- 1Jiangxi Engineering Laboratory for the Development and Utilization of Agricultural Microbial Resources, College of Bioscience and Bioengineering, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang, China

- 2Research Center of Plant Functional Genes and Tissue Culture Technology, College of Bioscience and Bioengineering, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang, China

- 3Jiangxi Province Key Laboratory of Vegetable Cultivation and Utilization, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang, China

1 Introduction

Leaf senescence, the orchestrated degradation of cellular and tissue components that precipitates aging and eventual death, represents an adaptive mechanism allowing plants to efficiently reallocate resources and respond to fluctuating environmental conditions (Woo et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2021; Ahmad et al., 2024). The onset of senescence is marked by chlorophyll degradation, leading to leaf yellowing, a process driven by extensive metabolic reprogramming at various stages of senescence (Woo et al., 2019). Plants have developed intricate signaling networks to sense senescence-related cues, including abiotic and biotic stressors, age, and developmental signals. Consequently, an array of regulatory pathways, encompassing epigenetic modifications, (post) transcriptional, and (post) translational regulations, are activated (Woo et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). Senescence-associated genes (SAGs) serve as pivotal key hubs in transmitting senescence signals, and their expression and function are regulated by multiple transcription factor (TF) families, such as WRKYs and NACs (Bengoa Luoni et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2023; Ahmad et al., 2024). However, the precise molecular mechanism underlying leaf senescence is still largely unexplored.

Phytohormones are pivotal in modulating leaf senescence and can be categorized into senescence promoters and retardants (Jibran et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2021; Asim et al., 2023). Besides these well-established roles of phytohormones, small signaling peptides have emerged as indispensable regulators in various aspects of plant developmental and adaptive processes (Xie et al., 2022; Ji et al., 2025; Xiao et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). Typically composed of fewer than 100 amino acids, small signaling peptides are usually synthesized in the cytoplasm as prepropeptides, and they undergo processing or post-translational modifications in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus. Subsequently, they are transported to the apoplast, where they execute their physiological functions (Olsson et al., 2019). Then apoplast localized small signaling peptides are usually recognized by their specific membrane-bound receptors or co-receptors that usually belongs to the leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinases (LRR-RLKs) family (Ji et al., 2025; Xiao et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). The peptide-receptor module orchestrates either long-distance or local signaling cascades, thereby modulating developmental and adaptive responses through multiple regulatory mechanisms, including (post) transcriptional, (post) translational, and epigenetic modifications (Ji et al., 2025; Xiao et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). Research has demonstrated that small signaling peptides from Arabidopsis thaliana such as CLAVATA3/EMBRYO-SURROUNDING REGION-RELATED (CLE) (Han et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b), SERINE-RICH ENDOGENOUS PEPTIDE (SCOOPs) (Zhang et al., 2024a), PHYTOSULFOKINE (PSK) (Yamakawa et al., 1999; Matsubayashi et al., 2006; Komori et al., 2009), and INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION-LIKE6 (IDL6) (Guo et al., 2022) are integral in managing leaf senescence by modulating distinct signaling pathways, thereby providing novel mechanistic insights into the regulation of leaf senescence.

2 CLE peptides delay leaf senescence via ethylene and ROS pathways

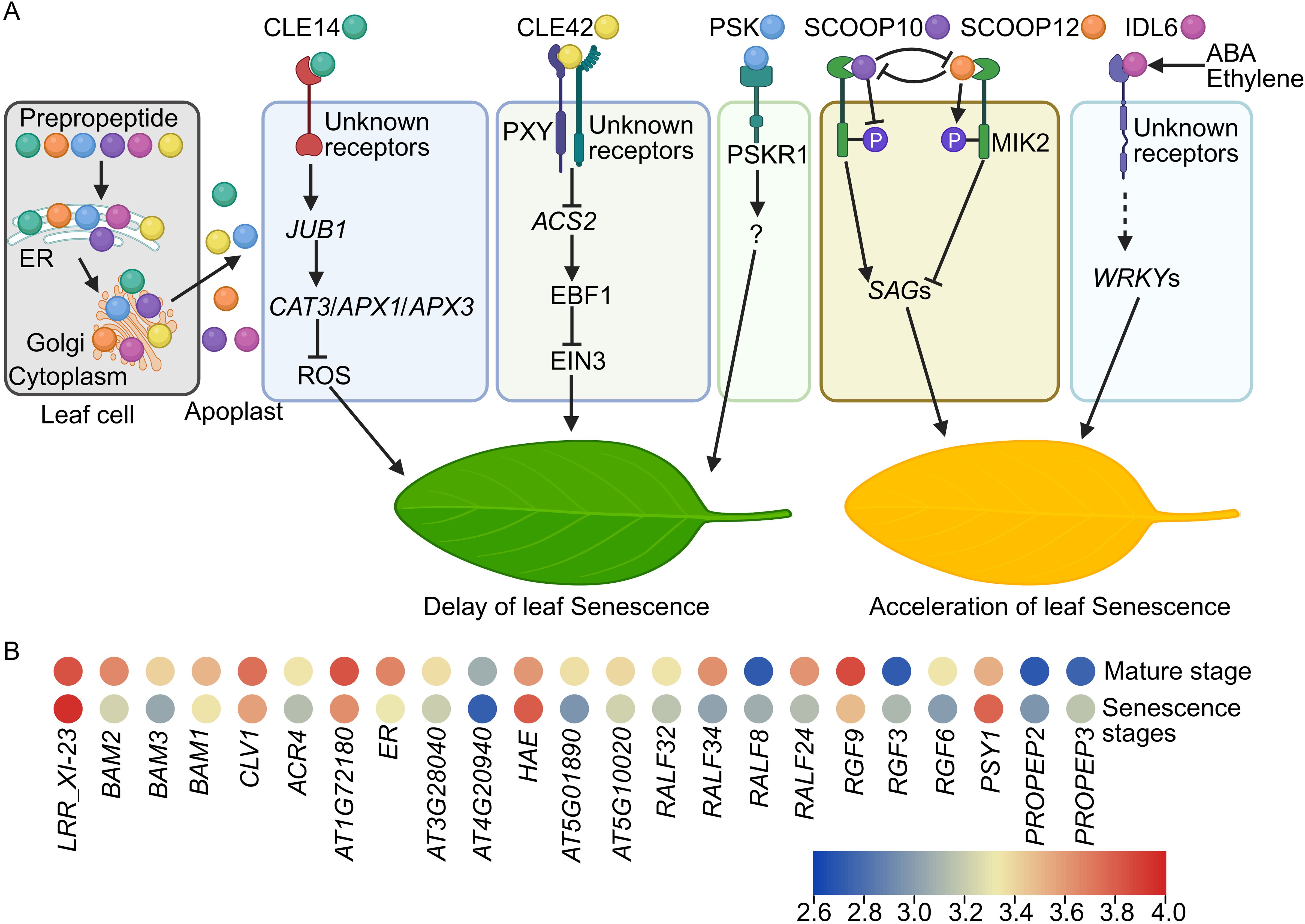

CLE proteins generally possess an N-terminal signal sequence that guides them into the secretory pathway, a central variable domain, and one or multiple conserved CLE motifs at the C-terminus, which are typically post-translationally modified to produce functional polypeptides (Fletcher, 2020; Xie et al., 2022). Transcriptomic analyses indicate differential expression of CLE genes in mature and senescent leaves, implying their involvement in leaf senescence (Lyu et al., 2019; Han et al., 2022). Specifically, CLE14 and CLE42 peptides are crucial in delaying leaf senescence (Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b). The expression level of CLE14 and CLE42 is induced by multiple senescence clues, such as salinity, drought, and darkness (Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b). Mutants deficient in CLE14 or CLE42 gene function exhibit early leaf senescence, whereas transgenic plants overexpressing CLE14 or CLE42 genes show delayed senescence (Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b). Exogenous application of synthetic 12-amino-acid CLE motifs can mimic the endogenous functions of CLE peptides (Zhang et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2022). Similarly, leaves treated with synthetic CLE14 or CLE42 peptides also display a delayed senescence phenotype (Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b). Notably, CLE14 and CLE42 peptides activate distinct signaling pathways to modulate leaf senescence (Figure 1A) (Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b). CLE14 peptide upregulates the expression of JUNGBRUNNEN1 (JUB1), a NAC family transcription factor, which in turn enhances the expression of reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging genes, thereby reducing ROS levels and delaying senescence (Zhang et al., 2022a). Conversely, CLE42 peptide downregulates the expression of ACC synthases (ACSs), key enzymes in ethylene biosynthesis, resulting in lower ethylene levels (Zhang et al., 2022b). The decreased ethylene level in leaves leads to the accumulation of EIN3-BINDING F-BOX (EBF) proteins, which mediate the degradation of ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 (EIN3) protein via the proteasome pathway (Guo and Ecker, 2003), thereby impairing EIN3 function and ethylene responses, ultimately delaying leaf senescence (Figure 1A). The LRR-RLK PHLOEM INTERCALATED WITH XYLEM (PXY) partially transmits CLE42 signal to regulate leaf senescence. Overall, CLE peptides modulate leaf senescence through distinct signaling mechanisms (Figure 1A) (Han et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b).

Figure 1. Small signaling peptides regulate leaf senescence. (A) In leaf cells, the leaf senescence associated small signaling peptides are synthesized in cytoplasm and undergo processing or post-translational modifications in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus. Subsequently, they are transported to the apoplast, where they execute their physiological functions. Unknown receptors detect the CLE14 signal, leading to the transcriptional activation of JUB1 expression. JUB1 subsequently enhances the transcription of ROS scavenging genes such as CAT3, APX1, and APX3, resulting in a reduction of ROS levels and a postponement of leaf senescence. CLE42 interacts with PXY and unidentified receptors to inhibit ACS2 expression, thereby decreasing ethylene levels. The reduced ethylene content induces the accumulation of EBF1 proteins, which disrupt the function of EIN3 and ethylene responses, ultimately delaying leaf senescence. PSKR1 recognizes the PSK peptide signal to delay leaf senescence via undefined mechanisms. SCOOP10 and SCOOP12 peptides antagonistically regulate leaf senescence in a MIK2-phosphorylation dependent manner. During the early stage of leaf senescence, the SCOOP10 peptide inhibits the biosynthesis of the SCOOP12 peptide. Subsequently, SCOOP10 directly binds to the receptor MIK2, inhibiting its phosphorylation and induces the SAGs expression, thereby promoting the senescence process. At the later stages, PROSCOOP12 is translated and processed into the SCOOP12 peptide. The SCOOP12 peptide then outcompetes the binding of SCOOP10 with MIK2, facilitating MIK2 phosphorylation and suppresses the SAGs expression, consequently delaying leaf senescence. The IDL6 peptide modulates leaf senescence via transcriptional regulation of WRKY TFs through unidentified receptors. Abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene also activate IDL6 signaling to influence leaf senescence. (B) Expression profiles of genes encoding LRR-RLKs and RAPID ALKALINIZATION FACTORs (RALFs), PLANT PEPTIDE CONTAINING SULFATED TYROSINE1 (PSY1), ROOT MERISTEM GROWTH FACTORs (RGFs), and ELICITOR PEPTIDE PRECURSORs (PROPEPs). Data is sourced from Lyu et al., 2019, and the heatmap is generated using TBtools (Chen et al., 2023b) with the average log FPKM values. P: phosphorylation. Dashed line means indirect regulations.

3 SCOOP peptides antagonistically regulate leaf senescence

SCOOPs are classified into the phytocytokine peptide family. The precursors of SCOOPs, known as PROSCOOPs, undergo proteolytic processing at the N-terminus to yield the bioactive C-terminal SCOOP peptides (Gully et al., 2019). In Arabidopsis thaliana genome, over 50 SCOOP peptide members have been identified (Yang et al., 2023), and they play pivotal roles in plant immune responses (Gully et al., 2019; Hou et al., 2021; Rhodes et al., 2021; Stahl et al., 2022; Jia et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2024), root development (Guillou et al., 2022a; Wang et al., 2024), flowering timing (Guillou et al., 2022b), and leaf senescence (Zhang et al., 2024a; Brusslan, 2025). PROSCOOP expression varies at different stages of leaf development, with PROSCOOP10 showing upregulated expression at early senescence stage, while PROSCOOP12 being markedly upregulated in later senescence stages, indicating their roles in leaf senescence process (Zhang et al., 2024a). Mutations in PROSCOOP10 results in delayed leaf senescence, while exogenous application of synthetic SCOOP10 peptide induces premature senescence (Zhang et al., 2024a). Furthermore, overexpression of PROSCOOP10 similarly promotes premature senescence. Conversely, application of synthetic SCOOP12 peptide or overexpression of PROSCOOP12 delays senescence, suggesting antagonistic functions of SCOOP10 and SCOOP12 peptides in leaf senescence regulation (Zhang et al., 2024a).

The LRR-RLK receptor, MALE DISCOVERER 1-INTERACTING RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE 2 (MIK2), has been identified as a receptor for SCOOP10 and SCOOP12 peptides (Hou et al., 2021; Rhodes et al., 2021). MIK2 is predominantly expressed in senescing leaves. The mik2 mutant exhibits accelerated senescence, while MIK2 overexpression transgenic lines show delayed senescence, indicating that MIK2 is crucial for leaf senescence (Zhang et al., 2024a). Microscale thermophoresis (MST) assays corroborate the competitive binding of SCOOP10 and SCOOP12 peptides to MIK2 receptor. Further investigations reveal that SCOOP10 peptide inhibits MIK2 phosphorylation, whereas SCOOP12 peptide enhances MIK2 phosphorylation. Additionally, SCOOP12 peptide suppresses the expression of SAGs-induced and MIK2 phosphorylation by SCOOP10 peptide. Collectively, SCOOP12 peptide antagonizes SCOOP10 peptide by modulating MIK2 phosphorylation and senescence signaling pathways during late senescence stages, thereby finely regulating the leaf senescence process (Figure 1A) (Zhang et al., 2024a).

4 PSK and IDA peptides participate in leaf senescence regulation

PSKs constitute a group of disulfated pentapeptides, encompassing four bioactive variants: PSK-α, -γ, -δ, and -ϵ. These peptides are perceived by plasma membrane-localized receptors, known as PSK RECEPTORs (PSKRs), to modulate various physiological processes including cellular proliferation and expansion, plant reproduction, somatic embryogenesis, regeneration, legume nodulation, leaf senescence, and stress resilience against biotic and abiotic clues (Yamakawa et al., 1999; Matsubayashi et al., 2006; Li et al., 2024). Exogenous application of the PSK-α peptide has been observed to delay leaf senescence, potentially by regulating chlorophyll integrity (Figure 1A) (Yamakawa et al., 1999). Mutation of PSKR receptor accelerates the senescence process (Matsubayashi et al., 2006). Nonetheless, conflicting evidence exists concerning the involvement of PSKR1 receptors in leaf senescence (Matsubayashi et al., 2006; Yadav et al., 2024). Crucially, the bioactivation of PSK peptides necessitates tyrosine sulfation, catalyzed by the transmembrane enzyme tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase (TPST). Consequently, a loss-of-function mutation in TPST precipitates premature leaf senescence, mirroring the effects observed with PSK peptide application (Yamakawa et al., 1999; Matsubayashi et al., 2006; Komori et al., 2009).

The IDA/IDL peptides, initially identified for their critical role in organ abscission, are also implicated in various biological processes, including responses to biotic and abiotic stress (Wang et al., 2023). IDL6 transcription is markedly upregulated in leaves during both early and late senescence stages, indicating its involvement in leaf senescence (Guo et al., 2022). The idl6 loss-of-function mutant exhibits a pronounced delay in leaf senescence, and this delayed senescence phenotype can be reversed by reintroducing the IDL6 gene into idl6 mutant plants. In contrast, leaves overexpressing IDL6 or treated with exogenous synthetic IDL6 peptide display an early senescence phenotype. Transcriptomic analysis reveals that WRKY53, WRKY38, and WRKY62 TFs may act downstream of IDL6 in promoting leaf senescence. Additionally, IDL6 may also play a role in abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene-mediated acceleration of leaf senescence (Figure 1A) (Guo et al., 2022).

5 Future perspectives

Leaf senescence represents an essential evolutionary strategy that enhances plant fitness and survival by facilitating nutrient remobilization to support the growth of sink organs, such as roots, stems, and flowers (Woo et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2021; Ahmad et al., 2024). While these studies have elucidated the intricate roles of small signaling peptides in leaf senescence (Figure 1A), several unresolved questions remain to be explored in future researches. The answers to these questions will accelerate the application of small signaling peptides in agriculture to recycle of the nutrients.

1. Characterization of novel small signaling peptides in leaf senescence. The expression level of several small signaling peptide genes, such as RAPID ALKALINIZATION FACTORs (RALFs), PLANT PEPTIDE CONTAINING SULFATED TYROSINE1 (PSY1), ROOT MERISTEM GROWTH FACTORs (RGFs), and ELICITOR PEPTIDE PRECURSORs (PROPEPs) are also regulated during senescence (Figure 1B) (Lyu et al., 2019), indicating the presence of unidentified small signaling peptides involved in the regulation of leaf senescence. Mass spectrometry (MS) is a reliable method to identify and verify most peptide members in plants. However, MS has limitations in detecting low-abundance peptides in plants. Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) techniques offer advanced capabilities with superior sensitivity and high spatial resolution, enabling the visualization of the spatial distribution of small peptides at various stages of leaf senescence, even at single-cell resolution (García-Rojas et al., 2024; Petřík et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024b). Integrating MSI with MS techniques will facilitate the identification of previously uncharacterized small signaling peptides involved in leaf senescence.

2. How to maintain the homeostasis of small signaling peptides during leaf senescence? Plants synthesize a multitude of small signaling peptides (Xie et al., 2022; Ji et al., 2025; Xiao et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025) as well as noncanonical peptides (NCPs) (Wang et al., 2020; Pei et al., 2022; Sami et al., 2024). These peptides appear to play synergistic or antagonistic roles in leaf senescence (Figure 1A), although their interactions in leaf senescence are not clear. Therefore, it is crucial to understand how plants precisely regulate the levels of these small signaling peptides to achieve optimal cellular responses to senescence cues. Notably, the specific function of NCPs in the process of leaf senescence necessitates additional in-depth investigation in future. In addition, the application of PSK peptide has been shown to delay the senescence of fruits (Aghdam et al., 2021a) and cut flowers (Aghdam et al., 2021b), indicating a conserved regulatory function of PSK peptide in senescence mechanisms. Remarkably, numerous homologs of these senescence-associated small signaling peptides have been identified across various plant species (Ji et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). Nevertheless, their biological roles in the modulation of senescence processes in other plant species remain to be elucidated.

3. Identification of novel receptors. Typically, plasma membrane localized LRR-RLK receptors are capable of perceiving small signaling peptides, thereby modulating an array of signaling pathways (Furumizu and Aalen, 2023; Ji et al., 2025; Xiao et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). A couple of LRR-RLKs encoding genes, such as BARELY ANY MERISTEMs (BAMs) and CLAVATA1 (CLV1) are (de)activated in senescent leaves (Figure 1B), implying that these receptors might convey CLE, SCOOP, IDL6, or PSK signals to regulate leaf senescence. But their roles in leaf senescence requires further investigations. Moreover, 4-azidosalicylic acid-labeled peptides and CRISPR-based genetic screening systems present opportunities for the identification of novel receptors specific to leaf senescence-related small signaling peptides, with high specificity and throughput (Shinohara and Matsubayashi, 2017; Gaillochet et al., 2021). Additionally, various in vitro analytical techniques, employing either labeled or label-free ligands, can be utilized to validate interactions between small signaling peptides and their corresponding receptors (Sandoval and Santiago, 2020).

4. Construction of regulatory networks at the (post)transcriptional and (post)translational levels. As mentioned, the intricate signaling pathways involved in small signaling peptides-mediated leaf senescence regulation remain largely elusive (Figure 1A). Recently, a comprehensive single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) transcriptomic analysis has facilitated the identification of pivotal hub genes that governs leaf senescence (Guo et al., 2025). Spatial transcriptomic technologies enable the precise localization and quantification of spatial gene expression across various plant tissues and developmental stages (Yin et al., 2023; Sang and Kong, 2024). These advanced RNA-seq methodologies will uncover differentially expressed gene clusters that specifically respond to leaf senescence-related small signaling peptides. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) of proteins, including acetylation, crotonylation, glycosylation, lysine lactylation, methylation, phosphorylation, SUMOylation, and ubiquitylation, are ubiquitous in diverse biological processes, ensuring rapid and tight regulation of signal transduction and cellular responses during leaf senescence (Woo et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021; Guo et al., 2021). The advent of 4D proteomics (Chen et al., 2023a; Hao et al., 2023) allows for in-depth proteomic exploration with high speed, robustness, sensitivity, and selectivity. This technique will offer crucial insights into protein abundance, stability, and post-translational modifications in leaf senescence (Han et al., 2022). Furthermore, epigenetic regulation plays a vital role in leaf senescence (Ostrowska-Mazurek et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Miryeganeh, 2022; Jeong et al., 2025). CRISPR-based epigenetic tools, such as CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), CRISPR/dCas9 activation (CRISPRa), and CRISPR-dCas9-DNMT3A (Jogam et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Qi et al., 2023), can be employed to investigate the effects of small peptides on senescence-related gene expression and epigenetic regulations. In summary, leveraging advanced RNA-seq and proteomic technologies will facilitate the construction of unprecedented transcriptional and protein networks mediated by small signaling peptides that control leaf senescence.

5. How small signaling peptides integrate phytohormones and environmental cues. Leaf senescence can be triggered by various abiotic factors such as light, circadian rhythms, drought, salinity, nitrogen deprivation, and high temperatures (Woo et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2025; Vander Mijnsbrugge et al., 2025). The reported data primarily elucidated the biological functions of these small signaling peptides in the regulation of age-dependent leaf senescence. Importantly, the transcriptional levels of CLE14/CLE42, IDL6, PROSCOOP10/12 were induced in response to environmental stressors associated with senescence, such as drought, salinity, and darkness (Guo et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b; Zhang et al., 2024a). This suggests that senescence associated small signaling peptides may be involved in stress-induced leaf senescence, although further research is warranted to confirm their interactions. Moreover, phytohormones are pivotal in modulating leaf senescence via intricate interactions (Guo et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2022). Notably, small signaling peptides are implicated in the response to phytohormones (Morcillo et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2025; Ji et al., 2025; Mou et al., 2025). This may indicate that senescence associated small signaling peptides may also serve as crucial integrators to link with hormonal pathways to regulate leaf senescence. Nonetheless, the precise mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

Author contributions

LQ: Writing – original draft. RL: Writing – original draft. ZZ: Writing – original draft. JN: Writing – original draft. YW: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. JL: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. HH: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work is supported by funding from Jiangxi Agricultural University (9232308314), Science and Technology Department of Jiangxi Province (20223BCJ25037), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32460081) to Huibin Han; Science and Technology Department of Jiangxi Province (20232BAB205041) to Jianping Liu; Education Department of Jiangxi Province (GJJ2200441) to Yue Wang.

Acknowledgments

We thank other lab members for their critical comments on this manuscript. We also express our appreciations to the editor and reviewers for their insightful and constructive feedback, which has significantly improved our manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aghdam, M. S., Ebrahimi, A., and Sheikh-Assadi, M. (2021b). Phytosulfokine α (PSKα) delays senescence and reinforces SUMO1/SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 signaling pathway in cut rose flowers (Rosa hybrida cv. Angelina). Sci. Rep. 11, 23227. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02712-2

Aghdam, M. S., Flores, F. B., and Sedaghati, B. (2021a). Exogenous phytosulfokine-α (PSKα) application delays senescence and relieves decay in strawberry fruit during cold storage by triggering extracellular ATP signaling and improving ROS scavenging system activity. Sci. Hortic. 279, 109906. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2021.109906

Ahmad, Z., Ramakrishnan, M., Wang, C., Rehman, S., Shahzad, A., and Wei, Q. (2024). Unravelling the role of WRKY transcription factors in leaf senescence: Genetic and molecular insights. J. Adv. Res. S2090-1232(24)00428-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2024.09.026

Asim, M., Zhang, Y., Sun, Y., Guo, M., Khan, R., Wang, X. L., et al. (2023). Leaf senescence attributes: the novel and emerging role of sugars as signaling molecules and the overlap of sugars and hormones signaling nodes. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 43, 1092–1110. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2022.2094215

Bengoa Luoni, S., Astigueta, F. H., Nicosia, S., Moschen, S., Fernandez, P., and Heinz, R. (2019). Transcription factors associated with leaf senescence in crops. Plants 8, 411. doi: 10.3390/plants8100411

Brusslan, J. A. (2025). Getting the SCOOP on peptide ligands that regulate leaf senescence. Mol. Plant 18, 384–385. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2025.01.013

Cao, J., Liu, H., Tan, S., and Li, Z. (2023). Transcription factors-regulated leaf senescence: current knowledge, challenges and approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 9245. doi: 10.3390/ijms24119245

Chen, J., Wang, H., Wang, J., Zheng, X., Qu, W., Fang, H., et al. (2025). Fertilization-induced synergid cell death by RALF12-triggered ROS production and ethylene signaling. Nat. Commun. 16, 3059. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-58246-y

Chen, C., Wu, Y., Li, J., Wang, X., Zeng, Z., Xu, J., et al. (2023b). TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 16, 1733–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2023.09.010

Chen, M., Zhu, P., Wan, Q., Ruan, X., Wu, P., Hao, Y., et al. (2023a). High-coverage four-dimensional data-independent acquisition proteomics and phosphoproteomics enabled by deep learning-driven multidimensional predictions. Anal. Chem. 95, 7495–7502. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c05414

Fletcher, J. C. (2020). Recent advances in arabidopsis CLE peptide signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 25, 1005–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2020.04.014

Furumizu, C. and Aalen, R. B. (2023). Peptide signaling through leucine-rich repeat receptor kinases: insight into land plant evolution. New Phytol. 238, 977–982. doi: 10.1111/nph.v238.3

Gaillochet, C., Develtere, W., and Jacobs, T. B. (2021). CRISPR screens in plants: approaches, guidelines, and future prospects. Plant Cell. 33, 794–813. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab099

García-Rojas, N. S., Sierra-Álvarez, C. D., Ramos-Aboites, H. E., Moreno-Pedraza, A., and Winkler, R. (2024). Identification of plant compounds with mass spectrometry imaging (MSI). Metabolites 14, 419. doi: 10.3390/metabo14080419

Guillou, M. C., Balliau, T., Vergne, E., Canut, H., Chourré, J., Herrera-León, C., et al. (2022b). The PROSCOOP10 gene encodes two extracellular hydroxylated peptides and impacts flowering time in arabidopsis. Plants 11, 3554. doi: 10.3390/plants11243554

Guillou, M. C., Vergne, E., Aligon, S., Pelletier, S., Simonneau, F., Rolland, A., et al. (2022a). The peptide SCOOP12 acts on reactive oxygen species homeostasis to modulate cell division and elongation in Arabidopsis primary root. J. Exp. Bot. 73, 6115–6132. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erac240

Gully, K., Pelletier, S., Guillou, M. C., Ferrand, M., Aligon, S., Pokotylo, I., et al. (2019). The SCOOP12 peptide regulates defense response and root elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 1349–1365. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery454

Guo, H. and Ecker, J. R. (2003). Plant responses to ethylene gas are mediated by SCF (EBF1/EBF2)-dependent proteolysis of EIN3 transcription factor. Cell 115, 667–677. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00969-3

Guo, C., Li, X., Zhang, Z., Wang, Q., Zhang, Z., Wen, L., et al. (2022). The INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION-LIKE6 peptide functions as a positive modula tor of Leaf Senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 909378. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.909378

Guo, Y., Ren, G., Zhang, K., Li, Z., Miao, Y., and Guo, H. (2021). Leaf senescence: progression, regulation, and application. Mol. Hortic. 1, 5. doi: 10.1186/s43897-021-00006-9

Guo, X., Wang, Y., Zhao, C., Tan, C., Yan, W., Xiang, S., et al. (2025). An Arabidopsis single-nucleus atlas decodes leaf senescence and nutrient allocation. Cell. 188, 2856–2871.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.03.024

Han, H., Zhuang, K., and Qiu, Z. (2022). CLE peptides join the plant longevity club. Trends Plant Sci. 27, 961–963. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2022.07.001

Hao, Y., Chen, M., Huang, X., Xu, H., Wu, P., and Chen, S. (2023). 4D-diaXLMS: proteome-wide four-dimensional data-independent acquisition workflow for cross-linking mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 95, 14077–14085. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.3c02824

Hou, S., Liu, D., Huang, S., Luo, D., Liu, Z., Xiang, Q., et al. (2021). The Arabidopsis MIK2 receptor elicits immunity by sensing a conserved signature from phytocytokines and microbes. Nat. Commun. 12, 5494. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25580-w

Huang, P., Li, Z., and Guo, H. (2022). New advances in the regulation of leaf senescence by classical and peptide hormones. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 923136. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.923136

Jeong, U., Lim, P. O., and Woo, H. R. (2025). Emerging regulatory mechanisms of leaf senescence: Insights into epigenetic regulators, non-coding RNAs, and peptide hormones. J. Plant Biol. 68, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12374-025-09456-w

Ji, C., Li, H., Zhang, Z., Peng, S., Liu, J., Zhou, Y., et al. (2025). The power of small signaling peptides in crop and horticultural plants. Crop J. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2024.12.020

Jia, F., Xiao, Y., Feng, Y., Yan, J., Fan, M., Sun, Y., et al. (2024). N-glycosylation facilitates the activation of a plant cell-surface receptor. Nat. Plants 10, 2014–2026. doi: 10.1038/s41477-024-01841-6

Jibran, R., A Hunter, D., and Dijkwel, P. (2013). Hormonal regulation of leaf senescence through integration of developmental and stress signals. Plant Mol. Biol. 82, 547–561. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0043-2

Jogam, P., Sandhya, D., Alok, A., Peddaboina, V., Allini, V. R., and Zhang, B. (2022). A review on CRISPR/Cas-based epigenetic regulation in plants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 219, 1261–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.08.182

Kang, J., Wang, X., Ishida, T., Grienenberger, E., Zheng, Q., Wang, J., et al. (2022). A group of CLE peptides regulates de novo shoot regeneration in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 235, 2300–2312. doi: 10.1111/nph.v235.6

Komori, R., Amano, Y., Ogawa-Ohnishi, M., and Matsubayashi, Y. (2009). Identification of tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106, 15067–15072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902801106

Li, Y., Di, Q., Luo, L., and Yu, L. (2024). Phytosulfokine peptides, their receptors, and functions. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1326964. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1326964

Liu, G., Lin, Q., Jin, S., and Gao, C. (2022). The CRISPR-Cas toolbox and gene editing technologies. Mol. Cell. 82, 333–347. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.12.002

Lyu, J. I., Kim, J. H., Chu, H., Taylor, M. A., Jung, S., Baek, S. H., et al. (2019). Natural allelic variation of GVS1 confers diversity in the regulation of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 221, 2320–2334. doi: 10.1111/nph.2019.221.issue-4

Matsubayashi, Y., Ogawa, M., Kihara, H., Niwa, M., and Sakagami, Y. (2006). Disruption and overexpression of Arabidopsis phytosulfokine receptor gene affects cellular longevity and potential for growth. Plant Physiol. 142, 45–53. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.081109

Miryeganeh, M. (2022). Epigenetic mechanisms of senescence in plants. Cells 11, 251. doi: 10.3390/cells11020251

Morcillo, R. J. L., Leal-López, J., Férez-Gómez, A., López-Serrano, L., Baroja-Fernández, E., Gámez-Arcas, S., et al. (2024). RAPID ALKALINIZATION FACTOR 22 is a key modulator of the root hair growth responses to fungal ethylene emissions in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 196, 2890–2904. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiae484

Mou, W., Khare, R., Polko, J. K., Taylor, I., Xu, J., Xue, D., et al. (2025). Ethylene-independent modulation of root development by ACC via downregulation of WOX5 and group I CLE peptide expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 122, e2417735122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2417735122

Olsson, V., Joos, L., Zhu, S., Gevaert, K., Butenko, M. A., and De Smet, I. (2019). Look closely, the beautiful may be small: Precursor-derived peptides in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 70, 153–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040413

Ostrowska-Mazurek, A., Kasprzak, P., Kubala, S., Zaborowska, M., and Sobieszczuk-Nowicka, E. (2020). Epigenetic landmarks of leaf senescence and crop improvement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 5125. doi: 10.3390/ijms21145125

Pei, M. S., Liu, H. N., Wei, T. L., Yu, Y. H., and Guo, D. L. (2022). Large-scale discovery of non-conventional peptides in grape (Vitis vinifera L.) through peptidogenomics. Hortic. Res. 9, uhac023. doi: 10.1093/hr/uhac023

Petřík, I., Hladík, P., Zhang, C., Pěnčík, A., and Novák, O. (2024). Spatio-temporal plant hormonomics: from tissue to subcellular resolution. J. Exp. Bot. 75, 5295–5311. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erae267

Qi, Q., Hu, B., Jiang, W., Wang, Y., Yan, J., Ma, F., et al. (2023). Advances in plant epigenome editing research and its application in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 3442. doi: 10.3390/ijms24043442

Rhodes, J., Yang, H., Moussu, S., Boutrot, F., Santiago, J., and Zipfel, C. (2021). Perception of a divergent family of phytocytokines by the Arabidopsis receptor kinase MIK2. Nat. Commun. 12, 705. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-20932-y

Sami, A., Fu, M., Yin, H., Ali, U., Tian, L., Wang, S., et al. (2024). NCPbook: A comprehensive database of noncanonical peptides. Plant Physiol. 196, 67–76. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiae311

Sandoval, P. J. and Santiago, J. (2020). In vitro analytical approaches to study plant ligand-receptor interactions. Plant Physiol. 182, 1697–1712. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.01396

Sang, Q. and Kong, F. (2024). Applications for single-cell and spatial transcriptomics in plant research. New Crops 1, 100025. doi: 10.1016/j.ncrops.2024.100025

Shinohara, H. and Matsubayashi, Y. (2017). Photoaffinity labeling of plant receptor kinases. Methods Mol. Biol. 1621, 59–68. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7063-6_6

Stahl, E., Fernandez Martin, A., Glauser, G., Guillou, M. C., Aubourg, S., Renou, J. P., et al. (2022). The MIK2/SCOOP signaling system contributes to Arabidopsis resistance against herbivory by modulating jasmonate and indole glucosinolate biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 852808. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.852808

Tan, S., Sha, Y., Sun, L., and Li, Z. (2023). Abiotic stress-induced leaf senescence: Regulatory mechanisms and application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 11996. doi: 10.3390/ijms241511996

Vander Mijnsbrugge, K., Moreels, S., Moreels, S., Buisset, D., Vancampenhout, K., and Notivol Paino, E. (2025). Influence of summer drought on post-drought resprouting and leaf senescence in Prunus spinosa L. growing in a common garden. Plants 14, 1132. doi: 10.3390/plants14071132

Wang, X., Chen, M., Li, J., Kong, M., and Tan, S. (2024). The SCOOP-MIK2 immune pathway modulates Arabidopsis root growth and development by regulating PIN-FORMED abundance and auxin transport. Plant J. 120, 318–334. doi: 10.1111/tpj.v120.1

Wang, Z., Guo, J., Luo, W., Niu, S., Qu, L., Li, J., et al. (2025). Salicylic Acid cooperates with lignin and sucrose signals to alleviate waxy maize leaf senescence under heat stress. Plant Cell Environ. 48, 4341–4355 doi: 10.1111/pce.15437

Wang, S., Tian, L., Liu, H., Li, X., Zhang, J., Chen, X., et al. (2020). Large-scale discovery of non-conventional peptides in maize and Arabidopsis through an integrated peptidogenomic pipeline. Mol. Plant 13, 1078–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.05.012

Wang, P., Wu, T., Jiang, C., Huang, B., and Li, Z. (2023). Brt9SIDA/IDALs as peptide signals mediate diverse biological pathways in plants. Plant Sci. 330, 111642. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2023.111642

Woo, H. R., Kim, H. J., Lim, P. O., and Nam, H. G. (2019). Leaf senescence: systems and dynamics aspects. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 70, 347–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-095859

Wu, H., Wan, L., Liu, Z., Jian, Y., Zhang, C., Mao, X., et al. (2024). Mechanistic study of SCOOPs recognition by MIK2-BAK1 complex reveals the role of N-glycans in plant ligand-receptor-coreceptor complex formation. Nat. Plants 10, 1984–1998. doi: 10.1038/s41477-024-01836-3

Xiao, F., Zhou, H., and Lin, H. (2025). Decoding small peptides: Regulators of plant growth and stress resilience. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 67, 596–631. doi: 10.1111/jipb.13873

Xie, H., Zhao, W., Li, W., Zhang, Y., Hajný, J., and Han, H. (2022). Small signaling peptides mediate plant adaptions to abiotic environmental stress. Planta 255, 72. doi: 10.1007/s00425-022-03859-6

Yadav, N., Nagar, P., Rawat, A., and Mustafiz, A. (2024). Phytosulfokine receptor 1 (AtPSKR1) acts as a positive regulator of leaf senescence by mediating ROS signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Env Exp. Bot. 220, 105674. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2024.105674

Yamakawa, S., Matsubayashi, Y., Sakagami, Y., Kamada, H., and Satoh, S. (1999). Promotive effects of the peptidyl plant growth factor, phytosulfokine-alpha, on the growth and chlorophyll content of Arabidopsis seedlings under high night-time temperature conditions. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63, 2240–2243. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.2240

Yang, H., Kim, X., Skłenar, J., Aubourg, S., Sancho-Andrés, G., Stahl, E., et al. (2023). Subtilase-mediated biogenesis of the expanded family of SERINE RICH ENDOGENOUS PEPTIDES. Nat. Plants 9, 2085–2094. doi: 10.1038/s41477-023-01583-x

Yin, R., Xia, K., and Xu, X. (2023). Spatial transcriptomics drives a new era in plant research. Plant J. 116, 1571–1581. doi: 10.1111/tpj.v116.6

Zhang, Z., Gigli-Bisceglia, N., Li, W., Li, S., Wang, J., Liu, J., et al. (2024a). SCOOP10 and SCOOP12 peptides act through MIK2 receptor-like kinase to antagonistically regulate Arabidopsis leaf senescence. Mol. Plant 17, 1805–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2024.10.010

Zhang, Y. M., Guo, P., Xia, X., Guo, H., and Li, Z. (2021). Multiple layers of regulation on leaf senescence: new advances and perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 788996. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.788996

Zhang, Z., Han, H., Zhao, J., Liu, Z., Deng, L., Wu, L., et al. (2025). Peptide hormones in plants. Mol. Hortic. 5, 7. doi: 10.1186/s43897-024-00134-y

Zhang, Z., Liu, C., Li, K., Li, X., Xu, M., and Guo, Y. (2022a). CLE14 functions as a “brake signal” to suppress age-dependent and stress-induced leaf senescence by promoting JUB1-mediated ROS scavenging in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 15, 179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.09.006

Zhang, H., Lu, K. H., Ebbini, M., Huang, P., Lu, H., and Li, L. (2024b). Mass spectrometry imaging for spatially resolved multi-omics molecular mapping. NPJ Imaging 2, 20. doi: 10.1038/s44303-024-00025-3

Zhang, L., Shi, X., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Yang, J., Ishida, T., et al. (2019). CLE9 peptide-induced stomatal closure is mediated by abscisic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and nitric oxide in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 42, 1033–1044. doi: 10.1111/pce.13475

Keywords: leaf senescence, CLE peptide, SCOOP peptide, MIK2, ROS

Citation: Qiu L, Lu R, Zhang Z, Nie J, Wang Y, Liu J and Han H (2025) Small signaling peptides define leaf longevity. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1616650. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1616650

Received: 23 April 2025; Accepted: 06 June 2025;

Published: 20 June 2025.

Edited by:

Giampiero Cai, University of Siena, ItalyReviewed by:

Kun Li, Henan University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Qiu, Lu, Zhang, Nie, Wang, Liu and Han. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jianping Liu, amlhbnBpbmdsaXVAanhhdS5lZHUuY24=; Huibin Han, aHVpYmluaGFuQGp4YXUuZWR1LmNu

Liping Qiu1

Liping Qiu1 Jianping Liu

Jianping Liu Huibin Han

Huibin Han