- 1Institute of Crop Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, National Engineering Research Center of Crop Molecular Breeding, Beijing, China

- 2College of Life Sciences, Shanxi University, Taiyuan, China

- 3College of Agriculture, Shanxi Agricultural University, Jinzhong, China

- 4College of Agronomy and Biotechnology, Hebei Normal University of Science and Technology, Qinhuangdao, China

- 5Zhaoxian Experiment Station, Shijiazhuang Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences, Shijiazhuang, China

- 6Xinxiang Innovation Center for Breeding Technology of Dwarf-Male-Sterile Wheat, Xinxiang, China

Winter frost has been considered the primary limiting factor in wheat production. Shimai 12 is an elite wheat cultivar grown in central and southern Hebei province of China, but sensitive to winter frost. In this study, the winter frost tolerant cultivar Lunxuan 103 was bred by introducing the recessive allele vrn-D1 from winter wheat Shijiazhuang 8 (frost tolerance) into Shimai 12 using marker-assisted selection (MAS). Different from Shimai 12, Lunxuan 103 exhibited a winter growth habit with strong winter frost tolerance. In the Shimai 12 × Shijiazhuang 8 population, the winter progenies (vrn-D1vrn-D1) had significantly lower winter-killed seedling/tiller rates than spring progenies (Vrn-D1aVrn-D1a), and the consistent result was observed in an association population. Winter frost damage caused a significant decrease in grain yield and spike number/m2 in Shimai 12, but not in Lunxuan 103 and Shijiazhuang 8. The time-course expression analysis showed that the transcript accumulation levels of the cold-responsive genes were higher in Lunxuan 103 and Shijiazhuang 8 than in Shimai 12. Lunxuan 103 possessed the same alleles as its parents in the loci for plant height, vernalization, and photoperiod, except for the vernalization gene Vrn-D1. An analysis of genomic composition showed that the two parents contributed similar proportions of genetic compositions to Lunxuan 103. This study provides an example of the improvement of winter frost tolerance by introducing the recessive vernalization gene in bread wheat.

Introduction

Low-temperature stress is the primary limiting factor that determines the growth, development, and geographical distribution of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) (Laudencia-Chingcuanco et al., 2011; Vítámvás et al., 2019). Frost damage occurs frequently in northern and Eastern Europe, North America, and China, and greatly threatens wheat production (Babben et al., 2018; Muhammad et al., 2021). Tolerance to low temperatures is essential for the fall-planted temperate cereals to survive the freezing temperatures during the winter season (Dhillon et al., 2010). Winter wheat is usually planted in autumn and must have substantial tolerance to winter frost during winter and resumes normal growth in the next spring (Galiba et al., 2009; Case et al., 2014). Different from winter frost, spring radiation frost usually takes place at the late vegetative and reproductive stages and results in anther sterility, floret, spike abortion, and damage to developing grains (Xiao et al., 2018; Muhammad et al., 2021).

Three groups of genes conferring vernalization (Vrn), photoperiod (Ppd), and CBF (C-repeat binding factors) transcription factors determine the frost tolerance of wheat (Galiba et al., 2009; Janmohammadi and Mahfoozi, 2013; Babben et al., 2018). Vernalization is a physiological process for winter and biennial species, which requires exposure to a period of low temperature to generate flowering competence (Xu and Chong, 2018; Xu S. et al., 2021). The response to vernalization in wheat is mainly controlled by five genes, Vrn-A1, Vrn-B1, and Vrn-D1 on chromosomes 5A, 5B, and 5D, Vrn-D4 on chromosome 5D, and Vrn-B3 on chromosome 7B (Fu et al., 2005; Yan et al., 2006; Kippes et al., 2015). The alleles at locus Vrn-D1 control three types of growth habits, in which the dominant alleles Vrn-D1a and Vrn-D1b confer the spring and facultative growth habits, respectively, and the recessive allele vrn-D1 is related to the winter growth habit (Fu et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2012). Two dominant alleles share the same deletion in the first intron but have a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mutation at the −161 bp position in the promoter region (Zhang et al., 2012).

Low-temperature acclimation is a process that makes plants acquire winter frost tolerance after exposure to nonfreezing temperatures (Shi et al., 2018). The requirement for nonfreezing low temperature is common to both low-temperature acclimation and vernalization, indicating the potential connection between the two processes (Dhillon et al., 2010; Xu and Chong, 2018). Winter wheat shows a clear decline in frost tolerance when the requirement of vernalization is met (Linmin and Fowler, 2006). Several major QTL Fr-A1, Fr-B1, and Fr-D1 for wheat frost tolerance are located on the same homeologous group 5 chromosomes as the vernalization genes Vrn-A1, Vrn-B1, and Vrn-D1 (Sutka and Snape, 1989; Snape et al., 2001; Sutka, 2001; Tóth et al., 2003; Babben et al., 2018). Previous studies have found that wheat cultivars with the dominant Vrn-A1a or Vrn-A1b alleles were more sensitive to low temperature than those carrying the dominant Vrn-B1 or Vrn-D1 alleles, but they were more sensitive than the cultivars carrying the recessive alleles (Koemel et al., 2004; Reddy et al., 2006). The recessive allele vrn-A1 can increase freezing tolerance between 2.1- and 2.4-folds in winter and spring wheat compared to the dominant allele Vrn-A1, respectively (Linmin and Fowler, 2006). These results suggest that the vernalization genes play an important role in the regulation of winter frost tolerance, and the recessive vrn-1 allele is strongly associated with frost tolerance.

The Yellow and Huai River Valley Winter Wheat Zone (YHWWZ) is the largest wheat-growing region in China, where frost damage has been one of the primary constraints to wheat production (Zhao et al., 2020). Hebei province is located across two wheat ecological zones, that is, the Northern Winter Wheat Zone (NWWZ) in the northern part and the YHWWZ in the southern part of the province (Li H.J. et al., 2019). Frost damage caused by low temperature during long-term winter mainly occurs in northern Hebei, whereas sudden temperature decline in early winter mainly occurs in the central-southern province (Dai et al., 2014). In the central and southern Hebei, some cultivars grow fast in warm winter due to less vernalization requirement. A sudden drop in ambient temperature at the seedling stage causes extensive winter frost injury and losses in grain yield. The most serious winter frost resulted in winterkill damage in 30% of the wheat acreage in that region in 2009 (Wang et al., 2013). It is necessary to improve winter frost tolerance in order to warrant safe production in this area.

Shimai 12, a wheat cultivar with high-yielding potential and early maturity, was commercially released as a facultative wheat cultivar in 2004 (Wu, 2005). However, it was withdrawn from production due to its sensitivity to winter frost causing serious economic losses in 2005 and 2009 (Wang et al., 2013). Shimai 12 shows spring growth habit and carries the dominant Vrn-D1a allele at the Vrn-D1 locus, indicating that it is a typical spring wheat cultivar (Zhang et al., 2010, 2012). Hence, the poor winter frost tolerance of Shimai 12 is probably attributed to its spring growth habit.

The present study was carried out to determine the effectiveness of Vrn-D1 in improving winter freezing tolerance by introducing the recessive vrn-D1 allele at the Vrn-D1 locus into Shimai 12 resulting in the development of Lunxuan 103.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

In 2003, Shijiazhuang 8 (Jimai 38/Shi 91-5065, vrn-D1vrn-D1), a high-yielding winter wheat cultivar with better winter frost tolerance and high kernel weight, was crossed to a spring wheat cultivar Shimai 12 (Shi 91-5096/Jimai 23, Vrn-D1aVrn-D1a). The F1 plants showed large spike, high thousand kernel weight (TKW), and mid-parent heterosis in plant height. The F2 plants with <70 cm in height, >45 g in TKW, and powdery mildew resistance were selected in 2005. One-half of seeds from each F2 individual differentiated as winter/spring growth habits at Guyuan experimental station (41°67′N and 115°69′E) of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS) in Hebei in summer and 321 F3 plants with a winter growth habit were selected. In 2006, another half of the F2 seeds were evaluated for major agronomic traits at the Zhaoxian experimental station (37°87′N and 114°83′E) of CAAS in Hebei. Based on the overall performances at the two locations combined with molecular marker-assisted selection (MAS) at the Vrn-D1 locus, 126 F3 lines carrying the recessive vrn-D1vrn-D1 genotype were selected for evaluating their yield-related traits and the lodging resistance in the next generation. An F5 line RS03101-101-12-2 having a grain yield of 11.3% higher than the control Shi 4185 was selected in 2008. The F6 and F7 progenies of this line were further evaluated for yield-related traits, and finally, line RS03101-101-12-2-3-1 was advanced to yield assessment. It was commercially released as Lunxuan 103 in Hebei province in 2015 (Supplementary Figure 1), and subsequently in Shanxi, Shandong, and Tianjin in 2017, 2018, and 2019, respectively.

Shimai 12 (frost sensitivity) was crossed to Shijiazhuang 8 (frost tolerance) to generate the F2 and F3 populations. A natural population comprising 110 wheat cultivars was used to compare the difference in frost tolerance between the Vrn-D1aVrn-D1a genotype (50 spring cultivars) and the vrn-D1vrn-D1 genotype (50 winter cultivars) (Supplementary Table 1).

Developmental Morphology of Inflorescence and Response to Vernalization

Under the long-day condition (16 h light/8 h dark cycle), 20 germinated seeds of each genotype were sown in plastic pots, with two replicates. All genotypes were vernalized in a chamber at 4°C for 35 days and transferred to a light growth chamber under 16 h day length at 22°C and 8 h dark length at 18°C. Non-vernalized seedlings (0 days of cold treatment) as control were directly grown in the light growth chamber. For each treatment, three plants from each genotype were sampled for observing the developmental morphology of inflorescence using a stereoscopic microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Days from sowing to the double ridge stage were used to measure the response to vernalization as described by Guo et al. (2015).

Field Trials and Phenotypic Evaluation

Field Trials

During 2017/2018, 2018/2019, and 2020/2021 wheat growing seasons, field trials were conducted at the Shunyi Experimental Station (40°23′N and 116°57′E, 48 m above sea level) (SY) of CAAS in Beijing, the Zhaoxian Experimental Station (37°87′N and 114°83′E, 44 m above sea level) (ZX) of Shijiazhuang Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences in Hebei province, the Dingxiang Experimental Station (38°50′N and 112°95′E, 866 m above sea level) (DX) of Shanxi Agricultural University (SXAU) in Shanxi, and the Taigu Experimental Station (37°42′N and 112°58′E, 799 m above sea level) (TG) of SXAU in Shanxi. The temperature information on each site is shown in Supplementary Figure 2. Field management, including fertilizers, irrigation, and management of weeds, diseases, and pests, was conducted as described previously (Meng et al., 2016).

Winter hardiness of the Shimai 12 × Shijiazhuang 8 F2 and F3 populations and a panel of wheat cultivars were evaluated at SY (2021SY), DX (2021DX), and TG (2021TG) during the 2020/2021 cropping season. All wheat entries were arranged in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with two replicates. Each plot consisted of two rows, 2 m in length, 0.25 m apart, and 40 seeds in each row.

Lunxuan 103 and its parents were arranged in RCBD with six replicates, of which three replicates were used for evaluating winter frost tolerance and the rest three for investigating the agronomic traits. Winter frost tolerance was investigated at SY (2018SY) and ZX (2018ZX) during the 2017/2018 cropping season, and SY (2019SY) during the 2018/2019 cropping season, respectively. The agronomic traits were investigated at 2018SY, 2018ZX, and ZX (2019ZX) during the 2018/2019 cropping season. Each plot contained six rows, 6 m in length and 20 cm apart at site SY, and 7.5 m in length and 20 cm apart at each site, with the seeding rates 330, 300, and 300 per m2 at 2018/2019SY, 2018ZX, and 2019ZX environments, respectively.

Winter Frost Tolerance

Winter frost tolerance was evaluated as described by the National Winter Wheat Regional Trials of China. At the three-leave stage, the total number of seedlings was investigated in 1 m double rows in a two-row plot or two sampling sites with 1-m double rows each selected along the diagonals in a six-row plot. When the daily mean temperature is <3°C, the total number of tillers was investigated in each environment. When new leaves were visible without the appearance of new tillers in spring, all seedlings at each sampling site were dug out for counting the number of winter-killed seedlings and tillers. Winter-killed seedling/tiller rates (%) were calculated by the number of winter-killed seedlings/tillers divided by the total number of seedlings/tillers before winter.

Investigation of Agronomic Traits

The agronomic traits, including grain yield (kg/ha), kernel number per spike, spike number/m2, TKW (g), plant height (cm), and heading date (d), were assessed at 2018SY, 2018ZX, and 2019ZX environments, as previously described (Meng et al., 2016).

Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

Twenty germinated seeds of each genotype were sown in plastic pots and grown in a growth chamber for 14 d under the long-day condition (16 h light at 22°C/8 h dark at 18°C), with three replicates. To analyze the gene expression patterns, 14-d-old seedlings were grown at 4°C. Five leaves for each genotype were collected at 0 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 2 d, 7 d, 14 d, 28 d, and 42 d. The total RNA extraction (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The first-strand of complementary DNA was synthesized using HiScript® III All-in-one RT SuperMix Perfect for qPCR (Vazyme # R333, Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd, Nanjing, China). The transcript levels of genes Vrn-D1, TaCBF12, Wcs120, and Wcor410 were determined by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) using a CFX Touch Real-Time PCR system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States) with the gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 2), and Actin was used as the internal reference gene. The reaction was carried out in a total volume of 20 μl consisting of 10 μl of 2 × Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd, Najing, China), 2 μl of cDNA (25 ng/μL), 0.5 μl of 10 μmol/L of each primer, and 7 μl of nuclease-free H2O. The amplification procedure was set as described by Xu K. et al. (2021). The relative expression level for each gene was calculated with the 2–ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). All data are presented as the means of three biological replicates.

Marker and Genomic Composition Analyses

Twenty-one functional markers (Supplementary Table 3) specific for genes conferring plant height, vernalization, and photoperiod were used to differentiate alleles in Lunxuan 103 and its parents and association population (Supplementary Table 1). DNA amplification was carried out in a 20-μl reaction volume consisting of 1 μl of 50–100 ng/μl DNA, 1 μl of 10 μmol/L of each primer, 10 μl of 2 × Taq PCR Master Mix (Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), and 7 μl of sterilized ddH2O. The thermal cycler reaction was set at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 50°C to 64°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 1 to 2 min, and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were separated as described previously (Li T. et al., 2019).

Wheat cultivars were also genotyped using the Affymetrix Wheat 55K SNP array by China Golden Marker Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China. After sample and marker quality control, data were processed using the Apt-genotype-axion, Probeset metrics, and Probeset classification modules by Axion Analysis Suite software (version 5.1.1) (Thermo Fisher Scientific-CN Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).1 Sequences of SNPs were blasted against the Chinese Spring reference genome sequences (IWGSC RefSeq v1.0) to determine their chromosomal and physical locations.2 An R package was used to construct the genomic composition map (Beijing Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The GO (Gene Ontology) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) enrichment analyses were performed as described by Li et al. (2018).

Statistical Analysis

Phenotypic differences in winter frost tolerance and agronomic traits among cultivars were tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA) in the SPSS software 26.0 (International Business Machines Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States), and multiple comparison analysis was performed using the least significant difference (LSD) test at P < 0.05. The differences in winter frost between genotypes in the association population were determined by the t-test in the SPSS software 26.0 (Wang et al., 2021).

Results

Inflorescence Development and Response to Vernalization

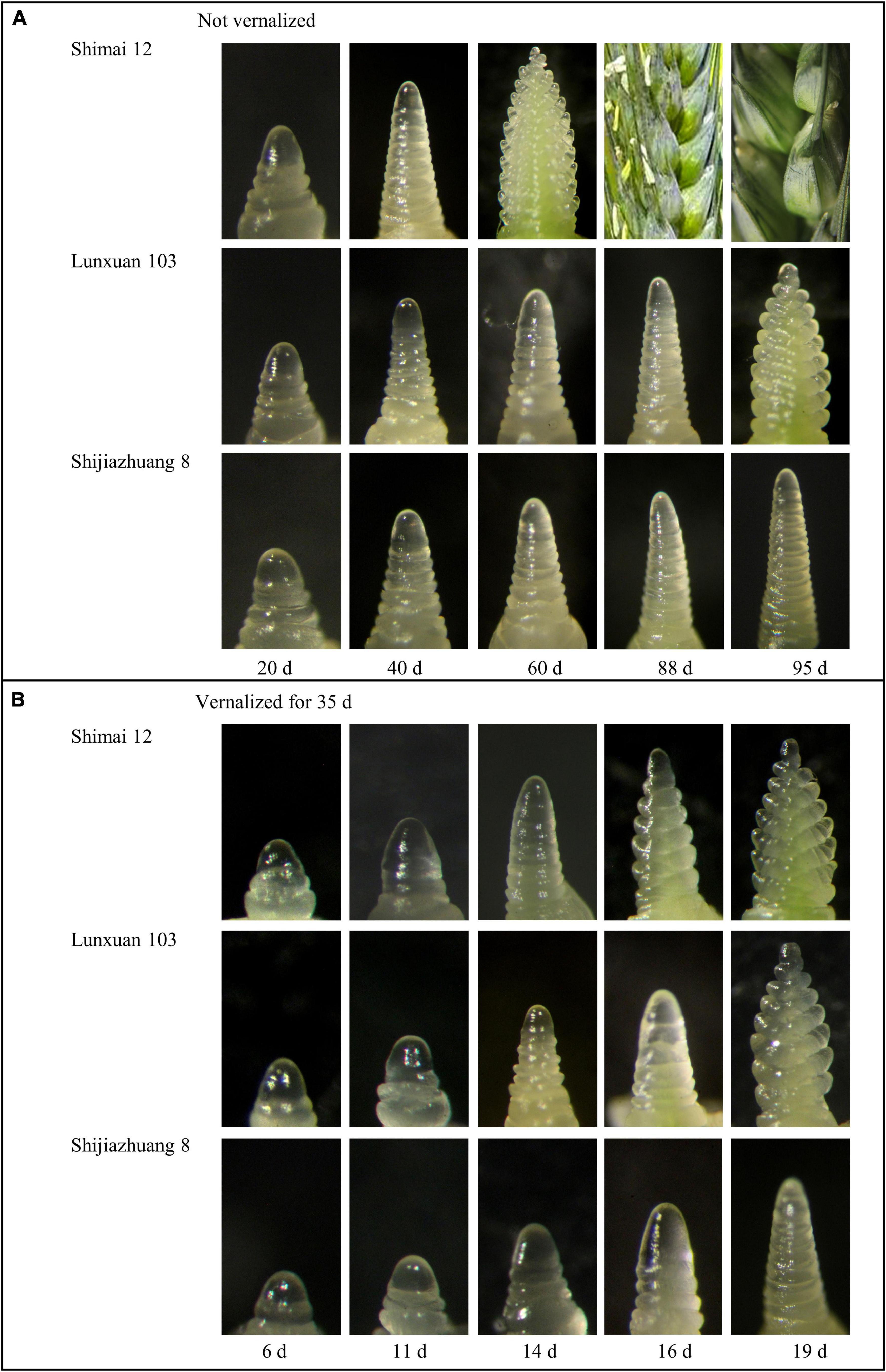

There was an obvious difference in spike differentiation among the three genotypes without vernalization (Figure 1A). Lunxuan 103 and its parents, Shimai 12 and Shijiazhuang 8, experienced the double ridge stage at 88, 40, and 95 d, respectively. The inflorescence of Shijiazhuang 8 elongated slowly and the spike development did not reach the double ridge stage until 95 d, at which Shimai 12 began grain-filling and Lunxuan 103 was at the glume differentiation stage (Figure 1A). When vernalized for 35 d, days to double ridge stage for Shimai 12, Lunxuan 103, and Shijiazhuang 8 were 14, 16, and 19 d, respectively (Figure 1B). The response to vernalization was 72 d for Lunxuan 103, 26 d for Shimai 12, and 76 d for Shijiazhuang 8. This shows that Lunxuan 103 is a typical winter cultivar with a strong response to vernalization (Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 1. Inflorescence development of Lunxuan 103 and its parents, Shijiazhuang 8 and Shimai 12, with vernalization for 0 d (A) and 35 d (B) followed by growth under 16 h day length at 22°C and 8 h dark length at 18°C.

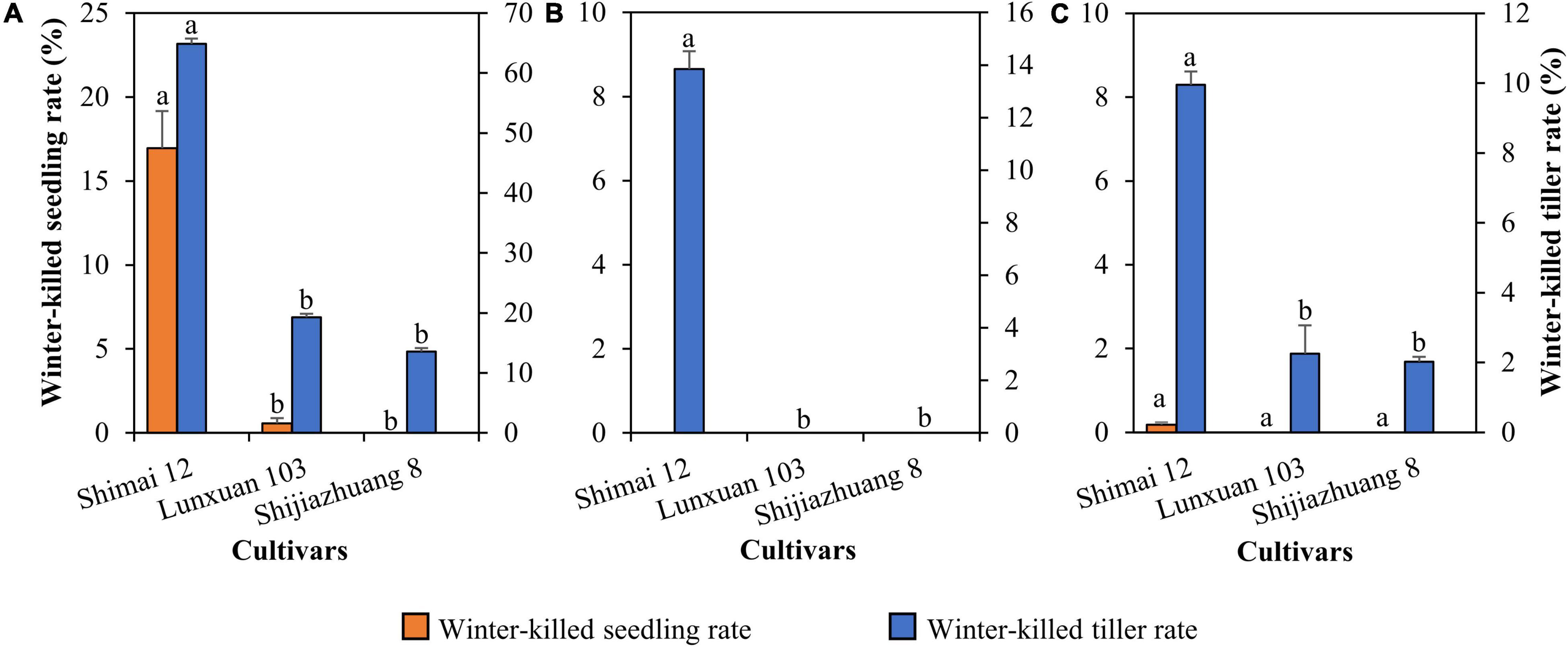

Winter Frost Tolerance of Lunxuan 103 in Comparison to the Parent Lines

Compared to Shimai 12, the winter frost tolerance of Lunxuan 103 was significantly improved, and the rates of winter-killed seedling and winter-killed tiller were reduced by 16.4 and 45.6% (P < 0.05) at 2018SY, but no difference was observed between Lunxuan 103 and Shijiazhuang 8 (Figure 2A). There was a significant difference in winter-killed tiller rate between Lunxuan 103 and Shimai 12 at 2018ZX (Figure 2B), even though no dead seedlings were found for the three genotypes. The result in 2019SY was consistent with that in 2018ZX (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Comparison of freeze-killed seedlings and tillers for Lunxuan 103 and its parents Shijiazhuang 8 and Shimai 12 at 2018SY (A), 2018ZX (B), and 2019SY (C). Multiple comparisons for each trait were performed using the least significant difference (LSD) test and different letters above the error bars indicate significant differences among cultivars at P < 0.05.

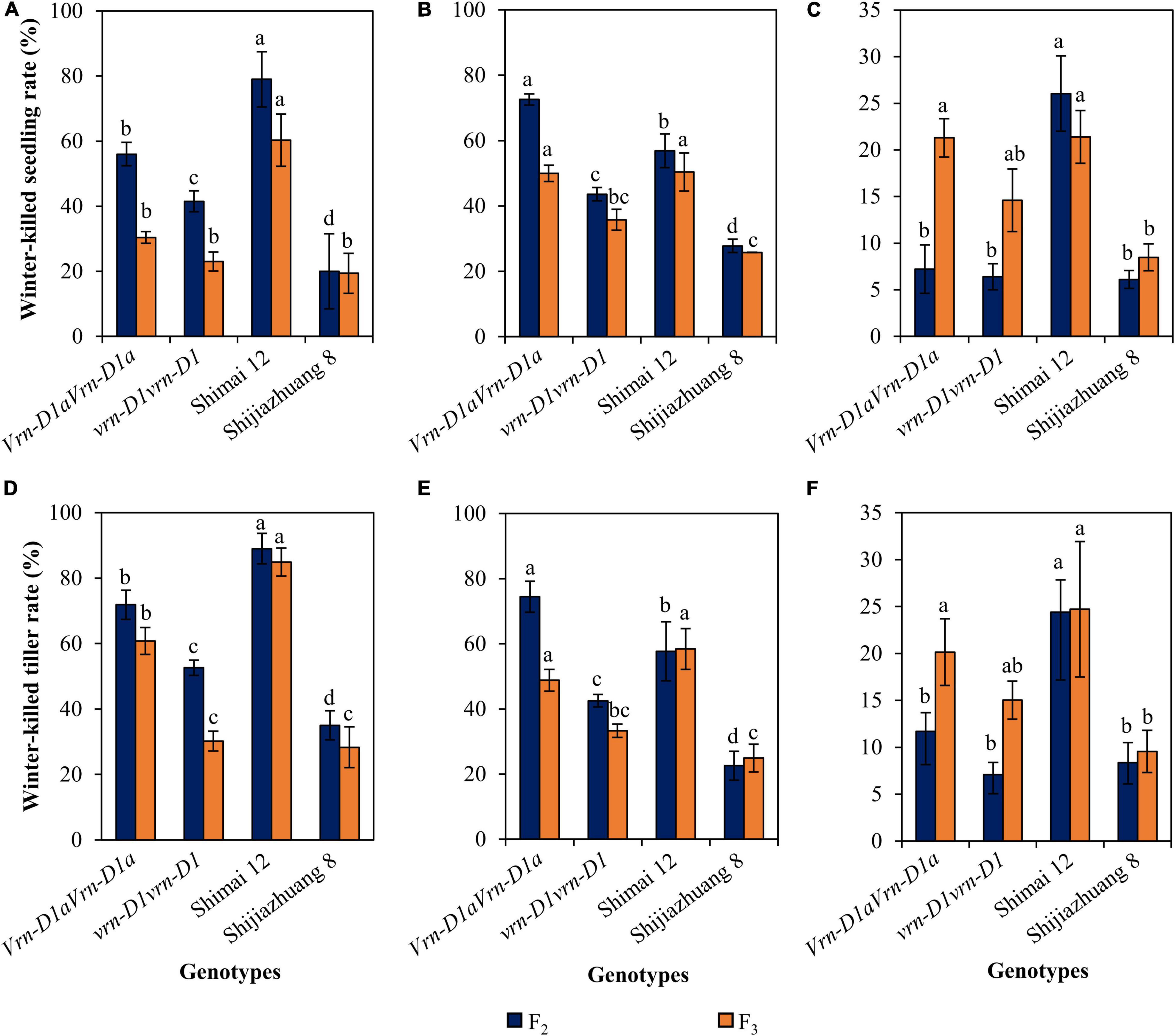

Relationship Between Different Alleles at the Vrn-D1 Locus and Winter Frost Tolerance

The progenies of cross Shimai 12 × Shijiazhuang 8 varied in winter frost tolerance at the three environments (Figure 3). Compared to the Vrn-D1aVrn-D1a genotype, the winter-killed seedling rate of the vrn-D1vrn-D1 genotype was reduced by 14.5% (P < 0.05, 2021SY), 29.0% (P < 0.05, 2021DX), and 0.9% (2021TG) in the F2 generation, and 7.4% (2021SY), 14.2% (P < 0.05, 2021DX), and 6.7% (2021TG) in the F3 generation. The winter-killed tiller rate decreased by 19.3% (P < 0.05, 2021SY), 32.0% (P < 0.05, 2021DX), and 4.6% (2021TG) in the F2 generation, and 30.7% (P < 0.05, 2021SY), 15.5% (P < 0.05, 2021DX), and 5.1% (2021TG) in the F3 generation.

Figure 3. Comparison of winter-killed seedling and tiller rates between genotypes vrn-D1vrn-D1 and Vrn-D1aVrn-D1a in the Shimai 12 × Shijiazhuang 8 F2 and F3 populations at 2021SY (A,D), 2021DX (B,E), and 2021TG (C,F). In the F2 population, the numbers of genotypes vrn-D1vrn-D1 and Vrn-D1aVrn-D1a are 764, 1091, and 1048, and 57, 108, and 102 at 2021SY, 2021DX, and 2021TG, respectively. In the F3 population, the numbers of genotypes, vrn-D1vrn-D1 and Vrn-D1aVrn-D1a, are 22 and 8, respectively. Multiple comparisons were performed for each trait using the least significant difference (LSD) test and different letters above the error bars indicate significant differences among genotypes and parents at P < 0.05.

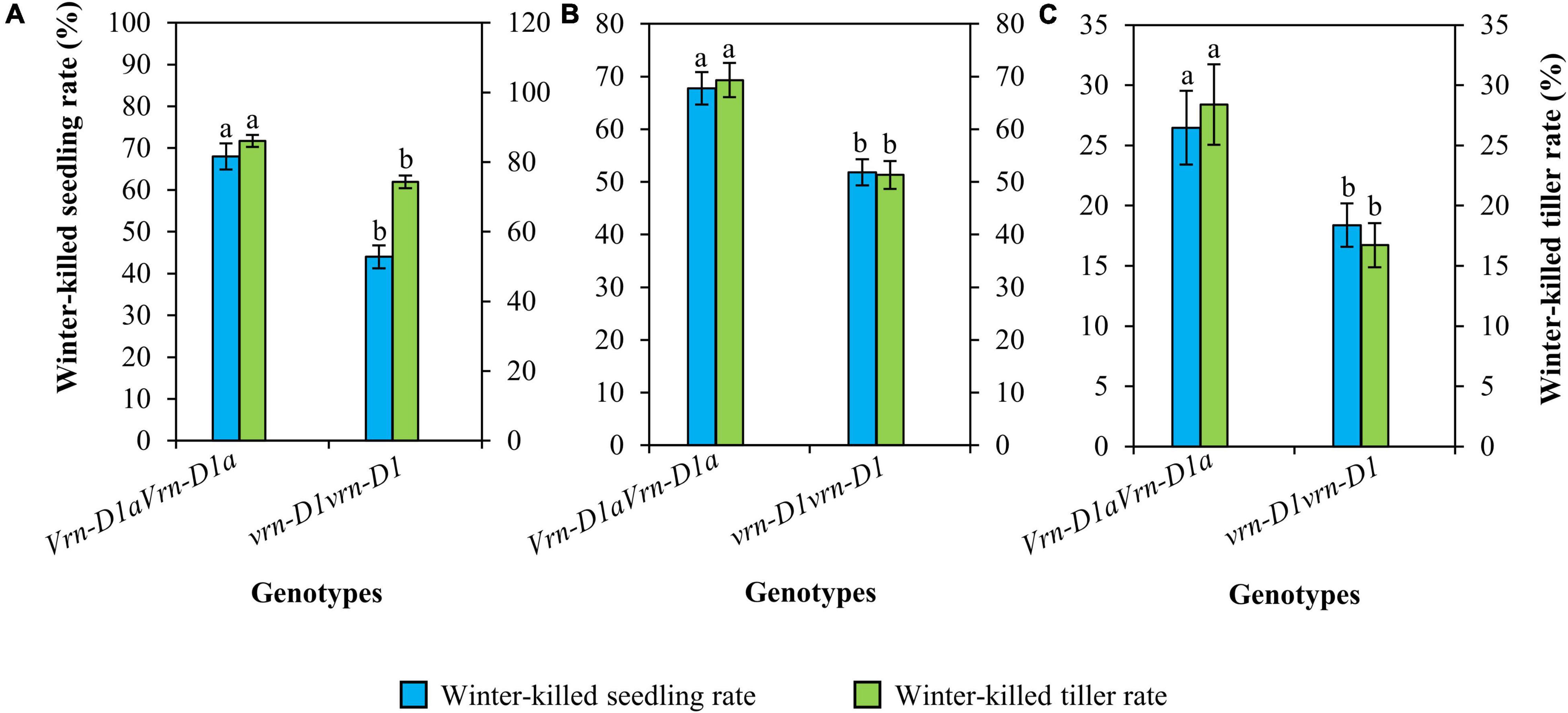

Cultivars carrying the vrn-D1vrn-D1 genotype also showed significantly lower winter-killed seedling and winter-killed tiller rates than those carrying the Vrn-D1aVrn-D1a genotype (Figure 4). Compared to the Vrn-D1aVrn-D1a genotype, the winter-killed seedling rates of the vrn-D1vrn-D1 genotype were significantly decreased by 24.0, 16.0, and 8.1%, and the winter-killed tiller rates were significantly reduced by 11.8, 18.0, and 11.7% at 2021SY (Figure 4A), 2021DX (Figure 4B), and 2021TG (Figure 4C), respectively.

Figure 4. Comparison of winter frost tolerance between genotypes vrn-D1vrn-D1 (n = 60) and Vrn-D1aVrn-D1a (n = 50) in the panel of wheat cultivars at 2021SY (A), 2021DX (B), and 2021TG (C). Differences in winter frost between genotypes for each trait were determined by the t-test and different letters above the error bars indicate a significant difference at P < 0.05.

Effect of Winter Frost on Agronomic Traits

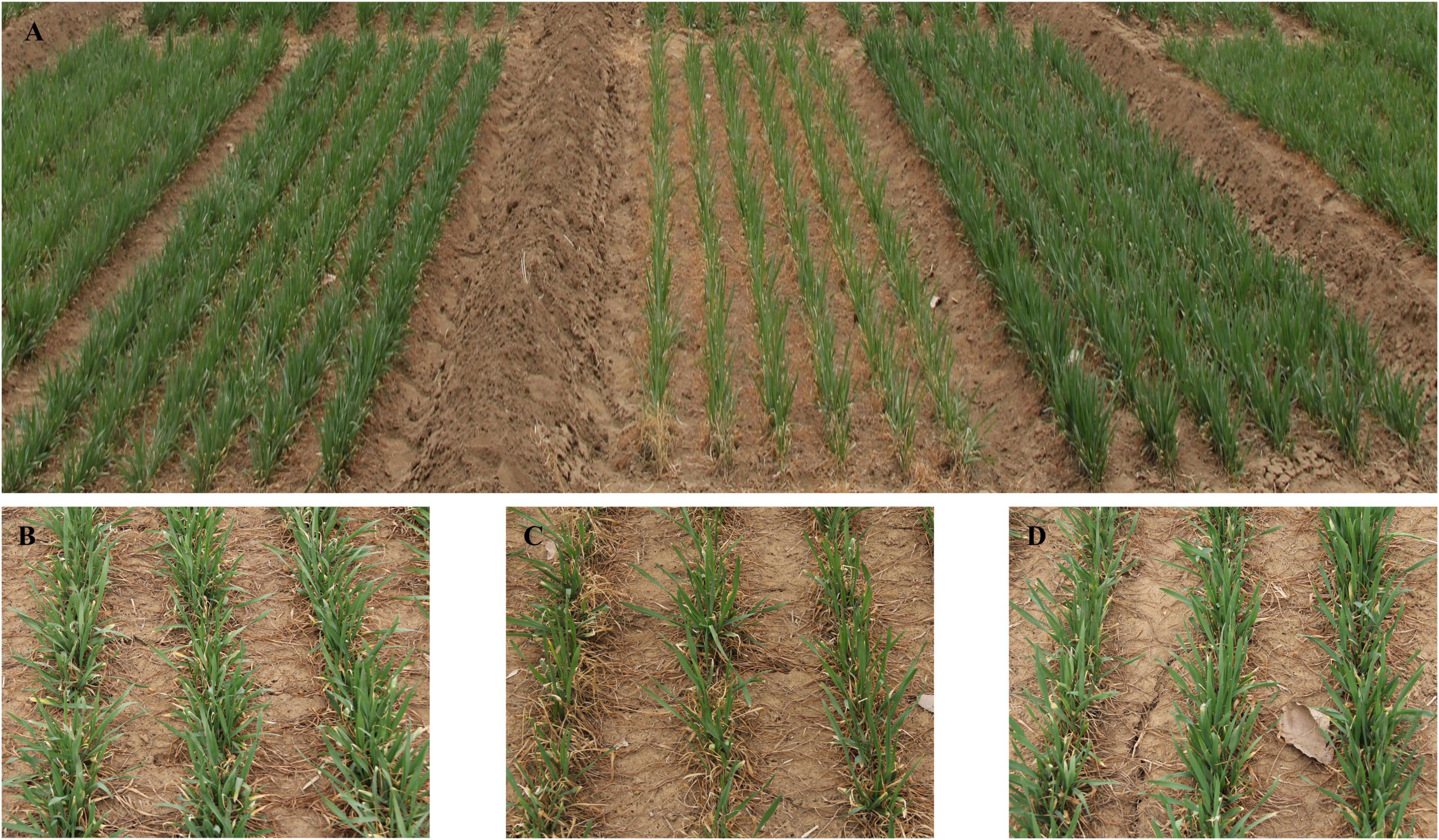

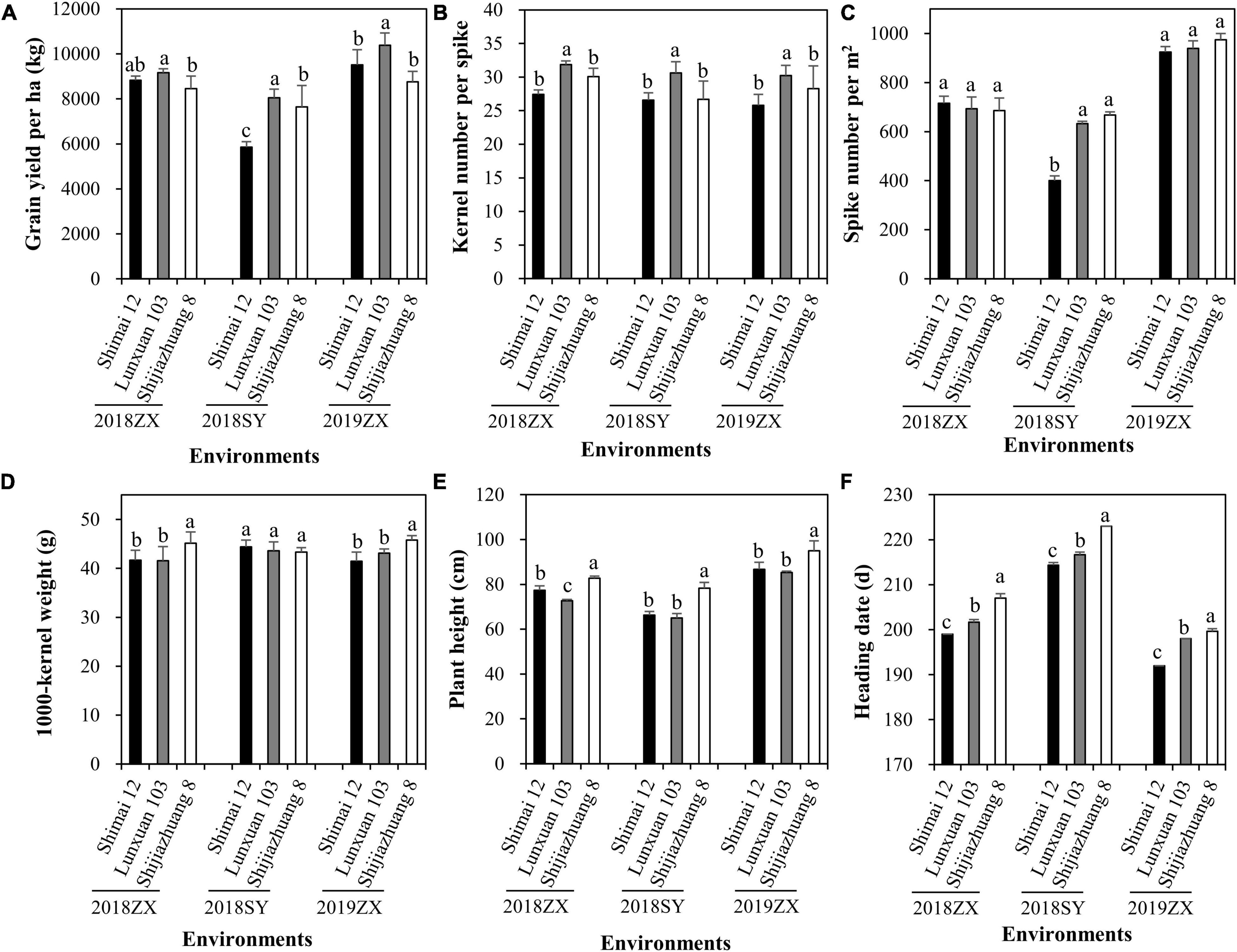

The effect of winter frost on agronomic traits was evaluated in three environments. Severe winter frost occurred in 2018SY (Figure 5). Compared to Shijiazhuang 8 and Lunxuan 103, winter frost had large effects on Shimai 12 at 2018SY, which resulted in a significant decrease in grain yield (Figure 6A) and spike number/m2 (Figure 6C) and a slight increase in kernel number per spike (Figure 6B), but no effect on the other agronomic traits (Figures 6D–E). When no winter frost or light winter frost occurred, Shimai 12 exhibited a higher grain yield than Shijiazhuang 8 at 2019ZX and 2018ZX (Figure 6A). Lunxuan 103 showed higher grain yield, more kernel number per spike (P < 0.05), shorter plant height than its parents, and an earlier heading date than Shijiazhuang 8 in all environments (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Performances of winter frost tolerance for wheat cultivar Lunxuan 103 and its parents Shijiazhuang 8 and Shimai 12 at 2018SY. (A) Plot performances of Shijiazhuang 8, Shimai 12, and Lunxuan 103 (from left to right) and partial performances of Shijiazhuang 8 (B), Shimai 12 (C), and Lunxuan 103 (D).

Figure 6. Comparison of grain yield per ha (A), kernel number per spike (B), spike number/m2 (C), 1000-kernel weight (D), plant height (E), and heading date (F) among wheat cultivar Lunxuan 103 and its parents at the three environments. Multiple comparisons were performed using the least significant difference (LSD) test and different letters above the error bars indicate significant differences among cultivars in a single environment at P < 0.05.

Expression of Vernalization Gene Vrn-D1 and Cold-Responsive Genes

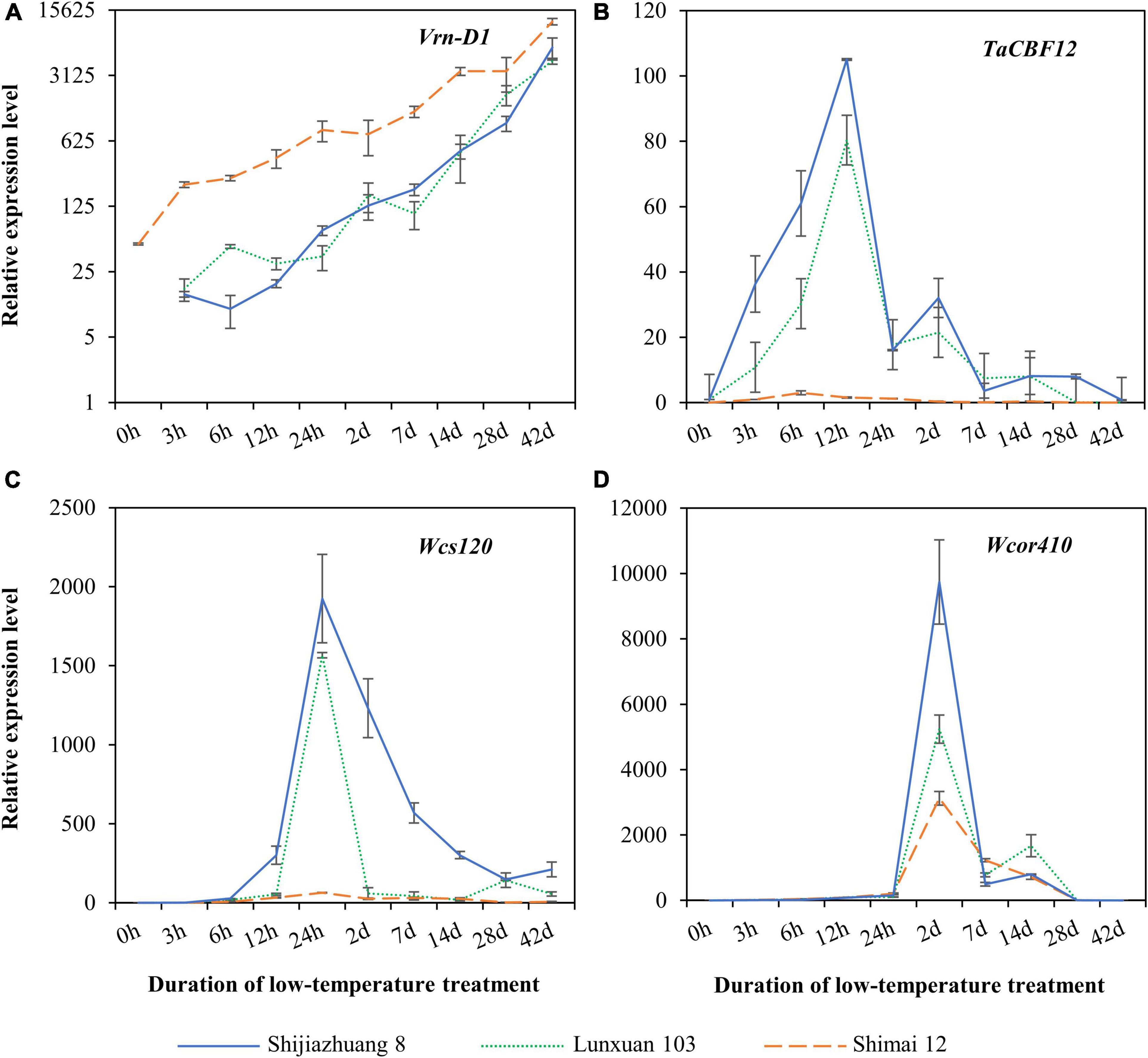

Expression patterns of the vernalization gene Vrn-D1 and the three cold-responsive genes were quantitatively compared among Lunxuan 103 and its parents, Shimai 12 and Shijiazhuang 8 (Figure 7). A dramatically different expression pattern was observed in Vrn-D1 among the three cultivars, and Shimai 12 showed significantly higher expression levels than Lunxuan 103 and Shijiazhuang 8 in all treatments (Figure 7A). Under the non-vernalization condition (0 h), the transcriptional accumulation of Vrn-D1 was observed in Shimai 12, followed by a steady increase until 42 d. Conversely, Shijiazhuang 8 and Lunxuan 103 had no Vrn-D1 expression at 0 h followed by a slow increase from 3 h to 14 d, and a sudden increase from 28 to 42 d (Figure 7A). The transcripts of the transcriptional factor gene TaCBF12 were detected at a low level in the three cultivars under the non-vernalized condition. The expression of TaCBF12 increased within 3 h after exposure of the seedlings at 4°C, peaked at 12 h, and declined thereafter (Figure 7B). A high transcript level of TaCBF12 was detected in the frost-tolerant cultivars Shijiazhuang 8 and Lunxuan 103 at 12 h, but not in the frost-sensitive cultivar Shimai 12. A similar expression pattern was observed for Wcs120, and Shijiazhuang 8 and Lunxuan 103 showed significantly higher expression levels at 24 h than Shimai 12 (Figure 7C). The cold-responsive/late-embryogenesis-abundant (Cor/Lea) gene Wcor410 was weakly expressed under the non-vernalized condition and dramatically accumulated at 2 d of low-temperature treatment in the three cultivars. Shijiazhuang 8 showed the highest transcript level of Wcor410 at 2 d, followed by Lunxuan 103, and Shimai 12 had a relatively low expression level (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. Expression analysis of vernalization gene Vrn-D1 (A) and cold-responsive genes TaCBF12 (B), Wcs120 (C), and Wcor410 (D) in Lunxuan 103 and its parents Shijiazhuang 8 and Shimai 12.

Molecular Marker and Genomic Composition Analyses of Lunxuan 103 and Its Parents

Lunxuan 103 and its parents shared the same alleles at the loci associated with plant height, vernalization, and photoperiod, except for the vernalization gene Vrn-D1 (Figure 8). At the Vrn-D1 locus, Lunxuan 103 carried the same recessive vrn-D1 allele as Shijiazhuang 8, whereas Shimai 12 contained the dominant Vrn-D1a allele.

Figure 8. Genotypic patterns of Lunxuan 103 (central panel) and its parents, Shimai 12 (the left panel) and Shijiazhuang 8 (right panel), are based on the Wheat 55K SNP array. The gray color represents the identical SNPs shared by the three genotypes. Dark red, light red, and yellow colors represent the common SNPs shared by Lunxuan 103 and Shimai 12, Lunxuan 103 and Shijiazhuang 8, and Shimai 12 and Shijiazhuang 8, respectively. Dark green, blue, and light green colors represent the unique SNPs of Shimai 12, Lunxuan 103, and Shijiazhuang 8, respectively.

Based on the Wheat 55K SNP array, a total of 43,439 high-quality SNPs were used to construct a genomic composition map using the information on the physical locations of SNPs (Figure 8). Among them, 74.4% (32,331) of SNPs were identical among the three genotypes, and 90.3% (39,209) and 81.4% (35,367) SNPs of Lunxuan 103 were common with Shimai 12 and Shijiazhuang 8, respectively. The relative genetic contributions of the two parents, Shimai 12 and Shijiazhuang 8, to Lunxuan 103 were 52.6 and 47.4%, respectively (Supplementary Table 5). In addition, 2.7% (1194) SNPs were unique to Lunxuan 103. The common SNPs shared by the three genotypes were mainly associated with binding, catalytic activity, transporter activity, structural molecule activity, and transcription factor activity (Supplementary Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 6). The unique SNPs to Lunxuan 103 were mainly associated with the developmental process and multicellular organismal process (Supplementary Figure 3), and these genes were mainly involved in 33 metabolic pathways, in which four pathways were significant for the unique genes of Lunxuan 103 (Supplementary Tables 6, 7).

Discussion

Many studies have demonstrated that the recessive vrn-1 allele is associated with frost tolerance (Sutka, 1981; Veisz and Sutka, 1989; Tóth et al., 2003; Koemel et al., 2004; Babben et al., 2018). Shimai 12 and Shijiazhuang 8 share identical alleles at known vernalization and photoperiod loci, except Vrn-D1, but differ in winter hardiness. Shijiazhuang 8 with the recessive vrn-D1 allele has a winter growth habit, whereas Shimai 12 with the dominant Vrn-D1a allele has the typical characteristic of spring cultivars (Zhang et al., 2010, 2012). We aimed to select the progenies with the homozygous vrn-D1vrn-D1 genotype at the Vrn-D1 locus during the development of Lunxuan 103. As a result, the winter frost tolerance of Lunxuan 103 was significantly improved. Based on the analysis of the relationship between the alleles at the Vrn-D1 locus and the frost tolerance in the genetic population and different wheat cultivars, it was confirmed that the recessive vrn-D1 allele can improve wheat winter frost tolerance compared to the dominant Vrn-D1a allele.

Based on the observation of spike differentiation and response to vernalization, Lunxuan 103 and Shijiazhuang 8 required 48 to 55 d more than Shimai 12 to reach the double ridge stage, and the difference was 2–5 d under vernalization for 35 d, suggesting that Lunxuan 103 and Shijiazhuang 8 have winter growth habit with strong vernalization requirement. Hence, Lunxuan 103 and Shijiazhuang 8 need a long period at a nonfreezing low temperature to meet the vernalization requirement (Dhillon et al., 2010). Vernalization is a cumulative process (Xu and Chong, 2018), which delays the wheat’s shoot apical meristem development and accumulates low-temperature tolerance until vernalization saturation (Fowler et al., 1996). This might explain that a high level of frost tolerance is observed in Lunxuan 103 and Shijiazhuang 8, but not in Shimai 12.

The frost tolerance wheat cultivars showed higher transcript levels in CBF and the COR/LEA genes than those in frost-sensitive cultivars (Motomura et al., 2013; Todorovska et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2018). Wcs120 and Wcor410 play significant roles in frost tolerance and had higher expression levels in the winter tolerant cultivars than in the sensitive spring wheat cultivars (Ganeshan et al., 2008; Motomura et al., 2013; Vítámvás et al., 2019). In the clustered CBF copies, TmCBF12 is a candidate for wheat Fr-Am2 (Knox et al., 2008). The transcript levels of Wcs120, Wcor410, and TaCBF12 were significantly higher in winter wheat cultivars Lunxuan 103 and Shijiazhuang 8 than in spring wheat cultivar Shimai 12. This finding is in agreement with the results of the previous studies (Ganeshan et al., 2008; Motomura et al., 2013). These observations suggest that the better winter frost tolerance of Lunxuan 103 is the result of an ability to maintain low-temperature-tolerance genes in an upregulated state.

The expression of vrn-1 or its induced genes can downregulate the CBF/COR genes (Linmin and Fowler, 2006; Shi et al., 2018), which inversely affected the level of frost tolerance (Kobayashi et al., 2005; Stockinger et al., 2007; Shi et al., 2018). Wheat cultivars with the dominant Vrn alleles had winter freezing tolerance than those carrying the corresponding recessive alleles (Koemel et al., 2004; Linmin and Fowler, 2006; Reddy et al., 2006). The previous study showed that a higher level of expression of Vrn-D1 was observed in the spring accessions compared to the facultative or winter ones under the non-vernalized condition (Zhang et al., 2012). It can be inferred that Shimai 12 is more sensitive to low temperature than Shijianzhuang 8, and Lunxuan 103 is attributed to its higher expression of Vrn-D1 at the vegetative stage. The improvement of freezing tolerance in Lunxuan 103 suggests that the allelic variation in the Vrn-D1 locus is sufficient to explain the differences in its freezing tolerance.

Grain yield is a high priority in most wheat breeding programs. Lunxuan 103 showed a higher grain yield than its parents regardless of the occurrence of winter frost. Based on the high-quality SNPs, the two parents contributed similar proportions of genetic loci to Lunxuan 103, suggesting that a high frequency of genetic recombination occurred in Lunxuan 103. However, Shimai 12 showed higher relative genetic contributions to Lunxuan 103 than Shijiazhuang 8 on chromosomes 3A, 4A, 5B, 6B, 1D, 2D, and 5D, whereas Shijiazhuang 8 had a higher proportion of contributions on chromosomes 3D and 6A. Previous studies have identified many QTLs associated with grain yield-related traits on the above-mentioned chromosomes. For example, the main-effect QTL QGns.cau-4A.4 controlling kernel number per spike was repeatedly identified on chromosome 4A and explained a range of phenotypic variation from 5.0 to 21.4% (Gao et al., 2015; Cui et al., 2017; Guan et al., 2018). A major QTL QYld.tam-2D for grain yield was located on chromosome 2D, with the phenotypic variation explained by 12.9–21.9% (Mason et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2018). It can be inferred that the better yield performance of Lunxuan 103 than its parents might result from gene pyramiding or interaction between the favorable loci from the two parents.

In this study, the 1194 specific SNPs to Lunxuan 103 could not be associated directly with winter frost due to the limitation of the gene annotations. However, these specific SNPs would be developed into specific markers for Lunxuan 103 for accurate identification during the commercialization of wheat breeding (Li et al., 2018).

In conclusion, the winter frost tolerance of spring wheat Shimai 12 has been significantly improved by introducing the vrn-D1 allele at the Vrn-D1 locus from winter cultivar Shijiazhuang 8, as demonstrated in the derived cultivar Lunxuan 103. Furthermore, Lunxuan 103 shows a higher grain yield potential than its parents. This study provides a successful example of improvement in winter frost tolerance by regulating vernalization responses in common wheat.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

YZ and HL designed the experiments. HZ, XX, JG, YH, XD, TL, JH, YQ, LQY, CM, HWL, and LY performed the experiments. HZ, XX, YZ, and HL analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771881), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0101000), and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of CAAS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.879768/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Breeding procedure of wheat cultivar Lunxuan 103.

Supplementary Figure 2 | Average daily maximum (A) and minimum (B) temperatures at five environments during wheat cropping seasons (from October of the first year to June of the next year).

Supplementary Figure 3 | Category analysis of the genes identified by the common SNPs (CG), specific SNPs of Shimai 12 to Lunxuan 103 (SG-SM12), specific SNPs of Shijiazhuang 8 to Lunxuan 103 (SG-SJZ8), and specific SNPs to Lunxuan 103 (SG-LX103).

Footnotes

- ^ https://www.thermofisher.cn/cn/zh/home/life-science/microarray-analysis/microarray-analysis-instruments-software-services/microarray-analysis-software.html

- ^ http://www.wheatgenome.org/

References

Babben, S., Schliephake, E., Janitza, P., Berner, T., and Keilwagen, J. (2018). Association genetics studies on frost tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) reveal new highly conserved amino substitutions in CBF-A3, CBF-A15, VRN3 and PPD1 genes. BMC Geno. 19:409. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4795-6

Case, A. J., Skinner, D. Z., Garland-Campbell, K. A., and Carter, A. H. (2014). Freezing tolerance-associated quantitative trait loci in the brundage × coda wheat recombinant inbred line population. Crop. Sci. 54, 982–992. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2013.08.0526

Cui, F., Zhang, N., Fan, X. L., Zhang, W., and Zhao, C. H. (2017). Utilization of a wheat 660K SNP array-derived high-density genetic map for high-resolution mapping of a major QTL for kernel number. Sci. Rep. 7:3788. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04028-6

Dai, L. Q., Kang, X. Y., Yao, S. R., Li, C. Q., Yu, C. W., and Wang, M. (2014). Climatic index and risk analysis of winter freezing injury for winter wheat in hebei. Chin. J. Ecol. 33, 2046–2052. doi: 10.13292/j.1000-4890.2014.0184

Dhillon, T., Pearce, S., Stockinger, E. J., Distelfeld, A., and Li, C. (2010). Regulation of freezing tolerance and flowering in temperate cereals: the VRN-1 connection. Plant Physiol. 153, 1846–1858. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.159079

Fowler, D. B., Limin, A. E., Wang, S. Y., and Ward, R. W. (1996). Relationship between low-temperature tolerance and vernalization response in wheat and rye. Can. J. Plant Sci. 76, 37–42. doi: 10.4141/cjps96-007

Fu, D., Szűcs, P., Yan, L., Helguera, M., and Skinner, J. S. (2005). Large deletions within the first intron in VRN-1 are associated with spring growth habit in barley and wheat. Mol. Genet. Geno. 273, 54–65. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1095-4

Galiba, G., Vágújfalvi, A., Li, C., Soltész, A., and Dubcovsky, J. (2009). Regulatory genes involved in the determination of frost tolerance in temperate cereals. Plant Sci. 176, 12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.09.016

Ganeshan, S., Vitamvas, P., Fowler, D. B., and Chibbar, R. N. (2008). Quantitative expression analysis of selected COR genes reveals their differential expression in leaf and crown tissues of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) during an extended low temperature acclimation regimen. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2393–2402. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern112

Gao, F. M., Wen, W. E., Liu, J. D., Rasheed, A., and Yin, G. H. (2015). Genome-wide linkage mapping of QTL for yield components, plant height and yield-related physiological traits in the Chinese wheat cross zhou 8425B/Chinese spring. Front. Plant Sci. 6:1099. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01099

Guan, P., Lu, L., Jia, L., Kabir, M. R., and Zhang, J. (2018). Global QTL analysis identifies genomic regions on chromosomes 4A and 4B harboring stable loci for yield-related traits across different environments in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 9:529. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00529

Guo, X. R., Wang, Y. Y., Meng, L. Z., Liu, H. W., and Yang, L. (2015). Distribution of the Vrn-D1b allele associated with facultative growth habit in Chinese wheat accessions. Euphytica 206, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10681-015-1440-1

Janmohammadi, M., and Mahfoozi, S. (2013). Regulatory network of gene expression during the development of frost tolerance in plants. Curr. Opin. Agric. 2, 11–19. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpx062

Kippes, N., Debernardi, J. M., Vasquez-Gross, H. A., Akpinar, B. A., and Budak, H. (2015). Identification of the VERNALIZATION 4 gene reveals the origin of spring growth habit in ancient wheats from South Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E5401–E5410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514883112

Knox, A. K., Li, C., Vágújfalvi, A., Galiba, G., and Stockinger, E. J. (2008). Identification of candidate CBF genes for the frost tolerance locus Fr-Am2 in triticum monococcum. Plant Mol. Biol. 67, 257–270.

Kobayashi, F., Takumi, S., Kume, S., Ishibashi, M., and Ohno, R. (2005). Regulation by Vrn-1/Fr-1 chromosomal intervals of CBF-mediated Cor/Lea gene expression and freezing tolerance in common wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 887–895.

Koemel, J. E., Guenzi, A. C., Anderson, J. A., and Smith, E. L. (2004). Cold hardiness of wheat near-isogenic lines differing in vernalization alleles. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109, 839–846. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1686-9

Laudencia-Chingcuanco, D., Ganeshan, S., You, F., Fowler, B., and Chibbar, R. (2011). Genome-wide gene expression analysis supports a developmental model of low temperature tolerance gene regulation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Geno. 12:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-299

Li, C., Xu, W., Guo, R., Zhang, J., and Qi, X. (2018). Molecular marker assisted breeding and genome composition analysis of Zhengmai 7698, an elite winter wheat cultivar. Sci. Rep. 8:322. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18726-8

Li, H. J., Zhou, Y., Xin, W. L., Wei, Y. Q., and Zhang, J. L. (2019). Wheat breeding in northern China: achievements and technical advances. Crop J. 7, 718–729. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2019.09.003

Li, T., Liu, H. W., Mai, C. Y., Yu, G. J., and Li, H. W. (2019). Variation in allelic frequencies at loci associated with kernel weight wand their effects on kernel weight-related traits in winter wheat. Crop J. 7, 30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2018.08.002

Linmin, A. E., and Fowler, D. B. (2006). Low-temperature tolerance and genetic potential in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): response to photoperiod vernalization, and plant development. Planta 224, 360–366. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0219-y

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Mason, R. E., Hays, D. B., Mondal, S., Ibrahim, A. M., and Basnet, B. R. (2013). QTL for yield, yield components and canopy temperature depression in wheat under late sown field conditions. Euphytica 194, 243–259. doi: 10.1007/s10681-013-0951-x

Meng, L. Z., Liu, H. W., Yang, L., Mai, C. Y., and Yu, L. Q. (2016). Effects of the Vrn-D1b allele associated with facultative growth habit on agronomic traits in common wheat. Euphytica 211, 113–122. doi: 10.1007/s10681-016-1747-6

Motomura, Y., Kobayashi, F., Iehisa, J. C. M., and Takumi, S. (2013). A major quantitative trait locus for cold-responsive gene expression is linked to frost-resistance gene Fr-A2 in common wheat. Breeding Sci. 63, 58–67. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.63.58

Muhammad, A. H., Chen, X., Muhammad, F., Noor, M., and Zhang, Y. (2021). Cold stress in wheat: plant acclimation responses and management strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 12:676884. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.676884

Reddy, L., Allan, R. E., and Garland-Campbell, K. A. (2006). Evaluation of cold hardiness in two sets of near isogenic lines of wheat (Triticum aestivum) with polymorphic vernalization alleles. Plant Breed. 125, 448–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2006.01255.x

Shi, Y., Ding, Y., and Yang, S. (2018). Molecular regulation of CBF signaling in cold acclimation. Trends Plant Sci. 23, 623–637. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2018.04.002

Snape, J. W., Sarma, R., Quarrie, S. A., Fish, L., and Galiba, G. (2001). Mapping genes for flowering time and frost tolerance in cereals using precise genetic stocks. Euphytica 120, 309–315. doi: 10.1023/A:1017541505152

Stockinger, E. J., Skinner, J. S., Gardner, K. G., Francia, E., and Pecchioni, N. (2007). Expression levels of barley Cbf genes at the frost resistance-H2 locus are dependent upon alleles at Fr-H1 and Fr-H2. Plant J. 51, 308–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03141.x

Sutka, J. (1981). Genetic studies of frost resistance in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 59, 145–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00264968

Sutka, J. (2001). Genes for frost resistance in wheat. Euphytica 119, 169–177. doi: 10.1023/A:1017520720183

Sutka, J., and Snape, J. W. (1989). Location of a gene for frost resistance on chromosome 5A of wheat. Euphytica 42, 41–44.

Todorovska, E. G., Kolev, S., Christov, N. K., Balint, A., Kocsy, G., et al. (2014). The expression of CBF genes at Fr-2 locus is associated with the level of frost tolerance in bulgarian winter wheat cultivars. Biotechnol. Biotec. Eq. 28, 392–401. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2014.944401

Tóth, B., Galiba, G., Fehér, E., Sutka, J., and Snape, J. W. (2003). Mapping genes affecting flowering time and frost resistance on chromosome 5B of wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107, 509–514. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1275-3

Veisz, O., and Sutka, J. (1989). The relationships of hardening period and the expression of frost resistance in chromosome substitution lines of wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 43, 41–45. doi: 10.1007/bf00037894

Vítámvás, P., Kosavá, K., Musilová, J., Holková, L., and Mařík, P. (2019). Relationship between dehydrin accumulation and winter survival in winter wheat and barley grown in the field. Front. Plant Sci. 10:7. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00007

Wang, L., Yang, Y. Q., Chen, L., and Hao, L. X. (2013). Impact of meteorological disaster on wheat in the central and southern hebei and prophylactic methods. Bull. Agric. Sci. Technol. 3, 168–171.

Wang, P. F., Li, G. Z., Li, G. W., Yuan, S. S., and Wang, C. Y. (2021). TaPHT1;9-4B and its transcriptional regulator TaMYB4-7D contribute to phosphate uptake and plant growth in bread wheat. New Phytol. 231, 1968–1983. doi: 10.1111/nph.17534

Wu, J. Y. (2005). Semi-dwarfing and lodging resistant winter wheat cultivar Shimai 12. Hebei Agric. Sci. Tech. 2, 14–14.

Xiao, L., Liu, L., Asseng, S., Xia, Y., and Tang, L. (2018). Estimating spring frost and its impact on yield across winter wheat in China. Agr. Forest Meteorol. 260–261, 154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2018.06.006

Xu, K., Zhao, Y., Zhao, S., Liu, H., and Wang, W. (2021). Genome-wide identification and low temperature responsive pattern of actin depolymerizing factor (ADF) gene family in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 12:618984. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.618984

Xu, S., and Chong, K. (2018). Remembering winter through vernalization. Nat. Plants 4, 997–1009. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0301-z

Xu, S., Dong, Q., Deng, M., Lin, D., and Xiao, J. (2021). The vernalization-induced long non-coding RNA VAS functions with the transcription factor TaRF2b to promote TaVRN1 expression for flowering in hexaploid wheat. Mol. Plant 14, 1525–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.05.026

Yan, L., Fu, D., Li, C., Blechl, A., and Tranquilli, G. (2006). The wheat and barley vernalization gene VRN3 is an orthologue of FT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 19581–19586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607142103

Yu, M., Mao, S. L., Hou, D. B., Chen, G. Y., and Pu, Z. E. (2018). Analysis of contributors to grain yield in wheat at the individual quantitative trait locus level. Plant Breed. 137, 35–49. doi: 10.1111/pbr.12555

Zhang, J., Wang, Y. Y., Wu, S. W., Yang, J. P., and Liu, H. W. (2012). A single nucleotide polymorphism at the Vrn-D1 promoter region in common wheat is associated with vernalization response. Theor. Appl. Genet. 125, 1697–1704.

Zhang, J., Wu, S. W., Liu, B. H., Song, M. F., and Zhou, P. (2010). Genetic improvement of wheat growth habit and its molecular marker-assisted selection in yellow and huai river reaches. Acta Agron. Sin. 36, 385–390. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2010.00385

Keywords: winter frost damage, marker-assisted selection, cold-responsive genes, grain yield, genomic composition

Citation: Zhang H, Xue X, Guo J, Huang Y, Dai X, Li T, Hu J, Qu Y, Yu L, Mai C, Liu H, Yang L, Zhou Y and Li H (2022) Association of the Recessive Allele vrn-D1 With Winter Frost Tolerance in Bread Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 13:879768. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.879768

Received: 20 February 2022; Accepted: 09 May 2022;

Published: 06 June 2022.

Edited by:

Muhammad Kashif Riaz Khan, Nuclear Institute for Agriculture and Biology, PakistanReviewed by:

Muhammad Ahmad Hassan, Anhui Agricultural University, ChinaSibum Sung, University of Texas at Austin, United States

Copyright © 2022 Zhang, Xue, Guo, Huang, Dai, Li, Hu, Qu, Yu, Mai, Liu, Yang, Zhou and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yang Zhou, emhvdXlhbmdAY2Fhcy5jbg==; Hongjie Li, bGlob25namllQGNhYXMuY24=

Hongjun Zhang1

Hongjun Zhang1 Jie Guo

Jie Guo Yiwen Huang

Yiwen Huang Jinghuang Hu

Jinghuang Hu Yunfeng Qu

Yunfeng Qu Hongjie Li

Hongjie Li