Abstract

Challenging environmental conditions are major factors that severely affect plant growth and limit agricultural productivity. To mitigate these stresses, plants have evolved various adaptive mechanisms. Among these, Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) proteins play a pivotal role in responding to abiotic stresses and participate in a reciprocal regulatory network with the abscisic acid (ABA) signaling pathway. However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying this reciprocity and the full composition of this network require systematic integration. This review synthesizes recent advances to propose a novel “ABA-LEA feedback loop” model and presents a comprehensive analysis of the classification into seven groups, structural features, molecular functions and mechanisms by which LEA proteins contribute to plant stress resistance. Special emphasis is placed on the intricate interplay between LEA proteins and the ABA signaling pathway, encompassing both the ABA-dependent regulation of LEA expression and the reciprocal feedback exerted by LEA proteins on ABA signaling through mechanisms that influence ABA homeostasis and signaling. By synthesizing evidence for this reciprocal regulation, this review establishes a novel feedback loop model that redefines LEA proteins as active modulators rather than passive effectors in stress signaling, offering new theoretical targets for breeding stress-resilient crops.

1 Introduction

Abiotic stresses, such as drought, heat, cold and excess salt, result in significant challenges to plant growth and productivity. In response, plants activate complex adaptive mechanisms that include hormonal signaling, transcriptional reprogramming, and the activation of protective proteins (Waadt et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). Among these responses, LEA proteins play a pivotal role as molecular protectors. Initially identified for their seed-specific accumulation during cotton embryogenesis (Dure et al., 1981; Bojórquez-Velázquez et al., 2019), LEA proteins are now recognized as key stress resistance factors, ubiquitously expressed across plant organs (roots, stems, leaves) and in phylogenetically diverse organisms (Battaglia et al., 2008; Du et al., 2013; Charfeddine et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2019a; Knox-Brown et al., 2020; Kosová et al., 2021; Hsiao, 2024). Their distinct biophysical properties (exceptional thermostability, high hydrophilicity, and resistance to denaturation) facilitate the stabilization of cellular structures under extreme environmental conditions (Guo et al., 2023).

LEA expression is primarily regulated by ABA, a central signaling molecule that coordinates stress-response networks (Leprince et al., 2017; Müller et al., 2017). Emerging evidence indicates a reciprocal relationship between LEA proteins and ABA pathways, where LEA proteins both respond to and actively modulate ABA signaling, suggesting bidirectional crosstalk within a more extensive stress-adaptation network. Despite comprehensive genomic characterization of LEA families across diverse taxa (Battaglia et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2019a; Knox-Brown et al., 2020; Kosová et al., 2021), significant knowledge gaps remain regarding their underlying functional mechanisms: the evolutionary divergence of LEA structural and functional traits across different plant lineages remains insufficiently explored; mechanistic insights into LEA-mediated stress protection remain fragmented across various studies; and the regulation between LEA proteins and ABA signaling has yet to be systematically integrated.

In this review, we synthesize existing research by systematizing the classification and structural principles of LEA proteins, elucidating their mechanistic roles in abiotic stress mitigation, and proposing a unified model for dynamic LEA-ABA signaling interactions. This analysis aims to guide future engineering of stress-resistant crops through targeted manipulation of LEA-based regulatory networks.

2 Structural characteristics and classification of LEA proteins

LEA proteins, which are recognized for their critical roles in plant stress tolerance, constitute a family of hydrophilic polypeptides (Szlachtowska and Rurek, 2023). These proteins typically possess conserved sequence motifs, characterized by repeated arrangements of hydrophilic residues, including glycine (Gly), alanine (Ala), and glutamate (Glu) (Hundertmark and Hincha, 2008; Du et al., 2013). Despite this sequence conservation, LEA proteins exhibit structural plasticity. Computational and experimental studies reveal that they generally lack stable secondary structures in solution, classifying them as intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) (Hincha and Thalhammer, 2012; Wang et al., 2024b). Remarkably, their conformation is stress-responsive: under hydration they remain disordered, whereas under dehydration they reversibly fold into ordered α-helices (Hundertmark et al., 2011; Rendón-Luna et al., 2024). This structural transition is fully reversible upon rehydration (Hincha and Thalhammer, 2012).

This interplay between sequence motifs and structural dynamics directly informs classification systems. The classification of LEA proteins is complex due to divergent criteria, primarily based on sequence motifs or polar amino acid composition (Zheng et al., 2019). The widely adopted Battaglia framework categorizes LEA proteins into seven groups based on distinct domain architectures and characteristic motifs (Battaglia et al., 2008), the key features of which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Group | Common name | Key defining features/characteristic motifs | Structural notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | 20-aa motif: TRKEQ[L/M]G[T/E]EGY[Q/K]EMGRKGG[L/E] | – |

| 2 | Dehydrins (DHNs) | Lysine-rich 15-aa K-segment: EKKGIMDKIKEKLPG | Predicted to form α-helical structures |

| 3 | – | 11-mer hydrophobic motif: FF[E/Q]XFK[E/Q]KFX[E/D/Q]1 | – |

| 4 | – | N-terminal α-helix-forming domain; disordered C-terminal region | – |

| 5 | – | Lacks distinctive conserved motifs | – |

| 6 | – | Conserved domain 1: LEDYKMQGYGTQGHQQPKPGRG Conserved domain 2: GSTDAPTLSGGAV |

Low molecular weight |

| 7 | ASR proteins | ABA-water deficit stress (ABA/WDS) domain | Absent in Arabidopsis thaliana |

Classification and characteristic features of LEA protein groups based on the Battaglia framework.

¹X denotes any amino acid; F represents hydrophobic residues.

Although useful, the Battaglia framework faces challenges when applied across diverse plant species. Extensive studies have revealed systematic discrepancies between its theoretical groups and empirically defined subfamilies. For example, 51 Arabidopsis thaliana LEA genes were classified into nine subfamilies, with two unclassified proteins assigned to the AtM subgroup (Hundertmark and Hincha, 2008). Additionally, 29 Solanum tuberosum LEA genes were categorized into nine subfamilies (Charfeddine et al., 2015), and 61 Salvia miltiorrhiza LEA genes were classified into seven subfamilies (Chen et al., 2021). For a comprehensive comparison across species, please refer to Table 2. To address species-specific variations while maintaining a domain-based classification, specialized resources such as the LEAPdb database (Hunault and Jaspard, 2010) have been developed. LEAPdb aids in the organization of hydrophilin data, classification of LEA proteins, functional experimentation, and structure-function analysis (Hunault and Jaspard, 2010).

Table 2

| Species | Members of the LEA proteins | Number of subfamily (group) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 51 | 9 | (Hundertmark and Hincha, 2008) |

| Solanum tuberosum | 29 | 9 | (Charfeddine et al., 2015) |

| Salvia miltiorrhiza | 61 | 7 | (Chen et al., 2021) |

| Oryza sativa | 34 | 7 | (Wang et al., 2007) |

| Citrillus lanatus | 73 | 4 | (Celik Altunoglu et al., 2017) |

| Cucumis melo | 61 | 3 | (Celik Altunoglu et al., 2017) |

| Camellia sinensis | 33 | 7 | (Wang et al., 2019a) |

| Triticum aestivum | 281 | 8 | (Zan et al., 2020) |

| Secale cereale | 112 | 8 | (Ding et al., 2021) |

| Phyllostachys edulis | 23 | 6 | (Huang et al., 2016) |

| Sorghum bicolor | 68 | 8 | (Nagaraju et al., 2019) |

| Citrus sinensis | 72 | 7 | (Pedrosa et al., 2015) |

| Solanum lycopersicum | 60 | 8 | (Jia et al., 2022) |

| Brassica napus | 306 | 8 | (Wang et al., 2024a) |

| Dendrobium officinale | 17 | 7 | (Ling et al., 2016) |

| Cucumis sativus | 79 | 7 | (Celik Altunoglu et al., 2016) |

|

P. armeniaca L. × P. sibirica L.

Malus domestica |

54 87 |

8 7 |

(Li et al., 2024) (Wang et al., 2024b) |

LEA proteins in different plants.

In conclusion, the defining features of LEA proteins include hydrophilicity, intrinsic disorder, and stress-responsive conformational shifts, such as dehydration-induced α-helix folding. These characteristics form the molecular basis of their role in plant stress adaptation. Moreover, evolved classification systems, which integrate domain-based frameworks with cross-species databases like LEAPdb, facilitate the systematic decoding of structure-function relationships. This integration accelerates research on stress resistance mechanisms.

3 Spatiotemporal expression and functions of LEA proteins under stress conditions

Structurally conserved motifs, which define LEA protein classification, govern their subcellular localization, enabling compartmentalized functions. Studies indicate that LEA proteins are distributed across various subcellular compartments (Candat et al., 2014; Ginsawaeng et al., 2021). This compartmentalized distribution of LEA proteins enables their direct involvement in protecting critical cellular components within specific organelles (Candat et al., 2014). They respond to stress signals, including those initiated by the key stress hormone ABA (Figure 1). Thirty-six Arabidopsis LEA proteins localize to the cytoplasm, and the majority are capable of nucleocytoplasmic trafficking into the nucleus (Candat et al., 2014). This dual positioning places them at the critical interface between cytoplasmic ABA signaling and ABA-triggered nuclear transcriptional reprogramming, suggesting potential direct regulation by ABA or their roles as downstream effectors. Phosphorylation plays a dynamic role in regulating LEA protein localization, as exemplified by maize Rab17. The wild-type protein localizes to the cytoplasm and nucleus, while the non-phosphorylatable mutant (mRab17) accumulates in the nucleolus (Riera et al., 2004). Since SNF1-related protein kinase 2 (SnRK2) are central to ABA signaling, ABA likely affects LEA protein localization and function through SnRK2-mediated phosphorylation.

Figure 1

Spatiotemporal expression, regulation, and compartmentalized functions of LEA proteins under abiotic stress. Abiotic stress triggers the accumulation of ABA, which activates SnRK2 kinases, leading to the phosphorylation of ABF transcription factors. These activated ABFs bind to ABRE motifs, thereby enhancing the expression of LEA proteins. LEA proteins are directed to specific subcellular compartments through structurally conserved targeting motifs, facilitating organelle-specific protection. Furthermore, the phosphorylation status of LEA proteins plays a critical role in their localization. For instance, in the case of ZmRab17, the wild-type protein localizes to both the cytoplasm and nucleus, while a phospho-deficient mutant (mRab17) accumulates in the nucleolus, illustrating the dynamic regulation of LEA protein subcellular distribution. Arrows denote positive regulation, where solid lines depict well-defined pathways and dashed lines represent speculative relationships. This figure was created using BioGDP.

LEA proteins are localized to specific subcellular regions, forming protective zones. Their ABA-regulated expression ensures precise timing, which enables rapid defense mobilization at stress sites. Genome-wide profiling of Arabidopsis LEA genes reveals two key patterns related to ABA-driven transcriptional control: first, organ-specific expression, with the highest levels in seeds, reflecting ABA’s role in dormancy; second, ABA/drought inducibility, as the promoters of most LEA genes contain ABRE motifs, which trigger rapid upregulation (Zheng et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2024). A strong correlation has also been observed between LEA protein accumulation and plant water deficit, further emphasizing their functional importance under water-limited conditions (Olvera-Carrillo et al., 2010; Guo et al., 2023). The expression patterns and structural features of LEA proteins suggest that they protect plant cells during dehydration and other stress conditions (Hunault and Jaspard, 2010; Olvera-Carrillo et al., 2010). This ABA-mediated spatiotemporal regulation supports LEA proteins as key molecular effectors in stress resilience.

Exploring the functions of these proteins helps deepen our understanding of plant adaptation to stress. Arabidopsis thaliana is a key model for studying the functions of LEA proteins, as shown in Table 3 (Kovacs et al., 2008; Thalhammer et al., 2010). Studies have shown that LEA13 and LEA30 enhance water stress tolerance by modulating stomatal density (López-Cordova et al., 2021). LEA4-2/LEA18 plays a key role in membrane stability (Hundertmark et al., 2011). COLD-REGULATED 15A (COR15A) and COR15B stabilize chloroplast membranes under freezing stress, protecting cells from cold-induced damage (Thalhammer et al., 2010; Navarro-Retamal et al., 2018; Hernández-Sánchez et al., 2024). RESPONSIVE TO ABSCISIC ACID 28 (RAB28) is crucial for ion homeostasis during late embryogenesis and germination, highlighting its role in early development (Borrell et al., 2002). LOW-TEMPERATURE-INDUCED 30 (LTI30) protects cellular membranes from dehydration-induced damage (Gupta et al., 2019), while SENESCENCE-ASSOCIATED GENE 21 (SAG21) enhances stress tolerance by modulating mitochondrial and chloroplast translation, underscoring its role in resilience (Karpinska et al., 2022).

Table 3

| Species | Names | Function | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | LEA13, LEA30 | Enhance water stress tolerance | Modulate stomatal density | (López-Cordova et al., 2021) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | LEA4-2/LEA18 | Modulate membrane stability | Anionic membrane-induced β-sheet folding and destabilization | (Hundertmark et al., 2011) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | COR15A, COR15B | Freezing protection | Chloroplast membrane stabilization | (Thalhammer et al., 2010; Navarro-Retamal et al., 2018; Hernández-Sánchez et al., 2024) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | RAB28 | Maintain ion homeostasis | Regulate cation balance | (Borrell et al., 2002) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | LTI30 | Prevent dehydration damage | Membrane protection | (Gupta et al., 2019) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | SAG21 | Enhance growth stress tolerance | Modulate organellar translation | (Karpinska et al., 2022) |

| Oryza sativa | OsLEA3-2 | Enhance drought tolerance | – | (Duan and Cai, 2012) |

| Triticum aestivum | WZY3-1 | Enhance drought tolerance | – | (Yu et al., 2019) |

| Phellodendron amurense | TaLEA3 | Improve drought resistance | Regulate stomatal closure | (Yang et al., 2018) |

| Capsicum annuum | CaDIL1 | Reduce drought tolerance | Impair ABA sensitivity | (Lim et al., 2018) |

| Glycine max | GmLEA4_19 | Increase drought tolerance | – | (Guo et al., 2023) |

| Zea mays | ZmDHN15 | Enhance cold tolerance | Reduce oxidative damage and electrolyte leakage | (Chen et al., 2022) |

| Oryza sativa | OsLEA1a | Protect membranes | Strengthen antioxidant defenses | (Wang et al., 2021) |

| Zea mays | ZmDHN1 | Stabilize cellular components | Phospholipid binding with α-helical increase | (Koag et al., 2009) |

| Ammopiptanthus mongolicus | AmDHN4 | Enhance multi-stress tolerance | – | (Liu et al., 2024) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AtLEA3-3 | Improve salt/osmotic tolerance | – | (Zhao et al., 2011) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | LEA4-5 | Reduce osmotic tolerance | Negatively regulated by BPC2 | (Li et al., 2021) |

Functions of LEA proteins.

These detailed mechanistic insights into the function of LEA proteins in Arabidopsis provide a crucial foundation for understanding their broader significance. Building on this knowledge, research has increasingly focused on exploring the potential of manipulating LEA gene expression to enhance stress tolerance, particularly drought resistance, in various plant species. Transgenic overexpression of OsLEA3–2 in Oryza sativa and the heterologous expression of wheat WZY3–1 in Arabidopsis thaliana enhance drought tolerance (Duan and Cai, 2012; Yu et al., 2019). Functional characterization shows that TaLEA3 enhances drought resistance in Phellodendron amurense by promoting faster stomatal closure (Yang et al., 2018). In contrast, reduced expression of Capsicum annuum Drought INDUCED LATE EMBRYOGENESIS ABUNDANT PROTEIN 1 (CaDIL1) in pepper weakens drought tolerance and ABA sensitivity (Lim et al., 2018). Guo et al. found that GmLEA4_19 overexpression enhances drought tolerance in both Arabidopsis and soybean (Guo et al., 2023).

A wealth of functional evidence underscores the critical contribution of LEA proteins to plant survival under low-temperature stress. For instance, overexpression of ZmDHN15 in Arabidopsis enhances low-temperature tolerance (Chen et al., 2022). This is demonstrated by reduced malondialdehyde content, lower relative electrolyte leakage, decreased reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, and improved seed germination and seedling survival rates compared to wild-type plants. Additionally, the stress-responsive gene OsLEA1a protects cellular membranes and strengthens antioxidant defenses under stress conditions (Wang et al., 2021). Maize DHN1 interacts with anionic phospholipid vesicles. This interaction is associated with an increase in the protein’s α-helical content (Koag et al., 2009). This conformational change is believed to contribute to membrane stabilization and the protection of other cellular components during stress. Similarly, AmDHN4 overexpression enhances tolerance to low temperature, drought, and osmotic stress in Arabidopsis (Liu et al., 2024).

In addition to their direct protective roles, some LEA proteins also modulate stress signaling pathways. For instance, overexpressing AtLEA3–3 in Arabidopsis enhances tolerance to salt and osmotic stress, while also increasing sensitivity to ABA (Zhao et al., 2011). Moreover, the regulation of LEA gene expression itself plays a key role in stress tolerance. Specifically, the transcription factor BASIC PENTACYSTEINE2 (BPC2) reduces osmotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis by repressing the expression of LEA4-5 (Li et al., 2021). This example highlights the complexity of the regulatory networks controlling LEA-mediated stress responses.

In summary, LEA proteins serve diverse functions in plant stress responses. Experimental evidence demonstrates that overexpressing LEA proteins enhances tolerance to drought, freezing, salt, and osmotic stress in transgenic plants, further highlighting their essential role in plant stress resistance (Hu and Xiong, 2014). LEA proteins are known to protect plants from abiotic stresses through multiple mechanisms, including acting as molecular chaperones, stabilizing membranes, and regulating ion homeostasis (Szlachtowska and Rurek, 2023; Hsiao, 2024). However, accumulating evidence indicates that LEA proteins also function as regulatory components within ABA signaling pathways, playing a critical role in mediating abiotic stress responses. Their functional importance is closely tied to their involvement in ABA signaling, which coordinates adaptive responses to environmental challenges. In the following section, we will examine the regulatory relationship between LEA proteins and ABA in detail.

4 Regulatory relationship between LEA proteins and ABA signaling

4.1 Regulation of LEA expression by ABA

The transcription of LEA genes is significantly induced by ABA (Table 4). As a key component of the ABA signaling pathway, the promoter regions of most LEA genes contain abscisic acid response elements (ABREs), which are recognized by ABRE binding factors/ABRE-binding proteins (ABFs/AREBs) (Liu et al., 2019b; Huang et al., 2022). For example, the transcription factor ABA INSENSITIVE 5 (ABI5) binds to ABREs in the promoters of LATE EMBRYOGENESIS ABUNDANT1 (EM1/LEA1) and EM6/LEA6 during seed germination. The application of exogenous ABA enhances the binding affinity of ABI5 to the EM6 promoter (Carles et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2012). Furthermore, the rice dehydrin OsDhn-Rab16D, whose promoter contains multiple ABREs, is inducible by ABA. OsDhn-Rab16D interacts with rice FK506 BINDING PROTEIN (OsFKBP), a prolyl cis-trans isomerase. This interaction, mediated by the ABA signaling pathway, enhances drought tolerance in rice (Tiwari et al., 2019). A model summarizing the ABA-mediated regulation of LEA proteins and their functional roles is presented in Figure 2.

Table 4

| Species | Names | Function | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | EM1 | Seed germination | ABA signaling | (Carles et al., 2002) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | EM6 | Seed germination | ABA signaling | (Carles et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2012) |

| Oryza sativa | RAB16D | Drought tolerance | ABA signaling | (Tiwari et al., 2019) |

| Oryza sativa | RAB21 | Water stress | ABA signaling | (Mundy and Chua, 1988) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | LEA5 | Oxidative stress tolerance | ABA synthesis | (Mowla et al., 2006) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | RAB18 | Freezing tolerance | ABA-Dependent | (Lång and Palva, 1992; Mantyla et al., 1995; Nylander et al., 2001) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | ABR | Leaf senescence | ABA signaling | (Su et al., 2016) |

| Triticum aestivum | SMP1 | Seed dormancy and germination | ABA signaling | (Xu et al., 2025) |

| Oryza sativa | RePRPs | Root growth | ABA signaling | (Tseng et al., 2013; Hsiao et al., 2020) |

| Medicago Sativa | LEA-D34 | Abiotic stress responses and flowering time | ABA signaling | (Lv et al., 2021) |

| Medicago falcata | LEA3 | Cold and drought tolerance | ABA synthesis | (Shi et al., 2020) |

| Vitis vinifera | DHN1/DHN2 | Cold-hardiness in dormant buds | ABA and low temperatures | (Rubio et al., 2019) |

Function and mechanism of LEA proteins regulated by ABA.

Figure 2

ABA-mediated regulation of LEA proteins in plant stress adaptation and developmental processes. The schematic illustrates the coordinated mechanisms through which plants respond to environmental stresses and developmental cues via ABA-mediated LEA protein expression. It highlights key functional roles of LEA proteins in stress adaptation, including responses to drought, salinity, cold, and osmotic stress, as well as their involvement in various developmental processes such as seed dormancy, germination, root growth, and leaf senescence. Arrows denote positive regulation, where solid lines depict well-defined pathways. The seed elements were created using BioGDP.

In Arabidopsis mutants deficient in ABA biosynthesis or signaling, the expression of LEA genes has been consistently down-regulated. Proteomic analysis showed a reduction in the expression levels of six out of eight LEA proteins in the embryos of the ABA-deficient mutant viviparous-5 (vp5) (Wu et al., 2014). The promoter activity of RAB17 is reduced in the ABA-deficient mutant aba1 compared to wild-type plants and ABA-insensitive mutants (Vilardell et al., 1994). Treatment with ABA or NaCl significantly induce RAB21 expression in rice (Mundy and Chua, 1988). Drought-induced expression of AtLEA5 requires ABA synthesis but is independent of ABI1 (Mowla et al., 2006). In Arabidopsis thaliana, exogenous ABA promotes RESPONSIVE TO ABA 18 (RAB18) mRNA accumulation (Lång and Palva, 1992). However, RAB18 expression is delayed in the ABA-insensitive mutant abi1 and completely absent in aba1 (Mantyla et al., 1995). Notably, RAB18 levels show no difference from the wild type in abi3 mutants, suggesting that RAB18 expression is ABA-dependent but independent of ABI3 (Nylander et al., 2001).

The expression of LEA proteins is regulated by the core ABA signaling pathway. In Arabidopsis lines overexpressing CsSnRK2.5 from tea plant (Camellia sinensis), ABA treatment and drought stress significantly elevated expression of stress-responsive genes (AtRAB18, AtRD29B) compared to wild-type plants (Zhang et al., 2020b). Similarly, Arabidopsis overexpressing grape ABSCISIC ACID RESPONSE ELEMENT-BINDING FACTOR2 (VvABF2) from Vitis vinifera showed upregulated expression of RAB18, DEHYDRIN LEA (LEA) and RESPONSIVE TO DESICCATION 29B (RD29B) following ABA treatment (Liu et al., 2019d). Conversely, the areb1 areb2 abf3 triple mutant exhibits downregulation of LEA genes (RD29B, RAB18, EM1, EM6) under dehydration, high salinity, or ABA treatment (Yoshida et al., 2010). Drought stress upregulated RESPONSIVE TO DESICCATION 29A (RD29A), RD29B, COLD-REGULATED 47 (COR47), RAB18, and RESPONSIVE TO DESICCATION 22 (RD22) in IbABF4-overexpressing Arabidopsis and sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) (Wang et al., 2019b). MYB DOMAIN PROTEIN 44 (MYB44) interacts with REGULATORY COMPONENT OF ABA RECEPTOR 1/PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE 1-LIKE 9 (RCAR1/PYL9) to attenuate ABI1 phosphatase inhibition, thereby negatively regulating RAB18 expression (Li et al., 2014a). Under salt stress, GhMYB73-overexpressing Arabidopsis shows elevated RD29B transcription. This effect may involve GhMYB73-PYL8 interaction modulating RD29B expression (Zhao et al., 2019). Arabidopsis LEA family members, including ABA-RESPONSIVE PROTEIN (ABR), are strongly induced by ABA, NaCl, and mannitol. ABR serves as a marker for ABA signaling and participates in ABI5-mediated leaf senescence (Tanaka et al., 2012; Su et al., 2016). Dehydrins contain SnRK2-specific phosphorylation sites. Notably, the ABA-nonactivated kinase SnRK2.10 phosphorylates Early Responsive to Dehydration 10 (ERD10) and ERD14 under osmotic stress (Maszkowska et al., 2019).

Emerging evidence indicates that multiple LEA proteins participate in abiotic stress responses through specific protein interactions. For example: in wheat, the dehydrin WZY2 (GenBank NO. EU395844) promoter contains ABRE, and WZY2 interacts with a PP2C phosphatase (XM_020293398). These features suggest WZY2 regulates abiotic stress-responsive genes via the ABA pathway (Zhu et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2019c). As a LEA family member, TaSMP1 interacts with ABI5 to modulate expression of the seed germination gene DOG1L1, thereby regulating seed dormancy and germination (Xu et al., 2025). In rice, the ABA-induced REPETITIVE PROLINE-RICH PROTEIN (RePRP) interacts with the cytoskeleton to facilitate adaptive root growth under stress conditions (Tseng et al., 2013; Hsiao et al., 2020). Furthermore, ABA signaling acts as a central hub for indirectly modulating LEA protein accumulation. ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 (HY5), a pivotal transcription factor in light signaling, promotes LEA genes expression by directly binding to the ABI5 promoter. This integration of light and ABA signaling enhances seedling tolerance to drought, salinity, and low temperature (Chen et al., 2008). DELAY OF GERMINATION 1 (DOG1), a key regulator of seed dormancy, induces LEA genes expression during seed development through ABI5-mediated regulation (Dekkers et al., 2016).

4.2 Multiple signaling pathways regulate LEA Proteins through ABA-mediated cross-talk

The expression of LEA genes is coordinately regulated by a sophisticated network, where ABA signaling serves as a central hub integrating diverse environmental and intracellular cues. Environmental signals, such as low temperature, initiate this regulatory network through synergistic interplay with ABA. Exogenous ABA application induces the expression of multiple cold stress-responsive dehydrin genes in Arabidopsis thaliana, with differential regulatory effects on distinct dehydrin subtypes (Guo et al., 1992; Rouse et al., 1996; Wang et al., 2014). This synergy is evident as ABA synthesis inhibitors block the low temperature induction of MfLEA3 (Shi et al., 2020), and combined ABA-cold treatment regulates the expression of VvDHN1 and VvDHN2 to enhance cold hardiness in grapevine (Rubio et al., 2019). This cross-talk is often mediated by key transcription factors. For instance, MsABF2 directly binds to the promoter of MsLEA-D34 to activate its expression (Lv et al., 2021), while DREB/CBF-type factors like VaCBF4 and OsDREB1F integrate ABA and stress signals, either directly or indirectly, to activate canonical ABA-responsive LEA genes such as RD29A, COR47, and RAB18 (Li et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2008).

Beyond environmental perception, intracellular second messengers, particularly calcium (Ca2+), form a critical layer of regulation. Stress-induced Ca2+ fluctuations are decoded by sensor proteins including Ca2+-dependent protein kinases (CPKs/CDPKs), calcineurin B-like protein complexes (CBL-CIPK), calmodulin-like proteins (CMLs), and calmodulins (CaMs) (Kudla et al., 2018), which subsequently regulate gene expression via MAPK cascades or transcription factors (Sun et al., 2021).

The CPK/CDPK branch acts as a central integrator, primarily by phosphorylating ABA signaling components. Arabidopsis CPK32 phosphorylates ABF4 to activate RD29A/RAB18 expression (Choi et al., 2005), while CPK4/11 target ABF1/ABF4 (Zhu et al., 2007), with cpk1 mutants showing impaired RD29A/COR15A expression (Huang et al., 2018a). The wheat TaCDPK9 module regulates ABA biosynthesis (Zhang et al., 2020a), establishing a feedback loop where CPK-phosphorylated ABFs drive LEA expression while LEA proteins modulate Ca2+ signaling through ABA homeostasis (Liu et al., 2022).

The CBL-CIPK module provides additional integration points. TaCIPK27 upregulates RD29B and other ABA-responsive genes (Wang et al., 2018), while CIPK3 mediates ABA-cold crosstalk for RD29B/RD29A induction and interacts with ABR1 to link Ca2+ and ABA signaling (Kim et al., 2003; Sanyal et al., 2017). CML20 functions as a negative regulator, with its mutation upregulating RAB18/COR47 expression (Wu et al., 2017).

MAPK cascades also regulate LEA genes, as demonstrated by reduced COR15A/RD29A in cold-stressed mpk3/mpk6 mutants (Li et al., 2017) and impaired RD29B/RAB18 induction in ABA-treated mkkk18 mutants (Mitula et al., 2015).

In conclusion, LEA expression is fine-tuned by a multi-layered regulatory network. This network seamlessly integrates direct environmental signals with intracellular second messengers (Ca2+) and kinase cascades (MAPK), with the ABA signaling pathway acting as the central backbone for this extensive cross-talk, ensuring a robust and adaptable stress response.

4.3 Feedback regulation of the ABA signaling by LEA proteins

Recent studies have revealed that LEA proteins are not merely passive effectors of ABA signaling but actively regulate the ABA pathway through feedback mechanisms (Table 5). Multiple LEA proteins (CaLEA1, LsEm1, and AtruLEA1) regulate stress responses through ABA sensitivity (Lim et al., 2015; Xiang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2025). These proteins participate in fine-tuning ABA accumulation and homeostasis. For example, Overexpression of the dehydrin TAS14 increases ABA accumulation in leaves during short-term stress (Muñoz-Mayor et al., 2012). LEA12OR stabilizes the STRESS/ABA-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE (SAPK10) under salt stress, promoting ABA biosynthesis and enhancing salt tolerance in rice (Ge et al., 2024). The LEA-like protein Salt Tolerance–Related Protein (STRP) regulates ABA sensitivity. The strp mutants exhibit defects in ABA responses, including germination, root growth, and stomatal closure, and show reduced expression of NINE-CIS-EPOXYCAROTENOID DIOXYGENASE 3 (NCED3) under salt stress (Fiorillo et al., 2020, 2023). OsLEA5 enhances drought tolerance by promoting ABA accumulation through upregulating ABA biosynthesis genes (NCED1, NCED5) and inhibiting ABA catabolism genes (ABA8ox2). It also interacts with ZINC FINGER PROTEIN 36 (ZFP36) to activate ABA-mediated antioxidant defense, improving drought and salt stress adaptation, and contributes to ABA-dependent seed germination inhibition (Huang et al., 2018b, 2018c).

Table 5

| Species | Names | Functions | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsicum annuum | LEA1 | Drought and salt stress | ABA signaling | (Lim et al., 2015) |

| Lactuca sativa | Em1 | Drought and salt stress | ABA signaling | (Xiang et al., 2018) |

| Acer truncatum | LEA1 | Drought and salt tolerance | ABA sensitivity | (Li et al., 2025) |

| Solanum lycopersicum | TAS14 | Drought and salt stress | ABA accumulation | (Muñoz-Mayor et al., 2012) |

| Oryza rufipogon | LEA12OR | Salt tolerance and yield | ABA synthesis | (Ge et al., 2024) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | STRP | Salt stress | ABA synthesis | (Fiorillo et al., 2020, 2023) |

| Oryza sativa | LEA5 | Antioxidant defense | ABA biosynthesis and ABA metabolism | (Huang et al., 2018c) |

| Oryza sativa | LEA5 | Seed germination | ABA signaling | (Huang et al., 2018b) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | LTI30 | drought stress | ABA sensitivity | (Shi et al., 2015) |

| Triticum aestivum | HVA1 | Drought and heat stress | ABA sensitivity | (Samtani et al., 2022) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | LEA14 | Drought stress | ABA signaling | (Li et al., 2014b) |

Function and mechanism of feedback regulation of ABA by LEA proteins.

Beyond their roles in ABA feedback regulation, distinct subgroups of LEA proteins extensively participate in plant adaptive responses to drought, salinity, and temperature stresses. They function by modulating ABA sensitivity or mediating the expression of downstream stress-related genes. The following research cases systematically reveal the multidimensional regulatory mechanisms of LEA proteins in ABA signaling transduction. LTI30, an Arabidopsis dehydrin from Group II LEA proteins, exemplifies this regulation. Knockout mutants of LTI30 show reduced sensitivity to ABA during seed germination, while overexpression lines show increased ABA sensitivity (Shi et al., 2015). Similarly, overexpression of the OsEm1 gene increases ABA sensitivity and upregulates the expression of other LEA genes, including RAB16A/C, RAB21, and LEA3 (Yu et al., 2016). In cotton, knockout of LEA3 (Gh_A08G0694) increases sensitivity to salt and drought stress and downregulates the expression of ABA/stress-related genes (Shiraku et al., 2022). Furthermore, HORDEUM VULGARE ALEURONE 1 (HVA1), a Group 3 LEA protein, enhances both drought resistance and heat tolerance through a dual regulatory network. Transgenic plants overexpressing HVA1 also display enhanced sensitivity to ABA (Samtani et al., 2022). Another study shows that overexpression of DHN, a member of the LEA protein family, upregulates genes involved in the ABA signaling pathway, such as RD22 and RD29B (Mota et al., 2019). Collectively, these findings establish LEA proteins as key regulators of plant stress resilience. They regulate ABA signaling cascades and modulate downstream stress-responsive gene networks.

Research demonstrates that LEA proteins indirectly regulate the ABA signaling pathway through protein-protein interaction networks (Dirk et al., 2020). Under drought stress, both AtLEA14-overexpressing lines and atpp2-b11 RNAi lines exhibit enhanced ABA sensitivity. The molecular mechanism likely involves AtLEA14 sequestering the AtPP2-B11 protein. This sequestration indirectly protects SnRK2 kinases from 26S proteasome-mediated degradation, ultimately promoting ABA signaling activation. This interaction reflects a synergistic inhibitory effect between LEA proteins and their partners during drought response (Li et al., 2014b; Cheng et al., 2017). Under salt stress conditions, both overexpression of the AtPP2-B11 F-BOX protein and overexpression of AtLEA14 significantly improve plant salt tolerance. Further investigations reveal that AtLEA14 maintains the structural stability of the AtPP2-B11 protein in saline environments. The stabilized AtPP2-B11 may then confer stress protection by specifically degrading transcription repressors that negatively regulate salt tolerance (Jia et al., 2014, 2015). Collectively, these findings unveil the molecular mechanism by which LEA proteins achieve environment-specific responses through dynamic protein interaction networks under distinct abiotic stresses, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Regulatory roles of LEA proteins in enhancing abiotic stress tolerance through ABA signaling modulation. LEA proteins function as core regulators in plant responses to abiotic stress. They enhance stress tolerance through three primary mechanisms: regulating ABA accumulation (LEA12OR, OsLEA5, TAS14), modulating ABA signaling (STRP, LTI30, OsEM1, HVA1, AtLEA14). By influencing ABA accumulation and amplifying ABA signaling, LEA proteins promote the activation of stress-responsive genes. These integrated actions collectively enhance plant stress tolerance through coordinated transcriptional reprogramming. Arrows denote positive regulation, where solid lines depict well-defined pathways.

5 Conclusions and future perspectives

This review synthesizes multi-source evidence to propose an “ABA-LEA positive feedback loop” model. According to this model, abiotic stresses, including drought, high salinity, and low temperature, activate the ABA signaling pathway and upregulate LEA expression. Beyond their conventional protective roles, LEA proteins function as active regulators that physically interact with core ABA signaling components, thereby amplifying the signal output to form a self-reinforcing circuit (Figure 4).

Figure 4

The crosstalk between LEA proteins and ABA under abiotic stress. When plants encounter drought, salinity, or osmotic stress, NCED gene expression is upregulated, enhancing ABA biosynthesis. The accumulated ABA is perceived by PYR/PYL/RCAR receptors, which inhibit PP2C phosphatase activity, thereby activating SnRK2 kinases. Activated SnRK2 phosphorylates bZIP transcription factors, enabling their binding to ABRE elements in LEA gene promoters and activating LEA expression. Subsequently, LEA proteins reinforce ABA signaling by upregulating NCED expression and modulating downstream stress-responsive networks, establishing a self-amplifying positive feedback loop that potentiates the plant’s stress adaptation. Arrows denote positive regulation, where solid lines depict well-defined pathways and dashed lines represent speculative relationships.

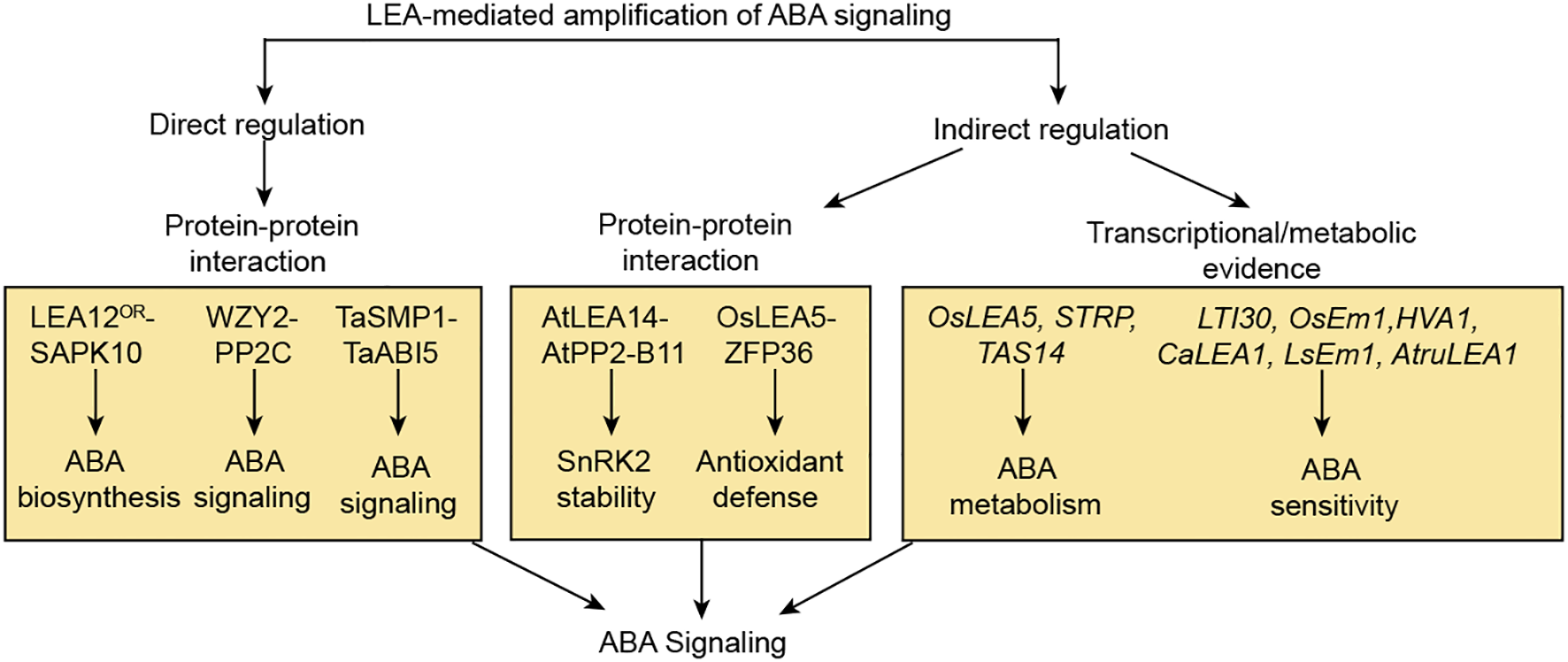

This review proposes an insightful “ABA-LEA positive feedback loop” model integrating traditional views with multi-source evidence. According to this model, abiotic stresses such as drought, high salinity, and low temperature activate the ABA signaling pathway, leading to upregulated LEA expression. Beyond their conventional protective roles, LEA proteins also function as active regulators that directly or indirectly interact with core ABA signaling components, thereby amplifying and sustaining ABA signal output and forming a self-reinforcing circuit (Figure 5). These include direct physical interactions with core ABA components such as PP2C phosphatases, SnRK2 kinases, and ABI5-like transcription factors, illustrated by WZY2-PP2C fine-tuning of ABA signaling in wheat, LEA12OR-SAPK10 stabilization promoting ABA biosynthesis, and TaSMP1-TaABI5 regulation of seed dormancy (Liu et al., 2019c; Ge et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2025). LEA proteins also engage in indirect modulation through interaction partners such as E3 ligases and zinc finger proteins, exemplified by AtLEA14 sequestering AtPP2-B11 to stabilize SnRK2 kinases under drought, OsLEA5 binding ZFP36 to enhance ABA-mediated antioxidant defense, and OsDhn-Rab16D interacting with OsFKBP to improve drought tolerance (Jia et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2018b, 2018c; Tiwari et al., 2019). Additionally, several LEA proteins, including OsLEA5, STRP, TAS14, LTI30, OsEm1, HVA1, CaLEA1, LsEm1, and AtruLEA1, modulate ABA sensitivity or accumulation, thereby influencing stress-related phenotypes (Huang et al., 2018c; Fiorillo et al., 2020, 2023; Muñoz-Mayor et al., 2012; Gupta et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2016; Samtani et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2015; Xiang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2025). Collectively, these interactions form a unified “bidirectional ABA-LEA regulatory network” model, wherein LEA proteins reinforce ABA signaling to ensure rapid and robust stress adaptation. By integrating multi-source evidence, this review provides novel insights into the functions and mechanisms of LEA proteins in plants, enhancing our understanding of the molecular basis of plant stress responses and their potential agricultural applications.

Figure 5

LEA proteins act as active regulators to amplify ABA signaling. This model summarizes the molecular evidence that LEA proteins act as active regulators to amplify ABA signaling. The amplification is achieved via three coordinated strategies: direct protein-protein interactions with core signaling components (LEA12OR-SAPK10, WZY2-PP2C, TaSMP1-TaABI5), indirect regulation through intermediary partners (AtLEA14-AtPP2-B11, OsLEA5-ZFP36), and the transcriptional and metabolic regulation of ABA homeostasis and sensitivity by OsLEA5, STRP, LTI30 and so on. Collectively, these LEA-driven mechanisms enhance ABA signaling, thereby forming a positive feedback loop that ensures a robust and sustained adaptive response to abiotic stress. Arrows denote positive regulation, where solid lines depict well-defined pathways.

The integration of LEA proteins and ABA signaling constitutes a central regulatory network in plant stress adaptation, where LEA members such as ZmDHN15 and OsLEA1a contribute to cellular redox homeostasis alongside their protective functions (Wang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022). This LEA-ABA feedback system further interfaces with ROS signaling and epigenetic reprogramming, reinforcing the perspective that ROS act as core elements of the epigenetic regulatory machinery (Kaya and Adamakis, 2025). Within this model, ABA-induced ROS fulfill dual and interconnected roles: they trigger immediate physiological responses such as stomatal closure (Postiglione and Muday, 2020) and drive persistent epigenetic changes, including DNA hypomethylation, which facilitates the activation of stress-responsive genes such as those encoding LEA proteins (Shi et al., 2017). The network is further reinforced as some LEA proteins, exemplified by OsLEA5, enhance ABA signaling and bolster antioxidant defenses (Huang et al., 2018c). Collectively, these interactions establish a “LEA-ABA-ROS-Epigenetic” axis, wherein ROS function as a dynamic hub linking rapid stress transduction to long-term transcriptional tuning via chromatin remodeling, thereby enhancing the plant’s adaptive capacity and stress memory.

Despite the promising potential of this model, its molecular mechanisms and broader biological implications require further systematic investigation. Current research remains largely focused on functionally characterizing LEA genes in a limited number of model plants, while a comprehensive understanding of their upstream regulatory networks and functional diversity across species and tissues is still lacking. To advance the field, future studies should prioritize the following three directions.

First, a deeper exploration of the molecular mechanisms governing the ABA-LEA interaction module is essential. Building on known interaction cases, systematic efforts should screen for direct interaction networks between LEA proteins and core ABA components, coupled with structural analyses of these complexes. The regulatory roles of post-translational modifications in LEA function warrant further investigation. For instance, elucidating whether CKII-mediated phosphorylation influences the nuclear localization and function of maize ZmDHN11 (Ju et al., 2021). Research should also examine the potential liquid-liquid phase separation behavior of LEA proteins during stress granule assembly, which could help distinguish their non-canonical regulatory roles from classical chaperone functions (Ginsawaeng et al., 2021; Hernández-Sánchez et al., 2022). Integrating live-cell imaging and single-molecule tracking to visualize the dynamic assembly of these modules in vivo will be crucial for confirming their physiological relevance. Furthermore, a critical yet under-explored area is the identification of mechanisms that attenuate or terminate the ABA-LEA positive feedback loop. While our model emphasizes signal amplification, any robust signaling system requires built-in “braking mechanisms” to prevent over-activation and ensure homeostasis. Future research should prioritize uncovering these negative regulatory circuits. Key questions include: How is LEA protein activity itself downregulated post-translationally? Are there specific E3 ubiquitin ligases or proteases that target regulatory LEA proteins for degradation upon stress relief? Does feedback inhibition from other hormone signaling pathways actively suppress the ABA-LEA axis to promote growth recovery? Elucidating these termination signals is not merely an addendum to the model but is fundamental to understanding the dynamic control and plasticity of plant stress responses, completing our holistic view of this regulatory network.

Second, research should expand to examine the evolutionary conservation and functional diversity of the ABA-LEA module. From a comparative and evolutionary perspective, the regulatory module linking ABA signaling to LEA protein expression is deeply conserved across land plants (Shinde et al., 2012). This conservation is observed in both monocots and dicots, where LEA gene promoters typically harbor ABA-responsive elements and show ABA-inducible expression (Liu et al., 2019b). Furthermore, key transcription factors such as ABI5 directly activate LEA genes, illustrating a shared regulatory logic (Su et al., 2016). Beyond this conserved framework, lineage-specific innovations have subsequently evolved. Monocots have expanded their LEA gene families (Zan et al., 2020) and developed novel protein interaction networks (Tiwari et al., 2019), enhancing their stress responsiveness. In contrast, dicots often integrate LEA proteins into broader developmental programs such as leaf senescence and flowering time (Su et al., 2016; Lv et al., 2021), highlighting divergent evolutionary strategies in adapting ABA-LEA signaling to distinct physiological contexts. Building upon this evolutionary foundation, a key future goal is to map the detailed landscape of these adaptations. Integrating cross-species comparative genomics with single-cell multi-omics data will help systematically analyze the conservation, lineage specificity, and tissue-specific expression patterns of this module across diverse plant groups (Battaglia and Covarrubias, 2013; Hernández-Sánchez et al., 2022). It is vital to clarify the functional differentiation of LEA subtypes among various cell types, tissues, and key physiological processes such as seed development, dormancy, and germination (Knox-Brown et al., 2020; Zamora-Briseño and de Jiménez, 2016).

Furthermore, elucidating the crosstalk between the ABA-LEA module and other key stress signaling pathways such as calcium signaling and MAPK cascades will be instrumental in constructing a more comprehensive plant stress response network. Calcium signaling acts as an independent second messenger system that engages in multi-level crosstalk with the ABA pathway, cooperatively regulating the expression of LEA and other stress-responsive genes. Similarly, core ABA signaling components can activate MAPK cascades, which fine-tune the expression of LEA through phosphorylation of ABA-responsive transcription factors (Sun et al., 2021). Although current evidence does not indicate that the ABA-LEA axis can directly feedback-regulate upstream elements such as calcium dynamics or MAPK activity, determining whether LEA proteins possess feedback or signal integration capabilities remains a critical research direction, to be addressed through multi-level approaches spanning protein interactions, transcriptional regulation, and epigenetics.

Third, translating the ABA-LEA module from theoretical concept to agricultural application represents a vital frontier. Building on existing overexpression studies-such as those demonstrating improved drought tolerance conferred by OsLEA3–1 or HVA1 (Xiao et al., 2007; Samtani et al., 2022), future work should develop synthetic biology strategies to rationally design LEA variants with enhanced interaction capacity or stability. CRISPR-based gene editing could also be employed to precisely modulate key nodes within this regulatory circuit, facilitating the development of novel crop germplasm with enhanced, conditionally regulated stress resilience. As most current studies rely on transgenic overexpression, strengthening reverse genetics validation using LEA knockout mutants (López-Cordova et al., 2021; Su et al., 2016) will provide a more robust theoretical foundation for breeding applications.

In summary, redefining LEA proteins as active regulatory components within the ABA represents a significant conceptual advance in plant stress biology. Through interdisciplinary integration of diverse research tools, systematic dissection and rational design of the ABA-LEA module will help bridge the gap from mechanistic insight to practical innovation, offering core technological drivers to address food security challenges under global climate change.

Statements

Author contributions

CH: Writing – original draft. XZ: Writing – original draft. NG: Writing – original draft. JL: Writing – review & editing. DC: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32370363), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2021QC210 and ZR2024MC219), and the Jinan Municipal Strategy Project for City-University Integrated Development (JNSX2024060).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Professor J.L. and Professor D.C. for their invaluable guidance and assistance throughout the research process. Their expertise and insights have been instrumental in shaping the direction of this work. We are thankful to all reviewers for their valuable input, which greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Battaglia M. Covarrubias A. A. (2013). Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) proteins in legumes. Front. Plant Sci.4. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00190

2

Battaglia M. Olvera-Carrillo Y. Garciarrubio A. Campos F. Covarrubias A. A. (2008). The enigmatic LEA proteins and other hydrophilins. Plant Physiol.148, 6–24. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.120725

3

Bojórquez-Velázquez E. Barrera-Pacheco A. Espitia-Rangel E. Herrera-Estrella A. Barba de la Rosa A. P. (2019). Protein analysis reveals differential accumulation of late embryogenesis abundant and storage proteins in seeds of wild and cultivated amaranth species. BMC Plant Biol.19. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1656-7

4

Borrell A. Cutanda M. C. Lumbreras V. Pujal J. Goday A. Culiáñez-Macià F. A. et al . (2002). Arabidopsis thaliana atrab28: a nuclear targeted protein related to germination and toxic cation tolerance. Plant Mol. Biol.50, 249–259. doi: 10.1023/a:1016084615014

5

Candat A. Paszkiewicz G. Neveu M. Gautier R. Logan D. C. Avelange-Macherel M. H. et al . (2014). The ubiquitous distribution of late embryogenesis abundant proteins across cell compartments in Arabidopsis offers tailored protection against abiotic stress. Plant Cell26, 3148–3166. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.127316

6

Carles C. Bies-Etheve N. Aspart L. Léon-Kloosterziel K. M. Koornneef M. Echeverria M. et al . (2002). Regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana Em genes: role of ABI5. Plant J.30, 373–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01295.x

7

Celik Altunoglu Y. Baloglu M. C. Baloglu P. Yer E. N. Kara S. (2017). Genome-wide identification and comparative expression analysis of LEA genes in watermelon and melon genomes. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants23, 5–21. doi: 10.1007/s12298-016-0405-8

8

Celik Altunoglu Y. Baloglu P. Yer E. N. Pekol S. Baloglu M. C. (2016). Identification and expression analysis of LEA gene family members in cucumber genome. Plant Growth Regul.80, 225–241. doi: 10.1007/s10725-016-0160-4

9

Charfeddine S. Saïdi M. N. Charfeddine M. Gargouri-Bouzid R. (2015). Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of the late embryogenesis abundant genes in potato with emphasis on dehydrins. Mol. Biol. Rep.42, 1163–1174. doi: 10.1007/s11033-015-3853-2

10

Chen N. Fan X. Wang C. Jiao P. Jiang Z. Ma Y. et al . (2022). Overexpression of ZmDHN15 enhances cold tolerance in yeast and Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 480. doi: 10.3390/ijms24010480

11

Chen R. Jiang H. Li L. Zhai Q. Qi L. Zhou W. et al . (2012). The Arabidopsis mediator subunit MED25 differentially regulates jasmonate and abscisic acid signaling through interacting with the MYC2 and ABI5 transcription factors. Plant Cell24, 2898–2916. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.098277

12

Chen J. Li N. Wang X. Meng X. Cui X. Chen Z. et al . (2021). Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) gene family in Salvia miltiorrhiza: identification, expression analysis, and response to drought stress. Plant Signal Behav.16, 1891769. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2021.1891769

13

Chen H. Zhang J. Neff M. M. Hong S. W. Zhang H. Deng X. W. et al . (2008). Integration of light and abscisic acid signaling during seed germination and early seedling development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.105, 4495–4500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710778105

14

Cheng C. Wang Z. Ren Z. Zhi L. Yao B. Su C. et al . (2017). SCFAtPP2-B11 modulates ABA signaling by facilitating SnRK2.3 degradation in Arabidopsis thaliana. PloS Genet.13, e1006947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006947

15

Choi H. I. Park H. J. Park J. H. Kim S. Im M. Y. Seo H. H. et al . (2005). Arabidopsis calcium-dependent protein kinase AtCPK32 interacts with ABF4, a transcriptional regulator of abscisic acid-responsive gene expression, and modulates its activity. Plant Physiol.139, 1750–1761. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.069757

16

Dekkers B. J. W. He H. Hanson J. Willems L. A. J. Jamar D. C. L. Cueff G. et al . (2016). The Arabidopsis DELAY OF GERMINATION 1 gene affects ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 5 (ABI5) expression and genetically interacts with ABI3 during Arabidopsis seed development. Plant J.85, 451–465. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13118

17

Ding M. Wang L. Zhan W. Sun G. Jia X. Chen S. et al . (2021). Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of late embryogenesis abundant protein-encoding genes in rye (Secale cereale L.). PloS One16, e0249757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249757

18

Dirk L. M. A. Abdel C. G. Ahmad I. Neta I. C. S. Pereira C. C. Pereira F. E. C. B. et al . (2020). Late embryogenesis abundant protein–client protein interactions. Plants9. doi: 10.3390/plants9070814

19

Du D. Zhang Q. Cheng T. Pan H. Yang W. Sun L. (2013). Genome-wide identification and analysis of late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) genes in Prunus mume. Mol. Biol. Rep.40, 1937–1946. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2250-3

20

Duan J. Cai W. (2012). OsLEA3-2, an abiotic stress induced gene of rice plays a key role in salt and drought tolerance. PloS One7, e45117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045117

21

Dure L. 3rd Greenway S. C. Galau G. A. (1981). Developmental biochemistry of cottonseed embryogenesis and germination: changing messenger ribonucleic acid populations as shown by in vitro and in vivo protein synthesis. Biochemistry20, 4162–4168. doi: 10.1021/bi00517a033

22

Fiorillo A. Manai M. Visconti S. Camoni L. (2023). The salt tolerance-related protein (STRP) is a positive regulator of the response to salt stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants (Basel)12. doi: 10.3390/plants12081704

23

Fiorillo A. Mattei M. Aducci P. Visconti S. Camoni L. (2020). The salt tolerance related protein (STRP) mediates cold stress responses and abscisic acid signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01251

24

Ge Y. Chen G. Cheng X. Li C. Tian Y. Chi W. et al . (2024). The superior allele LEA12(OR) in wild rice enhances salt tolerance and yield. Plant Biotechnol. J.22, 2971–2984. doi: 10.1111/pbi.14419

25

Ginsawaeng O. Heise C. Sangwan R. Karcher D. Hernández-Sánchez I. E. Sampathkumar A. et al . (2021). Subcellular localization of seed-expressed LEA_4 proteins reveals liquid-liquid phase separation for LEA9 and for LEA48 homo- and LEA42-LEA48 heterodimers. Biomolecules11. doi: 10.3390/biom11121770

26

Guo W. Ward R. W. Thomashow M. F. (1992). Characterization of a cold-regulated wheat gene related to Arabidopsis cor47. Plant Physiol.100, 915–922. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.2.915

27

Guo B. Zhang J. Yang C. Dong L. Ye H. Valliyodan B. et al . (2023). The late embryogenesis abundant proteins in soybean: identification, expression analysis, and the roles of GmLEA4_19 in drought stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24. doi: 10.3390/ijms241914834

28

Gupta A. Marzinek J. K. Jefferies D. Bond P. J. Harryson P. Wohland T. (2019). The disordered plant dehydrin Lti30 protects the membrane during water-related stress by cross-linking lipids. J. Biol. Chem.294, 6468–6482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.007163

29

Hernández-Sánchez I. E. Maruri-López I. Martinez-Martinez C. Janis B. Jiménez-Bremont J. F. Covarrubias A. A. et al . (2022). LEAfing through literature: late embryogenesis abundant proteins coming of age-achievements and perspectives. J. Exp. Bot.73, 6525–6546. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erac293

30

Hernández-Sánchez I. Rindfleisch T. Alpers J. Dulle M. Garvey C. J. Knox-Brown P. et al . (2024). Functional in vitro diversity of an intrinsically disordered plant protein during freeze-thawing is encoded by its structural plasticity. Protein Sci.33, e4989. doi: 10.1002/pro.4989

31

Hincha D. K. Thalhammer A. (2012). LEA proteins: IDPs with versatile functions in cellular dehydration tolerance. Biochem. Soc. Trans.40, 1000–1003. doi: 10.1042/bst20120109

32

Hsiao A.-S. (2024). Protein disorder in plant stress adaptation: from late embryogenesis abundant to other intrinsically disordered proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25. doi: 10.3390/ijms25021178

33

Hsiao A. S. Wang K. Ho T. D. (2020). An intrinsically disordered protein interacts with the cytoskeleton for adaptive root growth under stress. Plant Physiol.183, 570–587. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.01372

34

Hu M. Li Z. Lin X. Tang B. Xing M. Zhu H. (2024). Comparative analysis of the LEA gene family in seven Ipomoea species, focuses on sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.). BMC Plant Biol.24, 1256. doi: 10.1186/s12870-024-05981-x

35

Hu H. Xiong L. (2014). Genetic engineering and breeding of drought-resistant crops. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.65, 715–741. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040000

36

Huang L. Jia J. Zhao X. Zhang M. Huang X. Ji E. et al . (2018b). The ascorbate peroxidase APX1 is a direct target of a zinc finger transcription factor ZFP36 and a late embryogenesis abundant protein OsLEA5 interacts with ZFP36 to co-regulate OsAPX1 in seed germination in rice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.495, 339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.10.128

37

Huang K. Peng L. Liu Y. Yao R. Liu Z. Li X. et al . (2018a). Arabidopsis calcium-dependent protein kinase AtCPK1 plays a positive role in salt/drought-stress response. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.498, 92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.11.175

38

Huang R. Xiao D. Wang X. Zhan J. Wang A. He L. (2022). Genome-wide identification, evolutionary and expression analyses of LEA gene family in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). BMC Plant Biol.22, 155. doi: 10.1186/s12870-022-03462-7

39

Huang L. Zhang M. Jia J. Zhao X. Huang X. Ji E. et al . (2018c). An atypical late embryogenesis abundant protein OsLEA5 plays a positive role in ABA-induced antioxidant defense in Oryza sativa L. Plant Cell Physiol.59, 916–929. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy035

40

Huang Z. Zhong X. J. He J. Jin S. H. Guo H. D. Yu X. F. et al . (2016). Genome-wide identification, characterization, and stress-responsive expression profiling of genes encoding LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) proteins in Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). PloS One11, e0165953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165953

41

Hunault G. Jaspard E. (2010). LEAPdb: a database for the late embryogenesis abundant proteins. BMC Genomics11, 221. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-221

42

Hundertmark M. Dimova R. Lengefeld J. Seckler R. Hincha D. K. (2011). The intrinsically disordered late embryogenesis abundant protein LEA18 from Arabidopsis thaliana modulates membrane stability through binding and folding. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1808, 446–453. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.09.010

43

Hundertmark M. Hincha D. K. (2008). LEA (Late Embryogenesis Abundant) proteins and their encoding genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genomics9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-118

44

Jia C. Guo B. Wang B. Li X. Yang T. Li N. et al . (2022). The LEA gene family in tomato and its wild relatives: genome-wide identification, structural characterization, expression profiling, and role of SlLEA6 in drought stress. BMC Plant Biol.22, 596. doi: 10.1186/s12870-022-03953-7

45

Jia F. Qi S. Li H. Liu P. Li P. Wu C. et al . (2014). Overexpression of Late Embryogenesis Abundant 14 enhances Arabidopsis salt stress tolerance. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.454, 505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.136

46

Jia F. Wang C. Huang J. Yang G. Wu C. Zheng C. (2015). SCF E3 ligase PP2-B11 plays a positive role in response to salt stress in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot.66, 4683–4697. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv245

47

Ju H. Li D. Li D. Yang X. Liu Y. (2021). Overexpression of ZmDHN11 could enhance transgenic yeast and tobacco tolerance to osmotic stress. Plant Cell Rep.40, 1723–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00299-021-02734-0

48

Karpinska B. Razak N. Shaw D. S. Plumb W. Van De Slijke E. Stephens J. et al . (2022). Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA)5 regulates translation in mitochondria and chloroplasts to enhance growth and stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci.13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.875799

49

Kaya C. Adamakis I.-D. S. (2025). Redox-epigenetic crosstalk in plant stress responses: the roles of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in modulating chromatin dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci.26, 7167. doi: 10.3390/ijms26157167

50

Kim K. N. Cheong Y. H. Grant J. J. Pandey G. K. Luan S. (2003). CIPK3, a calcium sensor-associated protein kinase that regulates abscisic acid and cold signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell15, 411–423. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006858

51

Knox-Brown P. Rindfleisch T. Günther A. Balow K. Bremer A. Walther D. et al . (2020). Similar yet different–structural and functional diversity among Arabidopsis thaliana LEA_4 proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21. doi: 10.3390/ijms21082794

52

Koag M.-C. Wilkens S. Fenton R. D. Resnik J. Vo E. Close T. J. (2009). The K-segment of maize DHN1 mediates binding to anionic phospholipid vesicles and concomitant structural changes. Plant Physiol.150, 1503–1514. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.136697

53

Kosová K. Klíma M. Prášil I. T. Vítámvás P. (2021). COR/LEA proteins as indicators of frost tolerance in triticeae: a comparison of controlled versus field conditions. Plants10. doi: 10.3390/plants10040789

54

Kovacs D. Kalmar E. Torok Z. Tompa P. (2008). Chaperone activity of ERD10 and ERD14, two disordered stress-related plant proteins. Plant Physiol.147, 381–390. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.118208

55

Kudla J. Becker D. Grill E. Hedrich R. Hippler M. Kummer U. et al . (2018). Advances and current challenges in calcium signaling. New Phytol.218, 414–431. doi: 10.1111/nph.14966

56

Lång V. Palva E. T. (1992). The expression of a rab-related gene, rab18, is induced by abscisic acid during the cold acclimation process of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Plant Mol. Biol.20, 951–962. doi: 10.1007/bf00027165

57

Leprince O. Pellizzaro A. Berriri S. Buitink J. (2017). Late seed maturation: drying without dying. J. Exp. Bot.68, 827–841. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw363

58

Li H. Ding Y. Shi Y. Zhang X. Zhang S. Gong Z. et al . (2017). MPK3- and MPK6-mediated ICE1 phosphorylation negatively regulates ICE1 stability and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell43, 630–642.e634. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.09.025

59

Li Y. Jia F. Yu Y. Luo L. Huang J. Yang G. et al . (2014b). The SCF E3 ligase AtPP2-B11 plays a negative role in response to drought stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep.32, 943–956. doi: 10.1007/s11105-014-0705-5

60

Li D. Li Y. Zhang L. Wang X. Zhao Z. Tao Z. et al . (2014a). Arabidopsis ABA receptor RCAR1/PYL9 interacts with an R2R3-type MYB transcription factor, AtMYB44. Int. J. Mol. Sci.15, 8473–8490. doi: 10.3390/ijms15058473

61

Li S. Meng H. Yang Y. Zhao J. Xia Y. Wang S. et al . (2025). Overexpression of AtruLEA1 from Acer truncatum bunge enhanced Arabidopsis drought and salt tolerance by improving ROS-scavenging capability. Plants (Basel)14. doi: 10.3390/plants14010117

62

Li Q. Wang M. Fang L. (2021). BASIC PENTACYSTEINE2 negatively regulates osmotic stress tolerance by modulating LEA4–5 expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Biochem.168, 373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.10.030

63

Li J. Wang N. Xin H. Li S. (2013). Overexpression of VaCBF4, a transcription factor from Vitis amurensis, improves cold tolerance accompanying increased resistance to drought and salinity in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep.31, 1518–1528. doi: 10.1007/s11105-013-0627-7

64

Li S. Wuyun T. N. Wang L. Zhang J. Tian H. Zhang Y. et al . (2024). Genome-wide and functional analysis of late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) genes during dormancy and sprouting periods of kernel consumption apricots (P. Armeniaca L. × P. sibirica L.). Int. J. Biol. Macromol279, 133245. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133245

65

Lim C. W. Lim S. Baek W. Lee S. C. (2015). The pepper late embryogenesis abundant protein CaLEA1 acts in regulating abscisic acid signaling, drought and salt stress response. Physiol. Plant154, 526–542. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12298

66

Lim J. Lim C. W. Lee S. C. (2018). The pepper late embryogenesis abundant protein, CaDIL1, positively regulates drought tolerance and ABA signaling. Front. Plant Sci.9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01301

67

Ling H. Zeng X. Guo S. (2016). Functional insights into the late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) protein family from Dendrobium officinale (Orchidaceae) using an Escherichia coli system. Sci. Rep.6, 39693. doi: 10.1038/srep39693

68

Liu J. Chu J. Ma C. Jiang Y. Ma Y. Xiong J. et al . (2019d). Overexpression of an ABA-dependent grapevine bZIP transcription factor, VvABF2, enhances osmotic stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep.38, 587–596. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02389-y

69

Liu H. Song S. Zhang H. Li Y. Niu L. Zhang J. et al . (2022). Signaling transduction of ABA, ROS, and Ca2+ in plant stomatal closure in response to drought. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 14824. doi: 10.3390/ijms232314824

70

Liu D. Sun J. Zhu D. Lyu G. Zhang C. Liu J. et al . (2019a). Genome-wide identification and expression profiles of late embryogenesis-abundant (LEA) genes during grain maturation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Genes10. doi: 10.3390/genes10090696

71

Liu H. Xing M. Yang W. Mu X. Wang X. Lu F. et al . (2019b). Genome-wide identification of and functional insights into the late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) gene family in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum). Sci. Rep.9, 13375. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49759-w

72

Liu H. Yang Y. Zhang L. (2019c). Identification of upstream transcription factors and an interacting PP2C protein of dehydrin WZY2 gene in wheat. Plant Signal Behav.14, 1678370. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2019.1678370

73

Liu Q. Zheng L. Wang Y. Zhou Y. Gao F. (2024). AmDHN4, a winter accumulated SKn-type dehydrin from Ammopiptanthus mongolicus, and regulated by AmWRKY45, enhances the tolerance of Arabidopsis to low temperature and osmotic stress. Int. J. Biol. Macromol266, 131020. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131020

74

López-Cordova A. Ramírez-Medina H. Silva-Martinez G. A. González-Cruz L. Bernardino-Nicanor A. Huanca-Mamani W. et al . (2021). LEA13 and LEA30 are involved in tolerance to water stress and stomata density in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants (Basel)10. doi: 10.3390/plants10081694

75

Lv A. Su L. Wen W. Fan N. Zhou P. An Y. (2021). Analysis of the function of the Alfalfa Mslea-D34 gene in abiotic stress responses and flowering time. Plant Cell Physiol.62, 28–42. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcaa121

76

Mantyla E. Lang V. Palva E. T. (1995). Role of abscisic acid in drought-induced freezing tolerance, cold acclimation, and accumulation of LT178 and RAB18 proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol.107, 141–148. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.1.141

77

Maszkowska J. Debski J. Kulik A. Kistowski M. Bucholc M. Lichocka M. et al . (2019). Phosphoproteomic analysis reveals that dehydrins ERD10 and ERD14 are phosphorylated by SNF1-related protein kinase 2.10 in response to osmotic stress. Plant Cell Environ.42, 931–946. doi: 10.1111/pce.13465

78

Mitula F. Tajdel M. Cieśla A. Kasprowicz-Maluśki A. Kulik A. Babula-Skowrońska D. et al . (2015). Arabidopsis ABA-activated kinase MAPKKK18 is regulated by protein phosphatase 2C ABI1 and the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Plant Cell Physiol.56, 2351–2367. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv146

79

Mota A. P. Z. Oliveira T. N. Vinson C. C. Williams T. C. R. Costa M. Araujo A. C. G. et al . (2019). Contrasting effects of wild Arachis dehydrin under abiotic and biotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00497

80

Mowla S. B. Cuypers A. Driscoll S. P. Kiddle G. Thomson J. Foyer C. H. et al . (2006). Yeast complementation reveals a role for an Arabidopsis thaliana late embryogenesis abundant (LEA)-like protein in oxidative stress tolerance. Plant J.48, 743–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02911.x

81

Müller H. M. Schäfer N. Bauer H. Geiger D. Lautner S. Fromm J. et al . (2017). The desert plant Phoenix dactylifera closes stomata via nitrate-regulated SLAC1 anion channel. New Phytol.216, 150–162. doi: 10.1111/nph.14672

82

Mundy J. Chua N. H. (1988). Abscisic acid and water-stress induce the expression of a novel rice gene. EMBO J.7, 2279–2286. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03070.x

83

Muñoz-Mayor A. Pineda B. Garcia-Abellán J. O. Antón T. Garcia-Sogo B. Sanchez-Bel P. et al . (2012). Overexpression of dehydrin tas14 gene improves the osmotic stress imposed by drought and salinity in tomato. J. Plant Physiol.169, 459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.11.018

84

Nagaraju M. Kumar S. A. Reddy P. S. Kumar A. Rao D. M. Kavi Kishor P. B. (2019). Genome-scale identification, classification, and tissue specific expression analysis of late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) genes under abiotic stress conditions in Sorghum bicolor L. PloS One14, e0209980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209980

85

Navarro-Retamal C. Bremer A. Ingólfsson H. I. Alzate-Morales J. Caballero J. Thalhammer A. et al . (2018). Folding and lipid composition determine membrane interaction of the disordered protein COR15A. Biophys. J.115, 968–980. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.08.014

86

Nylander M. Svensson J. Palva E. T. Welin B. V. (2001). Stress-induced accumulation and tissue-specific localization of dehydrins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol.45, 263–279. doi: 10.1023/a:1006469128280

87

Olvera-Carrillo Y. Campos F. Reyes J. L. Garciarrubio A. Covarrubias A. A. (2010). Functional analysis of the group 4 late embryogenesis abundant proteins reveals their relevance in the adaptive response during water deficit in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol.154, 373–390. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.158964

88

Pedrosa A. M. Martins Cde P. Gonçalves L. P. Costa M. G. (2015). Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) constitutes a large and diverse family of proteins involved in development and abiotic stress responses in sweet orange (Citrus sinensis L. Osb.). PloS One10, e0145785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145785

89

Postiglione A. E. Muday G. K. (2020). The role of ROS homeostasis in ABA-induced guard cell signaling. Front. Plant Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00968

90

Rendón-Luna D. F. Arroyo-Mosso I. A. De Luna-Valenciano H. Campos F. Segovia L. Saab-Rincón G. et al . (2024). Alternative conformations of a group 4 Late Embryogenesis Abundant protein associated to its in vitro protective activity. Sci. Rep.14, 2770. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-53295-7

91

Riera M. Figueras M. López C. Goday A. Pagès M. (2004). Protein kinase CK2 modulates developmental functions of the abscisic acid responsive protein Rab17 from maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.101, 9879–9884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306154101

92

Rouse D. T. Marotta R. Parish R. W. (1996). Promoter and expression studies on an Arabidopsis thaliana dehydrin gene. FEBS Lett.381, 252–256. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00051-8

93

Rubio S. Noriega X. Perez F. J. (2019). Abscisic acid (ABA) and low temperatures synergistically increase the expression of CBF/DREB1 transcription factors and cold-hardiness in grapevine dormant buds. Ann. Bot.123, 681–689. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcy201

94

Samtani H. Sharma A. Khurana P. (2022). Overexpression of HVA1 enhances drought and heat stress tolerance in Triticum aestivum doubled haploid plants. Cells11. doi: 10.3390/cells11050912

95

Sanyal S. K. Kanwar P. Yadav A. K. Sharma C. Kumar A. Pandey G. K. (2017). Arabidopsis CBL interacting protein kinase 3 interacts with ABR1, an APETALA2 domain transcription factor, to regulate ABA responses. Plant Sci.254, 48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.11.004

96

Shi H. Chen Y. Qian Y. Chan Z. (2015). Low Temperature-Induced 30 (LTI30) positively regulates drought stress resistance in Arabidopsis: effect on abscisic acid sensitivity and hydrogen peroxide accumulation. Front. Plant Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00893

97

Shi H. He X. Zhao Y. Lu S. Guo Z. (2020). Constitutive expression of a group 3 LEA protein from Medicago falcata (MfLEA3) increases cold and drought tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Rep.39, 851–860. doi: 10.1007/s00299-020-02534-y

98

Shi D. Zhuang K. Xia Y. Zhu C. Chen C. Hu Z. et al . (2017). Hydrilla verticillata employs two different ways to affect DNA methylation under excess copper stress. Aquat Toxicol.193, 97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.10.007

99

Shinde S. Nurul Islam M. Ng C. K. (2012). Dehydration stress-induced oscillations in LEA protein transcripts involves abscisic acid in the moss, Physcomitrella patens. New Phytol.195, 321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04193.x

100

Shiraku M. L. Magwanga R. O. Zhang Y. Hou Y. Kirungu J. N. Mehari T. G. et al . (2022). Late embryogenesis abundant gene LEA3 (Gh_A08G0694) enhances drought and salt stress tolerance in cotton. Int. J. Biol. Macromol207, 700–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.03.110

101

Su M. Huang G. Zhang Q. Wang X. Li C. Tao Y. et al . (2016). The LEA protein, ABR, is regulated by ABI5 and involved in dark-induced leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci.247, 93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.03.009

102

Sun Z. Li S. Chen W. Zhang J. Zhang L. Sun W. et al . (2021). Plant dehydrins: expression, regulatory networks, and protective roles in plants challenged by abiotic stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22. doi: 10.3390/ijms222312619

103

Szlachtowska Z. Rurek M. (2023). Plant dehydrins and dehydrin-like proteins: characterization and participation in abiotic stress response. Front. Plant Sci.14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1213188

104

Tanaka H. Osakabe Y. Katsura S. Mizuno S. Maruyama K. Kusakabe K. et al . (2012). Abiotic stress-inducible receptor-like kinases negatively control ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant J.70, 599–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04901.x

105

Thalhammer A. Hundertmark M. Popova A. V. Seckler R. Hincha D. K. (2010). Interaction of two intrinsically disordered plant stress proteins (COR15A and COR15B) with lipid membranes in the dry state. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1798, 1812–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.05.015

106

Tiwari P. Indoliya Y. Singh P. K. Singh P. C. Chauhan P. S. Pande V. et al . (2019). Role of dehydrin-FK506-binding protein complex in enhancing drought tolerance through the ABA-mediated signaling pathway. Environ. Exp. Bot.158, 136–149. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.10.031

107

Tseng I. C. Hong C. Y. Yu S. M. Ho T. H. (2013). Abscisic acid- and stress-induced highly proline-rich glycoproteins regulate root growth in rice. Plant Physiol.163, 118–134. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.217547

108

Vilardell J. Martínez-Zapater J. M. Goday A. Arenas C. Pagès M. (1994). Regulation of the rab17 gene promoter in transgenic Arabidopsis wild-type, ABA-deficient and ABA-insensitive mutants. Plant Mol. Biol.24, 561–569. doi: 10.1007/bf00023554

109

Waadt R. Seller C. A. Hsu P. K. Takahashi Y. Munemasa S. Schroeder J. I. (2022). Plant hormone regulation of abiotic stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.23, 680–694. doi: 10.1038/s41580-022-00479-6

110