- 1Biomedicine College, Beijing City University, Beijing, China

- 2State Key Laboratory for Quality Ensurance and Sustainable Use of Dao-di Herbs, Institute of Medicinal Plant Development, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

- 3Guangxi Crop Genetic Improvement and Biotechnology Lab, Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Nanning, Guangxi, China

- 4Yuelushan Laboratory, Changsha, Hunan, China

DNA methylation and demethylation play a crucial role in plant development, fruit ripening, and the accumulation of secondary metabolites. It is primarily catalyzed and regulated by cytosine-5 DNA methyltransferases (C5-MTases) and DNA demethylases (dMTases). In our study, six C5-MTase and four dMTase genes were identified in Siraitia grosvenorii genome. Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that the six SgC5-MTase were divided into four categories, SgMET1, SgCMTs, SgDRMs, and SgDNMT2. The four SgdMTase were grouped into SgROS1, SgDML3, SgDME subfamilies. Transcript abundance levels of SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes revealed changes during vegetative and reproductive development. Furthermore, the expression of SgdMTase genes was upregulated during fruit ripening, while SgCMT2/3 genes were downregulated. This indicates a potential rise in demethylation, aligning with the accumulation pattern of mogroside V. Our results suggest a role for DNA methylation modifications in the growth, development, maturation, and accumulation of mogrosides, which will also facilitate future epigenetic studies in S. grosvenorii.

1 Introduction

DNA methylation is a pivotal epigenetic modification involving the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of a cytosine residue to form 5-methylcytosine (Finnegan et al., 2000; Cao et al., 2014). This modification does not alter the DNA sequence but can profoundly influence gene transcription activity by modulating chromatin architecture, recruiting specific binding proteins, or interfering with transcription factor binding. Consequently, it leads to phenotypic variation without genotypic change and serves as a core regulatory mechanism in numerous biological processes, such as regulating gene expression (Cui et al., 2016), maintaining genome stability (Li et al., 2015), facilitating genomic imprinting (Choi et al., 2002), coordinating developmental and physiological processes (Huang et al., 2019), and mediating environmental stress responses (Bharti et al., 2015). in plants.

In plants, DNA methylation occurs in the symmetrical CG and CHG (where H represents A, T, or C) contexts, as well as the asymmetrical CHH context. mCG and mCHG contexts are maintained by methyltransferase 1 (MET1) and chromomethylases 2/3 (CMT2/3), respectively, while mCHH contexts are sustained by a combination of CMT2 and domain rearranged methyltransferase 2 (DRM2) (Ma et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018). DRM2 is crucial for de novo methylation through the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway, acting across both symmetric and asymmetric contexts. DNA methylation plays a critical role in regulating a wide range of biological processes. This dynamic methylation network is further precisely counterbalanced by active DNA demethylation executed by DNA demethylases (dMTases), including Demeter (DME), Repressor of Silencing 1 (ROS1), and Demeter-like Proteins 2 (DML2) and 3 (DML3) (Zhu, 2009)., together constituting a core epigenetic regulatory system that enables plants to adapt to developmental cues and environmental changes.

This sophisticated machinery is extensively involved in myriad biological processes, including leaf development, flowering time, fruit ripening, and seed development. leaf growth (Candaele et al., 2014), flowering time ( (Bai et al., 2021)), fruit ripening (Zhong et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015), seed development (Xing et al., 2015), and hybrid vigor (Kawanabe et al., 2016). Accumulating evidence has highlighted its critical role in regulating plant secondary metabolism. DNA methylation can directly or indirectly modulate the expression of key enzyme genes in the biosynthetic pathways of important secondary metabolites—such as alkaloids, flavonoids, and terpenoids—by altering chromatin states, thereby influencing the accumulation of these high-value compounds (Zhang et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2022). For instance, in taxane biosynthesis, a CHH-type hypermethylation hotspot within the core promoter of the BAPT gene was identified as a Y-patch element, whose methylation level is significantly negatively correlated with taxane accumulation (Pandey and Pandey Rai, 2015).

Siraitia grosvenorii (monk fruit or luohanguo), a unique medicinal and edible plant indigenous to China, derives its characteristic sweetness and health benefits primarily from mogrosides, a group of triterpenoid saponins (Wu et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2018). As the most important secondary metabolites in S. grosvenorii, the biosynthesis and accumulation of mogrosides are undoubtedly under precise spatiotemporal control by internal developmental programs and external environmental factors. DNA methylation, acting as a bridge integrating these signals, likely plays a crucial yet unexplored regulatory role. Although the C5-MTase and dMTase gene families have been identified and preliminarily characterized in several model and crop plants, such as Arabidopsis thaliana (Zhang et al., 2018; Ashapkin et al., 2016), Solanum lycopersicum (Guo et al., 2020; Lang et al., 2017), Citrus sinensis (Huang et al., 2019), Fragaria x ananassa (Cheng et al., 2018), Salvia miltiorrhiza (Li et al., 2018), Oryza sativa (Ahmad et al., 2014), Sorghum bicolor (Vafadarshamasbi et al., 2022), Zea may (Candaele et al., 2014), and Dendrobium officinale (Yu et al., 2021). However, their functions in S. grosvenorii growth, development, and particularly in mogroside accumulation, remain entirely unknown.

Therefore, to elucidate the potential functions of DNA methylation and demethylation mechanisms in S. grosvenorii, this study presents the first genome-wide identification and comprehensive analysis of the C5-MTase and dMTase gene families. We systematically characterized their phylogenetic relationships, gene structures, protein-protein interaction networks, and promoter cis-acting elements. Furthermore, we investigated their expression profiles across various tissues (roots, stems, leaves, flowers) and during different fruit developmental stages to explore potential correlations with plant development and mogroside accumulation. Our findings provide a foundational resource for understanding the epigenetic regulation of mogroside biosynthesis and offer novel candidate genes and strategies for the epigenetic improvement of S. grosvenorii fruit quality.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material

S. grosvenorii (Cultivar Qingpiguo) were grown at the Yongfu County cultivation base (Guilin, China, GPS coordinates are E110.030835 and N24.9637). Roots, young stems, stems, young leaves, leaves, male flowers (bloom day), female flowers (bloom day), fruits at 5 days after pollination (DAP), fruits at 35 DAP, fruits at 65 DAP were harvested. Each sample contained three biological replicates, the collected samples were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C before use.

2.2 Data collection and identification of SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes in S. grosvenorii

The Arabidopsis C5-MTase protein sequence, obtained from the Phytozome database (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html), was used as the reference sequence. The S. grosvenorii genome data will be published separately. The Hidden Markov Model (HMM) for the DNA-methylase domain (PF00145) was downloaded from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/), along with HMMs for the helix-hairpin-helix, Gly/Pro-rich loop (HhH-GPD, PF00730) and RNA recognition motif demethylase (RRM-DME, PF15628) as reference models (Yu et al., 2021). The HMMER 3.0 search tool was used to identify C5-MTase and dMTase proteins in S. grosvenorii (E-value ≤ 1e−10) (Wheeler and Eddy, 2013). Redundant sequences and incomplete proteins lacking key domains (PF00145, PF00730, PF15628) were manually removed. The conserved domains of SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase family members were verified using the Conserved Domain Database (NCBI-CDD, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd). The amino acid composition, molecular weight (Mw), and theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of the protein sequences were analyzed using the EXPASY tool (http://web.expasy.org/protparam). Subcellular localization of the C5-MTase and dMTase genes was predicted using Plant-mPLoc (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/plant-multi/).

2.3 Phylogenetic tree construction

To investigate the classification of C5-MTase and dMTase genes, sequences from 14 plant species were retrieved, representing various plant categories: typical dicots (Arabidopsis thaliana and Solanum lycopersicum), medicinal dicots (Salvia miltiorrhiza, Ricinus communis, and Chrysanthemum nankingense), typical Cucurbitaceae species (Cucumis sativus, Momordica charantia, Cucumis melo, Citrullus lanatus, and Cucurbita moschata), typical monocots (Sorghum bicolor, Oryza sativa, and Zea mays), and medicinal monocots (Dendrobium officinale) (Supplementary Tables S1, S2). These sequences were obtained from the NCBI Protein Database and CuGenDBv2 (http://cucurbitgenomics.org/v2/). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using Maximum Likelihood (ML) method in MEGA 11 (Yang, 2007), based on 119 aligned protein sequences with Poisson correction and 1000 bootstrap replicates. Tree visualization was performed using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) online tool (Letunic and Bork, 2021).

2.4 Conserved motif and gene structure analysis

Conserved motifs of all SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase proteins were analyzed using the MEME Suite (v5.05) program (http://meme-suite.org) (Bailey et al., 2006). Gene structure analysis was performed using the Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS, https://gsds.gao-lab.org/) (Hu et al., 2015). The 2000-bp upstream sequences of SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes were extracted from the Sg genome, and cis-acting regulatory elements were predicted using the PlantCARE tool (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) (Lescot, 2002). Protein-protein interaction networks were constructed using the STRING 11 tool (https://string-db.org).

2.5 Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from three biological replicates per tissue using Ve Zol Reagent R411 (Vazyme, Beijing, China), with each replicate representing an independent plant. RNA integrity was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and RNA concentration was quantified using a NanoDrop 2000C Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using TransScript One-step DNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis Super Mix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). qRT-PCR primers (Supplementary Table S3) were designed using Primer Premier 6. qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate on a CFX96™ real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ (Vazyme, Beijing, China). SgUBQ (Shi et al., 2019) was used as the internal control, and relative mRNA levels were calculated using the 2^−ΔΔCt method. Results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Differential expression among tissues was analyzed by one-way ANOVA using IBM SPSS 25 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

3 Result

3.1 Identification and structural analysis of SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes in S. grosvenorii

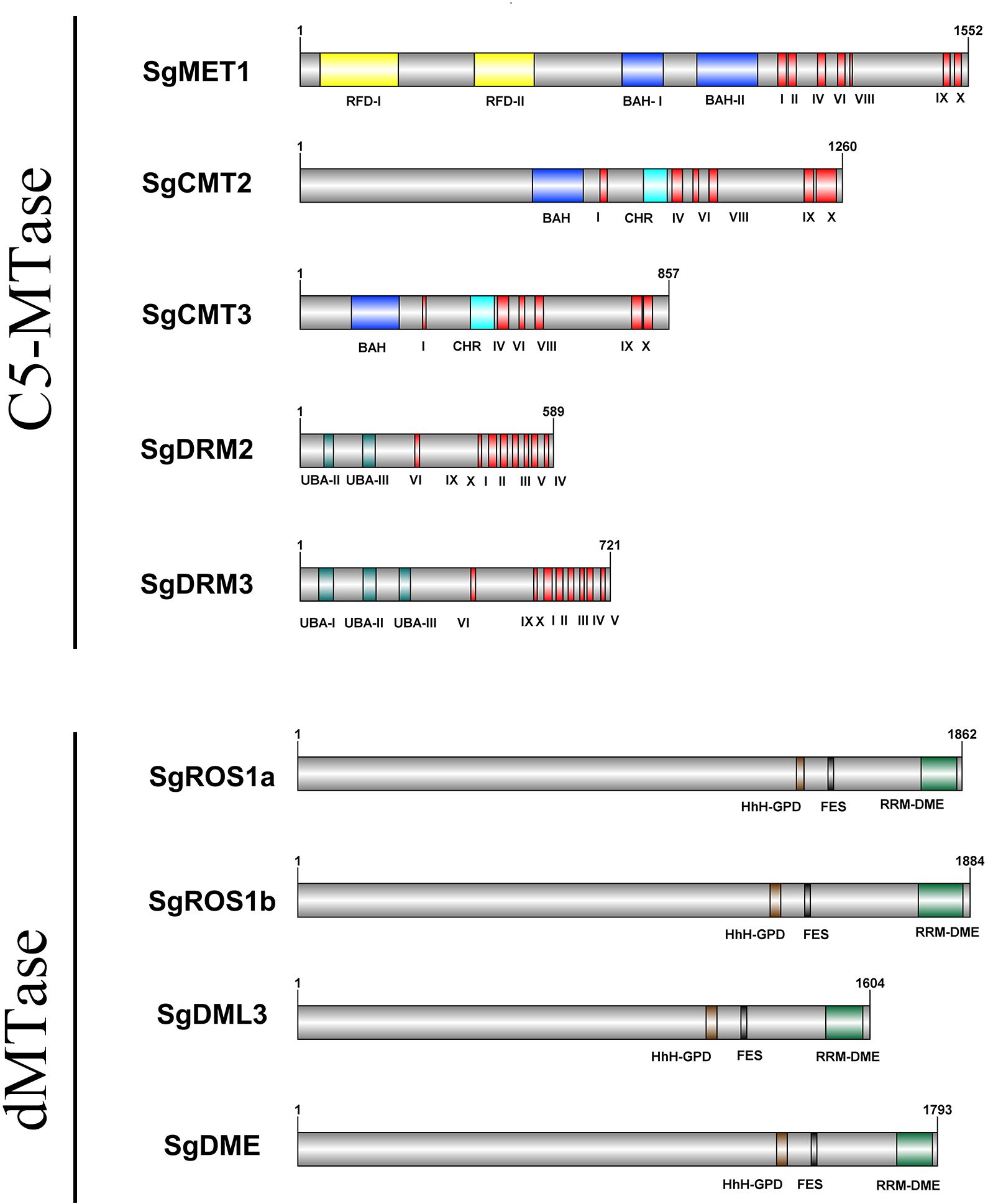

A total of six SgC5-MTase genes were identified in the S. grosvenorii genome. These genes encoded proteins with conserved C-terminal catalytic domains, yet they exhibit diverse N-terminal domain combinations. Proteins containing two replication foci domains (RFD) and two bromo adjacent homology (BAH) domains at the N-terminus were classified as members of the MET family. Proteins with a BAH domain and a chromo (CHR) domain belonged to the CMT family, while those with a ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain at the N-terminus are categorized within the DRM family. Proteins lacking N-terminal domains were classified as DNMT2 family members. Accordingly, the six genes were named SgMET1, SgCMT2, SgCMT3, SgDRM2, SgDRM3, and SgDNMT2 (Figure 1; Table 1; Supplementary Figures S1, S2, S3, S4, S1, S2).

Four SgdMTase genes were identified in S. grosvenorii, all of which belonged to the DME-like family. These genes encoded proteins that universally contain the HhH-GPD, FES, and RRM-DME domains at the C-terminus. Therefore, the four genes were designated as SgDME1, SgDML3, SgROS1a, and SgROS1b (Figure 1, Table 1).

The polypeptide lengths of the identified six SgC5-MTase genes (SgMET1, SgCMT2, SgCMT3, SgDRM2, SgDRM3, SgDNMT2) ranged from 383 to 1552 amino acids, with predicted molecular weights ranging from 44.00 to 175.34 kDa and theoretical isoelectric points (pI) from 4.82 to 8.52. While the four SgdMTase genes (SgROS1a, SgROS1b, SgDML3, SgDME) encoded polypeptides that range from 1664 to 1884 amino acids in length, with molecular weights between 180.64 and 211.16 kDa, and theoretical pI values ranging from 5.81 to 8.86 (Table 1).

3.2 Motif and domain analysis of SgC5-MTases and SgdMTases in S. grosvenorii

To gain further insights into the conservation and diversity of SgC5-MTases and SgdMTases in S. grosvenorii, their protein motifs were examined using MEME. (E ≤ 0.01) (Supplementary Table S4). A total of 15 conserved motifs, ranging from 21 to 50 amino acids in length, were detected. Each C5-MTase protein contains 2 to 15 motifs. Motifs 3, 5, 7, and 15 were highly conserved in the DRM subfamily, while motifs 1 and 7 were characteristic of the DNMT2 subfamily. Motifs 1~7, 11 and 14 were predominantly located in the C-terminal region, representing the main conserved motifs in the CMT and MET subfamilies, with motif 11 within the BAH-I domain. Motifs 8, 9, 13were exclusive to the N-terminal region of the MET subfamily, with motif 8 found within the RFD-I domain, motif 13 within the RFD-II domain, and motif 9 within the BAH-II domain (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic relationships, conserved motifs, and gene structures of C5-MTase (A) and dMTase (B) gene families in A thaliana and S. grosvenorii.

Similarly, conserved motifs within the dMTase protein sequences of S. grosvenorii i and A. thaliana were analyzed using MEME (E ≤ 0.01) (Supplementary Table S5). A total of 15 conserved motifs, ranging from 17 to 50 amino acids, were identified. Each dMTase protein contains 11 to 15 motifs. Motifs 1~5, 7, 8, and 11~14 were highly conserved across all dMTases. Motifs 1, 3~8, and 11~14 were primarily located in the C-terminal region, with motifs 4 and 5 situated within the RRM-DME domain (Figure 2B).

3.3 Phylogenetic analysis of SgC5-MTases and SgdMTases in S. grosvenorii and other plant species

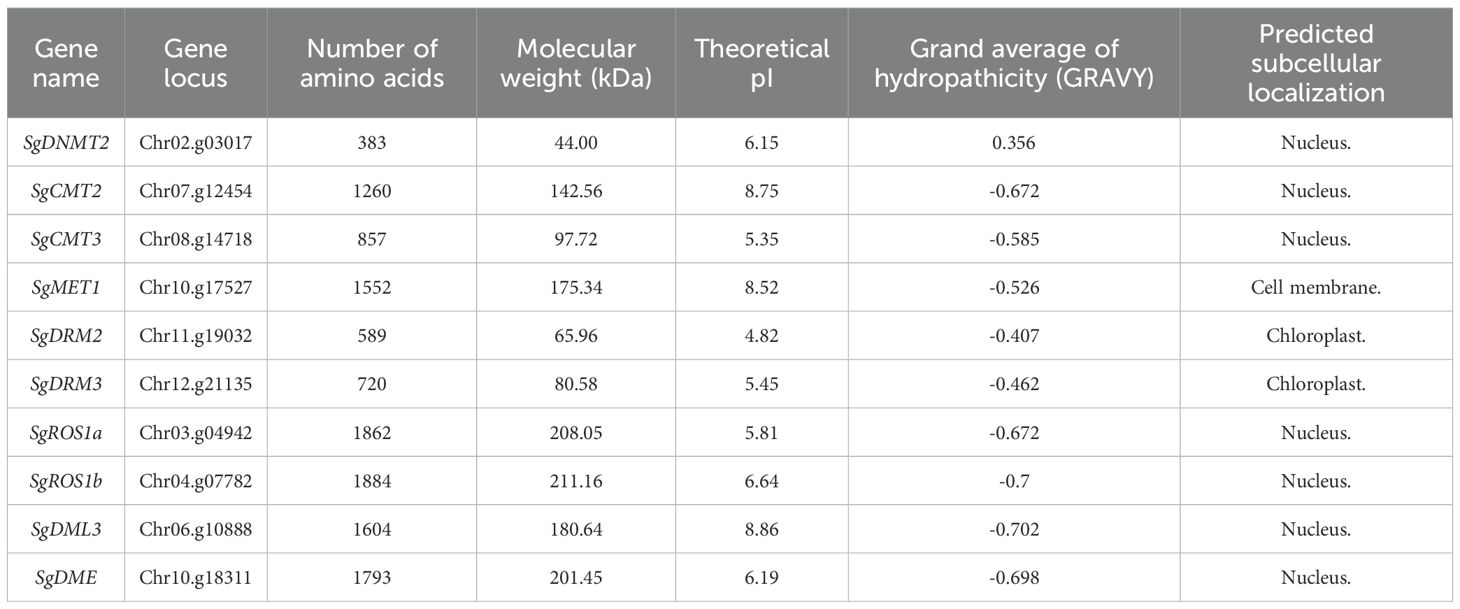

To investigate the evolutionary relationships of SgC5-MTase, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using 107 C5-MTase protein sequences (Figure 3A). The tree revealed that C5-MTase proteins from the 14 species clustered into four distinct groups: DRM, CMT, MET, and DNMT, with 33, 39, 21, and 14 members, respectively. This classification is consistent with previous studies in other plants (Qian et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2014), confirming the domain-based classification and nomenclature. The MET subfamily was further divided into dicot and monocot groups, while DRM was split into DRM2 and DRM3 clades, each further subdivided into dicot and monocot groups. Similarly, CMT was divided into CMT2 and CMT1/3 clades, with both subdivided into dicot and monocot groups. In contrast, the DNMT2 subfamily showed no clear distinction between monocots and dicots. Overall, each of the MET and DNMT2 subfamilies contained a SgC5-MTase, while the CMT and DRM subfamilies each had two SgC5-MTases. SgC5-MTases exhibited close phylogenetic relationships with C5-MTases from other Cucurbitaceae species, which is consistent with their taxonomic placement. For the dMTase proteins, 60 sequences clustered into three orthologous groups: ROS1, DML3, and DME, with 11, 21, and 28 members, respectively (Figure 3B). The ROS1 and DML3 groups were further divided into monocot and dicot subgroups, while the DME group was exclusive to dicots, suggesting that DME was monophyletic within dicots, consistent with prior studies. In summary, the DME and DML3 subfamilies each contained one SgdMTase, while the ROS1 subfamily included two SgdMTases. SgdMTases manifested close phylogenetic relationships with those of other Cucurbitaceae species, implying evolutionary conservation of function.

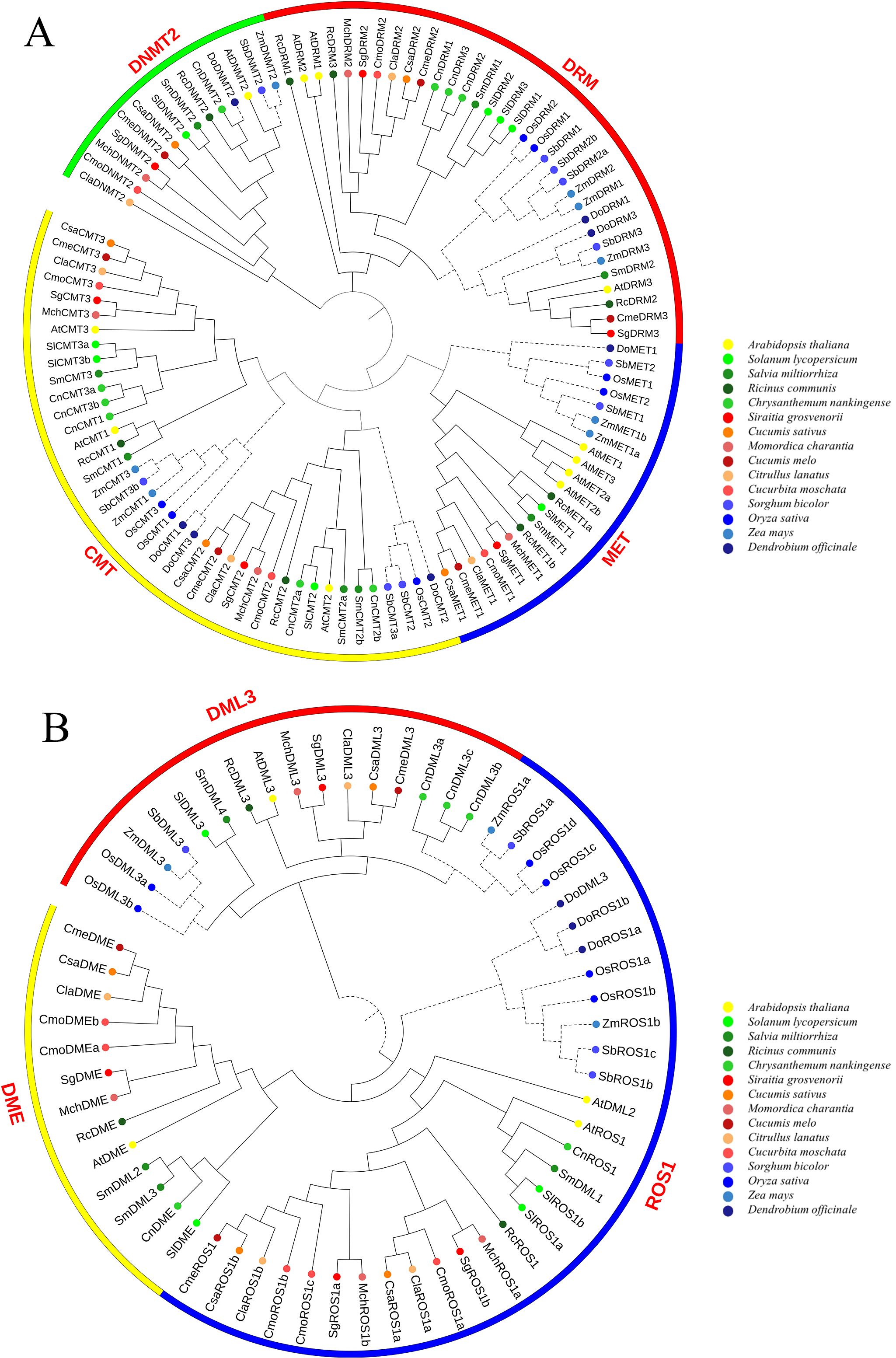

3.4 Predicted protein-protein interaction of SgC5-MTases and SgdMTases

A protein-protein interaction network for SgC5-MTases and SgdMTases was constructed using the STRING 12 tool, based on homologous proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana. The PPI network revealed that SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase proteins align closely with their respective A. thaliana orthologs (Figure 4). SgDNMT2 exhibited 66.1% identity with AtDNMT2, while SgMET1 shared 59.6% identity with AtMET1. SgCMT2 and SgCMT3 were highly homologous to AtCMT2 and AtCMT3, with 59.1% and 58.2% identity, respectively. Additionally, SgDRM2 and SgDRM3 showed 56.3% and 40.3% homology with AtDRM2 and AtDRM3. SgROS1a and SgROS1b shared 44.4% and 45.4% homology with AtROS1, while SgDML3 and SgDME exhibited 49.1% and 53.8% homology with AtDME and AtDML3, respectively.

Figure 4. Computational prediction of protein-protein interaction network for SgC5-MTases and SgdMTases showing functional and physical associations among proteins. The dotted lines represented a relatively weak interaction while the solid lines indicated a relatively strong interaction. Colored lines between the proteins indicated the various types of interaction evidence: blue line indicated curated databases, yellow line indicated textmining evidence, black line indicated co-expression evidence and purple line indicated experimental evidence.

The interaction among SgMET1, SgCMT2 and SgDRM2 was observed, then SgROS1a, SgROS1b, SgDML3, SgDME and SgCMT3 were clustered, and the third cluster was formed only by SgDNMT2 (Figure 4). A confidence score of 0.70 for interactions between SgMET1, SgCMT2, and SgDRM2 suggested that these proteins may regulate global DNA methylation levels through protein–protein interactions or by forming complexes. SgDML3 interacted primarily with SgC5-MTases, especially SgCMTs and SgDRMs, indicating a dynamic relationship between SgC5-MTases and SgdMTases in regulating overall DNA methylation. This suggested a reciprocal negative feedback loop between SgC5-MTases and SgdMTases that modulated methylation levels.

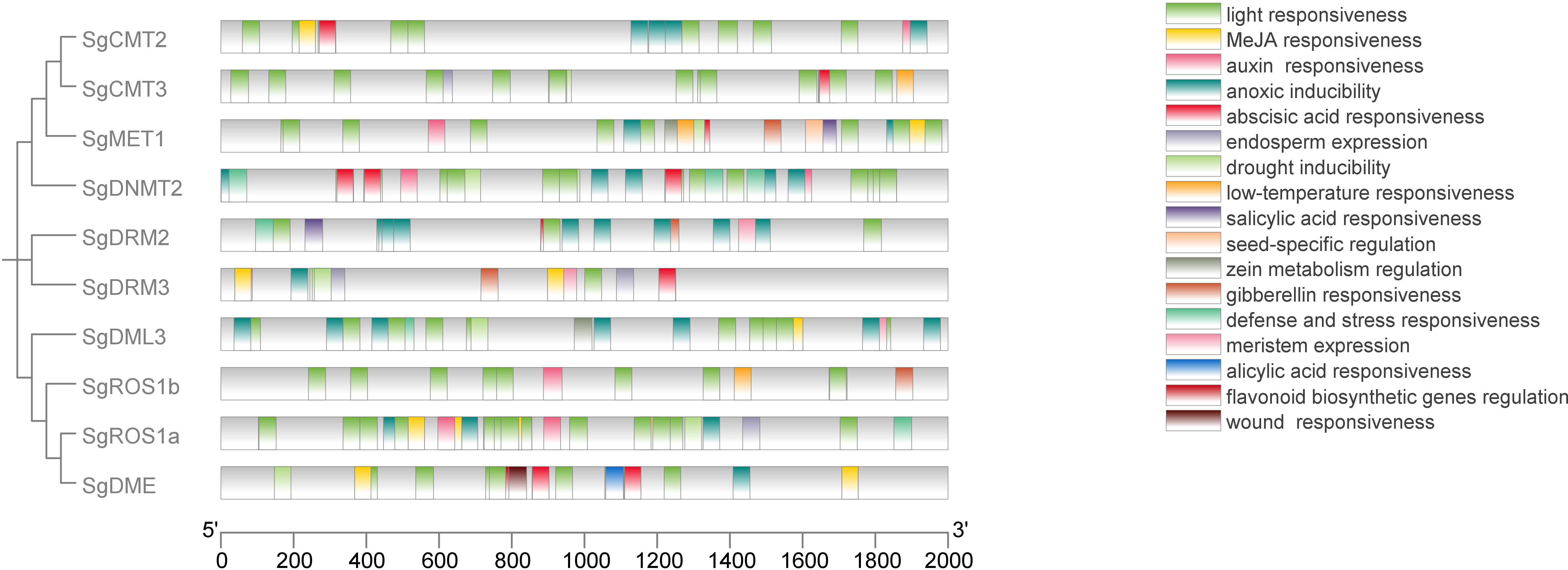

3.5 Cis-acting elements analysis in SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes

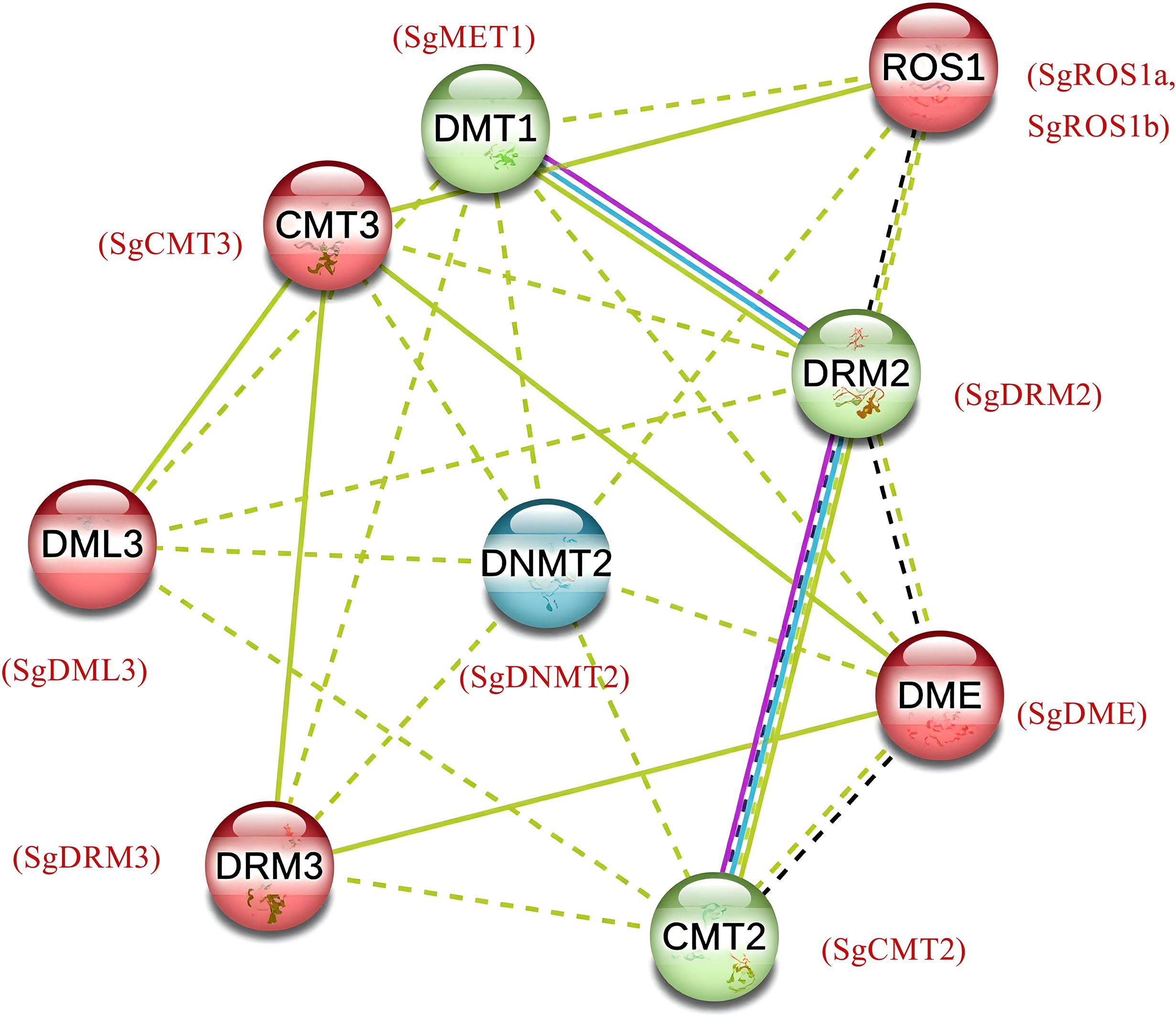

Cis-elements involved in hormone response, light response, stress response, and tissue specificity were identified in the 2000-bp upstream regulatory regions of the SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes using the PlantCARE database (Figure 5; Supplementary Table S6). Tissue-specific elements (6/248) were found, predominantly in the endosperm (4/6) and seed (2/6). Hormone-responsive elements (71/248) were identified, including those responsive to methyl jasmonate (MeJA) (28/71), abscisic acid (ABA) (25/71), auxin (9/71), gibberellin (GA) (5/71), and salicylic acid (SA) (4/71). Additionally, a substantial number of stress-related elements (164/248) were observed, including those responsive to anoxia (32/164), drought (10/164), low temperature (3/164), light (112/164), stress (6/164), and wounding (1/164). Furthermore, bioanabolic-responsive elements (7/248) were identified, such as those involved in alicyclic acid (1/7), meristem expression (3/7), zein metabolism regulation (2/7), and flavonoid biosynthesis regulation (1/7). These results indicated that the SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes may play significant roles in responding to hormones and light stress in S. grosvenorii.

Figure 5. Prediction of cis-elements in the 2000-bp upstream regulatory regions of SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes. Different cis-responsive elements are represented by different colored boxes.

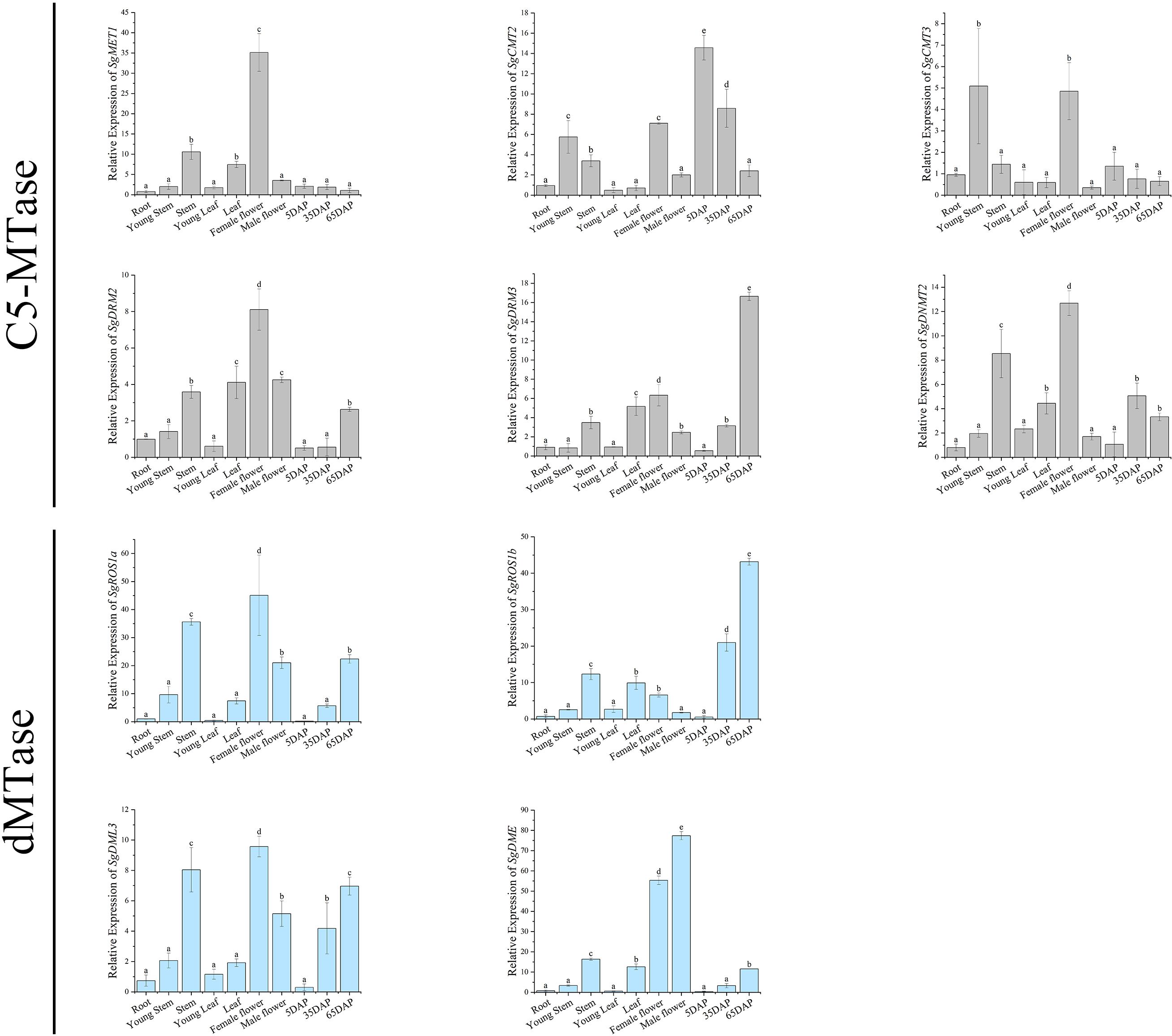

3.6 Transcript abundance analysis of SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes

To explore their potential roles in plant growth and development, we analyzed the expression patterns of SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes across different tissues and three fruit ripening stages (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Relative expression levels of SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes in different tissues. (* indicates P<0.05, ** indicates P<0.01).

The expression of SgMET1 was higher in stems, leaves, and female flowers, but it was relatively low in fruits. SgCMT2/3 were highly expressed in young stems, stems, female flowers, and young fruits, with a significant down-regulation observed in later-stage fruits. In contrast, the expression of SgDRM2/3 was more prominent in stems, leaves, flowers, and later-stage fruits than in early developmental stages, suggesting up-regulation during plant growth and fruit ripening.

The expression of all SgdMTase genes, similar to DRM2/3, was higher in mature tissues than in young tissues. SgROS1b expression was markedly elevated in late-stage fruits relative to other tissues, indicating a fruit-specific expression pattern. Additionally, SgDME was highly expressed in female and male flowers, approximately 55 and 77 times higher than in roots, respectively, and much higher than in other tissues. Previous studies in A.thaliana have shown that DME activated the expression of maternal FIS2, FWA, and MEA alleles, playing a key role in endosperm imprinting and seed viability (Choi et al., 2002). DME-mediated DNA demethylation also occurred in male gamete companion cells and coincides with the down-regulation of DDM1 (Zhang et al., 2018). These findings suggested that SgDME may play a crucial role in the formation and development of male and female gametes in S. grosvenorii.

4 Discussion

S. grosvenorii, a perennial vine in the Cucurbitaceae family, is rich in fatty acids, essential amino acids, flavonoids, and triterpenoids. Among these, mogrosides, a class of intensely sweet non-sugar compounds of triterpenoid secondary metabolites, have significant potential for use in food additives, functional foods, and traditional Chinese medicine (Matsumoto et al., 2009). Despite its importance, the biosynthesis and regulation of mogrosides remain only partially understood, and their content is strongly influenced by environmental and developmental factors (Qiao et al., 2019). Recent studies have highlighted that epigenetic modifications, particularly DNA methylation, play pivotal roles in modulating plant development and secondary metabolism in response to external cues (Yuan et al., 2015). However, knowledge of methylation-related enzymes in S. grosvenorii is limited. To address this gap, we systematically identified the SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes across the genome, and performed an integrative analysis of their conserved motifs, phylogenetic relationships, protein-protein interactions, cis-acting elements, and transcript abundance.

DNA methylation is crucial for plant growth, with C5-MTases and dMTases playing roles in various biological processes (La et al., 2011; Ono et al., 2012). For instance, the DRM1, DRM2, CMT3 triple mutant exhibited dwarfism, partial sterility, and slow growth in A.thaliana (Cao and Jacobsen, 2002). C5-MTases and dMTases also significantly impact fruit ripening. Changes in the expression levels of C5-MTase and dMTase genes during the ripening process have been detected in species such as kiwifruit (Zhang et al., 2020), eggplant (Moglia et al., 2019), and grape (Shangguan et al., 2020). Active demethylation by the SlDML2 was essential for tomato fruit ripening, with loss of function mutants failing to ripen (Lang et al., 2017). Similarly, strawberry exhibited DNA hypomethylation during ripening, with FvDRM1.3, FvDRM3.1 and genes involved in RNA-directed DNA methylation being downregulated (Cheng et al., 2018). In contrast, the process of orange fruit ripening was accompanied by a decrease in the expression of CsdMTase genes, correlating with increased DNA methylation levels (Huang et al., 2019). SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes, similar to those in Salvia miltiorrhiza, were generally expressed at higher levels in flowers compared to other tissues (Li et al., 2018). What’s more, SgdMTase genes expression increased during plant growth and fruit ripening, while SgCMT2/3 genes expression decreased. SgMET1 expression in fruits declined, but not significantly. It was noteworthy that the expression levels of de novo methyltransferases SgDRM2/SgDRM3 genes were higher in mature tissues and fruits than in young tissues and fruits, suggesting that new methylation was continuously established during plant growth and development. MET and CMT are primarily responsible for maintaining CG and CHG methylation, respectively, while DRM is involved in de novo methylation, mainly targeting CHH methylation (Zang et al., 2023). Our results indicated that DNA methylation in S. grosvenorii was a dynamic and complementary process. Our findings suggest that DNA methylation in S. grosvenorii is a dynamic and complementary process. Nevertheless, changes in the transcript levels of SgC5-MTases and SgdMTases across developmental stages are not sufficient to infer actual alterations in enzyme activity or the global methylation landscape. Future studies should incorporate stage-specific whole-genome bisulfite sequencing in combination with transcriptome analyses to establish the causal relationships between methylation dynamics and developmental transitions.

DNA methylation can regulate the accumulation of secondary metabolites in plants. DNA methylation modulates gene expression by influencing the binding of transcriptional activators and repressors to promoter regions of key enzymes (Elhamamsy, 2016). The expression of phenylalanine ammonia lyase (AaPAL1) inn Artemisia annua, a key enzyme in flavonoid biosynthesis, was epigenetically controlled by site-specific demethylation at transcription factor binding sites (AaMYB1, AaMYC, AaWRKY) in its promoter region (Pandey et al., 2019). Mogroside V, a key component of mogrosides, is a high-sweetness, low-calorie, naturally derived non-sugar sweetener that has received Generally Recognized As Safe certification from the U.S. FDA (Marone et al., 2008). Currently, it has been approved for use in over 20 countries, highlighting its promising application potential (Cui et al., 2023). The content of mogroside V remains extremely low within the first 30 DAP but increases sharply after 50 DAP (Tang et al., 2011). We noticed that the accumulation of mogroside V showed the same trend as the expression of all SgdMTase genes, but an opposite trend to that of the methyltransferases SgCMT2/3 genes. The increased expression of SgdMTase genes and the decreased expression of SgCMT2/3 genes may potentially reduce the methylation level in the promoter regions of key enzymes in the mogroside V synthesis pathway, facilitating the binding of transcriptional activators to these regions and thereby enhancing gene expression. To further validate these hypotheses, future studies could perform overexpression or knockout experiments of SgC5-MTases (e.g., SgCMT2/3) or SgdMTases (e.g., SgROS1b) to identify key mogroside biosynthetic genes regulated by DNA methylation. Additionally, targeted epigenetic editing approaches, such as dCas9-TET or dCas9-DNMT (Hu et al., 2021), could be employed to investigate the effects of site-specific methylation changes in candidate biosynthetic genes on both their expression and the accumulation of mogrosides. These approaches will be essential to move from correlative observations to mechanistic understanding and may provide a foundation for metabolic improvement in S. grosvenorii.

Evidence increasingly supports the involvement of C5-MTase and dMTase genes in abiotic stress responses (Ganguly et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2018). Cis-acting elements, as molecular switches, regulate stress-inducible gene expression and various biological processes (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 2005). In this study, a significant number of hormone-responsive, light-responsive, and stress-responsive cis-acting elements were identified in the promoter regions of SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes, with notable abundance in light-responsive, hormone-responsive, and drought stress-responsive elements. Among the hormone-responsive elements identified, those responsive to MeJA were the most abundant, accounting for 39.4% of all hormone-responsive elements. Previous studies have demonstrated that MeJA treatment can significantly enhance the expression of key enzyme genes involved in mogroside biosynthesis in S. grosvenorii (Zhang, 2016). Based on these findings, we hypothesize that MeJA may regulate the expression of SgC5-MTases and SgdMTases, thereby influencing the methylation status of promoter regions of mogroside biosynthetic genes and ultimately modulating their transcription. Consequently, future studies could employ MeJA treatment experiments to systematically evaluate its effects on SgC5-MTases and SgdMTases expression as well as mogroside accumulation.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we systematically identified and characterized six SgC5-MTases and four SgdMTases in S. grosvenorii, and elucidated their evolutionary relationships, structural features, and expression profiles. Phylogenetic analysis categorized the six SgC5-MTases into four groups: SgCMT, SgDRM, SgMET1, and SgDNMT2, while the four SgdMTases were classified into the SgROS1, SgDML3, and SgDME subfamilies. For the first time, our results demonstrate that SgC5-MTase and SgdMTase genes display complementary expression dynamics during fruit development, which closely correspond to the accumulation pattern of mogroside V. This provides novel genome-wide evidence for a potential link between DNA methylation-related enzymes and mogroside biosynthesis. Our findings not only expand the fundamental understanding of epigenetic regulation in S. grosvenorii, but also lay a foundation for future studies on the molecular mechanisms by which DNA methylation regulates mogroside biosynthesis. Such insights offer potential applications in molecular breeding and the metabolic improvement of this medicinal plant.

Data availability statement

All relevant data is contained within the article: The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

YZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft. CW: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. JS: Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LX: Resources, Writing – review & editing. CM: Resources, Writing – review & editing. ZL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. XM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7252244); Guangxi Key R&D Program (GuiKe AB25069119); Yuelushan Laboratory Breeding Program (YLS-2025-ZY04058); The National Natural Science Foundation of China (82104548; U20A2004); CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2021-I2M-1-071).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1567781/full#supplementary-material

References

Ahmad, F., Huang, X., Lan, H. X., Huma, T., Bao, Y. M., Huang, J, et al. (2014). Comprehensive gene expression analysis of the DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferase family in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genet. Mol. Res. 13, 5159–5172. doi: 10.4238/2014.July.7.9

Ashapkin, V. V., Kutueva, L. I., and Vanyushin, B. F. (2016). Plant DNA methyltransferase genes: Multiplicity, expression, methylation patterns. Biochem. (Moscow) 81, 141–151. doi: 10.1134/S0006297916020085

Bai, M. J., Liu, J. Y., Fan, C. G., Chen, Y. Q., Chen, H., Lu, J., et al. (2021). KSN heterozygosity is associated with continuous flowering of Rosa rugosa Purple branch. Horticulture Res. 8, 26. doi: 10.1038/s41438-021-00464-8

Bailey, T. L., Williams, N., Misleh, C., and Li, W. W. (2006). MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W369–W373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl198

Bharti, P., Mahajan, M., Vishwakarma, A. K., Bhardwaj, J., and Yadav, S. K. (2015). AtROS1 overexpression provides evidence for epigenetic regulation of genes encoding enzymes of flavonoid biosynthesis and antioxidant pathways during salt stress in transgenic tobacco. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 5959–5969. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv304

Candaele, J., Demuynck, K., Mosoti, D., Beemster, G. T. S., Inzé, D., and Nelissen, H.. (2014). Differential methylation during maize leaf growth targets developmentally regulated genes. Plant Physiol. 164, 1350–1364. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.233312

Cao, X. and Jacobsen, S. E. (2002). Role of the Arabidopsis DRM methyltransferases in de novo DNA methylation and gene silencing. Curr. Biol. 12, 1138–1144. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00925-9

Cao, D. Y., Ju, Z., Gao, C., Mei, X. H., Fu, D. Q., Zhu, H. L., et al. (2014). Genome-wide identification of cytosine-5 DNA methyltransferases and demethylases in Solanum lycopersicum. Gene 550, 230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.08.034

Cheng, J. F., Niu, Q. F., Zhang, B., Chen, K. S., Yang, R. H., Zhu, J. K., et al. (2018). Downregulation of RdDM during strawberry fruit ripening. Genome Biol. 19, 212. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1587-x

Choi, Y., Gehring, M., Johnson, L., Hannon, M., Harada, J. J., Goldberg, R. B., et al. (2002). Demeter, a DNA glycosylase domain protein, is required for endosperm gene imprinting and seed viability in. Arabidopsis. Cell 110, 33–42. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00807-3

Cui, X., Lu, F. L., Qiu, Q., Zhou, B., Gu, L. F., Zhang, S. B., et al. (2016). REF6 recognizes a specific DNA sequence to demethylate H3K27me3 and regulate organ boundary formation in Arabidopsis. Nat. Genet. 48, 694–699. doi: 10.1038/ng.3556

Cui, S. R., Zang, Y. M., Xie, L., Mo, C. M., Su, J. X., Jia, X. L., et al. (2023). Post-ripening and key glycosyltransferase catalysis to promote sweet mogrosides accumulation of siraitia grosvenorii fruits. Molecules 28, 4697. doi: 10.3390/molecules28124697

Elhamamsy, A. R. (2016). DNA methylation dynamics in plants and mammals: overview of regulation and dysregulation: DNA methylation dynamics in plants and mammals. Cell Biochem. Funct. 34, 289–298. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3183

Finnegan, E. J., Peacock, W. J., and Dennis, E. S. (2000). DNA methylation, a key regulator of plant development and other processes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10, 217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00061-7

Ganguly, D. R., Crisp, P. A., Eichten, S. R., and Pogson, B. J. (2017). The Arabidopsis DNA methylome is stable under transgenerational drought stress. Plant Physiol. 175, 1893–1912. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.00744

Guo, X. H., Xie, Q., Li, B. Y., and Su, H. Z. (2020). Molecular characterization and transcription analysis of DNA methyltransferase genes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Genet. Mol. Biol. 43, e20180295. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-gmb-2018-0295

Hu, B., Jin, J. P., Guo, A. Y., Zhang, H., Luo, J. C., and Gao, G. (2015). GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 31, 1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817

Hu, D. H., Yu, Y. M., Wang, C., Long, Y. P., Liu, Y., Feng, L., et al. (2021). Multiplex CRISPR-Cas9 editing of DNA methyltransferases in rice uncovers a class of non-CG methylation specific for GC-rich regions. Plant Cell 33, 2950–2964. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab162

Huang, H., Liu, R., Niu, Q., Tang, K., Zhang, B., Zhang, H., et al. (2019). Global increase in DNA methylation during orange fruit development and ripening. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 1430–1436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1815441116

Kawanabe, T., Ishikura, S., Miyaji, N., Sasaki, T., Wu, L. M., Itabashi, E., et al. (2016). Role of DNA methylation in hybrid vigor in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113 (43), E6704–E6711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613372113

La, H. G., Ding, B., Mishra, G. P., Zhou, B., Yang, H. M., Bellizzia, M. R., et al. (2011). A 5-methylcytosine DNA glycosylase/lyase demethylates the retrotransposon Tos17 and promotes its transposition in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 15498–15503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112704108

Lang, Z. B., Wang, Y. H., Tang, K., Tang, D. G., Datsenka, T., Cheng, J. F., et al. (2017). Critical roles of DNA demethylation in the activation of ripening-induced genes and inhibition of ripening-repressed genes in tomato fruit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, (22). doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705233114

Lescot, M. (2002). PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325

Letunic, I. and Bork, P. (2021). Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W293–W296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab301

Li, Q., Gent, J. I., Zynda, G., Song, J., Makarevitch, I., Hirsch, C. D., et al. (2015). RNA-directed DNA methylation enforces boundaries between heterochromatin and euchromatin in the maize genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 14728–14733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514680112

Li, J., Li, C., and Lu, S. (2018). Identification and characterization of the cytosine-5 DNA methyltransferase gene family in Salvia miltiorrhiza. PeerJ 6, e4461. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4461

Liu, C., Dai, L. H., Liu, Y. P., Dou, D. Q., Sun, Y. X., Ma, L. Q., et al. (2018). Pharmacological activities of mogrosides. Future Medicinal Chem. 10, 845–850. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2017-0255

Liu, R. L., How-Kit, A., Stammitti, L., Teyssier, E., Rolina, D., Mortain-Bertrand, A., et al. (2015). A DEMETER-like DNA demethylase governs tomato fruit ripening. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 10804–10809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503362112

Livak, K. J. and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using Real-Time quantitative PCR and the 2–ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Ma, L., Hatlen, A., Kelly, L. J., Becher, H., Wang, W. C., Kovarik, A., et al. (2015). Angiosperms are unique among land plant lineages in the occurrence of key genes in the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway. Genome Biol. Evol. 7, 2648–2662. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv171

Ma, Y. Z., Min, L., Wang, M. J., Wang, C. Z., Zhao, Y. L., Li, Y. Y., et al. (2018). Disrupted genome methylation in response to high temperature has distinct affects on microspore abortion and anther indehiscence. Plant Cell 30, 1387–1403. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00074

Marone, P. A., Borzelleca, J. F., Merkel, D., Heimbach, J. T., and Kennepohl, E. (2008). Twenty eight-day dietary toxicity study of Luo Han fruit concentrate in Hsd: SD® rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 46, 910–919. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.10.013

Matsumoto, S., Jin, M. L., Dewa, Y., Nishimura, J., Moto, M., Murata, Y., et al. (2009). Suppressive effect of Siraitia grosvenorii extract on dicyclanil-promoted hepatocellular proliferative lesions in male mice. J. Toxicological Sci. 34, 109–118. doi: 10.2131/jts.34.109

Moglia, A., Gianoglio, S., Acquadro, A., Valentino, D., Milani, A. M., Lanteri, S., et al. (2019). Identification of DNA methyltransferases and demethylases in Solanum melongena L., and their transcription dynamics during fruit development and after salt and drought stresses. PloS One 14, e0223581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223581

Ono, A., Yamaguchi, K., Fukada-Tanaka, S., Terada, R., Mitsui, T., and Iida, S.. (2012). A null mutation of ROS1a for DNA demethylation in rice is not transmittable to progeny. Plant J. 71, 564–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05009.x

Pandey, N., Goswami, N., Tripathi, D., Kumar Rai, K., Kumar Rai, S., Singh, S., et al. (2019). Epigenetic control of UV-B-induced flavonoid accumulation in Artemisia annua L. Planta 249, 497–514. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-3022-7

Pandey, N., Goswami, N., Tripathi, D., Rai, K. K., Rai, S. K., Singh, S., et al. (2015). Deciphering UV-B-induced variation in DNA methylation pattern and its influence on regulation of DBR2 expression in. Artemisia annua L. Planta 242, 869–879. doi: 10.1007/s00425-015-2323-3

Qian, Y. X., Xi, Y. L., Cheng, B. J., and Zhu, S. W. (2014). Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of DNA methyltransferase gene family in maize. Plant Cell Rep. 33, 1661–1672. doi: 10.1007/s00299-014-1645-0

Qiao, J., Luo, Z. L., Gu, Z., Zhang, Y. L., Zhang, X. D., Ma, X. J., et al. (2019). Identification of a novel specific cucurbitadienol synthase allele in Siraitia grosvenorii correlates with high catalytic efficiency. Molecules 24, 627. doi: 10.3390/molecules24030627

Shangguan, L. F., Fang, X., Jia, H. F., Chen, M. X., Zhang, K. K., and Fang, J. G.. (2020). Characterization of DNA methylation variations during fruit development and ripening of Vitis vinifera (cv. ‘Fujiminori’). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 26, 617–637. doi: 10.1007/s12298-020-00759-5

Shi, H. W., Liao, J. J., Cui, S. R., Luo, Z. L., and Ma, X. J. (2019). Effects of forchlorfenuron on the morphology, metabolite accumulation, and transcriptional responses of. Siraitia grosvenorii fruit. Molecules 24, 4076. doi: 10.3390/molecules24224076

Tang, Q., Ma, X. J., Mo, C. M., Wilson, I. W., Song, C., Zhao, H., et al. (2011). An efficient approach to finding Siraitia grosvenorii triterpene biosynthetic genes by RNA-seq and digital gene expression analysis. BMC Genomics 12, 343. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-343

Vafadarshamasbi, U., Mace, E., Jordan, D., and Crisp, P. A. (2022). Decoding the sorghum methylome: understanding epigenetic contributions to agronomic traits. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 50, 583–596. doi: 10.1042/BST20210908

Wei, C. Y., Li, M. T., Cao, X. M., Jin, Z. N., Zhang, C., Xu, M., et al. (2022). Linalool synthesis related PpTPS1 and PpTPS3 are activated by transcription factor PpERF61 whose expression is associated with DNA methylation during peach fruit ripening. Plant Sci. 317, 111200. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111200

Wheeler, T. J. and Eddy, S. R. (2013). nhmmer: DNA homology search with profile HMMs. Bioinformatics 29, 2487–2489. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt403

Wu, J. J., Jian, Y. Q., Wang, H. Z., Huang, H. X., Gong, L. M., Liu, G. G., et al. (2022). A review of the phytochemistry and pharmacology of the fruit of siraitia grosvenorii (Swingle): A traditional chinese medicinal food. Molecules 27, 6618. doi: 10.3390/molecules27196618

Xing, M. Q., Zhang, Y. J., Zhou, S. R., Hu, W. Y., Wu, X. T., Ye, Y. J., et al. (2015). Global analysis reveals the crucial roles of DNA methylation during rice seed development. Plant Physiol. 168, 1417–1432. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00414

Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. and Shinozaki, K. (2005). Organization of cis-acting regulatory elements in osmotic- and cold-stress-responsive promoters. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.012

Yang, Z. (2007). PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088

Yu, Z. M., Zhang, G. H., Teixeira da Silva, J. A., Li, M. Z., Zhao, C. H., He, C. M., et al. (2021). Genome-wide identification and analysis of DNA methyltransferase and demethylase gene families in Dendrobium officinale reveal their potential functions in polysaccharide accumulation. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 21. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02811-8

Yuan, Y., Wei, Y., Yu, J., and Huang, L. Q. (2015). Relationship of epigenetic and Dao-di herbs. China J. Chin. Materia Med. 40, 2679–2683. doi: 10.4268/cjcmm20151335

Zang, Y. M., Xie, L., Su, J. X., Luo, Z. L., Jia, X. L., and Ma, X. J. (2023). Advances in DNA methylation and demethylation in medicinal plants: a review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50, 7783–7796. doi: 10.1007/s11033-023-08618-8

Zhang, K. (2016). The effects of methyl jasmonate on the biosynthetic pathway of mogrosides and the preliminary screening of bHLH transcription factors in Siraitia grosvenorii fruits. (Beijing: Peking Union Medical College).

Zhang, Y. X., He, X. Q., Zhao, H. C., Xu, W. C., Wang, H., Wang, S. Y., et al. (2020). Genome-wide identification of DNA methylases and demethylases in Kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis). Front. Plant Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.514993

Zhang, H., Lang, Z., and Zhu, J. (2018). Dynamics and function of DNA methylation in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 489–506. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0016-z

Zhong, S. L., Fei, Z. J., Chen, Y. R., Zheng, Y., Huang, M. Y., Vrebalov, J., et al. (2013). Single-base resolution methylomes of tomato fruit development reveal epigenome modifications associated with ripening. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 154–159. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2462

Keywords: Siraitia grosvenorii, C5-MTase, dMTase, fruits, gene expression

Citation: Zang Y, Wang C, Su J, Xie L, Mo C, Luo Z and Ma X (2025) Genome-wide identification and characterization of DNA methyltransferases and demethylases in Siraitia grosvenorii. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1567781. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1567781

Received: 28 January 2025; Accepted: 03 October 2025;

Published: 05 December 2025.

Edited by:

Yogeshwar Vikram Dhar, Ruhr University Bochum, GermanyReviewed by:

Katia Scortecci, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, BrazilJi Jiao-jiao, Shanxi Medical University, China

Copyright © 2025 Zang, Wang, Su, Xie, Mo, Luo and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zuliang Luo, enVsaWFuZ2x1b0AxNjMuY29t; Xiaojun Ma, eGptYUBpbXBsYWQuYWMuY24=

Yimei Zang

Yimei Zang Chongnan Wang2

Chongnan Wang2 Lei Xie

Lei Xie Changming Mo

Changming Mo