- 1Department of Biochemistry, Chaudhary Charan Singh (CCS) Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar, Haryana, India

- 2Indian Council of Agriculture Research (ICAR)- Central Soil Salinity Research Institute, Karnal, Haryana, India

- 3Department of Seed Science & Technology, Chaudhary Charan Singh (CCS) Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar, Haryana, India

- 4Department of Agronomy, Chaudhary Charan Singh (CCS) Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar, Haryana, India

- 5Division of Research and Innovation, Uttaranchal University, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India

- 6School of Agriculture and the Environment, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand

The miracle tree, M. oleifera, is valued for its nutritional composition, climate adaptability, industrial and environmental usefulness. Despite well-known benefits, nutritional composition varies with the geographical location. The seeds of Moringa are rich in high-quality oil and protein and are also a source of carbohydrates, but their relative quantities vary among geographical locations. A meta-regression analysis was carried out using PRISMA guidelines, to explore the variability, and deciding factors in Moringa seeds. A systematic search of Scopus and google Scholar identified reports that mentioned morphological or nutritional or both traits was carried out. After removing duplicates and reviews, total 31 original research articles were included in the study. Two independent datasets, morphological and nutritional, were prepared by extracting numerical data of mature seeds. Statistical framework included Pearson’s correlation to quantify trait relationship and ANCOVA to assess covariate effects on nutritional components. Datasets were analyzed using R software. Random effect meta regression model was employed to assess the heterogeneity in nutrient composition across climatic zones. The crude fat, total carbohydrates and crude protein were highly variable (σ = 14.56, 14.54 and 12.08 respectively). The variabilities in ash and moisture were low (σ =1.41 and 2.48 respectively) while crude fiber showed intermediate variability (σ = 2.87). Although, there was a trend in nutritional composition of M. oleifera seeds along the latitude and climatic zones, statistical model fitting was non-significant for these variables. Pearson’s correlation among nutritional components was pronounced and significant, supported by carbon-nitrogen metabolism. This study did not find any trend in the highly variable morphological components (CV 38.52% and 43.12% for length and width respectively) of Moringa seeds with geographical location.

1 Introduction

Moringa (Moringa oleifera), often referred to as the “miracle tree,” is of significant importance owing to its exceptional nutritional and medicinal properties. This fast-growing plant is native to parts of Africa and Asia, and has gained global recognition for its multifaceted benefits. Moringa leaves, seeds, and pods are rich in essential vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, making them a valuable source of nutrition, particularly in regions facing food insecurity (Gopalkrishnan et al., 2016; Pandey et al., 2019; Rai et al., 2023). The plant’s medicinal properties have been utilized in traditional medicine for centuries, with potential applications in treating various ailments, including inflammation, diabetes, and cardiovascular issues. Additionally, moringa’s industrial potential, ability to purify water, and its use as a sustainable crop for both human consumption and livestock feed further underscore its importance in addressing global challenges related to nutrition, health, and environmental sustainability (Mulugeta and Fekadu, 2014).

In the past decade, moringa has gained the attention of researchers and they are trying to explore the medicinal, agricultural, environmental, and industrial potential of the crop. Like other parts of the plant, moringa seeds are a rich source of nutrients. These are particularly considered a good source of high-quality oil and protein. Moringa seed oil is extensively used in cosmetic industry, has the potential to be used as edible cooking oil and can be used to produce biodiesel. Moringa seed proteins are unique in their ability purify water. But high variations in moringa seed oil and protein content are evident from the scientific research. Banerji and Bajpai (2009) reported that oil content of moringa seeds from 20 clones of India was higher than the oil content reported from Pakistan, Malaysia and Kenya. Other crops such as soyabean and barley also exhibit differences in nutrient composition of seeds when grown in different environmental conditions (Bellaloui et al., 2016; Xue et al., 2016). According to Rani et al. (2025), environmental conditions play important role in determining quality of moringa seeds. An analysis of variation in nutritional composition of seeds across various agroclimatic regions could help make informed decision on the sourcing of seeds for particular application.

While, influence of location is evident, none of the study comprehensively covers worldwide locations. The current data on seed morphology and nutritional composition of moringa seeds is highly fragmented and variable with individual studies reporting inconsistent estimates due to differences in geographical origin, climatic conditions, genotypes, and analytical methodologies. Meta-analysis is essential in this study to integrate widely scattered data, generate more precise estimates of trait variability, and evaluate the influence of geographical and climatic factors on Moringa seed quality, which cannot be achieved through individual studies alone.

Apart from variations in basic nutritional components, various secondary metabolites also accumulate differentially. Accumulation of phenols, tannins, flavonoids, terpenes, etc. is higher in adverse environmental conditions (Qaderi et al., 2023). Environmental stressors act as stimuli that change gene expression pattern and therefor alter biochemical pathways. Secondary metabolites being protective in nature, accumulate to enhance plant adaptability to stresses and alter the quality of seed. Secondary metabolites are derived from primary metabolites. Studying variations in proximate values of primary metabolites will provide a stepping stone in further investigations of these specialized compounds.

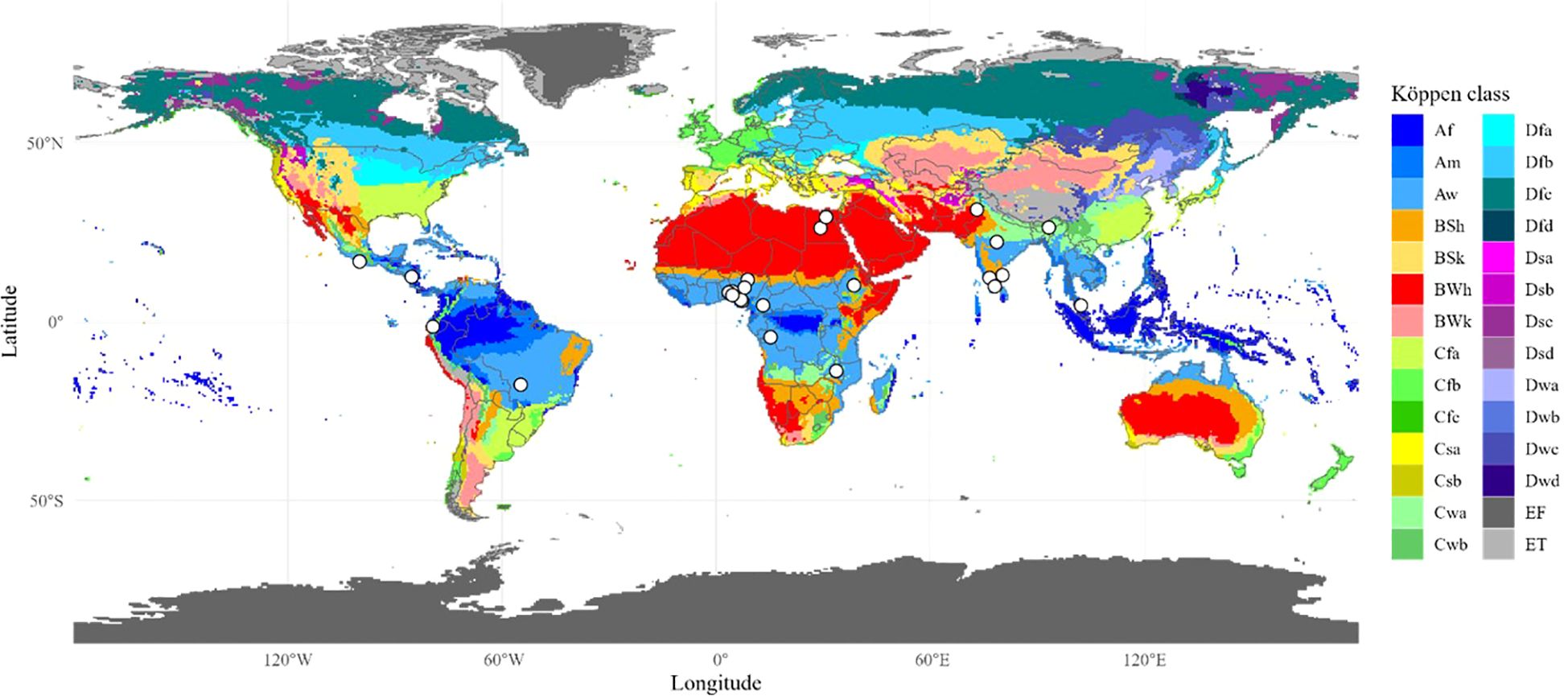

This study covers locations across globe which were not uniformly dispersed but concentrated near equator in tropical and subtropical zone. There were no reports from temperate region. Moreover, the weather conditions, seasons and accurate location of sampling were not uniformly presented in the selected reports, which may be critical in determining the quality of seeds. Therefore, by considering approximate coordinates, we presented a broader view of trends and correlations in various traits. The purpose of this study is to explore the factors affecting morphological variability and nutritional composition of moringa seeds across various agroclimatic regions through meta-analytic approach.

2 Materials and methods

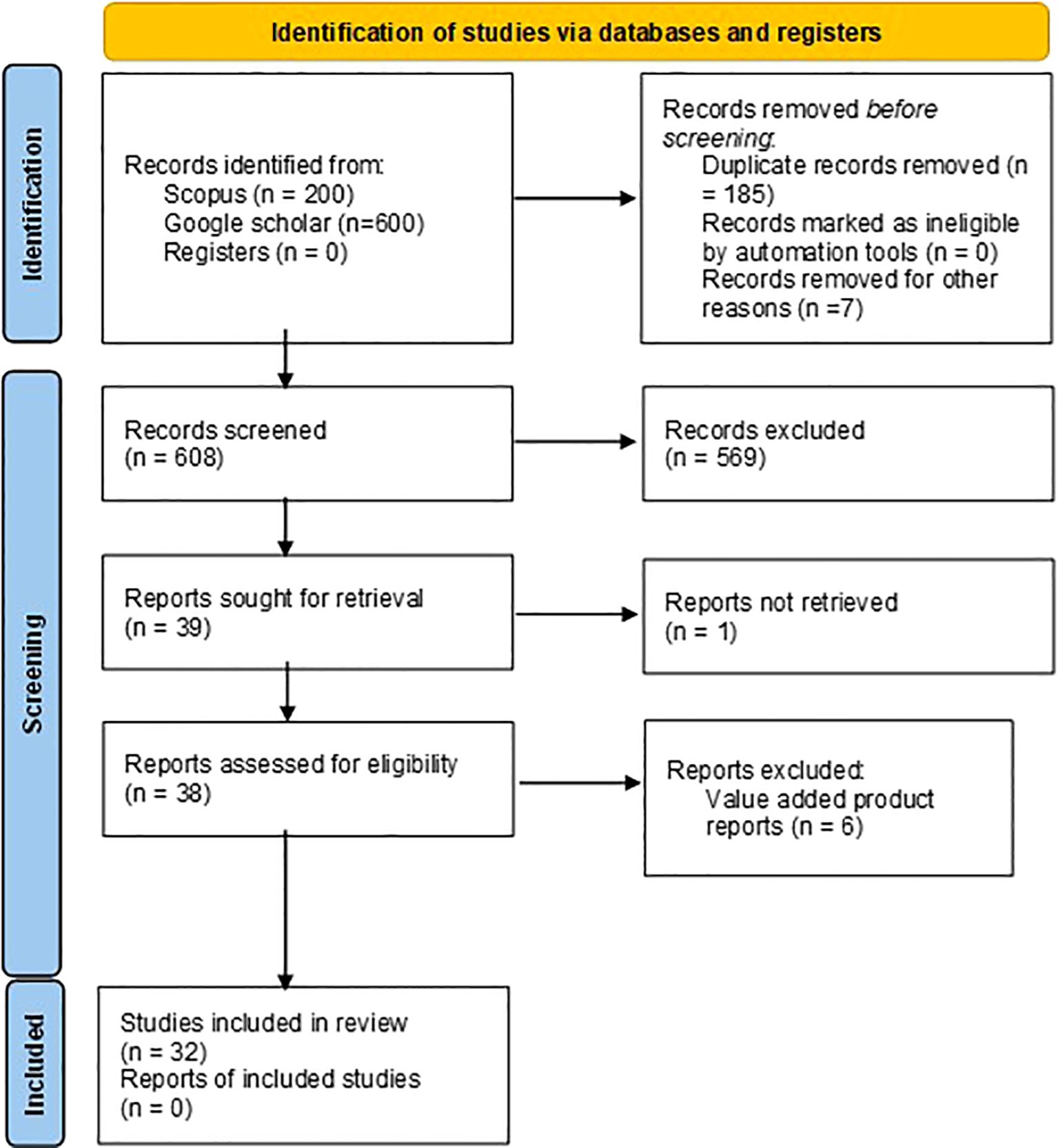

The keywords “Moringa oleifera seed morphology”, “Moringa oleifera seed proximate composition” and “Moringa oleifera seed nutritional composition” were used to search relevant research articles in Scopus database and Google Scholar. A total of 200 studies were identified with the relevant keywords in the title and abstract in Scopus. Publish or perish software was used to extract top 200 studied from google scholar for each keyword search. A total of 600 studies were extracted from Google scholar. All the 800 studies were imported in Zotero reference manager and 185 duplicated were removed. 3 irrelevant erratum and 4 conference abstracts were removed. 608 articles were screened manually for morphological and nutritional composition related work on raw moringa seeds and total 569 article were excluded. 39 articles sought for retrieval where 1 article was not retrieved. 38 reports were assessed for eligibility and 7 found ineligible because raw seed morphological or nutritional data or was not found in the articles (nutritional data of value-added product was given). A total of 31 studies included in the review. The study selection process is summarized in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Figure 1). Required data was extracted and two datasets were prepared: morphological and nutritional composition.

The analysis was performed irrespective of the age (full mature fresh, full mature dry or non-mature) of the seeds. Only datasets of moringa seeds grown without any stressor or treatment were selected. Numerical data for morphological and nutritional traits were directly extracted from tables and figures presented in the included studies using a predefined extraction sheet. Because extraction involved only objective quantitative values rather than subjective interpretation or coding, inter-rater reliability measures were not applicable. Data accuracy was ensured through independent cross-checking of all entries by a second reviewer.

The locations were geocoded utilizing tidygeocoder package in R, which uses the OpenStreetMap Nominatim API (Cambon et al., 2021). Where exact location was not known, geocoding returned the centroid of the nearest identifiable administrative region.

Koppen-Geiger climate map (Beck et al., 2023) was loaded as a raster in R (Lemenkova, 2020) with a resolution of 0.5° and geocoded locations were spatially overlaid on this raster to extract the corresponding climatic zone and generate the climatic map (Figure 2). Broad climatic zones were assigned to the study locations.

Figure 2. Koppen-Geiger climate zones with study locations. Koppen-Geiger climate map is widely accepted. The white dots indicate study locations. These dots were visually inspected for the respective climatic zone. Full names of abbreviated climatic zones are provided in supplementary file.

2.1 Morphological characteristics of M. oleifera seeds

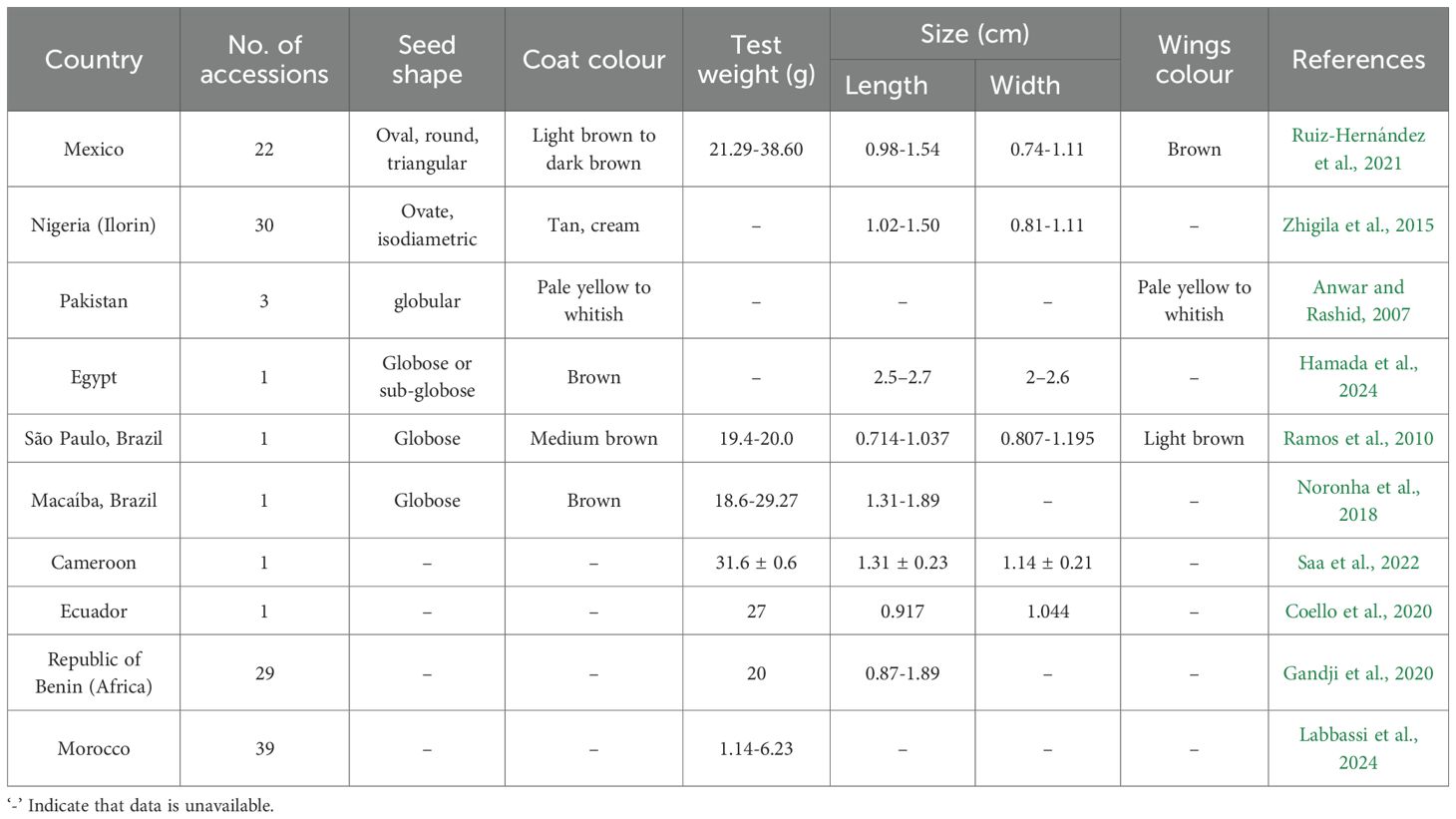

A total of eight studies covering 59 accessions of 9 countries were selected to compare moringa seeds for morphological characteristics (Table 1). The seed shape, color, test weight, length, width, and wing color characteristics were considered. Data is harmonized by unit conversion to gram for test weight and centimeter for length and width. Based on the data, a qualitative estimate of the seed shape, seed color, and wing color parameters was performed manually. A lack of quantitative data pertaining to these traits in the selected studies restricted the quantitative estimate. The statistical analysis of the quantitative traits (weight, length and width) was then performed.

2.2 Nutritional composition of M. oleifera seeds

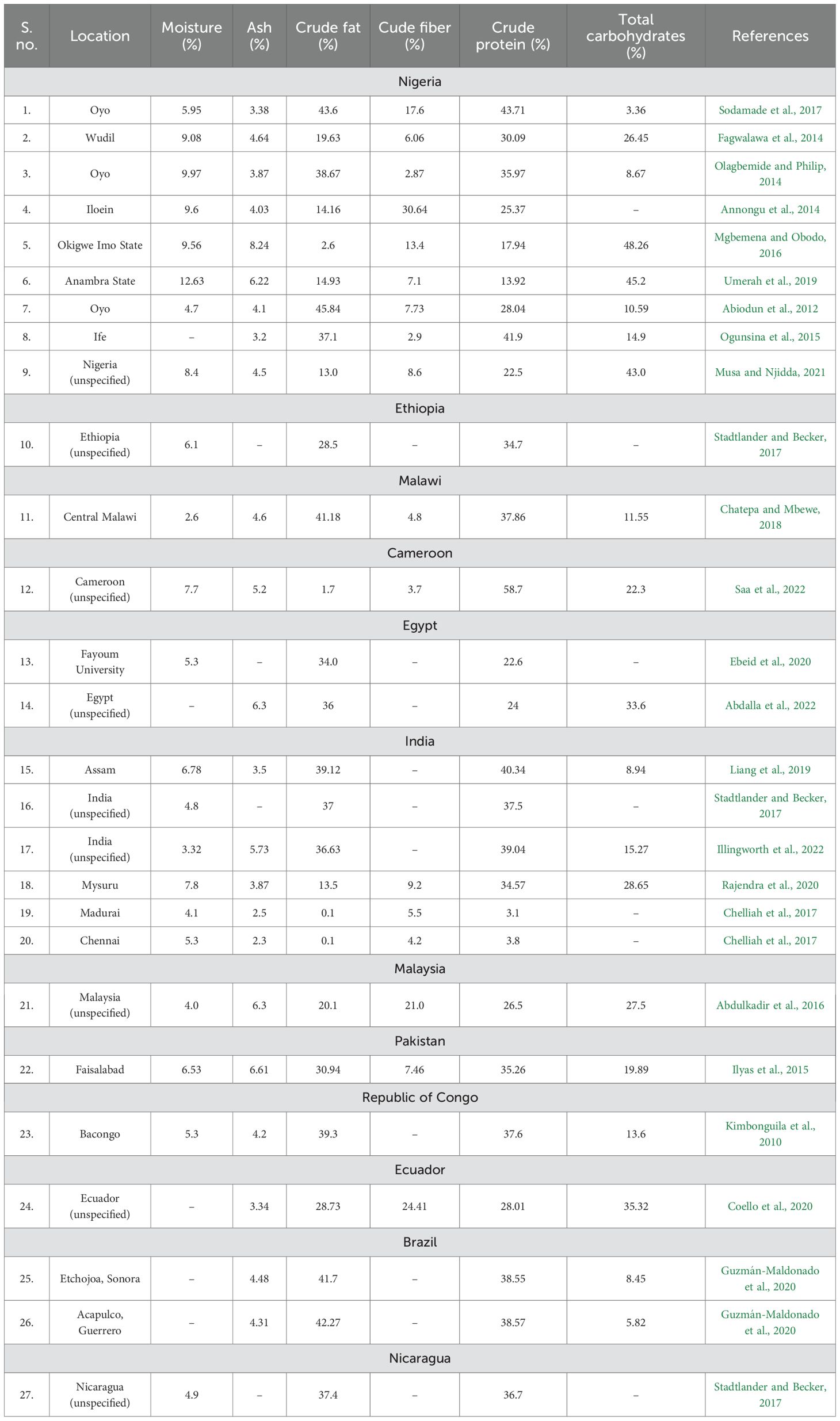

A total of 23 studies covering 12 countries with 27 locations were selected for the study of proximate composition (Table 2). Data is harmonized by conversion to percentage values. Data was statistically analyzed to study variations, nutrient correlation, correlation with distance from the equator, and climatic zone.

3 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R 4.5.0 software in Rstudio (posit). The missing data in both datasets were handled using multiple imputation (m=5) with the mice package in R, employing predictive mean matching (PMM). This method was chosen because it maintains the variability and distribution of numeric variables while allowing robust downstream statistical analyses like correlation and meta-regression (van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011). The variables used in the imputation model were seed morphological traits (weight, length and width) and compositional traits (ash, moisture, crude fat, crude protein, crude fiber and total carbohydrates). Convergence diagnostics were not explicitly plotted, but the imputation process was performed under default monitoring and inspected for consistency of generated values.

Multiple imputation was employed to handle missing morphological data for getting trait correlation only. Because the dataset we retrieved was so small and incomplete to draw any correlation without imputation. Other analyses were performed without imputation to eliminate chances of any bias that may arise in small datasets because of PMM. The correlation between variable components was computed using Pearson’s method to identify interacting traits.

4 Results

4.1 Morphological characteristics of M. oleifera seeds

In view of the wide distribution of moringa across the globe, it is expected to have variability. The moringa seeds are globose or oval in shape. These bear a tan to brown colored seed coat with three equidistant peppery wings, which are usually brittle and cream to light brown in color.

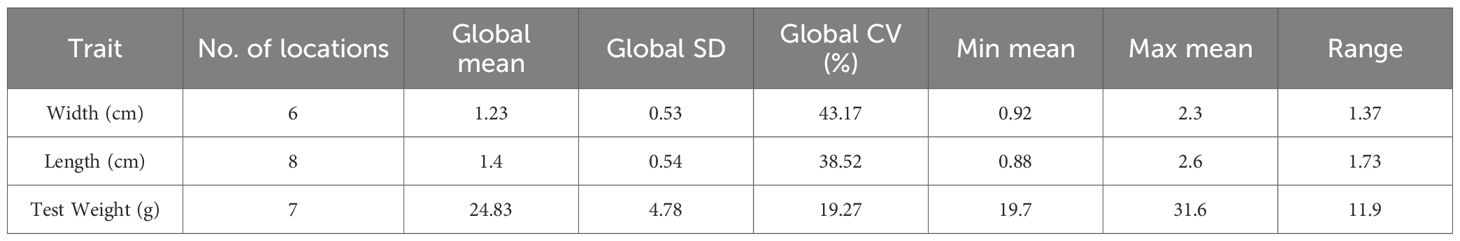

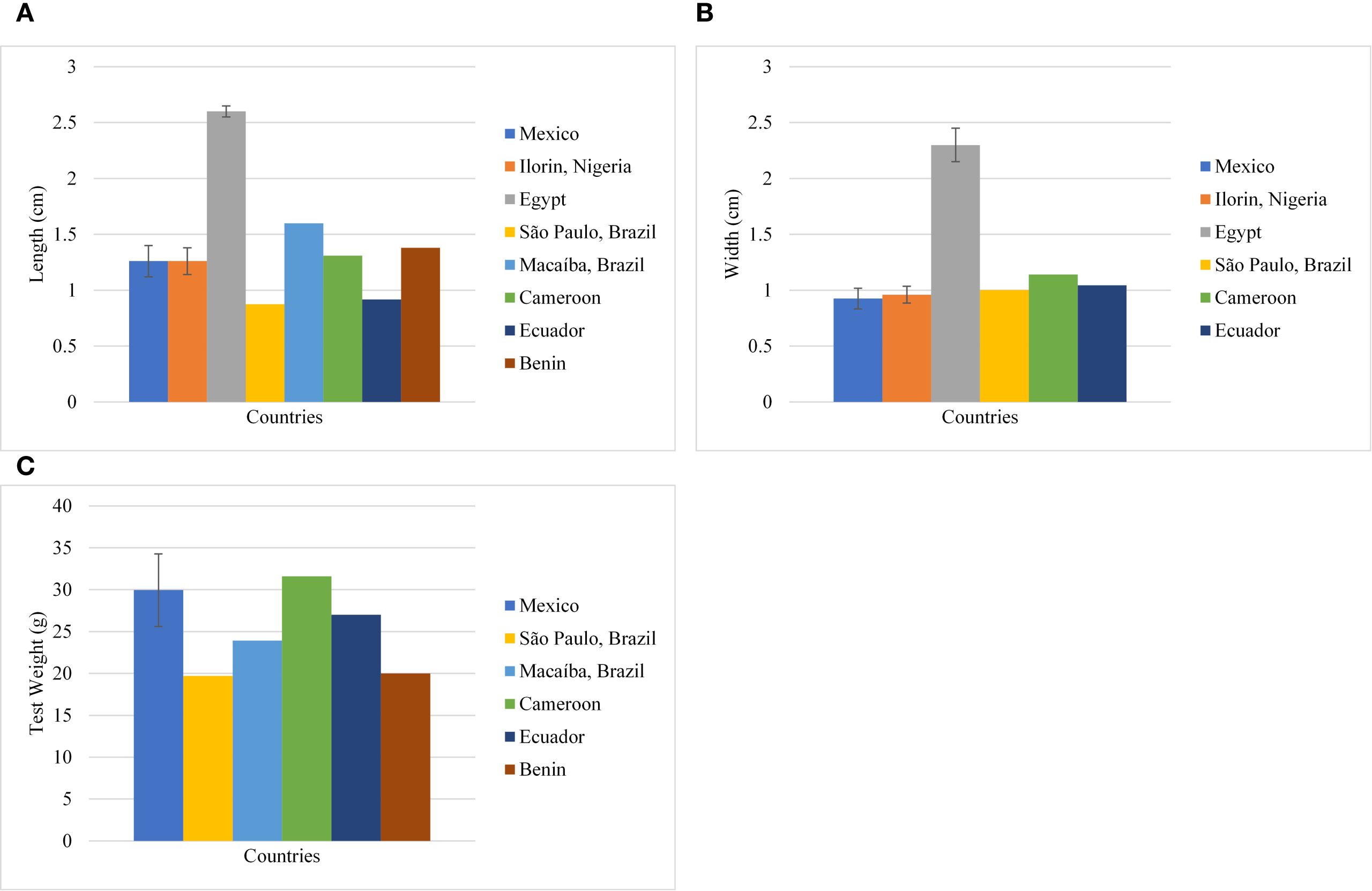

With the limited data available to date, the variability in length, width, and test weight of seeds was calculated. Test weight with coefficient of variance (CV) 19.27%, was moderately variable while seed length and width were highly variable with CV 38.52% and 43.12% respectively (Table 3; Figure 3). The seed size index, roundness, and elongation were calculated with the available dimensions, and a quantitative measure of the shape was obtained. The quantitative measure predicted a spherical and elliptical shape (Table 4), which is in agreement with the qualitative measure in Table 1.

Figure 3. Variability (Mean ± SD) of morphological traits in M. oleifera seeds with location. (A) seed length (cm) (B) width (cm); (C) Test weight.

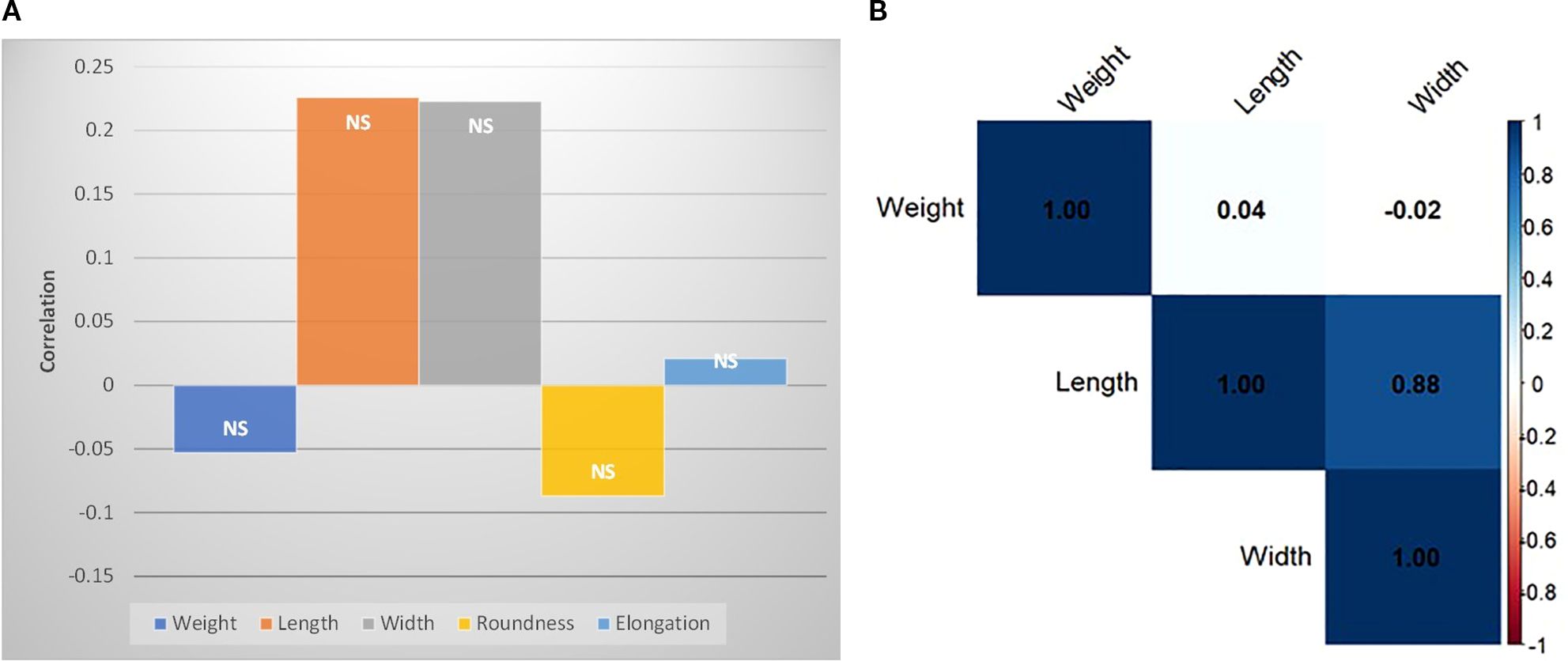

The correlation of the morphological traits (length, width, weight, elongation and roundness) with absolute distance from the equator is statistically non-significant (Figure 4A). Although a very high positive correlation (p-value= 0.0008) was found between length and width (Figure 4B). Surprisingly, there was no correlation of these traits with test weight.

Figure 4. Pearson’s correlation of M. oleifera seed morphological traits (A) with distance from equator, (B) among weight, length and width.

4.2 Nutritional composition of M. oleifera seeds

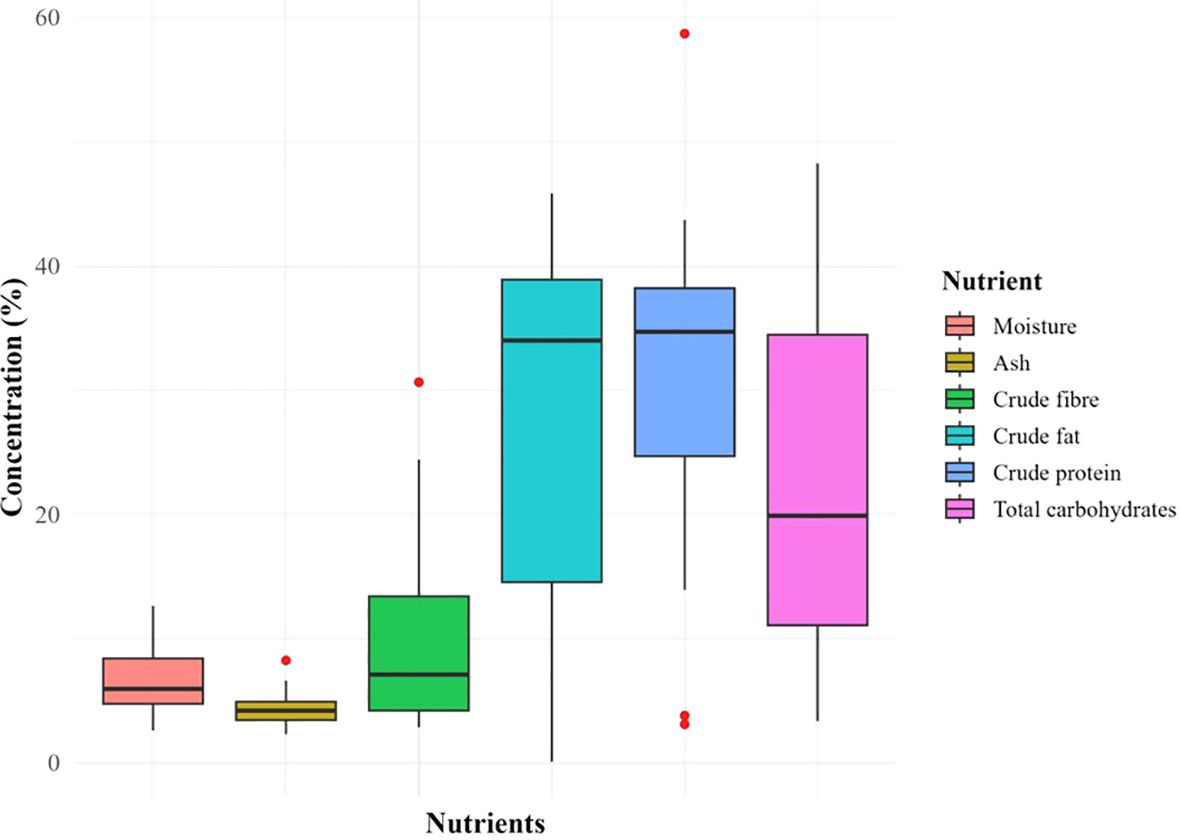

In the selected scientific literature, most of the researchers removed hull while seed processing before biochemical analysis. Therefore, the data presented here is for dehulled seeds. Boxplots in Figure 5 represents central tendency and variability in the nutrient composition of the seeds. The crude fat, total carbohydrates and crude protein were present in abundance with high variability (σ = 14.56, 14.54 and 12.08 respectively) across the globe. Ash and moisture were least abundant and least variable (σ =1.41 and 2.48 respectively) while crude fiber showed intermediate variability (σ = 2.87) as well as abundance. The crude fat showed highest range among the parameters. Some outliers present the possibility of further widening of the range as research progresses and more data is available (Supplementary File 2).

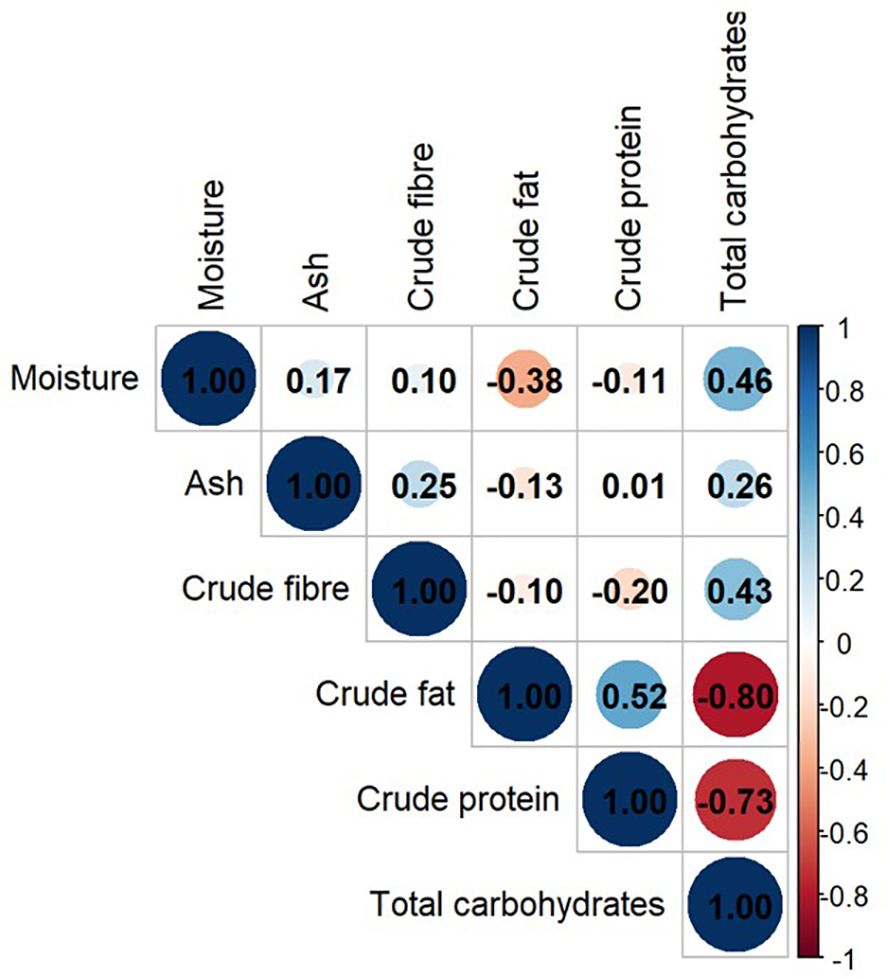

4.3 Correlation among nutrients in M. oleifera seeds

In the Pearson’s correlation matrix, total carbohydrates correlated with most nutritional components. It had a correlation with crude fat (r-value = -0.80 and p-value = 0), crude protein (r = -0.73, p-value = 0), crude fiber (r = 0.43, p-value = 0.026) and moisture (r = 0.46, p-value = 0.016) as shown in Figure 6. Crude fat and crude protein were moderately positively correlated (r = 0.52, p-value = 0.005). The crude fat and protein had little or no correlation with other nutritional components (Figure 6, Supplementary File 3).

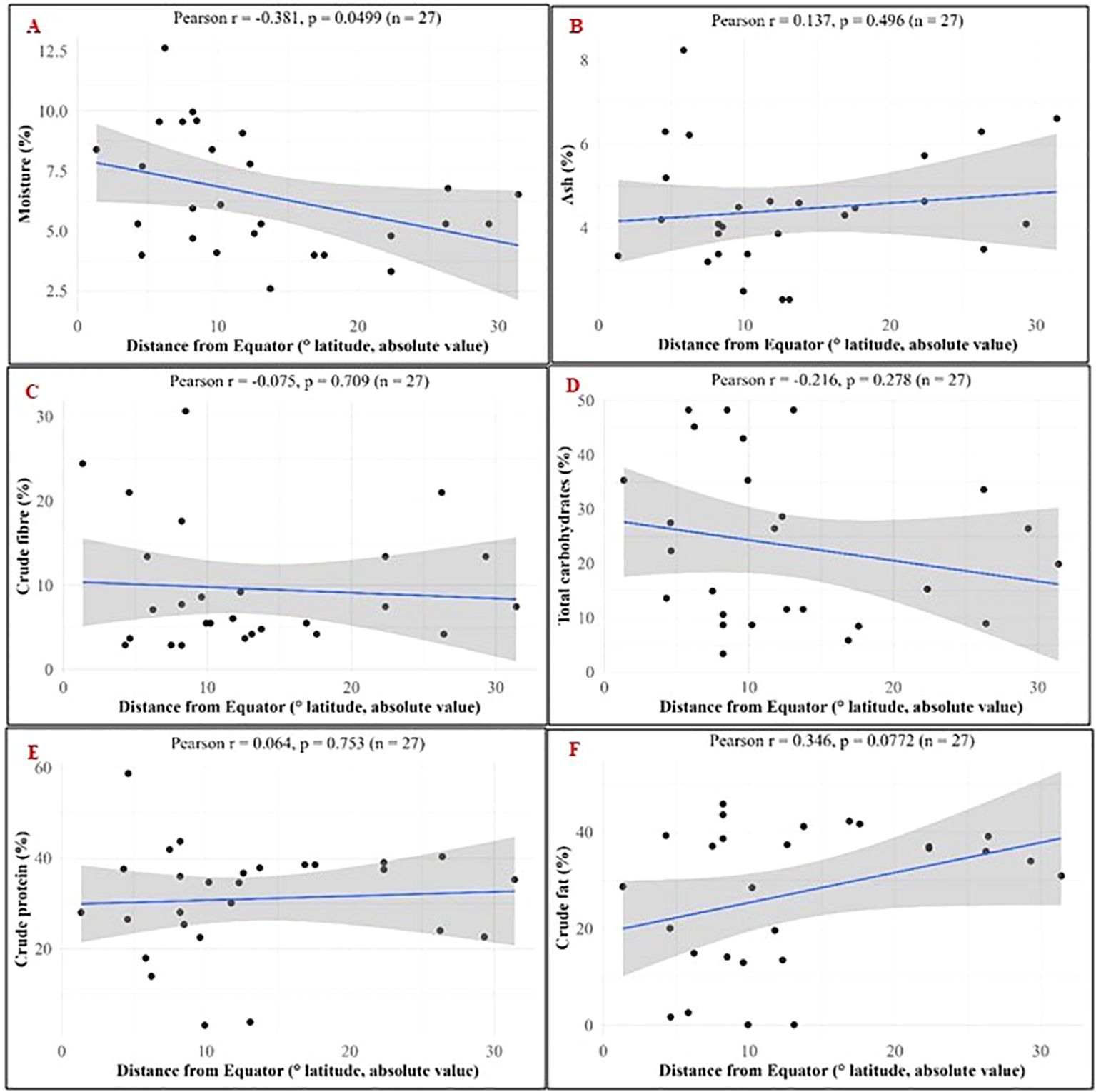

4.4 Correlation of nutritional components with distance from equator

The correlation of moringa seed nutritional components with the absolute distance from equator was also computed (Figures 7A–E). A moderate correlation was found for moisture (r = -0.381, p = 0.0499), crude fat (r = 0.346, p = 0.0772), and total carbohydrates ((r = -0.216, p = 0.278), (Figures 7A, F, D). The moisture content decreased with increasing distance of location from the equator. This negative correlation was statistically significant. But, positive correlation of the crude fat and negative correlation of the total carbohydrates with increasing latitude value was not statistically significant.

Figure 7. Pearson’s correlation of nutritional components in M. oleifera seeds with absolute distance from the equator. (A) Moisture; (B) Ash; (C) Crude fibre; (D) Total carbohydrates; (E) Crude protein; (F) Crude fat.

4.5 Influence of climatic zone on nutritional composition of M. oleifera seeds

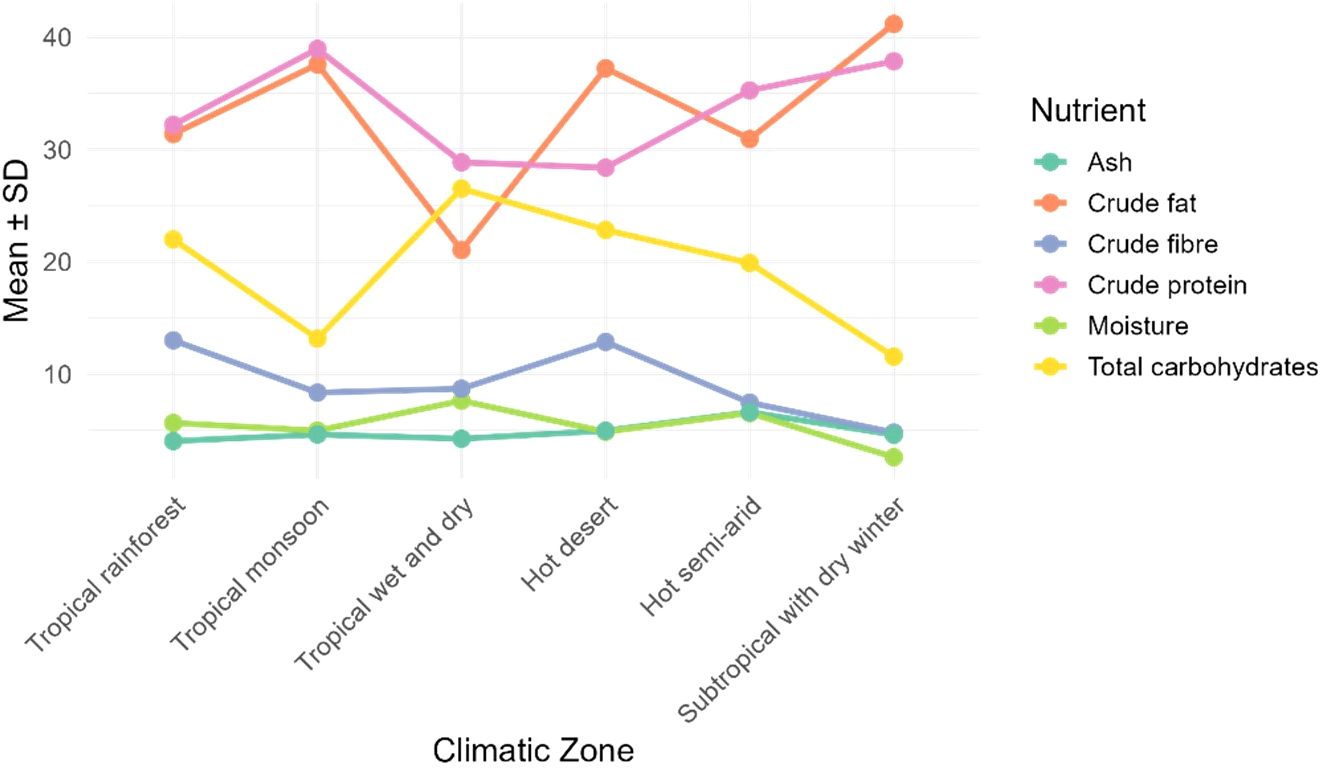

The mean values for each zone were computed and nutrient trend across climatic zone was plotted (Figure 8). The climatic zones were arranged in order of increasing temperature and distance from the equator. The ash and moisture varied least and moisture seems to decrease from tropics to subtropics. The crude fiber and total carbohydrates showed clearly a decreasing trend while crude protein and crude fat increased.

Figure 8. Nutritional trend in M. oleifera seeds across climatic zones, moving outwards from the equator and with decreasing mean temperature.

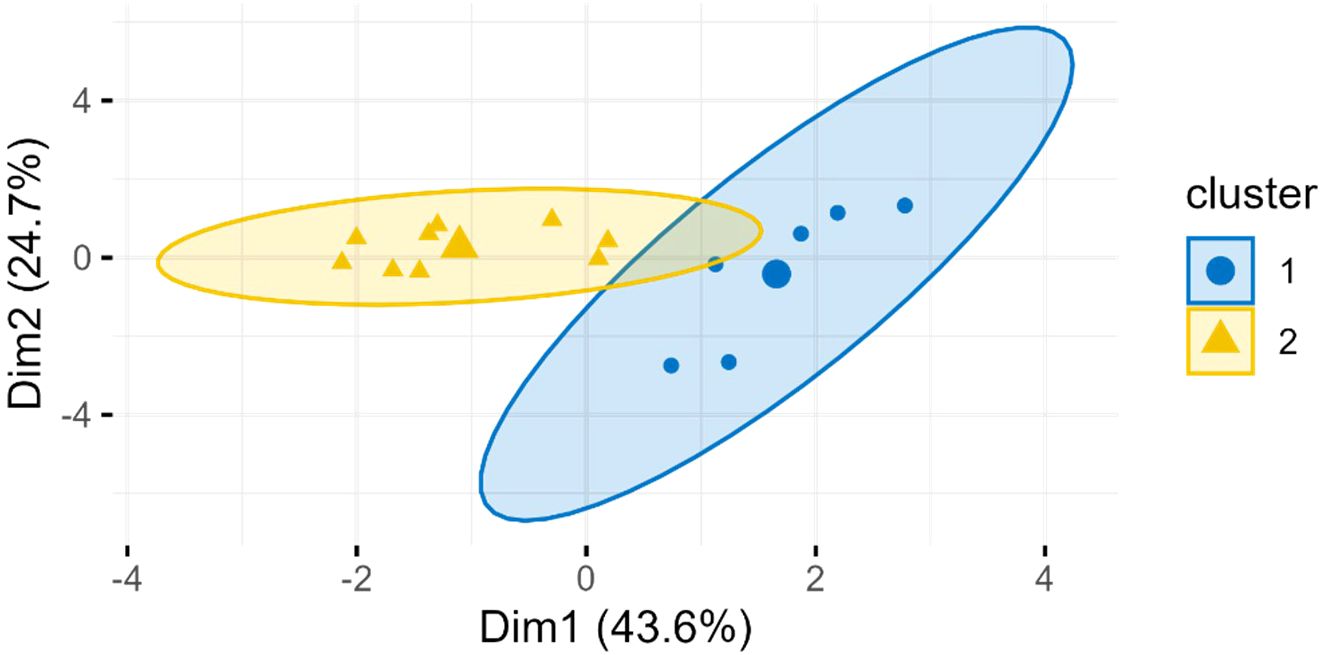

PCA + K-means clustering was used to divide tropical wet and dry zone data in two probable groups of different seasons. The zone is characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons, the data may represent nutrient profile of both as seen in Figure 9.

Figure 9. PCA+K-means clustering plot of M. oleifera seed proximate nutrients of tropical wet and dry climatic zone.

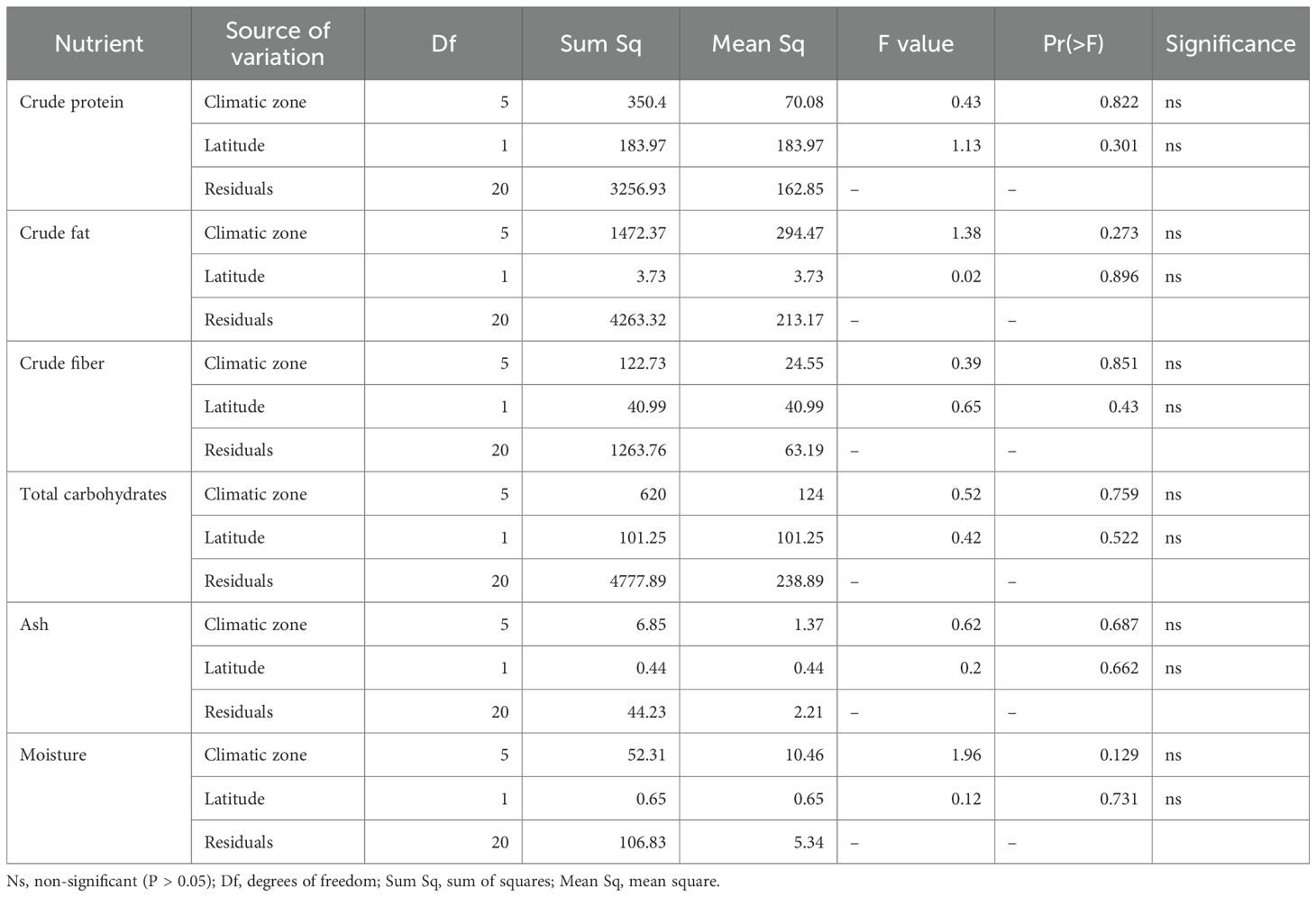

To evaluate the significance of the preliminary observations of nutrient composition trend across climatic zone analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed by taking climatic zone and latitude as categorical and continuous predictors respectively. Climatic zone had 5 degrees of freedom and latitude had 1 degree of freedom. The F-statistics were low, with corresponding p-values > 0.05 (Table 5). The 95% confidence intervals for all predictors overlapped zero, indicating non-significant variation across regions. Neither climatic zone nor latitude had statistically significant effect on any of the nutritional component. The residual variance with 20 degrees of freedom, accounted for most of the variability. Other models can’t be applied here because standard deviation and standard error were not uniformly reported in the selected studies.

5 Discussion

Moringa oleifera is majorly found in tropical and subtropical regions. The morphological variability exists in the seeds of the crop. Whitish seeds with pale yellow wings are reported in Pakistan (Anwar and Rashid, 2007), which is quite contrasting with other reports included in the study. It may represent a wild cultivar, as the seeds were collected from a forest. The seed weight and size varied with location and no correlation was present between two. This is in contrast to observations of Rafael et al. (2021), where a strong positive correlation was observed in seed morphometric parameters (length and width) with seed weight. This may be due to a lack of available research data and a deficiency of multiple imputation. The Egyptian seeds were exceptionally large in size with length 2.6 cm and width 2.4 cm, but multiple imputations predicted an intermediate weight (Table 4). The longer and wider seeds with spherical shape occupy more volume and hence a larger test weight is expected. Seed size and yield are strongly influenced by physiological state of plant or seed which is largely dependent on environmental stressors that may be naturally present in certain locations. Environmental cues activate gene expression of stress responsive genes that result in production of ROS, osmolytes and other defence substances. The stress in seed filling stages compromises on seed storage reserves and hence smaller seeds are produced (Das and Biswas, 2022).

There was no correlation between seed size index and the distance from equator. As the distance from the equator increases, the climate (temperature and rainfall) and nutrient status of soil changes (Hernández-Romero et al., 2024). The climatic and edaphic factors affect physiology of the crops and therefore it is expected as the distance from the equator changes. Absence of correlation with geography may indicates the involvement of genetic factors in determining morphological traits. But, genetically similar seeds of same tree and same pod may differ in size as reported by Noronha et al. (2018). Seeds size varies within a single fruit with respect to position. The largest seed is present at the base of a pod, and the size decreases along the length. Seed size indicates the quantity of reserve nutrients. Larger seeds accumulate higher quantity of carbohydrates, proteins and fats. This necessitates the further investigation on factors affecting seed morphological traits. There is scarcity of quantitative data pertaining to seed color and shape. Different studies reported white to brown colored moringa seeds and seed wings. Seed shape is also found to be variable from spherical to elliptical. Gupta et al. (2022) reported round seed kernel. In the absence of quantitative data, it was not feasible to draw any correlation of shape and color with geographical location. So, we were unable to eliminate chances of subjectivity in the analysis.

Moringa seeds are considered rich source of fat and proteins which is found true in our meta-analysis also. But the nutritional composition was variable across locations. Chelliah et al. (2017); Saa et al. (2022) and Mgbemena and Obodo (2016) reported very low crude fat content in moringa seeds, which was in contrast to other studies. Chelliah et al. (2017) also reported low crude protein content which was also contrasting the fact of moringa seed being a good protein source. Saa et al. (2022) also reported very high crude protein content in moringa seeds. Despite variation, we found a correlation among the nutritional components (Figure 6). The crude fat, crude protein and total carbohydrate are food reserves of the seeds. The strong correlation among them represents nutritional trade-off. Ash is an independent component. Low fat and protein content as reported by Chelliah et al. (2017) is consistent with positive correlation between them.

The nutritional composition was correlated with the latitude (absolute distance from equator) and climatic zone. Negative correlation of moisture with latitude was statistically significant. Generally, the atmospheric moisture and average rainfall of a location decreases with increasing distance from the equator and it was reflected in the moisture content of the moringa seeds also. A trend in crude fat, crude protein, crude fiber and total carbohydrate was observed across climatic zones when arranged in order of increasing distance from equator (Figure 7 and 8). These observations in nutritional composition were preliminary and further investigated by analysis of variance using climatic zone and latitude as variables. Effect of variables taken into consideration for current study had non-significant impact on nutritional trend. Other climatic factors may also contribute for these observations.

The time of flowering is highly variable in moringa crop. Some varieties flower twice a year while others annually (Dhakad et al., 2023). Hence, fruiting face different seasons. The seasonal variation affects reproductive aspects and fruit yield of moringa (Melo et al., 2020). In dry season, water availability is less, photosynthetic rate and hence, CO2 assimilation declines (Rivas et al., 2013). Iqbal and Bhanger (2006) reported the effect of seasonality along with location on M. oliefera leaves. The effect of season on oil content and quality has also been reported (Wiltshire et al., 2022). Correlating the seed quality attributes directly with geographical location without considering seasonal influence might present incomplete picture. The tropical wet and dry zone is characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons. The PCA+K-mean clustering plot suggested that the “Tropical Wet & Dry” climatic zone data likely contained two distinct sub-groups, which may represent two different seasons (Figure 9). Seasonal variations underscore the importance of temperature and rainfall in determining the nutritional composition of moringa seeds. The seasonal variations may also affect other zones, but sufficient data was not available.

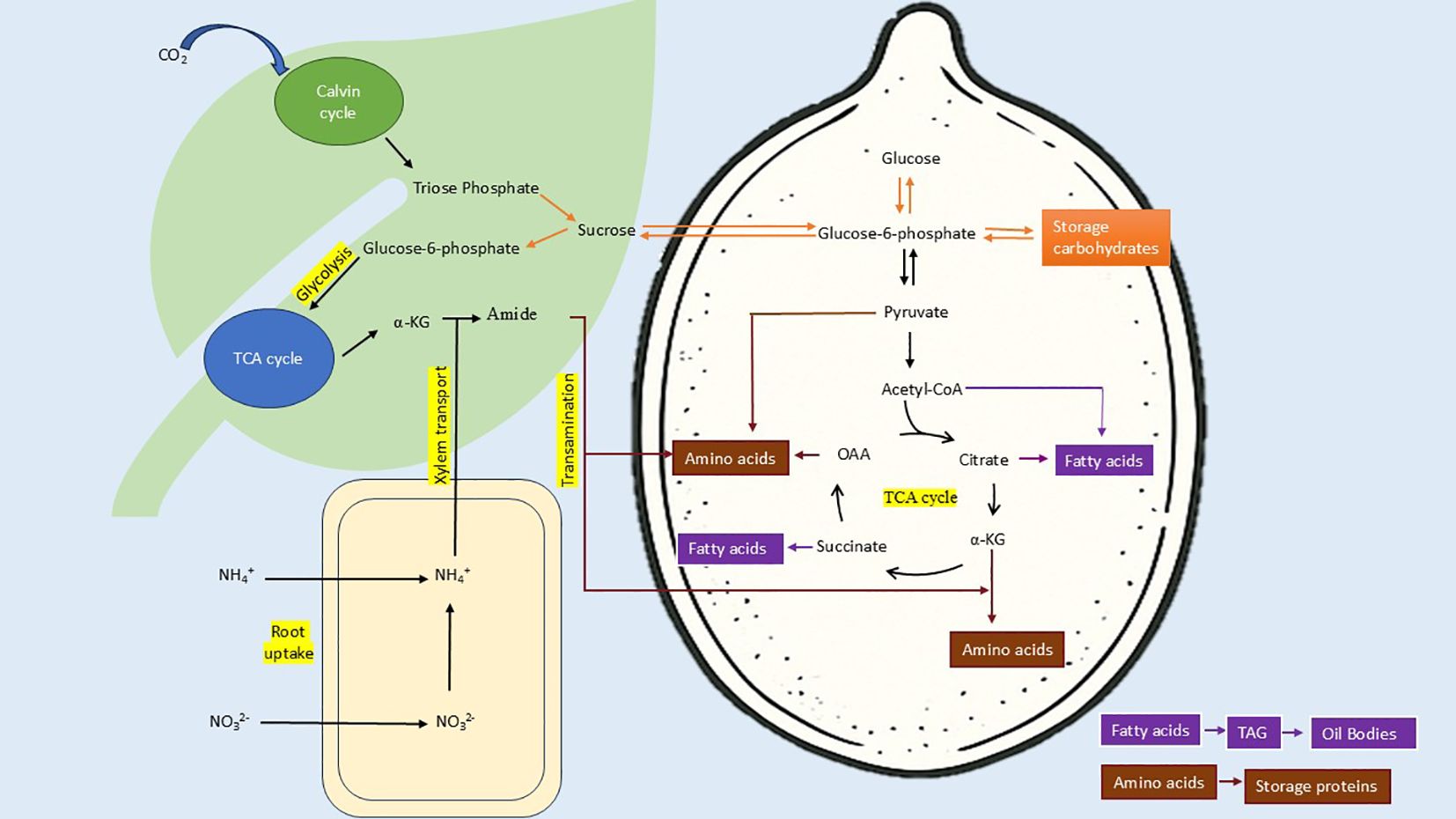

The widening gap between crude fat/crude protein and total carbohydrate food reserves (Figure 8), as we moved hotter to cooler climates, was consistent with the decreased photosynthesis and CO2 fixation. The availability of sunlight and water is higher in tropical regions (Huntley, 2023). The rate of photosynthesis maximizes to fix CO2 and more carbohydrates are synthesized and stored. On the other hand, nutritional status of soil significantly varies from tropics to temperate regions. The soil organic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus increase with decreasing temperature and rainfall (Hernández-Romero et al., 2024). This is due to higher nutrient cycling with increasing temperature. The availability of nitrogen favors the synthesis of proteins as we move away from the equator. In view of this, not the latitude or the climatic zone directly but indirectly influences the nutritional composition through temperature, rainfall and edaphic factors. Edaphic factors such as soil texture, pH, moisture availability, micronutrient balance, salinity etc. create a microenvironment by interacting with weather and climatic conditions. A thorough study with precise location along with accurate soil and weather data will help decipher the quality determining variables.

The stage of harvesting and seed processing also influence the nutritional status. Some researchers have removed hull before analysis while others have not. Seed hull being protective in nature is particularly rich in fiber and secondary metabolites (Saheed et al., 2019). It also has higher moisture content. Thus, it could affect the overall nutritional composition of the seeds. Environmental stresses not only affect seed morphometry but expression of defence related genes also influence the seed nutritional quality by activating new biochemical pathways or enhancing the metabolic flux through existing pathways. Production of secondary metabolites increases which compete for common metabolic precursors with seed storage reserves. Besides compromising yield for defence and adaptation, these specialized compounds provide medicinal values to the seeds. These generalized observations need further investigation in moringa with climatic variations.

In this analysis, a strong negative correlation (r = -0.73, p-value = 0) was observed in the total carbohydrates and the crude protein (Figure 6). This relationship can be traced back to carbon-nitrogen metabolism. The carbon-nitrogen metabolic pathways are related to each other (Figure 10). The negative correlation between the two is due to diversion of photosynthetic assimilates to nitrogen metabolism with increasing availability of soil nitrogen. CO2 fixation is not affected by nitrogen availability (Champigny, 1995). But, Triose phosphate, first stable product of photosynthesis, is partitioned more towards producing reducing equivalents for reduction of nitrate. After nitrogen uptake, a reasonable fraction of carbohydrates is mobilized to provide carbon skeleton for protein biosynthesis (Kaur et al., 2021). Temperature and radiation availability is higher at equator but nitrogen availability is low due to increased nitrogen cycling. With increasing distance from equator average temperature and radiation decreases and hence nitrogen availability increases. Therefore, an overall decrease in CO2 fixation with concomitant increase in nitrogen utilization is observed. Thus, negative correlation of carbohydrate and protein is observed with increasing distance from equator.

Figure 10. Schematic representation of carbon-nitrogen metabolism and accumulation of food reserves in seeds. Carbon dioxide is fixed in Calvin cycle to produce triose phosphate, which is used to synthesize sucrose for translocation via phloem. Sucrose is translocated to all parts of plant, provide assimilates to glycolysis and TCA cycle. Nitrate fixed in roots is reduced and transported via xylem and used in reductive amination of TCA intermediates via GS-GOGAT or Glutamate dehydrogenase mechanism to produce amides. These amides are translocated to developing seeds to provide amino group. Availability of amides promotes synthesis of amino acids by utilizing TCA intermediates and increases the metabolic flux via pathway. In the absence of amides, sucrose is mobilized to produce storage carbohydrates, which otherwise degraded to Acetyl-CoA and TCA intermediates. This process increases the availability of Acetyl-CoA, Citrate and Succinate for fatty acid synthesis. Fatty acids are incorporated in Triacylglycerols (TAGs) and stored in oil bodies. Amino acids are used for storage protein synthesis. (α-KG, α-Ketoglutarate; OAA, Oxaloacetate; TCA, Tricarboxylic acid; Carbohydrate metabolism, Amino acid metabolism, Fatty acid metabolism) .

The positive correlation between crude fat and protein (r =0.52, p = 0.005) is consistent with the observations of Maestri et al. (1998) in soyabean and Babatunde et al. (2022) in different parts of fruits and seeds of large number of plants. But these observations are in contrast to Hymowitz et al. (1972) and Filho et al. (2001). Our observations are also in contrast to observations of Azam et al. (2013) and Hossain et al. (2019) in Brassica napus. Oil and protein content are controlled by same SNP locus in Brassica napus (Tang et al., 2019). The positive correlation of the two could be because of overall increase in metabolic flux via Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle with changes in the C:N ratio of soil during seed filling. With decreasing C:N ratio (increased nitrogen availability), sucrose breakdown to provide C-skeleton via TCA cycle for amino acid and protein synthesis (Kaur et al., 2021). Glucose-6-phosphate, phosphoenolpyruvate and pyruvate are breakdown products of translocated sucrose and can be utilized as the carbon skeleton for fatty acid biosynthesis (Kubis et al., 2004) via TCA intermediates (Figure 10). Observations of Allen and Young (2013) were in agreement with our findings. C:N ratio affects protein accumulation while maintaining consistent rate dry weight accumulation. Glutamine not only supply carbon to amino acids; it supplies 9 to 19% carbon for fatty acid synthesis. Weigelt et al. (2008) demonstrated that increased N supply, initiates sucrose mobilization via sucrose synthase, glycolysis and TCA cycle to meet the demand of carbon acceptor for amino acid synthesis. This metabolic control is mediated by genetic regulation that sense changes in C:N ratio rather than N alone (Palenchar et al., 2004).

There was a positive correlation between total carbohydrates and moisture content in moringa seeds (r =0.46, p = 0.016). This is again in compliance with the trend in Figure 8 i.e. higher photosynthesis in higher moisture availability along with the sunlight which is the case at equator, in tropics. As the atmospheric moisture declines, in subtropics, moisture content and total carbohydrates decline together along with crude fibers in moringa seeds. Globally variations are high (Figure 5) but the observations of ANCOVA model (Table 5), ruled out the direct effect of climatic zone or latitude. Inter zonal variations are lower than the intra-zonal variations. Factors such as temperature, rainfall and soil nutrient status may have influence on the nutritional composition of moringa seeds.

A limitation of this study is that data extraction was conducted primarily by one reviewer, although all numerical values were independently verified for accuracy. Future studies may benefit from duplicate data extraction with inter-rater reliability assessment to further minimize extraction bias. Another limitation of our approach is that morphological and nutritional datasets could not be analytically integrated due to the absence of shared study identifiers. Future research incorporating paired datasets from coordinated sampling could enable correlation or multivariate modelling linking morphology and biochemical composition.

6 Conclusion

The spherical to oval shaped moringa seeds varied in color from whitish to brown. similarly, variability was found in the seed dimensions. Also, the current study did not observe any relationship among morphological traits, geographical location and climatic factors. Nutritional composition of moringa seeds was highly variable with highest variance (σ2) in crude fat (220.75), followed by total carbohydrate (211.51), crude protein (145.82) and crude fiber (54.90). As a preliminary observation, the tropical climates produce moringa seeds rich in carbohydrates while subtropical climates favor protein and fat accumulation. But statistical model fitting (ANCOVA) revealed that the latitude and the climatic zone are not deciding factors. The nutritional composition trend can be a function of rainfall (atmospheric moisture), temperature, sunlight and soil nutritional status. Further research is required to determine the effect of these climatic factors and involvement of genetic factors, if any.

The present study reports the correlation among nutritional components of moringa seeds. Total carbohydrates correlated negatively with crude fat and crude protein (r-value = -0.80 and 0.73 respectively) but positively with moisture and crude fiber (r = 0.46. and 0.43 respectively). Crude fat and crude protein had moderate positive correlation (r= 0.52) which is in contrast to related crops. These correlations were traced back to carbon-nitrogen metabolism and represented trade-off in seed storage reserves and consistent with the trend along latitudes. Further studies with more robust datasets can investigate the extent of influence of all possible climatic factors on this nutritional trade off in primary and secondary metabolites.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

PS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. JT: Validation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Supervision. AxB: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Validation. BK: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources. AM: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. CM: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Validation, Data curation. AjB: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The work was supported by SPARC-MHRD (Scheme for promotion of academic and research collaboration-Ministry of human resource development) Project ID-P-3753.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to CCS Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar for providing the necessary infrastructure and resources. We are also thankful to our colleagues especially Shivangi Bishnoi, Manju Rani and Rekha Rani for their support and suggestions that helped in timely completion of the work.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2026.1720005/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdalla, H. A., Ali, M., Amar, M. H., Chen, L., and Wang, Q. F. (2022). Characterization of Phytochemical and Nutrient Compounds from the Leaves and Seeds of M. oleifera oleifera and Moringa peregrina. Horticulturae 8, 1081. doi: 10.3390/horticulturae8111081

Abdulkadir, A. R., Zawawi, D. D., and Jahan, M. S. (2016). Proximate and phytochemical screening of different parts of Moringa oleifera. Russian Agric. Sci. 42, 34–36. doi: 10.3103/S106836741601002X

Abiodun, O. A., Adegbite, J. A., and Omolola, A. O. (2012). Chemical and physicochemical properties of Moringa flours and oil. Global J. Sci. Frontier Res. Biol. Sci. 12, 1–7. doi: 10.53555/nnas.v2i7.677

Allen, D. K. and Young, J. D. (2013). Carbon and nitrogen provisions alter the metabolic flux in developing soybean embryos. Plant Physiol. 161, 1458–1475. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.203299

Annongu, A., Karim, O. R., Toye, A. A., Sola-Ojo, F. E., Kayode, R. M. O., Badmos, A. H. A., et al. (2014). Geo-Assessment of chemical composition and nutritional Evaluation of Moringa oleifera seeds in nutrition of Broilers. J. Agric. Sci. 6, 119. doi: 10.5539/jas.v6n4p119

Anwar, F. and Rashid, U. (2007). Physico-chemical characteristics of Moringa oleifera seeds and seed oil from a wild provenance of Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 39 (5), 1443–1453.

Azam, S. M., Farhatullah, F., Adnan Nasim, A. N., Sikandar Shah, S. S., and Sidra Iqbal, S. I. (2013). Correlation studies for some agronomic and quality traits in Brassica napus L. Sarhad Journal of Agriculture 29 (4).

Babatunde, O., Ogunwale, O. P., Ajayi, O. O., and Ajayi, I. A. (2022). Correlation between oil, protein and carbohydrate content of plant seeds, skin and fruit pulp. J. Chem. Soc. Nigeria 47. doi: 10.46602/jcsn.v47i1.713

Banerji, R. and Bajpai, A. (2009). Oil and fatty acid diversity in genetically variable clones of Moringa oleifera from India. J. Oleo Sci. 58, 9–16. doi: 10.5650/jos.58.9

Beck, H. E., McVicar, T. R., Vergopolan, N., Berg, A., Lutsko, N. J., Dufour, A., et al. (2023). High-resolution (1 km) Köppen-Geiger maps for 1901–2099 based on constrained CMIP6 projections. Sci. Data 10, 724. doi: 10.1038/s41597-023–025496

Bellaloui, N., Hu, Y., Mengistu, A., Abbas, H. K., Kassem, M. A., and Tigabu, M. (2016). Elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide and temperature affect seed composition, mineral nutrition, and 15N and 13C dynamics in soybean genotypes under controlled environments. Atlas J. Plant Biol., 56–65. doi: 10.5147/AJPB.V0I0.114

Cambon, J., Hernangómez, D., Belanger, C., and Possenriede, D. (2021). tidygeocoder: An R package for geocoding. J. Open Source Software 6, 3544. doi: 10.21105/joss.03544

Champigny, M. L. (1995). Integration of photosynthetic carbon and nitrogen metabolism in higher plants. Photosynthesis Res. 46, 117–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00020422

Chatepa, L. E. C. and Mbewe, E. C. (2018). Proximate, physical and chemical composition of leaves and seeds of Moringa (Moringa oleifera) from Central Malawi: A potential for increasing animal food supply in the 21st century. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 13, 2872–2880. doi: 10.5897/AJAR2018.13535

Chelliah, R., Ramakrishnan, S., and Antony, U. (2017). Nutritional quality of Moringa oleifera for its bioactivity and antibacterial properties. Int. Food Res. J. 24, 825.

Coello, K. E., Frias, J., Martínez-Villaluenga, C., Cartea, M. E., Abilleira, R., and Peñas, E. (2020). Potential of germination in selected conditions to improve the nutritional and bioactive properties of moringa (Moringa oleifera L.). Foods 9, 1639. doi: 10.3390/foods9111639

Das, R. and Biswas, S. (2022). “Influence of abiotic stresses on seed production and quality,” in Seed biology updates. Ed. C. Jimenez-Lopez, J. (London, UNITED KINGDOM: IntechOpen). doi: 10.5772/intechopen.106045

Dhakad, A. K., Singh, M., Singh, S., Kapoor, R., Walia, G. S., and Dhillon, G. P. (2023). Phenological and floral variations in ecotypes of Moringa oleifera for reproductive adaptations in subtropical conditions. Indian J. Ecol. 50, 1701–1711. doi: 10.55362/IJE/2023/4121

Ebeid, H. M., Kholif, A. E., Chrenkova, M., and Anele, U. Y. (2020). Ruminal fermentation kinetics of Moringa oleifera leaf and seed as protein feeds in dairy cow diets: in sacco degradability and protein and fiber fractions assessed by the CNCPS method. Agroforestry Syst. 94, 905–915. doi: 10.1007/s10457-019-00456-7

Fagwalawa, L., Yahaya, S., and Umar, D. (2014). A comparative proximate analysis of bark, leaves and seeds of Moringa oleifera. Int. J. Basic Appl. Chem. Sci. 5, 56–62.

Filho, M. M., Destro, D., Miranda, L. A., Spinosa, W. A., Carrão-Panizzi, M. C., and Montalván, R. (2001). Relationships among oil content, protein content and seed size in soybeans. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 44, 23–32. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89132001000100004

Gandji, K., Tovissodé, F. C., Azihou, A. F., Akpona, J. D. T., Assogbadjo, A. E., and Kakaï, R. L. G. (2020). Morphological diversity of the agroforestry species Moringa oleifera Lam. as related to ecological conditions and farmers’ management practices in Benin (West Africa). South Afr. J. Bot. 129, 412–422. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2019.10.004

Gopalakrishnan, L., Doriya, K., and Kumar, D. S. (2016). Moringa oleifera: A review on nutritive importance and its medicinal application. Food Sci. Hum. wellness 5, 49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2016.04.001

Gupta, N., Chinnappa, M., Singh, P. M., Kumar, R., and Sagar, V. (2022). Determination of the physio-biochemical changes occurring during seed development, maturation, and desiccation tolerance in Moringa oleifera Lam. South Afr. J. Bot. 144, 430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2021.09.010

Guzmán-Maldonado, S. H., López-Manzano, M. J., Madera-Santana, T. J., Núñez-Colín, C. A., Grijalva-Verdugo, C. P., Villa-Lerma, A. G., et al. (2020). Caracterización nutricional de hojas, semillas, cáscara y flores de Moringa oleifera de dos regiones de México. Agronomía Colombiana. 38, 287-297. doi: 10.15446/agron.colomb.v38n2.82644

Hamada, F. A., Sabah, S. S., Mahdy, E., El-Raouf, H. S. A., El-Taher, A. M., El-Leel, O. F., et al. (2024). Genetic, phytochemical and morphological identification and genetic diversity of selected Moringa species. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-79148-x

Hernández-Romero, Á.H., Perroni, Y., Sánchez Velásquez, L. R., Martínez-Hernández, S., Ávila-Bello, C. H., Xu, X., et al. (2024). Soil C: N: P stoichiometric signatures of grasslands differ between tropical and warm temperate climatic zones. Biogeochemistry 167, 909–926. doi: 10.1007/s10533-024-01143-1

Hossain, Z., Johnson, E. N., Wang, L., Blackshaw, R. E., and Gan, Y. (2019). Comparative analysis of oil and protein content and seed yield of five Brassicaceae oilseeds on the Canadian prairie. Ind. Crops Products 136, 77–86.

Huntley, B. J. (2023). “Solar energy, temperature and rainfall,” in Ecology of Angola: terrestrial biomes and ecoregions (Springer International Publishing, Cham), 95–125. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-18923-4_5

Hymowitz, T., Collins, F. I., Panczner, J., and Walker, W. M. (1972). Relationship between the content of oil, protein, and sugar in soybean seed 1. Agron. J. 64, 613–616. doi: 10.2134/agronj1972.00021962006400050019x

Illingworth, K. A., Lee, Y. Y., and Siow, L. F. (2022). The effect of isolation techniques on the physicochemical properties of Moringa oleifera protein isolates. Food Chem. Adv. 1, 100029. doi: 10.1016/j.focha.2022.100029

Ilyas, M., Arshad, M. U., Saeed, F., and Iqbal, M. (2015). Antioxidant potential and nutritional comparison of moringa leaf and seed powders and their tea infusions. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 25, 226–233.

Iqbal, S. and Bhanger, M. I. (2006). Effect of season and production location on antioxidant activity of Moringa oleifera leaves grown in Pakistan. J. Food Composition Anal. 19, 544–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2005.05.001

Kaur, M., Tak, Y., Bhatia, S., Asthir, B., Lorenzo, J. M., and Amarowicz, R. (2021). Crosstalk during the carbon–nitrogen cycle that interlinks the biosynthesis, mobilization and accumulation of seed storage reserves. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 12032. doi: 10.3390/ijms222112032

Kimbonguila, A., Nzikou, J. M., Matos, L., Loumouamou, B., Ndangui, C. B., Pambou-Tobi, N. P. G., et al. (2010). Proximate composition of selected Congo oil seeds and physicochemical properties of the oil extracts. Res. J. Appl. Sciences Eng. Technol. 2, 60–66.

Kubis, S. E., Pike, M. J., Everett, C. J., Hill, L. M., and Rawsthorne, S. (2004). The import of phosphoenolpyruvate by plastids from developing embryos of oilseed rape, Brassica napus (L.), and its potential as a substrate for fatty acid synthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1455–1462. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh157

Labbassi, S., Tahiri, A., Mimouni, A., Chabbi, N., Telmoudi, M., Afi, C., et al. (2024). Argo-morphological and genetic diversity of Moringa oleifera grown in Morocco under a semi-arid climate. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol., 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10722-024-02047-7

Lemenkova, P. (2020). Using R Packages' tmap', 'raster' and' ggmap' for Dartographic Visualization: An Example of Dem-Based Terrain Modelling of Italy, Apennine Peninsula. Zbornik radova-Geografski fakultet Univerziteta u Beogradu 68, 99–116. doi: 10.5937/zrgfub2068099L

Liang, L., Wang, C., Li, S., Chu, X., and Sun, K. (2019). Nutritional compositions of Indian Moringa oleifera seed and antioxidant activity of its polypeptides. Food Sci. Nutr. 7, 1754–1760. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1015

Maestri, D. M., Guzmán, G. A., and Giorda, L. M. (1998). Correlation between seed size, protein and oil contents, and fatty acid composition in soybean genotypes. Grasas y Aceites 49, 450–453. doi: 10.3989/gya.1998.v49.i5-6.757

Melo, A. S., Benitez, L. C., and Barbosa, V. S. (2020). Environmental seasonality influences on reproductive attributes of Moringa oleifera. Pesquisa Florestal Bras. 40. doi: 10.4336/2020.pfb.40e201801745

Mgbemena, N. M. and Obodo, G. A. (2016). Comparative Analysis of Proximate and mineral composition of Moringa oleifera root, leave and seed obtained in Okigwe Imo State, Nigeria. J. Mol. Stud. Med. Res. 1, 57–62. doi: 10.18801/jmsmr.010216.07

Mulugeta, G. and Fekadu, A. (2014). Industrial and agricultural potentials of Moringa. Carbon 45, 1–08.

Musa, J. and Njidda, A. A. (2021). Chemical composition, anti-nutritive substances, amino acid profile and mineral composition of Moringa oleifera seeds subjected to different boiling duration. Nigerian J. Anim. Sci. Technol. (NJAST) 4, 43–52.

Noronha, B. G., Pereira, M. D., Flores, A. V., Demartelaere, A. C. F., and De Medeiros, A. D. (2018). Morphometry and physiological quality of Moringa oleifera seeds in the function of their fruit position. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 25, 1–10. doi: 10.9734/jeai/2018/43375

Ogunsina, B. S., Olumakaiye, M. F., Chinma, C. E., and Akomolafe, O. P. (2015). Effect of hydrothermal processing on the proximate composition and organoleptic characteristics of dehulled Moringa oleifera seeds. Nutr. Food Sci. 45, 944–953. doi: 10.1108/NFS-04-2015-0036

Olagbemide, P. T. and Philip, C. N. A. (2014). Proximate analysis and chemical composition of raw and defatted Moringa oleifera kernel. Adv. Life Sci. Technol. 24, 92–99.

Palenchar, P. M., Kouranov, A., Lejay, L. V., and Coruzzi, G. M. (2004). Genome-wide patterns of carbon and nitrogen regulation of gene expression validate the combined carbon and nitrogen (CN)-signaling hypothesis in plants. Genome Biol. 5, R91. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-11-r91

Pandey, V. N., Chauhan, V., Pandey, V. S., Upadhyaya, P. P., and Kopp, O. R. (2019). Moringa oleifera Lam.: a biofunctional edible plant from India, phytochemistry and medicinal properties. J. Plant Stud. 8, 10. doi: 10.5539/jps.v8n1p10

Qaderi, M. M., Martel, A. B., and Strugnell, C. A. (2023). Environmental factors regulate plant secondary metabolites. Plants 12, 447. doi: 10.3390/plants12030447

Rai, S. K., Pal, A. K., Pandey, J., and Dayal, A. (2023). Moringa: A bioactive elixir for nutrition, ecology and prosperity. Indian Farming 73, 21–24.

Rafael, R. H., Martha, H. R., Cruz Monterrosa Rosy, G., Mayra, D. R., Judith, J. G., León-Espinosa, Erika B., et al. (2021). Morphological characterization of Moringa oleifera seeds from different crops of Mexico. Agro Productividad. doi: 10.32854/agrop.v14i11.2175

Rajendran, C., Kirtana, S., Rashmi, V., Yadav, P., and Anilakumar, K. R. (2020). Nutritional and anti-oxidant potential of commonly growing planfoods from southern India. Defence Life Sci. J. 5. doi: 10.14429/dlsj.5.13959

Ramos, L. M., Costa, R. S., Môro, F. V., and Silva, R. C. (2010). Morfologia de frutos e sementes e morfofunção de plântulas de Moringa (Moringa oleifera Lam.). Comunicata Scientiae 1, 156–156. doi: 10.9734/JEAI/2018/43375

Rani, B., Devi, T., Kumari, N., Rani, P., Duhan, J., and Lavisha (2025). A comprehensive overview of nutritional and bioactive compounds of Moringa oleifera seeds. Int. J. Advanced Biochem. Res. 9, 315–323. doi: 10.33545/26174693.2025.v9.i8e.5172

Rivas, R., Oliveira, M. T., and Santos, M. G. (2013). Three cycles of water deficit from seed to young plants of Moringa oleifera woody species improves stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 63, 200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.11.026

Ruiz-Hernández, R., Hernández-Rodríguez, M., Cruz-Monterrosa, R. G., Díaz-Ramírez, M., Jiménez-Guzmán, J., León-Espinosa, E. B., et al. (2021). Morphological characterization of Moringa oleifera seeds from different crops of Mexico. Agro Productividad. doi: 10.32854/agrop.v14i11.2175

Saa, R. W., Fombang Nig, E., Radha, C., Ndjantou, E. B., and Njintang Yanou, N. (2022). Effect of soaking, germination, and roasting on the proximate composition, antinutrient content, and some physicochemical properties of defatted Moringa oleifera seed flour. J. Food Process. Preservation 46, e16329. doi: 10.1111/jfpp.16329

Saheed, I. A., Aliyu, N., Muhammed, M., and Oluwasegun, A. N. (2019). Evaluation of proximate content and vitamin profile of Moringa oleifera seed hull. Int. J. Livestock Production 10, 188–191. doi: 10.5897/IJLP2018.0512

Sodamade, A., Owonikoko, A. D., and Owoyemi, D. S. (2017). Nutrient contents and mineral composition of Moringa oleifera Seed. Int. J. Communication Syst. 5, 205–207.

Stadtlander, T. and Becker, K. (2017). Proximate composition, amino and fatty acid profiles and element compositions of four different Moringa species. J. Agric. Sci. 9, 46–57. doi: 10.5539/jas.v9n7p46

Tang, M., Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., Tong, C., Cheng, X., Zhu, W., et al. (2019). Mapping loci controlling fatty acid profiles, oil and protein content by genome-wide association study in Brassica napus. Crop J. 7, 217–226.

Umerah, N. N., Asouzu, A. I., and Okoye, J. I. (2019). Effect of processing on the nutritional composition of Moringa olifera Leaves and Seeds. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 11, 124–135. doi: 10.9734/ejnfs/2019/v11i330155

van Buuren, S. and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Software 45, 1–67. doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03

Weigelt, K., Küster, H., Radchuk, R., Müller, M., Weichert, H., Fait, A., et al. (2008). Increasing amino acid supply in pea embryos reveals specific interactions of N and C metabolism, and highlights the importance of mitochondrial metabolism. Plant J. 55, 909–926.

Wiltshire, F. M. S., de França Santos, A., Silva, L. K. B., de Almeida, L. C., dos Santos Freitas, L., Lima, A. S., et al. (2022). Influence of seasonality on the physicochemical properties of Moringa oleifera Lam. Seed oil and their oleochemical potential. Food Chemistry: Mol. Sci. 4, 100068. doi: 10.1016/j.fochms.2021.100068

Xue, W. T., Gianinetti, A., Wang, R., Zhan, Z. J., Yan, J., Jiang, Y., et al. (2016). Characterizing barley seed macro-and micro-nutrients under multiple environmental conditions. Cereal Res. Commun. 44, 639–649. doi: 10.1556/0806.44.2016.031

Keywords: climatic zone, crude protein, moringa seed, morphological variability, nutritional composition, carbon-nitrogen metabolism

Citation: Sharma P, Tokas J, Bhuker A, Kamboj BR, Malik A, McGill CR and Bhardwaj AK (2026) Geographical variability in morphology and nutritional composition of Moringa oleifera seeds: a meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 17:1720005. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2026.1720005

Received: 07 October 2025; Accepted: 12 January 2026; Revised: 04 December 2025;

Published: 09 February 2026.

Edited by:

Zeynep Aksoylu Özbek, Manisa Celal Bayar University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Maria Dolores Ortolá ortolá, Universitat Politècnica de València, SpainFrancois Mitterand Tsombou, Fujairah Research Centre, United Arab Emirates

Copyright © 2026 Sharma, Tokas, Bhuker, Kamboj, Malik, McGill and Bhardwaj. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jayanti Tokas, aml5YWNjc2hhdUBnbWFpbC5jb20=; Ajay Kumar Bhardwaj, YWpheWtiaGFyZHdhakBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Preeti Sharma1,2

Preeti Sharma1,2 Jayanti Tokas

Jayanti Tokas Ajay Kumar Bhardwaj

Ajay Kumar Bhardwaj