- 1Tropical Crops Genetic Resources Institute, State Key Laboratory of Tropical Crop Breeding, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, Haikou, Hainan, China

- 2Sanya Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, Sanya, Hainan, China

- 3Key Laboratory of Crop Gene Resources and Germplasm Enhancement in Southern China, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Haikou, China

- 4Key Laboratory of Tropical Crops Germplasm Resources Genetic Improvement and Innovation of Hainan Province, Haikou, China

- 5Rubber Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, Haikou, Hainan, China

SNP markers represent the most extensively distributed and abundant type of polymorphic markers. Although researchers have developed high-throughput detection methods for SNP markers, there remains a lack of simple, flexible, and cost-effective approaches for detecting small numbers of SNPs. To address this need, this study proposes a method for detecting SNPs based on T-C mismatch. Specifically, two upstream primers were designed with a single base difference at the 3’ end. Additionally, a T-C mismatch was introduced within 5 bp upstream of the 3’ end to distinguish SNPs. Detection was achieved through PCR amplification and subsequent gel electrophoresis analysis. In this study, twelve random SNPs from bitter gourd were selected, and the detection efficiency was found to be 83.3%. The proposed SNP detection method is characterized by its simplicity and flexibility, offering an effective tool for molecular marker-assisted selection breeding in applications such as stress resistance improvement and agricultural productivity enhancement.

Introduction

Molecular markers, discovered and applied since 1980s, such as random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) (Tingey and del Tufo, 1993), simple sequence repeat (SSR) (Zietkiewicz et al., 1994), sequence characterized amplified region (SCAR) (Deng et al., 1997), cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) (Konieczny and Ausubel, 1993), and amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) (Mueller and Wolfenbarger, 1999), played significant roles in marker assisted crop breeding and human disease diagnosis during the past few decades (Huang et al., 1992; Amiteye, 2021). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), including transition, transversion, insertion and deletion, employed as a new generation marker in marker assisted selection breeding in recent years. Compared to traditional molecular markers, SNPs are widely distributed in the genome about one SNP per approximately 1000 base pairs in human (Zhou et al., 2001; Koirala et al., 2011) and high throughput SNP detection platforms are available for SNP genotyping.

SNP represents the most prevalent form of genetic variation observed among individuals. The correlation between SNPs and an individual’s response to phenotypic variations, pathogens, and gene functions underscores the critical importance of rapid, sensitive, and reliable methods on SNP detection (Ganal et al., 2009). The detection of SNPs can be achieved through PCR or Sanger sequencing for low throughput, or via array-based detection techniques for high throughput. The field of SNP scoring has witnessed the development of a diverse array of techniques, each possessing distinct advantages and limitations. The Affymetrix arrays possess an exceptionally high probe density, allowing for the incorporation of millions of probes on a single chip. For instance, the Affymetrix Human SNP Array 6.0 encompasses probes targeting 906,600 SNPs (Kanthaswamy et al., 2013). The Illumina Infinium whole-genome genotyping (WGG) technology utilizes a primer extension reaction to assay SNPs, which can be combined with high-density BeadChips to create array platforms capable of genotyping over 1,000,000 SNPs per slide (Gunderson, 2009; Adler et al., 2013). KASP is an allele-specific oligo extension-based PCR assay that utilizes fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) for the detection of genetic variations, such as SNPs and insertions/deletions (InDels), in 96-, 384-, and 1,536-well microtiter plate formats (He et al., 2014).

It could be argued that no single SNP genotyping platform is sufficiently comprehensive to cater to all objectives, the inclusion of certain low-throughput detection methods is also imperative. A multiplex SNP detection system utilizing thin-film optical biosensor silicon chips, arrayed with aldehyde-labeled oligonucleotides and hybridized with PCR amplicons in the presence of a mixture of biotinylated detector probes, exhibits high sensitivity and specificity through color changes on the chip surface (Zhong et al., 2003; Bai et al., 2007). However, the immobilization of nucleotides onto the chip entails significant costs. Another SNP detection approach is based on specific primer extension reactions coupled with PPi detection, and this method has successfully employed DNA primers that contain mismatched bases in the vicinity of their 3’-termini to diminish false positive signals in selective primer extension reactions (Zhou et al., 2001). Nevertheless, this method is technically complex and requires a high level of expertise. A more convenient single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection method, developed by introducing an artificial mismatched base pair into the forward primer and implemented via PCR coupled with agarose gel electrophoresis, has also proven effective (Chen and Schedl, 2021). Although this approach offers operational simplicity, it does not determine which specific base pair configuration yields optimal amplification efficiency. Therefore, there remains a need for a convenient, flexible, effective, and cost-efficient SNP detection method suitable for routine laboratory applications.

Constitutive Photomorphogenic 1 (COP1) and Elongated Hypocotyl 5 (HY5) are master regulatory hub in plants, central not just to light signaling but also to integrating a wide array of stress responses (Chattopadhyay et al., 1998; Lau and Deng, 2012; Han et al., 2020, Xiao et al., 2021, Mankotia et al., 2024). To facilitate the identification of the mutants cop1–6 and hy5-215, we developed a simplified method as an alternative to Sanger sequencing. In this study we found the substitution of the base T with C within a 5 bp region upstream of the SNP significantly enhances primer specificity. In brief, we constructed a simple and low throughput SNP detection system via adding artificial mismatch bases to the forward primer, and this approach is a flexible, rapid, sensitive, and inexpensive way for low throughput SNP scoring.

Materials and methods

The Arabidopsis thaliana wild-type plants utilized in this investigation were of the Columbia ecotype (Col), the Arabidopsis mutant of cop1-6 (McNellis et al., 1994) are in Col background. The seeds were surface-sterilized by immersion in a 10% NaClO solution for 10 minutes and subsequently rinsed with sterile distilled ddH2O four times. Following this, the seeds were stored in darkness at a temperature of 4 °C for a period of four days. Subsequently, they were plated on MS medium (4.4 g/L MS, 1% sucrose, 0.8% agar, pH5.8) and transferred to light chambers maintained at a temperature of 22 °C under an intensity of 20,000 lux. Once germinated, the seedlings were transplanted into small pots and cultivated in a greenhouse maintained at 22 °C with a light intensity of 20,000 lux, under long-day photoperiod conditions (16 h light/8 h dark). The leaves of bitter gourd were supported by the Institute of Tropical Crop Genetic Resources in Hainan province, China. The seeds were wrapped in a moist cloth and incubated at 37 °C under dark conditions until germination occurred. Following germination, which typically took 2–3 days, the sprouted seeds were transplanted into small pots on February 15th of 2023. These pots were then placed inside a greenhouse with temperatures ranging from 25 to 28 °C and light intensity of approximately 20,000 lux. The seedlings remained in the greenhouse until they developed 4–6 true leaves. Subsequently, the seedlings were transferred to an open field where they were sown directly into the soil.

The plant DNA was extracted using the Universal Genomic DNA Kit (CWBIO, CW2298M). Primers were designed with a melting temperature (Tm) ranging from 55 to 62 °C and a length of 20–25 base pairs. PCR was performed using the 2×Hieff®PCR Master Mix with Dye (Yeasen, 10102ES50). For PCR reaction system (20 ul), about 1 ul (100 ng) DNA, 1 ul primers (F+R, 10 uM/L), 10 ul 2×Hieff®PCR Master Mix, 8 ul ddH2O. All PCR used the cycling program: initial denature at 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of denature at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s; final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The products were loaded onto a 1% agarose gel and subjected to electrophoresis at a constant voltage of 150 V for 15 minutes following completion of the PCR program.

Result

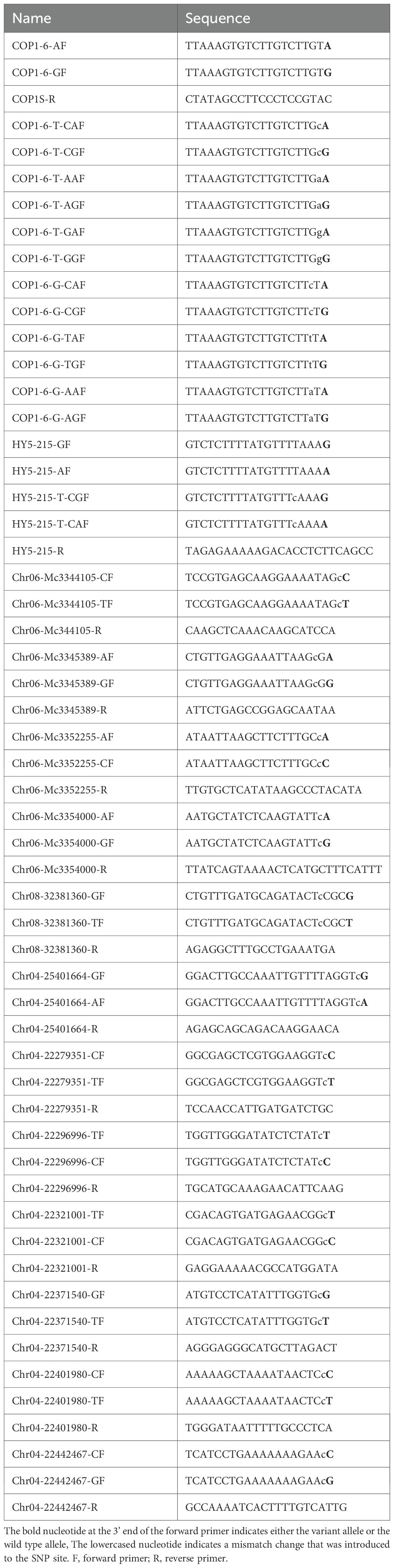

The COP1 gene serves as an essential prototypical negative regulator of photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana (Lau and Deng, 2012; Han et al., 2020), and the mutant cop1–6 allele possesses a point mutation (A-G) at the 3’ end of intron 4, which results in a 15-bp insertion due to cryptic splicing (Ang and Deng, 1994). To distinguish the cop1–6 mutant from the wild type (WT), SNP detection is employed to identify the point mutation, with PCR amplification followed by agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE) serving as an efficient method. First, forward and reverse primers were designed, noting that two forward primers differing by 1 bp at the 3’ end were used for the cop1–6 mutant (COP1-6GF) and WT (COP1-6AF). Second, after PCR amplification, products were analyzed using AGE. Ideally, COP1-6AF/COP1-6SR should amplify only WT, while COP1-6GF/COP1-6SR should amplify only the cop1–6 mutant. However, both primer pairs amplified both WT and the mutant (Figure 1A). To address this issue, a 1 bp mismatch was introduced by replacing the nucleotide T adjacent to the 3’ end with C. The gel image demonstrated that the ‘T-C’ substitution effectively discriminated between the cop1–6 mutant and WT (Figure 1B). When T was replaced with A, only the COP1-6-T-AGF/COP1-6SR primer pair produced visible PCR products (Figure 1C), whereas no PCR products were detected with COP1-6-T-GGF/COP1-6SR or COP1-6-T-GAF/COP1-6SR (Figure 1D). Additionally, introducing a 1 bp mismatch by replacing the nucleotide G next to the 3’ end did not yield any PCR products (data not shown). These experiments indicate that introducing a ‘T-C’ mismatch at the 3’ end of the forward primer is effective for SNP detection.

Figure 1. Detection the point mutation between Col and cop1-6. Using the DNA of Col and cop1–6 as template respectively, PCR reactions were performed using the following primer pairs: COP1-6AF/COP1-6SR (upper) and COP1-6GF/COP1-6SR (lower) (A), COP1-6-T-CAF/COP1-6SR (upper) and COP1-6-T-CGF/COP1-6SR (lower) (B), COP1-6-T-AAF/COP1-6SR (upper) and COP1-6-T-AGF/COP1-6SR (lower) (C), COP1-6-T-GAF/COP1-6SR (upper) and COP1-6-T-GGF/COP1-6SR (lower) (D). These reactions were carried out at varying annealing temperatures (55 °C, 55.7 °C, 57 °C, and 59 °C). Subsequently, the PCR products were analyzed via agarose gel electrophoresis.

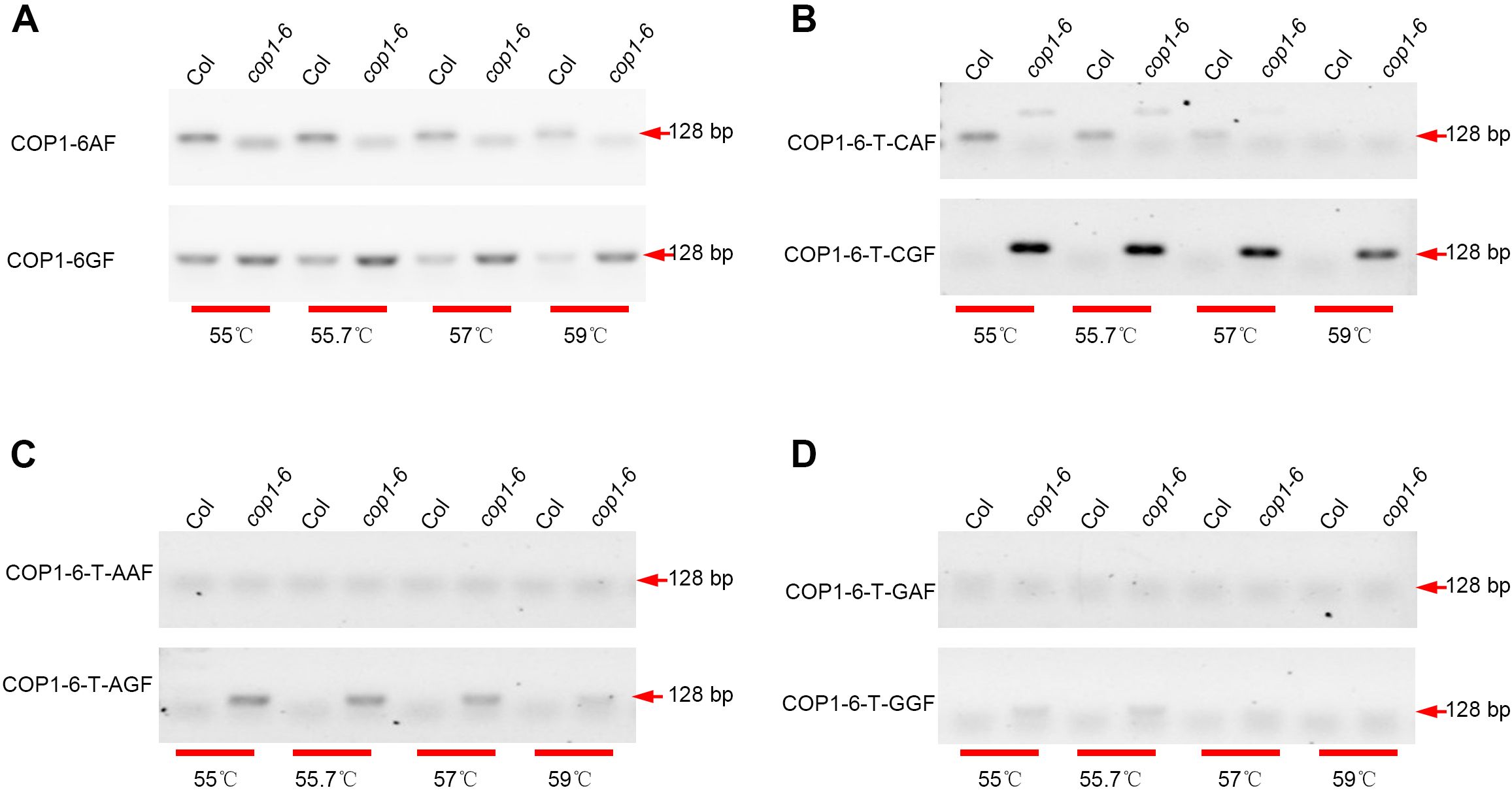

Elongated Hypocotyl 5 (HY5) (Chattopadhyay et al., 1998) serves as a positive regulator in the photomorphogenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. The hy5–215 mutant harbors a point mutation (G-A) within the first intron. To differentiate the hy5–215 mutant from the WT, we designed a reverse primer and two forward primers: HY5-215-GF/HY5-215-R for WT, and HY5-215-AF/HY5-215-R for hy5-215. AGE analysis revealed that the primer pair HY5-215-GF/HY5-215-R could distinguish the hy5–215 mutant at an annealing temperature of 57 °C, while HY5-215-AF/HY5-215-R could identify the WT at 55 °C annealing (Figure 2A). To further enhance discrimination, we introduced a 1-bp mismatch (‘T-C’) adjacent to the 3’ end of the forward primer. As anticipated, the modified primer pairs HY5-215-T-CGF/HY5-215-R and HY5-215-T-CAF/HY5-215-R successfully discriminated between the hy5–215 mutant and WT at 57 °C annealing (Figure 2B). These findings confirm that a ‘T-C’ mismatch at the 3’ end of the forward primer is effective for single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection.

Figure 2. Detection the point mutation between Col and hy5-215. PCR reactions were conducted using DNA templates from Col and hy5-215, with the following primer pairs employed: HY5-215-GF/HY5-215-R (upper) and HY5-215-AF/HY5-215-R (lower) (A), HY5-215-T-CGF/HY5-215-R (upper) and HY5-215-T-CAF/HY5-215-R (lower) (B). These reactions were carried out at varying annealing temperatures (55 °C, 55.7 °C, 57 °C, and 59 °C). Subsequently, the PCR products were analyzed via agarose gel electrophoresis.

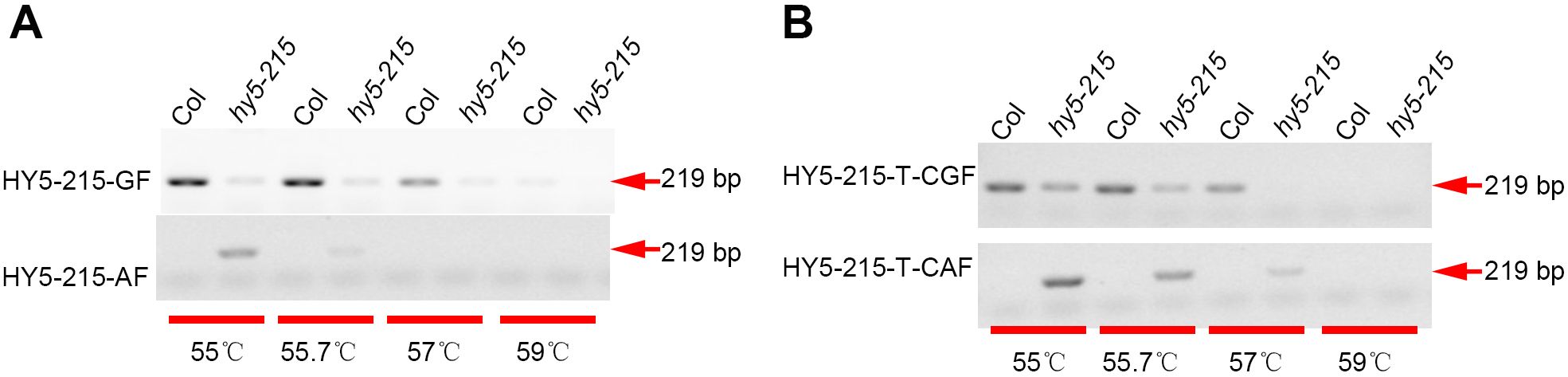

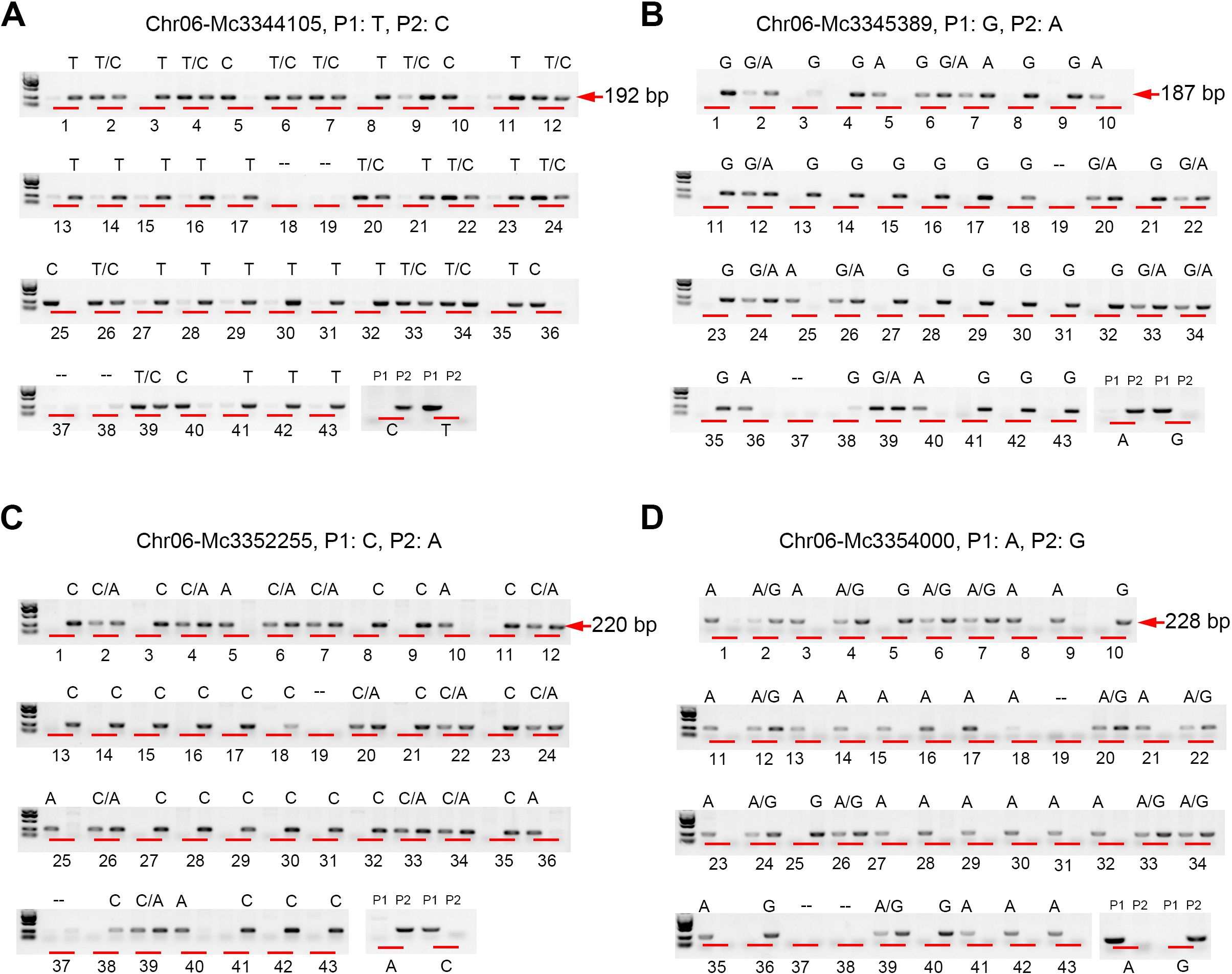

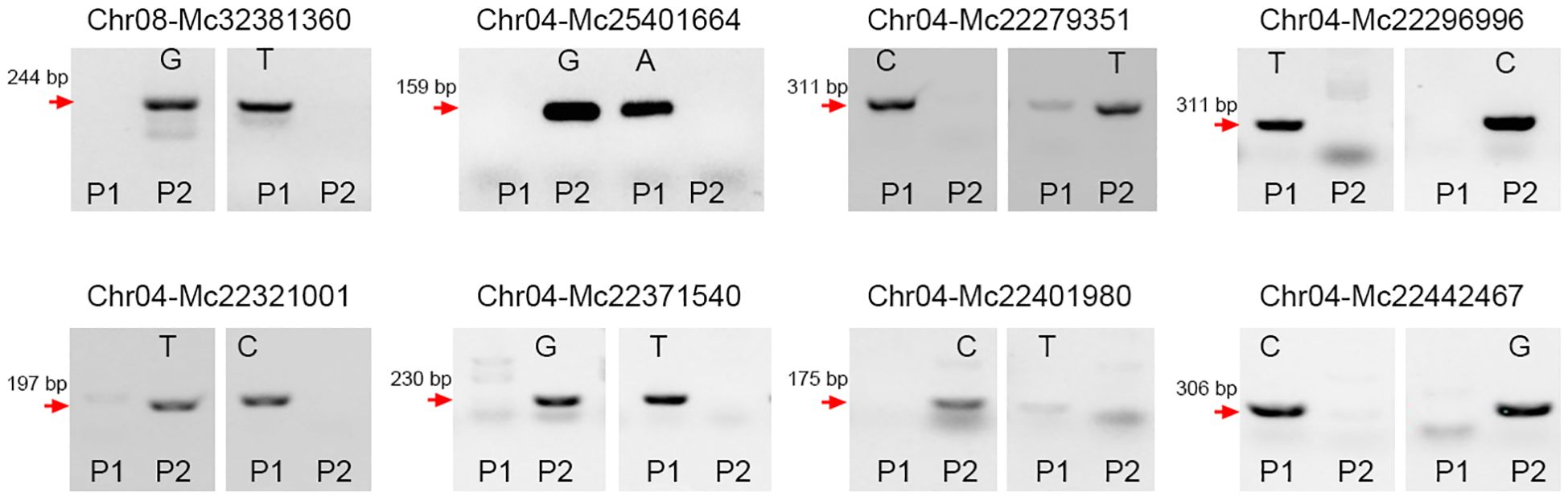

To expand the application of the SNP detection method, we designed SNP molecular markers for genotyping in bitter gourd (Momordica charantia). Fruit length is one of the most important agronomic traits for bitter gourd. Using bulked segregation analysis (BSA), the confidence interval for this trait was localized to chromosome 6 between 909,395 bp and 5,047,012 bp. We selected four candidate SNPs at positions 3,344,105 (C/T), 3,345,389 (A/G), 3,352,255 (A/C), and 3,354,000 (A/G) to evaluate their association with fruit length. By introducing a 1-bp mismatch (‘T-C’) in the forward primers (Table 1), we successfully detected these four SNP markers. Furthermore, we validated the effectiveness of this method by genotyping F2 populations (Figures 3A–D), which confirmed its reliability. Additionally, we employed this method to identify an additional eight SNPs in bitter gourd, specifically: Chr08-Mc32381360 (G/T), Chr04-Mc25401664 (G/A), Chr04-Mc22279351 (C/T), Chr04-Mc22296996 (T/C), Chr04-Mc22321001 (T/C), Chr04-Mc22371540 (G/T), Chr04-Mc22401980 (C/T), and Chr04-Mc22442467 (C/G) (Figure 4). With the exception of Chr04-Mc22279351 (C/T) and Chr04-Mc22401980 (C/T), the detection of the other six SNPs performed exceptionally well. For Mc22279351, the primer with a terminal base pair “T” does not clearly distinguish between P1 (gray value: 4510.53) and P2 (16145.90). For Mc22401980, the primer with a terminal base pair “T” exhibits very low amplification efficiency.

Figure 3. The (‘T-C’) mismatched method was utilized to design SNP markers for detecting the F2 generations of bitter gourd. A 1-bp mismatch (‘T-C’) was introduced into the forward primers to detect SNPs at positions Chr06 3,344,105 (A), 3,345,389 (B), 3,352,255 (C), and 3,354,000 (D) in bitter gourd. Here, P1 and P2 denote the parental lines, while “–” indicates the absence of PCR products. These reactions were carried out at an annealing temperature of 55 °C. Subsequently, the PCR products were analyzed via agarose gel electrophoresis.

Figure 4. Using the (‘T-C’) mismatched method to design SNP markers in bitter gourd. Eight SNP markers, including Chr08-Mc32381360 (G/T), Chr04-Mc25401664 (G/A), Chr04-Mc22279351 (C/T), Chr04-Mc22296996 (T/C), Chr04-Mc22321001 (T/C), Chr04-Mc22371540 (G/T), Chr04-Mc22401980 (C/T), and Chr04-Mc22442467 (C/G), were developed. P1 and P2 represent two parental lines. These reactions were carried out at an annealing temperature of 55 °C. Subsequently, the PCR products were analyzed via agarose gel electrophoresis.

Discussion

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a highly sensitive and versatile tool widely used in both research and clinical settings for genotyping and the detection of naturally occurring or experimentally induced genetic variations. However, the identification of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) by PCR remains challenging due to the minimal difference between variant and wild-type alleles—often a single nucleotide substitution. Conventional approaches such as Sanger sequencing and commercial detection kits are typically time-consuming for large-scale SNP analysis. The strategic incorporation of mismatched bases into primer design enables SNP discrimination through PCR amplification followed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Nevertheless, the lack of a standardized protocol for introducing such mismatches presents significant challenges in developing reliable primer sets, often requiring extensive optimization that entails considerable time, labor, and financial resources. This limitation has hindered the broader application of this otherwise promising method. To explore and establish a universal primer design strategy based on targeted base mismatches, a series of primers were developed and evaluated across multiple studies for detecting the cop1–6 mutant in Arabidopsis thaliana, thereby validating the method’s broad applicability. During genetic screening experiments aimed at distinguishing the wild type from the cop1–6 mutant, we observed that substitutions of A, G, or C within 2–3 base pairs upstream of the 3′ end of the forward primer resulted in unstable amplification outcomes, including failed amplification or non-specific amplification of both alleles. Stable and specific discrimination was achieved only when T was substituted with C, generating an A–C mismatch. Substitutions with A or G at this position led to reduced amplification efficiency or inadequate differentiation between genotypes. This optimized approach represents a significant improvement over existing methods, such as those employing mismatches at the −2 position without specifying the most effective mismatching base pair (Chen and Schedl, 2021).

In this study, difficulties were encountered in designing primers to discriminate the wild-type negative regulator AtDET1 and its mutant det1-1 (G/A) (Pepper and Chory, 1997), as well as the SNP locus Chr04-Mc22357388 (C/T) in bitter gourd. The inability to clearly differentiate the det1–1 mutant from the wild type in Arabidopsis thaliana is likely attributable to the excessively high GC content (74%) in the forward primer. In contrast, the GC content at the corresponding region of the bitter gourd SNP site Chr04-Mc22357388 (C/T) was only 16%, which falls outside the optimal range. Across this study, 14 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were successfully identified, and the GC content of the designed forward primers ranged from 21% to 63%. To ensure optimal primer design for comprehensive SNP detection, it is recommended that the GC content of forward primers fall within the range of 21% to 63%. In conclusion, the SNP detection strategy described in this study is not only facile and time-efficient but also exhibits remarkable flexibility and cost-effectiveness, offering practical advantages for routine genotyping applications.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

RY: Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. JL:Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology, Investigation. NY: Writing – review & editing, Resources. XH: Validation, Writing – review & editing. XW: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. YY: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32460760) and the Project of National Key Laboratory for Tropical Crop Breeding (SKLTCBZRJJ202503, NKLTCBCXTD35), the Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (ZDYF2024XDNY183), and Hainan Province Winter Vegetable Industry Technology System (HNARS-05-G02, HNARS-05-SX).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adler, A. J., Wiley, G. B., and Gaffney, P. M. (2013). Infinium assay for large-scale SNP genotyping applications. J. visualized experiments 19, e50683. doi: 10.3791/50683

Amiteye, S. (2021). Basic concepts and methodologies of DNA marker systems in plant molecular breeding. Heliyon 7, e08093. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08093

Ang, L. H. and Deng, X. W. (1994). Regulatory hierarchy of photomorphogenic loci: allele-specific and light-dependent interaction between the HY5 and COP1 loci. Plant Cell 6, 613–628. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.5.613

Bai, S. L., Zhong, X., Ma, L., Zheng, W., Fan, L. M., Wei, N., et al. (2007). A simple and reliable assay for detecting specific nucleotide sequences in plants using optical thin-film biosensor chips. Plant J. 49, 354–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02951.x

Chattopadhyay, S., Ang, L. H., Puente, P., Deng, X. W., and Wei, N. (1998). Arabidopsis bZIP protein HY5 directly interacts with light-responsive promoters in mediating light control of gene expression. Plant Cell 10, 673–683. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.5.673

Chen, J. and Schedl, T. (2021). A simple one-step PCR assay for SNP detection. microPublication Biol. 2021. doi: 10.17912/micropub.biology.000399

Deng, Z., Xiao, S., Huang, S., and Gmitter, F. G., Jr. (1997). Development and characterization of SCAR markers linked to the citrus tristeza virus resistance gene from Poncirus trifoliata. Genome 40, 697–704. doi: 10.1139/g97-792

Ganal, M. W., Altmann, T., and Röder, M. S. (2009). SNP identification in crop plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12, 211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.12.009

Gunderson, K. L. (2009). Whole-genome genotyping on bead arrays. Methods Mol. Biol. (Clifton N.J.) 529, 197–213. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-538-1_13

Han, X., Huang, X., and Deng, X. W. (2020). The photomorphogenic central repressor COP1: conservation and functional diversification during evolution. Plant Commun. 1, 100044. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2020.100044

He, C., Holme, J., and Anthony, J. (2014). SNP genotyping: the KASP assay. Methods Mol. Biol. (Clifton N.J.) 1145, 75–86. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0446-4_7

Huang, M. M., Arnheim, N., and Goodman, M. F. (1992). Extension of base mispairs by Taq DNA polymerase: implications for single nucleotide discrimination in PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 4567–4573. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.17.4567

Kanthaswamy, S., Ng, J., Ross, C. T., Trask, J. S., Smith, D. G., Buffalo, V. S., et al. (2013). Identifying human-rhesus macaque gene orthologs using heterospecific SNP probes. Genomics 101, 30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.09.001

Koirala, D., Yu, Z., Dhakal, S., and Mao, H. (2011). Detection of single nucleotide polymorphism using tension-dependent stochastic behavior of a single-molecule template. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 9988–9991. doi: 10.1021/ja201976r

Konieczny, A. and Ausubel, F. M. (1993). A procedure for mapping Arabidopsis mutations using co-dominant ecotype-specific PCR-based markers. Plant J. 4, 403–410. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1993.04020403.x

Lau, O. S. and Deng, X. W. (2012). The photomorphogenic repressors COP1 and DET1: 20 years later. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 584–593. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.05.004

Mankotia, S., Jakhar, P., and Satbhai, S. B. (2024). HY5: a key regulator for light-mediated nutrient uptake and utilization by plants. New Phytol. 241, 1929–1935. doi: 10.1111/nph.19516

McNellis, T. W., von Arnim, A. G., Araki, T., Komeda, Y., Miséra, S., and Deng, X. W. (1994). Genetic and molecular analysis of an allelic series of cop1 mutants suggests functional roles for the multiple protein domains. Plant Cell 6, 487–500. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.4.487

Mueller, U. G. and Wolfenbarger, L. L. (1999). AFLP genotyping and fingerprinting. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14, 389–394. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01659-6

Pepper, A. E. and Chory, J. (1997). Extragenic suppressors of the Arabidopsis det1 mutant identify elements of flowering-time and light-response regulatory pathways. Genetics 145, 1125–1137. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.4.1125

Tingey, S. V. and del Tufo, J. P. (1993). Genetic analysis with random amplified polymorphic DNA markers. Plant Physiol. 101, 349–352. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.2.349

Xiao, Y., Chu, L., Zhang, Y., Bian, Y., Xiao, J., and Xu, D. (2021). HY5: A pivotal regulator of light-dependent development in higher plants. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.800989

Zhong, X. B., Reynolds, R., Kidd, J. R., Kidd, K. K., Jenison, R., Marlar, R. A., et al. (2003). Single-nucleotide polymorphism genotyping on optical thin-film biosensor chips. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States America 100, 11559–11564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934783100

Zhou, G., Kamahori, M., Okano, K., Chuan, G., Harada, K., and Kambara, H. (2001). Quantitative detection of single nucleotide polymorphisms for a pooled sample by a bioluminometric assay coupled with modified primer extension reactions (BAMPER). Nucleic Acids Res. 29, E93. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.19.e93

Keywords: detection methods, forward primer, mismatch, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), stress resistance

Citation: Yu R, Liu J, Niu Y, Han X, Wang X and Yang Y (2025) A simple and flexible approach for detecting small numbers of SNPs. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1748099. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1748099

Received: 17 November 2025; Accepted: 05 December 2025; Revised: 03 December 2025;

Published: 19 December 2025.

Edited by:

Ruirui Huang, University of San Francisco, United StatesReviewed by:

Wang Rui, Sichuan University, ChinaYuanbao Li, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, China

Copyright © 2025 Yu, Liu, Niu, Han, Wang and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Renbo Yu, eXVyZW5ibzYxMkAxNjMuY29t; Xiaoyi Wang, bWlja3lfeGlhb0AxNjMuY29t; Yan Yang, eWFueWFuZ0BjYXRhcy5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Renbo Yu

Renbo Yu Jie Liu1†

Jie Liu1† Yu Niu

Yu Niu Xu Han

Xu Han Xiaoyi Wang

Xiaoyi Wang