- 1Department of Education and Social Policy, University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, Greece

- 2Department of English Language and Literature, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

- 3Department of Special Pedagogy, The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland

- 4Department of Special and Rehabilitation Education, Faculty of Education, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia

- 5Heidelberg University of Education, Heidelberg, Germany

This mixed-methods study explores the relationship between internal motivation and learning environment support in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classrooms among students with diverse learning needs across four European contexts. Ninety-five students with visual, hearing, mobility impairments, or specific learning difficulties participated. Drawing on quantitative data from the Foreign Language Enjoyment Scale and qualitative interviews, the study examines how teacher support, peer collaboration, and technological tools shape learners’ experiences. While both teacher and peer support significantly predict internal motivation, the strength and nature of this relationship vary depending on the type of learning need. In particular, teacher support was most influential for students with visual impairments and learning difficulties, while peer support played a greater role for students with hearing and mobility support needs. Notably, students’ motivation often appeared to be independent of classroom-based support, with family encouragement emerging as a key informal driver. The study also identifies critical gaps in assistive technology training and access, with many students reporting limited instruction and inconsistent technical support. Students emphasized the need for accessible digital materials, flexible assessment strategies, and better-prepared teachers. Qualitative findings highlight preferences for structured environments, multimodal learning, and varied collaboration formats—individual, pair, or group—depending on students’ specific support needs and classroom contexts. These results point to the need for targeted teacher education, inclusive pedagogical design, and sustained systemic efforts to ensure equity in language learning for students with diverse profiles.

1 Introduction

Recent years have witnessed a growing emphasis on inclusive education, particularly in foreign language learning environments where students with diverse learning needs face unique challenges. We use the term “students with diverse learning needs” rather than “students with disabilities” to recognize that each learner brings unique strengths to the language learning process. As defined by Chilla et al. (2024, p. 6), diverse learning needs encompass “various backgrounds, developmental stages, skills and abilities, identities, and general physiological and psychological features of learners that might affect the current learning process or hinder the accessibility of content.” While Universal Design for Learning [UDL, Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST), 2024] principles have emerged as a promising framework for creating inclusive classrooms, significant gaps remain in understanding how different support systems influence students’ language learning experiences. Despite these documented benefits, access to quality foreign language instruction is frequently limited for students with diverse learning needs (Sparks, 2016). This cross-national European study examines the complex interplay between Learning Environment Support and internal motivation among students with diverse learning needs in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classrooms. Drawing from data collected across Greece, Germany, Slovenia, and Poland, the research investigates how teacher support, peer collaboration, and technological tools shape the learning experiences of students with visual impairments, hearing impairments, physical disabilities, and specific learning difficulties. Through a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative analysis of Foreign Language Enjoyment Scale data with qualitative interviews, the study explores the effectiveness of current support systems and identifies areas for improvement in inclusive language education. Particular attention is paid to the role of Digital Technology (DT) tools, assessment strategies, and collaborative learning approaches in supporting these students’ language acquisition journey. This study adopts the term “Digital Technology” (DT) rather than “Information and Communication Technology” (ICT) to reflect the broader scope of technologies utilized in inclusive language education. While ICT has been widely used in previous literature, DT better encompasses the full spectrum of digital tools, platforms, and environments that support diverse learning needs, including assistive technologies, learning applications, and virtual environments. The findings reveal both the resilience of students with diverse learning needs and the critical importance of creating supportive learning environments that can effectively harness their internal motivation. By examining these factors across different European educational contexts, this research contributes valuable insights for educators, policymakers, and researchers working to enhance inclusive language education practices.

This study, conducted as part of the SPLENDID project (Supporting Foreign Language Learning for Students with Disabilities1) funded by the Hellenic State Scholarships Foundation IKY of the Erasmus + program, aims to address these gaps by investigating the foreign language learning experiences of students with diverse needs across four European countries. The project, led by the University of Macedonia, brings together nine partners, including five universities: the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Pädagogische Hochschule Heidelberg PHHD (Heidelberg University of Education), the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin in Poland, and the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia.

2 Literature review

Recent research trends demonstrate a surge in scholarly attention toward inclusive pedagogical approaches, particularly since 2010 (Stentiford and Koutsouris, 2021). Modern educational frameworks have evolved beyond traditional differentiation models, embracing an approach that recognizes and values the inherent diversity of student learning profiles (Florian, 2015). This shift holds particular significance for language education, where diverse learning needs intersect with the complexities of second language acquisition.

The Universal Design for Learning [UDL, Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST), 2024] framework has emerged as a critical approach in educational settings. UDL emphasizes the need to create inclusive learning environments that accommodate diverse learning preferences and needs, thereby reducing barriers to education for all students, including those with disabilities (Black et al., 2015; Rao et al., 2014; Chavarría et al., 2023). One of the foundational aspects of UDL is its focus on flexibility and adaptability in teaching methods. Research indicates that UDL principles can significantly enhance the learning experiences of students with disabilities by providing multiple means of engagement, representation, and action/expression (Rao et al., 2015; Chavarría et al., 2023). Studies have shown that incorporating UDL into foreign language curricula not only supports students with disabilities but also enhances the overall learning environment for all students (Rivera, 2019). For example, Borzova and Shemanaeva (2020) highlighted the effectiveness of multifunctional tasks in foreign language education, which can be designed to cater to various learning styles and needs, thereby promoting inclusivity. This adaptability is further enhanced through the integration of technology and blended learning approaches, as demonstrated by Klimova et al. (2018) who found that diverse digital resources and learning modalities can effectively engage students with diverse learning preferences and needs. While the benefits of UDL are frequently highlighted, it is important to acknowledge critical perspectives on its limitations and implementation. Few would argue that designing a curriculum with inclusion in mind is a harmful pedagogical approach. UDL has certainly “opened a door” (Baglieri, 2020) for academics to upskill in their consideration of accessibility and inclusion. Further, student and teacher satisfaction with UDL are frequently reported to be high (e.g., Cumming and Rose, 2022). However, given the lack of evidence for effectiveness, it is important to critically reflect on the value of UDL. In particular, Creaven (2025) argues that the erasure of disability in UDL documentation, and the inability of UDL nor any instructional design approach to overcome the challenges of the built environment, requires contemplation. As Creaven (2025) argues, UDL’s emphasis on “all learners” while avoiding specific reference to disability can inadvertently marginalize students with extensive support needs by limiting opportunities to address their specific needs. Additionally, Creaven (2025) contends that UDL’s focus on instructional design may distract from addressing more fundamental barriers in the physical and sensory environment that significantly impact students with diverse learning needs. Furthermore, research also reveals a significant implementation gap, as many educators lack the necessary training to effectively apply UDL principles in their teaching practices (Moriña and Perera, 2018). Toyama and Yamazaki (2021) highlight the barriers that insufficient faculty training presents, indicating that educators often struggle to implement UDL principles effectively, which can negatively impact learning outcomes for students with disabilities. Diaz-Vega et al. (2020) specifically noted that insufficient knowledge and implementation of Universal Design principles among university professors creates potential barriers for students with disabilities, highlighting the critical need for enhanced faculty development in inclusive educational practices. The implementation of UDL principles is closely tied to understanding the relationship between internal motivation and external support systems in language learning. Students with a high degree of internal motivation are more likely to engage in self-directed learning and persist in their language studies (Pan and Chen, 2021; Schwartzman and Boger, 2017). For instance, Pan and Chen (2021) found that perceived usefulness and ease of use of technology, alongside teacher support, positively impacted students’ self-directed language learning, particularly when accommodations align with individual learning needs. Based on the work of Eichhorn et al. (2019), applying UDL principles enables educators to create inclusive classrooms that acknowledge the diverse needs of English Learners (ELs), thereby enhancing engagement and learning outcomes for all students. External support systems are vital in fostering and sustaining internal motivation, especially for students with diverse learning needs; Teacher support has been shown to have a direct impact on students’ motivation levels, with particular importance for learners with disabilities who may require additional scaffolding (Piticari, 2023). Teachers who provide encouragement, constructive feedback, and accessible resources can significantly enhance students’ self-efficacy and motivation (Lai, 2015; Piticari, 2023). Huang (2023) highlighted the importance of peer support in online language learning environments, noting that positive interactions among peers can enhance self-efficacy and mitigate negative emotions associated with language learning, which is particularly relevant for students who may face additional challenges due to their diverse learning needs. Educational technology can improve learners’ self-efficacy and facilitate a more interactive and accessible learning experience (Zhang, 2022). Zheng and Zhou (2022) noted that cooperative online learning environments could enhance foreign language enjoyment while providing necessary accommodations for different learning needs. This indicates that when learners have access to supportive technological tools that align with UDL principles, their internal motivation can be further amplified, leading to improved language acquisition (Allen et al., 2018).

Self-Determination Theory (SDT), developed by Deci and Ryan (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Ryan and Deci, 2000), provides a comprehensive framework for understanding motivation in educational contexts, including language learning. SDT posits that optimal learning occurs when three fundamental psychological needs are met: autonomy (experiencing choice and volition), competence (feeling effective), and relatedness (feeling connected to others). Alrabai (2021) conducted a controlled longitudinal study demonstrating that autonomy-supportive teaching significantly enhanced learner autonomy in English language classrooms. His findings revealed that perceived choice emerged as the strongest predictor of learner autonomy, followed by perceived competence, teacher autonomy support, and intrinsic motivation. While Alrabai’s research involved general EFL populations rather than students with diverse learning needs, the principles of SDT are particularly relevant to our study population. For students with diverse learning needs, the mechanisms through which autonomy and motivation develop may be even more complex, with family support potentially playing a crucial mediating role. Wehmeyer (2023) specifically examined SDT applications for learners with disabilities, emphasizing that when these students are encouraged to take control of their learning processes, their intrinsic motivation and subsequent learning outcomes improve substantially. Similarly, Haakma et al. (2017) demonstrate that need-supportive environments enhance motivation for students with congenital disabilities by addressing their basic psychological needs.

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (EST) (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986) provides a valuable lens through which to understand the complex interplay of environmental factors affecting students’ language learning motivation. This theory conceptualizes development as occurring within nested environmental systems, from the immediate microsystem (family, classroom) to broader macrosystems (cultural attitudes, educational policies). As Nolan and Owen (2024) note, EST can be used to examine single factors, groups of factors or whole systems as well as the relationships therein. Neal and Neal (2013) offer an important reconceptualization of this theory, proposing that ecological systems should be viewed not as nested, but as “networked”—an overlapping arrangement of structures connected through social interactions. This networked perspective has particular relevance for language education, where “context” has become increasingly recognized as essential to second language acquisition (Chong et al., 2023). As Liaqat et al. (2025) demonstrate, the ecological environment in language learning settings involves multiple interconnected systems. Their research shows significant correlations between family connection and factors such as self-esteem and problem-solving, while finding that teacher support and peer support are significant direct predictors of academic resilience. Their analysis of these relationships within Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework illustrates how different microsystems contribute to students’ resilience in language learning, with each system playing distinct yet complementary roles in supporting students’ motivation and academic achievement. Lansey et al. (2023) apply the EST framework specifically to educational decision-making, demonstrating how the macrosystem—including institutional patterns, cultural beliefs, and both explicit and implicit ideologies—profoundly shapes how education teams perceive students with diverse needs and the services they require. Their research reveals that placement decisions often reflect these systemic influences rather than individual student needs.

Research into the psychological aspects of language acquisition reveals the intricate relationship between emotional wellbeing and learning outcomes. Domagała-Zyśk (2024), for example, emphasizes how affective factors shape the language learning experience (Domagała-Zyśk, 2024), building upon foundational theories about emotional barriers in language acquisition (Krashen, 1985). Modern scholarship has shifted toward examining success factors, with researchers documenting connections between emotional engagement and language learning achievement. Studies reveal that students experiencing positive emotions demonstrate enhanced learning outcomes (Liu and Wang, 2021), stronger classroom participation (Pekrun et al., 2007), and increased target language communication (Khajavy et al., 2018). This aligns with broader positive psychology frameworks that emphasize the role of emotional engagement, interpersonal connections, and achievement recognition in educational success (Seligman, 2018).

While the negative emotional factors like Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety (Horwitz et al., 1986) have been investigated for a longer time now, the positive concept of Foreign Language Enjoyment is more recent. Investigations by Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014) 2016 highlight how positive classroom experiences enhance language learning effectiveness. Their research identifies three key elements that contribute to successful language acquisition: supportive learning environments, student attitudes, and relationship dynamics between learners and educators. These findings gain additional significance when considering students with diverse learning needs.

The intersection of sensory impairments and language learning presents unique considerations. Research indicates that sensory limitations can affect relationship formation patterns crucial for language development (Rødbroe and Janssen, 2006). Studies emphasize the importance of student agency in educational decisions, noting its particular relevance for maintaining engagement among at-risk learners (Down and Choules, 2017). Supportive student-teacher relationships emerge as a crucial factor, with research demonstrating their impact on learning motivation (Clark, 2000; Deci et al., 1991).

Visual impairments create distinct challenges in language acquisition, particularly regarding incidental learning opportunities typically available through observation (Corn and Erin, 2010; D’Andrea and Siu, 2015). For deaf and hard of hearing students, language learning involves unique obstacles while offering paths for academic growth (Domagała-Zyśk et al., 2021). Current research explores various aspects of their language development, including written communication skills and comprehension strategies (Domagała-Zyśk and Podlewska, 2024, Chomicz, 2025), reading comprehension skills (Sedláčková, 2016), EFL listening (Domagała-Zyśk and Podlewska, 2024) and speaking competences (Domagała-Zyśk and Podlewska, 2019, Domagała-Zyśk, 2021). Research does not only tackle the issues of removing the obstacles and barriers in EFL learning, but also enhancing learner autonomy (Sedlackova and Tothova, 2022), fostering motivation (Kontra and Csizer, 2020) or enhancing and measuring learning enjoyment in EFL for deaf and hard of hearing students (Domagała-Zyśk, 2024).

Learning disabilities introduce additional complexity to foreign language instruction. Conditions like dyslexia affect both native and foreign language processing, necessitating specialized instructional approaches (Nijakowska, 2019). Studies by Kormos (2017a),b and Nijakowska (2020) document varying impacts on language literacy development. Languages with complex spelling patterns, such as English, present particular challenges (Reid, 2016; Nijakowska, 2010). However, evidence suggests that appropriate educational adaptations enable successful language learning for most students with dyslexia (Nijakowska et al., 2016).

Students with physical disabilities exhibit diverse language learning capabilities. Their performance spans the full spectrum of academic ability (Boenisch, 2016). While many demonstrate strong communication skills, some require additional support with learning structure and information processing (Bergeest et al., 2019). These findings emphasize the importance of tailored support systems that acknowledge individual learning profiles while maintaining high academic expectations.

These three theoretical frameworks—Universal Design for Learning (UDL), Self-Determination Theory (SDT), and Ecological Systems Theory (EST)—provide complementary lenses through which to examine the complex interplay between internal motivation and external support systems for language learners with diverse needs. While UDL focuses on how educational environments can be designed to accommodate diverse learning profiles through multiple means of engagement, representation, and action/expression (Rao et al., 2015), SDT explains the psychological mechanisms through which such adaptations foster motivation by satisfying needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan and Deci, 2000). EST extends this understanding by contextualizing these processes within interconnected environmental systems, from immediate classroom interactions to broader cultural and institutional frameworks (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). This integrated theoretical perspective suggests that students’ internal motivation for language learning emerges from a complex ecosystem of support, where teacher practices (informed by UDL), psychological need satisfaction (as described by SDT), and multiple environmental layers (outlined by EST) interact in ways that have yet to be fully understood. Despite the theoretical richness of these frameworks, research examining how these elements interact specifically for students with diverse learning needs in foreign language contexts remains limited. In particular, the relative importance of different environmental systems—teachers, peers, family, and institutional structures—in supporting internal motivation for language learning has not been systematically investigated across different types of learning needs and national educational contexts. This gap underscores the need for a mixed-methods, cross-national approach that can capture both the patterns of relationship between environmental support and internal motivation (RQ1), their manifestation across different educational contexts (RQ2), and the influence of specific educational factors on these relationships (RQ3).

3 Methodology

This exploratory mixed-methods study adopted a cross-national perspective to examine the foreign language learning experiences of students with diverse learning needs. Recognizing existing research gaps and the necessity for a deeper understanding in this area, the study aimed to address the following research questions:

RQ1a: How does Learning Environment Support (teacher and peer support) influence students’ internal motivation in language learning?

RQ1b: Which aspects have the strongest predictive power?

RQ2a: How do levels of Learning Environment Support and internal motivation compare across the four European countries?

RQ2b: How do these patterns differ among students with diverse learning needs?

RQ3: To what extent do educational factors (length of language study, school type, and language proficiency level) influence internal motivation and environmental factors among students with diverse learning needs who learn EFL?

3.1 Ethical considerations

The research project adhered to the respective regulations in Greece, Germany, Slovenia, and Poland, following each country’s institutional and national guidelines for studies involving vulnerable groups. Strict ethical protocols were implemented to safeguard participant confidentiality and maintain data integrity. To ensure anonymity, student names were substituted with numerical identifiers during both data collection and analysis, and any identifying information was omitted from interview transcripts. Written parental consent was obtained for all participants, along with the students’ assent. To verify the authenticity of interview data, all sessions were audio-recorded with consent and transcribed verbatim, with translations cross-checked by bilingual researchers from each participating nation. Standardized interview protocols were employed across all four countries to maintain consistency in data collection.

3.2 Sample characteristics

The study comprised 95 participants across four European countries: Greece (n = 16), Germany (n = 24), Slovenia (n = 23), and Poland (n = 32). While the primary target age range was 8–18 years to focus on primary and secondary education, the sample included seven Slovenian secondary students aged 18–25 with visual impairments, deaf/hard of hearing, learning difficulties, and mobility impairments. This inclusion aligned with established special education frameworks that recognize extended educational trajectories for students with disabilities, particularly in secondary settings where an individualized learning pace takes precedence over standardized age progression.

Participants represented four main categories of diverse learning needs: visual impairment (n = 16), Deafness/Hard of Hearing (n = 14), physical/motor impairment (n = 32), and specific learning difficulties (n = 33). The study adopted a broad conceptualization of specific learning difficulties (SpLD) as an umbrella term. While SpLD traditionally encompasses conditions such as dyslexia, dyspraxia/DCD, dyscalculia, and ADHD, we included six Polish students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in this category for analytical purposes. This grouping is supported by research evidence, including Foti et al.’s (2015) meta-analysis of 11 studies demonstrating similar implicit learning patterns between individuals with ASD and those with other learning differences. Additionally, this classification aligns with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act’s (IDEA) definition of specific learning disabilities as “a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language” (US Department of Education, 2019, para 1).

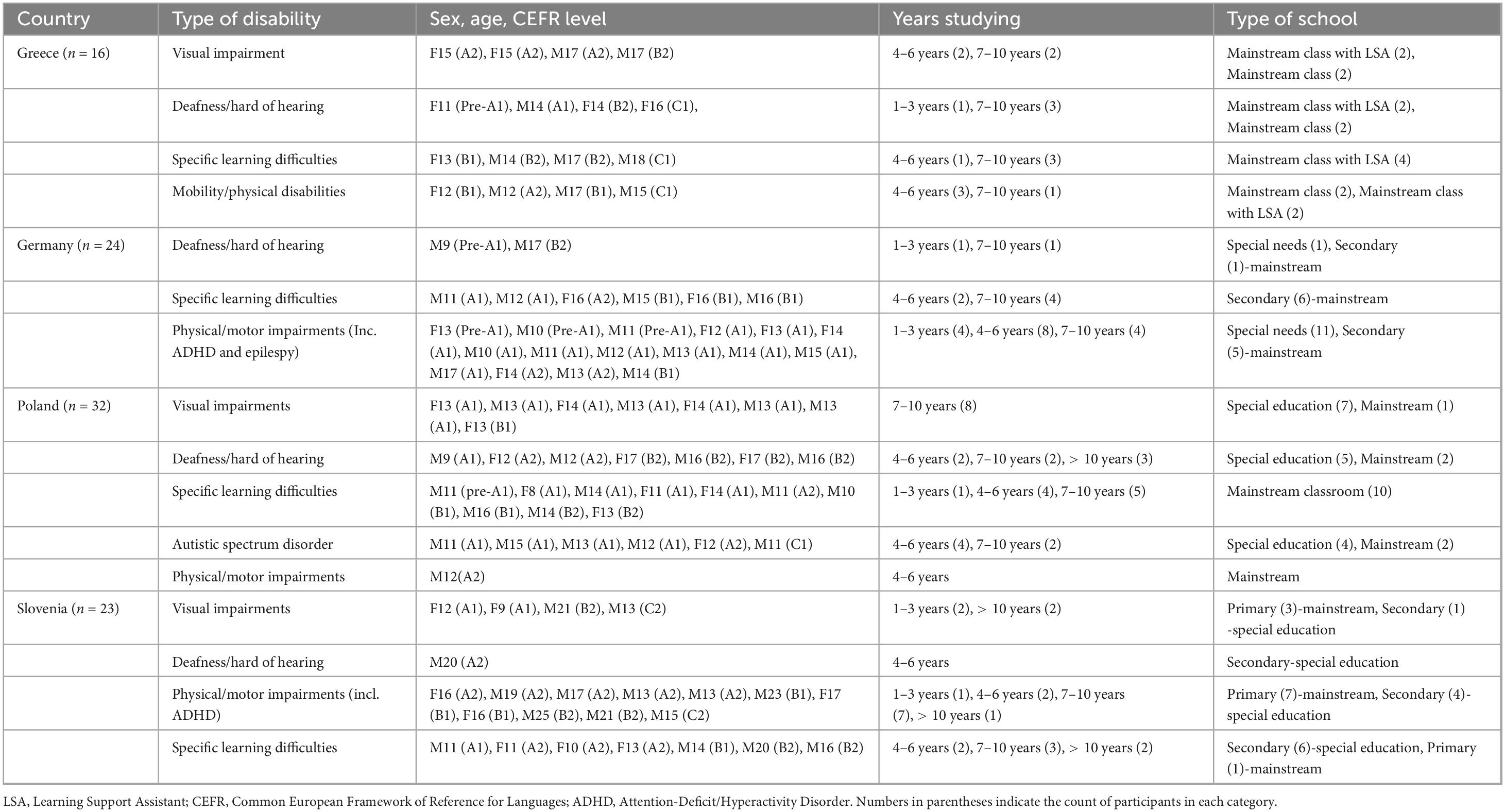

The sampling strategy employed context-specific methods in each country to ensure representation of students with diverse learning needs. Inclusion criteria required participants to: (1) have an official diagnosis of disability from their respective national authorities, (2) be actively learning at least one foreign language, and (3) be enrolled in primary or secondary education in either mainstream or special education settings. While the study was open to students learning any foreign language, all participants were studying English, with some additionally pursuing other languages such as German or French. Students’ linguistic performance was indicated using CEFR (Common European Framework of Reference for Languages) levels, which were most commonly reported jointly by teachers and students, or by parents and students. In a small number of cases (3), researchers estimated the CEFR level based on contextual indicators such as coursebooks in use, years of language study, and observed language use during the interview. These CEFR levels were used as an approximate indicator of English language proficiency for analytical purposes. Table 1 presents the profile of students with diverse needs who participated in the study.

3.3 Data collection and analysis

Data collection comprised semi-structured interviews lasting between 30 and 60 min, designed to gather both qualitative and quantitative information about participants’ language learning contexts and proficiency levels. Students’ experiences were evaluated using items from the Foreign Language Enjoyment Scale (Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2014), with responses recorded on a 5-point Likert scale. The qualitative analysis focused on the following questions:

Q1. DT Tools: Usage, Recommendations, and Support:

a. Is there any specific support you would like to have? What tools do you use?

b. Would you recommend them (why/why not)?

c. Is there a particular tool that helps you in developing speaking/listening/writing/reading skills?

d Do you get any support using these tools?

Q2. Material formats, assessment strategies, and teacher support:

a. How do you prefer to receive instructional materials and assignments in your foreign language classes?

b. Do you have any specific needs when it comes to language assessment (tests, etc.)? What would you recommend your teacher should do to support you?

c. What does your teacher do that supports your learning with digital learning needs (DLN)?

d. Can you refer to a time where your language teacher motivated you in learning English (e.g., they proposed that you should participate in a contest, engaged you in a debate, organized an innovative activity, etc.)?

e. Is there anything you would like your teacher to do to support your language learning?

Q3. Student perspectives on group work and peer collaboration:

a. How would you describe working with your classmates?

b. How do you like working best (on your own, in pairs, in groups) and why?

Q4. Internal Motivation: Enjoyment, Challenges, and Support Systems

Internal motivation was explored through four open-ended questions addressing both positive and challenging aspects of language learning, as well as future goals and additional reflections. The first two questions were part of the original interview protocol and were deductively analyzed. The final two questions were more open-ended and analyzed inductively to capture emerging themes, particularly around family encouragement and learner aspirations.

a. What do you enjoy about learning a foreign language? Is there an activity you really like?

b. What makes it (sometimes) hard/difficult for you to learn the language(s)? Can you tell me a situation during which you had a problem? Were you able to solve the problem?

c. What are your plans for learning and using languages in the future?

d. Is there something else that you wish to add concerning your language learning pathway?

Together, these four questions provided insights into emotional engagement, perceived competence, learner resilience, and the motivational role of family support. This thematic block aligns closely with SDT—particularly the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness—and EST by situating learners’ motivation within family, school, and broader sociocultural contexts.

3.3.1 Quantitative analysis

For this study, we constructed three distinct variables from the questionnaire items to examine different aspects of the foreign language learning experience: Internal Motivation (IM), Learning Environment Support—Teacher (LES-T), and Learning Environment Support—Peer (LES-P).

The Internal Motivation (IM) variable was constructed using nine items from the Foreign Language Enjoyment Inventory (Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2014) that capture students’ personal engagement, emotional connection, and achievement in language learning: “I can be creative in my English classroom,” “I don’t get bored,” “I enjoy learning English/foreign languages,” “I feel as though I’m a different person,” “I’m a worthy member of my English class,” “I’ve learnt interesting things,” “In my English class I feel proud of my accomplishments,” “It’s cool to know English,” and “Making errors is part of the learning process.” These items were selected to reflect various aspects of internal motivation, including creativity, engagement, enjoyment, identity, self-worth, learning value, pride, positive attitude, and growth mindset.

The Learning Environment Support—Teacher (LES-T) variable was formed using three items that specifically address teacher-related support factors: “The teacher is encouraging,” “The teacher is friendly,” and “The teacher is supportive.” These items were chosen to capture the essential aspects of teacher support in creating a positive learning environment for students with diverse needs.

The Learning Environment Support—Peer (LES-P) variable comprised eight items focusing on peer interaction and classroom atmosphere: “I can laugh off embarrassing English mistakes,” “It’s a positive environment,” “The peers are nice,” “There is a good atmosphere,” “We form a tight group,” “We have common “legends,”” “We laugh a lot,” and “English classes—it’s fun.” These items were selected to reflect the social and emotional aspects of peer support in language learning.

The reliability analysis supported this three-construct approach, with all scales showing acceptable to good internal consistency (IM: α = 0.800; LES-T: α = 0.880; LES-P: α = 0.766).

Descriptive statistics were computed for each variable. Pearson correlations were used to examine associations between Internal Motivation, Teacher Support, and Peer Support as a preliminary step to regression. Subsequently, multiple regression analyses were conducted to identify the extent to which teacher and peer support predicted students’ internal motivation, both across the full sample and within specific types of diverse learning needs. Additionally, Kruskal-Wallis tests were employed to explore potential differences in support and motivation scores across countries, types of diverse learning needs, and educational variables (e.g., CEFR level, school type), offering a non-parametric approach appropriate for small and uneven group distributions.

3.3.2 Qualitative analysis

The qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews with students and analyzed using thematic analysis, following the three-phase model of qualitative content analysis proposed by Elo et al. (2014): preparation, organization, and reporting. In the preparation phase, responses to ten open-ended questions were read repeatedly to ensure familiarity and comprehensive inclusion. These responses were then grouped into four thematic areas aligned with the study’s integrated theoretical framework (UDL, SDT, EST):

(Q1) digital tools and assistive technology,

(Q2) instructional materials, assessment, and teacher support,

(Q3) peer interaction, and

(Q4) internal motivation and support systems.

In the organization phase, a deductive coding structure was applied to the responses of eight predefined questions, corresponding to the first three themes (Q1–Q3) and the first part of the fourth theme (Q4a–b, related to enjoyment and learning challenges). An inductive coding approach was used for the final two open-ended prompts—Q4c and Q4d—to capture emergent motivational patterns, particularly the role of family support in shaping learners’ aspirations and emotional engagement. In the reporting phase, selected student quotes were used to illustrate key themes and subthemes, with demographic markers (age, CEFR level, support need, country) included to support cross-case comparisons. This combined deductive–inductive strategy allowed for a nuanced understanding of how internal motivation is situated within both personal and ecological contexts.

4 Results

4.1 Influence of learning environment (RQ1)

4.1.1 Analysis 1: descriptive patterns of support and motivation

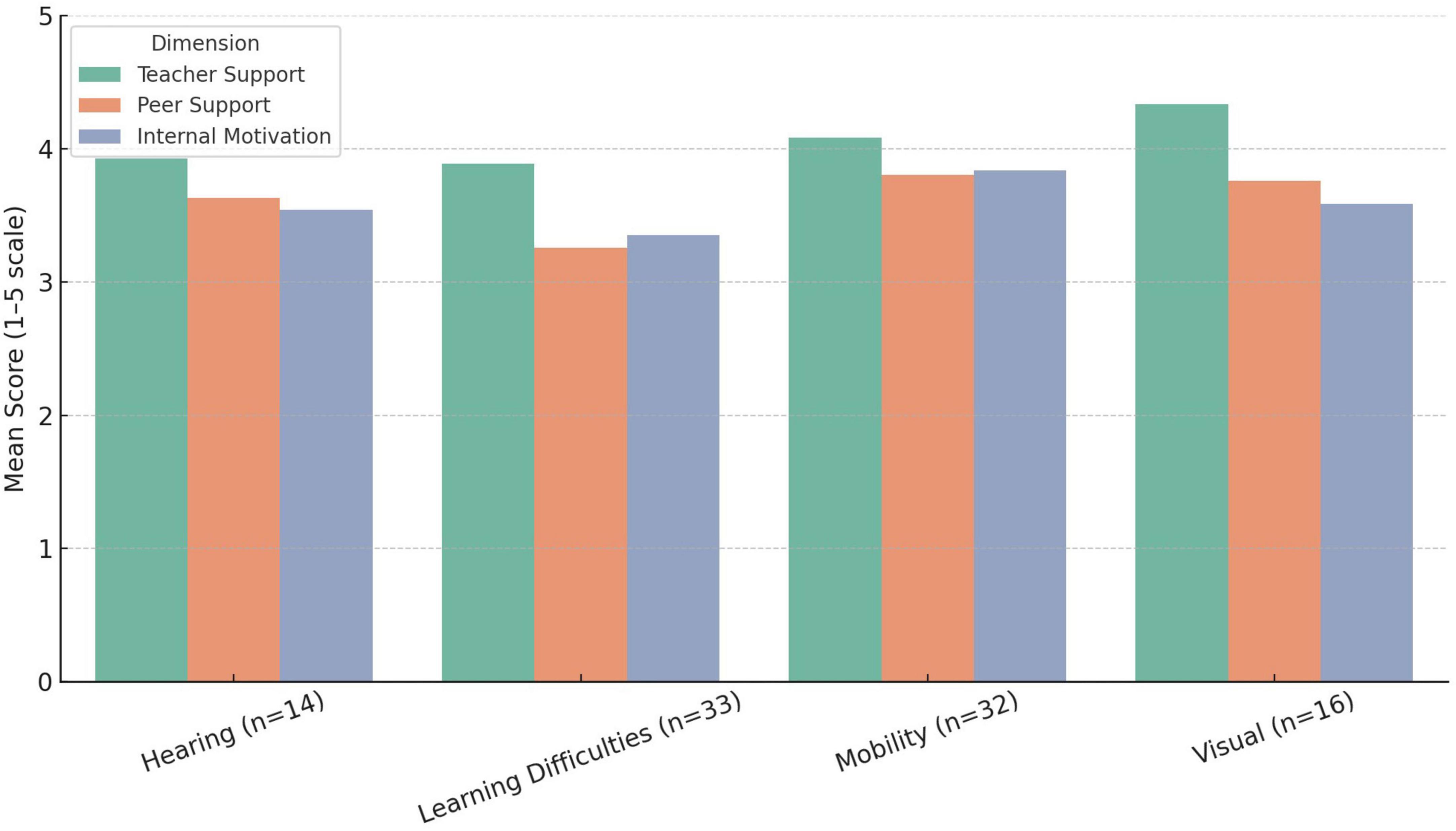

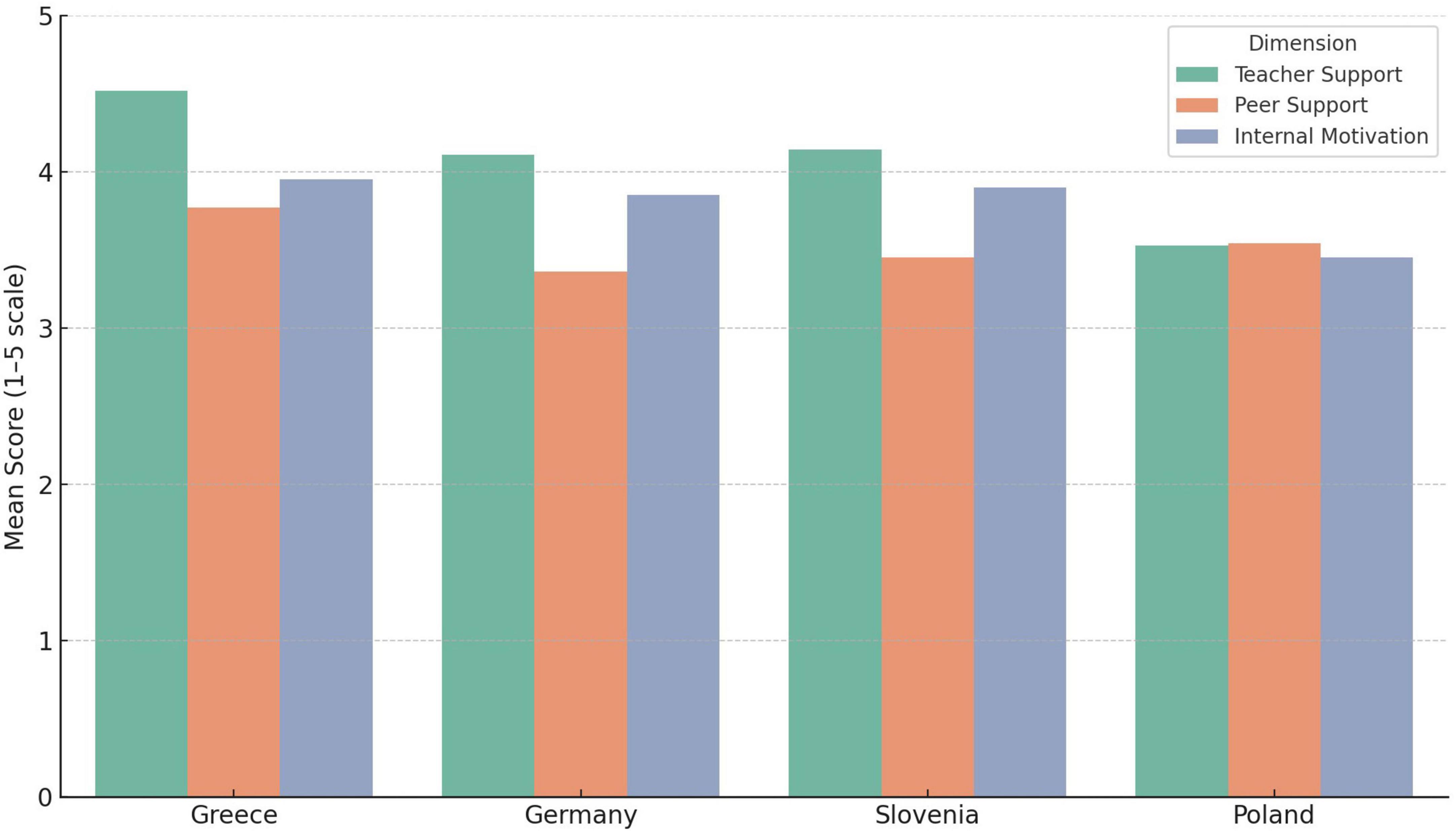

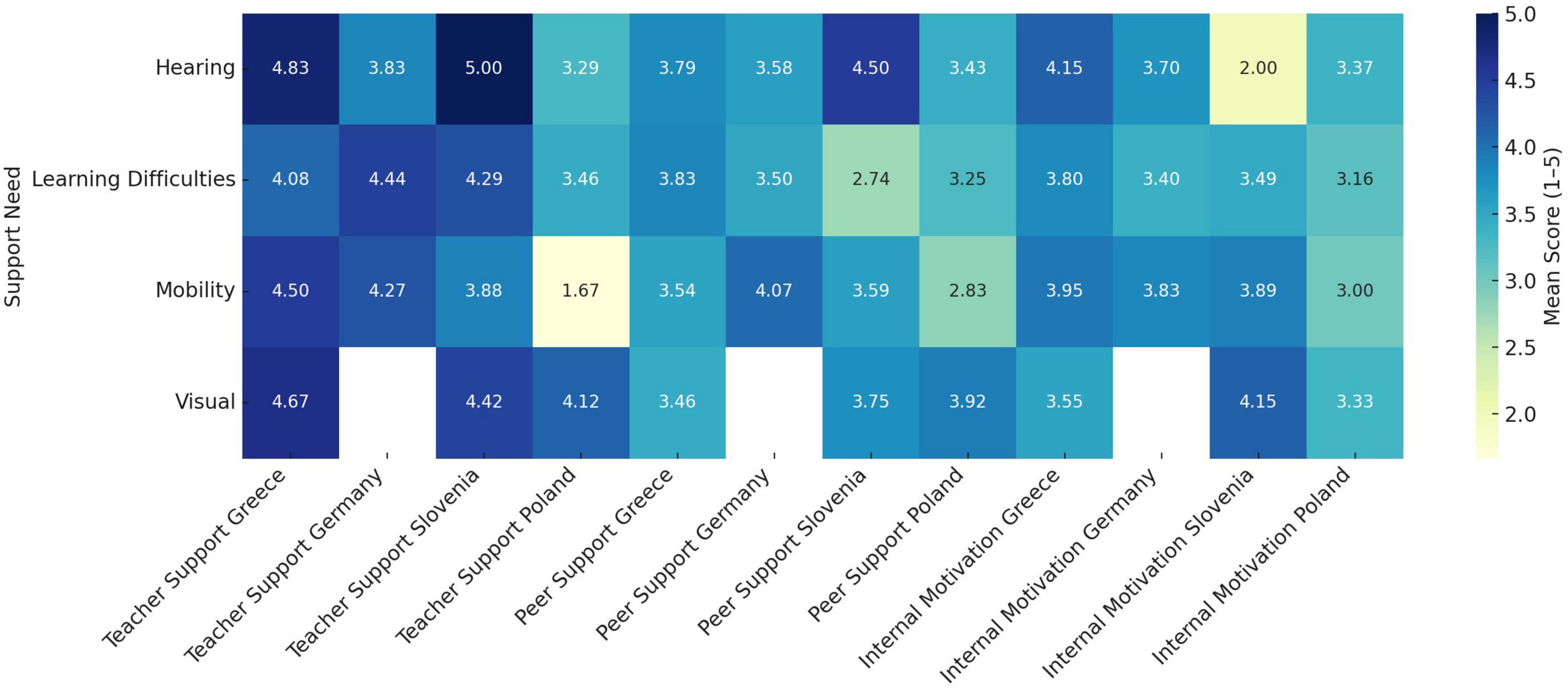

Figure 1 examines three distinct dependent variables (Teacher Support, Peer Support, and Internal Motivation) independently across four types of support needs. For Teacher Support, students with visual support needs report the highest levels (4.33), followed by those with mobility support needs (4.09), while students with hearing support needs (3.85) and learning difficulties (3.79) report lower levels. In terms of Peer Support, students with visual support needs again report the highest levels (3.85), while those with mobility (3.57) and hearing support needs (3.53) report moderate levels. Students with learning difficulties report notably lower peer support (3.28), which might indicate different dynamics in peer relationships for this group or greater self-sufficiency making them not to look for outside support.

Interestingly, the pattern shifts when examining Internal Motivation. Here, students with mobility support needs show the highest levels (3.94), followed by those with visual support needs (3.82) and hearing support needs (3.74), while students with learning difficulties report the lowest levels (3.50). This variation is particularly noteworthy because it shows that high levels of support don’t necessarily correspond directly to high levels of motivation. For instance, while students with visual support needs report the highest levels of both teacher and peer support, they don’t show the highest internal motivation. This suggests that the relationship between support and motivation might be more complex than a simple direct correlation.

Furthermore, the consistently higher Teacher Support scores across all groups compared to Peer Support could indicate several important systemic factors: teachers may be more attuned to providing support for students with different support needs; schools might have better-established systems for teacher support compared to peer support mechanisms; students might have more structured interactions with teachers than with peers; and teachers might receive specific training for working with students with different support needs. These findings highlight the institutional strengths in teacher support while also identifying potential areas for improvement in raising self-awareness of peers to support better their counterparts who face more challenges in the learning process.

4.1.2 Analysis 2: multivariate regression analysis by support need

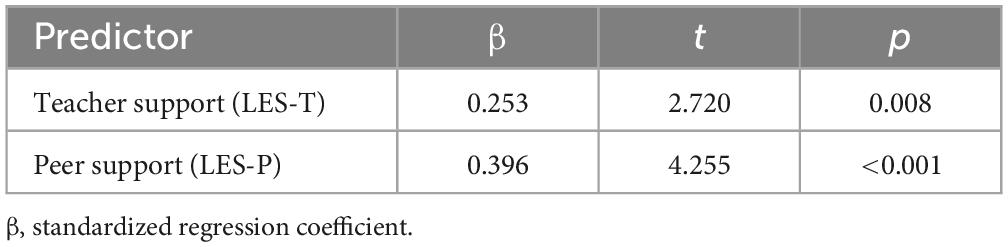

To examine how Learning Environment Support influences students’ internal motivation (RQ1), we first conducted a multivariate regression analysis using the full sample (Table 2).

Our analysis revealed that both teacher support (β = 0.25, p < 0.01) and peer support (β = 0.40, p < 0.001) significantly predicted internal motivation, with peer support demonstrating a stronger effect. Together, these support variables explained 28.1% of the variance in internal motivation across the full sample [R2 = 0.281, F(2, 92) = 17.99, p < 0.001].

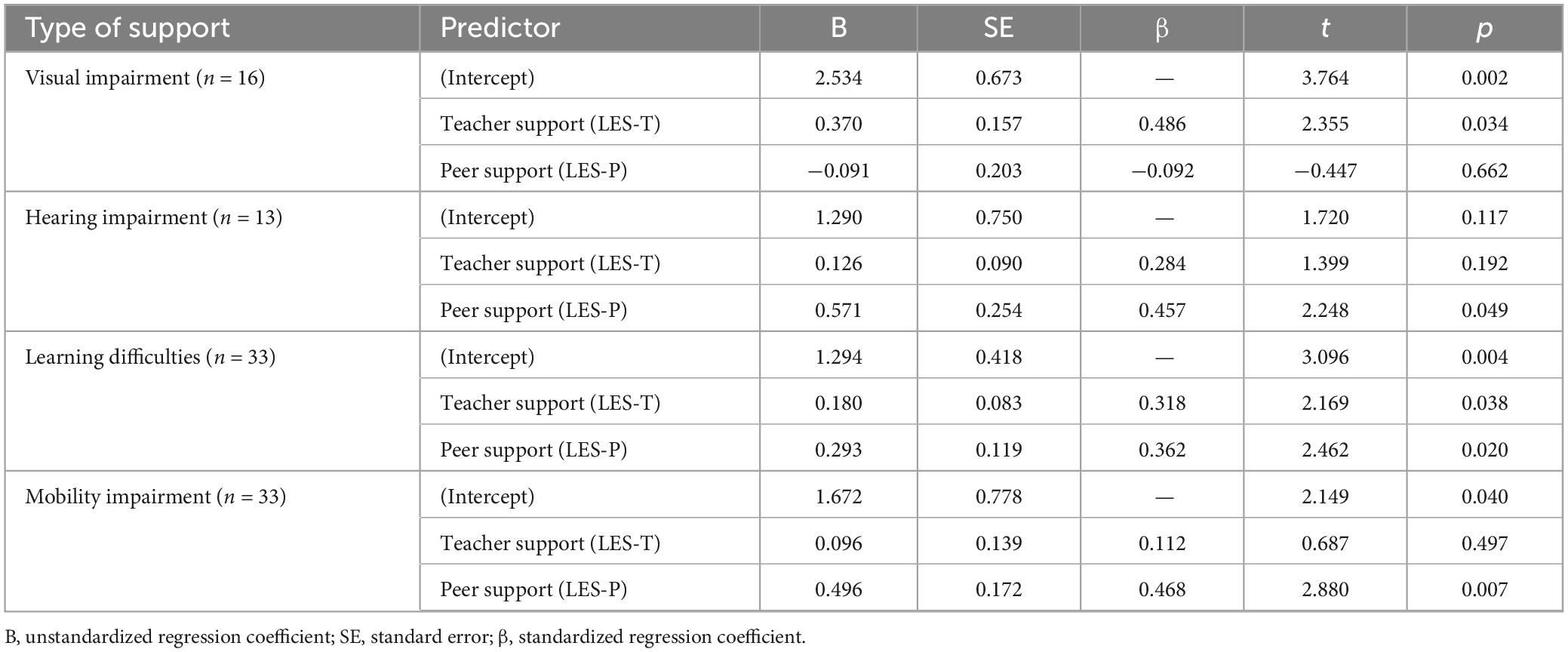

To better understand these relationships, we conducted multivariate regression analyses for each support needs as presented in Table 3. These models revealed distinct patterns in how different forms of support predict internal motivation across groups. As shown in Table 3, students with visual support needs demonstrated a significant positive relationship between teacher support and motivation (β = 0.486, p = 0.034), while peer support showed no significant relationship (β = −0.092, p = 0.662). This finding confirms the importance of teacher-driven guidance for this group and suggests their motivation is largely independent of peer interactions. In contrast, for students with mobility support needs, peer support emerged as the significant predictor of motivation (β = 0.468, p = 0.007), while teacher support showed a notably weaker and non-significant relationship (β = 0.112, p = 0.497). This highlights the importance of social dynamics and peer interactions for maintaining motivation among these students. Students with hearing support needs showed a stronger relationship with peer support (β = 0.457, p = 0.049) than with teacher support (β = 0.284, p = 0.192), though the latter approached significance in the small sample. For students with learning difficulties, both teacher support (β = 0.318, p = 0.038) and peer support (β = 0.362, p = 0.020) significantly predicted motivation, suggesting they benefit from comprehensive support systems.

The varying explanatory power of these models (Visual: R2 = 0.231; Hearing: R2 = 0.389; Learning: R2 = 0.332; Mobility: R2 = 0.267) indicates that environmental support explains different proportions of motivational variance across support needs types. This suggests that other factors—possibly including family support, as our qualitative findings later indicate—may play differential roles across these groups.

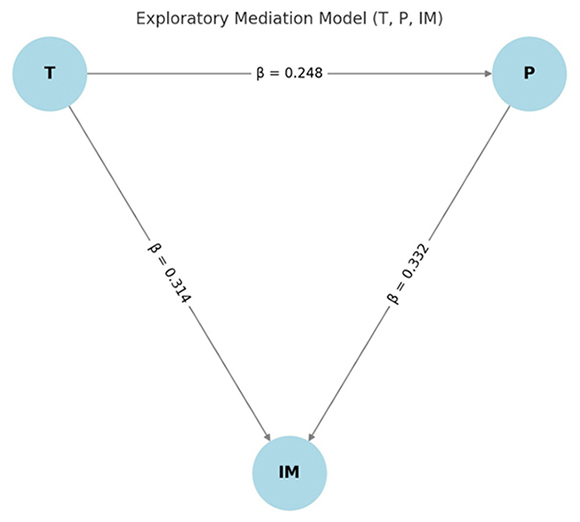

4.1.3 Exploratory mediation analysis

To complement the main analyses, an exploratory Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach was conducted to examine potential mediation pathways between teacher support, peer support, and internal motivation. The model revealed that both teacher support (β = 0.314, p = 0.003) and peer support (β = 0.332, p = 0.002) had significant direct effects on internal motivation. However, the indirect path from teacher support to internal motivation via peer support was only marginally significant (β = 0.078, p = 0.080), with confidence intervals including zero. These findings align with the regression results presented earlier, suggesting that while support within the learning environment contributes to students’ internal motivation, it accounts for a moderate portion of the variance (R2 = 0.267). Importantly, the overall model fit and the small sample size (n = 95) warrant caution in interpreting these results as conclusive.

Path diagram: exploratory mediation model: teacher support (t), peer support (p), and internal motivation (IM)

4.2 Learning environment support and internal motivation across countries (RQ2)

Building on our findings from RQ1, where we initially examined the predictive relationship between Learning Environment Support and Internal Motivation, we now take a different analytical approach for RQ2. While RQ1 focused on how teacher and peer support influence motivation, RQ2 requires us to examine these as independent variables to better understand their distinct patterns across countries and support needs. This decision to analyze Teacher Support, Peer Support, and Internal Motivation independently is driven by two key insights from RQ1: first, we found that teacher and peer support have different strengths of influence on motivation across support need groups, and second, the relationship between support and motivation isn’t uniform but varies significantly across groups. By examining these three variables independently in RQ2, we can identify specific patterns of variation across countries and support needs, potentially revealing cultural or systemic differences in how support manifests and how motivation develops in different educational contexts. RQ2a examines how LES and internal motivation vary across four European countries, while RQ2b investigates differences in these patterns among students with diverse learning needs.

4.2.1 Cross-country comparisons (RQ2a)

Looking first at the country-level analysis in Figure 2, the cross-country comparison reveals distinct patterns in how teacher support, peer support, and internal motivation manifest across the four European countries. Greece (n = 16) demonstrates the highest levels across all measures, with notably high teacher support (4.52) and strong levels of both peer support (3.77) and internal motivation (3.95). Slovenia (n = 23) and Germany (n = 24) show similar patterns, with teacher support at 4.14 and 4.11 respectively, while their peer support (Slovenia: 3.45; Germany: 3.36) and internal motivation scores (Slovenia: 3.90; Germany: 3.85) are also comparable. Poland (n = 32), which has the largest sample size, exhibits the lowest scores across all three measures, with teacher support at 3.53, peer support at 3.54, and internal motivation at 3.45.

These differences may reflect variations in how learning support is structured and perceived across different European educational contexts, although the varying sample sizes should be considered when interpreting these results.

4.2.2 Support needs comparisons (RQ2b)

When examining support patterns by country, several distinctive trends emerge, as Figure 3 illustrates. Students in Greece consistently report higher levels of support across all types of support needs, with particularly strong teacher support for students with visual support needs. This suggests that the Greek educational system may have developed effective strategies for fostering inclusive language learning environments. German data reveals relatively consistent, moderate levels of support across all types of support needs, although it should be noted that Germany had no students with visual support needs in the sample. Slovenia demonstrates particular strength in peer support mechanisms, especially among students with mobility support needs, indicating the possible success of collaborative classroom practices that promote peer interactions. Poland shows lower overall scores across most support types and support needs groups, which may reflect broader systemic challenges affecting inclusive practices rather than differences between groups.

Figure 3. Mean scores of teacher support, peer support, internal motivation for students with DLN in EFL by country.

It is important to note that the number of participants varied across countries, with Poland having the largest sample and Greece the smallest. Poland’s lower overall scores across support types point to potential systemic factors rather than specific challenges per support group. However, the data presents a complex picture that must be interpreted with caution due to sampling limitations. The uneven distribution of students across different support group in each country, and the small or absent representation of certain groups in some countries (no students with visual support needs in Germany and only one student with deaf/hard-of-hearing support needs in Slovenia), makes it difficult to draw conclusions about country-level trends.

4.3 Influences of educational factors on internal motivation and environmental factors (RQ3)

To address how educational factors influence internal motivation and environmental factors among students with diverse learning needs who learn EFL (RQ3), we examined three key educational factors: language proficiency (CEFR level), school type, and length of language study. Our analysis focused on how these factors relate to both internal motivation and environmental support factors (teacher and peer support).

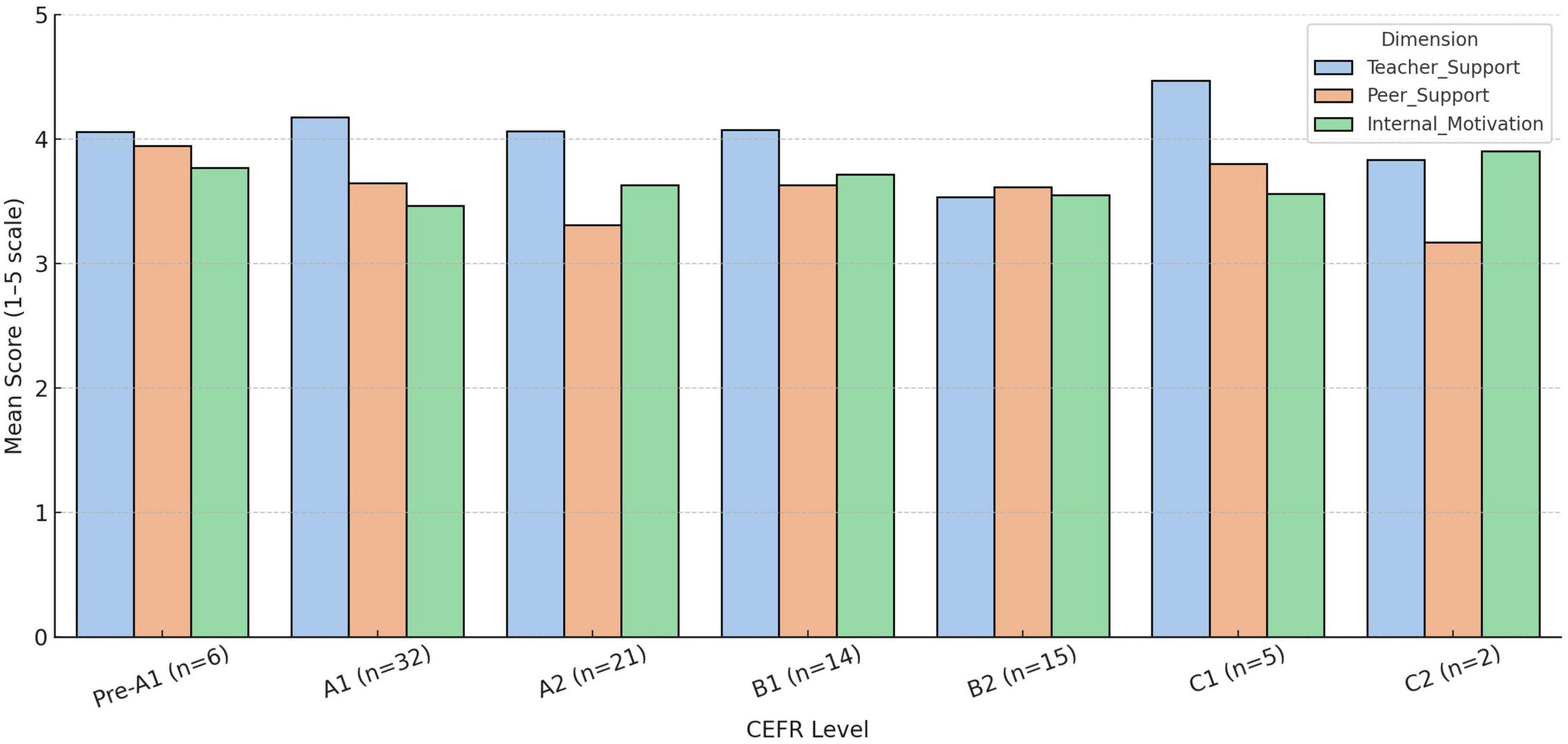

Figure 4 presents patterns across different CEFR levels, showing Teacher Support, Peer Support, and Internal Motivation for each proficiency level, along with the number of students in each level. The analysis reveals that beginning learners at Pre-A1 level (n = 6) show relatively high levels of Teacher Support (4.33) and Peer Support (4.24), suggesting strong environmental support at the initial stages of language learning. This pattern continues somewhat into A1 level (n = 31), the largest group, which maintains strong Teacher Support (4.20) but shows slightly lower Peer Support (3.68). In the intermediate levels, A2 (n = 19) shows consistent Teacher Support (4.00) but lower Peer Support (3.39), while B1 (n = 14) maintains similar patterns with Teacher Support at 4.00 and Peer Support at 3.54. Interestingly, at B2 level (n = 15), there’s a noticeable decrease in Teacher Support (3.53) while Peer Support remains moderate (3.65). This might suggest a shift in support dynamics as students’ progress in their language proficiency. At advanced levels, C1 students (n = 5) show increased Teacher Support (4.47) and Peer Support (3.98), while C2 level (n = 2), though with a small sample size, shows moderate Teacher Support (3.83) and lower Peer Support (3.19).

Figure 4. Mean levels of teacher support, peer support, and internal motivation across CEFR proficiency levels (n = 95).

While Figure 4 suggested patterns, such as higher levels of teacher and peer support at lower proficiency levels (e.g., Pre-A1 and A1), and fluctuating support levels across intermediate and advanced CEFR levels, these trends lacked statistical significance. Consequently, the observed differences across proficiency levels should be interpreted with caution, as they do not provide conclusive evidence of meaningful relationships between these factors and the internal motivation or environmental support variables. The statistical analysis conducted for RQ3 revealed no significant relationships between the examined educational factors—language proficiency (CEFR level), school type and length of language study—and internal motivation, teacher support, or peer support.

4.4 Thematic analysis of students’ experiences

Thematic analysis explored critical dimensions of students’ foreign language learning experiences, focusing on four key areas derived from open-ended interview responses:

(Q1) Digital Tools: Usage, Recommendations, and Support

(Q2) Material Formats, Assessment Strategies, and Teacher Support

(Q3) Student Perspectives on Group Work and Peer Collaboration

(Q4) Internal Motivation and Support Systems, including enjoyment, challenges, personal goals, and family influence.

Each thematic area was analyzed across the four main types of support needs represented in the study: visual impairments, hearing impairments, learning difficulties, and physical/mobility impairments. The analysis combines cross-cutting themes (e.g., technology, assessment, peer dynamics) with variation by support need, providing both breadth and specificity in understanding how students engage with language learning across different educational and national contexts. Selected student quotes illustrate these patterns, capturing both shared experiences and individual differences.

Q1 examines how students with diverse learning needs engage with assistive technologies, revealing variations influenced by age, language proficiency, and educational settings. Younger students tend to rely on teacher guidance, while older learners demonstrate more independence in exploring tools like social media and specialized applications. Higher CEFR-level students employ complex technological combinations, while lower-level students focus on fundamental tools. Q2 provides insights into the importance of structured materials, patient instruction, and adaptive assessments. Students emphasize multimodal learning approaches, extended time, and alternative evaluation formats, highlighting the need for teacher support tailored to individual needs. Q3 addresses collaborative dynamics, showing how preferences for individual, pair, or group work vary by disability type and classroom environment. Accessibility, compatibility, and clear task divisions play significant roles in shaping student collaboration preferences. Q4 explores internal motivation, highlighting how personal goals, emotional resilience, and family support influence students’ engagement with language learning. Below, a more detailed thematic analysis per type of support need is presented.

4.4.1 Q1. DT tools: usage, recommendations, and support

The analysis reveals several significant patterns in how students with diverse learning needs engage with assistive technology and support tools. Age emerges as a crucial factor in technology adoption and preferences, with younger students (ages 8–14) showing a clear inclination toward structured, teacher-guided approaches to technology use. This is evidenced by their reliance on teacher recommendations and need for consistent support in tool usage. In contrast, older students (15 +) demonstrate greater independence in selecting and implementing technological tools, often exploring and adopting new technologies on their own initiative, as seen in the case of several students using social media and independent learning applications.

Language proficiency level, as measured by CEFR, significantly influences the sophistication of tool usage. Students at higher CEFR levels (B2-C2) tend to employ more complex combinations of tools, often integrating multiple technologies to support their language learning. For example, advanced students frequently combine screen readers with specialized language learning apps or use social media platforms alongside traditional learning tools. Conversely, students at lower CEFR levels (A1-A2) typically rely on more basic translation and accessibility tools, focusing on fundamental language support rather than sophisticated language learning technologies.

The educational setting plays a crucial role in determining both access to and implementation of assistive technologies. Mainstream schools generally emphasize broader digital integration, incorporating widely available educational technology tools that can benefit all students while being adapted for those with specific needs. Special needs schools, on the other hand, tend to focus on specialized adaptive technologies tailored to specific disabilities e.g., talkers, often providing more intensive support in tool usage but potentially limiting exposure to mainstream digital learning tools. This distinction highlights the ongoing challenge of balancing specialized support with inclusive educational practices.

4.4.2 Visual impairments

Students primarily use screen readers (NVDA), Braille machines, and laptops with specialized software. Digital tools include audio recording devices and text magnification software. Several students mentioned shifting from traditional Braille machines to laptops for increased efficiency and reduced physical strain. Most students strongly recommend screen readers and digital tools over traditional Braille machines. For speaking and listening skills, students primarily utilize audio recordings and speech synthesizers, which allow them to practice pronunciation and enhance auditory comprehension. Reading skills are supported through screen readers and text magnification software, enabling students to access written materials at their own pace and preferred format. Writing tasks are accomplished using laptops equipped with specialized software and Braille machines, though many students express a preference for digital tools over traditional Braille systems due to their greater flexibility and ease of use. The integration of these tools varies based on individual needs and preferences, with many students using multiple tools in combination to support their language learning process.

Students express several key areas where additional support would enhance their learning experience. They particularly emphasize the need for better training in digital tool use, noting that while tools are often available, they lack comprehensive instruction in utilizing them effectively. Students also consistently highlight the importance of more reliable technical support, as interruptions in tool functionality can significantly impact their learning progress. Additionally, they express a strong desire for greater availability of accessible digital materials, indicating that current resources often fail to meet their specific learning needs. These support needs appear consistently across different educational settings and countries, suggesting a systemic gap in technological support infrastructure for language learning.

4.4.3 Making students’ voices heard

Example 1: “Laptop, NVDA—speech synthesizer, Word. you can install English, German, Polish speech synthesizer. I had support from other teachers like pedagogue or psychologist. In this school I don’t get support now, sometimes if I forget some tools or how to use email, I have to call my previous school for help.” Age: 13 | CEFR: B2 | Male | Slovenia | Secondary School

Example 2: “Translator, Braille typewriter. I would especially recommend the translator, it is a useful tool, although it may sometimes not work properly. I use both of these tools myself. I prefer materials in Braille. There is a printer in the school that converts letters into Braille but it doesn’t always work properly.” Age: 15 | CEFR: A2 | Female | Greece | Mainstream School

Example 3: “Enlarger. I would like to use a translator that reads for me. Listening from a recorder. My teacher sometimes suggests something about tasks but not always. audio recordings because I read very slowly in my Polish language, so I have big problems with reading in English.” Age: 14 | CEFR: A1 | Male | Poland | Special Needs School

4.4.4 Deaf/hard of hearing

Students with hearing impairments demonstrate distinct patterns in their technology use and support needs for language learning. Their current tool usage centers primarily on visual aids, subtitled content, and digital translation tools, with many actively incorporating social media platforms for language exposure and practice. The tools’ effectiveness varies across language skills, with limited options for speaking practice but strong support for listening through subtitled videos and hearing aids where applicable, while reading and writing skills benefit from digital text platforms and social media interaction. Despite the clear value of these tools, most students report receiving minimal specialized support for technology use, often developing their skills through self-teaching or peer assistance. This gap in support underscores their expressed needs for additional resources, particularly more comprehensive visual learning materials, better integration of subtitled content across learning platforms, and specialized software for pronunciation practice, suggesting a significant opportunity for improving technological support in language education for deaf and hard of hearing students.

4.4.5 Making students’ voices heard

Example 1: “I mainly use social media and especially TikTok and they help me to improve my Listening Skills and also my writing skills through comments. Apart from the hearing aid I don’t use any other tool and I don’t need any further support to use these tools.” Age: 17 | CEFR: B2 | Female | Germany | Secondary School Tools: Social media, hearing aid.

Example 2: “Subtitles for shows, none at school. Instructions are written on the blackboard, material is differentiated (school book, worksheets, tests).” Age: 16 | CEFR: C1 | Male | Poland | Secondary School.

Example 3: “When I watch YouTube, that in general, but also when for example in the morning, because I can’t find a cartoon. Not with reading. In speaking a lot. What I already know, but you can still learn some new words.” Age: 12 | CEFR: A2 | Female | Poland | Primary School.

4.4.6 Learning differences

Regarding material formats, students predominantly emphasize the need for structured, multimodal learning approaches, with many expressing preference for visual supports and clear organization of materials. The importance of explicit instruction and step-by-step presentation emerges consistently across responses. In terms of assessment practices, students highlight the value of extended time and alternative evaluation formats, with many noting the importance of having instructions broken down into manageable components. Notably, students express preference for assessment environments that allow them to demonstrate their knowledge without time pressure. Regarding pedagogical support, findings underscore the importance of patient, systematic instruction and positive reinforcement. Students particularly value teachers who provide clear explanations, break down complex tasks, and offer regular encouragement and feedback.

4.4.7 Making students’ voices heard

Example 1: “I prefer a more entertaining way of learning, more interactive with more pictures and continuous repetition of the material. The “live” content made the learning process easier for me.” Age: 16 | CEFR: B1 | Female | Greece | Secondary School.

Example 2: “It would be good to give more time and not to judge mistakes that come from dyslexia. One incident had a positive impact when my teacher believed in me and encouraged me to take the TOEIC exam despite my anxiety. When I passed, it significantly boosted my confidence. This showed me I could succeed with proper support despite my dyslexia.” Age: 17 | CEFR: B2 | Male | Greece | Secondary School.

Example 3: “I need explanation about the mistakes I make, analysis of these mistakes and then I want more exercises to solidify my competences so as to write sentences in English correctly. I want my teacher to assign me such tasks that I can develop my English while doing them.” Age: 15 | CEFR: A2 | Female | Poland | Special Needs School.

4.4.8 Physical/motor impairments

Students with physical impairments demonstrate adaptable approaches to technology use and material preferences, often focusing on tools that facilitate independent learning and comfortable access to materials. Their use of adaptive digital devices for writing and interaction reflects a strong emphasis on maintaining autonomy in their learning process. These students generally prefer digital material formats, though some express preference for traditional printed materials when they find digital interfaces distracting. The emphasis on independent access to learning materials emerges as a consistent theme across all educational settings.

4.4.9 Making students’ voices heard

Example 1: “I use a talker for German and English that can be switched between the languages so I can use it for my audio output in English. Worksheets, same as everyone.” Age: 13 | CEFR: A1 | Female | Germany | Special School.

Example 2: “I use the computer to write more easily. It is also more convenient to use the trackpad because I can’t use the mouse easily. I don’t need support. Forms in digital format because the notes are more organized and formatted.” Age: 16 | CEFR: B1 | Male | Slovenia | Secondary School Tools.

Example 3: “When I wear headphones while listening to music it helps me to improve my listening skills and focus better on the lyrics. I also use the translator. Certainly not digitally. Digital distracts me. I prefer printed material.” Age: 17 | CEFR: B2 | Female | Greece | Secondary School.

4.4.10 Q2. Material formats, assessment strategies, and teacher support

Students across different proficiency levels emphasize the importance of persistence and resilience in language learning, particularly highlighting the value of multimedia exposure through films, music, and authentic materials. Several students stress the importance of foundational knowledge before engaging with authentic materials, suggesting a scaffolded approach to language exposure. A notable theme emerges around the psychological aspects of learning, with students emphasizing the need to maintain a positive mindset despite challenges. Students also highlight the importance of consistency in support staff, particularly noting the impact of frequent changes in support teachers and the need for specialized support beyond traditional classroom instruction. The value of experiential learning and real-world language application is consistently mentioned, with students expressing desire for international exchanges and authentic communication opportunities.

4.4.11 Visual impairments

Students with visual impairments emphasize the crucial role of early intervention and appropriate technological support from primary school onward. They particularly highlight the importance of having consistent access to adapted materials and specialized staff who understand both language teaching and visual impairment needs. Several students stress the significance of proper learning conditions, specifically mentioning lighting and physical setup of learning spaces. The role of motivation and persistence emerges strongly, with students emphasizing the need to overcome initial barriers and maintain engagement despite technical challenges. Many express the desire for more integrated learning experiences that combine technology with traditional methods, suggesting a balanced approach to language acquisition. Extended time for tests was frequently highlighted as an essential requirement. Participants also expressed a need for alternative assessment formats, with a particular preference for oral examinations. Additionally, the importance of clear structure and formatting in assessments was emphasized to ensure accessibility and understanding. Teacher support and motivation for students with visual impairments centered around several common themes. There was a strong need for structured guidance to help navigate learning tasks effectively. Participants expressed appreciation for individualized attention, highlighting the importance of tailored support. Clear verbal instructions were emphasized as crucial for understanding, alongside the value of encouragement and an empathetic approach from teachers to foster motivation and confidence.

4.4.12 Making students’ voices heard

Example 1: “The oral examination certainly helps. Also, the teacher should not be cold toward the students and should certainly not make them anxious.” Age: 17 | Greece | Secondary School.

Example 2: “Having more time when I have to do reading/writing. Exercises based on listening and speaking could be a better way of assessment” Age: 16 | Greece | Secondary School.

Example 3: “The teacher always suggests testing me orally, even in everyday spelling. We also use English a lot in class, and she encourages us to participate in the discussion” Age: 17 | CEFR: B2 | Female | Greece | Secondary School.

Example 4: “The lighting conditions are very important. I used to have a problem with the classroom where we were doing English, I was having a hard time reading because of bad lighting and the teacher arranged for us to have class elsewhere so I was able to participate more actively.” Age: 15 | CEFR: B1 | Female | Greece | Secondary School.

Example 5: “To give me extra exercises and write them down in the notebook so that I can do them in the KET (Key English Test, now A2 Key) with the teacher” Age: 13 | CEFR: A1 | Male | Poland | Special Needs School.

4.4.13 Deaf/hard of hearing

Common themes in assessment needs and accommodation include the necessity for written instructions during tests, allowing students to refer back to guidelines as needed. Extended time is often essential for processing information, enabling thorough comprehension and response formulation. Visual support during assessments can aid understanding and retention of material. Additionally, alternative assessment methods, such as portfolios or project-based evaluations, may better capture a student’s abilities and learning progress. Common themes in teacher emphasize the need for visual teaching methods, such as diagrams, written instructions, and visual aids, to support understanding. The importance of face-to-face communication is also critical, allowing students to read facial expressions, lips, or sign language for better comprehension. Repetition and clarification are valued to ensure that students fully grasp concepts, while patient teachers are appreciated for taking the time to address individual needs and foster an inclusive learning environment.

4.4.14 Making students’ voices heard

Example 1: “After playing the recording, she asks if everything was clear, as I said, she once gave me a printed text. A lady often comes up to me and asks if I heard everything. She also tries to talk facing me so that I can see her mouth in case of problems.” Age: 14 | CEFR: A2 | Female | Poland | Special Needs School.

Example 2: “I get the material sent to me by e-mail and then I start preparing. So, I sit at the computer, and I read until the test.” Age: 16 | CEFR: B1 | Male | Germany | Secondary School.

Example 3: “The teacher guides me exactly right, helps me if I get confused. He pays more attention. The teacher also needs to know sign language.” Age: 15 | CEFR: B1 | Male | Germany | Special Needs School.

Example 4: “Usually I want my teacher to know sign language fluently. To tell you the truth I am not satisfied with my English teacher. She does not know how to work with young people and motivate us.” Age: 16 | CEFR: B2 | Female | Poland | Secondary School.

Example 5: “The teacher puts on the recording to listen to a few times during the test. If something goes wrong on the test, for example I’m disappointed. And I ask the teacher if I can improve my grade and the teacher gives me the chance to write the test again.” Age: 14 | CEFR: A2 | Female | Greece | Secondary School.

Example 6: “Sometimes, there are classes that don’t have good acoustics. And I’m not talking about listening activities but also when someone is just talking. For example, echoes are created and that makes it even more difficult” Age: 16 | CEFR: B1 | Female | Poland | Secondary School.

Example 7: “The teacher appreciates my commitment despite my difficulties. She tries to help me. She introduces an additional explanation. I need extra time, and the teacher provides me with that. When it comes to grades, she gives me the opportunity to improve the grades.” Age: 16 | CEFR: B2 | Male | Poland | Secondary School.

4.4.15 Learning difficulties

Regarding material formats and presentation, findings highlight the importance of structured and clear presentations, ensuring that information is well-organized and easy to follow. There is a strong preference for multimodal materials, combining auditory, visual, and written formats to cater to diverse learning styles. Visual supports accompanied by written text are particularly beneficial for reinforcing understanding, while step-by-step instructions provide guidance and clarity, enabling learners to navigate tasks effectively. In terms of assessment practices, common themes include the provision of extended time for tests to support thorough processing and response formulation. Simplified instructions help ensure clarity and reduce confusion, while breaking down complex tasks into manageable steps aids comprehension and completion. Additionally, alternative assessment formats, such as oral exams, portfolios, or project-based evaluations, allow students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills in ways that align with their strengths. Regarding teacher pedagogical support and motivation, findings emphasize the importance of patient explanations to ensure students fully understand the material without feeling rushed or overwhelmed. Positive reinforcement plays a crucial role in building confidence and encouraging continued effort. Breaking down complex tasks into smaller, manageable steps helps students approach challenges more effectively. Regular feedback and encouragement are essential for guiding progress, fostering motivation, and maintaining a supportive learning environment.

4.4.16 Making students’ voices heard

Example 1: “Watch as many films as you can to make your English go as well as possible. Because I really learnt a lot. I learnt a lot of words and I learnt a lot of films and then I already knew those things.” Age: 14 | CEFR: A2 | Male | Poland | Special Needs School.

Example 2: “I prefer notes our teacher prepares for us. There are too many pictures and words in the textbooks—there is a lot of a mess there. I cannot concentrate.” Age: 15 | CEFR: B1 | Male | Poland | Special Needs School.

Example 3: “More time, colored sheet, enlarged font. And underlined key words.” Age: 14 | CEFR: A2 | Female | Slovenia | Secondary School.

Example 4: “I cannot write correctly – I have dyspraxia. I want to be assessed not for the quality of my writing, but my actual language competences.” Age: 16 | CEFR: B1 | Male | Poland | Secondary School.

Example 5: “I don’t like writing and I don’t like long tasks in general. I prefer a short answer exam. Digital assessment helps me.” Age: 13 | CEFR: A1 | Male | Germany | Special Needs School.

Example 6: “I think it all starts in primary school. Unfortunately, however, we did not have the necessary qualified staff in primary school, which meant that valuable time was lost and it was more difficult to keep up with our classmates.” Age: 16 | CEFR: B2 | Female | Greece | Secondary School.

4.4.17 Physical/Motor Impairments

Students consistently emphasize the importance of accessible learning environments that allow for comfortable, independent participation. Many highlight how physical comfort significantly impacts their ability to engage in language learning activities. The role of adaptable learning approaches emerges as crucial, with students appreciating teachers who can modify activities to ensure full participation while maintaining high academic standards. Several students mention the value of digital tools in overcoming physical barriers to language learning, suggesting that technology plays a crucial role in their learning success. Students emphasize the importance of adaptable formats that accommodate their physical needs, with many preferring electronic materials that can be accessed through assistive devices. The physical arrangement and accessibility of materials emerge as crucial factors in their learning experience. In terms of assessment practices, students highlight the need for flexible testing environments and adapted writing methods, including the use of computers or assistive devices. Extended time provisions are valued not primarily for cognitive processing but for physical task completion. Alternative response formats and adaptive technologies play a vital role in enabling students to demonstrate their knowledge effectively. Regarding pedagogical support and motivation, findings underscore the importance of teachers’ understanding of physical limitations while maintaining high academic expectations. Support focuses on ensuring physical accessibility of learning activities while promoting independence and full participation in language learning tasks. Teachers’ awareness of fatigue and physical comfort emerges as crucial for maintaining student engagement and motivation.

4.4.18 Making students’ voices heard

Example 1: “I prefer digital material. I have everything on the computer, and I write. The only thing I write in a workbook.” Age: 17 | CEFR: B2 | Female | Slovenia | Secondary School.

Example 2: “iPad, sometimes dictionary, Special needs schoolbook. We all get enough time for tests.” Age: 13 | CEFR: A1 | Male | Germany | Special Needs School.

Example 3: “I write all assessments outside class. That’s good. It’s quieter, and I don’t have to move from one class to another when 45 min are up.” Age: 15 | CEFR: B1 | Male | Poland | Special Needs School.

Example 4: “I write the tests on my own with a school assistant whom I dictate a lot of my answers, I get more time and usually differentiated tasks.” Age: 14 | CEFR: A1 | Male | Germany | Special Needs School.

Example 5: “I want in my school some international exchanges so I can get to know people from abroad and communicate with them in English. I could develop my vocabulary and grammar and I will feel more confident” Age: 15 | CEFR: B1 | Female | Poland | Special Needs School.

Example 6: “It’s helpful when the teacher sits with me and reminds me to work. The teacher helps with instructions and during tasks.” Age: 15 | CEFR: A2 | Female | Germany | Special Needs School.

Example 7: “There should not only be parallel support in schools but also other specialties such as speech and language therapists in the school, as well as a permanent psychologist” Age: 17 | CEFR: B2 | Male | Greece | Secondary School.

Example 7: “Unfortunately I do not feel support from my English teacher. My teacher does not like me because I am all the time moving around and hyperactive and she does not like it” Age: 13 | CEFR: A1 | Male | Poland | Primary School.

4.4.19 Q3. Student perspectives on group work and peer collaboration:

4.4.19.1 Visual impairments

Students generally express varied preferences based on task complexity, accessibility needs, and classroom dynamics. Individual work is often preferred for tasks requiring assistive technological use or specialized materials, while pair work is favored for activities involving verbal communication and mutual support. Group work preferences are typically contingent on classroom arrangement and accessibility considerations.

4.4.20 Making students’ voices heard

Example 1: “Hard to work alone. I prefer to work in pairs, so the other person has a more supportive role.” Age: 15 | CEFR: B1 | Female | Greece | Secondary School,

Example 2: “Definitely in couples because it is more direct communication with your partner. In groups it is difficult to interpret all the information.” Age: 17 | CEFR: B2 | Male | Greece | Secondary School,

Example 3: “I prefer to work alone. I want to be responsible for the result. Also, in groups I could work with people who have common ideas and visions.” Age: 16 | CEFR: A2 | Female | Greece | Secondary School,

4.4.21 Deaf/hard of hearing

Analysis shows that students with hearing impairments demonstrate distinct patterns in their collaborative preferences. Many express a strong preference for pair work or small group settings where visual communication is more manageable. The importance of clear lines and reduced background noise emerges as a crucial factor in group work preferences. Students often emphasize the need for structured communication protocols in group settings.

4.4.22 Making students’ voices heard

Example 1: “I prefer alone or in pairs. Groups give me a hard time because it’s hard for me to understand who’s talking at any given time.” Age: 16 | CEFR: B1 | Female | Poland | Secondary School,

Example 2: “In pairs because you can take a cue from each other.” Age: 14 | CEFR: A2 | Male | Poland | Special Needs School,

Example 3: “It is often too loud in class which makes it hard for me. In that case, I inform my teacher and go to work outside with my assistant, but I would prefer to work in class with all my peers, but in quiet. I like to work in small groups.” Age: 15 | CEFR: B1 | Male | Germany | Special Needs School,

4.4.23 Learning difficulties

Analysis reveals that students with learning difficulties show diverse preferences in collaborative work, largely influenced by their specific learning needs and classroom dynamics. A significant pattern emerges around the desire for structured support while maintaining autonomy. Many students express preference for pair work over larger groups, citing better focus and more direct support opportunities. The importance of partner compatibility and clear task division appears consistently in student responses.

4.4.24 Making students’ voices heard

Example 1: “First of all, I find it easier if we go in pairs or if we go in groups. Because if I get lost somewhere or if I don’t know how to do something, they can help me. Then it’s much easier for me if we work together, if I forget something.” Age: 13 | CEFR: A1 | Female | Poland | Primary School,

Example 2: “I prefer working in a group and pairs. Because there is always hope that if I don’t know something, don’t know how to do something, someone in the group does. I need some kind of support in the classroom. I don’t feel stressed then.” Age: 14 | CEFR: A2 | Male | Germany | Special Needs School,