- 1College of Plant Science, Xizang Agricultural and Animal Husbandry University, Nyingchi, Xizang Autonomous Region, China

- 2School of Resources and Environmental Engineering, Moutai Institute, Renhuai, Guizhou, China

- 3School of Brewing Engineering, Moutai Institute, Renhuai, Guizhou, China

- 4College of Forestry and Grassland, Xizang Agricultural and Animal Husbandry University, Nyingchi, Xizang Autonomous Region, China

Botrytis cinerea is a necrotrophic fungal pathogen that causes significant crop damage, yet the molecular mechanisms underlying plant defense remain incompletely understood. Here, we identify WRKY45 as a negative regulator of Arabidopsis resistance to B. cinerea through the suppression of JA/ET-mediated defense signaling. Our results show that WRKY45 expression was induced by B. cinerea infection, peaking 48 hours post-inoculation. Loss of WRKY45 function enhanced resistance, while WRKY45 overexpression increased susceptibility and cellular damage, as indicated by elevated electrolyte leakage, higher malondialdehyde levels, and reduced chlorophyll content. RNA-seq analysis identified 1,850 differentially expressed genes in wrky45 mutants, with strong enrichment of JA/ET-responsive pathways. Defense-related genes, including ORA59, PDF1.2, ERF104, and ERF1, were markedly upregulated in wrky45 but suppressed in overexpression lines, as confirmed by qRT-PCR. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays and dual-luciferase assays demonstrated that WRKY45 directly binds to the ORA59 promoter inhibiting its transcription, and represses the expression of PDF1.2, ERF104, and ERF1. Together, these results show that WRKY45 functions as a negative regulator by suppressing the expression of JA/ET-mediated defense genes, thereby modulating plant resistance to B. cinerea.

1 Introduction

Necrotrophic fungal pathogens are a major threat to global agriculture by inducing host cell death and colonizing necrotic tissues as nutrient sources. Their airborne dissemination further accelerates disease spread. Among them, B. cinerea infects over 200 plant species and causes severe pre- and post-harvest losses worldwide (Dean et al., 2012; van Kan, 2006; Bi et al., 2021). Although jasmonic acid (JA), ethylene (ET), and salicylic acid (SA) signaling pathways are known to orchestrate plant immune responses (Glazebrook, 2005; AbuQamar et al., 2017; Song et al., 2022), the transcriptional regulatory frameworks that integrate these signals and orchestrate robust immunity against necrotrophs are still not fully understood.

In Arabidopsis, the JA/ET signaling module plays a pivotal role in resistance to B. cinerea. Core defense-associated genes, including ORA59, PDF1.2, ERF104, and ERF1, function as critical hubs within this pathway, integrating hormonal cues and activating antimicrobial responses. ORA59 functions as a central integrator of the JA and ET signaling pathways (Pré et al., 2008; Ju et al., 2017), whereas PDF1.2 encodes a plant defensin that serves as a hallmark of JA/ET-mediated defense (Penninckx et al., 1996; Cheng et al., 2018). ERF104 is an ET-responsive factor, and related studies indicate that it plays a crucial role in resisting non-adapted pathogens (Chen et al., 2013). ERF1 amplifies resistance by coordinating a broad spectrum of JA/ET-dependent defense programs (Lorenzo et al., 2003; Rasool et al., 2015). The activities of these JA/ET-responsive genes are strongly shaped by upstream transcription factors, highlighting the importance of transcriptional regulation in controlling immune outputs.

Among transcription factors, WRKY proteins have emerged as master regulators of plant immunity. They constitute one of the largest transcription factor families in plants and exert diverse functions by binding to W-box cis-elements in target promoters (Chen et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2022). WRKY transcription factors act as critical regulators of stress responses, functioning either as activators or repressors of defense genes to fine-tune plant immunity (Wang et al., 2025; Chen et al., 2025; Du et al., 2023). For example, WRKY33 is a well-characterized positive regulator of resistance to B. cinerea, enhancing JA/ET signaling, reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis, and secondary metabolism (Birkenbihl et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2015). WRKY75 similarly promotes JA-mediated immunity (Chen et al., 2021). OsWRKY67 positively regulates plant disease resistance through the modulation of defense-related genes (Liu et al., 2018). contrast, several WRKYs—including SlWRKY3, PtrWRKY89, and VqWRKY52—function as negative regulators to prevent excessive immune activation (Luo et al., 2024; Jiang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017). These functional divergences highlight the context-dependent nature of WRKY function in plant immunity.

WRKY45 is a member of the WRKY transcription factor family and has been reported to participate in various physiological processes in Arabidopsis, such as responses to phosphorus starvation, salt stress, cadmium toxicity, and leaf senescence (Wang et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2025; Li et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2017; Vatov et al., 2021; Barros et al., 2022). However, its role in plant immunity remains poorly understood, particularly in defense against necrotrophic pathogens. Considering the dual regulatory roles of WRKY transcription factors and the central importance of JA/ET-regulated defense genes such as ORA59, PDF1.2, Thi2.1, and ERF1, elucidating the function of WRKY45 in Arabidopsis immunity against B. cinerea is critical.

In this study, we investigate the role of WRKY45 in modulating Arabidopsis resistance to B. cinerea. We specifically assess whether WRKY45 regulates key JA/ET-dependent defense genes and dissect the transcriptional mechanisms underlying its activity. Our findings demonstrate that WRKY45 functions as a negative regulator of plant immunity, thereby providing new insights into the transcriptional networks shaping host responses to necrotrophic pathogens and offering potential targets for enhance disease resistance in crops.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant materials and growth conditions

The experimental materials included Arabidopsis (Columbia ecotype, Col-0 wild type), as well as wrky45 mutant lines (WRKY45-RNAI-3 and wrky45) (Wang et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2017), and WRKY45 overexpression lines (35S:WRKY45–2 and 35S:WRKY45-6). Seeds of Arabidopsis were surface-sterilized with 20% bleach solution for 15 minutes, and then sown on half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) solid medium (pH 5.8). After stratification at 4°C for 3 days, the plates were transferred to a greenhouse under a 16-hour light/8-hour dark photoperiod at 22°C. After 7 days of growth, seedlings were transplanted into moist soil and covered with plastic film, which was removed after 2–3 days to allow further growth. Seeds of Nicotiana benthamiana were grown in a green house at 25°C under a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod. In all experiments, Arabidopsis seedlings used for B. cinerea inoculation were consistently two weeks old. The WRKY45 overexpression lines were constructed and maintained at the Key Laboratory of Sustainable Utilization of Tropical Plant Resources, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Verification of the WRKY45 overexpression lines (35S:WRKY45–2 and 35S:WRKY45-6) is provided in Supplementary Figure 1.

2.2 Pathogen inoculation with B. cinerea

B. cinerea strain B05.10 was cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 22°C under a 12-hour light/12-hour dark photoperiod (Xiang et al., 2020). For whole-plant inoculation, B. cinerea conidial suspension was evenly sprayed onto the leaves of 2-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings, which were then maintained under short-day, high-humidity, and dark conditions to promote infection (Scholz et al., 2023). Samples were collected at 0 and 5 days post-inoculation (dpi) for physiological measurements, and disease symptoms were monitored daily. For detached leaf inoculation, B. cinerea conidia were suspended in SMB (40 g/L maltose, 10 g/L peptone) with 0.1% Tween 80, and the suspension was filtered through gauze to obtain a conidial solution. A 3 μL droplet of this suspension (5 × 105; spores/mL) was applied to the abaxial surface of 14-day-old soil-grown Arabidopsis leaves, with 3 μL of SMB solution as a control. The leaves were placed on moist filter paper in Petri dishes and incubated under low light and high humidity at 22 °C for 3 days. Disease symptoms were assessed, and qualitative evaluation was performed using GUS staining.

2.3 RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Seeds of Arabidopsis (different genotypes) were germinated on half-strength Murashige and Skoog solid medium, stratified at 4°C for 3 days and grown for 7 days before transferring to moist soil for 2 weeks. Seedlings were then inoculated with B. cinerea, and samples were harvested at various time points post-inoculation. Total RNA was extracted from Arabidopsis seedlings using the water-saturated phenol method. First-strand cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription, followed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT–PCR). Reverse transcription and qRT–PCR kits were obtained from Takara (Dalian, China), and PCR was performed on a QuantStudio 5 real-time PCR machine using SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ II. ACTIN2 (AT3G18780) was used as internal control in qRT–PCR. Primer sequences used in qRT–PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

2.4 RNA sequencing

Wild-type and wrky45 mutant Arabidopsis lines, grown for two weeks, were inoculated with a suspension of B. cinerea spores and maintained under treatment conditions for five days. Samples were collected from both WT and wrky45 mutant plants before and after inoculation. Total RNA was extracted from the seedlings using the water-saturated phenol method and subsequently sent to Kunming Hengyun Biotechnology Co., Ltd. for transcriptome sequencing. Three independent biological replicates were analyzed for each condition.

2.5 GUS staining

Histochemical GUS assays were performed as described previously (Chen et al., 2021). The GUS staining kit was purchased from Zhongke Ruitai Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Fourteen-day-old WRKY45p:GUS transgenic seedlings were detached and inoculated with B. cinerea for three days before GUS staining. Tissues were decolorized in 70% ethanol, with the solution replaced two to three times until the control tissues became completely white, and then photographed. Three independent biological replicates were processed under identical staining and imaging conditions to ensure reproducibility.

2.6 Electrolyte leakage assay

Electrolyte leakage was measured to assess membrane integrity in wild-type, wrky45 mutant, and WRKY45 overexpression seedlings at 0 and 5 dpi. Leaves were immersed in 10 mL of deionized water and gently shaken before measuring the initial conductivity (R0). Samples were then incubated at room temperature for 2 hours to allow passive ion leakage, and conductivity was measured again (R1). Subsequently, samples were boiled at 100°C for 20 minutes, cooled to room temperature, and final conductivity (R2) was measured. Electrolyte leakage was calculated as (R1 − R0)/(R2 − R0) × 100, following Bajji (Bajji et al., 2002). Three independent biological replicates were analyzed for each genotype.

2.7 Chlorophyll quantification

Fully expanded Arabidopsis leaves were collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground to a fine powder. Photosynthetic pigments were extracted using ice-cold 80% (v/v) acetone, followed by centrifugation to remove debris. The Absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 663 nm and 645 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer. Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll contents were calculated using the Lichtenthaler equations for 80% acetone (Lichtenthaler, 1987). Three independent biological replicates were analyzed for each genotype.

2.8 Determination of malondialdehyde content

Malondialdehyde (MDA) content was determined using a thiobarbituric acid (TBA) method. Samples were collected from wild-type, mutant, and WRKY45-overexpressing Arabidopsis seedlings before and after B. cinerea infection. Approximately 1 g of fresh tissue was weighed, cut into small pieces and homogenized in 10 mL of 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) using a mortar and pestle. The homogenate was centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 10 min, and 6 mL of the supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of 0.6% (w/v) thiobarbituric acid solution. The mixture was incubated in a boiling water bath at 100 °C for 15 min, rapidly cooled to room temperature, and centrifuged for 1 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 450, 532, and 600 nm using a spectrophotometer, with 2 mL of distilled water as the blank control. MDA content was calculated according to the method described by Huang (Huang et al., 2016). Three independent biological replicates were analyzed for each genotype.

2.9 Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

To examine the potential interaction between WRKY45 and the W-box element, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed using a chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA fragments corresponding to the ORA59 promoter region, containing either the wild-type W-box sequence or a mutated W-box motif, were synthesized and end-labeled with biotin. Purified recombinant GST-WRKY45 fusion protein was incubated with the labeled probes in binding buffer at room temperature for 20 minutes. For competition assays, a 50- to 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled probe was added in the reaction. The DNA–protein complexes were separated on 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels and subsequently transferred to nylon membranes (Brunello et al., 2024). Biotin-labeled DNA was detected according to the kit protocol. The primers used for the EMSA assay are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

2.10 Transcriptional activity assays

The native promoters (about 2.5 kb) of ORA59, PDF1.2, ERF1, and ERF104 were cloned into pGWB35 to generate the reporter constructs ORA59p:LUC, PDF1.2p:LUC, ERF1p:LUC, and ERF104p:LUC using Gateway technology (Invitrogen, USA). The reporter plasmids and effector constructs carrying 35S:WRKY45 were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 (pSoup). Agrobacterium cultures harboring the respective plasmids were grown, collected, and resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, and 200 μM acetosyringone) to an OD600 of 0.6 prior to infiltration (Kang et al., 2023). After infiltration, plants were maintained in a growth chamber under high humidity and low-light conditions for 72 hours. Before luminescence imaging, the infiltrated leaves were sprayed with fluorescein potassium salt solution (10 mL sterilized water + 10 μL 10% Triton X-100 + 0.008 g fluorescein potassium salt), incubated in the dark for 5 minutes, and imaged using a cooled CCD imaging system (Olympus, Japan) to capture LUC luminescence (Zhang et al., 2022). Each experiment was performed with at least three independent biological replicates. The primers used for the transcriptional activity assays are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

2.11 Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed with at least three independent biological replicates, and data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way ANOVA was used for Figure 1A, a two-tailed Student’s t-test for Figure 2E, and two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test for Figures 3, 5. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among multiple groups, while asterisks (* or **) denote significant differences in pairwise comparisons (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

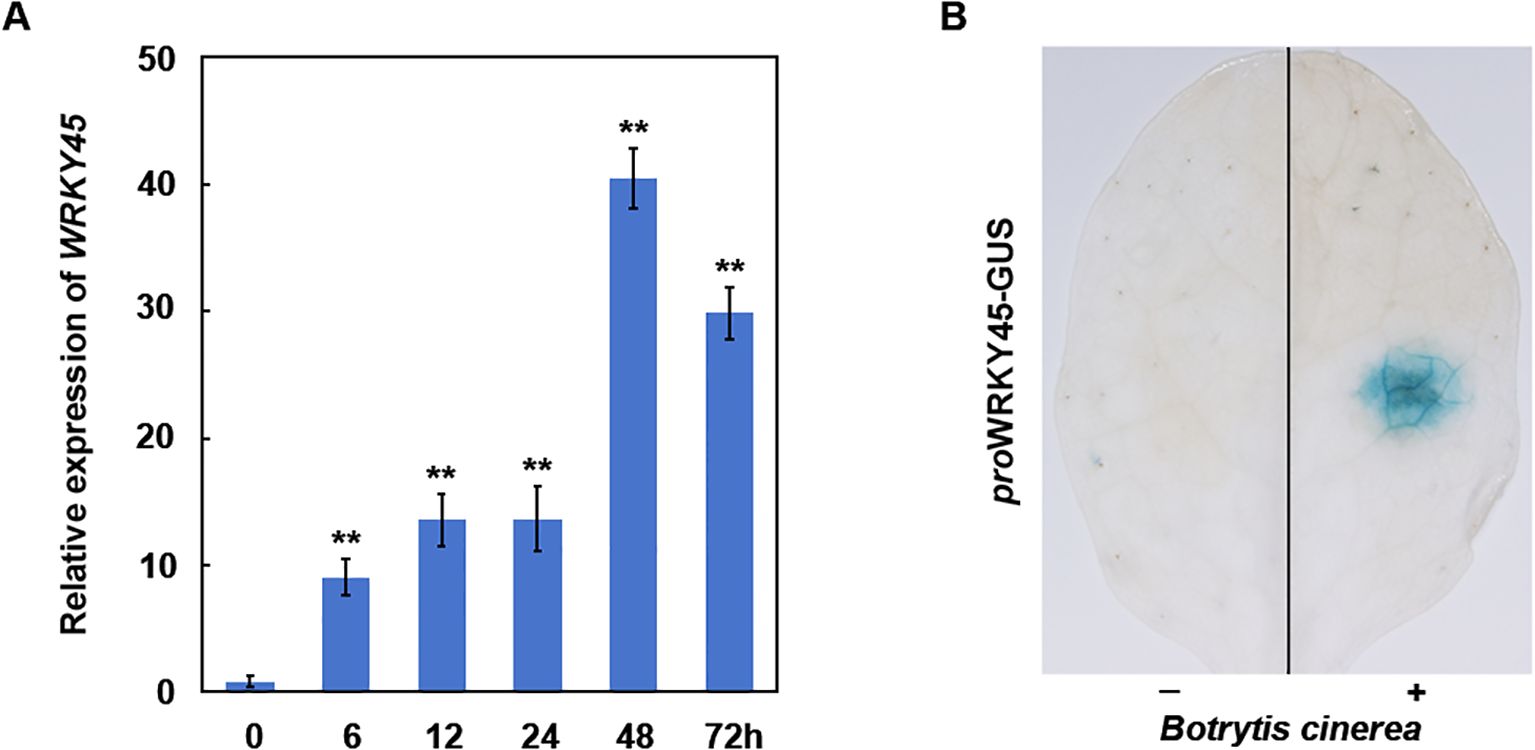

Figure 1. WRKY45 expression is induced by B. cinerea. (A) Time-course analysis of WRKY45 transcript accumulation in Arabidopsis following inoculation with (B) cinerea. Relative expression levels were quantified by qRT–PCR at 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours post-inoculation (hpi), using ACTIN2 as the internal reference gene. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 independent biological replicates). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA, and asterisks indicate significant differences compared to 0 h (**P < 0.01). (B) Histochemical GUS staining of WRKY45p:GUS transgenic plants after B. cinerea inoculation. Strong GUS activity was observed at the inoculation sites (+), compared to untreated control sites (–), confirming local induction of WRKY45 expression by pathogen infection.

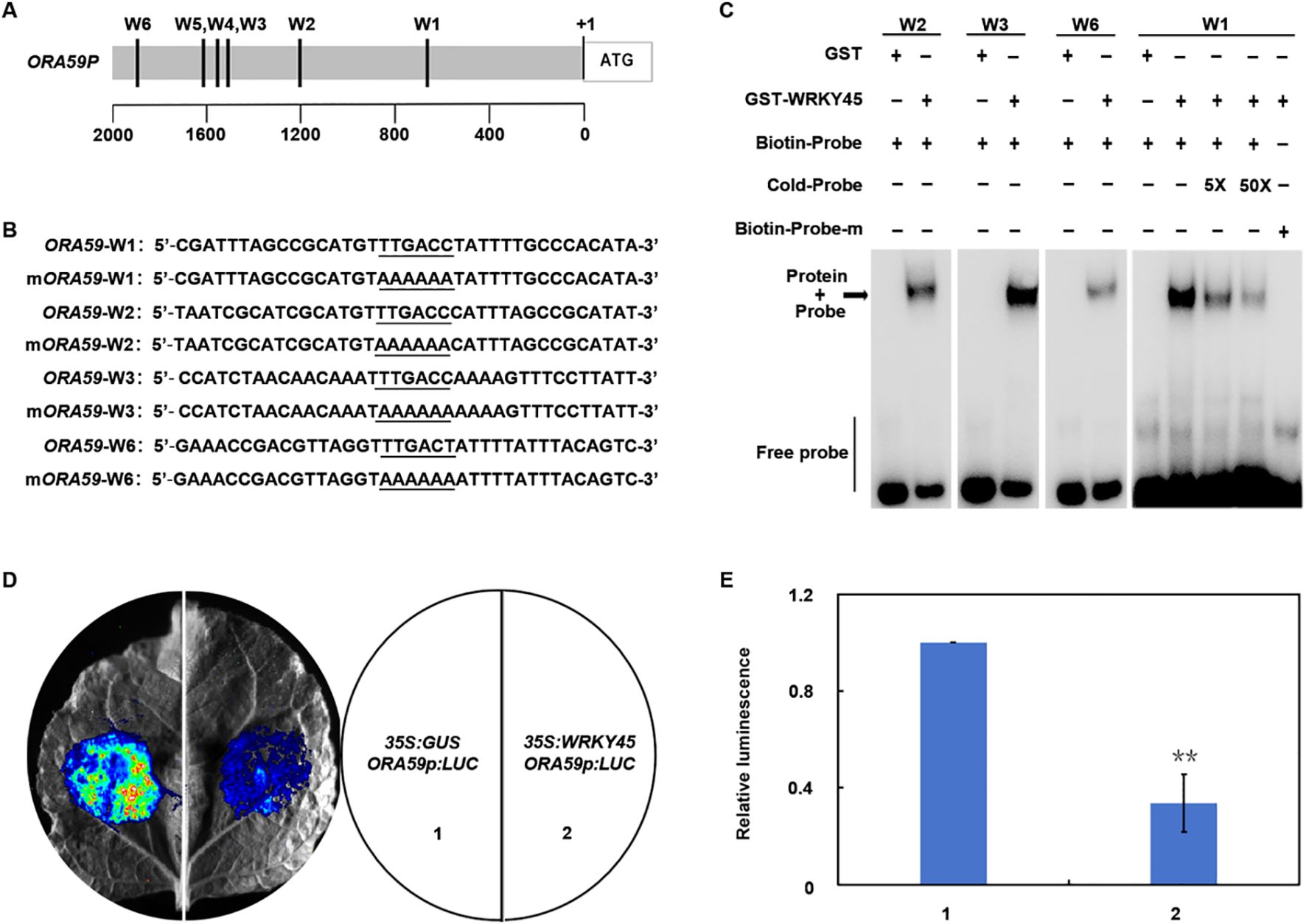

Figure 2. WRKY45 directly represses ORA59 and downstream JA/ET-responsive defense genes. (A) Schematic representation of the ORA59 promoter showing six putative W-box elements (W1–W6). (B) Nucleotide sequences of the W-box elements used in DNA-binding assays, with core motifs and mutated nucleotides underlined. (C) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) showing the interaction between GST–WRKY45 and W-box elements of the ORA59 promoter. GST protein alone was used as negative control. “5×” and “50×” denote addition of fivefold and fiftyfold excess of unlabeled competitor probe, respectively; “+” and “−” denote presence or absence of competitor probes. (D) Transient dual-luciferase assays in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Representative luminescence images of co-infiltration with (1) 35S:GUS + ORA59p:LUC (control) and (2) 35S:WRKY45 + ORA59p:LUC are shown. (E) Quantitative analysis of luciferase activity. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 independent biological replicates). Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed Student’s t-test, and asterisks indicate significant differences (**P < 0.01).

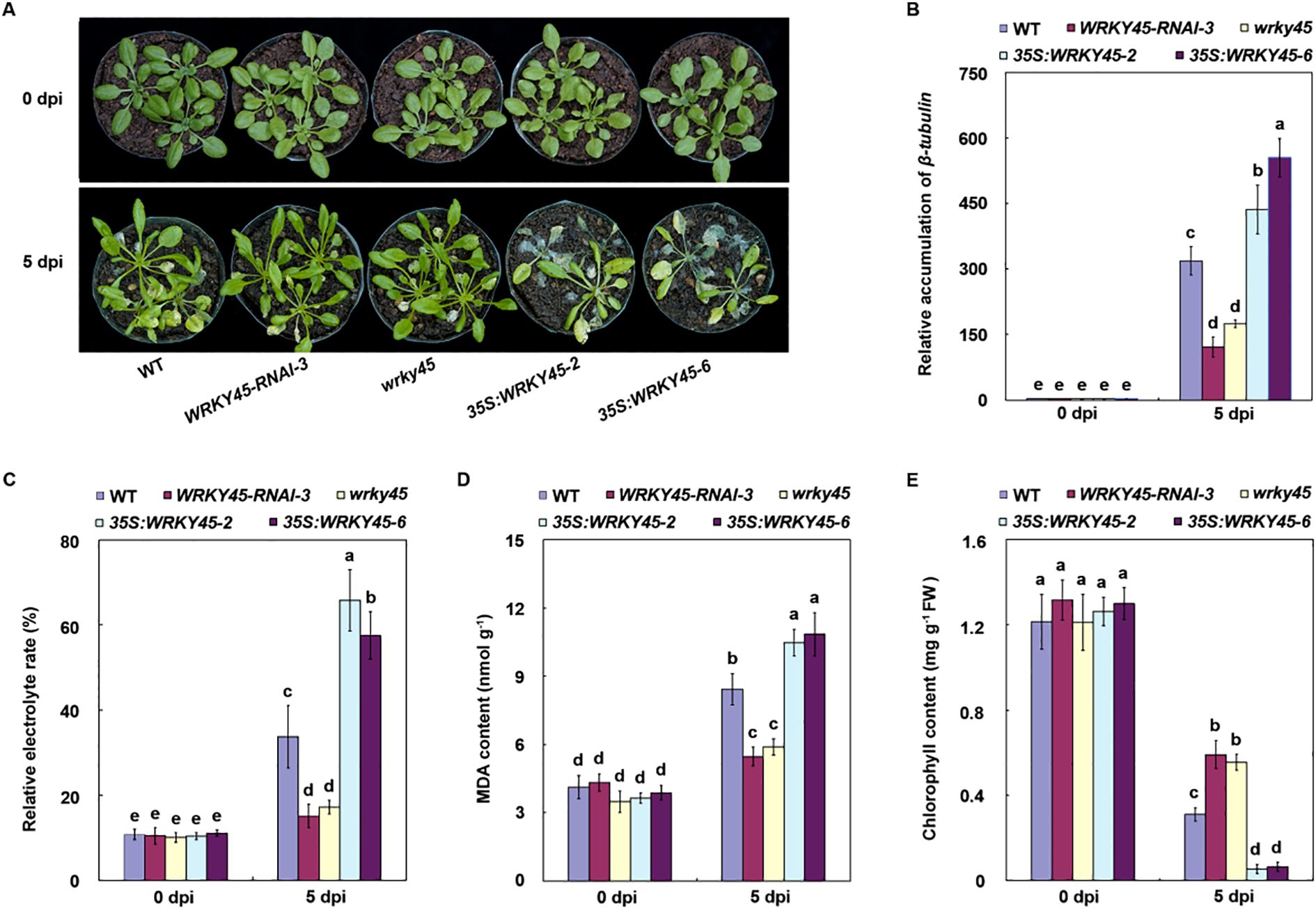

Figure 3. WRKY45 negatively regulates Arabidopsis resistance to B. cinerea. (A) Disease phenotypes of wild-type plants, wrky45 mutants, WRKY45−RNAi lines, and WRKY45 overexpression plants at 0 and 5 days post-inoculation (dpi) with B. cinerea. (B) Fungal biomass in infected leaves quantified by β−tubulin transcripts using qRT−PCR, with ACTIN2 as the internal reference gene for normalization. (C–E) Electrolyte leakage, malondialdehyde content, and chlorophyll content at 0 and 5 dpi. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 independent biological replicates). Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

3 Results

3.1 WRKY45 is transcriptionally activated by B. cinerea infection

To investigate the role of WRKY45 in resistance to B. cinerea, wild-type seedlings were inoculated with a suspension of B. cinerea spores, and WRKY45 transcript levels were assessed at various time points. qRT–PCR analysis revealed that WRKY45 expression was rapidly and significantly upregulated within 6 hours post-inoculation, with transcript levels progressively increasing and peaking at approximately 48 h (Figure 1A), indicating that WRKY45 expression is induced by B. cinerea. Subsequently, leaves of WRKY45p:GUS transgenic plants were inoculated with B. cinerea, and GUS staining was examined three days post-inoculation. A significantly stronger GUS signal was observed at the inoculation sites compared to the uninoculated regions (Figure 1B), further confirming the induction of WRKY45 expression by B. cinerea. Collectively, these results demonstrate that WRKY45 is a pathogen-inducible transcription factor, potentially modulating defense responses to B. cinerea.

3.2 WRKY45 is a negative regulator of Arabidopsis responses to B. cinerea

To investigate the role of WRKY45 in Arabidopsis resistance to B. cinerea, we assessed the disease responses of wild-type, wrky45 knockout mutants, WRKY45-RNAi lines, and WRKY45 overexpression plants following B. cinerea inoculation. All lines exhibited comparable growth under normal conditions, with no discernible phenotypic differences. At 5 days post-inoculation, wrky45 and RNAi plants exhibited significantly enhanced resistance compared with wild-type, whereas 35S:WRKY45 plants displayed pronounced susceptibility (Figure 3A). To quantify pathogen biomass, we examined the accumulation of B. cinerea β-tubulin transcripts at 0 and 5 dpi. At 0 dpi, β-tubulin levels were nearly undetectable across all genotypes. However, at 5 dpi, β-tubulin transcript abundance was markedly reduced in the wrky45 and RNAi lines but substantially increased in the WRKY45 overexpression plants (Figure 3B). These results consistently suggest that WRKY45 functions as a negative regulator of Arabidopsis resistance to B. cinerea.

To further evaluate the physiological consequences of WRKY45 activity, we measured membrane integrity, oxidative stress, and chlorophyll retention. The wrky45 and RNAi plants exhibited significantly lower electrolyte leakage and malondialdehyde levels compared with WT, indicating reduced cellular damage, whereas 35S:WRKY45 lines showed exacerbated membrane injury and oxidative stress (Figures 3C, D). Moreover, chlorophyll content was better preserved in wrky45 and RNAi plants but was strongly depleted in the WRKY45 overexpression lines, correlating with their increased disease severity (Figure 3E). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that WRKY45 functions as a negative regulator of Arabidopsis resistance to B. cinerea.

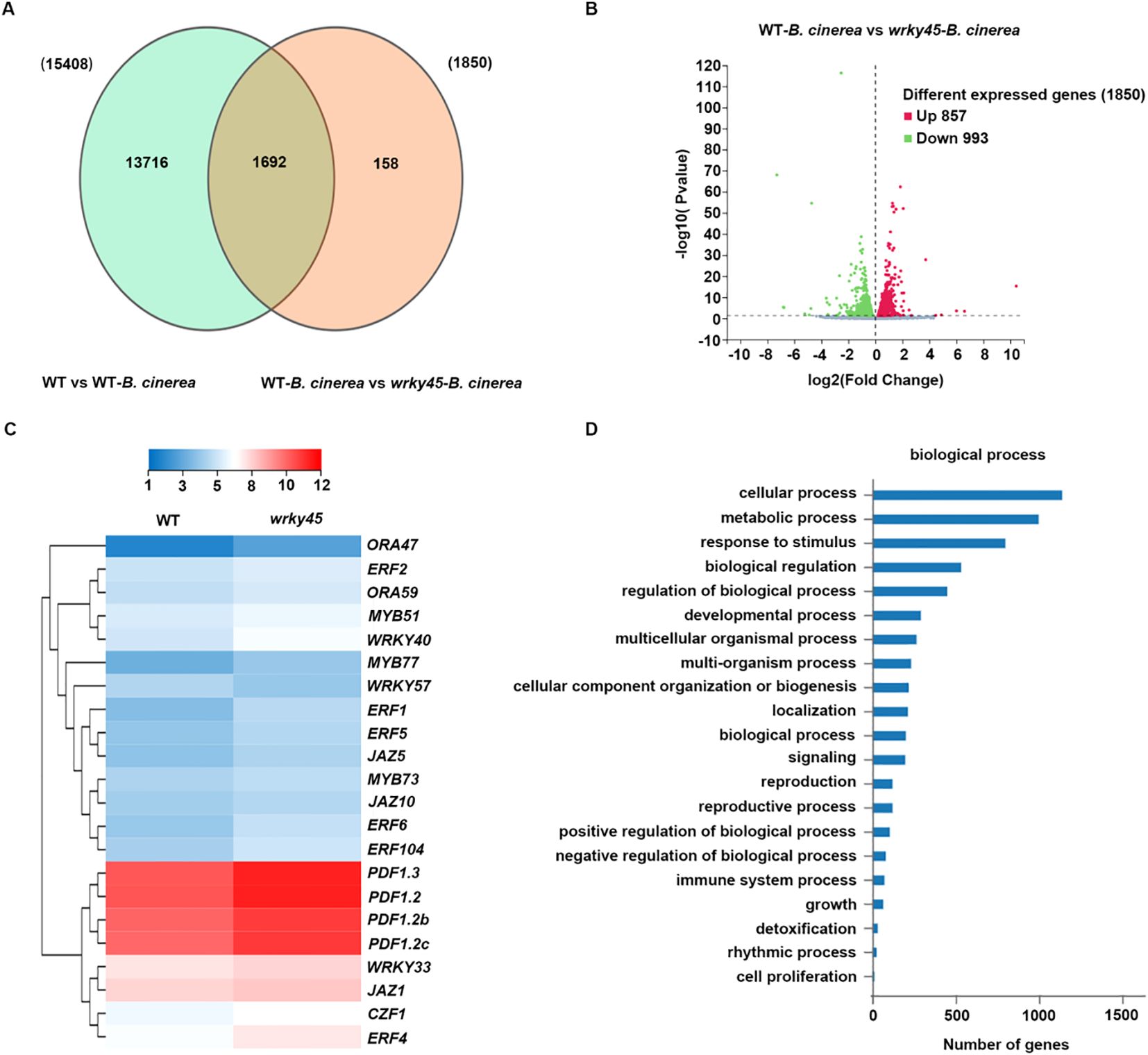

3.3 RNA-seq analysis to identify the potential WRKY45-involved pathway to control defense response

To elucidate the transcriptional basis of WRKY45-mediated defense, we performed RNA-seq analysis on wild-type and wrky45 plants, with samples collected before and after inoculation with B. cinerea. A Venn diagram analysis revealed 15,408 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in WT versus WT-B. cinerea, while 1,850 DEGs were identified in wrky45 versus WT under infection conditions, with 1,692 genes shared between the two comparisons (Figure 4A). Among the 1,850 DEGs detected in the wrky45 mutant, 857 were up-regulated and 993 were down-regulated (Figure 4B). Hierarchical clustering of representative defense-related genes showed that loss of WRKY45 significantly enhanced the expression of several JA/ET marker genes, including PDF1.2, PDF1.2b, PDF1.2c, and ORA59, as well as stress-associated transcription factors such as WRKY33, MYB77, and multiple ERF genes (e.g., ERF1, ERF4, ERF5, ERF6) (Figure 4C). Notably, these genes are well-established regulators of immunity against necrotrophic pathogens, indicating that WRKY45 negatively modulates JA/ET-mediated defense transcriptional networks. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis further revealed that DEGs between WT and wrky45 plants upon infection were predominantly enriched in biological processes associated with immunity, such as “response to stimulus,” “immune system process,” “detoxification,” and “regulation of biological process” (Figure 4D). Collectively, these results demonstrate that WRKY45 deficiency reprograms transcriptional responses toward enhanced activation of defense-related pathways, thereby strengthening resistance to B. cinerea.

Figure 4. Transcriptomic analysis reveals WRKY45-dependent regulation of defense-associated genes in response to B. cinerea. (A) Venn diagram showing the overlap of genes co-regulated by B. cinerea and WRKY45 deficiency. The overlapping region represents genes co-regulated in the comparisons WT vs. WT–B. cinerea and WT–B. cinerea vs. wrky45–B. cinerea. (B) Volcano plot displaying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between WT–B. cinerea vs. wrky45–B. cinerea. DEGs were defined using thresholds |log2 fold change| ≥ 1 and adjusted P value (Padj) < 0.05. The X-axis represents the fold change of the difference after conversion to log2, and the Y-axis represents the significance value after conversion to-log10. Red and green dots indicate up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs, respectively. (C) Hierarchical clustering of representative JA/ET-responsive, defense-related genes in the wrky45 mutant following (B) cinerea infection. (D) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of 1,850 DEGs in the wrky45 mutant after (B) cinerea treatment, highlighting significant enrichment in biological processes related to plant immunity.

3.4 WRKY45 represses the expression of JA/ET-dependent defense genes

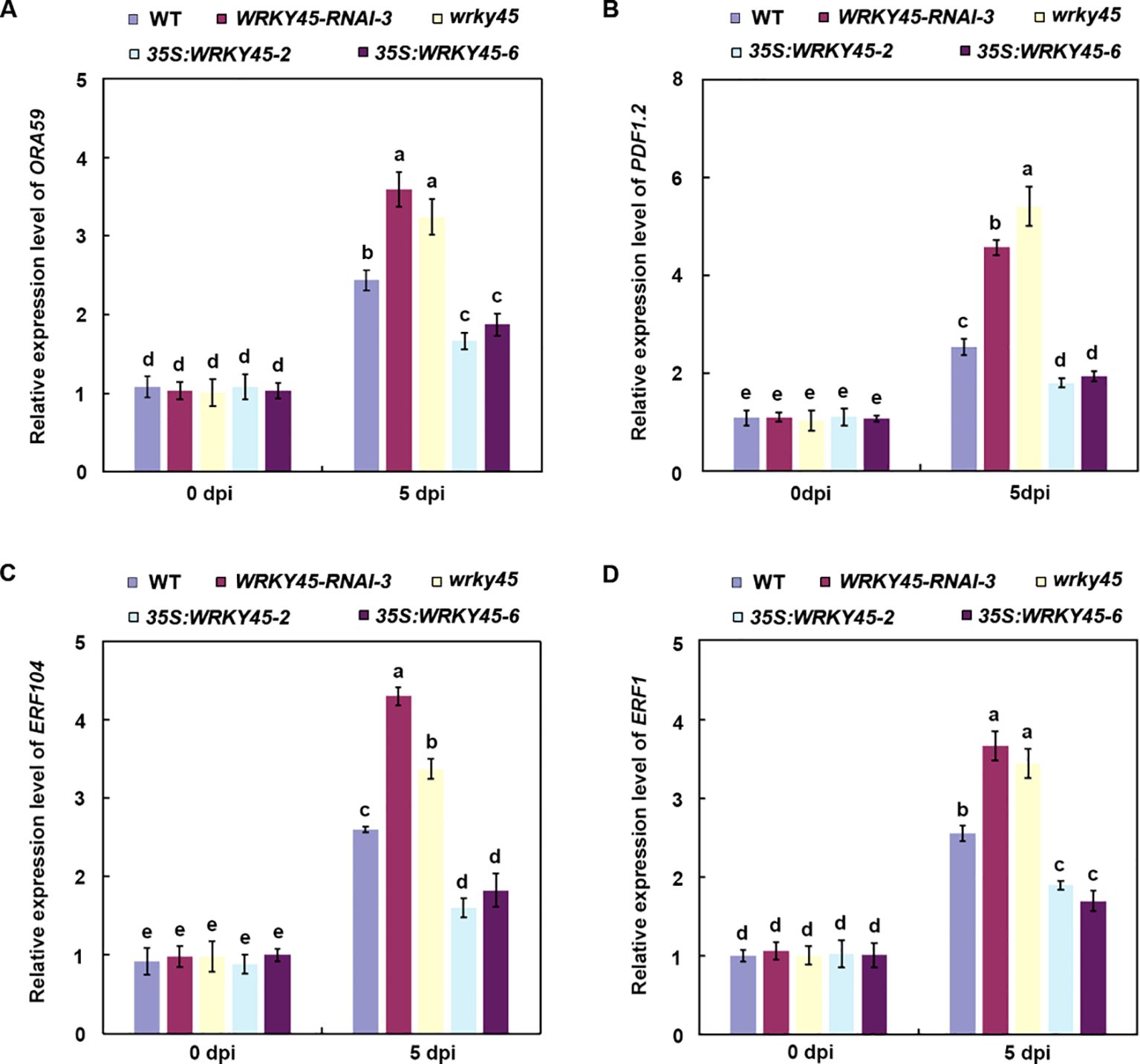

To validate the transcriptional regulation of defense genes revealed by the RNA-seq analysis, we examined the expression levels of multiple JA/ET-dependent genes in different plant lines following B. cinerea infection. qRT–PCR analysis showed that the expression levels of ORA59, PDF1.2, ERF104, and ERF1 in the wrky45 mutant and WRKY45-RNAi plants were not significantly different from those in the wild type at 0 dpi, but were markedly upregulated at 5 dpi relative to the wild type (Figures 5A–D). By contrast, their transcript levels were significantly repressed in WRKY45 overexpression lines, consistent with their enhanced susceptibility (Figures 5A–D). These findings, together with the RNA-seq results, demonstrate that WRKY45 functions as a negative regulator of JA/ET-mediated defense by repressing key downstream immune genes, thereby attenuating the host immune response against B. cinerea.

Figure 5. WRKY45 represses the expression of JA/ET-dependent defense genes. (A–D) Relative expression levels of ORA59 (A), PDF1.2 (B), ERF104 (C), and ERF1 (D) were quantified by qRT–PCR in wild-type, wrky45 knockout mutants, WRKY45-RNAi lines, and WRKY45 overexpression plants at 0 and 5 days post-inoculation (dpi) with B. cinerea. using ACTIN2 as the internal reference gene. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 independent biological replicates). Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

3.5 WRKY45 directly binds to the ORA59 promoter and represses its transcriptional activity

To investigate whether WRKY45 directly regulates ORA59, we analyzed the ORA59 promoter and identified several putative W-box elements (W1–W6) (Figures 2A, B). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays showed that recombinant GST–WRKY45 protein strongly bound to probes containing the W2, W3, and W6 elements, whereas while no binding signal was detected with the mutated W1 probe (Figure 2C). Competitive binding assays further demonstrated that an excess of unlabeled probes effectively blocked binding, confirming the specificity of these interactions (Figure 2C). To assess the functional relevance of this binding, transient dual-luciferase assays were performed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Co-expression of WRKY45 with the ORA59 promoter-driven LUC reporter significantly reduced luminescence compared to the control, indicating that WRKY45 suppresses ORA59 transcriptional activity (Figures 2D, E). Additionally, transient assays using the promoters of PDF1.2, ERF104, and ERF1 revealed that WRKY45 consistently repressed their transcriptional activity (Supplementary Figure 2). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that WRKY45 functions as a transcriptional repressor by directly binding to the ORA59 promoter and suppressing JA/ET-dependent immune genes, thereby attenuating Arabidopsis resistance to B. cinerea.

4 Discussion

Gray mold, caused by the fungal pathogen B. cinerea, poses a significant threat to a wide range of crop species. WRKY transcription factors are crucial regulators of plant growth, development, and stress adaptation. In Arabidopsis, the functional characterization of individual WRKY members under both biotic and abiotic stresses has been key to uncovering the transcriptional networks involved in plant immunity. Here, we provide mechanistic insights into how WRKY45 modulates resistance to B. cinerea using Arabidopsis as a model.

Our phenotypic and physiological analyses show that WRKY45 loss-of-function plants exhibit enhanced resistance to B. cinerea, while overexpression lines display increased susceptibility. These findings align with previous reports that several WRKY proteins act as immune repressors. For example, WRKY7, WRKY11, and WRKY17 suppress basal defense by downregulating JA and SA associated signaling (Fuenzalida-Valdivia et al., 2024). Notably, the phenotypes of WRKY45 mutants are similar to those of the wrky70 wrky54 double mutant, which exhibits enhanced resistance to necrotrophs, including B. cinerea, and shows strong induction of JA/ET- and SA-responsive genes (Li et al., 2017). These similarities support the conclusion that WRKY45 is part of a broader group of WRKY repressors that maintain immune homeostasis. However, unlike these previously described WRKY proteins, WRKY45 directly targets ORA59, a central integrator of JA/ET signaling, suggesting a more specialized role at a critical signaling node.

Transcriptomic profiling further revealed that WRKY45 deficiency leads to the strong activation of hallmark JA/ET-responsive genes, including ORA59, PDF1.2, ERF104, and ERF1. This transcriptional profile contrasts with that of wrky33 mutants, where WRKY33 primarily regulates camalexin biosynthesis and ROS homeostasis (Birkenbihl et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2015). In contrast, this pattern more closely resembles the WRKY57-mediated repression of B. cinerea resistance described by Jiang and Yu, which acts through the JA signaling pathway (Jiang and Yu, 2016). These distinctions underscore the functional diversification within the WRKY family, where distinct members either activate or repress defense pathways depending on physiological and environmental contexts.

Mechanistically, we show that WRKY45 directly binds multiple W-box motifs in the ORA59 promoter and suppresses its transcriptional activity. Since ORA59 integrates JA and ET signals, its repression by WRKY45 provides a highly efficient mechanism for modulating downstream immune activation. This direct suppression at the promoter level distinguishes WRKY45 from WRKY11 and WRKY17, which modulate defense indirectly through JA signaling cascades (Journot-Catalino et al., 2006). Moreover, WRKY45’s ability to repress the promoters of PDF1.2, ERF104, and ERF1 suggests that it may coordinate a broader transcriptional repression module that limits JA/ET-mediated immunity.

Despite these findings, several important questions remain. Whether WRKY45 is involved in the hormonal interplay between JA, SA, and ET is still unclear. Additionally, B. cinerea infection is characterized by dynamic shifts from biotrophic-like to necrotrophic growth (Reboledo et al., 2020). High-resolution temporal transcriptomics, chromatin accessibility profiling, or single-cell RNA-seq could provide further insights into how WRKY45 activity changes during these distinct infection phases.

In conclusion, our results establish WRKY45 as a transcriptional repressor that attenuates JA/ET-mediated defense against B. cinerea. By directly suppressing ORA59 and downstream immune genes, WRKY45 fine-tunes host defense responses. These findings enhance our understanding of WRKY-mediated transcriptional repression and open new avenues for translational research to enhance disease resistance in crops.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we identified WRKY45 as a transcriptional repressor that negatively regulates Arabidopsis defense against B. cinerea by suppressing JA/ET-mediated immune signaling. Loss of WRKY45 function enhanced resistance, reduced oxidative damage, and better preserved cellular integrity under pathogen challenge, whereas overexpression of WRKY45 increased susceptibility to B. cinerea. Mechanistically, WRKY45 directly binds to W-box motifs in the ORA59 promoter inhibits its transcriptional activation, thereby attenuating the expression of downstream defense genes such as PDF1.2, ERF104, and ERF1. These findings not only enhance our understanding of the complex transcriptional networks governing plant immunity but also highlight the dual, context-dependent roles of WRKY transcription factors in fine-tuning stress responses. Given its conserved regulatory motifs, WRKY45 may serve as a promising target for molecular breeding and genome editing strategies aimed at enhancing crop tolerance to necrotrophic fungal pathogens.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1390436.

Author contributions

HR: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Software, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Validation. ZY: Writing – review & editing, Software, Validation. ZC: Validation, Software, Writing – review & editing. YM: Writing – review & editing, Software. SB: Writing – review & editing, Software. YC: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Funding acquisition. MC: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. WG: Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32360077); the Tibet Autonomous Region Key Research and Development Project (XZ202201ZY0011N); the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (QKHJC-ZK[2024]YB660, QKHJC-ZK[2022]YB537, and QKHJC-ZK[2022]YB536); the Science and Technology Cooperation Project of Zunyi (HZ (2024) 382); and the Moutai Institute High-Level Talent Research Commencement Funding Project (mygccrc[2022]068, mygccrc[2022]063 and mygccrc[2022]061).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Chen Ligang for the generous provision of WRKY45 overexpression seeds. We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden and Moutai Institute for providing the experimental platform.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1724180/full#supplementary-material

References

AbuQamar, S., Moustafa, K., and Tran, L. S. (2017). Mechanisms and strategies of plant defense against Botrytis cinerea. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 37, 262–274. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2016.1271767

Bajji, M., Kinet, J. M., and Lutts, S. (2002). The use of the electrolyte leakage method for assessing cell membrane stability as a water stress tolerance test in durum wheat. Plant Growth Regul. 36, 61–70. doi: 10.1023/A:1014732714549

Barros, J. A. S., Cavalcanti, J. H. F., Pimentel, K. G., Medeiros, D. B., Silva, J. C. F., Condori-Apfata, J. A., et al. (2022). The significance of WRKY45 transcription factor in metabolic adjustments during dark-induced leaf senescence. Plant Cell Environ. 45, 2682–2695. doi: 10.1111/pce.14393

Bi, K., Scalschi, L., Jaiswal, N., Mengiste, T., Fried, R., Sanz, A. B., et al. (2021). The Botrytis cinerea Crh1 transglycosylase is a cytoplasmic effector triggering plant cell death and defense response. Nat. Commun. 12, 2166. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22436-1

Birkenbihl, R. P., Diezel, C., and Somssich, I. E. (2012). Arabidopsis WRKY33 is a key transcriptional regulator of hormonal and metabolic responses toward Botrytis cinerea infection. Plant Physiol. 159, 266–285. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.192641

Brunello, L., Kunkowska, A. B., Olmi, E., Triozzi, P. M., Castellana, S., Perata, P., et al. (2024). The transcription factor ORA59 represses hypoxia responses during Botrytis cinerea infection and reoxygenation. Plant Physiol. 197, kiae677. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiae677

Chen, L., Song, Y., Li, S., Zhang, L., Zou, C., and Yu, D. (2012). The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant abiotic stresses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Regul. Mech. 1819, 120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.09.002

Chen, L., Xiang, S., Chen, Y., Li, D., and Yu, D. (2017). Arabidopsis WRKY45 interacts with the DELLA protein RGL1 to positively regulate age-triggered leaf senescence. Mol. Plant 10, 1174–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.07.008

Chen, L., Zhang, L., Li, D., Wang, F., and Yu, D. (2013). WRKY8 transcription factor functions in the TMV-cg defense response by mediating both abscisic acid and ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E1963–E1971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221347110

Chen, L., Zhang, L., Xiang, S., Chen, Y., Zhang, H., and Yu, D. (2021). ). The transcription factor WRKY75 positively regulates jasmonate-mediated plant defense to necrotrophic fungal pathogens. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 1473–1489. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa529

Cheng, Q., Dong, L., Gao, T., Liu, T., Li, N., Wang, L., et al. (2018). The bHLH transcription factor GmPIB1 facilitates resistance to Phytophthora sojae in Glycine max. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 2527–2541. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery103

Chen, X., Zhang, T., Wang, H., Zhao, W., and Guo, Z. (2025). Transcription factor WRKY complexes in plant signaling pathways. Phytopathol. Res. 7, 1–21. doi: 10.1186/s42483-025-00349-x

Dean, R., Van Kan, J. A., Pretorius, Z. A., Hammond-Kosack, K. E., Di Pietro, A., Spanu, P. D., et al. (2012). The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 414–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00783.x

Du, P., Wang, Q., Yuan, D. Y., Chen, S. S., Su, Y. N., Li, L., et al. (2023). WRKY transcription factors and OBERON histone-binding proteins form complexes to balance plant growth and stress tolerance. EMBO J. 42, e113639. doi: 10.15252/embj.2023113639

Fuenzalida-Valdivia, I., Herrera-Vásquez, A., Gangas, M. V., Sáez-Vásquez, J., Álvarez, J. M., Meneses, C., et al. (2024). The Negative Regulators of the Basal Defence WRKY7, WRKY11 and WRKY17 modulate the jasmonic acid pathway and an alternative splicing regulatory network in response to Pseudomonas syringae in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 25, 70044. doi: 10.1111/mpp.70044

Glazebrook, J. (2005). Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43, 205–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135923

Huang, Z., He, J., Xia, D., Zhong, X. J., Li, X., Sun, L., et al. (2016). Evaluation of physiological responses and tolerance to low-temperature stress of four Iceland poppy (Papaver nudicaule) varieties. J. Plant Interact. 11, 117–123. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2016.1217433

Jiang, Y., Guo, L., Liu, R., Jiao, B., Zhao, X., Ling, Z., et al. (2016). Overexpression of poplar PtrWRKY89 in transgenic Arabidopsis leads to a reduction of disease resistance by regulating defense-related genes in salicylate- and jasmonate-dependent signaling. PloS One 11, e0149137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149137

Jiang, J., Ma, S., Ye, N., Jiang, M., Cao, J., and Zhang, J. (2017). WRKY transcription factors in plant responses to stresses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 59, 86–101. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12513

Jiang, Y. and Yu, D. (2016). The WRKY57 transcription factor affects the expression of jasmonate ZIM-domain genes transcriptionally to compromise Botrytis cinerea resistance. Plant Physiol. 171, 2771–2782. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00747

Journot-Catalino, N., Somssich, I. E., Roby, D., and Kroj, T. (2006). The transcription factors WRKY11 and WRKY17 act as negative regulators of basal resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 18, 3289–3302. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044149

Ju, S., Go, Y. S., Choi, H. J., Park, J. M., and Suh, M. C. (2017). DEWAX transcription factor is involved in resistance to Botrytis cinerea in Arabidopsis thaliana and Camelina sativa. Front. Plant Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01210

Kang, M., Wu, H., Liu, H., Liu, W., Zhu, M., Han, Y., et al. (2023). The pan-genome and local adaptation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Commun. 14, 6259. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42029-4

Li, F., Deng, Y., Liu, Y., Mai, C., Xu, Y., Wu, J., et al. (2023). Arabidopsis transcription factor WRKY45 confers cadmium tolerance via activating PCS1 and PCS2 expression. J. Hazard Mat 460, 132496. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.132496

Li, J., Zhong, R., and Palva, E. T. (2017). WRKY70 and its homolog WRKY54 negatively modulate the cell wall-associated defenses to necrotrophic pathogens in Arabidopsis. PloS One 12, e0183731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183731

Lichtenthaler, H. K. (1987). Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes[M]//Methods in enzymology. Acad. Press 148, 350–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)48036-1

Liu, S., Kracher, B., Ziegler, J., Birkenbihl, R. P., and Somssich, I. E. (2015). Negative regulation of ABA signaling by WRKY33 is critical for Arabidopsis immunity towards Botrytis cinerea. eLife 4, e07295. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07295

Liu, Q., Li, X., Yan, S., Yu, T., Yang, J., Dong, J., et al. (2018). OsWRKY67 positively regulates blast and bacterial blight resistance by direct activation of PR genes in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 18, 257. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1479-y

Lorenzo, O., Piqueras, R., Sánchez-Serrano, J. J., and Solano, R. (2003). ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 integrates signals from ethylene and jasmonate pathways in plant defense. Plant Cell 15, 165–178. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007468

Luo, D., Cai, J., Sun, W., Yang, Q., Hu, G., and Wang, T. (2024). Tomato SlWRKY3 negatively regulates Botrytis cinerea resistance via TPK1b. Plants 13, 1597. doi: 10.3390/plants13121597

Penninckx, I. A., Eggermont, K., Terras, F. R., Thomma, B. P., De Samblanx, G. W., Buchala, A., et al. (1996). Pathogen-induced systemic activation of a plant defensin gene in Arabidopsis follows a salicylic acid-independent pathway. Plant Cell 8, 2309–2323. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.12.2309

Pré, M., Atallah, M., Champion, A., De Vos, M., Pieterse, C. M., and Memelink, J. (2008). The AP2/ERF domain transcription factor ORA59 integrates jasmonic acid and ethylene signals in plant defense. Plant Physiol. 147, 1347–1357. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.117523

Rasool, K. G., Khan, M. A., Aldawood, A. S., Tufail, M., Mukhtar, M., and Takeda, M. (2015). Identification of proteins modulated in the date palm stem infested with red palm weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Oliv.) using two-dimensional differential gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 19326–19346. doi: 10.3390/ijms160819326

Reboledo, G., Agorio, A., Vignale, L., Batista-García, R. A., and Ponce De, León, I. (2020). Botrytis cinerea transcriptome during the infection process of the bryophyte Physcomitrium patens and angiosperms. J. Fungi 7, 11. doi: 10.3390/jof7010011

Scholz, P., Chapman, K. D., Ischebeck, T., and Guzha, A. (2023). Quantification of Botrytis cinerea Growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Bio-protocol 13, e4740. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.4740

Song, H., Li, Y., Wang, Z., Duan, Z., Wang, Y., Yang, E., et al. (2022). Transcriptome profiling of Toona ciliata young stems in response to Hypsipyla robusta Moore. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.950945

van Kan, J. A. (2006). Licensed to kill: the lifestyle of a necrotrophic plant pathogen. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.03.005

Vatov, E., Ludewig, U., and Zentgraf, U. (2021). Disparate dynamics of gene body and cis-regulatory element evolution illustrated for the senescence-associated cysteine protease gene SAG12 of plants. Plants 10, 1380. doi: 10.3390/plants10071380

Wang, W., Cao, H., Wang, J., and Zhang, H. (2025). Recent advances in functional assays of WRKY transcription factors in plant immunity against pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1517595

Wang, X., Guo, R., Tu, M., Wang, D., Guo, C., Wan, R., et al. (2017). Ectopic expression of the wild grape WRKY transcription factor VqWRKY52 in Arabidopsis enhances resistance to the biotrophic pathogen powdery mildew but not to the necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea. Front. Plant Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00097

Wang, H., Xu, Q., Kong, Y. H., Chen, Y., Duan, J. Y., Wu, W. H., et al. (2014). Arabidopsis WRKY45 transcription factor activates PHOSPHATE TRANSPORTER1;1 expression in response to phosphate starvation. Plant Physiol. 164, 2020–2029. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.235077

Xiang, S., Wu, S., Zhang, H., Mou, M., Chen, Y., Li, D., et al. (2020). The PIFs redundantly control plant defense response against Botrytis cinerea in Arabidopsis. Plants 9, 1246. doi: 10.3390/plants9091246

Zhang, H., Zhang, L., Ji, Y., Jing, Y., Li, L., Chen, Y., et al. (2022). Arabidopsis SIGMA FACTOR BINDING PROTEIN1 (SIB1) and SIB2 inhibit WRKY75 function in abscisic acid-mediated leaf senescence and seed germination. J. Exp. Bot. 73, 182–196. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erab391

Zhou, X., Sun, Z., Huang, Y., He, D., Lu, L., Wei, M., et al. (2025). WRKY45 positively regulates salinity and osmotic stress responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 219, 109408. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.109408

Keywords: Arabidopsis, Botrytis cinerea, defense response, molecular mechanism, WRKY45

Citation: Ran H, Yuan Z, Chen Z, Mao Y, Bao S, Chen Y, Chen M, Zhang H and Gong W (2025) WRKY45 is a negative regulator of Botrytis cinerea resistance through the JA/ET signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1724180. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1724180

Received: 13 October 2025; Accepted: 01 December 2025; Revised: 27 November 2025;

Published: 19 December 2025.

Edited by:

Libei Li, Zhejiang Agriculture and Forestry University, ChinaReviewed by:

Long Chen, China National Rice Research Institute (CAAS), ChinaHao Zhang, Hebei Normal University, China

Copyright © 2025 Ran, Yuan, Chen, Mao, Bao, Chen, Chen, Zhang and Gong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haiyan Zhang, emh5Y2hlZXJAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Wenfeng Gong, emt4eWd3ZkB4emEuZWR1LmNu

Huifang Ran1

Huifang Ran1 Yuyu Chen

Yuyu Chen Haiyan Zhang

Haiyan Zhang