- School of Computer Science, Xijing University, Xi’an, China

Accurate detection of crop diseases from unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) imagery is critical for precision agriculture. This task remains challenging due to the complex backgrounds, variable scales of lesions, and the need to model both fine-grained spot details and long-range spatial dependencies within large field scenes. To address these issues, this paper proposes a novel Multiscale CNNState Space Model with Feature Fusion (MSCNN-VSS). The model is specifically designed to hierarchically extract and integrate multi-level features for UAVbased analysis: a dilated multi-scale Inception module is introduced to capture diverse local lesion patterns across different scales without sacrificing spatial detail; a Visual State Space (VSS) block serves as the core component to efficiently model global contextual relationships across the canopy with linear computational complexity, effectively overcoming the limitations of Transformers on high-resolution UAV images; and a hybrid attention module is subsequently applied to refine the fused features and accentuate subtle diseased regions. Extensive experiments on a UAV-based crop disease dataset demonstrate that MSCNN-VSS achieves state-of-the-art performance, with a Pixel Accuracy (PA) of 0.9421 and a mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) of 0.9152, significantly outperforming existing CNN and Transformer-based benchmarks. This work provides a balanced and effective solution for automated crop disease detection in practical agricultural scenarios.

1 Introduction

Global crop production is seriously threatened by various diseases such as aphids, powdery mildew and yellow rust, causing huge economic losses (Abbas et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023; Jia et al., 2025). Image segmentation of diseased leaves of crops is the key to disease detection and prevention (Xu et al., 2022a, 2022; Zhang et al., 2023). Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) remote sensing has become an important technical means for the detection and identification of large-scale crop diseases (Bouguettaya et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024; Shahi et al., 2023). It possesses obvious advantages, including high spatial resolution, operational flexibility, efficiency, and the ability to conduct rapid and low-cost monitoring of large areas under the conditions of high reliability and high data resolution (Maes and Steppe, 2019). The accurate detection of diseases from UAV imagery relies on advanced analytical methods. The field has evolved from traditional machine learning towards deep learning. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and U-Net architectures have demonstrated remarkable performance by automating feature learning (Qin et al., 2021; Kerkech et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2024; Zhang and Zhang, 2023). However, these models are inherently constrained by their limited receptive field, making it difficult to capture long-range dependencies and global contexts in crop disease images (Lei et al., 2021). This limits their ability to model correlations between distant lesions.

To overcome the receptive field limitation, Transformer-based models were introduced. They demonstrate the capability to handle inputs of varying dimensions and dynamically extract critical information through self-attention (De and Brown, 2023). Transformers can capture complex spatial dependency relationships between leaf lesions and healthy tissues, effectively identifying subtle spectral features of early diseases even under complex backgrounds (Singh et al., 2024). Frameworks like PD-TR (Wang J, et al., 2024) show significant advantages in cross-regional lesion correlation modeling. However, due to their quadratic complexity, Transformers impose a significant computational cost when processing high-resolution and high-dimensional UAV images.

Recently, Visual State Space (VSS) models have aroused great interest as an efficient alternative (Alonso et al., 2024). SSM-based Mamba models have shown great potential for long-range dependency modeling with linear complexity (Hu et al., 2024). By employing a state space mechanism, VSS models offer a more balanced approach for modeling both global contexts and local features in UAV crop disease detection. Architectures like VM-UNet (Ruan et al., 2024), Swin-UMamba (Shi et al., 2024), and Multiscale Vision Mamba-UNet (MSVM-UNet) (Hu et al., 2024) have demonstrated the potential of VSS blocks in segmentation tasks. Despite these promising developments, the potential of SSM and VSS architectures has rarely been fully exploited in UAV crop disease detection (Bouguettaya et al., 2023; Narmilan et al., 2022).

To bridge this gap, this paper constructs a multiscale CNN-VSS with feature fusion (MSCNN-VSS) for crop disease detection. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

1. A hybrid CNN-VSS architecture is constructed, providing a balanced solution for the segmentation of complex unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) crop disease images.

2. Collaboratively integrate multi-scale convolutional, VSS and hybrid attention modules, to enhance local feature diversity, capture global context dependencies, and optimize feature representation.

3. Extensive experiments were conducted on the dataset of crop disease images based on unmanned aerial vehicles.

The rest of this paper is arranged as follows. Section 2 introduces the proposed MSCNN-VSS, focusing on its main module design. Section 3 presents the experimental setup, benchmark results, and a comprehensive analysis including ablation studies and visualizations for welding defect segmentation. Finally, Section 4 concludes this paper.

2 The MSCNN-VSS model

The architecture of MSCNN-VSS is shown in Figure 1, consisting of Superpixel block, encoder, decoder, feature fusion module, and hybrid attention, where encoder and decoder are combined by skip connection to achieve better segmentation results with few annotation images. The main structures are shown in Figure 2, where VSS block derived from VMamba is the backbone of encoder and decoder, the dimension of the input image is W×H×3, and the output channel of encoder is 2i×C, C is often set to 96, and the output channel of decoder is the opposite of that of encoder, gradually decreasing.

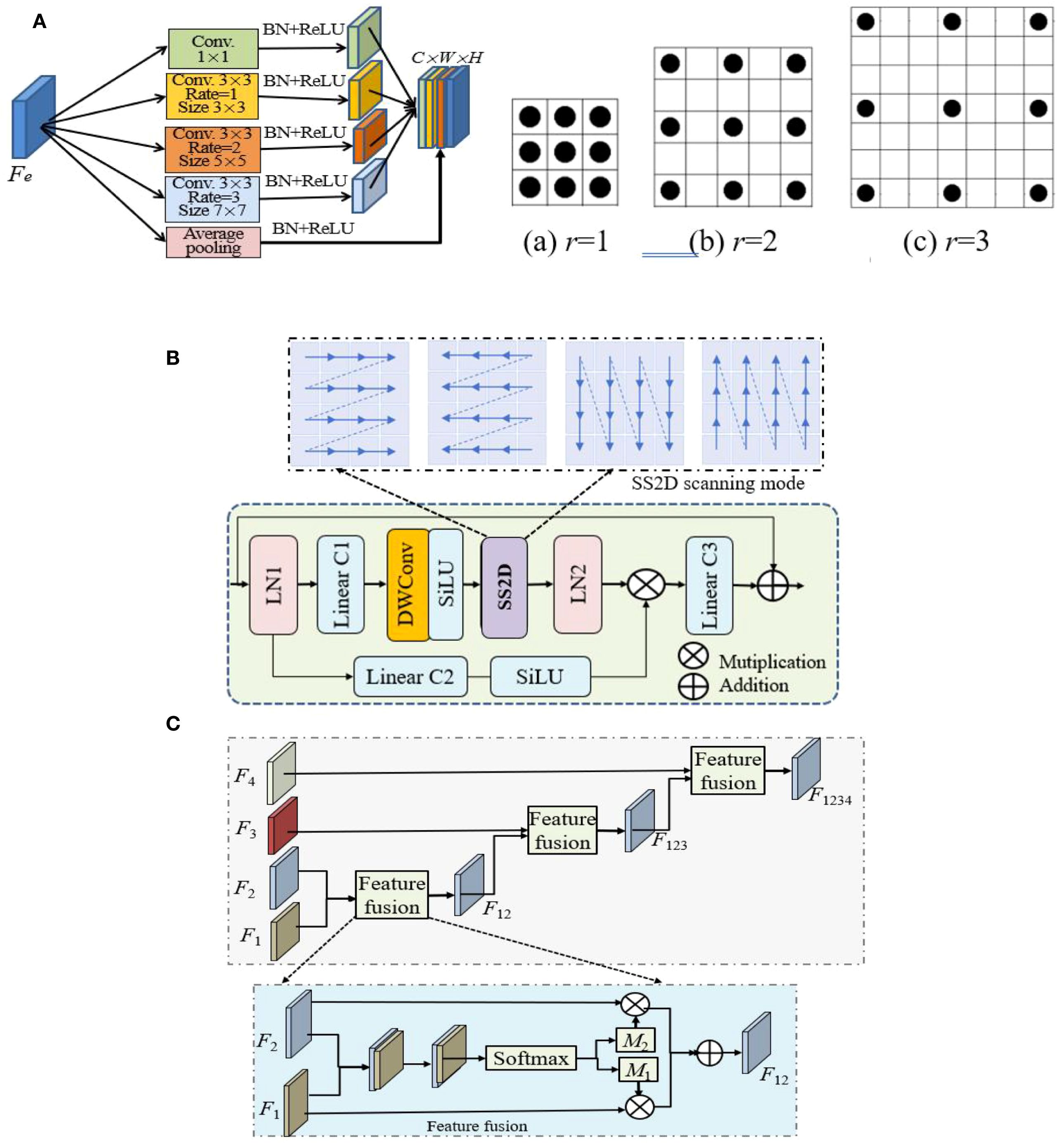

Figure 2. The structures of three main modules, where ⊕ and ⊗ indicate add and Hadamard product operations. (A) Multiscale Inception and its 3 dilated kernels (r = 1,2,3). (B) VSS. (C) Feature fusion.

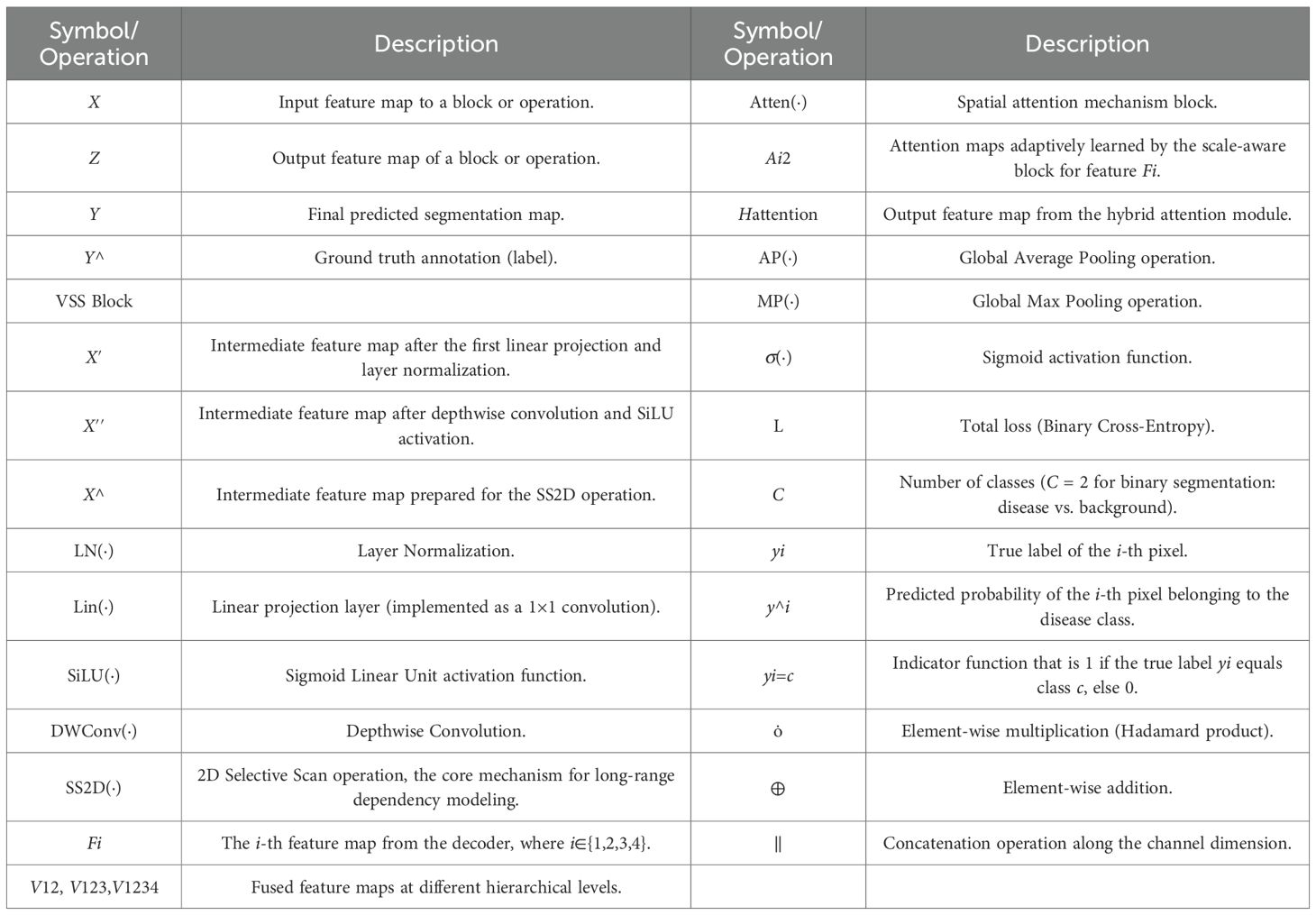

The notation and description of key mathematical symbols and operations are shown in Table 1.

The main processes of MSCNN-VSS are introduced in detail as follows.

1. Superpixel segmentation is performed using the Simple Linear Iterative Clustering (SLIC) algorithm from the OpenCV-Python library. We test different numbers of superpixels on images of diseased leaves (both close-up and distant views).

2. Segmenting diseased leaves in UAV imagery is challenging due to the high variability in lesion appearance. The pooling layers in standard U-Ne lose spatial detail, harming lesion localization. Therefore, a multi-scale dilated Inception module is introduced. Its structure is shown in Figure 2A, which is a series of parallel 3×3 convolution with dilated rates of {1,2,3}, exponentially increasing the receptive field (from 3×3 to 7×7) without increasing the weight parameters. After each dilated convolution, batch normalization (BN) and ReLU, the branched image feature details are concatenated and aggregated through 1×1 convolution to speed up the network training and convergence.

3. Encoder. Following patch embedding, the transformed features from the dilated Inception module are input into the encoder. The encoder is composed of VSS×2 blocks, whose fundamental operation is the 2D-selective-scan (SS2D). VSS is designed to overcome the limitations of standard models in capturing long-range dependencies in 2D imagery. Its architecture is depicted in Figure 2B and is detailed as show in Equation 1:

where are the input and output feature maps of MSVSS, LN(·), Lin(·), SiLU(·), MSSSM(·) and DWConv(·) are layer normalization, linear projecting, SiLU activation, MSSSM and DWConv operations, respectively.

SSM adopts the multiscan strategy to model long-range feature dependencies, which significantly increases the feature redundancy. Patch merging for 2× down-sampling in the encoder captures long-range dependencies while gradually reducing the spatial dimension, effectively compressing the input into multiscale representations.

4. Decoder. Like encoder, decoder consists of VSS and patch expanding blocks, where patch expanding is 2×up-sampling operation.

5. Feature fusion. Feature fusion is leveraged to integrate multi-scale features. It is commonly used in various deep learning models. Its structure is shown in Figure 2C. To manage the computational complexity, 1×1 convolution reshapes the feature mapping and standardizes the number of channels for decoder features to 64 at all scales. The module hierarchically integrates these multi-scale features using a spatial attention mechanism between adjacent scales. The integrated features from one level interact iteratively with those of the next, enabling adaptive multi-scale fusion. This process is described as show in Equation 2:

where Atten(.) denotes attention mechanism block, Fi, i∈{1, 2, 3, 4} are the ith features generated by the decoder and have been upsampled, with the same resolution, but different numbers of channels.

Taking V12 as an example, show in Equation 3:

where and are the attention maps adaptively learned by the scale-aware block, are concatenated and input into convolution and Softmax layers, the output is split along the channel dimension to obtain and .

(6) Hybrid attention. The integrated fusion feature V1234 is input into hybrid attention along the spatial dimension to aggregate the spatial information, generating two 1D average pooling and maxpooling maps, which are concatenated. Hybrid attention can enhance feature representation of the model, which is simply described as follows,

where and are the average pooling and maxpooling operations, respectively.

(7) Training model. Softmax classifier is used to detect crop diseases by Hatten from Equation 4. Classification binary cross entropy objective function is employed to measure the loss between the actual and the predicted detection distribution, defined as show in Equation 5:

where (i = 1,2,…,N) is a training image, is the ith pixel, is the feature representation of , is its corresponding label, N and C are the numbers of the pixel and corresponding class in the image, respectively, is the index function, C = 2 represents the detected result is binary image, containing defect pixel and background pixel.

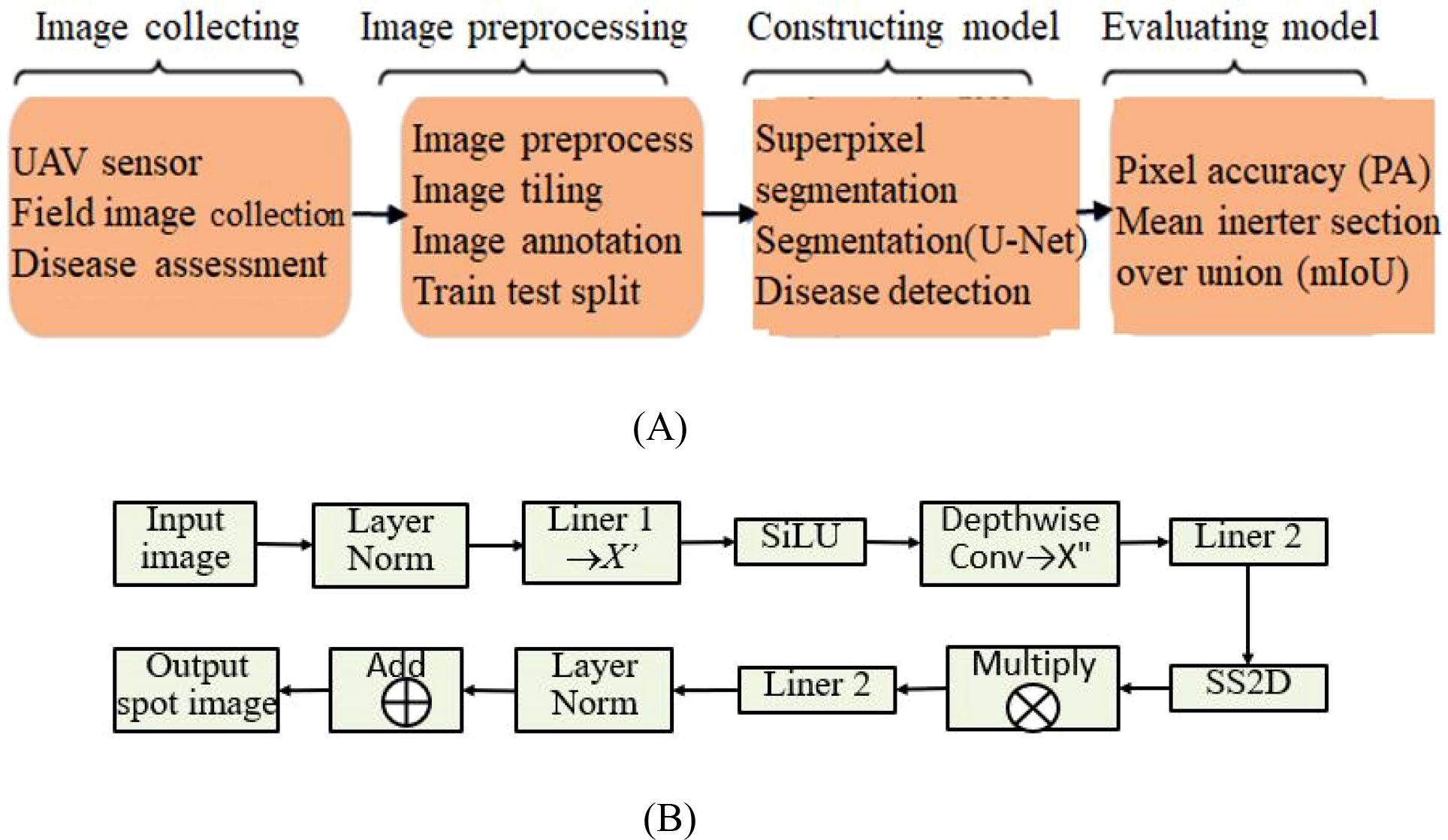

From the above analysis, the problem of using MSCNN-VSS and UAV images for crop disease detection is described as shown in Figure 3, including four stages: collecting images, image preprocessing, constructing model, and evaluating model.

Figure 3. The general process of MSCNN-VSS based crop disease detection using UAV imagery. (A) Stages. (B) Steps.

3 Experiment and analysis

The proposed MSCNN-VSS is extensively evaluated against six state-of-the-art models: Spatial-Context-Attention Network (SCANet) (Qin et al., 2021), an improved U-Net segmentation model with image processing (IUNet-IP) (Zhu et al., 2024), PD-TR (Wang H, et al., 2024), CMTNet (Guo et al., 2025), VM-UNet (Ruan et al., 2024), and Multiscale Vision Mamba-UNet (MSVM-UNet) (Hu et al., 2024). Brief descriptions of these comparative models are provided as follows.

SCANet is a spatial-context-attention network to identify disease based on UAV multi-spectral RSIs.

IUNet-IP is a hybrid architecture to identify leaf diseases and detect crops using deep learning and sophisticated image-processing techniques.

PD-TR is an end-to-end plant diseases detection using a Transformer.

CMTNet is a hybrid CNN-transformer network for UAV-based crop classification in precision agriculture.

VM-UNet is a Vision Mamba UNet for image segmentation.

MSVM-UNet is a multiscale VM-UNet for image segmentation.

3.1 UAV dataset preparation

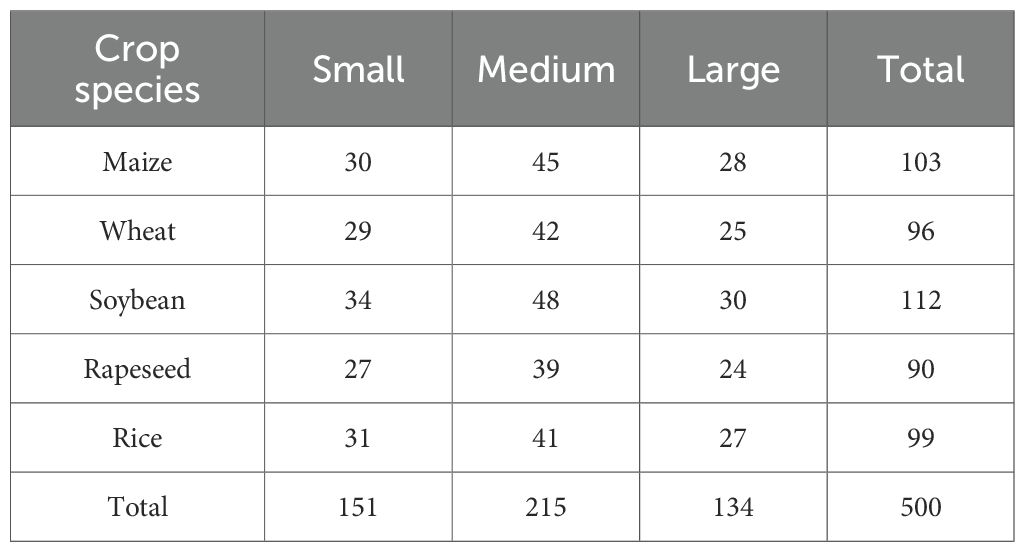

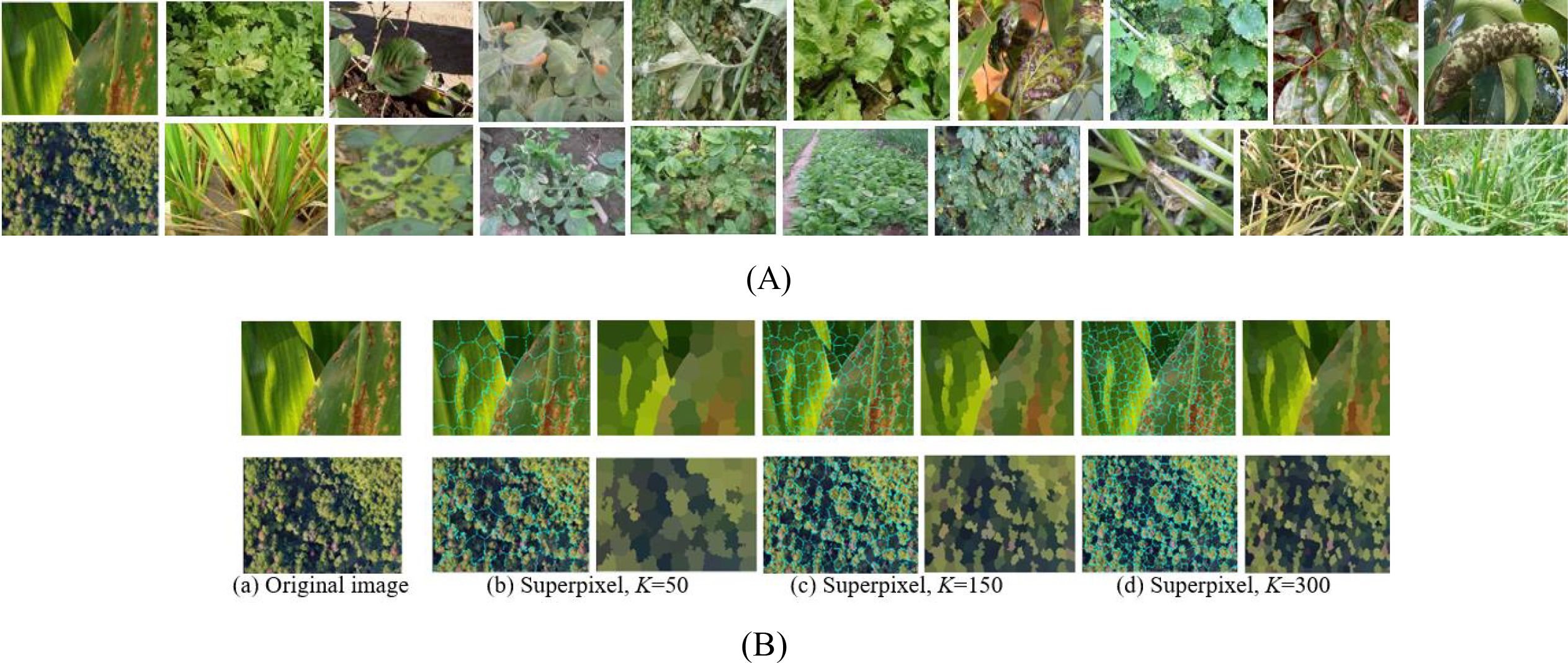

Sensors and cameras installed on UAVs were used to capture images of crop diseased leaves. The experimental dataset was constructed using a commercial Spreading Wing S1000+ UAV equipped with an RGB sensor, which captured images of rust-diseased leaves across multiple crop species. Data acquisition was conducted from July to September 2022 in the Yangling Agricultural Demonstration Zone, Xi’an, China. The UAV was operated at a constant altitude of 25 meters, yielding imagery with a ground resolution of approximately 1 cm/pixel. Each image has a resolution of 4000×3000 pixels at 72 dpi. The dataset comprises 500 high-resolution images collected under varied scenarios, lighting conditions, shooting angles, and backgrounds, as illustrated in Figure 4A. To ensure robust evaluation, the dataset was constructed with a balanced distribution across five major crop species and three disease severity levels. The severity was labeled by agronomy experts based on the visible percentage of leaf area affected: ‘Small’ (1-10%), ‘Medium’ (11-25%), and ‘Large’ (>25%). The detailed distribution of samples is shown in Table 2.

These samples cover maize, wheat, soybean, rapeseed, and rice 5 major crop species, with each crop category further divided into small, medium and large three severity levels. The detailed distribution is shown in Table below.

To ensure effective model training and evaluation, a five-fold cross-validation (FFCV) scheme was employed. The dataset was partitioned at the image level into five folds, ensuring that each fold maintained a nearly identical distribution of crop species and disease severity levels as the overall dataset (as shown in Table 2). This stratified splitting principle prevents bias and guarantees that each fold is representative of the entire data distribution. In each fold, 400 images (80%) were used for training, and the remaining 100 images (20%) served as an independent test set. The acquired images underwent preprocessing to eliminate background interference and noise. The Simple Linear Iterative Clustering (SLIC) method from the OpenCV-Python library was used for superpixel segmentation. We evaluated superpixel numbers in the range of [100, 300, 500]. Using 300 superpixels was selected as it preserved critical disease features without noticeable loss of spots while drastically reducing the computational load for subsequent analysis, as shown in Figure 4B. This setting was used for all experiments.

Figure 4. The rust diseased leaf image samples and superpixel images. (A) Diseased leaf image samples. (B) Superpixel images via three superpixel number.

3.2 Implementation details

To ensure a fair and reproducible comparison among all models, we established a unified training benchmark with fixed hyperparameters, data augmentation, and input resolution across all compared methods.

Input Preprocessing: All UAV images were first processed by the SLIC superpixel algorithm (with 300 superpixels) and then centrally cropped to a uniform resolution of 512×512 pixels to ensure consistent input dimensions across the network.

Data Augmentation: To enhance model robustness and prevent overfitting, a standard set of augmentation strategies was applied on-the-fly during training to all models. This included: random horizontal and vertical flipping (probability=0.5), random rotation (± 30 degrees), and random adjustments to brightness and contrast (variation factor=0.2).

Training Configuration: All models were trained from scratch under the same conditions:

Epochs 300, Batch Size 15, Optimizer Adam, Initial Learning Rate 0.001, Learning Rate Schedule Reduced by 50% every 500 iterations, Loss Function Weighted Cross-Entropy.

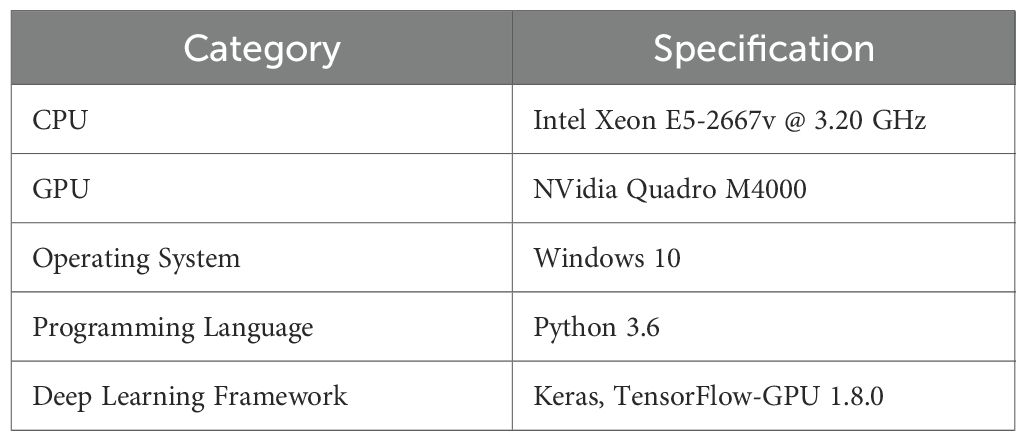

The network parameters were initialized using the Kaiming method. All experiments were conducted in the hardware and software environments shown in Table 3.

In addition to PA and mIoU, the following evaluation metrics are used to assess the model, where quantifies the computational cost in the reasoning process, and the model size indicates the storage requirements.

Evaluation Metrics: Pixel Accuracy (PA), mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), parameters (Params), computational complexity (FLOPs), and training time. PA and mIoU are calculated as show in Equations 6 and 7:

where N is the number of categories of image pixels, is the predicted and actual pixel of type i, is the total number of class i pixels, is the total number of pixels of actual type i and predicted type, mIoU is the mean Intersection over Union. The higher mIoU indicates the better match between the detected disease area and the actual disease area.

3.3 Experiment results

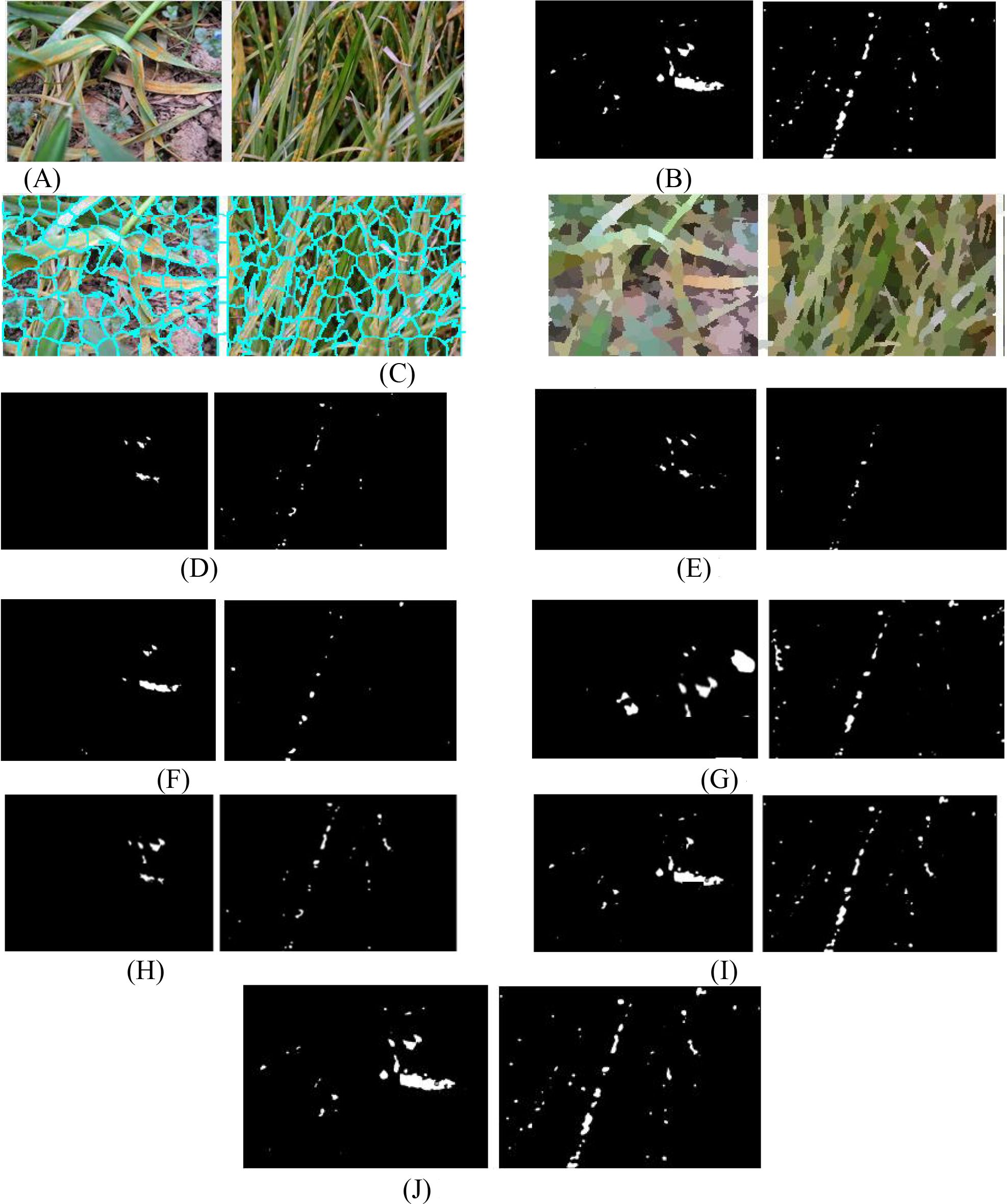

Figures 5A and B show two UAV-captured close-range images of rust-infected leaves and their corresponding annotated ground truths. Figure 5C displays the superpixel segmented results by SLIC, which divide the spot area into structurally meaningful components. Comparative segmentation results in Figures 5D-J demonstrate the performance of SCANet, IUNet-IP, PD-TR, CMTNet, VM-UNet, MSVM-UNet, and the proposed MSCNN-VSS, respectively.

Figure 5. The detected spots of 7 models. (A) Original rice disease images. (B) Ground truth annotations. (C) Superpixel images. (D) SCANet. (E) IUNet-IP. (F) PD-TR. (G) CMTNet. (H) VM-UNet. (I) MSV-UNet. (J) MSCNN-VSS.

Figure 5 illustrates the segmentation performance of the compared models on two close-range UAV images of rust-infected leaves (Figure 5A) and their SLIC superpixel results (Figure 5C). While all models can detect disease spots under challenging conditions, MSCNN-VSS (Figure 5J) achieves the best results, identifying minute spots with minimal false positives due to its VSS block and feature fusion module, which enhance multi-scale feature representation. SCANet and IUNet-IP (Figures 5D, E) show significant false positives, while VM-UNet and MSVM-UNet (Figures 5H, I) capture broader lesions but lack boundary precision.

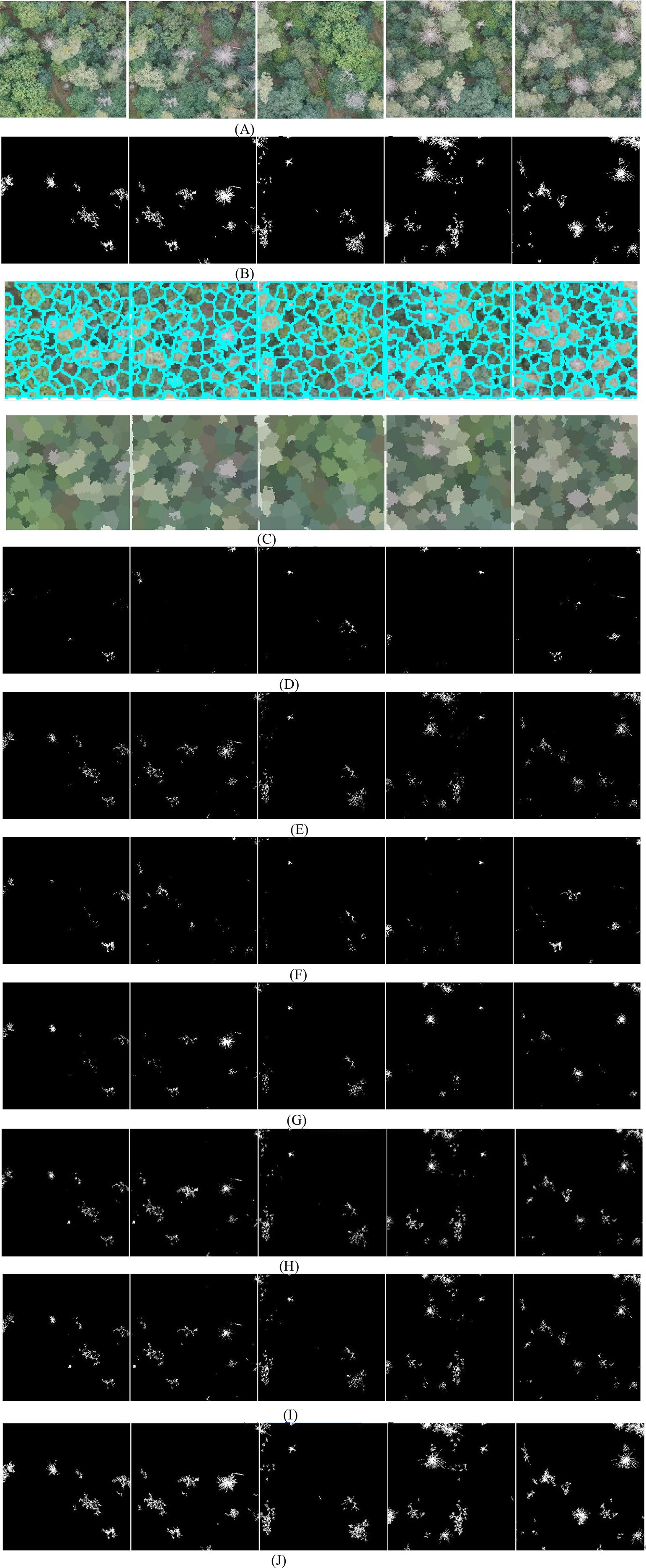

To further evaluate the performance of MSCNN-VSS, experiments are conducted on the diseased leaf images captured by UAVs at long distances. The comparative detection results of the 7 models are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The detected spots of 7 models. (A) Original disease images. (B) Ground truth annotations. (C) Superpixel images. (D) SCANet. (E) IUNet-IP. (F) PD-TR. (G) CMTNet. (H) VM-UNet. (I) MSV-UNet. (J) MSCNN-VSS.

From Figure 6, it is found that on long-distance UAV images with complex backgrounds and weaker lesion characteristics, the performance of the 7 models shows significant differentiation, where SCANet and IUNet-IP generate a large number of background false detections and loss a lot of spots, PD-TR and CMTNet seriously miss detections of small lesions. Although VM-UNet and MSVM-UNet can maintain the basic structure, the boundary positioning is ambiguous. In contrast, the proposed MSCNN-VSS achieves the most complete capture and the complete boundary characterization of fine lesions while maintaining the lowest false detection rate. Its multi-level feature fusion mechanism and hybrid attention design effectively overcome the problem of feature attenuation in long-distance imaging.

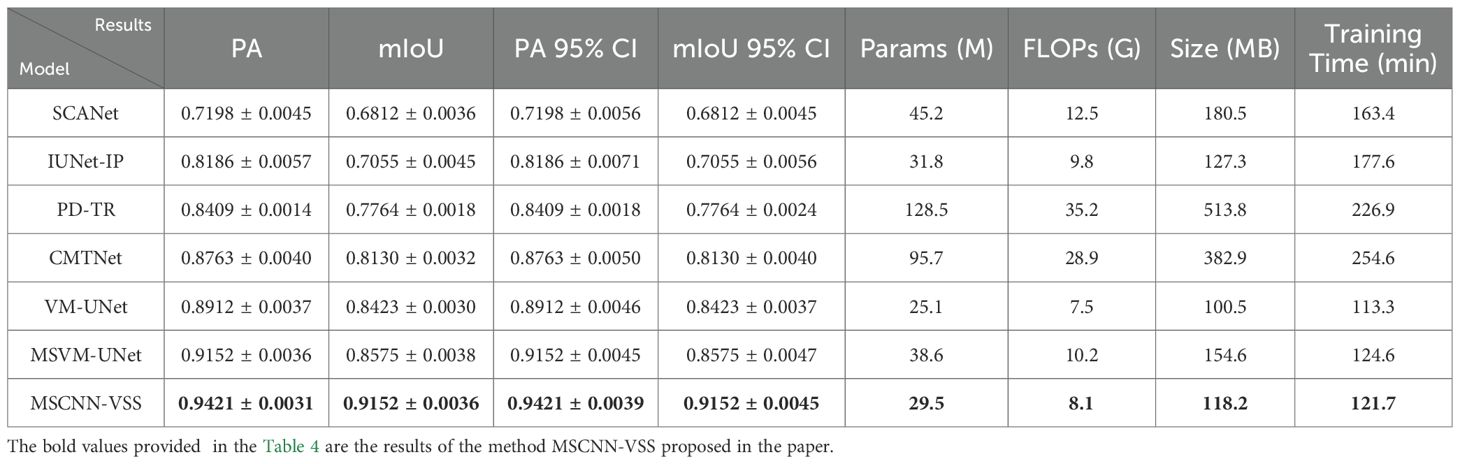

To further validate the disease detection performance of the proposed model, the seven comparative models are evaluated using PA, mIoU, Parameters, FLOPs, Model size and average model-training time as objective metrics. Comparative experimental results (mean ± standard deviation) are shown in Table 4, where 95% Confidence Interval (95% CI) for PA and mIoU is based on the five-fold cross-validation.

As shown in Table 4, the model MSCNN-VSS demonstrates an excellent balance between performance and efficiency. This model achieved the optimal results in segmentation accuracy (PA: 0.9421, mIoU): (0.9152), the number of parameters (29.5M) and computational complexity (8.1G FLOPs) are significantly lower than those of Transformer-based models (such as PD-TR and CMTNet), and its model size (118.2MB) is also much smaller than these models, which demonstrates the advantages of the model. Compared with the benchmark model VM-UNet, which is also part of the VSS series, this model achieved a significant improvement of over 5% in mIoU with only a 17.5% increase in parameters and an 8% increase in computational load. This excellent balance between accuracy and efficiency makes MSCNN-VSS particularly suitable for deployment and application in practical agricultural scenarios with limited computing resources.

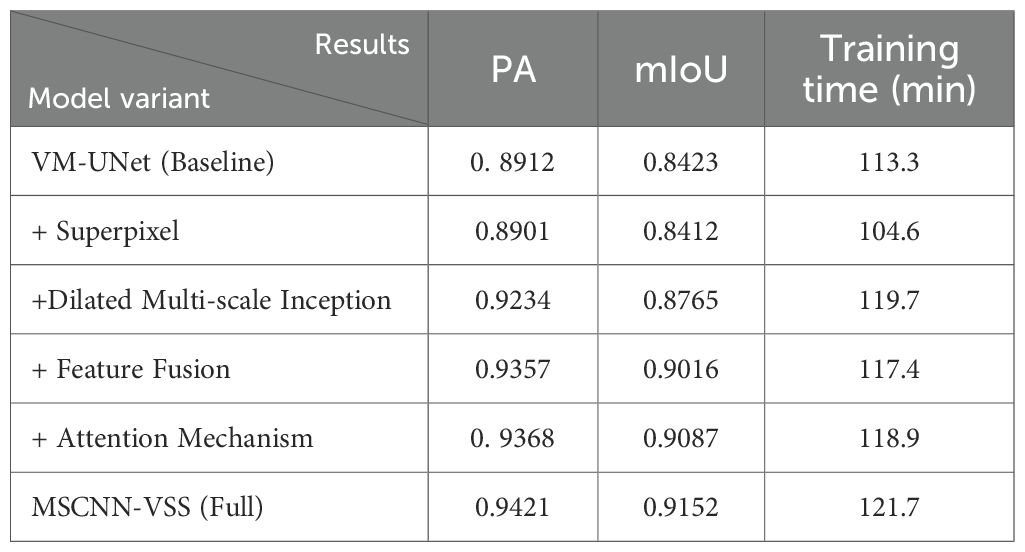

Based on the VM-UNet baseline, we progressively integrate four key components: Superpixel segmentation, dilated multi-scale Inception modules, advanced feature fusion mechanisms, and attention mechanisms, to quantitatively evaluate their individual and collective contributions to the final detection performance. This structured ablation study meticulously analyzes improvements in PA, mIoU, and training/inference efficiency, demonstrating that our architectural enhancements achieve significant performance gains while maintaining computational feasibility. The results are shown in Table 5.

The ablation results in Table 5 illustrate the progressive performance improvements contributed by each component of the MSCNN-VSS architecture. While the superpixel module slightly degrades detection accuracy, it brings notable computational efficiency. The dilated multi-scale Inception module delivers the most substantial gain, significantly increasing both PA and mIoU. Combining feature fusion and attention mechanisms further enhances detection accuracy, with the attention mechanism particularly improving fine-grained detection capability as reflected in the remarkable mIoU improvement. By synergistically combining all components, the complete model achieves the optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency, attaining the highest scores (0.9421 PA, 0.9152 mIoU) with only a 7.4% increase in training time compared to the baseline, thereby validating the effectiveness of the MSCNN-VSS architectural design.

3.4 Results analysis

The above experimental results ultimately verified that each component plays a role in improving the model’s accurate disease detection ability. The complete MSCNN-VSS structure achieves the best balance between accuracy and efficiency. As shown in Table 2, this model has achieved the most advanced results, with a pixel accuracy of 0.9421 and a mIoU of 0.9152. It is far superior to all comparison methods such as CMTNet (0.8763 PA, 0.8130 mIoU) and the original VM-UNet (0.8912PA, 0.8423 mIoU). This significant performance improvement is achieved while maintaining outstanding training efficiency, requiring 121.7 minutes of training time, which is nearly 50% less than that of CMTNet (254.6 minutes) and only 7.4% more than the VM-UNet baseline (113.3 minutes). The ablation experiment results further verify the effectiveness of each architectural component, particularly highlighting the crucial role of the dilated multi-scale Inception module and attention mechanism in capturing complex pathological features while maintaining computational efficiency. These findings jointly verify that MSCNN-VSS is effective and feasible for crop disease detection through optimal balance accuracy and practicality.

4 Conclusion and future work

This paper proposed a novel MSCNN-VSS model to address the challenges of crop disease detection in UAV imagery. The hybrid architecture effectively combines multi-scale CNN, VSS, and attention mechanisms to achieve a superior balance between segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency. Extensive experiments confirmed that our model outperforms several state-of-the-art benchmarks. The model is effective for enabling practical, large-scale crop disease monitoring in precision agriculture, facilitating timely and targeted pest management. However, it has limitations: the dataset is constrained to five crops and only rust diseases, performance under extreme environmental conditions (e.g., heavy rain, dense cloud cover) remains untested, and residual complexity hinders direct deployment on low-power devices. Future work will focus on extending the model to multi-disease classification and developing lightweight versions for edge deployment, as outlined in the Discussion section, explore lightweight versions of the architecture for mobile deployment to handle high-resolution UAV image data.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

TZ: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft. DW: Data curation, Validation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Formal analysis. WC: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research were funded by Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Provincial Department of Science and Technology (2025NC-YBXM-216,2025GH-YBXM-077) and Development Support Project of Shaanxi Provincial Department of Education (24JR158,24JR159).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbas, A., Zhang, Z., Zheng, H., Alami, M., Alrefaei, A., Qamar Abbas, Q., et al. (2023). UAVs in plant disease assessment, efficient monitoring, and detection: A way forward to smart agriculture. Agronomy 13, 1524. doi: 10.3390/agronomy13061524

Alonso, C., Sieber, J., and Zeilinger, M. (2024). State space models as foundation models: A control theoretic overview. Am. Control Conf., 146–153. doi: 10.23919/ACC63710.2025.11107969

Bouguettaya, A., Zarzour, H., Kechida, A., and Taberkit, A. (2023). A survey on deep learning-based identification of plant and crop diseases from UAV-based aerial images. Cluster Computing 26, 1297–1317. doi: 10.1007/s10586-022-03627-x, PMID: 35968221

De, S. and Brown, D. (2023). Multispectral plant disease detection with vision transformer–convolutional neural network hybrid approaches. Sensors 23, 8531. doi: 10.3390/s23208531, PMID: 37896623

Guo, X., Feng, Q., and Guo, F. (2025). CMTNet: a hybrid CNN-transformer network for UAV-based hyperspectral crop classification in precision agriculture. Sci. Rep. 15, 12383. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-97052-w, PMID: 40216979

Hu, C., Cao, N., Zhou, H., and Guo, B. (2024). Medical image classification with a hybrid SSM model based on CNN and transformer. Electronics. 13, 3094. doi: 10.3390/electronics13153094

Jia, Y., Li, Y., He, J., Biswas, A., Siddique, K., Hou, Z., et al. (2025). Enhancing precision nitrogen management for cotton cultivation in arid environments using remote sensing techniques. Field Crops Res. 321, 109689. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2024.109689

Kerkech, M., Hafiane, A., and Canals, R. (2020). Vine disease detection in UAV multispectral images using optimized image registration and deep learning segmentation approach. Comput. Electron. Agric. 174, 105446. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2020.105446

Lei, S., Luo, J., Tao, X., and Qiu, Z. (2021). Remote sensing detecting of yellow leaf disease of Arecanut based on UAV multisource sensors. Remote Sens 13, 4562. doi: 10.3390/rs13224562

Li, D., Yang, S., Du, Z., Xu, X., Zhang, P., Yu, K., et al. (2024). Application of unmanned aerial vehicle optical remote sensing in crop nitrogen diagnosis: A systematic literature review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 227, 109565. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2024.109565

Maes, W. and Steppe, K. (2019). Perspectives for remote sensing with unmanned aerial vehicles in precision agriculture. Trends Plant Sci. 24, 152–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2018.11.007, PMID: 30558964

Narmilan, A., Gonzalez, F., Salgadoe, A., and Powell, K. (2022). Detection of white leaf disease in sugarcane using machine learning techniques over UAV multispectral images. UAVs 6, 230. doi: 10.3390/UAVs6090230

Qin, J., Wang, B., and Wu, Y. (2021). Identifying pine wood nematode disease using UAV images and deep learning algorithms. Remote Sens. 13, 162. doi: 10.3390/rs13020162

Ruan, J., Li, J., and Xiang, S. (2024). VM-UNet: vision mamba UNet for medical image segmentation. arXiv:2402.02491. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2402.02491

Shahi, T., Xu, C., Neupane, A., and Guo, W. (2023). Recent advances in crop disease detection using UAV and deep learning techniques. Remote Sens. 15, 2450. doi: 10.3390/rs15092450

Shi, Y., Dong, M., and Xu, C. (2024). Multiscale VMamba: hierarchy in hierarchy visual state space model. arXiv:2405.14174. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2405.14174

Singh, A., Rao, A., Chattopadhyay, P., Maurya, R., and Singh, L. (2024). Effective plant disease diagnosis using Vision Transformer trained with leafy-generative adversarial network-generated images. Expert Syst. Appl. 254, 124387. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124387

Wang, H., Nguyen, T., Nguyen, T., and Dang, M. (2024). PD-TR: End-to-end plant diseases detection using a Transformer. Comput. Electron. Agric. 224, 109123. doi: 10.3390/electronics13153094

Wang, J., Zhang, S., Lizaga, I., Zhang, Y., Ge, X., Zhang, Z., et al. (2024). UAS-based remote sensing for agricultural Monitoring: Current status and perspectives. Comput. Electron. Agric. 227, 109501. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2024.109501

Xu, C., Wang, X., and Zhang, S. (2022b). Dilated convolution capsule network for apple leaf disease identification. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1002312, PMID: 36388492

Xu, C., Yu, C., and Zhang, S. (2022a). Lightweight multi-scale dilated U-net for crop disease leaf image segmentation. Electronics 11, 3947. doi: 10.3390/electronics11233947

Zhang, S., Wang, D., and Yu, C. (2023). Apple leaf disease recognition method based on Siamese dilated Inception network with less training samples. Comput. Electron. Agric. 213, 108188. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2023.108188

Zhang, S. and Zhang, C. (2023). Modified U-Net for plant diseased leaf image segmentation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 204, 107511. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2022.107511

Keywords: crop disease detection, superpixel segmentation, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), Visual StateSpace (VSS), multiscale CNN-VSS with feature fusion (MSCNN-VSS)

Citation: Zhang T, Wang D and Chen W (2025) Multiscale CNN-state space model with feature fusion for crop disease detection from UAV imagery. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1733727. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1733727

Received: 28 October 2025; Accepted: 25 November 2025; Revised: 22 November 2025;

Published: 17 December 2025.

Edited by:

Zhiqiang Huo, Queen Mary University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Jun Liu, Weifang University of Science and Technology, ChinaXingzao Ma, Lingnan Normal University, China

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Wang and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ting Zhang, enRwYXBlcjI1QDE2My5jb20=

Ting Zhang

Ting Zhang Dengwu Wang

Dengwu Wang