- 1College of Landscape Architecture, Jiangsu Vocational College of Agriculture and Forestry, Zhenjiang, China

- 2College of Forestry, Beihua University, Jilin, China

- 3College of Forestry, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, Henan, China

Introduction: Proline-rich extensin-like receptor kinases (PERKs) represent a distinct subclass of plant receptor-like kinases (RLKs) ubiquitous in plants. While characterized in several species, a comprehensive analysis of the PERK gene family in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) remains limited.

Methods: A genome-wide identification and systematic characterization of the PERK gene family in peanut was conducted. Evolutionary analysis was performed via phylogenetics and motif identification. Gene structures and promoter cis-elements were analyzed in silico. Expression profiles were assessed across tissues and under abiotic stresses. Functional validation of selected genes in plant innate immunity was performed.

Results: Twenty-three PERK genes (PERK1-PERK23) were identified, unevenly distributed across 12 chromosomes (highest density on chromosome 5). Phylogenetic analysis with Arabidopsis PERKs classified them into three subgroups (I-III), with Subgroup II predominantly containing peanut members. All genes contain introns and share conserved motifs. Promoter analysis revealed stress-responsive elements, including light-responsive (all genes), MeJA-responsive (18 genes), and ABA-responsive (16 genes) elements. Expression profiling showed constitutive expression for 11 genes, ubiquitous high expression of PERK6/PERK20, and root/nodule-specific expression of PERK13/PERK14. Under abiotic stress, 12, 9, and 6 genes responded to low temperature, drought, and ABA, respectively. Functionally, PERK4, PERK12, and PERK15 significantly suppressed plant innate immunity, whereas PERK8 enhanced it.

Discussion: This study provides the first genome-wide analysis of the PERK family in peanut, revealing its evolutionary features and expression patterns. Crucially, functional characterization demonstrates that peanut PERKs can bidirectionally modulate plant innate immunity, with members acting as either negative or positive regulators. This discovery of their immune regulatory functions offers novel molecular targets for stress-resistance breeding in legume crops.

1 Introduction

Receptor kinases represent expansive gene families ubiquitously present across diverse plant species, including model systems such as Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana. The Arabidopsis genome encodes approximately 600 receptor kinase members, with functional homologs identified and characterized in approximately 20 plant species (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001a; Morris and Walker, 2003; Shiu et al., 2004). While the precise biological roles of most receptor kinases remain to be fully elucidated, they are established as pivotal regulators in diverse physiological processes, encompassing signal transduction pathways, environmental stress adaptation, hormone signaling cascades, plant growth and development, self-incompatibility mechanisms, cell differentiation programs, as well as symbiotic interactions and pathogen recognition (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001b; Diévart and Clark, 2004). The extracellular domains of receptor kinases exhibit specificity for binding diverse ligands, including steroids, peptides, carbohydrates, and cell wall components. Signal transduction across the plasma membrane is facilitated through conserved signaling complexes shared among eukaryotic cells, with the evolutionary origins of these receptors potentially traceable to the early emergence of multicellular organisms (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001a, b).

Receptor kinases are systematically classified into distinct categories based on characteristic extracellular domain motifs (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001b, 2003). Leucine-rich repeat (LRR) receptor kinases, for instance, constitute the largest class in Arabidopsis and include canonical brassinosteroid (BR) sensors such as BRI1 and BAK1 (Li and Chory, 1997; Li et al., 2002; Nam and Li, 2002). These kinases are indispensable for plant immunity; for example, LRR-containing FLS2 recognizes the conserved bacterial flagellin peptide flg22, triggering early immune defense responses such as ROS burst (Bauer et al., 2001; Zipfel et al., 2004). Functional redundancy, often arising from gene duplication events, is a common feature across different receptor kinase classes (Champion et al., 2004), exemplified by functionally overlapping CLV1 and ERECTA receptor kinases (Diévart et al., 2003; Shpak et al., 2003, 2004). PERKs constitute another significant subclass within the broader receptor kinase superfamily. The Arabidopsis PERK family exhibits its highest sequence similarity to Brassica napus PERK1, which is rapidly induced in response to wounding and in the presence of the pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Silva and Goring, 2002). Fifteen PERK members have been annotated within the Arabidopsis genome, although their detailed biological functions remain largely unexplored (Silva and Goring, 2002; Nakhamchik et al., 2004). Arabidopsis PERK1 localizes to the plasma membrane, and its expression is rapidly induced by mechanical wounding (Silva and Goring, 2002). Furthermore, PERK4 was identified as a novel regulator of Ca²+signaling, mediating early events in ABA-responsive root tip growth inhibition (Bai et al., 2009a, b). Recent data showed that PERK expression is also regulated in response to environmental cues. AtPERK13 is induced under phosphate, nitrogen and iron deprivations (Xue et al., 2021). PERK expression in Gossypium hirsutum is sensitive to, and generally downregulated by heat, cold, salt or drought (Qanmber et al., 2019). An exposition to a moderately low temperature leads to an expression change of a rice PERK gene, Z15 (Feng et al., 2019). These findings collectively underscore the functional versatility of the PERK gene family in regulating fundamental plant life processes.

Advances in genome sequencing technologies have enabled systematic identification of PERK gene families across multiple plant species. While fifteen members have been confirmed in Arabidopsis, thirty-three were identified in cotton (G. hirsutum) (Qanmber et al., 2019). Cultivated peanut (A. hypogaea L.), an allopolyploid leguminous crop valued for its high oil and protein content, is predominantly cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions (Jiang et al., 2021). Current genomic evidence supports an evolutionary origin involving hybridization between two diploid progenitors (Arachis duranensis and Arachis ipaensis) followed by chromosomal duplication (Seijo et al., 2007). Breeding disease-resistant, stress-tolerant, and high-quality varieties represents a critical strategy to mitigate production constraints. Systematic investigations into the role of the PERK gene family in disease and stress resistance within peanut remain notably absent. As an allotetraploid species, peanut has undergone complex genome evolution, typically resulting in larger gene family sizes compared to diploid model plants (Huang et al., 2022). Therefore, comprehensive identification of peanut PERK family members and elucidation of their evolutionary relationships and expression dynamics are crucial prerequisites for uncovering the molecular mechanisms underpinning stress tolerance. Concurrently, the functional association between the PERK gene family and disease resistance pathways remains poorly characterized in peanut.

This study employs the peanut cultivar ‘Fuhuasheng’ to systematically identify and characterize the PERK gene family in peanuts. We aim to investigate the evolutionary features, expression patterns, and potential functional roles of these genes in development and stress responses. Furthermore, we seek to explore their involvement in the regulation of plant immunity. The findings are expected to provide insights into the functional diversification of PERK genes and offer potential genetic targets for stress-resistance breeding in legume crops.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant materials

The peanut cultivar ‘Fuhuasheng’, utilized throughout this study, has undergone comprehensive whole-genome assembly and sequencing. Its publicly available reference genome database (Peanut Genome Resource, PGR: https://pgr.itps.ncku.edu.tw) served as the primary resource for in silico analyses. For experimental studies, ‘Fuhuasheng’ plants were cultivated in a growth chamber under a 14-h light/10-h dark (25 °C) photoperiod, with a light intensity of 350 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ and 60-70% relative humidity. Plants were grown in a standard peat-based potting mix.

Nicotiana benthamiana and A. thaliana (Col-0) plants were maintained in a controlled-environment growth room at 22 °C with 70% relative humidity and a 14-h light/10-h dark photoperiod. A light intensity of 120 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ was provided by cool-white fluorescent lamps. N. benthamiana plants were grown in a commercial potting soil mixture and used for transient expression assays at the 4–5 leaf stage. Arabidopsis plants grow on a 1:1 mixture of peat moss and vermiculite, and are used for Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation after flowering.

2.2 Identification of PERK family members

The complete genome sequence, annotation files, and gene structure information (introns, exons, coding sequences - CDS) for peanut were retrieved from the public PGR database. Full-length protein sequences corresponding to the 15 known Arabidopsis thaliana PERK genes (AtPERKs) served as query sequences for BLASTP searches against the peanut genome protein annotation dataset (Altschul et al., 1997). Structural characteristics of Arabidopsis PERK family are provided in Supplementary Table S1. Following removal of redundant sequences, candidate PERK homologs were validated using the SMART database to confirm the presence of characteristic PERK domain architecture prior to subsequent analyses (Letunic and Bork, 2018).

2.3 Sequence analysis and chromosomal localization of PERKs

Chromosomal positions and protein lengths of identified PERK genes were extracted directly from the PGR database annotations. Key physicochemical parameters of the deduced PERK proteins, including molecular weight and theoretical isoelectric point (pI), were calculated using the ExPASy Compute pI/Mw tool (https://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/; accessed on 20 June 2025). Subcellular localization predictions were generated using the DeepLoc-2.1 server (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/DeepLoc-2.1/; accessed on 23 December 2025).

2.4 Phylogenetic analysis and classification of PERKs

Multiple sequence alignment of the full-length amino acid sequences derived from the 23 identified AhPERKs and the 15 AtPERKs was performed using ClustalW (https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw; accessed on 1 July 2025) (Thompson et al., 1994). A maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 10.2 software (Kumar et al., 2018), with branch support assessed by 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

2.5 Analysis of PERK structural features

Conserved protein motifs within the PERK sequences were identified using the MEME suite (v5.3.3; https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme; accessed on 1 July 2025) (Bailey et al., 2009) employing default search parameters. Exon-intron structural organization information for each PERK gene was extracted directly from the PGR database annotations.

2.6 Analysis of Cis-acting elements in PERK gene promoters

To investigate potential regulatory elements, a 2.0-kb genomic region immediately upstream of the translation initiation codon (ATG) for each PERK gene was extracted utilizing TBtools software (Chen et al., 2020). Putative cis-acting elements within these promoter sequences were identified and functionally annotated using the PlantCARE online platform (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/; accessed on 5 July 2025) (Lescot et al., 2002).

2.7 Analysis of PERK gene expression patterns

Publicly available transcriptome datasets hosted within the PGR database were analyzed to determine PERK gene expression patterns across diverse tissues and under various stress conditions. Tissue samples analyzed included: Root, Root tip, Root nodule, Root and stem, Stem, Stem tip, Cotyledon, Leaf, Florescence (full flowering), Gynophore, Pericarp-I, Pericarp-II, Pericarp-III, Embryo-I, Embryo-II, Embryo-III, Embryo-IV, Testa-I, and Testa-II.

Stress treatments comprised: drought stress (normally irrigated leaves vs. drought-treated leaves), hormone treatments (ddH2O-, salicylic acid (SA)-, paclobutrazol (PAC)-, ethephon (ETH)-, brassinolide (BL)-, or abscisic acid (ABA)-treated leaves), and temperature stress (room temperature control leaves vs. low-temperature-treated leaves).

2.8 ROS detection assay

Full-length coding sequences of selected PERK genes were amplified via PCR and subsequently cloned into the pCAMBIA1300-35S-HA-RBS expression vector for Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain GV3101)-mediated transient expression in mature leaves of 5- to 6-week-old N. benthamiana plants. Forty-eight hours post-infiltration, leaf discs (8 mm diameter) were excised using a sterile cork borer (Sigma-Aldrich) and equilibrated overnight in 200 μL of ultrapure water within 96-well plates. Discs were subsequently challenged with 200 μL of reaction buffer containing 20 μM L-012 (Wako Chemicals), 10 μg/mL horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 μM flg22 peptide. Luminescent signals generated by ROS production were quantified at 30-second intervals for a duration of 15 minutes using a Tecan F200 microplate reader. Three independent biological replicates were analyzed per construct, with statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05).

2.9 Pathogen infection assays

In the Pst DC3000 infection experiments, Arabidopsis plants cultivated in soil for 4–5 weeks were used. Bacterial suspensions at a concentration of 5 × 108 CFU/mL were sprayed onto the leaves. Bacterial titers were assessed 3 days after inoculation.

2.10 RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from Arabidopsis tissues employing the Plant Total RNA Kit (ZomanBio, Beijing, China). Subsequently, first-strand cDNA was reverse-transcribed using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was carried out with SYBR® Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR Kit (Accurate, Changsha, China) on an ABI QuantStudio 6 Flex instrument. All primer sequences utilized in this study are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

3 Results

3.1 Identification of PERK subfamily members and analysis of protein physiochemical properties in peanut

Systematic interrogation of the peanut genome annotation file using the BLASTP algorithm led to the identification of 23 PERK family members. These were designated PERK1 to PERK23 based on their sequential chromosomal locations (Table 1). Comprehensive characterization of these 23 PERK genes was performed, encompassing amino acid sequence length, predicted protein molecular weight (MW), theoretical isoelectric point (pI), and subcellular localization (Table 1). Results revealed moderate diversity in protein length, ranging from 503 amino acids (PERK14) to 761 amino acids (PERK19). Corresponding molecular masses varied from 55.18 kDa (PERK14) to 79.24 kDa (PERK16). Theoretical pI values spanned a broad range from 5.46 (PERK21) to 9.34 (PERK5), suggesting functional diversity. Subcellular localization predictions unanimously indicated cell membrane and/or lysosome/vacuole distribution for all PERK proteins. Detailed characteristics of the 23 PERK gene family members are compiled in Table 1.

3.2 Chromosomal distribution of PERK subfamily members in peanut

Chromosomal positional information for the 23 PERK genes was retrieved from the PGR database (Table 1). Localization analysis demonstrated that these genes are widely, yet unevenly, distributed across the peanut genome. They are located on 12 specific chromosomes: Chr03, Chr04, Chr05, Chr07, Chr09, Chr10, Chr13, Chr14, Chr15, Chr17, Chr19, and Chr20. The distribution density among chromosomes was highly asymmetric. Chromosome 5 harbored the highest number of PERK genes (5 genes), indicative of a region of elevated density. Chromosomes 14 and 15 each contained 4 PERK genes. Chromosome 10 possessed 2 PERK genes. The remaining chromosomes (Chr03, Chr04, Chr07, Chr09, Chr13, Chr17, Chr19, Chr20) each contained only a single PERK gene, signifying regions of sparse PERK gene distribution (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Chromosomal localization of PERK gene family members in peanut. 23 members were mapped to 12 chromosomes.

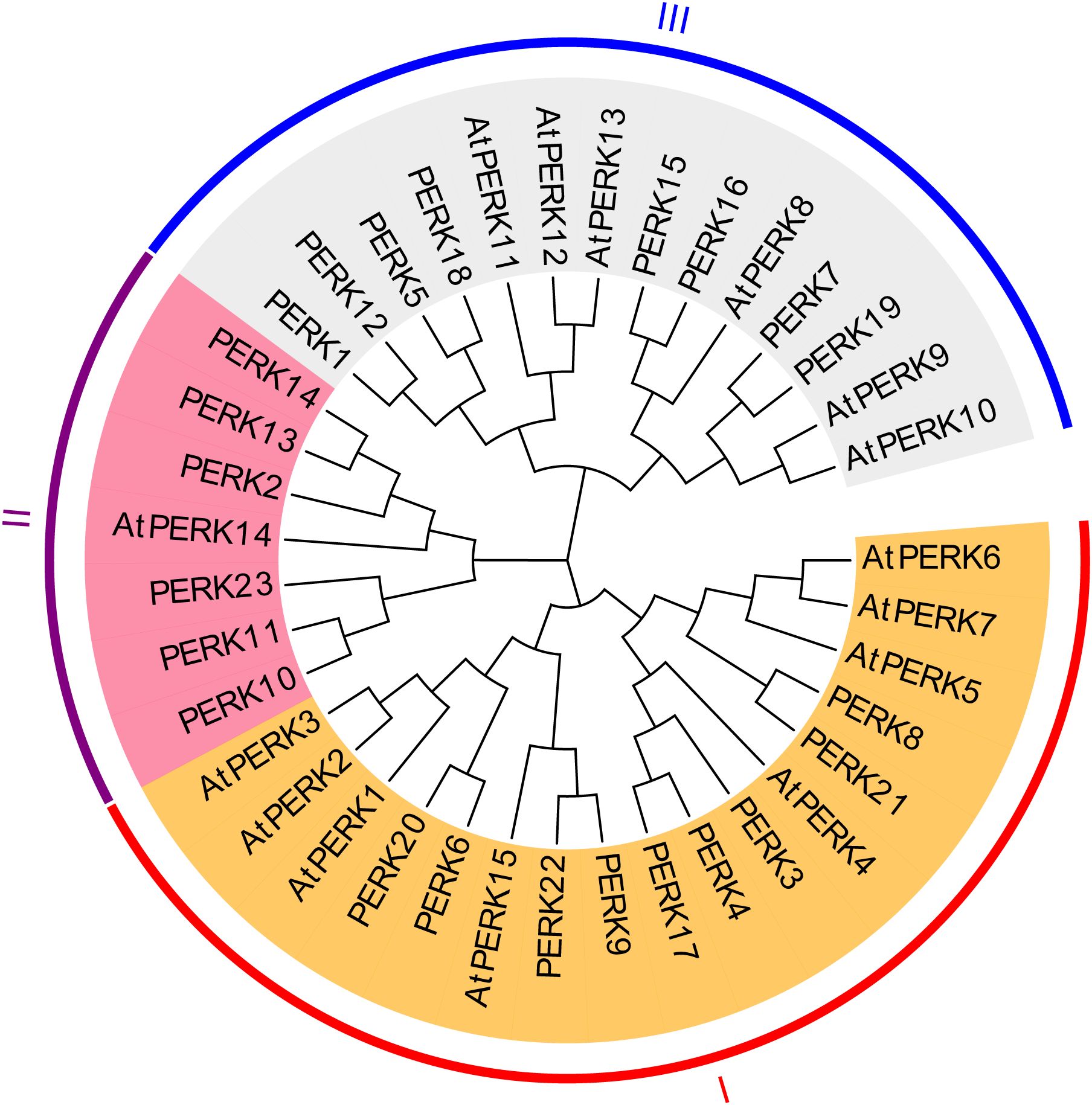

3.3 Phylogenetic analysis of the peanut PERK family

To elucidate the evolutionary relationships between peanut and Arabidopsis PERK genes, a maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was constructed based on multiple sequence alignments of the full-length amino acid sequences of the 23 peanut PERK proteins and 15 Arabidopsis PERK proteins. Based on sequence similarity and phylogenetic topology, the peanut PERK genes were resolved into three primary clades, designated Group I, Group II, and Group III. As depicted in Figure 2, Group I comprised 9 peanut PERK proteins and 8 Arabidopsis PERK proteins. Group II contained 6 peanut PERK proteins and 1 Arabidopsis PERK protein. Group III included 8 peanut PERK proteins and 6 Arabidopsis PERK proteins (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree of PERK proteins from Arabidopsis and peanut. A Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree illustrates evolutionary divergence among 15 Arabidopsis and 23 peanut PERK homologs. Full-length protein sequences were aligned using ClustalW, and the tree was constructed with 1000 bootstrap replicates using MEGA X.

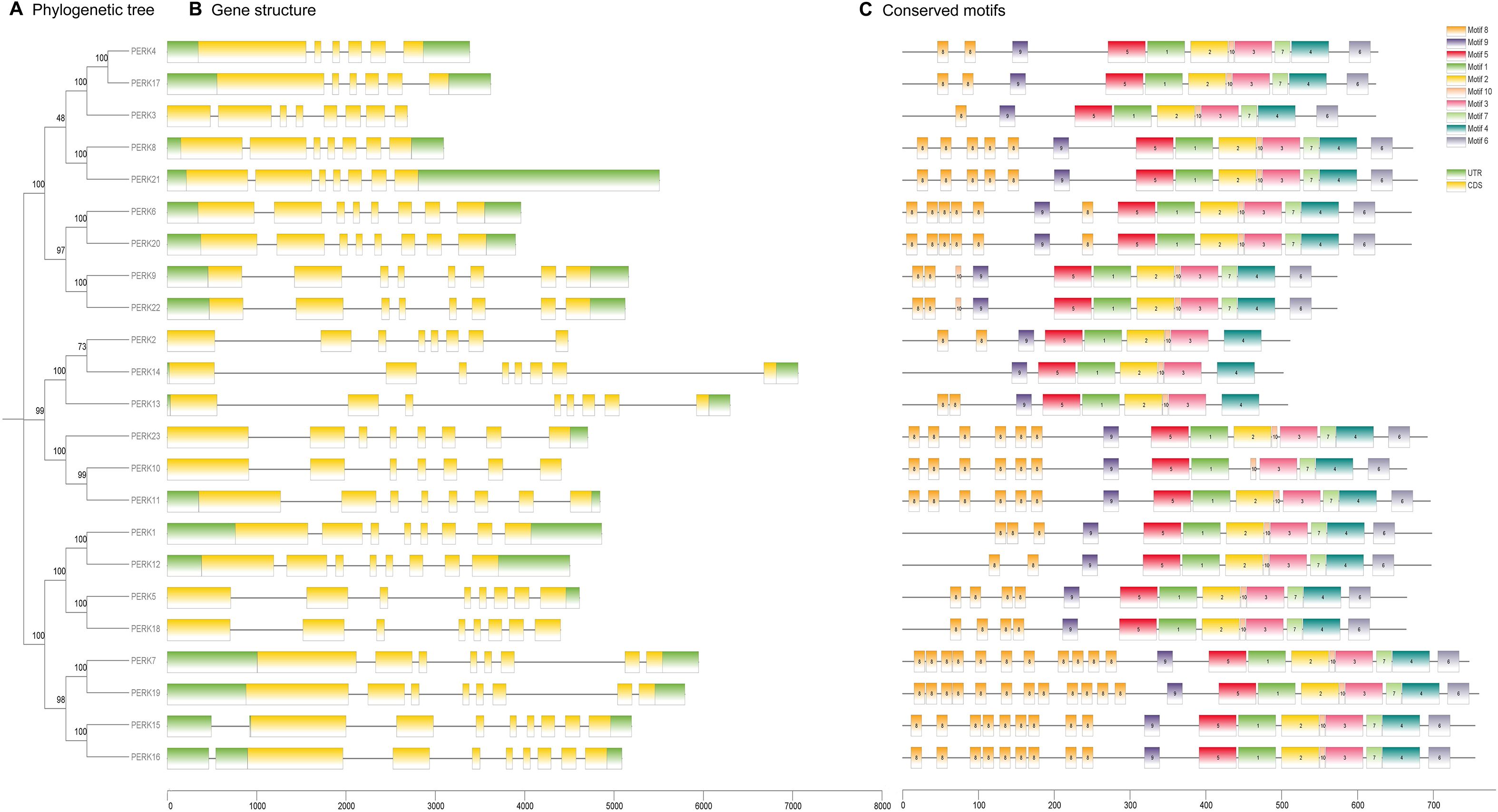

3.4 Analysis of gene structure and conserved protein motif composition in the peanut PERK gene family

To gain insights into the evolutionary dynamics of the PERK gene family in peanut, the exon-intron structures were analyzed in conjunction with a phylogenetic tree constructed from the full-length PERK protein sequences. As shown in Figure 3A, the 23 peanut PERK genes were phylogenetically classified into three distinct subgroups. Gene structure analysis confirmed that all PERK gene family members in peanut contain introns (Figure 3B). The function and structure of PERK proteins are critically dependent on conserved motifs, which play essential roles in protein activity. In-depth motif analysis using the MEME suite identified 10 conserved motifs within the peanut PERK family (Figure 3C). All members possess Motifs 1, 3, 4, 5, 9, and 10. All members except PERK10 contain one instance of Motif 2. Motifs 6 and 7 are absent in PERK2, PERK13, and PERK14 but are present once in all other members. Within the peanut PERK family, all members except PERK14 contain at least one instance of Motif 8. Notably, the copy number of Motif 8 exhibited the greatest variation across family members, suggesting its potential contribution to functional diversification within the family (Figure 3C). The detailed sequences of the six putative motifs are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

Figure 3. Evolutionary relationships (A), gene structure (B), and conserved motifs (C) of PERK family members in Peanut. (A) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of 23 PERK proteins, classified into three distinct clades using MEGA X. (B) Exon-intron architecture of PERK genes. Untranslated regions (UTR) are depicted as green boxes, coding sequences (CDS) as yellow boxes, and introns as gray connecting lines. (C) Conserved protein motif composition identified by MEME suite analysis. Ten motifs (Motif 1–Motif 10) are color-coded to reflect their sequential positions in protein sequences.

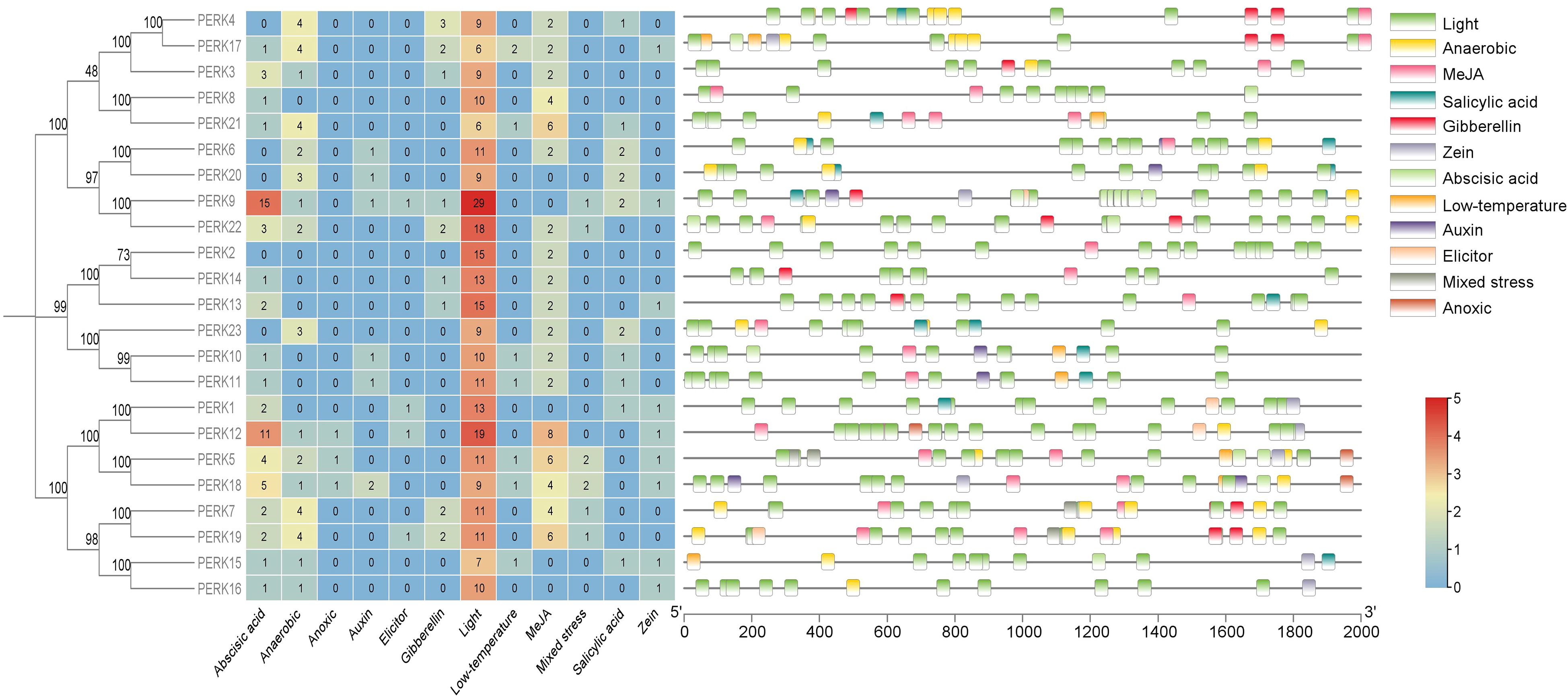

3.5 Analysis of stress-related Cis-acting elements in the promoters of peanut PERK genes

To investigate the potential molecular mechanisms governing peanut PERK gene responses to abiotic stress and phytohormone signaling, a 2.0 kb genomic region upstream of the initiation codon (ATG) for each PERK gene was extracted from the PGR database. These promoter sequences were analyzed using the PlantCARE platform for the identification of stress-associated cis-acting regulatory elements. Analysis identified 12 distinct types of responsive cis-acting elements within the promoters of the 23 peanut PERK genes (Figure 4), encompassing elements associated with ABA response, anaerobic response, mixed stress response, zein response, light response, low-temperature response, MeJA response, salicylic acid (SA) response, auxin response, gibberellin (GA) response, elicitor response, and anoxic response.

Figure 4. Distribution of cis-acting elements in the promoters of PERK genes in peanut. Schematic representation of stress- and hormone-responsive elements relative to the translation start site (TSS, position 0). Element positions were calculated using PlantCARE database annotations, with color-coded boxes denoting distinct regulatory modules.

As illustrated in Figure 4, results demonstrate that all 23 peanut PERK genes harbor at least 2 (PERK2) stress-responsive cis-acting elements, strongly suggesting their functional involvement in stress response. Association with light-responsive elements varied considerably among PERK members, ranging from a minimum of 6 elements (PERK21) to a maximum of 29 elements (PERK9). Critically, all PERK genes possess light-responsive cis-acting elements, representing the most abundant category identified. Furthermore, within the PERK family, only PERK5, PERK12, and PERK18 contain anoxic response elements, which constitute the least frequent stress response element type. Similarly, only four genes (PERK1, PERK9, PERK12, and PERK19) each harbor a single elicitor response-related cis-acting element (Figure 4).

Within the PERK gene family, 18 members contain ABA-responsive cis-acting elements, and 16 members contain anaerobic response-related elements. These elements are likely instrumental in regulating PERK gene expression during ABA signaling and anaerobic responses. Cis-acting elements associated with auxin response, zein metabolism response, low temperature response, SA response, MeJA response, and mixed stress response were identified in 6, 9, 7, 10, 18, and 6 PERK genes, respectively. Nine PERK genes contain one or more GA-responsive cis-acting elements (Figure 4). Collectively, the cis-element analysis strongly suggests potential involvement of all 23 PERK genes in mediating responses to diverse environmental stresses and hormonal cues.

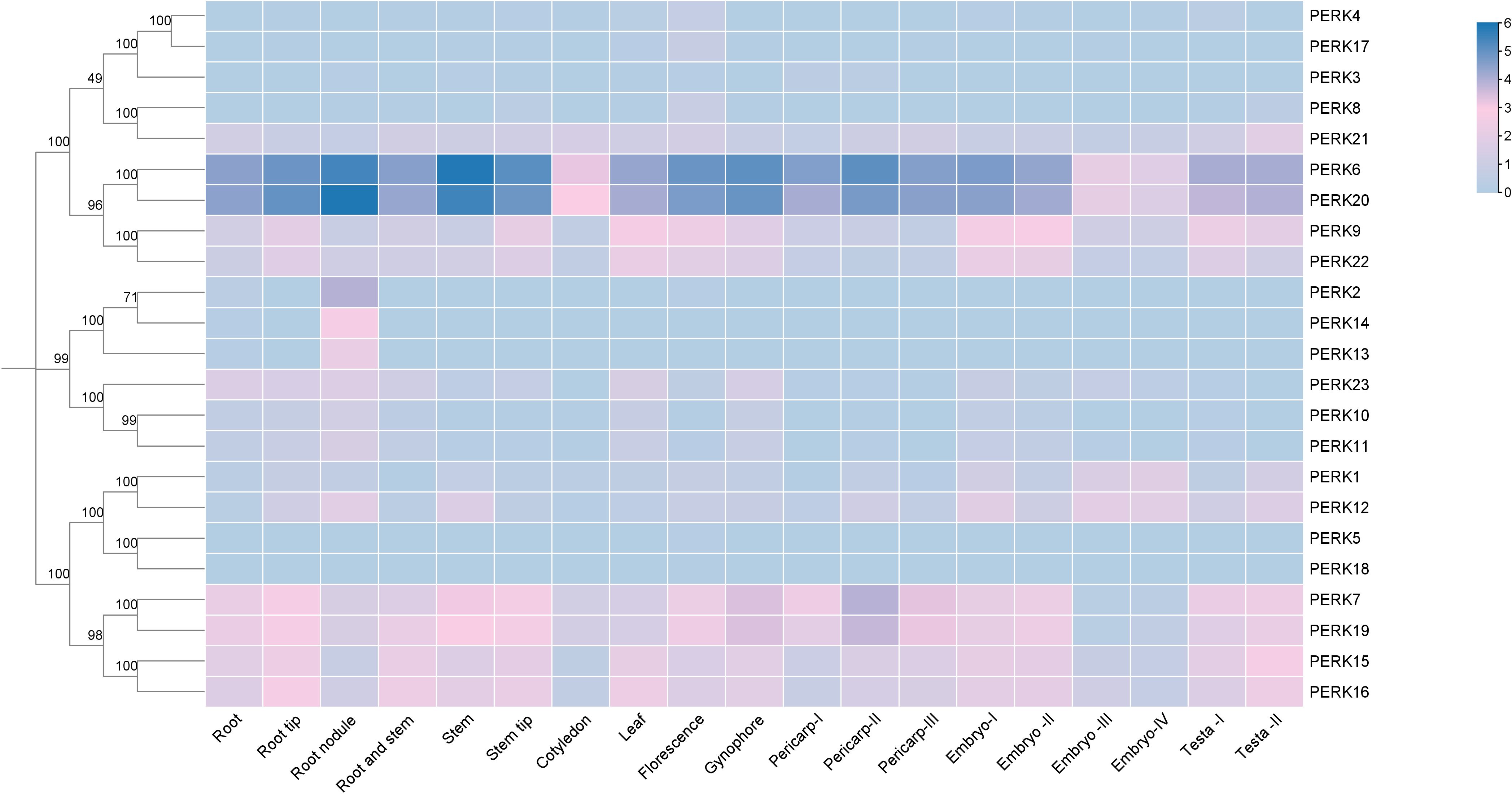

3.6 Expression pattern analysis of peanut PERK genes in different tissues

Genes typically exhibit distinct expression profiles across tissues or organs, reflecting their roles in regulating specific physiological processes. To elucidate the tissue-specific expression patterns of the peanut PERK gene family, transcript abundance (FPKM values) was analyzed across diverse tissues: Root, Root tip, Root nodule, Root and stem, Stem, Stem tip, Cotyledon, Leaf, Florescence, Gynophore, Pericarp-I, Pericarp-II, Pericarp-III, Embryo-I, Embryo-II, Embryo-III, Embryo-IV, Testa-I, and Testa-II. Transcript abundance data for the 23 peanut PERK genes across these tissues are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Heat map showing the expression levels of PERK genes in various tissues of peanut. Tissue-specific expression profiles of PERK genes based on RNA-seq data. Heatmap visualization represents log2-transformed FPKM values averaged across biological replicates. Color gradients indicate low-to-high expression levels, with hierarchical clustering revealing organ-specific expression patterns.

All 23 PERK genes were expressed in at least one examined tissue. Analysis revealed that 11 PERK genes exhibited ubiquitous expression across all tissues analyzed. No family member demonstrated universally high expression (FPKM values > 3). Genes such as PERK6 and PERK20 displayed high expression levels (FPKM values > 3) in the majority of tissues. PERK2, PERK13, PERK14, and PERK18 exhibited highly tissue-specific expression profiles: PERK2 expression was restricted to Root, Root nodule, and Florescence; PERK13 and PERK14 were exclusively expressed in Root and Root nodule; PERK18 was solely detected in Leaf and Florescence (Figure 5). This pronounced tissue specificity suggests potential specialized roles for these genes in regulating functions unique to these organs.

3.7 Expression patterns of PERK genes in response to phytohormone and abiotic stress treatments

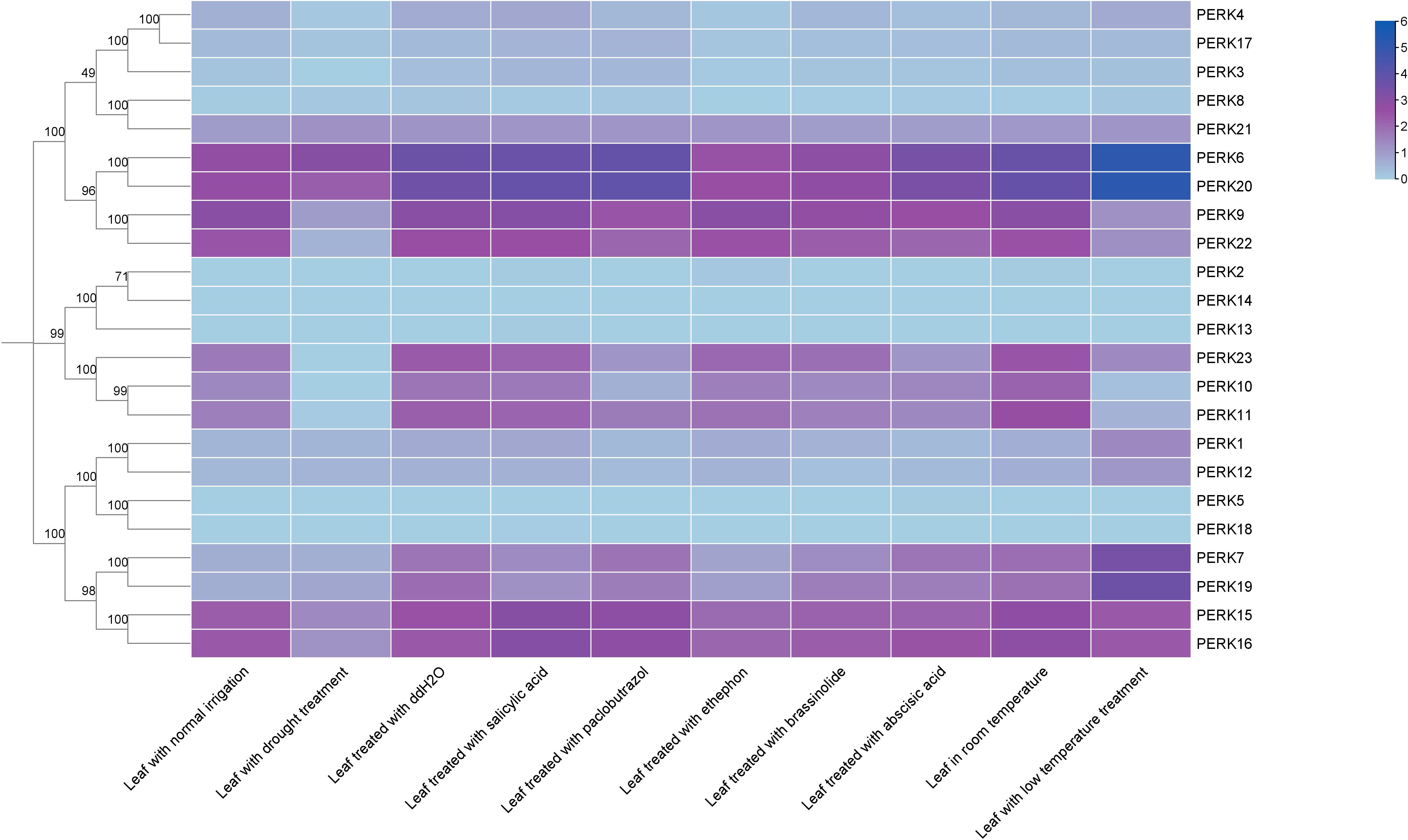

To elucidate the functional roles of peanut PERK genes under phytohormone application and abiotic stress conditions, the transcriptional responses of the 23 PERK genes were systematically analyzed following treatments with SA, ethephon, BR, ABA, paclobutrazol, as well as exposure to drought, ddH2O control, and low temperature.

Transcript abundance data for the 23 PERK genes are presented in Figure 6. Results showed that SA treatment significantly altered the expression of 2 genes (PERK8 and PERK19), defined as a fold change ≥ 2. Paclobutrazol treatment significantly altered the expression of 3 genes (PERK1, PERK10, and PERK23). Ethephon treatment induced significant changes in PERK3, PERK4, PERK6, PERK7, PERK17, PERK19, and PERK20 expression. BR treatment significantly altered the expression of 5 genes (PERK6, PERK8, PERK11, PERK12, and PERK20). Under ABA treatment, 6 genes (PERK1, PERK3, PERK4, PERK8, PERK11, and PERK23) exhibited significant expression level fluctuations. Drought stress significantly altered the expression of 9 genes (PERK4, PERK8, PERK9, PERK11, PERK15, PERK16, PERK17, PERK22, and PERK23), highlighting their important roles in drought response. In contrast, low temperature treatment significantly altered the expression of 12 genes: PERK1, PERK6, PERK7, PERK8, PERK9, PERK10, PERK11, PERK12, PERK19, PERK20, PERK22, and PERK23 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Expression patterns of peanut PERK genes in response to phytohormones and abiotic stresses. Heatmap analysis of log2(FPKM) values demonstrates transcriptional responsiveness to phytohormones and abiotic stresses.

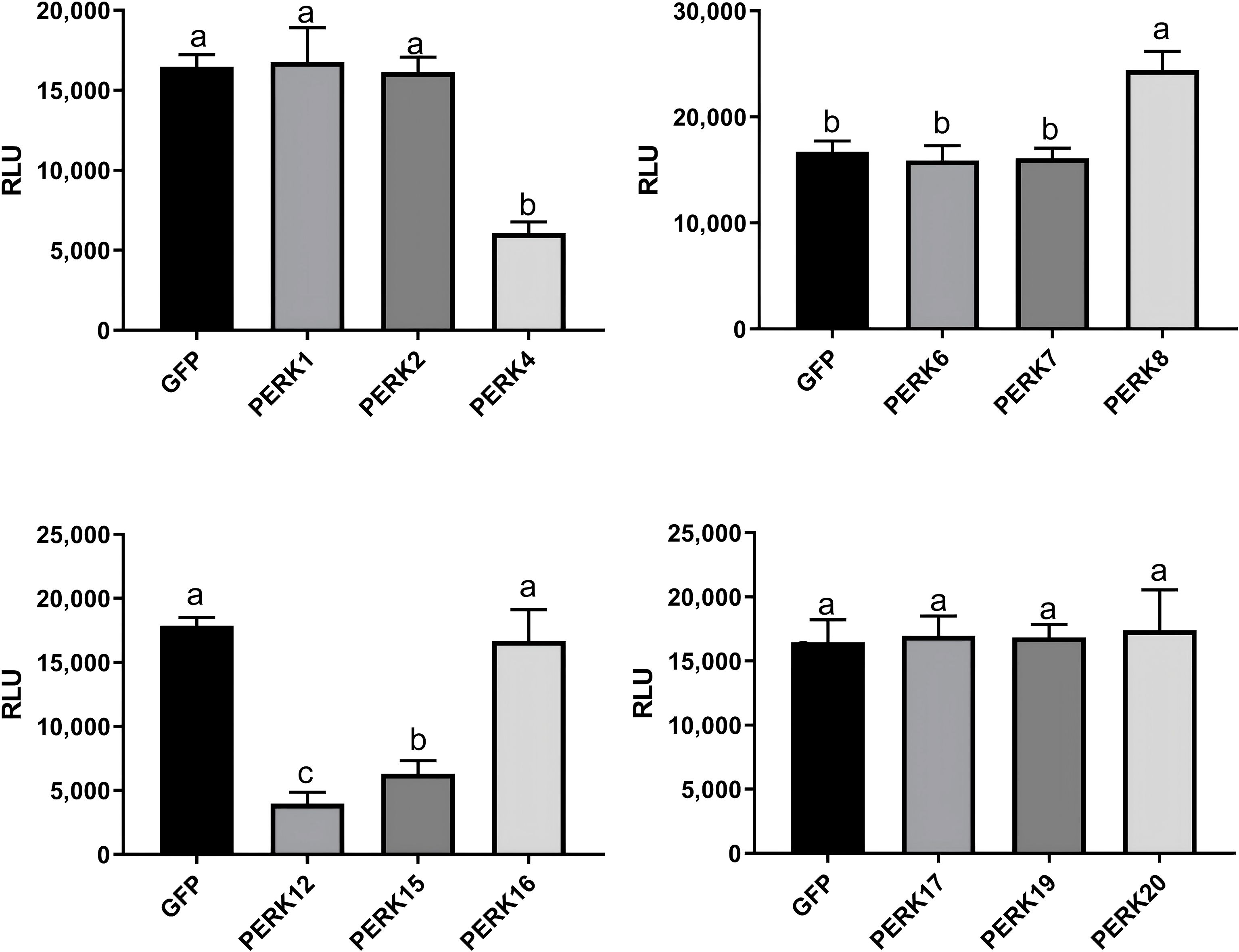

3.8 Analysis of PERK genes in flg22-induced ROS production

To further investigate the functional roles of PERK genes in plant immunity, 12 PERK family members were successfully cloned. Their regulatory activity in flg22-induced ROS production was assessed using a transient expression assay in N. benthamiana. We observed that the expression of 3 genes (PERK4, PERK12, PERK15) strongly suppressed flg22-induced ROS accumulation, while the expression of 1 gene (PERK8) strongly enhanced flg22-induced ROS burst (Figure 7). This functional divergence suggests distinct roles for these PERK members in either suppressing or enhancing plant basal immune responses during pathogen perception.

Figure 7. The Modulation of PAMP-triggered ROS by PERKs. The indicated constructs were transiently expressed by agrobacterium-mediated transient expression for 2 days and subjected to flg22-induced ROS examination (mean ± SD, n ≥ 8, and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test; different letters indicate significant difference at p < 0.01).

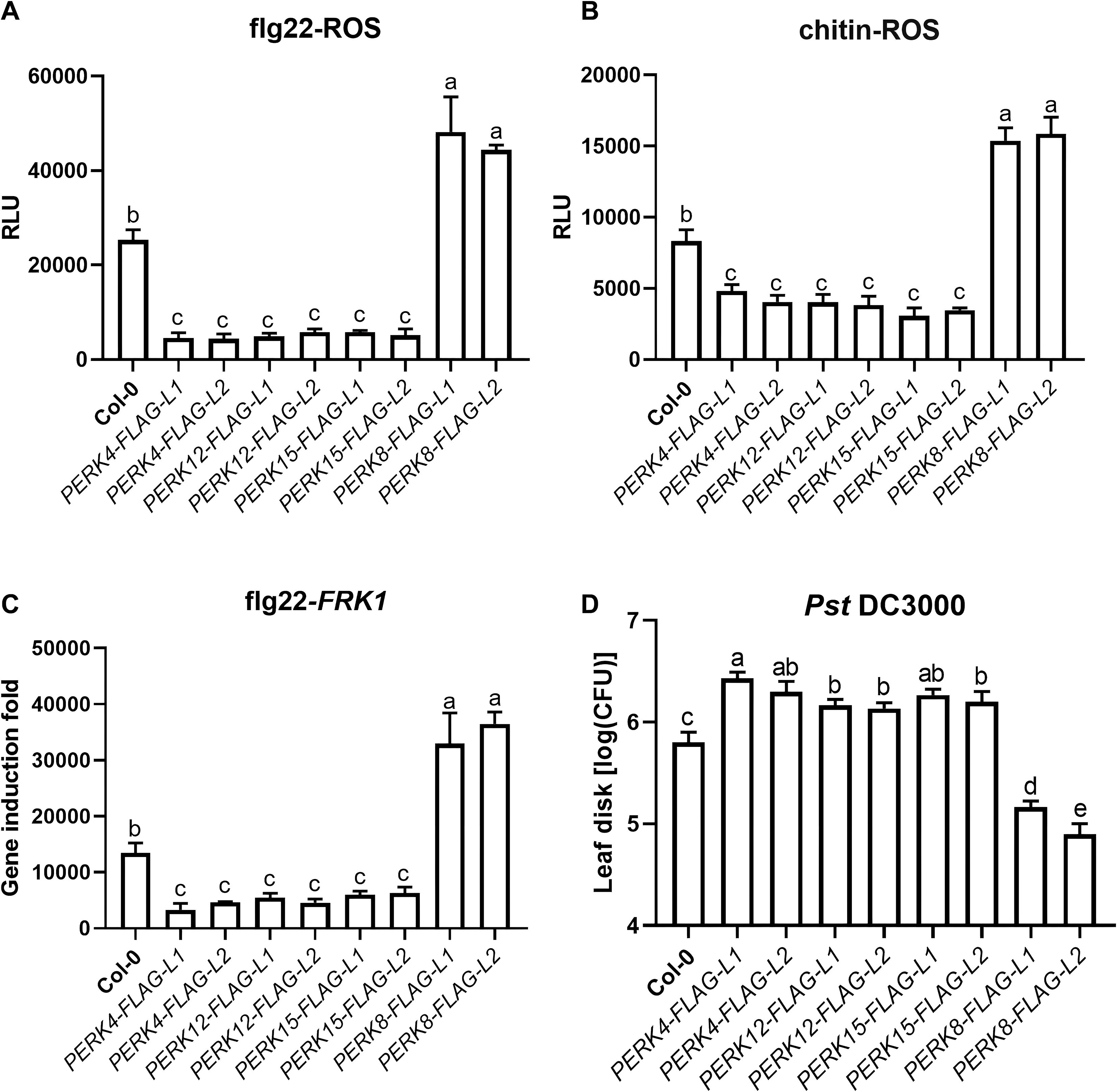

3.9 PERK proteins exhibit bidirectional regulatory roles in arabidopsis immunity

To further investigate the roles of PERK4, PERK12, PERK15, and PERK8 in plant immunity, we introduced PERK4-FLAG, PERK12-FLAG, PERK15-FLAG, and PERK8-FLAG into Arabidopsis via Agrobacterium-mediated stable transformation and obtained two independent transgenic lines for each construct: PERK4-FLAG-L1, PERK4-FLAG-L2, PERK12-FLAG-L1, PERK12-FLAG-L2, PERK15-FLAG-L1, PERK15-FLAG-L2, PERK8-FLAG-L1, and PERK8-FLAG-L2.

We subsequently examined PAMP-induced ROS production, PR gene expression, and resistance to Pst DC3000 in these transgenic lines. Our results showed that flg22-induced ROS burst was significantly damaged in the PERK4-, PERK12-, and PERK15-related transgenic plants compared to Col-0, whereas it was markedly enhanced in PERK8 transgenic lines. This indicates that stable expression of PERK4, PERK12, and PERK15 proteins significantly suppresses flg22-induced ROS burst, while stable expression of PERK8 enhances it (Figure 8A). We also detected chitin-induced ROS production in these transgenic lines, and the results were consistent with the trends observed for flg22-induced ROS burst (Figure 8B).

Figure 8. PERK proteins exhibit bidirectional regulatory roles in arabidopsis immunity. (A) flg22-induced ROS burst in leaves of Col-0 and the indicated PERK-FLAG transgenic lines. (B) chitin-induced ROS burst in the same set of plants as in (A). (C) Relative expression levels of the defense marker gene FRK1 in Col-0 and transgenic lines after flg22 treatment, measured by qRT-PCR. (D) Bacterial growth of Pst DC3000 in leaves of Col-0 and transgenic lines. Data represent mean ± SD from biologically independent replicates. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Consistent with these findings, we further observed that flg22-induced expression of FRK1, a commonly used defense marker gene, was significantly reduced in the PERK4-, PERK12-, and PERK15-related transgenic plants. In contrast, flg22-induced FRK1 expression was slightly enhanced in the PERK8-related transgenic lines (Figure 8C).

To assess the roles of PERKs in plant disease resistance, we challenged the transgenic plants with Pst DC3000. Compared with Col-0 plants, the PERK4-, PERK12-, and PERK15-related transgenic lines exhibited significantly enhanced susceptibility to Pst DC3000. Conversely, the PERK8-related transgenic plants showed markedly enhanced resistance to Pst DC3000 (Figure 8D).

Taken together, these results indicate that PERK4, PERK12, and PERK15 negatively regulate plant basal immune responses, whereas PERK8 acts as a positive regulator, revealing their bidirectional immune regulatory functions.

4 Discussion

This study provides the first systematic identification of 23 PERK gene family members within the peanut genome, coupled with a comprehensive analysis of their evolutionary characteristics, expression dynamics, and functional implications. As an important subfamily of RLKs, PERK genes are established as pivotal regulators of plant growth, development, and stress adaptation (Morris and Walker, 2003). We observed that the number of peanut PERK genes (23) is intermediate to that of A. thaliana (15) (Silva and Goring, 2002) and the allotetraploid cotton (33) (Qanmber et al., 2019), suggesting that the expansion of the PERK family in legumes correlates with genomic polyploidization levels. Notably, all identified peanut PERK genes contain introns (Figure 3B), contrasting sharply with the complete lack of introns reported for cotton GhPERK genes (Qanmber et al., 2019). This fundamental difference likely reflects distinct evolutionary trajectories and selective pressures. Variations in exon-intron structures typically arise from insertion/deletion events, and the consistent retention of introns in peanut PERKs suggests this family may occupy a relatively conserved evolutionary niche within legumes (Roy and Gilbert, 2005).

Phylogenetic classification grouped AhPERKs into three clades orthologous to those in Arabidopsis (Figure 2). Notably, Group II experienced a significant expansion in peanut, containing six members versus only one in Arabidopsis. This lineage-specific expansion hints at functional diversification or neofunctionalization in legumes, potentially linked to their unique biological traits like symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Supporting this, our promoter analysis revealed a rich repertoire of cis-elements associated with light response, ABA, and MeJA, underscoring the potential involvement of AhPERKs in integrating environmental and hormonal signals—a hallmark of RLK function (Invernizzi et al., 2022). These results align with the observed MeJA/ABA responsiveness of GhPERKs in cotton (Qanmber et al., 2019) and studies demonstrating AtPERK4-mediated ABA signaling in Arabidopsis (Bai et al., 2009a, b), supporting the conserved function of the PERK family in hormone regulation.

Tissue expression profiles indicated functional divergence among peanut PERK genes: 11 genes exhibited constitutive expression, while PERK2, PERK13, PERK14, and PERK18 displayed tissue-specific patterns (Figure 5). Of particular interest is the expression of PERK13/PERK14 exclusively in roots and root nodules, implying potential roles in the legume-specific symbiotic nitrogen fixation process. This strongly suggests a previously unexplored role for PERKs in the legume-specific symbiosis with rhizobia. Given that PERKs are hypothesized to sense cell wall dynamics (Borassi et al., 2016; Invernizzi et al., 2022), their expression in nodules—organs undergoing extensive cell wall remodeling—positions them as prime candidates for regulating infection thread development, symbiosome formation, or nodule organogenesis. This discovery opens a new avenue for research into how cell wall-associated receptors modulate symbiotic efficiency. Under abiotic stress conditions, 12 genes were significantly induced by low temperature and nine responded to drought stress (Figure 6). PERK1, PERK8, PERK11, and PERK23 were concurrently activated by both ABA and drought, consistent with the presence of predicted ABA-responsive elements in their promoters (Figure 4) and previous findings on PERK-mediated ABA signaling (Bai et al., 2009a).

The uneven chromosomal distribution of peanut PERK genes (Figure 1) may stem from local tandem duplication or chromosomal fragmentation events (Schauser et al., 2005), requiring validation via synteny analysis. Although gibberellin-responsive elements were predicted in promoters, GA-related data is absent from the phytohormone treatment experiments, necessitating supplementary validation. Future research should employ gene-editing technologies to generate PERK mutants for in-depth characterization of their molecular mechanisms in symbiotic nitrogen fixation (e.g., nodule development) and immune responses (e.g., ROS regulation).

Our study provides crucial functional insights into PERK-mediated immunity. While PERKs have been implicated in responses to pathogens and herbivores (Florentino et al., 2006; Invernizzi et al., 2022), their direct regulatory mechanisms in immune signaling remain opaque. Our functional assays using flg22-induced ROS burst as a readout for Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI) unveiled a bidirectional regulatory capacity among AhPERKs. Specifically, AhPERK4, AhPERK12, and AhPERK15 acted as negative regulators, suppressing ROS accumulation, defense gene expression, and resistance to Pseudomonas syringae. Conversely, AhPERK8 functioned as a positive regulator, enhancing these immune outputs. This divergence aligns with the emerging paradigm that RLK networks can finely tune immune responses through opposing actions (Zhou and Zhang, 2020). The negative regulation by some AhPERKs echoes the role of certain PERKs as negative modulators of growth processes like root elongation (Humphrey et al., 2015), suggesting a conserved function in signaling attenuation. The positive role of AhPERK8 finds a parallel in the wound-induced AtPERK1 (Silva and Goring, 2002), hinting at a potential conserved activation mechanism under different stresses. These results significantly advance current knowledge by moving beyond correlative expression studies to demonstrate direct and differential roles for PERK family members in modulating a key immune signaling pathway.

5 Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive genomic and functional characterization of the PERK gene family in peanut. We identified 23 AhPERK genes, revealing their non-uniform chromosomal distribution, conserved gene structures, and diversification into three phylogenetic subgroups. Promoter analysis indicated their potential involvement in diverse stress responses, which was corroborated by expression profiling showing that specific AhPERK members are differentially regulated by abiotic stresses and hormone treatments. Crucially, tissue-specific expression patterns suggest roles in both fundamental development and specialized root/nodule functions. The most significant finding is the functional divergence of AhPERK members in plant immunity. Functional validation demonstrated that AhPERK4, AhPERK12, and AhPERK15 act as negative regulators, while AhPERK8 acts as a positive regulator of basal immune responses, including PAMP-triggered ROS burst, defense gene expression, and resistance to bacterial pathogens. This reveals, for the first time in peanut, the bidirectional regulatory capacity of the PERK family in plant immunity. Collectively, our results establish a foundation for understanding the multifaceted roles of AhPERK genes, linking their structural features to expression dynamics and critical immune functions. These findings highlight specific AhPERK genes as promising candidates for further mechanistic studies and as potential genetic targets for enhancing stress resilience in legume crops.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

JP: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JY: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. DF: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. YS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. XZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. YC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. FX: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The research was supported by the Science Fund of the Jiangsu Vocational College of Agriculture and Forestry (2023kj16), Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (24KJA180003) and Zhenjiang Innovation Capacity Building Project (SS2024010).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1745895/full#supplementary-material

References

Altschul, S. F., Madden, T. L., Schäffer, A. A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., et al. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389

Bai, L., Zhang, G., Zhou, Y., Zhang, Z., Wang, W., Du, Y., et al. (2009b). Plasma membrane-associated proline-rich extensin-like receptor kinase 4, a novel regulator of Ca signalling, is required for abscisic acid responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 60, 314–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03956.x

Bai, L., Zhou, Y., and Song, C. P. (2009a). Arabidopsis proline-rich extensin-like receptor kinase 4 modulates the early event toward abscisic acid response in root tip growth. Plant Signaling behavior 2009a. 4, 1075–1077. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.11.9739

Bailey, T. L., Boden, M., Buske, F. A., Frith, M., Grant, C. E., Clementi, L., et al. (2009). MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335

Bauer, Z., Gómez-Gómez, L., Boller, T., and Felix, G. (2001). Sensitivity of different ecotypes and mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana toward the bacterial elicitor flagellin correlates with the presence of receptor-binding sites. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 45669–45676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102390200

Borassi, C., Sede, A. R., Mecchia, M. A., Salgado Salter, J. D., Marzol, E., Muschietti, J. P., et al. (2016). An update on cell surface proteins containing extensin-motifs. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 477–487. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv455

Champion, A., Kreis, M., Mockaitis, K., Picaud, A., and Henry, Y. (2004). Arabidopsis kinome: after the casting. Funct. Integr. Genomics. 4, 163–187. doi: 10.1007/s10142-003-0096-4

Chen, C. J., Chen, H., Zhang, Y., Thomas, H. R., Frank, M. H., He, Y. H., et al. (2020). TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant. 13, 1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009

Diévart, A. and Clark, S. E. (2004). LRR-containing receptors regulating plant development and defense. Development 131, 251–261. doi: 10.1242/dev.00998

Diévart, A., Dalal, M., Tax, F. E., Lacey, A. D., Huttly, A., Li, J., et al. (2003). CLAVATA1 dominant-negative alleles reveal functional overlap between multiple receptor kinases that regulate meristem and organ development. Plant Cell. 15, 1198–1211. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010504

Feng, P., Shi, J., Zhang, T., Zhong, Y., Zhang, L., Yu, G., et al. (2019). Zebra leaf 15, areceptor-like protein kinase involved in moderatelow temperature signaling pathway in rice. Rice. 12, 83. doi: 10.1186/s12284-019-0339-1

Florentino, L., Santos, A., Fontenelle, M., Pinheiro, G., Zerbini, F., Baracat-Pereira, M., et al. (2006). A PERK-like receptor kinase interacts with the geminivirus nuclear shuttle protein and potentiates viral infection. J. Virol. 80, 6648–6656. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00173-06

Huang, R., Xiao, D., Wang, X., Zhan, J., Wang, A., and He, L. (2022). Genome-wide identification, evolutionary and expression analyses of LEA gene family in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). BMC Plant Biol. 22, 155. doi: 10.1186/s12870-022-03462-7

Humphrey, T., Haasen, K., Aldea-Brydges, M., Sun, H., Zayed, Y., Indriolo, E., et al. (2015). PERK-KIPK-KCBP signalling negatively regulates root growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 71–83. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru390

Invernizzi, M., Hanemian, M., Keller, J., Libourel, C., and Roby, D. (2022). PERKing up our understanding of the proline-rich extensin-like receptor kinases, a forgotten plant receptor kinase family. New Phytologist. 235, 875–884. doi: 10.1111/nph.18166

Jiang, C. J., Li, X. L., Zou, J. X., Ren, J. Y., Jin, C. Y., Zhang, H., et al. (2021). Comparative transcriptome analysis of genes involved in the drought stress response of two peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) varieties. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 64. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02761-1

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C., and Tamura, K. (2018). MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096

Lescot, M., Déhais, P., Thijs, G., Marchal, K., Moreau, Y., van de Peer, Y., et al. (2002). PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325

Letunic, I. and Bork, P. (2018). 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D493–D496. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx922

Li, J. and Chory, J. (1997). A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell. 90, 929–938. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80357-8

Li, J., Wen, J., Lease, K. A., Doke, J. T., Tax, F. E., and Walker, J. C. (2002). BAK1, an Arabidopsis LRR receptor-like protein kinase, interacts with BRI1 and modulates brassinosteroid signaling. Cell. 110, 213–222. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00812-7

Morris, E. R. and Walker, J. C. (2003). Receptor-like protein kinases: the keys to response. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6, 339–342. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00055-4

Nakhamchik, A., Zhao, Z., Provart, N. J., Shiu, S. H., Keatley, S. K., Cameron, R. K., et al. (2004). A comprehensive expression analysis of the Arabidopsis proline-rich extensin-like receptor kinase gene family using bioinformatic and experimental approaches. Plant Cell Physiol. 45, 1875–1881. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch206

Nam, K. H. and Li, J. (2002). BRI1/BAK1, a receptor kinase pair mediating brassinosteroid signaling. Cell. 110, 203–212. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00814-0

Qanmber, G., Liu, J., Yu, D., Liu, Z., Lu, L., Mo, H., et al. (2019). Genome-wide identification and characterization of the perk gene family in Gossypium hirsutum reveals gene duplication and functional divergence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1750. doi: 10.3390/ijms20071750

Roy, S. W. and Gilbert, W. (2005). Complex early genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States America. 102, 1986–1991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408355101

Schauser, L., Wieloch, W., and Stougaard, J. (2005). Evolution of NIN-like proteins in Arabidopsis, rice, and. Lotus japonicus. J. Mol. Evol. 60, 229–237. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0144-2

Seijo, G., Lavia, G. I., Fernández, A., Krapovickas, A., Ducasse, D. A., Bertioli, D. J., et al. (2007). Genomic relationships between the cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea, Leguminosae) and its close relatives revealed by double GISH. Am. J. Bot. 94, 1963–1971. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.12.1963

Shiu, S. H. and Bleecker, A. B. (2001a). Receptor-like kinases from Arabidopsis form a monophyletic gene family related to animal receptor kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States America. 98, 10763–10768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181141598

Shiu, S. H. and Bleecker, A. B. (2001b). Plant receptor-like kinase gene family: diversity, function, and signaling. Science’s STKE. 113, re22. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1132001re22

Shiu, S. H. and Bleecker, A. B. (2003). Expansion of the receptor-like kinase/Pelle gene family and receptor-like proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 132, 530–543. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021964

Shiu, S. H., Karlowski, W. M., Pan, R. S., Tzeng, Y. H., Mayer, K. F. X., and Li, W. H. (2004). Comparative analysis of the receptor-like kinase family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Cell. 16, 1220–1234. doi: 10.1105/tpc.020834

Shpak, E. D., Berthiaume, C. T., Hill, E. J., and Torii, K. U. (2004). Synergistic interaction of three ERECTA-family receptor-like kinases controls Arabidopsis organ growth and flower development by promoting cell proliferation. Development. 131, 1491–1501. doi: 10.1242/dev.01028

Shpak, E. D., Lakeman, M. B., and Torii, K. U. (2003). Dominant-negative receptor uncovers redundancy in the Arabidopsis ERECTA Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase signaling pathway that regulates organ shape. Plant Cell. 15, 1095–1110. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010413

Silva, N. F. and Goring, D. R. (2002). The proline-rich, extensin-like receptor kinase-1 (PERK1) gene is rapidly induced by wounding. Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 667–685. doi: 10.1023/A:1019951120788

Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G., and Gibson, T. J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673

Xue, C., Li, W., Shen, R., and Lan, P. (2021). PERK13 modulates phosphate deficiency induced root hair elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 312, 111060. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2021.111060

Zhou, J. and Zhang, Y. (2020). Plant immunity: danger perception and signaling. Cell. 181, 978–989. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.028

Keywords: genestructure, genome-wide identification, PERK genes, phylogenetic analysis, plant innate immunity, tissue-specific expression

Citation: Peng J, Liu W, Yu J, Fu D, Sun Y, Zheng X, Chen Y, Xia F and Chen J (2026) Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of PERK genes in peanut and revelation of bidirectional immune regulatory function. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1745895. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1745895

Received: 13 November 2025; Accepted: 29 December 2025; Revised: 25 December 2025;

Published: 20 January 2026.

Edited by:

Cheng Song, West Anhui University, ChinaReviewed by:

Chinedu Charles Nwafor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, United StatesArvind Kumar Dubey, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, United States

Copyright © 2026 Peng, Liu, Yu, Fu, Sun, Zheng, Chen, Xia and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jiajia Chen, amlhamlhY2hlbkBqc2FmYy5lZHUuY24=

Jinfeng Peng1

Jinfeng Peng1 Xiangrong Zheng

Xiangrong Zheng Yuanyuan Chen

Yuanyuan Chen Jiajia Chen

Jiajia Chen