- 1Institute of Plant Protection and Agro-Products Safety, Anhui Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hefei, China

- 2Australian Herbicide Resistance Initiative, School of Agriculture and Environment, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA, Australia

The evolution of herbicide resistance in weedy plants leads to various adaptation traits including flowering time and seed germination. In our previous studies, we found an association of the early flowering phenotype with the ACCase inhibitor herbicide resistance genotype in a population of Polypogon fugax. MADS-box transcription factors are known to play pivotal roles in regulating plant flowering time. In this study, a SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE (SVP)-like gene, belonging to the StMADS11 subfamily in the MADS-box family, was cloned from the early flowering P. fugax population (referred to as PfMADS16) and resistant to the herbicide clodinafop- propargyl. Overexpression of the SVP-like gene PfMADS16 in Arabidopsis thaliana resulted in early flowering and seed abortion. This is consistent with the phenotypic characters of resistant P. fugax plants, but contrary to the conventional role of SVP-like genes that usually suppress flowering. In addition, down regulation of the seed formation gene AtKTN1 in flowers of PfMADS16 transgenic Arabidopsis plants indicates that PfMADS16 may be indirectly associated with seed viability. Furthermore, one protein (PfMADS2) from the APETALA1 (AP1) subfamily interacting with PfMADS16 in P. fugax was identified with relevance to flowering time regulation. These results suggest that the PfMADS16 gene is an early flowering regulation gene associated with seed formation and viability in resistant P. fugax population. Our study provides potential application of PfMADS16 for integrated weed management (such as genetic-based weed control strategies) aiming to reduce the soil weed seedbank.

Introduction

Herbicide weed control is the dominant and most intensive selective force imposed in modern agriculture, resulting in widespread evolution of herbicide resistance in many weed species worldwide (Heap, 2020). Herbicide-resistant plants exhibit changes in leaf canopy shape (Bravo et al., 2017), plant size and growth rate (VanEtten et al., 2016; Bravo et al., 2017), flowering time and seed germination rate (Wang et al., 2010) compared to susceptible counterparts. Stress-induced flowering is the third category of flowering response, in addition to photoperiodic flowering and vernalization (Takeno, 2016). In recent years, there have been increasing reports of early flowering in herbicide-resistant populations (Zhu et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2015). For example, a Hordeum glaucum biotype resistant to ACCase-inhibiting herbicides flowered earlier than the susceptible biotype in the field and exhibited reduced seed production in competition with Lens culinaris (Shergill et al., 2016). A glyphosate-resistant population of Conyza bonariensis flowered 28 days earlier and had higher seed germination and production than the susceptible population (Kaspary et al., 2017).

It is well established that flowering is controlled by multiple regulatory genes and pathways and is influenced by environmental conditions (Mouradov et al., 2002; Srikanth and Schmid, 2011). Plant MADS-box transcription factors are key regulators of many developmental processes. MADS-box genes can be classified into 14 clades: StMADS11, AGL17, AGL12, TM3, FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), AGL6, AGL2, SQUA, AG, TM8, OsMADS32, DEF/GLO, GGM13, and AGL15 (Gramzow and Theissen, 2013; Chen et al., 2017). The StMADS11 subfamily (isolated from Solanum tuberosum L.) of MADS-box genes is predominantly expressed in vegetative tissues and plays important roles in vegetative development and flower transitioning in diverse plant species (Carmona et al., 1998; Cohen et al., 2012; Cooke et al., 2012). The StMADS11 subfamily contains AGAMOUS-Like 24 (AGL24) and SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE (SVP) genes (Becker and Theissen, 2003) that are involved in the regulation of inflorescence structure and floral organ building (Smith et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2013). SVP usually acts as a repressor of the transition to flowering (Hartmann et al., 2000), while AGL24 acts as a promoter of this process in Arabidopsis (Michaels et al., 2003). Genes of the StMADS11 family have been identified in various plant species with variable functions. Among the three StMADS11-like genes (OsMADS22, OsMADS47, and OsMADS55) in rice, only OsMADS55 controls flowering time when expressed in Arabidopsis (Fornara et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2012). Overexpression of kiwifruit SVP3 in Actinidia eriantha affects reproductive development, causing abnormal flower, fruit and seed development (Wu et al., 2014). Although extensive research has been carried out on crop plants, little is currently known about flowering time gene regulation in weedy plant species in relation to herbicide resistance.

In our previous research we found that clodinafop-propargyl resistance in a Polypogon fugax population (R) is associated with an early flowering phenotype relative to the susceptible population (S) (Tang et al., 2015). Transcriptome analysis identified a flowering-related contig (CL4600.contig2, thereafter named PfMADS16) belonging to the StMADS11-subfamily of the MADS-box gene family that had significantly higher expression at the flowering stage in R vs. S P. fugax (Zhou et al., 2017). We hypothesized that this gene may be involved in early flowering in P. fugax, despite its established role in the suppression of flowering in Arabidopsis (Li et al., 2008). In the current study, we transformed A. thaliana with PfMADS16, and found it caused early flowering. More importantly, overexpression of the PfMADS16 gene in Arabidopsis resulted in some pods with aborted seeds, which is similar to observations in R P. fugax plants. Furthermore, one interacting protein (PfMADS2) with high homology to Lolium temulentum MADS2 was also highly expressed in R P. fugax during the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. Therefore, PfMADS16 is likely involved in early flowering and abnormal seed formation in R P. fugax population by interacting with PfMADS2. To our knowledge, this is the first report revealing a StMADS11-like gene PfMADS16 that is related to both early flowering regulation and seed abortion in herbicide resistant weed species.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Seeds of the clodinafop-propargyl resistant population of P. fugax (referred to as R) were collected from Qingsheng County (29° 54′ 1″ N, 103° 48′ 57″ E), Sichuan Province, China. An herbicide susceptible P. fugax population (S) was sampled from a non-cultivated area in Xichang City in Sichuan (27° 50′ 56″ N, 102° 15′ 53″ E). The R and S P. fugax populations were characterized in our previous studies (Tang et al., 2014, 2015). In this current study, seeds of the fourth generation of the R and S populations were used that were generated by self-crossing in isolation. The seedlings were transplanted into individual 1 L pots containing potting medium (1:1:1:2 vegetable garden soil/compost/peat/dolomite) after germination. Plants were grown in a glasshouse under natural sunlight with average temperatures of 20/10°C (day/night).

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh Columbia (Col) was purchased from the SALK collection1 for transgenic manipulation. Arabidopsis seedlings were transplanted into individual 0.25 L pots containing potting medium (1:1:4 vermiculite/perlite/sphagnum) and were grown at 20°C at 100 μmol m–2 s–1 photo density under cool white fluorescent light with a photoperiod of 16/8 h (long day condition, LD) or 8/16 h, light/dark (short day, SD).

Gene Cloning, Molecular Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of PfMads16 cDna From P. fugax

In our previous study, we found that the CL4600.Contig2 showed significantly higher expression in R vs. S populations at the reproductive growth stage (Zhou et al., 2017). The open reading frame (ORF) of the contig sequence was predicted using the ORF finder software2, and the full-length ORF was cloned using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. Isolation of total RNA from R and S P. fugax populations and reverse transcription were performed using commercial kits [Takara Biomedical Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd.]. The amplified full-length cDNA fragment was then ligated into the pMD18-T vector, and confirmed as a homologous gene of the StMADS11 subfamily based on sequence homology, namely, PfMADS16.

Phylogenetic analysis was implemented using the MEGA software version 5.0, and the robustness of the inferred phylogeny was validated by including 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Plasmid Construction and Arabidopsis Transformation

The plasmid vectors pCAMBIA2300 and pCAMBIA1303 were digested by HindIII and EcoRI, respectively. The (CaMV) 35S promoter of pCAMBIA2300 (1,008 bp) and the large skeleton of pCAMBIA1303 were recovered and purified. Then, T4 DNA ligase (TaKaRa) was used to connect the two parts, and a new two-element expression vector pCAMBIA1303-35S:35ST (referred to as the empty plasmid control, Mock) including the 35S promoter was obtained.

The full-length ORF of the PfMADS16 gene was ligated into the control vector pCAMBIA1303-35S:35ST to generate the plasmid pCAMBIA1303-35S-35ST: PfMADS16 (Supplementary Figure S1A). The plasmid was transferred into WT Arabidopsis plants (Col) using the floral dipping method mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. All transgenic Arabidopsis seeds (T0) were screened on 1/2 MS solid medium containing 50 mg-L–1 hygromycin. After germination, T1 transgenic lines (n = 40) were verified by PCR amplification of the hygromycin gene and histochemical localization of the GUS gene (Supplementary Figure S1B). Introduction of the target gene (PfMADS16) was verified by PCR in positive T2 generation plants (n = 36), which all showed an early flowering phenotype compared to the WT. Therefore, the four T2 lines differing slightly in flowering time were used to produce four T3 lines for the following experiments.

Flowering Time and Seed Production in Transgenic Arabidopsis and Seed Activity Measurement in P. fugax

To measure flowering time, untransformed WT, empty plasmid control (Mock) and transgenic plants (PfMADS16) were placed on MS agar medium after being surface sterilized with 10% hypochlorite, and were stratified at 4°C for 48 h before being placed at room temperature (22°C). Ten-day-old seedlings (four leaves) were transferred to growth medium (1:1:4 of vermiculite, perlite and sphagnum) and grown under LD (16 h light) or SD (8 h light) conditions.

The flowering times of 20 plants from four T3 transgenic lines were recorded from the day of transplanting until the first flower bloomed. Rosette leaves were counted at the peduncle (2 cm) stage, and the above-ground plant height and total pod numbers were determined on day 55 after transplanting. Seeds were collected on day 62 after transplanting and weighed after drying at 37°C for 24 h.

Seed viability in R and S P. fuax was tested using the TTC (triphenyltetrazolium chloride) method. The seeds were soaked in warm water (30°C) for 6 h, cut in half and placed in 0.2% TTC in darkness at 30°C for 24 h. After washing three times with distilled water, color development in the seed endosperm was immediately examined under a stereomicroscope.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay in R P. fugax

The yeast two-hybrid library of R P. fugax (cloned into the prey vector pGADT7) was constructed by selecting three P. fugax R plants randomly at the early flowering stage and using the Matchmaker® Gold Yeast Two-Hybrid System (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Full-length PfMADS16 was cloned into vector pGBKT7 (bait vector) and then transformed into the yeast strain Y2HGold using the YeastmakerTM Yeast Transformation System 2 (Clontech).

The constructed R P. fugax yeast two-hybrid library was used to screen the interaction proteins of PfMADS16 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Matchmaker® Gold Yeast Two-Hybrid System). The primers used for pGBKT7 vector construction are listed in Supplementary Table S1. To confirm protein interactions, the screened prey and bait vectors were validated by one-to-one interaction hybridization.

Gene Expression Analysis in Arabidopsis and P. fugax

To analyze the expression pattern of PfMADS16 in different tissues of transgenic Arabidopsis plants, plants from the two T3 transgenic lines (35S:PfMADS16 1# and 2#) were used. Leaf and flower samples were collected at the seedling (6–8 leaves) and flowering (full open) stages, and root, stem and pod samples were collected at the podding stage. Harvested samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for later use.

The whole above-ground parts of PfMADS16 transgenic (35S:PfMADS16 1# and 2#) and WT plants were collected at their respective flowering stage for analysis of the expression patterns of four Arabidopsis endogenous genes FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), SUPPRESSOR OF CONSTANS OVEREXPRESSION1 (SOC1), FLOWERING LOCU C (FLC), and LEAFY (LFY), relevant to flowering regulation, and one gene (AtKTN1) relevant to seed formation regulation.

To compare the expression pattern of PfMADS16 and its interacting protein (PfMADS2) in R and S P. fugax plants at each developmental stage, tissue samples of the R and S P. fugax plants (n = 3) were collected at the seedling and tillering stages, and the samples collected at the early flowering stage of R plants corresponded to the heading stage of the S plants.

Total RNA was extracted using the SGTriEx Total RNA extract Kit (SinoGene), and DNA contamination was removed by RNase-free DNase (Fermentas). The DNA-free RNA was then used for reverse transcription using a Thermo First cDNA Synthesis Kit (SinoGene). The ACTIN2 and EF1 genes were used for the normalization of Arabidopsis and P. fugax samples, respectively. The primer sequences used for RT-qPCR are provided in Supplementary Table S1. The qPCR was conducted for up to 40 cycles using the following thermal profile: denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 55°C for 15 s and extension at 72°C for 45 s. The RT-qPCR results were expressed as means ± SE of three biological replicates each performed in triplicate. Gene expression was calculated as 2–ΔΔCt.

Results

Sequence Analysis of PfMADS16 cDNA From P. fugax

The PfMADS16 coding sequence (651 bp, GenBank accession MN101552) was the same in R and S P. fugax plants, encoding a 216-amino acid protein with 86, 84, and 82% identity to known SVP like genes Festuca arundinacea VRT2 (ADK55060.1), Festuca pratensis MADS-box transcription factor MADS16 (ADW23676.1) (Ergon et al., 2013), and Lolium perenne MADS16 (AAZ17551.1), respectively. However, PfMADS16 only showed 50, 45, and 32% protein identity with SVP, AGL24, and SOC1 in Arabidopsis, respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis of PfMADS16 and SVP/StMADS11-like genes from plant species showed that PfMADS16 clustered closely to the SVP-like genes of F. pratensis MADS16 (ADW23676.1) and L. perenne MADS16 (AAZ17551.1), and rice OsMADS22, OsMADS55 and OsMADS47 (Sentoku et al., 2005), Dimocarpus longan DlSVP, Arabidopsis SVP, Aquilegia formosa AfSVP.2, and Magnolia praecocissima MpMADS1. They all clustered in the SVP/StMADS11-like group (Supplementary Figure S2A). This shows that PfMADS16 most likely belongs to the SVP group, which includes the SVP homologs (NP_179840.2) from Arabidopsis. This group is distinct from Arabidopsis AGL24 and SOC1 proteins (Supplementary Figure S2A). Sequence alignments revealed that PfMADS16 has a conserved MADS-box domain and SVP motif (Supplementary Figure S2B). Thus, PfMADS16 appears to be an SVP/StMADS11-like transcription factor.

Overexpression of PfMADS16 in Arabidopsis Induces Early and Prolonged Flowering, and Abnormal Seed Development

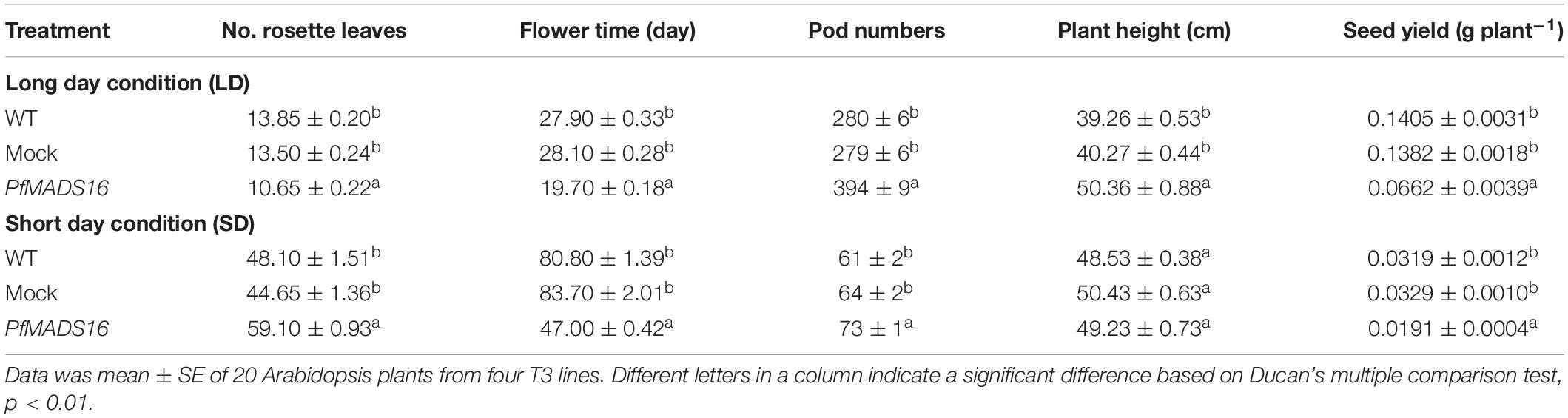

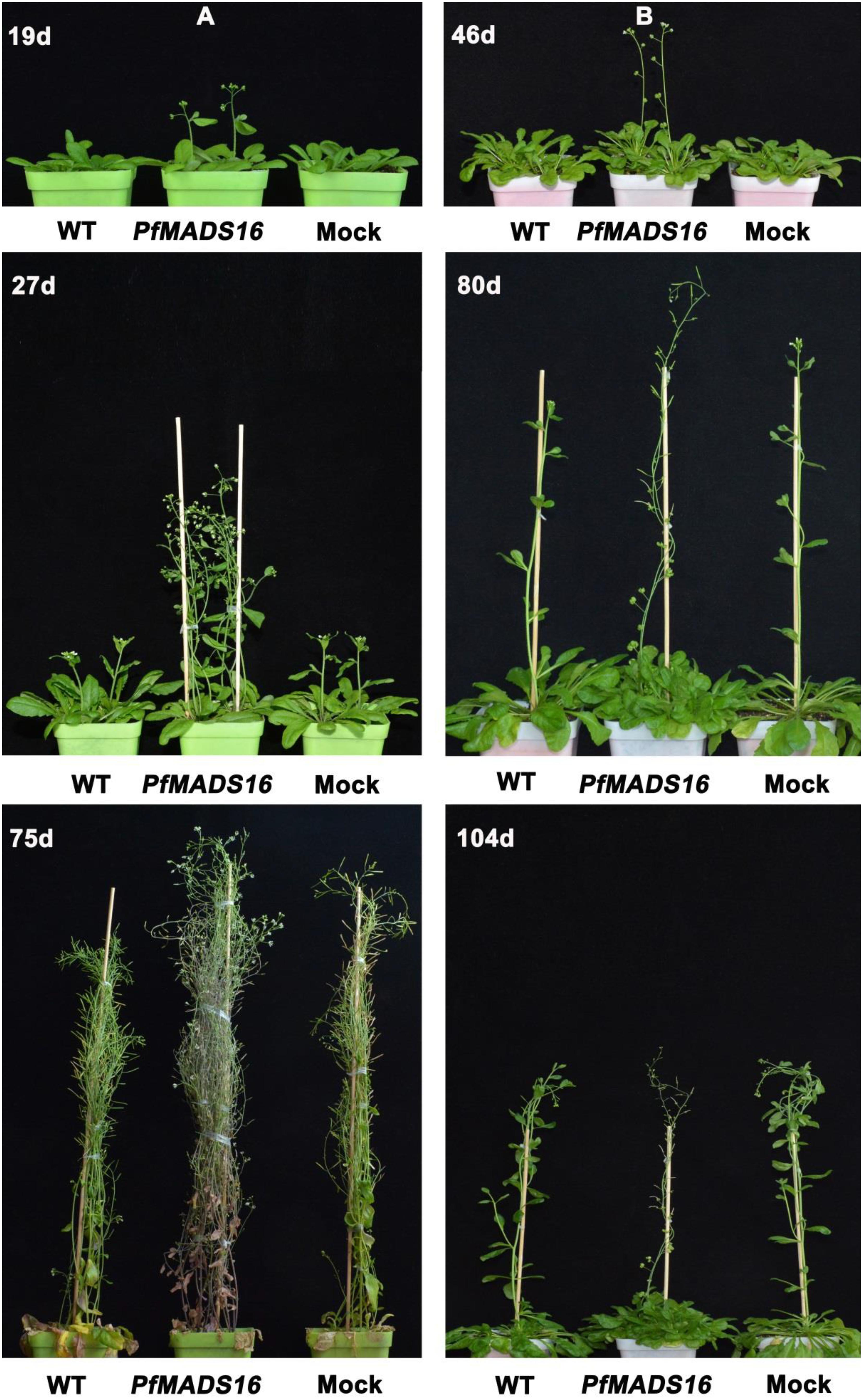

Arabidopsis PfMADS16 T3 transgenic plants flowered 7–9 days earlier and produced 3–4 fewer rosette leaves than WT and Mock plants under the LD conditions (Table 1 and Figure 1A). Under the SD conditions. PfMADS16 transgenic plants flowered ~25–42 days earlier but produced 9–13 more rosette leaves than control plants (Table 1 and Figure 1B). The flowering period of PfMADS16 transgenic plants lasted significantly longer than the controls under the LD conditions, and while all the control plants produced pods, the PfMADS16 transgenic plants were still producing new flowers (Figure 1A, 75 days).

Table 1. Changes in growth and reproduction of Arabidopsis thaliana overexpressing the PfMADS16 gene under long day (LD) and short day (SD) conditions.

Figure 1. Flowering phenotypes of representative PfMADS16 transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants under long day (LD) (A) and short day (SD) conditions (B) in comparison to untransformed WT and Mock transgenic plants. Photos were taken 19, 27, and 75 days after transplanting under the LD conditions, and 46, 80, and 104 days after transplanting under SD conditions.

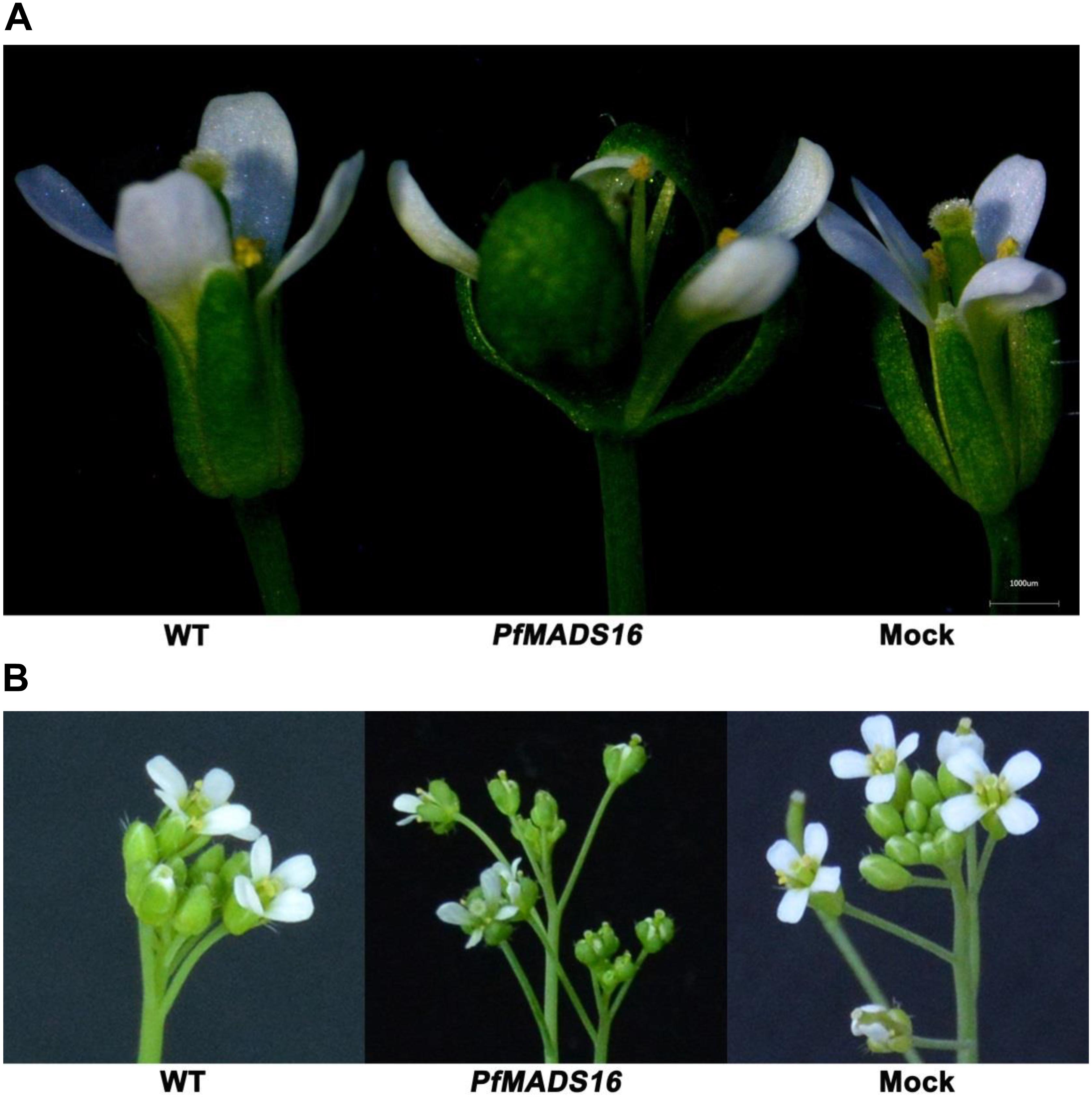

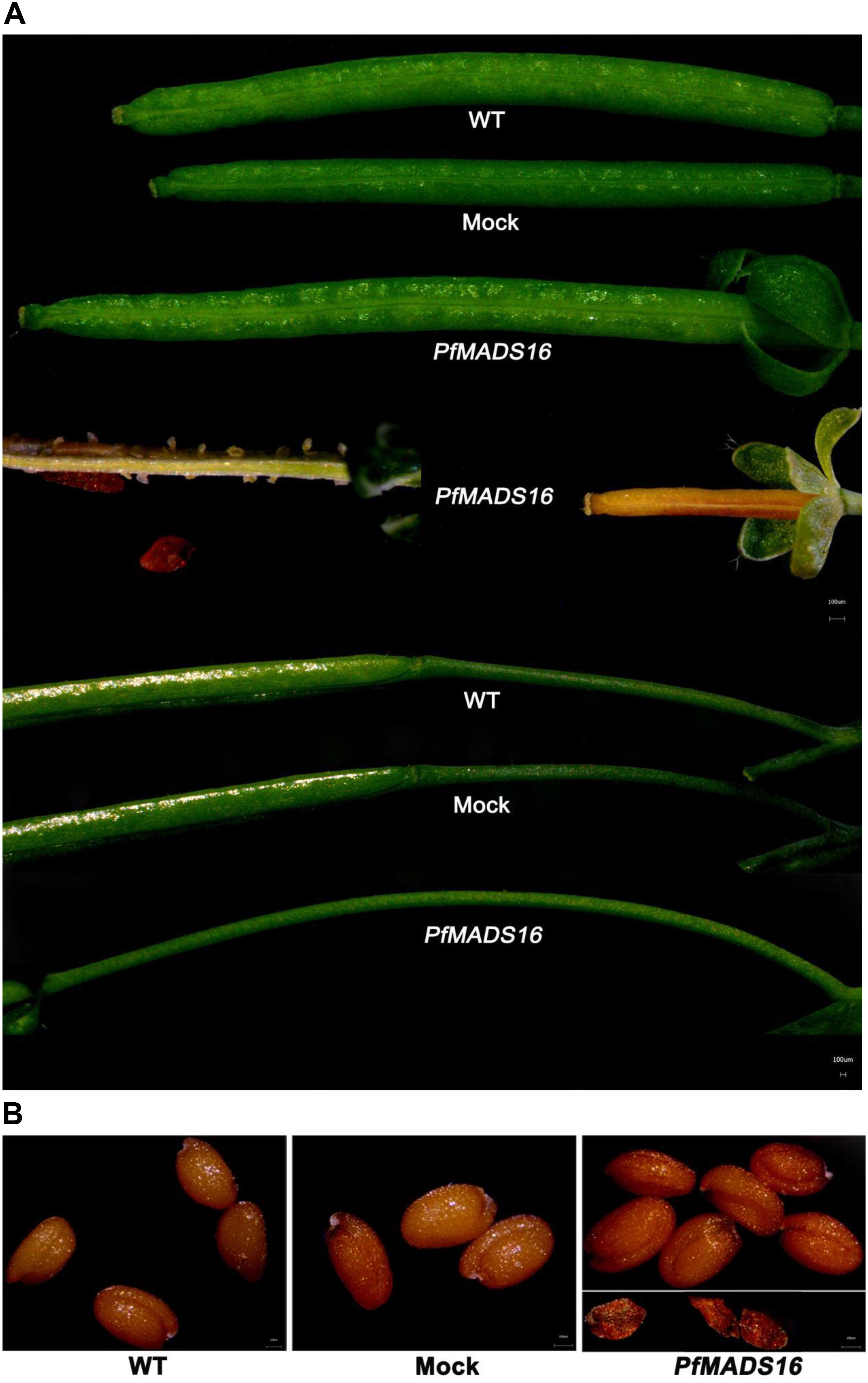

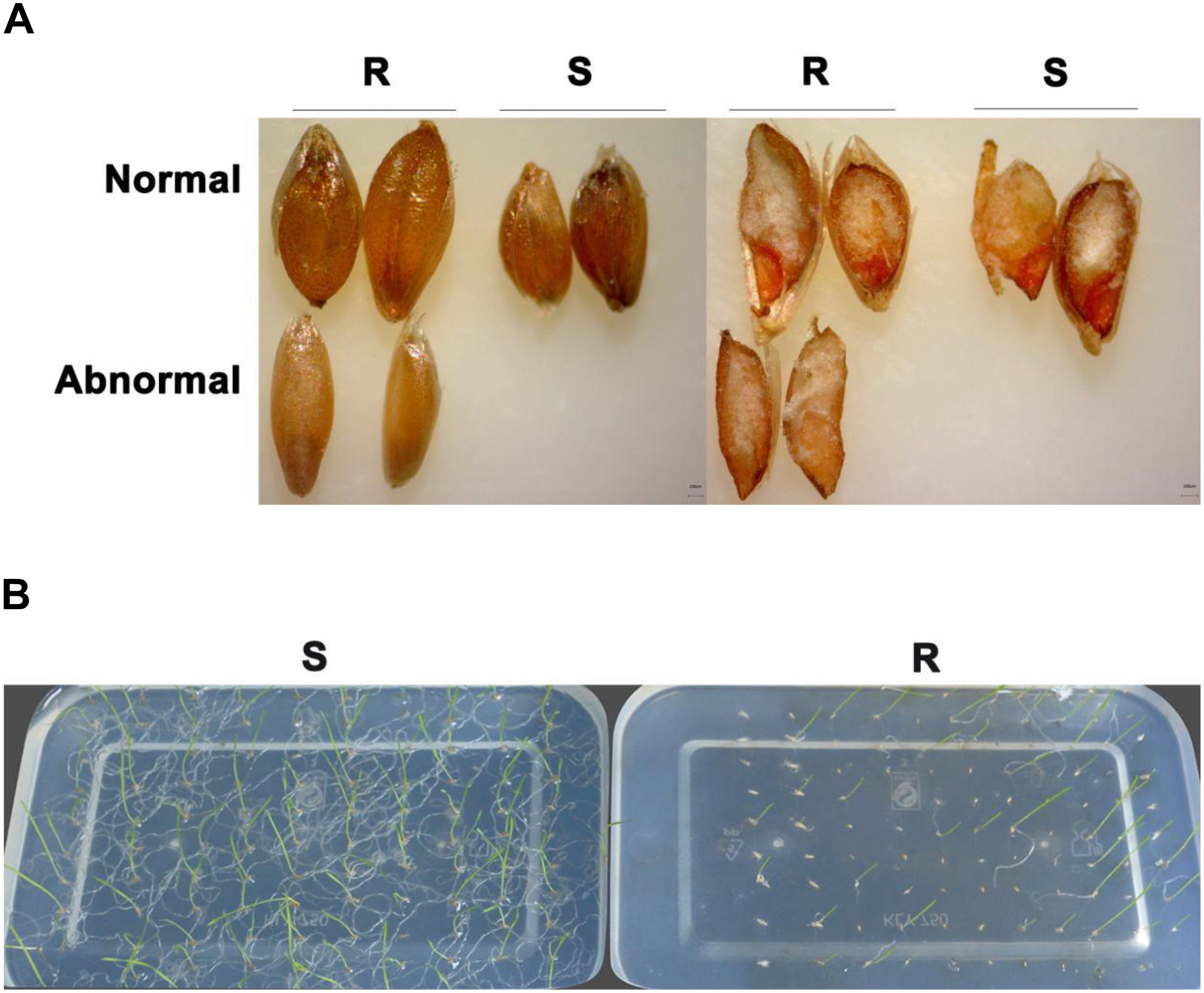

In contrast to control plants, the flowering pattern of PfMADS16 transgenic plants became choripetalous (Figures 2A,B), with sepals wider and rounder than normal that did not fall off even when the pods were mature; in addition, the length of the peduncle was markedly increased (Figure 3A). Interestingly, single PfMADS16 transgenic plants produced two types of pods: normal ones similar to WT, and abnormal ones (more than half of the total pods) with aborted seeds (Figure 3B). This was similar to the R P. fugax plants that also had two types of seeds: normal ones similar to the S P. fugax seeds, and the abnormal ones with a low endosperm content and lack of seed viability (Figure 4A). There was a significant difference in the 100-grain weight (7.7 vs. 9.4 mg, p < 0.05) between R and S P. fugax, and R seeds had a lower percentage germination rate than the S seeds (Figure 4B). Although PfMADS16 transgenic Arabidopsis plants were taller and had more total pods than WT, seed production was significantly lower than the control plants (Table 1). Thus, overexpression of PfMADS16 in Arabidopsis resulted in a phenotype with early-flowering and seed abortion.

Figure 2. Representative phenotype changes in flowers of PfMADS16 transgenic Arabidopsis plants in comparison to WT and Mock plants. (A) Morphological differences of a single flower. (B) Morphological differences of the inflorescence. Flower phenotype changers among transgenic lines are similar.

Figure 3. Phenotypic abnormalities in podding of representative PfMADS16 transgenic Arabidopsis plants as compared to WT and Mock plants. (A) PfMADS16 transgenic plants exhibiting different pod types (long and short), sepals that do not fall off at maturity, and elongated pedicels. (B) PfMADS16 transgenic plants with aborted seeds. Similar results were observed among T3 transgenic lines.

Figure 4. Comparison of seed vigor and the germination rate between resistant (R) and susceptible (S) of Polypogon fugax. (A) Seed appearance (left) and the seed embryo activity test by the TTC method (right) in R and S plants. (B) Seed germination (23 day) of R and S plants on 0.6% agar at 15°C.

Expression Pattern of PfMADS16 and Endogenous Genes Involved in Flowering and Seed Formation in Transgenic Arabidopsis

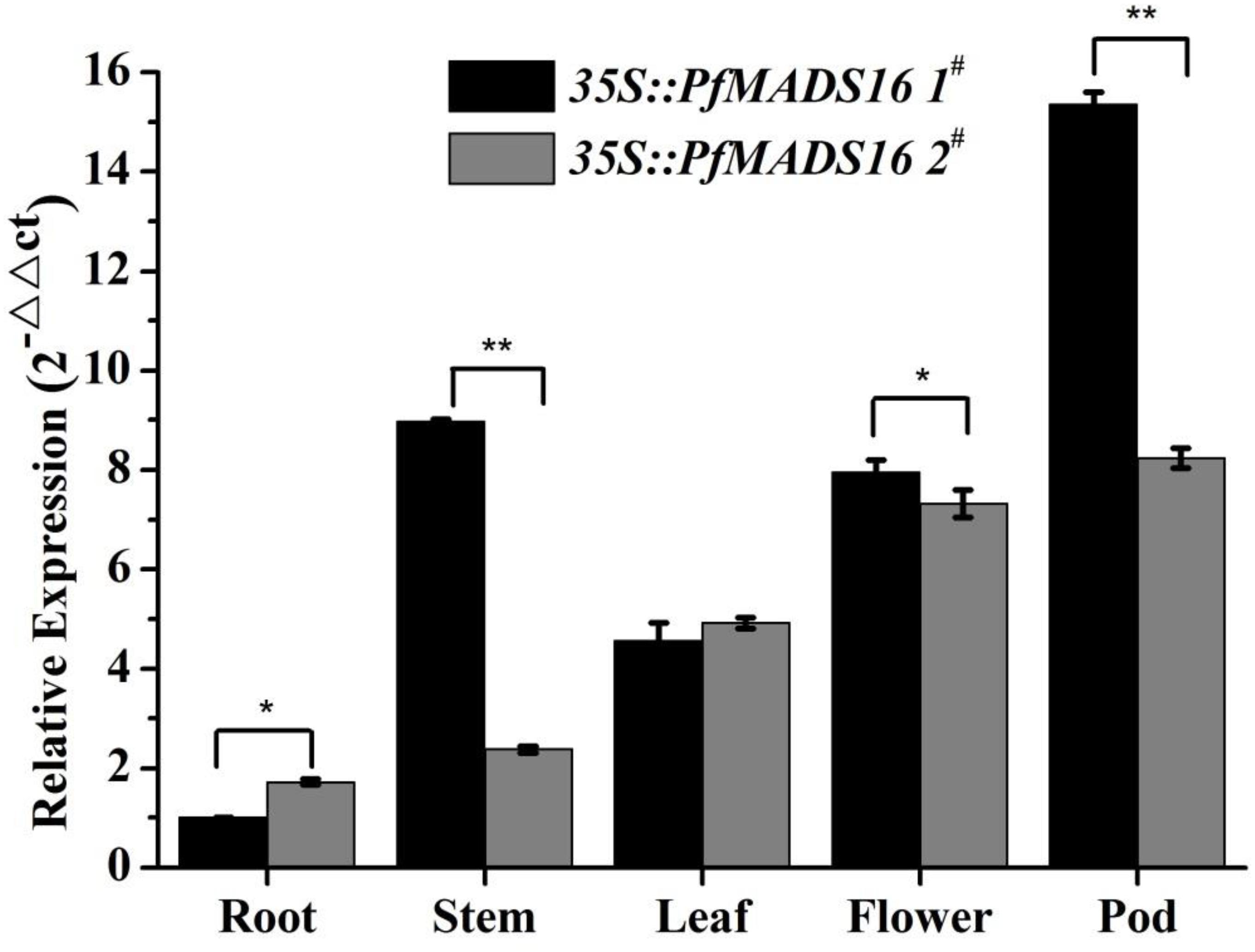

The expression of PfMADS16 in different tissues of transgenic Arabidopsis plants was analyzed by RT-qPCR. Results from the two T3 lines are similar showing that PfMADS16 were expressed in almost all of the tissues examined, with relatively higher transcript levels in the pods, flowers and leaves than in the roots (Figure 5). Therefore, a high level of PfMADS16 expression in flowers and pods might contribute to flowering and pod development.

Figure 5. RT-qPCR analysis of PfMADS16 gene expression in different tissues of plants from two T3 transgenic Arabidopsis lines. Error bars represent standard error calculated from three biological replicates. An actin homologous gene (ACTIN2) of Arabidopsis was used as an internal control. *indicates significant difference, p < 0.05; **indicates significant difference, p < 0.01.

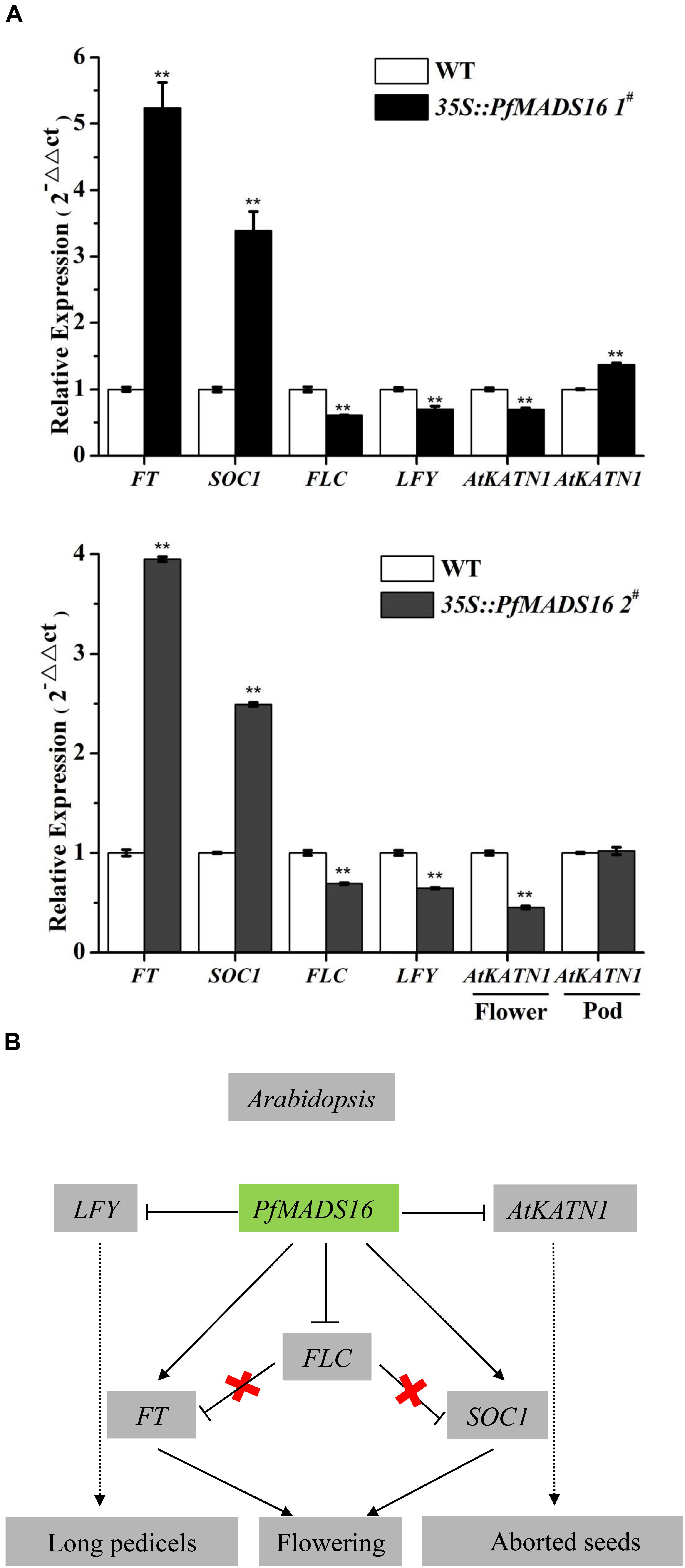

The expressions of FT and SOC1 were also higher, while those of FLC and LFY were lower in above-ground material of both lines of PfMADS16 transgenic Arabidopsis plants compared to the controls (Figure 6A). In addition, the expression of AtKTN1 was significantly lower in flowers, and higher in pods of 35S:PfMADS16 1# (but not in the 35S:PfMADS16 2#) plants compared to the WT control (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Overexpression of PfMADS16 promotes flowering in Arabidopsis. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of PfMADS16 and the four endogenous flowering-related genes (FT, SOC1, FLC, LFY) in whole above-ground material of the two transgenic Arabidopsis lines and WT at the early flowering stage, analysis of AtTKN1 in flowers and pods of transgenic and WT plants. The ACTIN2 gene was used as an internal control. ** indicates significant difference, p < 0.01. (B) Proposed model of flowering induction in PfMADS16 transgenic Arabidopsis plants. FLC, Flowering locus C; SOC1, Suppressor of over-expression of CO1; FT, Flowering locus T; LFY, LEAFY; Arrow, enhanced expression; Horizontal line, inhibited expression; Cross, interrupted expression; Dotted line, indirect promotion.

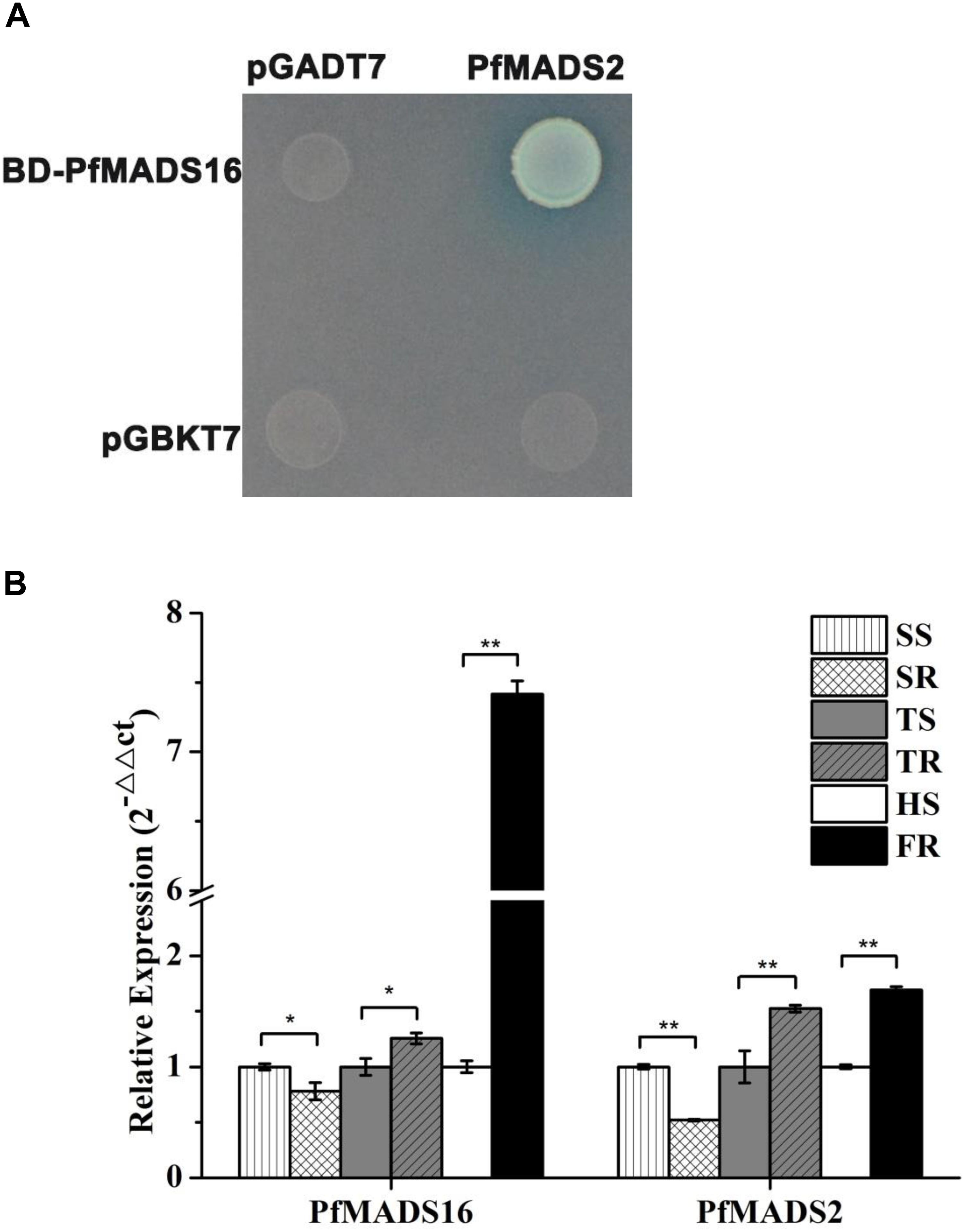

Expression Pattern of PfMADS16 and the Interacting Protein in P. fugax

One MADS family protein (named PfMADS2) that interacted with PfMADS16 in R P. fugax was identified by the yeast two-hybrid analysis and was validated (Figure 7A). The protein showed 94.7, 94.3, and 90.2% sequence identity to L. perenne MADS-box protein 2 (MADS2) (AAO45874.1), L. temulentum MADS2 (AF035379. 1), and Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii MADS-box transcription factor 15-like (XP_020149442.1), respectively (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 7. The yeast two-hybrid and expression assays. (A) Protein interaction was indicated by the ability of yeast cells to grow on synthetic dropout medium lacking Leu/Trp/His/Ade. Genes for PfMADS16 and the interaction protein (PfMADS2) were cloned into pGBKT7 (shown as BD) and pGADT7 (shown as AD), respectively. (B) RT-qPCR analysis of PfMADS16 and PfMADS2 in the resistant population of P. fugax. * indicates significant difference, p < 0.05; ** indicates significant difference, p < 0.01. SR, Resistant plants at the seedling stage; SS, Susceptible plants at the seedling stage; TR, Resistant plants at the tillering stage; TS, Susceptible plants at the tillering stage; FR, Resistant plants at the flowering stage; HS, Susceptible plants at the heading stage.

The expression patterns of PfMADS16 and the interacting protein (PfMADS2) were compared at the seedling and tillering stages between R and S plants. In addition, the expression patterns of these genes were also compared at the early flowering stage of the R plants corresponding to the heading stage of the S plants. Results showed the expression of PfMADS16 was lower at the seedling stage, but higher at the tillering stage in the R compared with the S plants (Figure 7B). The expression level of PfMADS16 was 7.4-fold higher in the early flowering stage of R than that of S (while S still at the heading stage), which is consistent with the expression pattern of the interacting protein PfMADS2 (Figure 7B). These results suggest that both PfMADS16 and PfMADS2 may be associated with early flowering in the R population.

Discussion

Through Arabidopsis genetic transformation, the current study found that PfMADS16 is involved in the early flowering and seed formation of P. fugax. An unexpected finding is that the PfMADS16 gene has the SVP motif and high identity to known SVP-like genes (Supplementary Figure S2A) but does not function as a normal SVP gene. When expressed in Arabidopsis, the SVP-like gene PfMADS16 promoted early flowering, which is in contrast to the results that overexpression of A. thaliana SVP led to a late-flowering phenotype (Li et al., 2008). There is a possibility of differential regulation and function of the SVP-like genes among plant species. For example, although highly similar to the PfMADS16 gene, the FPMADS16 gene has no known function in vernalization-induced flowering in F. pratensis (Ergon et al., 2013). Of the four SVP homologous genes in kiwifruit, only SVP1 and SVP3 were related to the transition to flowering, whereas the other two had distinct roles during bud dormancy (Wu et al., 2012; Voogd et al., 2015). Constitutive expression of 35S:EsSVP in Petunia W115 had little or no effect on flowering time, but clearly affected flower development (Li et al., 2016). In the current study, transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing P. fugax PfMADS16 gene showed a mild defect in floral phenotype, with choripetalous petals surrounded by four large leaf-like sepals (Figure 2A), similar to the phenotypes of transgenic Arabidopsis expressing kiwifruit SVP1 and rice OsMADS55 (Lee et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2012). In addition, like the phenotypes of transgenic Arabidopsis expressing rice OsMADS22 and OsMADS47 (Fornara et al., 2008), the PfMADS16 transgenic plants had leaf-like sepals that were retained even after fertilization (Figure 3B).

In Arabidopsis, FLC is a key gene acting at the convergence point of the vernalization and autonomous pathways and inhibits flowering by suppressing FT expression (Komiya et al., 2008). FLC and SVP form a repressor complex that suppresses the expression of both SOC1 and FT (Tao et al., 2012). However, endogenous SOC1 and FT expression were significantly increased in PfMADS16 transgenic Arabidopsis plants, and the expression of FLC was significantly decreased (Figure 6A). These results indicate that ectopic expression of PfMADS16 in Arabidopsis may regulate flowering by promoting the expression of FT and SOC1, causing co-suppression of related repressors such as FLC. The LFY expression level is an important determinant of flower initiation that negatively controls epidermal cell elongation and stomatal numbers in the pedicel (Yamaguchi et al., 2012). This is consistent with the decreased LFY expression (Figure 6A) that led to pedicel prolongation in PfMADS16 transgenic Arabidopsis plants (Figure 3A). It was noticed that PfMADS16 transgenic plants flowered earlier but had more rosette leaves than the controls under the SD condition (Table 1 and Figure 1B). Usually, the shorter the number of days prior to bolting the fewer the number of rosette leaves, although some exceptions exist (e.g., Möller-Steinbach et al., 2010). Overexpression of PfMADS16 may affect other physiological regulation mechanisms in Arabidopsis.

The most interesting finding in the current study is that the PfMADS16 gene regulates not only early flowering but also seed formation. KATANIN 1 is a microtubule severing protein, and phenotypical abnormalities in embryogenesis and seed formation of KATANIN 1 mutants can be rescued by complementation with the AtKTN1 gene (Luptovčiak et al., 2017). In PfMADS16 transgenic Arabidopsis plants, we estimated that nearly half of the pods had aborted seeds, and the expression of AtKTN1 was lower in flowers but higher in pods compared to the controls (Figure 6A). It is possible that overexpression of PfMADS16 suppresses AtKTN1 expression in flowers, causing abnormal seed setting and development in PfMADS16 transgenic Arabidopsis plants. In contrast, overexpression of PfMADS16 promotes AtKTN1 expression in pods, resulting in higher pod numbers than in controls by unknown mechanisms (Table 1). These results indicate that the PfMADS16 gene might be a flowering time promoter for efficient expression of other flowering time regulating genes, causing early flowering and seed abortion in transgenic Arabidopsis plants, as summarized in Figure 6B.

In order to understand the flowering regulation pathway of PfMADS16 in R P. fugax, we identified an interacting protein PfMADS2 with homology to L. temulentum MADS2 (LtMADS2) and L. perenne MADS2 (LpMADS2). In accordance with the present results, previous studies demonstrated that LtMADS2 transgenic Arabidopsis plants interact with the AP1 promoter, causing early flowering (Gocal et al., 2001). During vernalization the LpMADS2 gene (clustered in the AP1 subgroup) alone may be insufficient for initiating floral transition, and other genes might act together with this vernalization induced gene to initiate the floral transition (Petersen et al., 2004). In our study, the interaction protein (PfMADS2) was significantly more highly expressed in R than in S P. fugax at the tillering and flowering stages (Figure 7B), and thus we assume that PfMADS16 may act together with PfMADS2 to initiate early floral transition in R P. fugax. In addition, the phenotype of PfMADS16 transgenic Arabidopsis plants (Figure 3A) is consistent with that of LtMADS2 transgenic Arabidopsis plants that had abnormally long pedicels and ectopic flowers (Gocal et al., 2001).

Flowering time regulation is a coherent and sophisticated event, involving many genes. Based on the current experiment data, we can infer that the PfMADS16 gene is among the major genes that are involved in the early flowering regulation network in the R P. fugax population. Questions remain as to how early flowering and resulting seed abortion are associated with resistance evolution in weedy plants. Among other possibilities, herbicide stress may trigger flowering gene expression in both S and R plants, and R plants are able to survive due to the presence of resistance alleles (mutant ACCase alleles in the case of P. fugax). The early flowering trait may become inheritable due to epigenetic modification of flower genes and co-segregation with resistance traits. This hypothesis can be tested by measuring flowering gene expression after herbicide treatment and by analysis of flowering gene methylation. Indeed, PfMADS16, together with other flowering genes, was highly expressed in both R and S P. fugax plants 72 h after clodinafop-propargyl treatment at the seedling stage as compared to the untreated control in our previous study (see Figure 6A and Supplementary Table S11) (Zhou et al., 2017).

Alternatively, due to standing genetic variations in gene expression in weed populations, plants with higher expression of flowering genes by randomly co-segregate with herbicide resistance traits. Early flowering plants may escape harvest weed control strategies by early pod shedding. Weed control methods such as harvest weed seed control (HWSC) systems that have been developed to reduce weed seed return to soil during crop harvest (Walsh and Powles, 2014) may not be effective at harvesting seeds of early flowering plants (Ashworth et al., 2016). With increased knowledge on genes regulating flowering time, pod shedding and seed formation in weedy plants, it may be possible in the future to genetically manipulate these genes to reduce weed seed production, through the CRISPR-based gene drive system (Neve, 2018) for better weed control strategies.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the PfMADS16 gene, different from the normal SVP-like genes in Arabidopsis, is an early flowering regulation gene, and is associated with seed formation and viability in R P. fugax population. These results will help understand flowering regulation mechanisms in herbicide resistant weeds, and are useful for genetic-based weed control strategies aiming to manipulate the weed flowering time and reduce the soil seed bank.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

F-YZ and QY conceived and designed the experiments and wrote and revised the manuscript. F-YZ and C-CY performed the experiments. YZ and Y-JH analyzed the data. F-YZ, QY, YZ, C-CY, and Y-JH read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0201305), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31501658), and the Scientific and Technological Innovation Team for the Application and Evaluation of Pesticide Safety in Anhui Academy of Agricultural Sciences (15C1105).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.00525/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Ashworth, M. B., Walsh, M. J., Flower, K. C., Vila-Aiub, M. M., and Powles, S. B. (2016). Directional selection for flowering time leads to adaptive evolution in Raphanus raphanistrum (Wild radish). Evol. Appl. 9, 619–629. doi: 10.1111/eva.12350

Becker, A., and Theissen, G. (2003). The major clades of MADS-box genes and their role in the development and evolution of flowering plants. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 29, 464–489. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00207-0

Bravo, W., Leon, R. G., Ferrell, J. A., Mulvaney, M. J., and Wood, C. W. (2017). Differentiation of life-history traits among palmer amaranth populations (Amaranthus palmeri) and its relation to cropping systems and glyphosate sensitivity. Weed Sci. 65, 339–349. doi: 10.1017/wsc.2017.14

Carmona, M. J., Ortega, N., and Garcia-Maroto, F. (1998). Isolation and molecular characterization of a new vegative MADS-box gene from Solanum tuberosum L. Planta 207, 181–188. doi: 10.1007/s004250050471

Chen, F., Zhang, X. T., Liu, X., and Zhang, L. S. (2017). Evolutionary analysis of MIKCc-type MADS-Box genes in gymnosperms and angiosperms. Front. Plant. Sci. 8:895. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00895

Cohen, O., Borovsky, Y., David-Schwartz, R., and Paran, I. (2012). CaJOINTLESS is a MADS-box gene involved in suppression of vegetative growth in all shoot meristems in pepper. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 4947–4957. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers172

Cooke, J. E. K., Eriksson, M. E., and Junttila, O. (2012). The dynamic nature of bud dormancy in trees: environmental control and molecular mechanisms. Plant Cell. Environ. 35, 1707–1728. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02552.x

Ergon, Å, Hamland, H., and Rognli, O. A. (2013). Differential expression of VRN1 and other MADS-box genes in Festuca pratensis selections with different vernalization requirements. Biol. Plantarum. 57, 245–254. doi: 10.1007/s10535-012-0283-z

Fornara, F., Gregis, V., Pelucchi, N., Colombo, L., and Kater, M. (2008). The rice StMADS11-like genes OsMADS22 and OsMADS47 cause floral reversions in Arabidopsis without complementing the svp and agl24 mutants. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2181–2190. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern083

Gocal, G. F., King, R. W., Blundell, C. A., Schwartz, O. M., Andersen, C. H., and Weigel, D. (2001). Evolution of floral meristem identity genes. Analysis of Lolium temulentum genes related to APETALA1 and LEAFY of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 125, 1788–1801. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.4.1788

Gramzow, L., and Theissen, G. (2013). Phylogenomics of MADS-Box genes in plants—two opposing life styles in one gene family. Biology 2, 1150–1164. doi: 10.3390/biology2031150

Hartmann, U., Höhmann, S., Nettesheim, K., Wisman, E., Saedler, H., and Huijser, P. (2000). Molecular cloning of SVP: a negative regulator of the floral transition in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 21, 351–360. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x

Heap, I. M. (2020). International Survey of Herbicide-Resistant Weeds. Available online at: http://www.weedscience.org (accessed January 1, 2020).

Kaspary, T. E., Lamego, F. P., Cutti, L., de Morais Aguiar, A. C., Gonsiorkiewicz, R., Carlos, A., et al. (2017). Growth, phenology, and seed viability between glyphosate- resistant and glyphosate-susceptible hairy fleabane. Bragantia 76, 92–101. doi: 10.1590/1678-4499.542

Komiya, R., Ikegami, A., Tamaki, S., Yokoi, S., and Shimamoto, K. (2008). Hd3a and RFT1 are essential for flowering in rice. Development 135, 767–774. doi: 10.1242/dev.008631

Lee, J. H., Park, S. H., and Ahn, J. H. (2012). Functional conservation and diversification between rice OsMADS22/OsMADS55 and Arabidopsis SVP proteins. Plant Sci. 185, 97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.09.003

Li, D., Liu, C., Shen, L., Wu, Y., Chen, H., Robertson, M., et al. (2008). A repressor complex governs the integration of flowering signals in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 15, 110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.002

Li, Z., Zeng, S., Li, Y., Li, M., and Souer, E. (2016). Leaf-like sepals induced by ectopic expression of a SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE (SVP)-like MADS-box gene from the basal eudicot Epimedium sagittatum. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1461. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01461

Liu, C., Teo, Z. W. N., Bi, Y., Song, S., Xi, W., Yang, X., et al. (2013). A conserved genetic pathway determines inflorescence architecture in Arabidopsis and rice. Dev. Cell 24, 612–622. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.02.013

Luptovčiak, I., Samakovli, D., Komis, G., and Šamaj, J. (2017). KATANIN 1 is essential for embryogenesis and seed formation in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 8:728. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00728

Michaels, S. D., Ditta, G., Gustafson-Brown, C., Pelaz, S., Yanofsky, M., and Amasino, R. M. (2003). AGL24 acts as a promoter of flowering in Arabidopsis and is positively regulated by vernalization. Plant J. 33, 867–874. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01671.x

Möller-Steinbach, Y., Alexandre, C., and Hennig, L. (2010). “Flowering time control” in the plant developmental biology. Methods Mol. Biol. 655, 229–237. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-765-5_15

Mouradov, A., Cremmer, F., and Coupland, G. (2002). Control of flowering time: interacting pathways as a basis for diversity. Plant Cell 14(Suppl.), 111–130. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001362

Neve, P. (2018). Gene drive systems: do they have a place in agricultural weed management? Pest. Manag. Sci. 74, 2671–2679. doi: 10.1002/ps.5137

Petersen, K., Didion, T., Andersen, C. H., and Nielsen, K. K. (2004). MADS-box genes from perennial ryegrass differentially expressed during transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. J. Plant. Physiol. 161, 439–447. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-01212

Sentoku, N., Kato, H., Kitano, H., and Imai, R. (2005). OsMADS22, an STMADS11-like MADS-box gene of rice, is expressed in non-vegetative tissues and its ectopic expression induces spikelet meristem indeterminacy. Mol. Genet. Genom. 273, 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1093-6

Shergill, L. S., Boutsalis, P., Preston, C., and Gill, G. S. (2016). Fitness costs associated with 1781 and 2041 ACCase-mutant alleles conferring resistance to herbicides in Hordeum glaucum steud. Crop. Prot. 87, 60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2016.04.025

Smith, H. M., Ung, N., Lal, S., and Courtier, J. (2011). Specification of reproductive meristems requires the combined function of SHOOT MERISTEMLESS and floral integrators FLOWERING LOCUS T and FD during Arabidopsis inflorescence development. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 583–593. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq296

Srikanth, A., and Schmid, M. (2011). Regulation of flowering time: all roads lead to Rome. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 68, 2013–2037. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0673-y

Takeno, K. (2016). Stress-induced flowering: the third category of flowering response. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 4925–4934. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw272

Tang, W., Xu, X., Shen, G., and Chen, J. (2015). Effect of environmental factors on germination and emergence of Aryloxyphenoxy propanoate herbicide-resistant and -susceptible asia minor bluegrass (Polypogon fugax). Weed Sci. 63, 669–675. doi: 10.1614/WS-D-14-00156.1

Tang, W., Zhou, F. Y., Chen, J., and Zhou, X. G. (2014). Resistance to ACCase-inhibiting herbicides in an Asia minor bluegrass (Polypogon fugax) population in China. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 108, 16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2013.11.001

Tao, Z., Shen, L., Liu, C., Liu, L., Yan, Y., and Yu, H. (2012). Genome-wide identification of SOC1 and SVP targets during the floral transition in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 70, 549–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04919.x

VanEtten, M. L., Kuester, A., Chang, S. M., and Baucom, R. S. (2016). Fitness costs of herbicide resistance across natural populations of the common morning glory, Ipomoea purpurea. Evolution 70, 2199–2210. doi: 10.1111/evo.13016

Voogd, C., Wang, T. C., and Varkonyi-Gasic, E. (2015). Functional and expression analyses of kiwifruit SOC1-like genes suggest that they may not have a role in the transition to flowering but may affect the duration of dormancy. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 4699–4710. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv234

Walsh, M. J., and Powles, S. B. (2014). Management of herbicide resistance in wheat cropping systems: learning from the Australian experience. Pest. Manag. Sci. 70, 1324–1328. doi: 10.1002/ps.3704

Wang, T., Picard, J. C., Tian, X., and Darmency, H. (2010). A herbicide-resistant ACCase 1781 Setaria mutant shows higher fitness than wild type. Heredity 105, 394–400. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.183

Wu, R., Wang, T., McGie, T., Voogd, C., Allan, A. C., Hellens, R. P., et al. (2014). Overexpression of the kiwifruit SVP3 gene affects reproductive development and suppresses anthocyanin biosynthesis in petals, but has no effect on vegetative growth, dormancy, or flowering time. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 4985–4995. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru264

Wu, R. M., Walton, E. F., Richardson, A. C., Wood, M., Hellens, R. P., and Varkonyi- Gasic, E. (2012). Conservation and divergence of four kiwifruit SVP-like MADS-box genes suggest distinct roles in kiwifruit bud dormancy and flowering. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 797–807. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err304

Yamaguchi, N., Yamaguchi, Ayako, Abe, M., Wagner, D., and Komeda, Y. (2012). LEAFY controls Arabidopsis pedicel length and orientation by affecting adaxial–abaxial cell fate. Plant J. 69, 844–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2011.04836.x

Zhou, F., Zhang, Y., Tang, W., Wang, M., and Gao, T. (2017). Transcriptomics analysis of the flowering regulatory genes involved in the herbicide resistance of Asia minor bluegrass (Polypogon fugax). BMC Genomics 18:953. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4324-z

Keywords: Polypogon fugax, herbicide resistance, flowering regulation, MADS family, Arabidopsis thaliana

Citation: Zhou F-Y, Yu Q, Zhang Y, Yao C-C and Han Y-J (2020) StMADS11 Subfamily Gene PfMADS16 From Polypogon fugax Regulates Early Flowering and Seed Development. Front. Plant Sci. 11:525. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00525

Received: 25 January 2020; Accepted: 07 April 2020;

Published: 08 May 2020.

Edited by:

Akira Kanno, Tohoku University, JapanCopyright © 2020 Zhou, Yu, Zhang, Yao and Han. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Feng-Yan Zhou, emJzemhvdWZ5QDE2My5jb20=

Feng-Yan Zhou

Feng-Yan Zhou Qin Yu

Qin Yu Yong Zhang1

Yong Zhang1