- 1State Key Laboratory of North China Crop Improvement and Regulation, Key Laboratory for Crop Germplasm Resources of Hebei, Hebei Agricultural University, Baoding, China

- 2North China Key Laboratory for Crop Germplasm Resources of Education Ministry, College of Agronomy, Hebei Agricultural University, Baoding, China

- 3Peanut Institute, Jilin Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Northeast Agricultural Research Center of China), Changchun, China

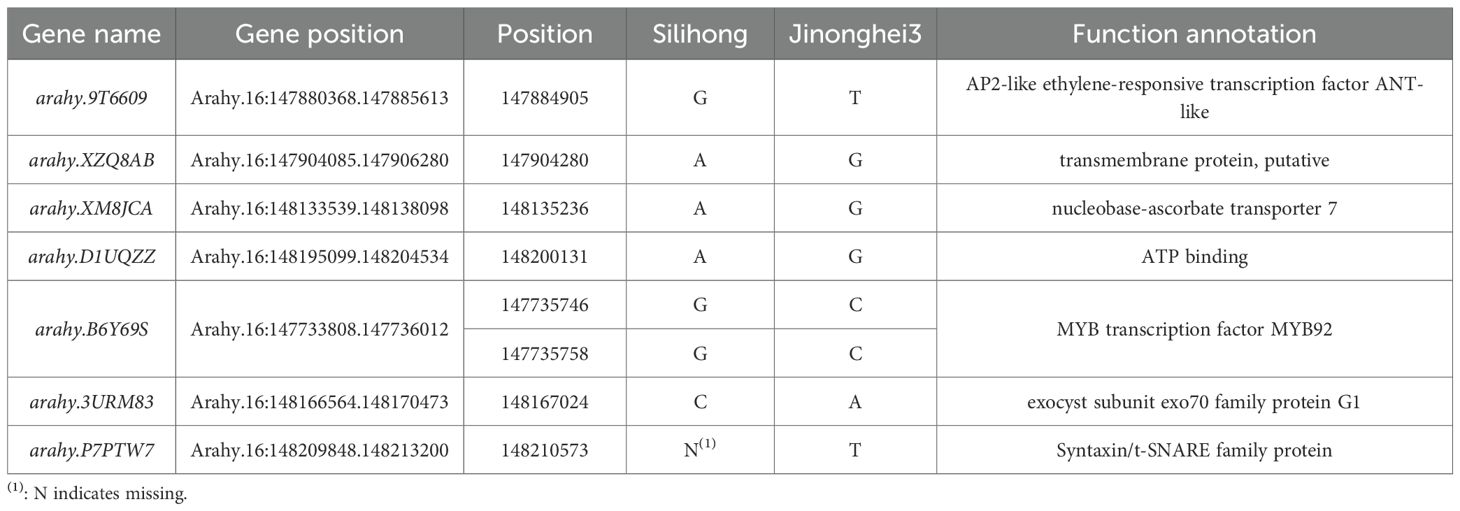

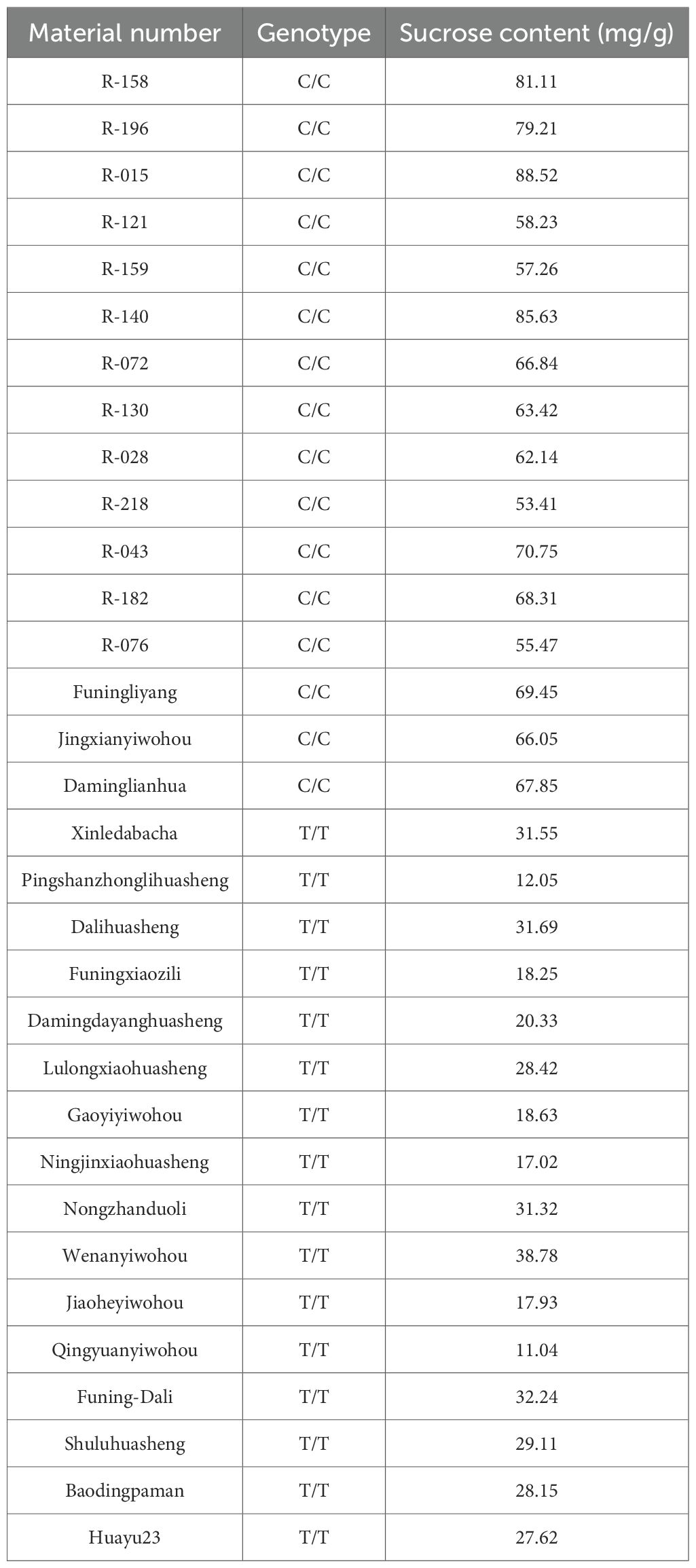

The total sugar content (TSC), soluble sugar content (SSC), and sucrose content (SC) are key determinants of taste and flavor of fresh and dried peanut kernels, and are important quality indicators in peanut breeding. However, the quantitative trait locus (QTLs) regulating peanut sugar content, especially in fresh seeds, remain poorly understood. In this study, TSC, SSC, and SC were measured in dried mature seeds (DMS) across four environments (three-year data from Baoding and Fuxin) and in fresh seeds (FS) across two environments (Baoding and Fuxin), and QTL mapping was performed in a recombinant inbred line (RIL) population (‘Silihong’×’Jinonghei3’). TSC, SSC, and SC were all lower in FS compared to DMS, indicating that the sugar content increased during the drying and maturation process. Two major co-localized QTLs, qA06 (physical location 115.08-115.73 Mb) and qB06 (physical location 147.74-148.46 Mb), were identified in multiple environments. qA06 was associated with TSC, SSC, and SC in DMS, and SSC in FS, spanning a 0.65 Mb physical interval. qB06, spanning a 0.72Mb physical interval, was associated with TSC, SSC, SC in DMS, and TSC, SSC in FS. qB06 represents a newly identified QTL in this study; within 56 candidate genes and 319 SNPs were screened. Among them, the genes arahy.3URM83 and arahy.41Y8R9, and arahy.P7PTW7 were closely related to sugar synthesis. Transcriptome analysis during the drying and maturation stages revealed that arahy.3URM83 and arahy.41Y8R9 were strongly associated with sugar content. The QTL regions identified in this study not only elucidate the genetic regulatory mechanism of peanut sugar content under different drying conditions but also enable the development of KASP markers, offering valuable resources for peanut quality improvement and targeted breeding programs.

1 Introduction

The total global peanut production exceeds 40 million tons, with 55% used for oil extraction and 35% - 45% used for various forms of consumption and food processing. More than half of the peanuts used for consumption are roasted, and this proportion continues to increase each year (Wang et al., 2025). The taste of fresh and roasted peanuts is primarily determined by sugars and volatile organic compounds. In addition, the sugar content of peanuts is closely related to their stability during storage. An optimal sugar content helps maintain the vitality of peanut seeds and reduces mold risk associated with abnormal sugar metabolism (Wang et al., 2018). Therefore, understanding the genetic and physiological mechanisms underlying sugar accumulation in peanuts is of great significance for specialized peanut storage and production.

Fresh peanuts refer to peanut seeds that are harvested and used directly for cooking without drying. Significant differences exist between fresh peanuts and dried peanuts in both sugar composition and concentration. Fresh peanut seeds have a high moisture content, and sugars comprise predominantly monosaccharides such as glucose and fructose, as well as oligosaccharides such as sucrose. After drying, the physiological metabolism of peanut seeds slows down due to water loss, and the consumption of sugars by respiration decreases. In addition, physical and chemical processes such as the Maillard reaction may occur during the drying process, affecting sugar transformation and concentration. Compared with fresh seeds, the sugar content and polysaccharide proportion of dried peanuts are significantly increased, resulting in a sweeter taste (Pattee et al., 2000). There are genetic differences underlying variation in sugar content between fresh and dried peanut kernels (Deng et al., 2025), suggesting distinct regulatory mechanisms. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct in-depth research in order to generate and cultivate specialized peanut varieties and guide peanut production.

Peanut sugar content is primarily governed by genetic factors but is also significantly influenced by the environment. Adequate and suitable light can promote the efficient synthesis of photosynthetic products in peanut leaves and their transport to seeds, thereby increasing sugar content (Wu et al., 2025). In terms of temperature, during the swelling period of peanut pods, significant diurnal temperature variations promote the accumulation and conversion of sugars. Soil fertility is equally important. A soil rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and other nutrients in a balanced proportion can provide sufficient nutrients for peanut growth, can facilitate efficient sugar biosynthesis pathways, thereby enhancing peanut sugar content (Zhou et al., 2007). Comprehensive evaluation of sugar content in genetically diverse peanut populations under varying light regimes can enable a more integrated understanding of the genetic and environmental factors regulating sugar metabolism and accumulation, and provide a theoretical basis for the production of high (low) sugar peanuts.

Sugar content in peanuts is a complex quantitative trait, controlled by multiple genes. QTL mapping is a valuable approach for understanding the genetic regulation mechanism of plant sugar content. Park et al. (2013) constructed a recombinant inbred line population and successfully identified multiple QTL loci related to sugar content, such as sucrose and glucose, in corn grains using high-density genetic mapping. Li et al. (2025) combined analyses of parental and natural populations to identify multiple QTLs related to ear sugar content in maize. Recently, the study of sucrose content regulation in peanut kernel has attracted the attention of many researchers. Current studies predominantly concentrate on the genetic mechanisms underlying sucrose accumulation in dried peanuts, with several QTLs for sucrose content in dried peanuts having been identified (Li et al., 2023; Guo J. et al., 2023; Guo J. B, et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024, 2024). However, QTLs for TSC and SSC in dried peanuts, and sugar content in fresh peanuts remain largely uncharacterized. A systematic investigation of the sugar content and type in fresh and dried peanuts across different environments is essential for elucidating the roles of QTLs, the metabolic processes involved, and the interactions between genes and the environment.

In order to gain a deeper understanding of the genetic regulation mechanism of peanut sugar content, this study employed a RIL population exhibiting a normal distribution of sugar content-related traits, such as total sugar, soluble sugar, and sucrose. Through high-throughput sequencing and phenotypic assessment across different growth environments and developmental stages (fresh and dried seeds), QTL mapping was performed to identify loci associated with sugar accumulation. In order to clarify the key genes and genetic effects that control sugar content, expression analysis and KASP marker development were conducted on candidate genes to systematically carry out genetic analysis of peanut sugar content. These integrative analyses enhance our understanding of the genetic regulatory network of peanut sugar content, but also provide important theoretical basis and technical support for peanut quality breeding, supporting the sustainable development of the peanut industry.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant materials

The RIL population, comprising 248 individual lines derived from Silihong (A. hypogaea var. fastigiate) ×Jinonghei3 (A. hypogaea var. hypogaea), was used for QTL mapping. The population was developed at the experimental station of Hebei Agriculture University, Baoding, China. The RIL population and its parental lines were planted in experimental fields in Baoding (38.79°N, 115.56°E), Hebei Province (planted in May and harvested in September of 2018 (E1), 2020 (E2), and 2021 (E3)) and Fuxin (N42°01′, E121°40′), Liaoning Province (planted in May and harvested in September of 2021 (E4)). The parental lines and their 248 RILs were grown as previously described (Li et al., 2024). The browning of the inner fruit shell color signals the optimal timing for peanut harvest (Liang et al., 2018). At physiological maturity, seeds (E1 and E2) from eight middle-row plants in each plot were harvested and air-dried. 50% of the seeds harvested from E3 and E4 were stored at -20°C for FS sugar content analysis, and 50% were naturally air dried for DMS sugar content analysis. Store for future use once moisture content drops below 8% (Qu et al., 2022).

2.2 Determination of sugar content in peanut seeds

The total sugar content was determined using the 3, 5-dinitrosalicylic acid method according to Hou et al. (2017). Soluble sugar content was determined by the anthrone colorimetric method, as improved by Chen et al. (2022). A 0.1 g tissue sample was extracted from the middle section of the peanut cotyledon and homogenized using a tissue grinder (JXFSTPRP-24 A, Shanghai Jing Xin Co., LTD.). Subsequent procedures were performed in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions of the sugar content assay kit (Gris Biotechnology Co., LTD.).

2.3 Data analysis and heritability estimation

Statistical analyses, including analysis of variance (ANOVA), frequency distribution, and the independent sample t-test analysis, were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 software (IBM SPSS, USA).

2.4 QTL analysis

A high-density genetic map previously constructed in our laboratory was used for QTL mapping (Li et al., 2024). The inclusive composite interval mapping (ICIM) method in QTL IciMapping V4.2 software was used for scanning the phenotypic value and sugar content data in every environment. To validate the authenticity of detected QTLs and obtain more information, LOD≥2.5 and 1000 permutation test (PT) were employed as threshold methods. The PT method was used for detecting additive QTL. For individual environment analyses, as well as multi-environment joint and epistatic analyses, the BIP and MET functional modules of QTL IciMapping v4.2 were applied. QTLs were named as q + the abbreviated trait name + linkage group number, designating one of multiple QTL in a single linkage group following the international Rules of Genetic Nomenclature (Li et al., 2024).

2.5 Expression of candidate genes during the drying process

Candidate gene expression profiles related to sugar content were generated from transcriptome data (Deng et al., 2025). Transcriptome sequencing were used to analyze the regulatory mechanism during the drying process at five time points in parents. The transcriptome data of Silihong deposited in the NCBI SRA database (accession: PRJNA1212227). The transcriptome data of Jinonghei3 was unpublished.

2.6 KASP maker development and validation

The SNPS in the QTL interval of Silihong and Jinonghei3 were resequenced to develop KASP markers and subsequently screened. The primers were designed based on the differential SNP sequences identified. The primer sequences of KASPs are presented in Table 1. KASP assays were performed in 10 μL reaction volumes comprising 2.0 μL of genomic DNA (25–50 ng), 5 μL of 2×AQP master mix, 0.15 μmol L-1 of each forward primer, 0.4 μmol L-1 of the common reverse primer, and double-distilled water (JasonGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). PCR was performed on an ABI QuantStudio6 machine (ABI Life Technologies, CA, USA) using the following PCR conditions: 95°C for 10 min; 95°C for 20 s, 61°C (−0.6°C per cycle) for 40 s for 10 cycles; 95°C for 20 s, 55°C for 40 s for 31 cycles. Fluorescence was detected, and data analysis was manually performed using the built-in ABI QuantStudio6 software. Then, the KASP markers were assessed in a peanut panel comprising 13 lines and 19 peanut varieties and landraces cultivated in China.

3 Results

3.1 Analysis of sugar content in peanut kernel

In both fresh seeds (FS) and dried mature seeds (DMS), the TSC of Jinonghei3 was higher than that of Silihong, and the SSC and SC contents of Silihong exceeded those of Jinonghei3. However, across conditions, TSC, SSC, and SC of lines in DMS were higher than in FS (Figure 1). This indicates that the drying process affects the sugar content and that there are genetic differences.

Figure 1. Phenotypic distribution of sugar content traits for the RIL population. The x-axis shows the range of sugar content traits, including total sugar, soluble sugar, and sucrose in six environments. The y-axis shows the number of individuals of the RIL population. P1 and P2 represent the parents ‘Silihong’ and ‘Jinonghei3’, respectively.

The sugar contents of FS and DMS were affected by the environment. The TSC of DMS in E1 was lower than in other environments. The coefficients of variation for SC in DMS and FS were higher than those of TSC and SSC in the corresponding environment (Table 2), and transgressive segregation for SC was more pronounced in the offspring population.

TSC, SSC, and SC were all affected by both environmental and genetic factors. Heritability estimates indicated that genetic control predominated. TSC, SSC, and SC exhibited relatively high broad-sense heritability (h2), ranging from 0.66 to 0.89 (Table 3). Through genetic analysis of multi-environmental populations, the loci associated with phenotypic variation could be analyzed, and then the genetic mechanism of TSC, SSC, and SC in peanut was studied.

3.2 Analysis of QTLs associated with sugar content in peanut kernels

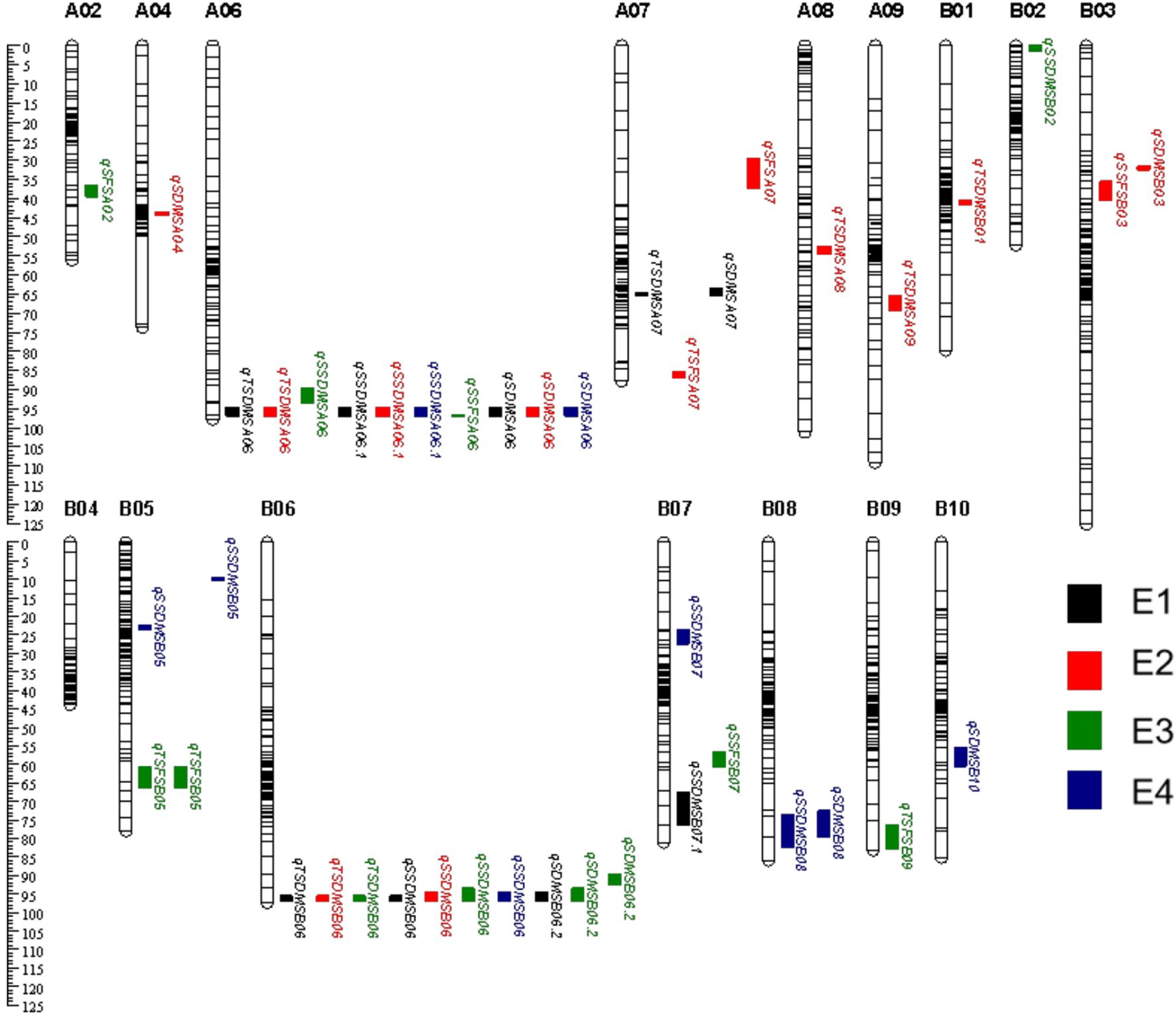

3.2.1 QTLs associated with the sugar content of DMS

A total of 22 QTLs associated with sugar content were detected in DMS. 6 QTLs associated with TSC-DMS with PVE of 2.75%-18.03% were mapped on 6 chromosomes, namely A06, A07, A08, A09, B01, and B06 (Figure 2). qTSDMSA06 and qTSDMSB06 were stably expressed across several environments with PVE between 7.69%-18.03%. The other 4 QTLs were only detected in a single environment (Table 4).

Figure 2. Distribution of QTL related to sugar content in four environments was identified by using composite interval mapping (CIM).

Eight QTLs were identified for SSC-DMS with 3.66%-19.87% PVE. These were distributed on A06, B02, B05, B06, B07 and B08 (Table 4). qSSDMSA06.1, detected in E1, E2, and E4 explained 9.29%-19.87% of the phenotypic variance. qSSDMSB06 detected in E1, E2, E3, and E4 explained 11.62%-16.97% of the variance (Table 4).

9 QTLs associated with SC-DMS with 3.31%-19.46% PVE. were mapped on 8 chromosomes including A04, A06, A07, B03, B05, B06, B08 and B10 (Figure 2). qSDMSA06, detected in E1, E2, and E4, explained 5.85%-15.52%. of the variance. qSDMSB06.2, detected in E1, E3, and E4 environments, explained 10.33%-19.46% of the variance. qSDMSB05, detected in E4, explained 13.98% of the variance. Donor alleles for qSDMSB05 were from the male parent ‘Jinonghei3’ (Table 4).

Two major chromosomal regions were consistently associated with sugar content. qTSDMSA06, qSSDMSA06.1, and qSDMSA06 were co-localized to the same interval (115.08Mb-115.73 Mb), between the flanking markers 1066 - 1067. qTSDMSB06, qSSDMSB06, and qSDMSB06.2 were co-localized to the 147.74Mb-148.46Mb region, between flanking markers 3330-3331 (Table 4). Additive effects (ranging between 3.70 and 24.69) indicated that the high-sugar content allele for qA06 was derived from the female parent ‘Silihong’. The additive effect of qB06 was between -31.58 and -0.72, implying the high-sugar content allele was derived from the male parent ‘Jinonghei3’. Moreover, these QTLs were detected in several environments with PVE values ranging from 7.22 to 19.46 (Table 4).

3.2.2 QTLs associated with sugar content in FS

A total of 11 QTLs associated with sugar content in FS across two environments were located on chromosomes A02, A05, A06, A07, A09, B03, B06, and B07, explaining 5.55-11.67% of the variance. 4 QTLs associated with TSC-FS were detected in four chromosomes, explaining 5.55-8.93% of the variance (Table 4). Among these, the state major QTL (qTSFSB06) explained 8.93% of the variation and co-localized with the major QTL region identified for TSC-DMS (Figure 2). For SSC-FS, 5 QTLs were detected in four chromosomes, explaining 4.99-10.15% of the variation. Stable major QTLs (qSSFSA06, qSSFSB06) explained 6.83-10.15% of the PVE and overlapped with the stable QTL region detected for SSC-DMS. For SC-FS, 2 QTLs were detected in chromosomes A02 and A07, explaining 7.14%–11.67% of the variation. These two SC-FS loci appeared to be FS-specific loci, and donor alleles conferring higher sugar content were contributed by’Jinonghei3’ (Table 4).

3.3 Candidate gene mining in the major QTL region on chromosome B06

A co-localized region between markers 3330–3331 on chromosome B06 with PVE values of 7.72% -19.46% was associated with TSC, SSC, and SC in DMS, as well as TSC and SSC in FS. The co-localized region was designated qSB06. To further investigate the genetic basis of sugar content in peanut seeds, genes within the qSB06 interval were examined. The genome of Tifrunner used as the reference genome (Bhat et al., 2023). qSB06 spanned approximately 722.71kb interval and contained 56 genes (Figure 3A). Resequencing of the two parental lines revealed 319 SNPs within this region, including nine within coding sequences. Among these, 1 SNP resulted in a synonymous mutation, 5 SNPs were missense mutations, and 1 SNP was missing (Table 5). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis indicated that most genes were related to cellular components (Figure 3B), with 5 genes involved in ATP binding. Among them, arahy.B6Y69S encodes the MYB transcription factor MYB92; Arahy.XM8JCA encodes an ascorbic acid transporter protein involved in transmembrane transport. Arahy.3URM83 and arahy.P7PTW7 encode exo70 family proteins G1 and Syntaxin/t-SNARE family proteins, respectively, involved in vesicle transport.

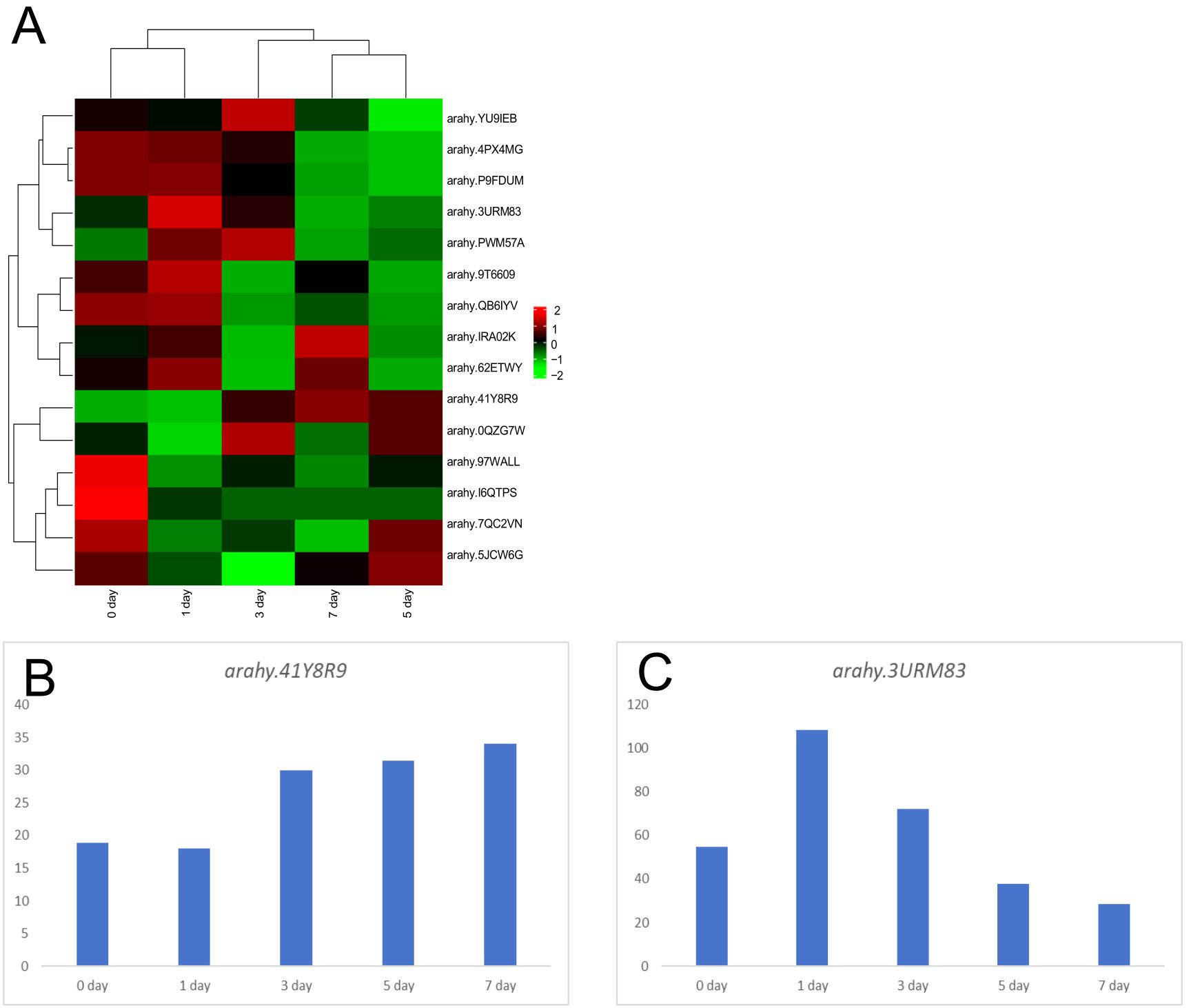

3.4 Expression analysis of candidate genes within the qSB06 interval during seed drying and maturation

The candidate genes within the qSB06 interval, defined as arahy.3URM83, arahy. 41Y8R9, and arahy.P7PTW7, were tightly associated with sugar synthesis. Arahy.3URM83, which encodes an exo70 family proteins of the extracellular vesicle subunit, exhibited an expression pattern that increased initially and then declined during the drying and maturation stages in both parental lines (Figure 4). Arahy.41Y8R9, encoding growth regulatory factor, showed the opposite expression trend compared to arahy.3URM83 during maturation, decreasing initially and subsequently increasing (Figure 4). Therefore, it can be inferred that this gene is also involved in sugar biosynthesis in peanuts and positively regulates sugar synthesis and accumulation. arahy. P7PTW7 is a Syntaxin/t-SNARE family protein involved in vesicle-mediated transport; however, in the transcriptome analysis, it showed no significant changes between the two parents (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Transcriptome analysis of candidate genes in the qB06 interval (A) Expression profiles of candidate sugar-related genes across five Silihong drying stages; (B) Expression levels of arahy.41Y8R9 in 5 periods; (C) Expression levels of arahy.3URM83 in 5 periods.

3.5 QTL validation using KASP markers

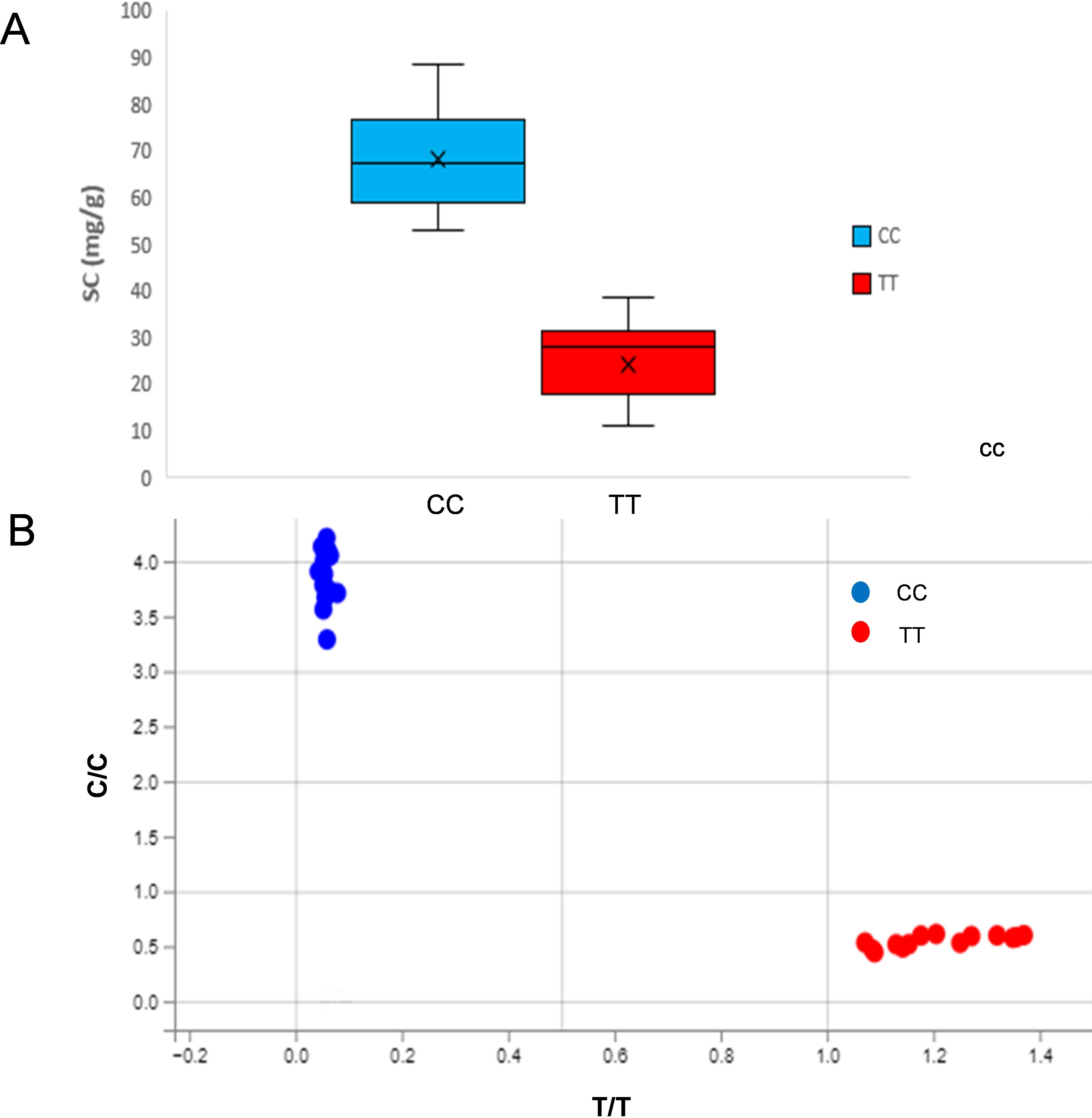

KASP markers developed based on the arahy.PKWB63 within the qB06 interval (physical interval 147.74Mb-148.46Mb, marker interval 3330-3331) were used to validate the association between genotype and sucrose content. Results showed that genotypes carrying the CC allele exhibited significantly higher sucrose content than those with the TT genotype (Figure 5). The genotypes of each material and the statistical results of sucrose content are shown in Table 6. For the materials with the genotype CC, SC ranged from 53.41mg/g to 88.52mg/g, with an average of 68.35mg/g. For the material with the genotype TT, SC ranged from 11.04mg/g to 38.78mg/g, with an average of 24.63mg/g (Table 6). The SC of the materials with the CC genotype was significantly different from that of materials with the TT genotype, and the genotype–phenotype correspondence was consistent. These results indicate that the developed KASPs can effectively screen TSC, SSC, and SC in peanuts.

Figure 5. KASP-SC genotyping results and their performance in extreme peanut materials. (B) The blue clustered points represent the CC genotype, and the red clustered points represent the TT genotype. (A) Box plot of Sucrose content (mg/g) in peanut accessions with the CC and TT genotypes. (B) Allele discrimination plot from KASP genotyping of peanut accessions.

4 Discussion

4.1 The impact of the environment on sugar content

The sugar content in peanut is substantially influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, light, and soil. Specifically, low-temperature environments in cold regions have positively affected sugar accumulation in peanut seeds (Wang et al., 2021). Furthermore, extending light exposure can significantly increase the accumulation of photosynthetic products in leaves, thereby supplying more substrates for sugar synthesis in the seeds (Chen et al., 2020). Soil potassium enrichment also contributes positively, leading to a significant increase in seed sugar content (Abo El-Kasem et al., 2025). Consequently, peanuts cultivated in cold regions typically exhibit higher sugar levels.

Despite experiencing lower temperatures and more favorable light conditions during kernel maturation than Baoding, Fuxin consistently showed lower TSC, SSC, and SC in fresh peanut seeds. This indicates that the relationship between these environmental factors and sugar accumulation in peanuts is complex and may involve other influencing variables. Soil conditions may exert a greater influence than temperature and light. Future studies should integrate meteorological conditions, soil, and other factors to clarify the environmental factors that affect sugar content and identify the differential responses of peanut germplasm with varying sugar levels to temperature and light. This will also provide a theoretical basis for region-specific peanut cultivation aimed at optimizing sugar content.

Interestingly, while lines with low TSC, SSC, and SC of DMS in Fuxin exhibited higher levels than in Baoding, those with higher sugar content displayed the opposite trend. Previous studies have shown that the drying process affects the quality of peanuts and involves genotypic differences (Deng et al., 2025). According to the historical meteorological data, temperatures in Fuxin are lower than those in Baoding during mid-to-late September. During this period of peanut dehydration and drying, the physiological and biochemical activity inside the seeds is vigorous, and it is the key period for sugars to be converted into storage substances such as oil and protein. Low temperature reduces the physiological and biochemical metabolism rate, and the conversion process is hindered. This may be the reason why the DMS sugar content in Fuxin was found to be higher than that in Baoding. Germplasm with high sugar content may be predominantly affected by genetic factors and less by environmental factors. The genetic differences in sugar content during the drying period warrant further investigation.

4.2 The effect of the drying process on sugar content

The sugar content of FS is mainly influenced by the expression of metabolic genes active during different stages of seed development. The sugar content of DMS is not only affected by the expression of genes related to each developmental stage, but also by the expression of genes during the drying process. The results of this study demonstrated that sugar content in both FS and DMS is genotype-dependent. DMS represents the physiological maturation of FS after drying; therefore, the QTLs affecting DMS sugar content are more complex. This study conducted QTL analysis on the sugar content of FS and DMS using an RIL population. The qSB06 affecting SC-DMS, TFC, and SSC in both FS and DMS was a key locus for sugar synthesis. The QTLs of SC-FS differed completely from those in DMS, likely reflecting the distinct physiological role of sucrose in the source–sink dynamics of plants. Sucrose is a product of photosynthesis and the principal transported carbohydrate. After reaching the sink, it can be hydrolyzed into hexoses, which enter the tricarboxylic acid pathway for protein and oil conversion. It may also be converted into polysaccharides such as cellulose and starch (Xu et al., 2025). The final content in FS is therefore largely determined by the genotype. Future research should further dissect the functional differences among QTLs in FS and DMS in order to clarify the key sugar metabolism pathways in FS and DMS.

4.3 Novel QTLs identified for sugar content in peanut

Recent studies have explored sugar content traits in mature peanut kernels, using QTL mapping and GWAS analyses to explore the regions and genes related to sugar content traits in peanuts (Zhang et al., 2023). This study identified 22 and 11 QTLs in DMS and FS, respectively, through QTL mapping. The main QTL locus qSA06, located on chromosome A06, associated with total sugar, soluble sugar, and sucrose content, overlaps with the QTL located by Huai et al. (2024), which were associated with sucrose and oil content. The other major QTL, qSB06, identified in this study, is a newly identified locus associated with total sugar content, soluble sugar content, and sucrose content, and has been detected in DMS and FS across multiple environments. This interval includes a 722 kb region and 56 genes. A major QTL linked to SC was identified in FS, located on chromosome A02, explaining11.67% of the phenotypic variation. Collectively, these QTLs provide valuable targets for breeders to simultaneously or separately optimize sugar content in FS and DMS.

4.4 Candidate genes in the major QTL region on chromosome B06

Although the major QTL region on chromosome B06 spanned a relatively large physical interval (~0.72 Mb), candidate genes could still be preliminarily identified. Using reference genome annotations and existing transcriptome data (Wang et al., 2024), three genes (arahy.3URM83, arahy.41Y8R9, arahy.P7PTW7) were identified as potential candidate genes influencing sugar content. Arahy.3URM83 encodes an exo70 family protein of the outer capsule subunit, and its expression pattern during seed drying exhibits an initial increase followed by a decrease. Dong et al. (2023) identified and performed a genome-wide characterization of the cotton EXO70 gene family, and found that EXO70 in cotton is related to fiber quality, and upland cotton with a greater EXCO70 gene copy number is more sensitive to environmental stress. Wang et al. (2016) found that silencing certain EXCO70 genes in soybean could inhibit the formation of root nodules and promote premature aging of leaves. Overexpression of EXCO70 in Arabidopsis thaliana revealed that it could affect leaf and flower development. Therefore, it is speculated that it plays an important role in growth and development in leguminous plants by affecting protein and nutrient transport in vesicles. Homologous genes have also been implicated in the negative regulation of sucrose content.

Arahy.41Y8R9 is a growth regulatory factor (GRF) gene whose expression level during peanut drying decreases initially and then increases, opposite to arahy.3URM83. The resequencing results revealed allelic variation between the parents, with a C-to-A substitution at the 460th base in Silihong. Zhao et al. (2019) identified the GRF gene family in cultivated peanuts, which were distributed on 20 chromosomes. The expression levels of AhGRF5a and AhGRF5b genes in pod tissues are higher than those in root, leaf, and stem tissues. Multiple genes of the peanut GRF family were found to be involved in grain growth and development. Therefore, it can be inferred that this gene may positively regulate sugar accumulation.

Arahy.P7PTW7 is annotated as a Syntaxin/t-SNARE family protein involved in vesicle-mediated transport. Rui et al. (2022) conducted functional studies on the Arabidopsis thaliana T-SNARE protein SYP31/SYP32 gene and found that this gene is involved in regulating COPI vesicle-mediated reverse transport and maintaining Golgi apparatus morphology, and plays a role in the development of Arabidopsis male gametophytes. Zhang et al. (2016) identified and examined the biological function of the SNARE protein FgVam7 binding protein in wheat, and found that the SNARE protein FgPep12 participates in regulating the growth, development, and pathogenicity of Fusarium graminearum by participating in vesicle transport. In this study, a base deletion at position 725 was identified in Jinonghei3. The above three genes are closely associated with the transportation and storage of sugars and exhibit sequence variation between the parents. The specific genetic mechanisms involved in regulating sugar synthesis and transport in peanuts need to be further explored.

5 Conclusion

In this study, 22 and 11 QTLs related to sugar content in DMS and FS were identified respectively through QTL mapping. Among these, qA06 (physical location 115.08-115.73 Mb) and qB06 (physical location 147.74-148.46 Mb) were two major co-localized QTLs identified in multiple environments. KASP markers based on the arahy.PKWB63 were developed for qB06 to support marker-assisted selection. Candidate genes (arahy.3URM83, arahy.41Y8R9, arahy.P7PTW7) linked to sugar metabolism were identified, pending functional validation. These findings provide a theoretical basis for peanut breeding aimed at improving sugar content, flavor, and industrial quality.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

CZ: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. ML: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. SC: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HD: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LL: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. YL: Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. XL: Writing – review & editing, Software, Supervision, Visualization. XC: Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was financially sponsored by the Hebei Agriculture Research System (HBCT2024040205); the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-13); Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province(C2022204145); the National Key Research and Development Program of seed industry technology innovation team of Hebei province (21326316D-2); S&T Program of Hebei (24466301D).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abo El-Kasem, R., Noufal, E. H., Farid, I. M., Habashy, N., and Abbas, H. (2025). Can Potassium, Amino Acids, and Yeast Foliar Applications Enhance Growth, Nutrient and Biochemical Contents of Peanut (Arachis hypogaea) Grown on a Calcareous Soil under Salinity Stress? Environment Biodiversity Soil Secur. 9, 51–66. doi: 10.21608/jenvbs.2025.362795.1265

Bhat, R. S., Shirasawa, K., Gangurde, S. S., Rashmi, M. G., Sahana, K., and Pandey, M. K. (2023). Genome-wide landscapes of genes and repeatome reveal the genomic differences between the two subspecies of peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Crop Design. 2, 100029. doi: 10.1016/j.cropd.2023.100029

Chen, T., Zhang, H., Zeng, R., Wang, X., Huang, L., Wang, L., et al. (2020). Shade effects on peanut yield associate with physiological and expressional regulation on photosynthesis and sucrose metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 5284. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155284

Chen, M., Hou, M., Cui, S., Li, Z., Mu, G., Liu, Y., et al. (2022). Construction of near-Infrared models for sugar content in peanuts with different seed coat colors. Spectrosc. Spectral Anal. 42, 2896–2902. doi: 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2022)09-2896-07

Deng, J., Hou, M., Cui, S., Liu, Y., Li, X., and Liu, L. (2025). Integrative analysis of transcriptome and metabolome reveals molecular mechanisms of dynamic change of storage substances during dehydration and drying process in peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L.). Front. Plant Sci. 16. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1567059

Dong, Y. Y., Xu, B. Y., Dong, Z. Y., Wang, L. Y., Chen, J. W., and Fang, L. (2023). Genome-wide identification and interspecific comparative analysis of the EXO70 gene family in cotton. Scientia Agricultura Sin. 56, 4621–4634. doi: 10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2023.23.005

Guo, J. B., Li, W. T., Liu, N., Luo, H. Y., Ding, Y. B., Yu, B. L., et al. (2023). Correlation analysis of sucrose content with protein and oil content and QTL mapping of sucrose content in peanut. Acta Agronomica Sin. 49, 2698–2704. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2023.24251

Guo, J., Qi, F., Qin, L., Zhang, M., Sun, Z., Li, H., et al. (2023). Mapping of a QTL associated with sucrose content in peanut kernels using BSA-seq. Front. Genet. 13. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.1089389

Hou, M., Mu, G., Zhang, Y., Cui, S., Yang, X., and Liu, L. (2017). Evaluation of total flavonoid content and analysis of related EST-SSR in Chinese peanut germplasm. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 17, 221–227. doi: 10.1590/1984-70332017v17n3a34

Huai, D., Zhi, C., Wu, J., Xue, X., Hu, M., Zhang, J., et al. (2024). Unveiling the molecular regulatory mechanisms underlying sucrose accumulation and oil reduction in peanut kernels through genetic mapping and transcriptome analysis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 208, 108448. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.108448

Li, X., Hao, J., Deng, H., Cui, S., Li, L., Hou, M., et al. (2024). Identification of a pleiotropic QTL and development KASP markers for HPW, HSW, and SP in peanut. J. Integr. Agric. doi: 10.1016/j.jia.2024.06.013

Li, X., Zhao, X., Sun, S., Tao, K., and Niu, Y. (2025). Meta-QTL analysis and genes responsible for plant and ear height in maize (Zea mays L.). Plants. 14, 1943. doi: 10.3390/plants14131943

Li, W., Huang, L., Liu, N., Chen, Y., Guo, J., Yu, B., et al. (2023). Identification of a stable major sucrose-related QTL and diagnostic marker for flavor improvement in peanut. Theor. Appl. Genet. 136, 78. doi: 10.1007/s00122-023-04306-0

Liang, W. Z., Kirk, K. R., and Thomas, J. (2018). “Estimation of peanut maturity using color image analysis,” in 2018 ASABE annual international meeting (St. Joseph, Michigan: American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers). doi: 10.13031/aim.201801669

Park, K. J., Sa, K. J., Koh, H. J., and Lee, J. K. (2013). QTL analysis for eating quality-related traits in an F2: 3 population derived from waxy corn× sweet corn cross. Breed. Sci. 63, 325–332. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.63.325

Pattee, H. E., Isleib, T. G., Giesbrecht, F. G., and McFeeters, R. F. (2000). Relationships of sweet, bitter, and roasted peanut sensory attributes with carbohydrate components in peanuts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48, 757–763. doi: 10.1021/jf9910741

Qu, C., Li, Z., Yang, Q., Wang, X., and Wang, D. (2022). Effect of drying methods on peanut quality during storage. J. Oleo Sci. 71, 57–66. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess21146

Rui, Q., Tan, X., Liu, F., and Bao, Y. (2022). An update on the key factors required for plant Golgi structure maintenance. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.933283

Wang, F., Miao, H., Zhang, S., Hu, X., Li, C., Chu, Y., et al. (2024). Identification of a major QTL underlying sugar content in peanut kernels based on the RIL mapping population. Front. Plant Sci. 15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1423586

Wang, F., Miao, H., Zhang, S., Hu, X., Li, C., Yang, W., et al. (2025). Identification of a new major oil content QTL overlapped with FAD2B in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Plants. 14, 615. doi: 10.3390/plants14040615

Wang, W., He, A., Peng, S., Huang, J., Cui, K., and Nie, L. (2018). The effect of storage condition and duration on the deterioration of primed rice seeds. Front. Plant Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00172

Wang, X., Liu, Y., Han, Z., Chen, Y., Huai, D., Kang, Y., et al. (2021). Integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics analysis reveal key metabolism pathways contributing to cold tolerance in peanut. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.752474

Wang, Z., Li, P., Yang, Y., Chi, Y., Fan, B., and Chen, Z. (2016). Expression and functional analysis of a novel group of legume-specific WRKY and Exo70 protein variants from soybean. Sci. Rep. 6, 32090. doi: 10.1038/srep32090

Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Huai, D., Chen, Y., Wang, X., Kang, Y., et al. (2024). Detection of two homologous major QTLs and development of diagnostic molecular markers for sucrose content in peanut. Theor. Appl. Genet. 137, 61. doi: 10.1007/s00122-024-04549-5

Wu, W. Y., Chen,, L., Liang, R. T., Huang, S. P., Li, X., Huang, B. L., et al. (2025). The role of light in regulating plant growth, development and sugar metabolism: A review. Frontiers in Plant Science 15, 1507628.

Xu, Y., Liu, S., Sun, H., Zang, J., Zhang, C., Guo, W., et al. (2025). Sucrose transport gene FaSWEET9a regulated by FaDOF2 transcription factor promotes sucrose accumulation in strawberry. Plant Cell Rep. 44, 138. doi: 10.1007/s00299-025-03528-4

Zhang, H., Dean, L., Wang, M. L., Dang, P., Lamb, M., and Chen, C. (2023). GWAS with principal component analysis identify QTLs associated with main peanut flavor-related traits. Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1204415

Zhang, H., Li, B., Fang, Q., Li, Y., Zheng, X., and Zhang, Z. (2016). SNARE protein FgVam7 controls growth, asexual and sexual development, and plant infection in Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 17, 108–119. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12267

Zhao, K., Li, K., Ning, L., He, J., Ma, X., Li, Z., et al. (2019). Genome-wide analysis of the growth-regulating factor family in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4120. doi: 10.3390/ijms20174120

Keywords: drying maturation seed, fresh seed, KASP, peanut, QTL, sugar content

Citation: Zhang C, Liu M, Cui S, Chen M, Deng H, Liu L, Liu Y, Li X, Chen X and Hou M (2026) Identification of novel QTLs and development of KASP markers for sugar content in fresh and dried peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Front. Plant Sci. 16:1745366. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1745366

Received: 13 November 2025; Accepted: 22 December 2025; Revised: 21 December 2025;

Published: 22 January 2026.

Edited by:

Kun Lu, Southwest University, ChinaReviewed by:

Jiban Shrestha, Nepal Agricultural Research Council, NepalMarco Goyzueta Altamirano, University of Florida, United States

Copyright © 2026 Zhang, Liu, Cui, Chen, Deng, Liu, Liu, Li, Chen and Hou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mingyu Hou, aG91bXlAaGViYXUuZWR1LmNu; Lifeng Liu, bGl1bGlmZW5nQGhlYmF1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Chi Zhang

Chi Zhang Mingshuo Liu1,2†

Mingshuo Liu1,2† Hongtao Deng

Hongtao Deng Yingru Liu

Yingru Liu Mingyu Hou

Mingyu Hou