. S. I., Raman, A., Hodgkins, D., Mitchell, D., and Nicol, H. I. (2017). Influence of high levels of Na+ and Cl– on ion concentration, growth, and photosynthetic performance of three salt-tolerant plants. Flora 228, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2017.01.002

Borrajo, C. I., Sánchez-Moreiras, A. M., and Reigosa, M. J. (2021). Morpho-physiological, biochemical and isotopic response of tall wheatgrass populations to salt stress. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 207, 236–248. doi: 10.1111/jac.12461

Borrajo, C. I., Sánchez-Moreiras, A. M., and Reigosa, M. J. (2022). Ecophysiological responses of tall wheatgrass germplasm to drought and salinity. Plants 11, 1548. doi: 10.1111/jac.12461

Botes, W. C. and Marais, G. F. (2007). “Determining the salt tolerance of triticale disomic addition (Thinopyrum additions) lines”, in Wheat production in stressed environments. Developments in plant breeding, vol. 12 . Eds. Buck, H. T., Nisi, E., and Salomón, N. (Springer, Dordrecht).

Ciria, C. S., Sastre, C. M., Carrasco, J., and Ciria, P. (2020). Tall wheatgrass (Thinopyrum ponticum (Podp.)) in a real farm context, a sustainable perennial alternative to rye (Secale cereale L.) cultivation in marginal lands. Ind. Crops Prod. 146, 112184. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112184

Colmer, T. D., Epstein, E., and Dvořák, J. (1995). Differential solute regulation in leaf blades of various ages in salt-sensitive wheat and a salt-tolerant wheat × Lophopyrum elongatum (Host) A. Löve amphiploid. Plant Physiol. 108, 1715–1724. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.4.1715

Colmer, T. D., Flowers, T. J., and Munns, R. (2006). Use of wild relatives to improve salt tolerance in wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 1059–1078. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj124

Csete, S., Stranczinger, S., Szalontai, B., Farkas, Á., Pál, R., Salamon-Albert, É., et al. (2011). “Tall wheatgrass cultivar Szarvasi-1 (Elymus elongatus subsp. ponticus cv. Szarvasi-1) as a potential energy crop for semi-arid lands of Eastern Europe”, in Sustainable growth and applications in renewable energy sources. Ed. Nayeripou, M. (IntechOpen, London, UK), 269–294.

Cui, L., Ren, Y., Murray, T., Yan, W., Guo, Q., Niu, Y., et al. (2018). Development of perennial wheat through hybridization between wheat and wheatgrasses: a review. Engineering 4, 507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2018.07.001

Deal, K., Goyal, S., and Dvorak, J. (1999). Arm location of Lophopyrum elongatum genes affecting K+/Na+ selectivity under salt stress. Euphytica 108, 193–198. doi: 10.1023/A:1003685032674

Dewey, D. R. (1960). Salt tolerance of twenty-five strains of Agropyron. Agron. J. 52, 631–635. doi: 10.2134/agronj1960.00021962005200110006x

Dewey, D. R. (1984). “The genomic system of classification as a guide to intergeneric hybridization with the perennial Triticeae”, in Gene manipulation in plant improvement. Ed. Gustafson, J. P. (Plenum, New York), 209–279.

Dubcovsky, J., Galvez, A. F., and Dvořák, J. (1994). Comparison of the genetic organization of the early salt-stress-response gene system in salt-tolerant Lophopyrum elongatum and salt-sensitive wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 87, 957–964. doi: 10.1007/bf00225790

Dvořák, J., Edge, M., and Ross, K. (1988). On the evolution of the adaptation of Lophopyrum elongatum to growth in saline environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 3805–3809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.3805

Dvořák, J. and Ross, K. (1986). Expression of tolerance of Na+, K+, Mg2+, Cl– and SO42– ions and sea water in the amphiploid of Triticum aestivum × Elytrigia elongata. Crop Sci. 26, 658–660. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1986.0011183X002600040002x

Dvořák, J., Ross, K., and Mendlinger, S. (1985). Transfer of salt tolerance from Elytrigia pontica (Podp.) Holub to wheat by the addition of an incomplete Elytrigia genome. Crop Sci. 25, 306–309. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1985.0011183X002500020023x

Falasca, S. L., Miranda, C., and Alvarez, S. P. (2017). Agro-ecological zoning for tall wheatgrass (Thinopyrum ponticum) as a potential energy and forage crop in salt-affected and dry lands of Argentina. Arch. Crop Sci. 1, 10–19. doi: 10.36959/718/597

Fan, C. (2020). Genetic mechanisms of salt stress responses in halophytes. Plant Signal. Behav. 15, 1704528. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2019.1704528

Feng, H., Zhao, J., Xiao, F., Wang, S., Jiang, Y., Lu, Y., et al. (2025). Quantitative proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses reveal salt tolerance mechanisms of the halophyte Hordeum brevisubulatum. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 228, 110284. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.110284

Forster, B. P., Gorham, J., and Miller, T. E. (1987). Salt tolerance of an amphiploid between Triticum aestivum and Agropyron junceum. Plant Breed. 98, 1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.1987.tb01083.x

Forster, B. F., Miller, T. E., and Law, C. N. (1988). Salt tolerance of two wheat-Agropyron junceum disomic addition lines. Genome 30, 559–564. doi: 10.1139/g88-094

Galvez, A. F., Gulick, P. J., and Dvořák, J. (1993). Characterization of the early stages of genetic salt-stress responses in salt-tolerant Lophopyrum elongatum, salt-sensitive wheat, and their amphiploid. Plant Physiol. 103, 257–265. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.1.257

Gorham, J. (1994). Salt tolerance in the Triticeae: K/Na discrimination in some perennial wheatgrasses and their amphiploids with wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 45, 441–447. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23693906 (Accessed September 22, 2025).

Gorham, J., Budrewicz, E., McDonnell, E., and Jones, R. G. W. (1986a). Salt tolerance in the Triticeae: salinity-induced changes in the leaf solute composition of some perennial Triticeae. J. Exp. Bot. 37, 1114–1128. doi: 10.1093/jxb/37.8.1114

Gorham, J., Forster, B. P., Jones, R. G. W., Miller, T. E., and Law, C. N. (1986b). Salt tolerance in the Triticeae: solute accumulation and distribution in an amphidiploid derived from Triticum aestivum cv. Chinese Spring and Thinopyrum bessarabicum. J. Exp. Bot. 37, 1435–1449. doi: 10.1093/jxb/37.10.1435

Gorham, J., McDonnell, E., Budrewicz, E., and Jones, R. G. W. (1985). Salt tolerance in the Triticeae: growth and solute accumulation in leaves of Thinopyrum bessarabicum. J. Exp. Bot. 36, 1021–1031. doi: 10.1093/jxb/36.7.1021

Greenway, H. and Rogers, A. (1963). Growth and ion uptake of Agropyron elongatum on saline substrates, as compared with a salt-tolerant variety of Hordeum vulgare. Plant Soil 18, 21–30. doi: 10.1007/BF01391677

Gulick, P. J. and Dvořák, J. (1992). Coordinate gene response to salt stress in Lophopyrum elongatum. Plant Physiol. 100, 1384–1388. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.3.1384

Guo, Q., Meng, L., Mao, P., and Tian, X. (2015). Salt tolerance in two tall wheatgrass species is associated with selective capacity for K+ over Na+. Acta Physiol. Plant 37, 1708. doi: 10.1007/s11738-014-1708-4

Hassani, H. S., King, I. P., Reader, S. M., Caligari, P. D. S., and Miller, T. E. (2000). Can tritipyrum, a new salt tolerant potential amphiploid, be a successful cereal like triticale? JAST 2, 177–195.

Huang, L. H. and Liang, Z. W. (2007). Effect of different sodium salt stress on the seed germination of tall wheatgrass (Agropyron elongatum). J. Arid Land Res. Environ. 21, 173–176.

Huang, L. H., Liang, Z. W., Wang, Z. C., Yang, F., and Chen, Y. (2006). Effect of saline-sodic stress on seedling growth and content of K+ and Na+ of Agropyron elongatum. Chin. J. Grassl. 28, 60–65.

Hussein, Z., Dryanova, A., Maret, D., and Gulick, P. J. (2014). Gene expression analysis in the roots of salt-stressed wheat and the cytogenetic derivatives of wheat combined with the salt-tolerant wheatgrass, Lophopyrum elongatum. Plant Cell Rep. 3, 189–201. doi: 10.1007/s00299-013-1522-2

Jacoby, R. P., Millar, A. H., and Taylor, N. L. (2013). Investigating the role of respiration in plant salinity tolerance by analyzing mitochondrial proteomes from wheat and a salinity-tolerant amphiploid (wheat × Lophopyrum elongatum). J. Proteome Res. 12, 4807–4829. doi: 10.1021/pr400504a

Jenkins, S., Barrett-Lennard, E. G., and Rengel, Z. (2010). Impacts of waterlogging and salinity on Puccinellia (Puccinellia ciliata) and tall wheatgrass (Thinopyrum ponticum): zonation on saltland with a shallow water-table, plant growth, and Na+ and K+ concentrations in the leaves. Plant Soil 329, 91–104. doi: 10.1007/s11104-009-0137-4

Johnson, R. (1991). Salinity resistance, water relations, and salt content of crested and tall wheatgrass accessions. Crop Sci. 31, 730–734. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1991.0011183X003100030039x

Kamyab, M., Hassani, H. S., and Tohidinejad, E. (2012). Agronomic behavior of a new cereal (Primary 6× tritipyrum: AABBEbEb) in comparison with modern triticale and Iranian bread wheat cultivars. JAST-B 2, 38–51.

Kamyab, M., Kafi, M., Shahsavand, H., Goldani, M., and Shokouhifar, F. (2017). Biochemical mechanisms of salinity tolerance in new promising salt-tolerant cereal, tritipyrum (Triticum durum × Thinopyrum bessarabicum). Aust. J. Crop Sci. 11, 701–710. doi: 10.21475/ajcs.17.11.06.p434

Kamyab, M., Kafi, M., Shahsavand, H., Goldani, M., and Shokouhifar, F. (2018). Tritipyrum (Triticum durum × Thinopyrum bessarabicum) might be able to provide an economic and stable solution against the soil salinity problem. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 12, 1159–1168. doi: 10.21475/AJCS.18.12.07.PNE1127

Kasai, K., Fukayama, H., Uchida, N., Mori, N., Yasuda, T., Oji, Y., et al. (1998). Salinity tolerance in Triticum aestivum–Lophopyrum elongatum amphiploid and 5E disomic addition line evaluated by NaCl effects on photosynthesis and respiration. Cereal Res. Commun. 26, 281–287. doi: 10.1007/BF03543501

King, I. P., Forster, B. P., Law, C. N., Cant, K. A., Orford, S. E., Gorham, J., et al. (1997a). Introgression of salt-tolerance genes from Thinopyrum bessarabicum into wheat. New Phytol. 137, 75–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00828.x

King, I. P., Law, C. N., Cant, K. A., Orford, S. E., Reader, S. M., and Miller, T. E. (1997b). Tritipyrum, a potential new salt-tolerant cereal. Plant Breed. 116, 127–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.1997.tb02166.x

King, I. P., Orford, S. E., Cant, K. A., Reader, S. M., and Miller, T. E. (1996). An assessment of the salt tolerance of wheat/T. bessarabicum 5Eb addition and substitution lines. Plant Breed. 115, 77–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.1996.tb00876.x

Korostyleva, T. V., Shiyan, A. N., and Odintsova, T. I. (2023). The genetic resource of Thinopyrum elongatum (Host) D. R. Dewey in breeding improvement of wheat. Russ. J. Genet. 59, 983–990. doi: 10.31857/S0016675823100077

Kotula, L., Zahra, N., Farooq, M., Shabala, S., and Siddique, K. (2024). Making wheat salt tolerant: What is missing? Crop J. 12, 1299–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2024.01.005

Li, K., Cong, C., Wang, Y., Zhang, H., Li, Y., Xiao, J., et al. (2025). Genome-wide analysis of the tritipyrum bHLH gene family and the response of TtbHLH310 in salt tolerance. BMC Genomics 26, 549. doi: 10.1186/s12864-025-11657-z

Li, H., Li, W., Zheng, Q., Zhao, M., Wang, J., Li, B., et al. (2023a). Salinity threshold of tall wheatgrass for cultivation in coastal saline and alkaline land. Agriculture 13, 337. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13020337

Li, K., Liu, X., He, F., Chen, S., Zhou, G., Wang, Y., et al. (2022b). Genome-wide analysis of the tritipyrum WRKY gene family and the response of TtWRKY256 in salt-tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1042078

Li, W., Yin, J., Ma, D., Zheng, Q., Li, H., Wang, J., et al. (2023c) Acceptable salinity level for saline water irrigation of tall wheatgrass in edaphoclimatic scenarios of the coastal saline-alkaline land around Bohai Sea. Agriculture 13, 2117. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13112117

Li, W., Zhang, Q., Wang, S., Langham, M. A., Singh, D., Bowden, R. L., et al. (2019). Development and characterization of wheat-sea wheatgrass (Thinopyrum junceiforme) amphiploids for biotic stress resistance and abiotic stress tolerance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 132, 163–175. doi: 10.1007/s00122-018-3205-4

Li, H., Zheng, Q., Li, B., and Li, Z. (2022a). Research progress on the aspects of molecular breeding of tall wheatgrass. Sci. Bull. 57, 792–801. doi: 10.11983/CBB22152

Li, H., Zheng, Q., Li, B., Zhao, M., and Li, Z. (2022b). Progress in research on tall wheatgrass as a salt-alkali tolerant forage grass. Acta Pratacult Sin. 31, 190–199. doi: 10.11686/cyxb2021384

Li, H., Zheng, Q., Wang, J., Sun, H., Zhang, K., Fang, H., et al. (2023b). Industrialization of tall wheatgrass for construction of “Coastal Grass Belt”. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 38, 622–631. doi: 10.16418/j.issn.1000-3045.20230206001

Liu, C., Li, S., Wang, M., and Xia, G. (2012). A transcriptomic analysis reveals the nature of salinity tolerance of a wheat introgression line. Plant Mol. Biol. 78, 159–169. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9854-1

Liu, X., Zhou, G., Chen, S., Jia, Z., Zhang, S., He, F., et al. (2024). Genome-wide analysis of the tritipyrum NAC gene family and the response of TtNAC477 in salt tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 24, 40. doi: 10.1186/s12870-023-04629-6

Liu, X., Zhou, G., Chen, S., Jia, Z., Zhang, S., Ren, M., et al. (2023). Genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF gene family in tritipyrum and the response of TtERF_B2–50 in salt-tolerance. BMC Genomics 24, 541. doi: 10.1186/s12864-023-09585-x

Mahmood, A. and Quarrie, S. A. (1993). Effects of salinity on growth, ionic relations and physiological traits of wheat, disomic addition lines from Thinopyrum bessarabicum, and two amphiploids. Plant Breed. 110, 265–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.1993.tb00589.x

Marais, G. F., Ghai, M., Marais, A. S., Loubser, D., and Eksteen, A. (2007). Molecular tagging and confirmation of Thinopyrum distichum chromosomes that contribute to its salt tolerance. Can. J. Pure Appl. Sci. 1, 1–8.

Marais, G. F. and Marais, A. S. (2003). Identification of Thinopyrum distichum chromosomes responsible for its salt tolerance. S. Afr J. Plant Soil 20, 103–110. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/AJA02571862_910 (Accessed September 22, 2025).

Marais, F., Simsek, S., Poudel, R. S., Cookman, D., and Somo, M. (2014). Development of hexaploid (AABBJJ) tritipyrums with rearranged Thinopyrum distichum (Thunb.) Á. Löve-derived genomes. Crop Sci. 54, 2619–2630. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2014.02.0106

McGuire, P. E. (1983). Elytrigia turcica sp. nova, an octoploid species of the E. elongata complex. Folia Geobot Phytotax 18, 107–109. doi: 10.1007/BF02855642

McGuire, P. E. and Dvořák, J. (1981). High salt tolerance potential in wheatgrasses. Crop Sci. 21, 702–705. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1981.0011183X002100050018x

Meng, C., Quan, T. Y., Li, Z. Y., Cui, K. L., Yan, L., Liang, Y., et al. (2017). Transcriptome profiling reveals the genetic basis of alkalinity tolerance in wheat. BMC Genomics 18, 24. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3421-8

Meng, L., Shang, C. Y., Mao, P. C., Zhang, G. F., and An, S. Z. (2009). A comprehensive evaluation of salt tolerance for germplasm and materials of Elytrigia at the seedling stage. Acta Pratacult Sin. 18, 67–74.

Meng, X., Zhou, J., and Sui, N. (2018). Mechanisms of salt tolerance in halophytes: current understanding and recent advances. Open Life Sci. 13, 149–154. doi: 10.1515/biol-2018-0020

Mohanavelu, A., Naganna, S. R., and Al-Ansari, N. (2021). Irrigation-induced salinity and sodicity hazards on soil and groundwater: an overview of its causes, impacts and mitigation strategies. Agriculture 11, 983. doi: 10.3390/agriculture11100983

Mott, I. and Richard, W. (2007). Comparative transcriptome analysis of salt-tolerant wheat germplasm lines using wheat genome arrays. Plant Sci. 173, 327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.06.005

Mu, Y., Shi, L., Tian, H., Tian, H., Zhang, J., Zhao, F., et al. (2024). Characterization and transformation of TtMYB1 transcription factor from tritipyrum to improve salt tolerance in wheat. BMC Genomics 25, 163. doi: 10.1186/s12864-024-10051-5

Mullan, D. J., Colmer, T. D., and Francki, M. G. (2007). Arabidopsis–rice–wheat gene orthologues for Na+ transport and transcript analysis in wheat-L. elongatum aneuploids under salt stress. Mol. Genet. Genomics 277, 199–212. doi: 10.1007/s00438-006-0184-y

Mullan, D. J., Mirzaghaderi, G., Walker, E., Colmer, T. D., and Francki, M. G. (2009). Development of wheat-Lophopyrum elongatum recombinant lines for enhanced sodium ‘exclusion’ during salinity stress. Theor. Appl. Genet. 119, 1313–1323. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1136-9

Munns, R. and Tester, M. (2008). Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 651–681. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092911

Noaman, M. M., Dvořák, J., and Dong, J. M. (2002). “Genes inducing salt tolerance in wheat, Lophopyrum elongatum and amphiploid and their responses to ABA under salt stress”, in Prospects for saline agriculture. Tasks for vegetation science. Eds. Ahmad, R. and Malik, K. A. (Springer, Dordrecht), 37.

Omielan, J. A., Epstein, E., and Dvořák, J. (1991). Salt tolerance and ionic relations of wheat as affected by individual chromosomes of salt-tolerant Lophopyrum elongatum. Genome 34, 961–974. doi: 10.1139/g91-149

Pearen, J. R., Pahl, M. D., Wolynetz, M. S., and Hermesh, R. (1997). Association of salt tolerance at seedling emergence with adult plant performance in slender wheatgrass. Can. J. Plant Sci. 77, 81–89. doi: 10.4141/P95-159

Pearson, G. A. and Bernstein, L. (1958). Influence of exchangeable sodium on yield and chemical composition of plants: II. Wheat, barley, oats, rice, tall fescue, and tall wheatgrass. Soil Sci. 86, 254–261. doi: 10.1097/00010694-195811000-00005

Peng, Z., Wang, Y., Geng, G., Yang, R., Yang, Z., Yang, C., et al. (2022). Comparative analysis of physiological, enzymatic, and transcriptomic responses revealed mechanisms of salt tolerance and recovery in tritipyrum. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.800081

Peng, Z., Wang, M., Li, F., Lv, H., Li, C., and Xia, G. (2009). A proteomic study of the response to salinity and drought stress in an introgression strain of bread wheat. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 2676–2686. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900052-MCP200

Peng, Y. X., Zhang, L. J., Yu, Y. J., and Liu, G. (2002). Salt tolerance of seeds and seedlings of Elytrigia. Inner Mongolia Pratac 14, 42–43.

Pienaar, R. D. V., Littlejohn, G. M., and aSears, E. R. (1988). Genomic relationships in thinopyrum. S. Afr J. Bot. 54, 541–550. doi: 10.1016/S0254-6299(16)31251-0

Qiao, W. H., Zhao, X. Y., Li, W., Luo, Y., and Zhang, X. S. (2007). Overexpression of AeNHX1, a root-specific vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter from Agropyron elongatum, confers salt tolerance to Arabidopsis and Festuca plants. Plant Cell Rep. 26, 1663–1672. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0354-3

Rengasamy, P. (2006). World salinization with emphasis on Australia. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 1017–1023. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj108

Riedell, W. E. (2016). Growth and ion accumulation responses of four grass species to salinity. J. Plant Nutr. 39, 2115–2125. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2016.1193611

Rogers, A. L. and Bailey, E. T. (1963). Salt tolerance trials with forage plants in south Western Australia. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. Anim. Husb 3, 125–130. doi: 10.1071/EA9630125

Roundy, B. A. (1983). Response of basin wildrye and tall wheatgrass seedlings to salination. Agron. J. 75, 67–71. doi: 10.2134/agronj1983.00021962007500010017x

Rozema, J., Van Manen, Y., Vugts, H. F., and Leusink, A. (1983). Airborne and soilborne salinity and the distribution of coastal and inland species of the genus Elytrigia. Acta Bot. Neerl 32, 447–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.1983.tb01741.x

Sagers, J. K., Waldron, B. L., Creech, J. E., Mott, I. W., and Bugbee, B. (2017). Salinity tolerance of three competing rangeland plant species: studies in hydroponic culture. Ecol. Evol. 7, 10916–10929. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3607

Santa-María, G. E. and Epstein, E. (2001). Potassium/sodium selectivity in wheat and the amphiploid cross wheat × Lophopyrum elongatum. Plant Sci. 160, 523–534. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(00)00419-2

Schachtman, D. P., Bloom, A. J., and Dvořák, J. (1989). Salt-tolerant Triticum × Lophopyrum derivatives limit the accumulation of sodium and chloride ions under saline stress. Plant Cell Environ. 12, 47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1989.tb01915.x

Scordia, D., Papazoglou, E. G., Kotoula, D., Sanz, M., Ciria, C. S., Pérez, J., et al. (2022). Towards identifying industrial crop types and associated agronomies to improve biomass production from marginal lands in Europe. GCB Bioenergy 14, 710–734. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12935

Semple, W. S., Dowling, P. M., and Koen, T. B. (2008). Tall wheat grass (Thinopyrum ponticum) and puccinellia (Puccinellia ciliata) may not be the answer for all saline sites: a case study from the Central Western Slopes of New South Wales. Crop Pasture Sci. 59, 814–823. doi: 10.1071/AR07298

Sepehry, A., Akhzari, D., Pessarakli, M., and Barani, H. (2012). Studying the effects of salinity, aridity and grazing stress on the growth of various halophytic plant species (Agropyron elongatum, Kochia prostrata and Puccinellia distans). World Appl. Sci. J. 17, 1278–1286.

Shan, L., Li, C., Chen, F., Zhao, S., and Xia, G. (2008). A Bowman-Birk type protease inhibitor is involved in the tolerance to salt stress in wheat. Plant Cell Environ. 31, 1128–1137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01825.x

Shan, L., Zhao, S. Y., Chen, F., and Xia, G. M. (2006). Screening and localization of SSR markers related to salt tolerance of somatic hybrid wheat Shanrong No. 3. Sci. Agric. Sin. 39, 225–230. doi: 10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.at-2005-5571

Shannon, M. C. (1978). Testing salt tolerance variability among tall wheatgrass lines. Agron. J. 70, 719–722. doi: 10.2134/agronj1978.00021962007000050006x

Sheikh-Mohamadi, M. H., Etemadi, N., Aalifar, M., and Pessarakli, M. (2022). Salt stress triggers augmented levels of Na+, K+ and ROS, alters salt-related gene expression in leaves and roots of tall wheatgrass (Agropyron elongatum). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 183, 9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2022.04.022

Shen, Y. Y., Li, Y., and Yan, S. G. (2003). Effects of salinity on germination of six salt-tolerant forage species and their recovery from saline conditions. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 46, 263–269. doi: 10.1080/00288233.2003.9513552

Shen, Y., Li, Y., Yan, S., and Wang, S. (1999). Salt tolerance of early growth of five grass species in Hexi corridor. Acta Agrest Sin. 7, 293–299. doi: 10.11733/j.issn.1007-0435.1999.04.006

Smith, K. F. (1996). Tall wheatgrass (Thinopyrum ponticum (Podp.) Z. W. Liu & R. R. C. Wang): a neglected resource in Australian pasture. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 39, 623–627.

Sun, S., Che, N., Chen, L., Hao, Y., Xu, Y., Chen, Q., et al. (2025). Analysis wheat wild relatives Thinopyrum intermedium and Roegneria kamoji genomes reveal different polyploid evolution paths. Nat. Commun. 16, 7693. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-63007-y

Suyama, H., Benes, S. E., Robinson, P. H., Getachew, G., Grattan, S. R., and Grieve, C. M. (2007a). Biomass yield and nutritional quality of forage species under long-term irrigation with saline–sodic drainage water: field evaluation. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 135, 329–345. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2006.08.010

Suyama, H., Benes, S. E., Robinson, P. H., Grattan, S. R., Grieve, C. M., and Getachew, G. (2007b). Forage yield and quality under irrigation with saline–sodic drainage water: greenhouse evaluation. Agric. Water Manage. 88, 159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2006.10.011

Temel, S., Keskin, B., Simsek, U., and Yılmaz, İ.H. (2015). Performance of some forage grass species in halomorphic soil. Turk J. Field Crops 20, 131–141. doi: 10.17557/TJFC.82860

Thinopyrum intermedium v2.1 DOE-JGI. Available online at: http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/ (Accessed September 22, 2025).

Tian, H., Mu, Y., Yang, S., Zhang, J., Yang, X., Zhang, Q., et al. (2024). ATAC sequencing and transcriptomics reveal the impact of chromatin accessibility on gene expression in tritipyrum under salt-stress conditions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 228, 106014. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2024.106014

Tounsi, S., Giorgi, D., Kuzmanović, L., Jrad, O., Farina, A., Capoccioni, A., et al. (2024). Coping with salinity stress: segmental group 7 chromosome introgressions from halophytic Thinopyrum species greatly enhance tolerance of recipient durum wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1378186

Urbanavičiūtė, I., Bonfiglioli, L., and Pagnotta, M. A. (2021). One hundred candidate genes and their roles in drought and salt tolerance in wheat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6378. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126378

Wang, T., Cao, L., Liu, Z., Yang, Q., Chen, L., Chen, M., et al. (2022). Forage grass basic biology of constructing coastal grass belt. Chin. Bull. Bot. 57, 837–847. doi: 10.11983/CBB22165

Wang, R. R. C., Li, X. M., Hu, Z., Zhang, J. Y., Zhang, X. Y., Grieve, C. M., et al. (2003). Development of salinity-tolerant wheat recombinant lines from a wheat disomic addition line carrying a Thinopyrum junceum chromosome. Int. J. Plant Sci. 164, 25–33. doi: 10.1086/344556

Wang, M. C., Peng, Z. Y., Li, C. L., Li, F., Liu, C., and Xia, G. M. (2008). Proteomic analysis on a high salt tolerance introgression strain of Triticum aestivum/Thinopyrum ponticum. Proteomics 8, 1470–1489. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700569

Wang, J., Quan, T. Y., and Xia, G. M. (2004). Differences in the growth and contents of Na+ and K+ between somatic hybrid wheat and its wheat parent under salt stress. J. Trop. Subtrop Bot. 12, 355–358.

Wang, H., Sun, S., Ge, W., Zhao, L., Hou, B., Wang, K., et al. (2020a). Horizontal gene transfer of Fhb7 from fungus underlies Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Science 368, eaba5435.

Wang, W., Song, Y., Hu, W., Li, B., Zheng, Q., Li, Z., et al. (2020b). Comparison of biomass- accumulation–related traits in (common wheat × tall wheatgrass) F1 and its parents. Pratac Sci. 37, 1821–1832. doi: 10.11829/j.issn.1001-0629.2020-0001

Wei, L., Zhang, R., Zhang, M., Xia, G., and Liu, S. (2022). Functional analysis of long non-coding RNAs involved in alkaline stress responses in wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 73, 5698–5714. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erac211

Xiao, Q., Li, W., Hu, P., Cheng, J., Zheng, Q., Li, H., et al. (2025). An integrated method for evaluation of salt tolerance in a tall wheatgrass breeding program. Plants 14, 983. doi: 10.3390/plants14070983

Xu, Q., Tian, Z. R., Zhu, J. F., and Yu, L. (1998). Investigation of gene of K/Na discrimination character on 4E chromosome from Agropyron elongatum. Acta Bot. Boreal.-Occident Sin. 18, 504–507.

Xu, W., Wang, J., Liu, X., Xie, Q., Yang, W., Cao, X., et al. (2022). Scientific and technological reasons, contents and corresponding policies of constructing “Coastal Grass Belt“. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 37, 238–245. doi: 10.16418/j.issn.1000-3045.20210413001

Yang, Z., Mu, Y., Wang, Y., He, F., Shi, L., Fang, Z., et al. (2022). Characterization of a novel TtLEA2 gene from tritipyrum and its transformation in wheat to enhance salt tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.830848

Yang, R., Yang, Z., Peng, Z., He, F., Shi, L., Dong, Y., et al. (2021). Integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of tritipyrum provides insights into the molecular basis of salt tolerance. PeerJ 9, e12683. doi: 10.7717/peerj.12683

Yen, C. and Yang, J. (2022). “Biosystematics of genus lophopyrum”, in biosystematics of triticeae,” in Genera: campeiostachys, elymus, pascopyrum, lophopyrum, trichopyrum, hordelymus, festucopsis, peridictyon, and psammopyrum, vol. Volume V . Eds. Yen, C. and Yang, J. (China Agriculture Press and Springer, Beijing, China), 437–552. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-0015-0_4

Yuan, W. Y. and Tomita, M. (2015). Thinopyrum ponticum chromatin-integrated wheat genome shows salt tolerance at germination stage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 4512–4517. doi: 10.3390/ijms16034512

Zeng, J., Zhou, C., He, Z., Wang, Y., Xu, L., Chen, G., et al. (2023). Disomic substitution of 3D chromosome with its homoeologue 3E in tetraploid Thinopyrum elongatum enhances wheat seedlings’ tolerance to salt stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 1609. doi: 10.3390/ijms24021609

Zhang, R., Feng, X. H., Wu, Y. J., Sun, Q., Li, J., Li, J. S., et al. (2022a). Interactive effects of drought and salt stresses on the growth and physiological characteristics of Thinopyrum ponticum. CJEA 30, 1–12. doi: 10.12357/cjea.20220185

Zhang, B., Jacobs, B. C., O’Donnell, M., and Guo, J. (2005). Comparative studies on salt tolerance of seedlings for one cultivar of puccinellia (Puccinellia ciliata) and two cultivars of tall wheatgrass (Thinopyrum ponticum). Anim. Prod. Sci. 45, 391–399. doi: 10.1071/ea03156

Zhang, R., Liu, C. Z., Yuan, F., Liu, Y. L., Dong, D., Wang, S. N., et al. (2025a). Ion balance mechanism and transcriptome analysis of Elytrigia elongata in response to NaHCO3 stress. Acta Pratac Sin. 34, 174–186. doi: 10.11686/cyxb2024456

Zhang, Y., Tian, X. X., Zheng, M. L., Mao, P. C., and Meng, L. (2022b). Analysis of drought and salt resistance of EeHKT1;4 gene from Elytrigia elongata in Arabidopsis. Acta Pratac Sin. 31, 188–198. doi: 10.11686/cyxb2021304

Zhang, R., Zhong, R., Niu, K., Jia, F., Liu, Y., and Li, X. (2025b). Physiological and transcriptional regulation of salt tolerance in Thinopyrum ponticum and screening of salt-tolerant candidate genes. Plants 14, 2771. doi: 10.3390/plants14172771

Keywords: Thinopyrum, salt tolerance, distant hybridization, transcriptomics, proteomics, salt-responsive genes

Citation: Li W, Li H and Zheng Q (2025) Thinopyrum species as a genetic resource: enhancing salt tolerance in wheat and forage crops for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1728305. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1728305

Received: 19 October 2025; Accepted: 28 November 2025; Revised: 17 November 2025;

Published: 17 December 2025.

Edited by:

Junpeng Zhang, Shandong Agricultural University, ChinaReviewed by:

Zujun Yang, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, ChinaJianbo Li, The University of Sydney, Australia

Jian Zeng, Sichuan Agricultural University, China

Copyright © 2025 Li, Li and Zheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hongwei Li, aHdsaUBnZW5ldGljcy5hYy5jbg==

Wei Li

Wei Li Hongwei Li

Hongwei Li Qi Zheng

Qi Zheng