- 1State Key Laboratory for Development and Utilization of Forest Food Resources, State Key Laboratory of Tree Genetics and Breeding, The Southern Modern Forestry Collaborative Innovation Center, College of Life Sciences, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China

- 2Forestry and Pomology Research Institute, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Protected Horticultural Technology, Shanghai Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Shanghai, China

- 3Shenzhen Research Institute, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, China

Lycoris radiata, known for its striking floral patterns and vivid colors, holds significant ornamental value and is widely admired by the public. As research on Lycoris species progresses, scientists have uncovered their significant medicinal potential. These plants are particularly valued for their alkaloid compounds, which exhibit important pharmacological properties, especially strong antibacterial effects. This study systematically investigates the medicinal properties of Lycoris alkaloids. Through a comprehensive review, we analyze the various types of alkaloids present in Lycoris species. It sheds light on their synthetic mechanisms and elucidates their multifaceted functions, providing a detailed understanding of their pharmacological potential. Moreover, this paper highlights recent breakthroughs in alkaloid research, presenting the latest advancements in this field. By systematically documenting and elucidating these aspects, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the medicinal value of Lycoris and the intricate roles played by its alkaloid constituents.

1 Introduction

1.1 Introduction to Lycoris

Lycoris, a perennial monocotyledonous herb of the genus Lycoris (Amaryllidaceae), is native to subtropical East Asia, including China, Korea, Japan, and Taiwan (Tae and Go, 1995).This genus contains approximately 20 species, with 15 present in China (Tae and Ko, 1993). These species are predominantly found in the southern region of the Yangtze River, particularly Jiangsu, Anhui, and Zhejiang Provinces. Lycoris plants typically thrive in damp and cool environments, such as brook rocks. Their bulbs are covered with dark brown membranous scales, and their leaves are flat and elongated, resembling narrow strips. This morphological similarity to garlic explains the origin of the genus name “Lycoris”. First described by Herbert in 1821 (Ping-sheng et al., 1994), the genus has gained research significance, with Lycoris aurea becoming a model organism because of its distinctive traits and high interspecific cross-compatibility (Zhang et al., 2020). The frequent natural hybridization within the genus offers valuable opportunities to study the genetic and physiological diversity of Lycoris (Lv et al., 2023). Lycoris radiata (L’Hér.) Herb., commonly referred to as red spider lily or stone garlic, has been extensively utilized in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) as an ethnopharmacologically significant plant (Liao et al., 2012). The bulbs of L. radiata contain a variety of bioactive Amaryllidaceae alkaloids, which have been employed in folk medicine for the management of neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), other neurodegenerative conditions, and poliomyelitis (Chen et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2019). As documented in the Compendium of Materia Medica (Ben Cao Gang Mu), L. radiata exhibits therapeutic properties such as detoxification, analgesia, anti-inflammatory effects, and diuresis, and has been traditionally applied in the treatment of abscesses, suppurative wounds, and ulcers (Jin and Yao, 2019). Modern pharmacological studies have validated these traditional uses, demonstrating that its active components (e.g., lycorine and galanthamine) possess neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities (Shen et al., 2019).

In recent years, Lycoris has attracted considerable research interest owing to its medicinal potential, which is primarily attributed to the presence of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids in its bulbs (Ding et al., 2017). These alkaloids demonstrate diverse pharmacological activities, including antimalarial (Hao et al., 2013; Toriizuka et al., 2008), antiviral (Szlávik et al., 2004; Zou et al., 2009), and immunostimulatory effects (Liao et al., 2012). Notably, isoquinoline alkaloids from the Amaryllidaceae family have shown significant potential in drug discovery and development. These compounds have been traditionally used for their antiseptic and wound-healing properties, as well as for treating alcoholism (Nair and van Staden, 2019). Notably, galantamine, a representative alkaloid derived from Lycoris, has been clinically approved for treating mild-to-moderate AD (Howes and Houghton, 2003). Another key compound, lycorine, exhibits broad-spectrum bioactivities including antibacterial, antimalarial, and cardioprotective effects. These bioactive constituents highlight Lycoris as a promising source for natural drug development (Zhao et al., 2023).

With the intensification of ageing of the global population, the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases has increased, leading to a growing demand for galantamine (Wang et al., 2024). However, the complex structure of galantamine poses significant challenges in chemical synthesis, making large-scale commercial production through total chemical synthesis difficult (Yeo et al., 2021). Consequently, the extraction of natural galantamine from Lycoris bulbs has become increasingly important. Chinese researchers reported in 2014 that global galantamine production (300–400kg/year) met less than 0.2% of the annual worldwide demand (175,000–263,000 kg/year). Currently, Lycoris serves as the primary source for galantamine production in China, resulting in rapidly growing market demand(X. Chang, 2015).

China possesses abundant species diversity in the Lycoris genus, yet most populations remain in wild conditions (Zhang et al., 2021). The rising market demand for cut flowers and for medicinal purposes has caused excessive bulb harvesting, posing severe threats to wild populations because of habitat destruction. Additionally, the natural reproduction of Lycoris faces biological constraints. Its regeneration efficiency in the wild is low—typically, only one or two axillary buds sprout and form bulbs annually (Ren et al., 2022). The long growth cycle further hinders commercial-scale cultivation. Although tissue culture techniques provide partial solutions, traditional micropropagation systems still face multiple challenges. These include callus browning, vitrification, microbial contamination, low induction/proliferation efficiency, and poor acclimatization resulting in low transplant survival rates (Zhang et al., 2024).

While more than 230 Lycoris cultivars are currently used as ornamental garden plants, their alkaloid concentrations remain extremely low. For instance, less than 0.1% galantamine is present in Lycoris radiata. Consequently, the demand for Lycoris bulbs remains high. Beyond meeting this demand, enhancing the alkaloid content represents another key research focus. Studies indicate that the alkaloid levels in the same species vary across habitats, and researchers have explored the introduction of endophytic fungi to Lycoris bulbs to increase alkaloid production (Wang et al., 2024).

1.2 Alkaloid species in Lycoraceae

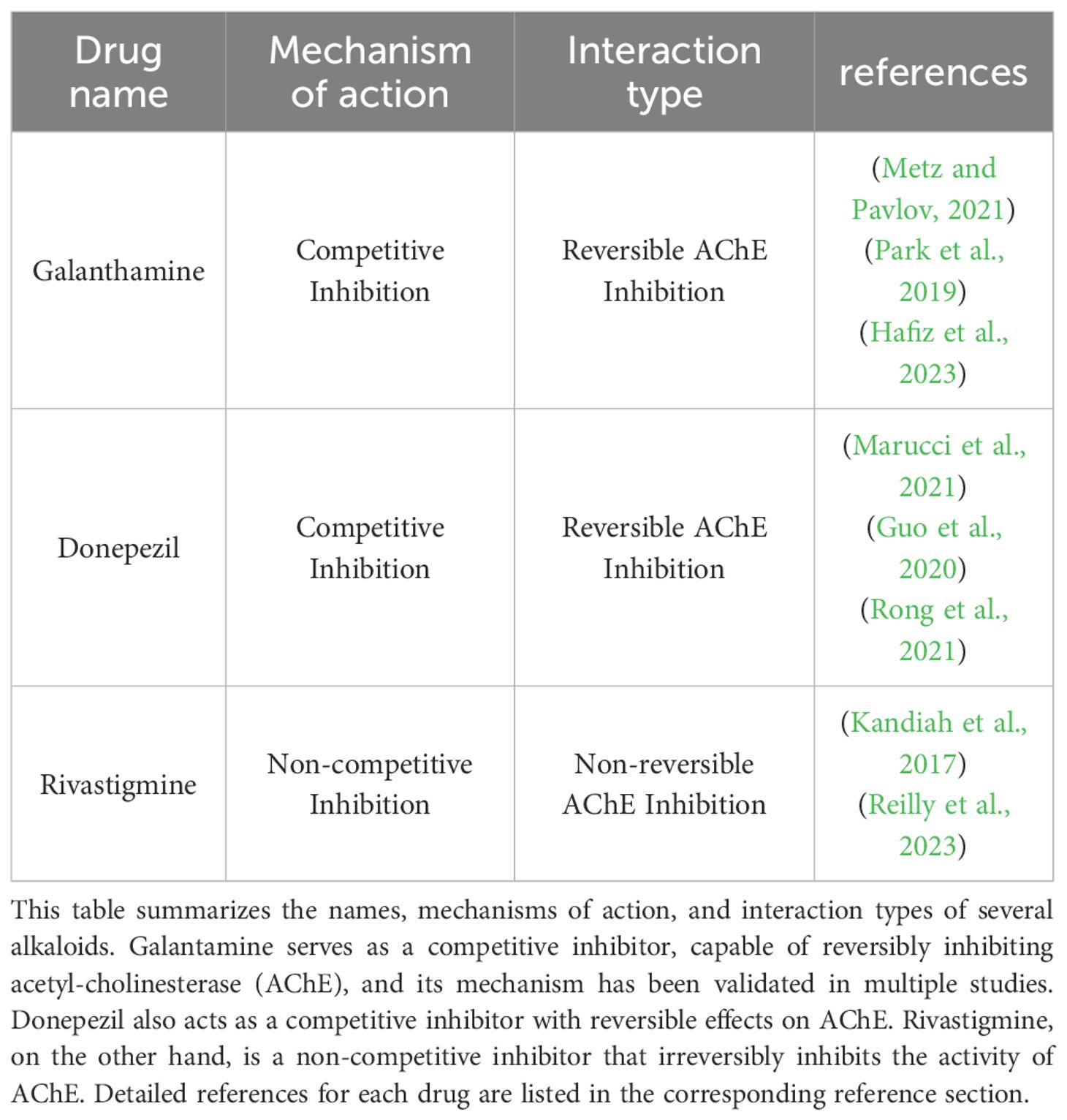

The Lycoris genus is widely recognized for its diverse alkaloid profiles, with hundreds of compounds having been isolated and characterized (Cahlíková et al., 2020). As documented in the Flora of China (Fennell and van Staden, 2001), the genus has 15 species in China, including L. albiflora, L. anhuiensis, L. aurea, L. caldwellii, L. chinensis, L. guangxiensis, L. houdyshelii, L. incarnata, L. longituba, L. radiata, L. rosea, L. shaanxiensis, L. sprengeri, L. squamigera, and L. straminea. These species possess both ornamental and medicinal value. This study focuses on the morphological characterization of 18 representative Lycoris species. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diversity and characteristics of 18 species of Lycoris. (A) Lycoris radiata var. pumila, (B) Lycoris rosea, (C) Lycoris sprengeri, (D) Lycoris sanguinea var. sanguinea, (E) Lycoris sanguinea koreana, (F) Lycoris longituba var. flava, (G) Lycoris longituba, (H) Lycoris anhuiensis, (I) Lycoris chinensis, (J) Lycoris aure, (K) Lycoris chinensis x Lycoris sprengeri, (L) Lycoris caldwellii, (M) Lycoris albifora, (N) Lycoris incarnata, (0) Lycoris straminea, (P) Lycoris flavescens, (Q) Lvcoris radiata, (R) Lycoris chunxiaoensis.

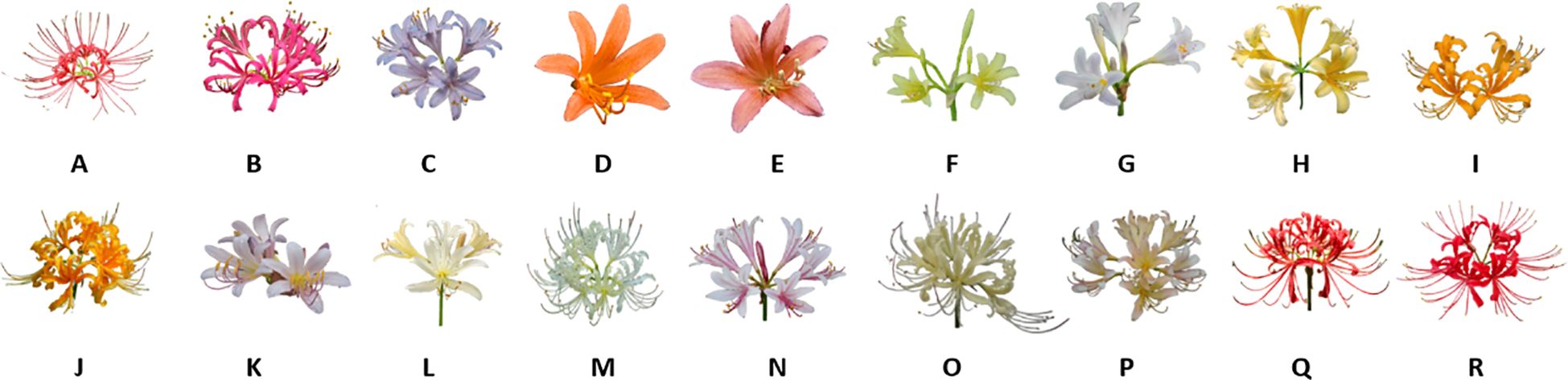

Lycoris alkaloids, which are tyrosine-derived compounds predominantly biosynthesized by the Amaryllidaceae family, represent a structurally diverse group of plant metabolites. Current research has identified 636 distinct alkaloids from Lycoris species, with complete structural elucidation achieved for more than 100 compounds (Jin and Yao, 2019). These nitrogenous secondary metabolites are categorized into 18 major structural classes: norbelladine-, lycorine-, homolycorine-, galasine-, galanthindole-, crinine-, haemanthamine-, cripowellin-, narciclasine-, pretazettine-, plicamine-, secoplicamine-, graciline-, montanine-, galanthamine-, ismine-, and Sceletium-type alkaloids, along with miscellaneous derivatives (Georgiev et al., 2024). Of particular importance is galanthamine, which has been rigorously investigated as a potential therapeutic agent for AD (Marco-Contelles et al., 2006). Representative alkaloid structures are presented in Figure 2. This remarkable structural diversity positions Lycoris alkaloids as valuable candidates for pharmaceutical development.

Figure 2. The species of alkaloids in Lycoraceae. (A) Lycorine, (B) Norbelladine, (C) plicamine, (D) homolycorine, (E) crinine, (F) graciline, (G) haemanthamine, (H) galanthamine, (I) galanthindole, (J) phenanthridone, (K) tazettine, (L) montanine, (M) miscellaneous, (N) phenanthridine.

1.3 Systematic review of alkaloids in the Lycoris genus

1.3.1 Chemical diversity of lycorine alkaloids in Lycoris species

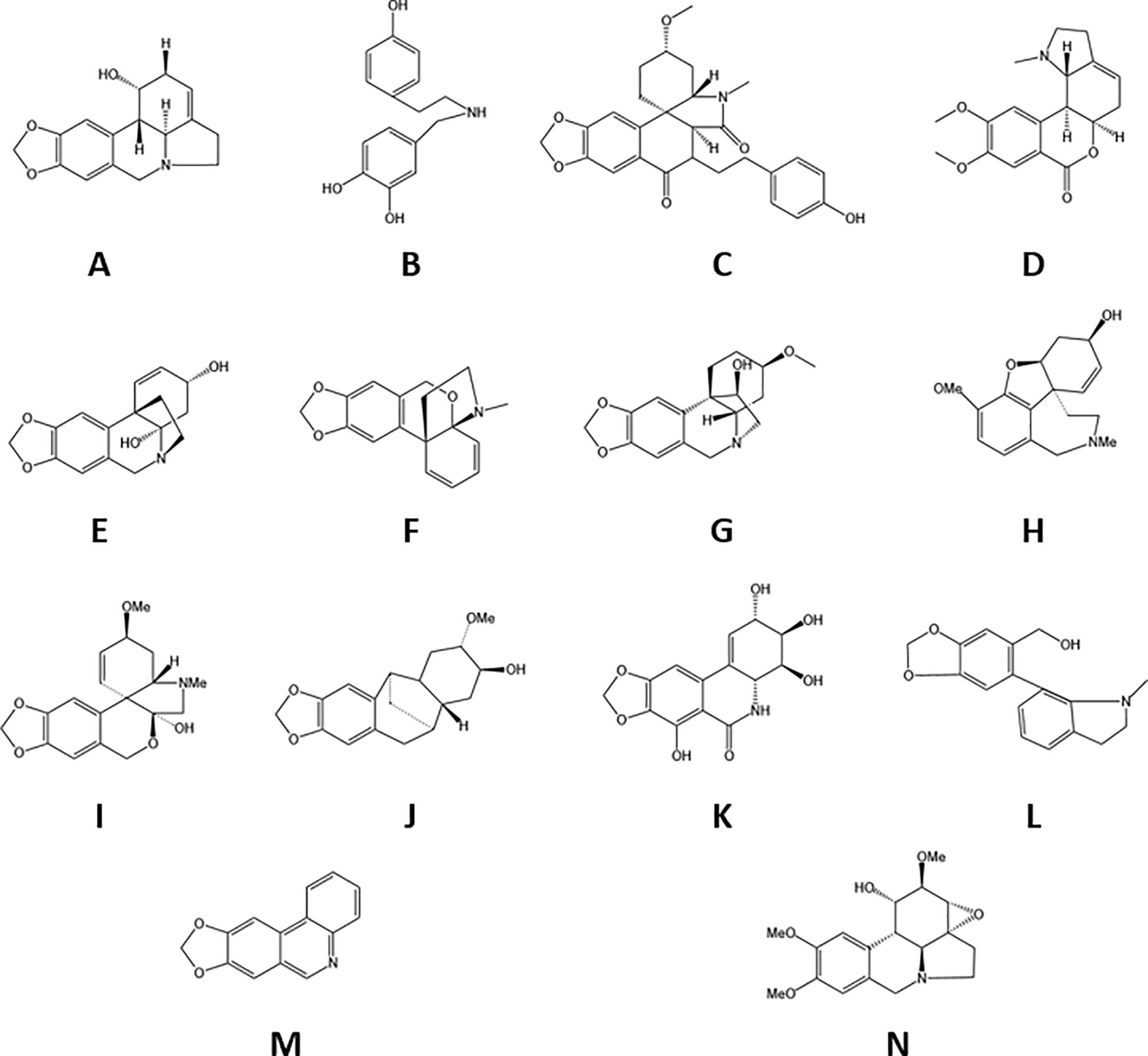

Owing to its economic significance, ornamental value, and potential therapeutic applications for neurological disorders, the Lycoris genus has become increasingly important in the Amaryllidaceae family (Ren et al., 2021, Ren et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2020). The genus derives its common name from the bulb’s morphological similarity to garlic. However, its taxonomic classification remains challenging because of widespread interspecific hybridization, which has produced numerous hybrids with highly similar morphological characteristics among varieties (Quan et al., 2024). According to Plants of the World Online (POWO);, 29 Lycoris species are currently documented, with 25 being taxonomically accepted. Our alkaloid research analysis revealed that the alkaloid contents of 18 species, which produce approximately 120 characterized alkaloids, have been studied (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 1). Notably, L. radiata var. pumila is recognized as a distinct variety, whereas L. anhuiensis and L. straminea have been reported in only a single Chinese study. Among the investigated species, L. radiata (red spider lily) has the most diverse alkaloid profile and is the most extensively studied taxon. Several other species—including L. aurea, L. longituba, L. sprengeri, L. squamigera, and L. incarnata—also demonstrate considerable alkaloid diversity and abundance (Cahlíková et al., 2020).

Figure 3. Quantification of identified alkaloids across Lycoris species. L. radiata demonstrates the highest alkaloid diversity (83), with L. aurea (3) and L. longituba (39) showing secondary abundance. Values represent total characterized alkaloids per species. Species names are on the x-axis, and alkaloid content is on the y-axis.

Among the 130 alkaloids identified in Lycoris species, only 7-deoxy-trans-dihydronarciclasine(138) (exclusively found in L. chejuensis) represents a novel discovery, as all others have been documented in previous reviews (Cahlíková et al., 2020). These alkaloids can be categorized into 16 core structural types (Lin et al., 2025), among which the lycorine-type is the most abundant, being found in 26% of all characterized compounds. Galanthamine-type alkaloids have been the most extensively studied because of their clinical use in AD treatment. Notably, hostasinine-type alkaloids are currently represented solely by hostasinine A, which has been identified only in L. albiflora (Jitsuno et al., 2011). Similarly, the galanthindole-type is restricted to lycosprinine B (L. sprengeri) (Wu et al., 2014), and the ismine-type is restricted to ismine (L. squamigera) (Kitajima et al., 2009).

1.3.2 Organ-specific distributions of alkaloids

Plant growth is a dynamic process characterized by stage-dependent expression patterns of secondary metabolites. In medicinal plants, bioactive compounds have distinct organ-specific distributions, as demonstrated by multiple studies. Lycoris species, known for their pharmacologically active alkaloids including galantamine, lycorine, and lycoramine, display significant spatiotemporal variations in secondary metabolite accumulation. These variations have important implications for both plant defense systems and pharmaceutical development. Research has indicated that in Lycoris chinensis (Mu et al., 2010), mature seeds exhibit the highest galantamine content (671.33 µg/g DW), which is 5.2 times greater than that in leaves, while lycorine primarily accumulates in root hairs (505.85 µg/g DW) and lycoramine in seed coats (383.62 µg/g DW). This compartmentalization pattern suggests functional adaptation: elevated alkaloid levels in seeds may provide chemical defense for embryos, whereas root accumulations likely protect against soil pathogens. Notably, the alkaloid content followed a U-shaped developmental pattern, with the highest levels in mature seeds, followed by perennial plants, 1-year-old seedlings, and 3-month-old seedlings, and the lowest in 10-day-old seedlings. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses of L. radiata (Park et al., 2019), further confirmed organ-specific variations. HPLC quantification revealed a ubiquitous galantamine distribution, with concentrations of 0.53 ± 0.07 mg/g DW in roots, 0.27 ± 0.04 mg/g DW in bulbs, and 0.75 ± 0.09 mg/g DW in leaves. Bulb galantamine levels were 1.42- and 2.78-fold higher than those in roots and leaves, respectively, corresponding to upregulated expressions of biosynthetic genes (e.g., LrNNR, LrN4OMT, and LrCYP96T). In contrast, L. longituba (Li et al., 2020) exhibited a maximum galantamine accumulation in roots (976.14 mg/g DW versus 263.51 mg/g DW in bulbs and 61.63 mg/g DW in leaves), accompanied by tissue-specific expressions of pathway genes (root-predominant OMT versus bulb-specific CYP96T1). This interspecies variation underscores the metabolic diversity within the genus, although current studies have yet to fully characterize the organ-specific alkaloid distribution patterns across Lycoris taxa.

1.3.3 Extraction and detection techniques for lycorine alkaloids

Various extraction methods have been employed to isolate Lycoris alkaloids, with solvent extraction using methanol or ethanol remaining the most conventional approach (Song et al., 2014; Naidoo et al., 2021). Currently, the majority of alkaloid studies utilize alcoholic extracts (Zhou et al., 2024), which are frequently combined with auxiliary techniques to improve extraction efficiency and detection sensitivity. For example, methanol-based ultrasound-assisted extraction (using a 1:10 sample-to-solvent ratio with 45 minutes of ultrasonication) coupled with UHPLC – QTOF – MS/MS analysis successfully identified 37 alkaloids, including 16 novel compounds, with detection limits at the nanogram level. Significant interspecific variation in alkaloid profiles were observed among Lycoris species, with L. sprengeri showing the highest alkaloid diversity and concentration, indicating considerable medicinal potential (Sun et al., 2017). In another study L. radiata bulbs were extracted using 70% ethanol, yielding 212 g of extract from 5 kg of raw material (4.24% extraction yield). Subsequent chloroform fractionation resulted in 80.2% enrichment, followed by multistep chromatography (silica gel, RP-18, and Sephadex LH-20) to isolate nine alkaloids (35–98 mg each). Notably, yemenine A (139) was obtained with a yield of 0.00196% (98 mg/5 kg) (Hu et al., 2018). Recent methodological advances integrate ultrasound-assisted extraction with capillary electrophoresis-electrochemiluminescence (CE-ECL), enabling baseline separation of four alkaloids within 16 minutes and achieving detection limits of 1.8–14 ng/mL. Compared with conventional methods, this technique has three distinct advantages: (1) a 46-minute reduction in analysis time, (2) nanogram-level sensitivity, and (3) microliter-scale solvent consumption, thereby establishing an efficient approach for trace alkaloid analyses in complex matrices (Sun et al., 2017). A novel solid-phase extraction (SPE) technique utilizing electrostatic repulsion principles was developed for alkaloid extraction from Lycoris and four related plant species, with subsequent LC – MS analysis. Under optimized acidic conditions (0.1% formic acid, pH 3.0), this method achieved the selective elution of positively charged alkaloids (10% methanol) while retaining nonalkaloid components through hydrophobic interactions (90% methanol). LC – MS analysis successfully identified 42 intact alkaloids, overcoming the structural degradation issues associated with pH fluctuations associated with conventional approaches (Du et al., 2019). These methodological advances establish a robust foundation for the quality control and pharmaceutical development of L. radiata and related species.

1.3.4 Factors influencing alkaloid contents in Lycoris species

The alkaloid contents in Lycoris plants are influenced by multiple interacting factors that collectively determine their medicinal and economic value. Alkaloid accumulations in this genus arise from complex interactions among genetic factors, environmental conditions, and endophytic microbial communities. Comparative analyses demonstrated significant interspecific variation in alkaloid content among Lycoris species, with L. radiata (0.48 mg/g DW) exhibiting substantially higher levels than L. chinensis (0.18 mg/g DW) and other examined species including L. sanguinea, L. squamigera, L. uydoensis, and L. chejuensis (Yeo et al., 2021). In addition to quantitative variations, the alkaloid profiles differ significantly among Lycoris species. UHPLC – QTOF – MS/MS analyses of L. radiata, L. aurea, L. rosea, L. straminea, L. sprengeri, and L. longituba revealed 37 alkaloids. The structural diversity and relative abundance for L. sprengeri were greatest, whereas those of L. straminea were the lowest. Notably, L. radiata and L. aurea accumulate relatively high concentrations of polar alkaloids ( Li et al., 2019), underscoring the pharmaceutical potential of this genus.

Geographical distribution and environmental conditions significantly influence alkaloid accumulation patterns. Intraspecific variations are evident across regions, as shown by L. aurea populations from Jiangxi Quannan containing 6–7 times higher lycorine and galantamine levels than those from Hunan Zhongfang (Table 1). These alkaloid levels are positively correlated with specific soil parameters (Zuo et al., 2025). Despite their pharmacological importance, most alkaloids in wild Lycoris plants are present in trace quantities (<0.1% dry weight for galantamine), which restricts their commercial utilization (Liu et al., 2020). Emerging evidence indicates that Lycoris-endophyte interactions modulate alkaloid biosynthesis through complex regulatory networks (Zhou et al., 2020). Tissue-specific endophytic communities have been characterized across different plant organs (Liu et al., 2020). Endophytic diversity and regulatory functions vary significantly among Lycoris species.L. aurea maintained higher fungal diversity than L. radiata did, with enriched taxa (e.g., Phyllosticta, Colletotrichum, and Acrocalymna) showing positive correlations with galantamine accumulation. Notably, endophytes isolated from L. aurea (e.g., Phyllosticta sp. LaL1, Colletotrichum sp. LaR6, Clonostachys sp. LaR14, and Acrocalymna sp. LaR15) selectively increased galantamine production (but not lycorine production) in L. radiata. These findings demonstrate the cross-species applicability of endophytic inoculants and establish a theoretical foundation for Lycoris microbiome research (Wang et al., 2024).

2 Pharmacological activities of alkaloids from Lycoris species

2.1 Cholinesterase inhibition

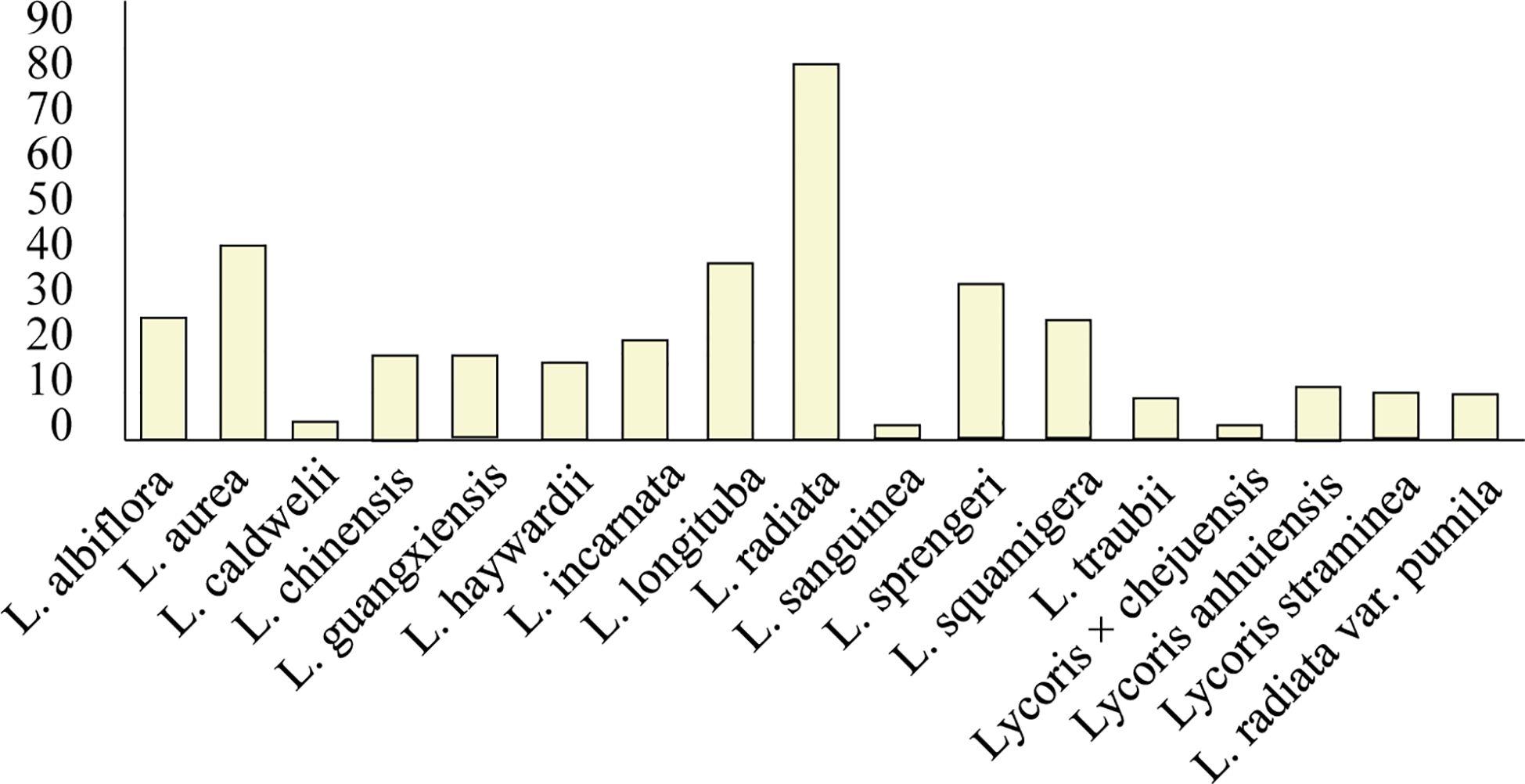

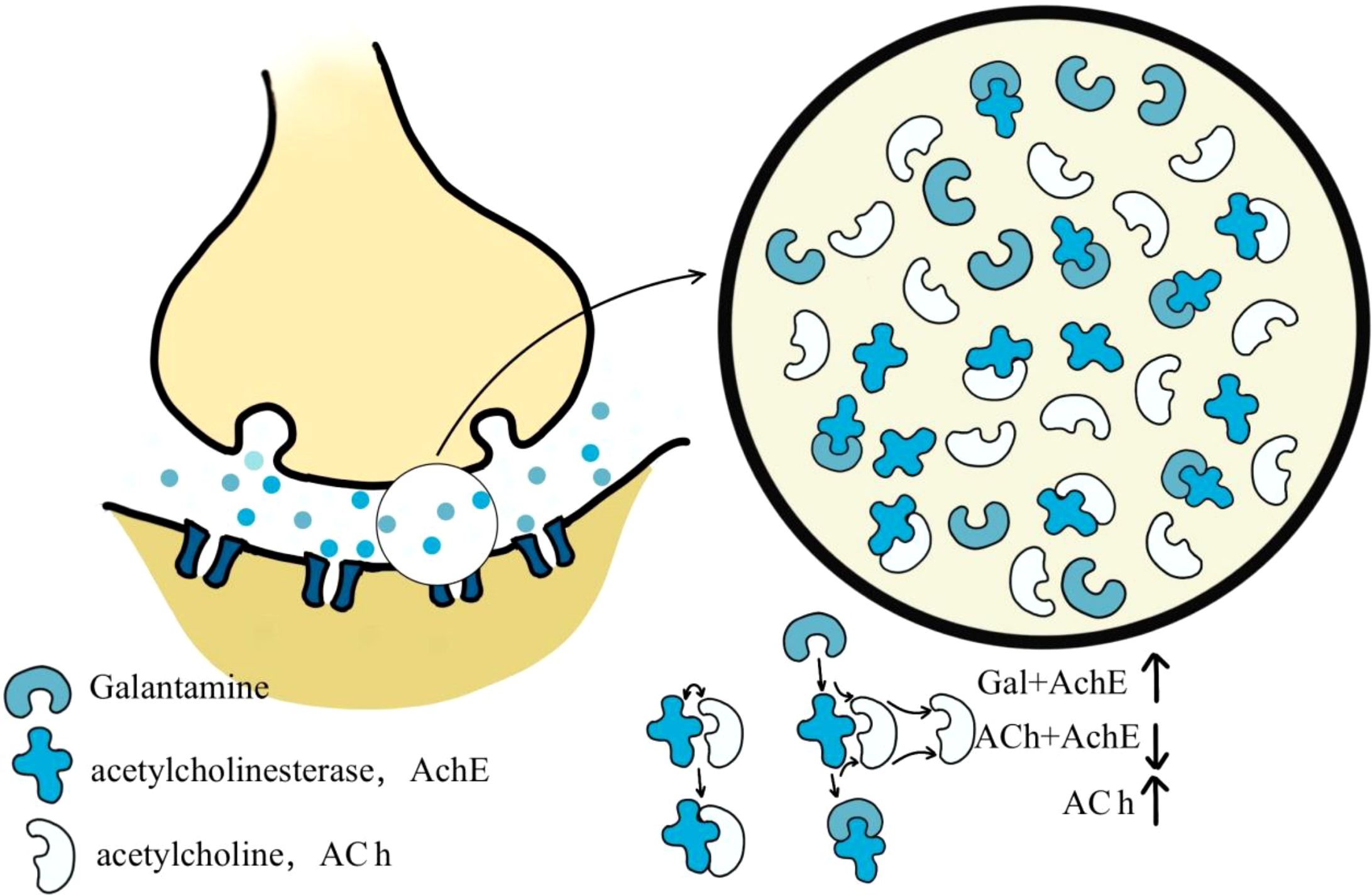

The Lycoris genus is widely recognized for producing galanthamine, a natural alkaloid clinically used to treat AD. With the molecular formula C17H21NO3 (MW: 323.8145), this secondary metabolite isolated from Lycoris plants functions as an approved acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibitor in medical practice (2012) (Figure 4). Galantamine acts as a selective, reversible, and competitive AChE inhibitor (Desgagné-Penix, 2021) (Table 1). Galantamine acts as a selective, reversible, and competitive AChE inhibitor.

Figure 4. Mechanism of action of galanthamine Galantamine is a specific, competitive, and reversible acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor. It competes with acetylcholine (ACh) at the synaptic cleft, preventing the degradation of ACh by inhibiting its binding to acetylcholinesterase.

Lycoramine (dihydrogalantamine, C17H23NO3), initially isolated from Amaryllidaceae bulbs in the 1950s, is another effective AChE inhibitor. This compound has been clinically applied in the treatment of myasthenia gravis and postpolio syndrome (Irwin and Smith, 1960). Recent investigations of Chinese Lycoris species have indicated that the content of lycoramine is approximately 7-fold greater than that of galanthamine (Tang et al., 1964). Preliminary clinical trials in China have shown that compared with galanthamine lycoramine hydrobromide effectively alleviates muscle weakness, albeit with marginally lower efficacy. Importantly, compared with galanthamine (Uyeo and Koizumi, 1953), lycoramine enhances striated muscle contraction through cholinesterase inhibition, resulting in a therapeutic index similar to that of galanthamine, suggesting the potential for expanded clinical use.

2.2 Antiviral activity

Lycorine demonstrates broad-spectrum antiviral activity against diverse viruses. A 2011 Jiangning study reported the effective inhibition of enterovirus 71 (EV71), a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus (Picornaviridae family), by lycorine treatment. This study revealed that lycorine significantly decreased mortality in EV71-infected mice by blocking viral protein synthesis (Liu et al., 2011), indicating its potential utility for managing EV71 outbreaks in Asia. In 2020, Chen et al. reported the inhibitory effect of lycorine on Zika virus (ZIKV). Originally discovered in 1947 during yellow fever surveillance in Uganda’s Zika Forest (Chen et al., 2020), ZIKV infection is clinically associated with Guillain–Barré syndrome, meningitis, and other neurological complications. Their research demonstrated that lycorine effectively suppressed ZIKV replication in vitro through specific inhibition of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), highlighting its therapeutic potential.

Lycorine exhibits antiviral activity against the highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus (Yang et al., 2019). In screening anti-coronaviral alkaloids, pancracine (96), 6β-acetyl-8-hydroxy-9-methoxycrinamine (26), haemanthamine (29), and haemanthidine(30) showed efficacy comparable to that of lycorine in suppressing human coronavirus (HCoV)-OC43 replication (Merindol et al., 2024). Additionally, lycoricidine derivatives from Lycoris radiata extracts demonstrated notable activity against tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), with N-methyl-2,3,4-trimethoxylycoricidine (131) and N-methyl-2-methoxy-3,4-acetonidelycoricidine (132) having the strongest inhibitory effects (Yang et al., 2018).

2.3 Antitumor activity

Lycorine is an isoquinoline alkaloid that is abundant in Amaryllidaceae plant bulbs. It exerts antitumor effects through three main mechanisms: inhibiting tumor cell metastasis, inducing tumor cell apoptosis, and arresting the cell cycle. Studies have shown that lycorine downregulates the key metastatic regulators, MMP-9 and MMP-2 in a dose-dependent manner, thereby suppressing cell migration (Liu et al., 2018). In 2019, Ning et al. demonstrated that lycorine induces reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated activation of the p38 MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) and p53-dependent apoptotic pathways in human osteosarcoma cells, leading to G1 phase arrest without causing organ toxicity (Ning et al., 2020). Lycoreine (55) (C18H23NO4; molecular weight: 317.38), a pyrrole-type alkaloid extracted from Lycoris species (e.g., L. radiata and L. squamigera), shares a common biosynthetic precursor 4’-O-methylnorbelladine with other Lycoris alkaloids (Ding et al., 2017). This compound demonstrates notable cytotoxicity against leukemia and hepatocellular carcinoma cells, showing approximately twofold higher potency than its maximum nontoxic concentration (MNTC) and superior efficacy to homolycorine(49). Its antitumor mechanisms involve inhibition of topoisomerase I, DNA breakage and recombination, and induction of apoptosis (Nair and Van Staden, 2021). Although it enhances chemosensitivity and reduces drug resistance, compared with other Lycoris alkaloids, lycoreine(55) is less effective against hepatic, uterine, and breast cancers (Jia et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2024).

The total alkaloid extracts of L. aurea, L. radiata, and L. guangxiensis significantly inhibited the growth of HepG2 cells, with L. radiata extract showing 84.91% inhibition (Tian et al., 2015a). Notably, (+)-N-methoxylcarbonyl-nandigerine(126) and (+)-N-methoxycarbonyl-lindcarpine(127) isolated from L. caldwellii exhibited potent cytotoxicity against astrocytoma CCF-STTG1 and glioma (e.g., CHG-5, SHG-44, and U251) cell lines, with IC50 values ranging from 9.2 to 12.2 μM (Cao et al., 2013), suggesting therapeutic potential for nervous system tumors. Furthermore, 2-demethyl-isocorydine, (+)-8-hydroxy-homolycorine-α-N-oxide, and isocorydine from L. aurea exhibited potent cytotoxicity against head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) (Cao et al., 2013; Song et al., 2014). These findings highlight the broad anticancer potential of these compounds.

2.4 Anti-inflammatory properties

Pharmacological studies have increasingly demonstrated that alkaloids from Lycoris species possess significant anti-inflammatory activities. In particular, lycorine, galanthamine, and narciclasine have been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (Li et al., 2021). Specifically, lycorine exerts cardioprotective effects through the inhibition of PI3K/AKT and NF-κB-induced inflammatory responses (Tuo et al., 2024), whereas narciclasine functions through the suppression of both the NF-κB and MAPK pathways (Shen et al., 2019). Additionally, 1-hydroxy-ungeremine (137) and N-methoxycarbonyl-2-demethyl-isocorydione (138) isolated from Lycoris radiata markedly inhibited COX-2 (90%), indicating their potential for anti-inflammatory drug development (Liu et al., 2015). Furthermore, 2-demethyl-isocorydine (123), dehydrocrebanine(125), and isocorydine (124) extracted from Lycoris aurea exhibited anti-inflammatory activity with more than 85% inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (Cao et al., 2013).

2.5 Neuroprotective effects

Lycoris alkaloids exhibit neuroprotective activity. Several neuroprotective alkaloids have been isolated and identified from the bulbs of Lycoris aurea. Among these, 2α-hydroxy-6-O-n-butyloduline (38), O-n-butyllycorenine (50), and N-(chloromethyl)lycoramine (16) demonstrated significant protective effects against both CoCl2-induced hypoxic injury and H2O2-induced oxidative damage. Among the known alkaloids, galantamine specifically targeted CoCl2-induced damage, whereas N-demethylgalantamine (9) and lycorinine-type alkaloids were effective in both injury models. The neuroprotective effects of these compounds are achieved mainly by inhibiting neuronal apoptosis and reducing oxidative stress (Jin et al., 2014). Alkaloids isolated from Lycoris sprengeri exhibited protective effects against neuronal damage induced by H2O2 (oxidative damage), CoCl2 (hypoxic damage), and Aβ25-35 (amyloid toxicity). O-methyllycorenine (52) and hippadine (86) significantly protected against H2O2-induced damage, with O-methyllycorenine(52) increasing cell viability from 56.1% to 68.9% at 25 μM (p< 0.01). In response to CoCl2-induced damage, lycosprenine (87), O-methyllycorenine (52), and tortuosine (89) all exhibited notable activity, with lycosprenine (87) increasing viability to 64.2% at 25 μM (control: 51.6%). Notably, 2α-methoxy-6-O-methyllycorinine (54) showed particularly strong protection against Aβ25-35 toxicity, increasing viability to 77.6% at 12.5 μM (control: 59.5%). Structural–activity relationship analysis revealed that methoxylation at the C-2 position significantly enhanced bioactivity. Additionally, the broad effectiveness of lycorinine-type alkaloids across multiple models suggests their potential multitarget mechanisms of action (Wu et al., 2014). Neuroprotective compounds were also isolated from Lycoris radiata. In addition to known neuroprotective alkaloids such as galantamine, three compounds, namely, 2α-methoxy-6-O-ethyloduline (54), O-demethyllycoramine N-oxide (14), and N-chloromethyl ugiminoline (66) demonstrated significant protective effects against both H2O2- and CoCl2-induced cellular damage. N-Chloromethylugiminoline exhibited significant protective effects against Aβ25-35-induced cellular damage. These findings indicate that neuroprotective alkaloids are widely distributed among Lycoris species and that structurally similar alkaloid compounds may have therapeutic potential for related diseases (Li et al., 2013).

2.6 Other pharmacological activities

Lycoris alkaloids exhibit broad medicinal potential with diverse pharmacological activities. Notably, lycorine (80) shows unique efficacy in treating cutaneous fibrotic disorders, particularly refractory hypertrophic scars. Research has demonstrated that lycorine (80) specifically inhibits hypertrophic scar fibroblast (HSF) proliferation while inducing apoptosis, without affecting normal fibroblasts (NFs). The mechanism involves mainly i the suppression of collagen and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression in HSFs, which reduces extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation and consequently regulates HSF metabolism (Dong et al., 2022). These findings indicate that lycorine may serve as a therapeutic agent for hypertrophic scars because of its proapoptotic and antifibrotic effects. However, further studies are needed to fully understand its mechanisms of action and evaluate its clinical safety. Lycoris alkaloids also exhibit antimalarial activities. While lycorenine (55) and haemanthamine (29) have demonstrate weaker effects than artemisinin dose, they specifically target key enzymes in the plasmodial FAS-II biosynthesis pathway (Nair and van Staden, 2019). Their structural complexity provides a valuable basis for developing novel antimalarial agents (Narula et al., 2019). These alkaloids also demonstrate antifungal activities. Studies have shown that methanol extracts from Lycoris radiata significantly inhibit Magnaporthe oryzae mycelial growth, with lycorine (80) and narciclasine (100) likely serving as the main active components (Qiao et al., 2023). Lycorine (80) has been shown to mitigate carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced hepatic fibrosis by modulating the JAK2/STAT3 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways, suggesting its potential therapeutic application for liver injury-related diseases (Y. Tang et al., 2024).

Among the diverse alkaloids identified in Lycoris radiata, galanthamine (13) has demonstrated the most prominent clinical value. As a reversible acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor modulator, this compound has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the clinical treatment of AD (Howes and Houghton, 2003). In contrast, lycorine (80) has a broad exhibits a broader spectrum of pharmacological activities, including antiviral, antitumor, analgesic, hepatoprotective, and anti-inflammatory effects; however, its clinical application remains limited because of its significant cytotoxicity (Su et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). Another alkaloid, lycoramine (18), also possesses AChE inhibitory activity, albeit with lower potency than galanthamine (13) does (Ding et al., 2017; Nair and Van Staden, 2021). Moreover, narciclasine (134) primarily exerts anticancer effects through the induction of apoptosis (Li et al., 2021). In summary, while the use of galanthamine (13) has been well-established for the treatment of neurological disorders, other Lycoris alkaloids show promising potential in oncology and infectious disease management. However, their therapeutic application is currently limited by toxicity concerns, necessitating further structural modifications and research to enhance safety profiles and clinical applicability.

3 Regulatory mechanism and bioengineering of active compounds

The limited availability of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids (AAs) from natural sources presents significant challenges, including their low abundances in plants, high extraction costs, and fragile plant sources with poor regenerative capacities. Furthermore, unsuccessful cultivation attempts and costly isolation techniques further restrict their supply (Sanyal et al., 2023). These factors collectively hinder efforts to meet the growing demand for these valuable medicinal compounds (Shi et al., 2025).

Although significant progress has been made in elucidating key biosynthetic pathways (Desgagné-Penix, 2021), the complete biosynthesis of Lycoris alkaloids remains unclear. Given their limited availability and costly extraction, alternative synthesis methods are being actively explored. Current approaches include biomimetic oxidation and intramolecular Heck reactions using phenol derivatives. Further investigation of Lycoris alkaloid biosynthetic pathways and their regulatory mechanisms could enable sustainable production and facilitate new therapeutic applications.

3.1 Overview of biosynthesis pathways

Alkaloids are valuable secondary metabolites that are widely present in bacteria, fungi, and plants. These compounds not only function in organismal growth (Lam et al., 2022), but also exhibit various biological activities (Kishimoto et al., 2016), contributing significantly to human health. However, the current understanding of their biosynthetic pathways in plants remains limited, particularly in Lycoris radiata, a species renowned for its therapeutic potential against AD. Allium sativum alkaloids, particularly those known for their therapeutic effects against AD, undergo a multistep biosynthetic process involving methylation, reduction, oxidation, condensation, hydroxylation, phenol–phenol coupling, and oxygen bridge formation (Kilgore et al., 2014).

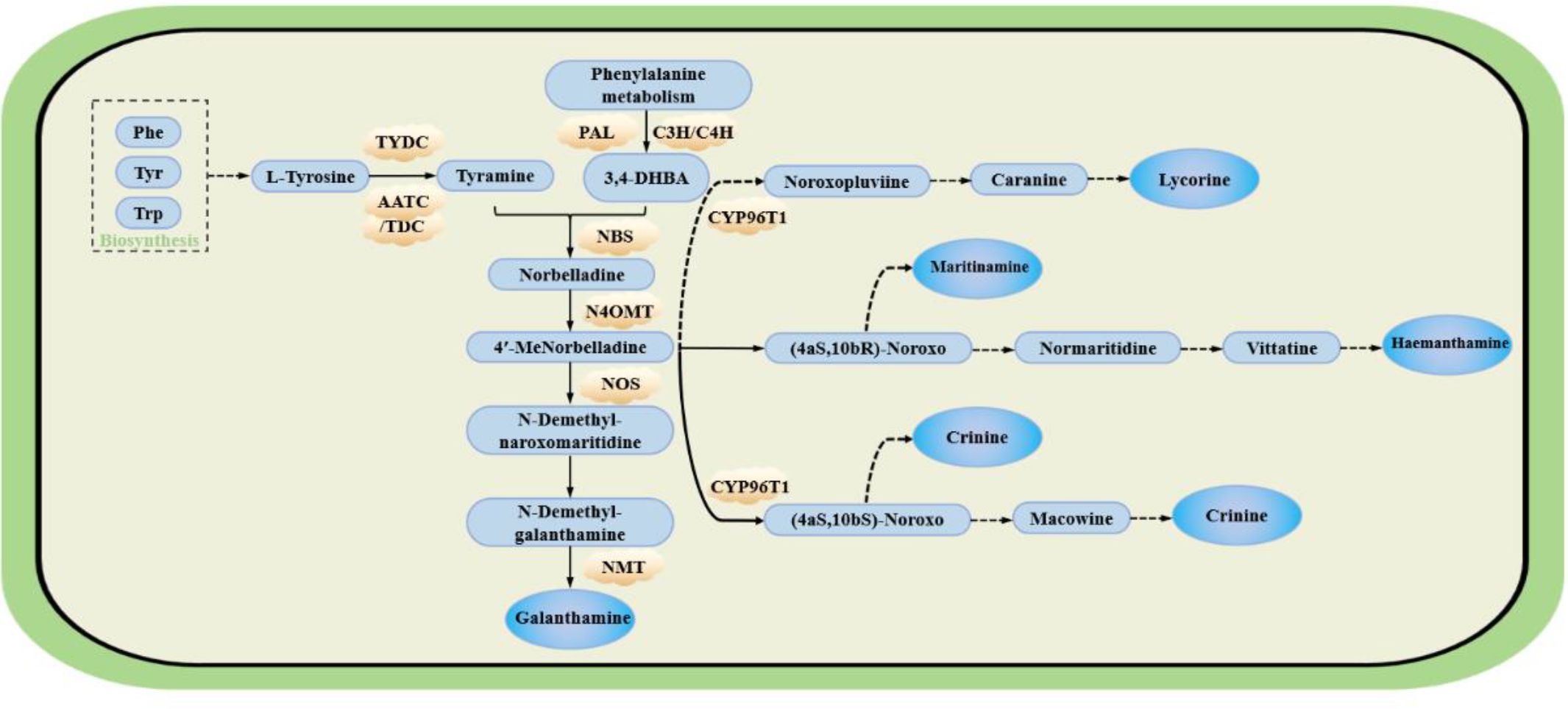

Two amino acids, L-phenylalanine and L-tyrosine, serve as the primary precursors for alkaloid biosynthesis in Allium sativum. Phenylalanine is first converted to trans-cinnamic acid by phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL). Trans-cinnamic acid subsequently undergoes cytochrome P450-mediated two-step hydroxylation to yield 3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde (3,4-DHBA). In parallel, tyrosine decarboxylation is catalysed by tyrosine decarboxylase (TYDC) to produce tyramine. This tyramine then condenses with 3,4-DHBA through the action of norbelladine synthase (NBS) to form norbelladine. Norbelladine is converted to 4′-O-methylnorbelladine by O-methyltransferase (OMT). As a central precursor in the Lycoris alkaloid biosynthesis pathway, 4′-O-methylnorbelladine undergoes cytochrome P450-mediated oxidative C-C phenol coupling reactions. Product analysis revealed three major alkaloid types derived from this intermediate: lycorine-type, galantamine-type, and narciclasine-type alkaloids, as illustrated in Figure 5 (Qingzhu Li et al., 2022).

Figure 5. The possible pathway of main alkaloid synthesis in Lycoraceae [based on (Li et al., 2019) (Hotchandani et al., 2019) (Li et al., 2022)] Phe, phenylalanine; Tyr, tyrosine; Trp, tryptophan; PAL, phenylalanine ammonia lyase; C4H, cinnamate-4-hydroxylase; C3H, cinnamate-3-hydroxylase; TYDC, tyrosine decarboxylase; NBS, norbelladine synthase; CYP96T1, cytochrome P450 family enzyme; AADC, aromatic-L-amino-acid decarboxylase; TDC, L-tryptophan decarboxylase; N4OMT, norbelladine O-methyltransferase; NOS, Noroxomaritidine synthase; NMT, S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine:norgalanthamine N-methyltransferase; 3,4-DHBA, 3,4-Dihydroxybenzaldehyde; 4′-MeNorbelladine, 4’ Methylnorbelladine; (4aS,10bR)-Noroxo, (4aS,10bR)-Noroxomaritidine; (4aS,10bS)-Noroxo, (4aS,10bS)-Noroxomaritidine; Macowine, (4aR,10bS)-Normaritidine. PAL, C3H, C4H, TYDC, CYP96T1, N4OMT, NBS, and NMT have all been studied in Lycoris.

3.2 Functions and regulation of key enzymes

Studies have demonstrated that alkaloid biosynthesis is regulated by multiple factors through complex physiological processes. The identification of norbelladine 4′-O-methyltransferase (N4′OMT) enables future characterization of related enzymes in the Amaryllidaceae alkaloid biosynthetic pathway. Genes coexpressed with NpN4′OMT may serve as candidate genes for subsequent steps in this pathway, particularly given role of N4′OMT in dinucleotide cofactor (NADPH/NADH) binding (Kavanagh et al., 2008; Porté et al., 2013). 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases and cytochrome P450 enzymes exhibit hydroxylation activities, representing promising candidate gene families for hydroxylation steps in Amaryllidaceae (Lester et al., 1997; Nelson and Werck-Reichhart, 2011). Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses of Lycoris radiata were conducted to investigate galantamine biosynthesis across different tissues. The results demonstrated that LrNNR, LrN4OMT, and LrCYP96T exhibited the highest expression levels in bulbs, which correlated with the significantly greater galantamine accumulation observed in bulbs than in roots and leaves (Tang et al., 2023). OMT was identified as the key enzyme mediating substrate- and region-specific polymethylation in galantamine biosynthesis, with additional roles in alkaloid metabolism (Chang et al., 2015; Hawkins and Smolke, 2008). NMT, another methyltransferase, has been demonstrated to catalyse phenylpropanoid alkaloid biosynthesis (Grobe et al., 2011).

SWATH-MS-based quantitative proteomic analysis revealed 720 significantly differentially expressed proteins in L. longituba with high alkaloid contents. These proteins were predominantly enriched in biosynthetic pathways, particularly those involved in amino acid metabolism and starch/sucrose metabolism. Notably, O-methyltransferase (OMT) and N-methyltransferase (NMT) participate directly in the galanthamine biosynthetic pathway (Tang et al., 2023). Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic profiling of Lycoris radiata revealed eight key genes implicated that are involved in galanthamine biosynthesis (including LrPAL2, LrC4H2, and LrN4OMT). Among these genes, LrNNR and LrN4OMT displayed the greatest expression levels in bulb tissues, which concurrently the greatest increase in galanthamine accumulation (0.75 mg/g dry weight) - 1.42-fold and 2.78-fold greater than that in roots and leaves, respectively. These findings strongly support the pivotal role of LrNNR and LrN4OMT in galanthamine production (Park et al., 2019). Furthermore, comprehensive functional characterization of three NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductases (e.g., LrCPR1, LrCPR2, and LrCPR3) in L. radiata was performed. In vitro enzymatic analyses coupled with heterologous yeast expression systems confirmed their capacity to facilitate CYP96T6 activity (a P450 enzyme mediating galanthamine precursor biosynthesis), resulting in significantly elevated yields of N-demethylnarwedine, a crucial biosynthetic intermediate (Wu et al., 2024). Complementary work involving LrOMT cloning and heterologous expression in E. coli established its bifunctional O-methylation capability, offering mechanistic understanding of the structural diversification of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids (Li et al., 2019).

3.3 Functions and regulation of key enzymes

Plants have evolved diverse defense mechanisms to adapt to various natural environments. In Hymenocallis, light quality significantly influences alkaloid accumulations. Specifically, red light decreases GAL, LYC, and LYCM levels, whereas blue light increases their accumulation. Notably, blue light provides optimal conditions for inducing alkaloid production in this species. At the genetic level, blue light treatment significantly altered gene transcription patterns in Hymenocallis, potentially promoting alkaloid accumulation. Key biosynthetic genes including PAL, C4H, and TYDC were notably upregulated under blue light conditions (Qingzhu Li et al., 2022). Compared with fully irrigated controls, drought stress induced a steady increase in coptisine levels. However, unlike other environmental stresses, drought was the only condition that significantly elevated coptisine accumulation in most plants. Notably, under severe drought conditions (Yahyazadeh et al., 2018), t coptisine levels plateaued, suggesting a stress threshold effect that requires further investigation. Additionally, soil physicochemical properties influence coptisine production (Frick et al., 2017). Soil physicochemical properties significantly influence lupin growth. As the soil pH increases, both the QA levels and the seed yields decrease in lupin plants, along with a reduction in protein content (Rodés-Bachs and Van der Fels-Klerx, 2023).

3.4 Impact of alternative splicing on alkaloid synthesis

The pharmacological potential of Lycoris alkaloids has generated significant interest in medical research. However, their biosynthetic pathways remain incompletely understood. These complex metabolic processes are tightly regulated across multiple levels—including transcriptional, translational, and post-translational modifications—to adapt to various developmental stages and environmental changes (Lam et al., 2022). Elucidating alkaloid biosynthesis mechanisms is crucial for understanding the secondary metabolism of Amaryllidaceae and facilitating their sustainable development. Alternative splicing represents a key regulatory mechanism within the complex network controlling plant alkaloid biosynthesis.

Alternative splicing, a key gene regulatory mechanism, controls post-transcriptional mRNA processing (Laloum et al., 2018). This process enables cells to produce multiple protein variants from a limited number of genes (Baralle and Giudice, 2017). The biosynthesis of alkaloids in Lycoris species involves a unique plant metabolic pathway in which developmental stage- and stress-responsive alternative splicing regulates multiple genes (Chang et al., 2015). A study by Carqueijeiro of Catharanthus roseus identified alternative splicing events in a monoterpenoid indole alkaloid (MIA) biosynthesis-related gene, revealing its regulatory roles in both MIA production and plant defense responses (Carqueijeiro et al., 2021). In Ginkgo biloba, alternative splicing was shown to regulate flavonoid and terpenoid biosynthesis pathways (He et al., 2022). This mechanism also plays a crucial role in stress response regulation in woody plants (Chen et al., 2020), potentially providing evolutionary advantages for environmental adaptation (Liu et al., 2022).

3.5 Impact of alternative splicing on alkaloid synthesis

Synthetic biology plays a key role in alkaloid research by elucidating the biosynthetic pathways and regulatory mechanisms of alkaloids in plants. This approach helps reveal their essential functions and potential applications in plant physiological and ecological processes.

Since the synthesis of secondary metabolite alkaloids in plants is inherently limited and yields are low, synthetic biology methods are needed to produce the desired components. The first step in this approach is to select an appropriate host organism (Koirala et al., 2022). After the host is determined, the metabolism of precursors for synthesizing target components can be regulated through gene modulation. These include three main strategies—deleting genes, replacing endogenous enzymes with more active homologues, and overexpressing endogenous metabolic genes—all aimed at regulating the synthesis pathway to achieve higher yields. Gene deletion, replacement of endogenous enzymes with more active homologues, and overexpression of endogenous metabolic genes are three approaches to regulate the metabolism of the host organism. These methods can be used to redirect the synthesis pathways of specific target metabolites, thereby increasing the production of desired compounds. The pathway for a particular target metabolite can be determined using these strategies. The entire process requires step-by-step analysis of the target compounds’ intermediates on the basis of the host’s metabolic regulation. This analysis forms the complete synthetic pathway for the target compound. Ultimately, specific enzymes are screened to carry out each reaction in this pathway, achieving the biosynthesis of the desired products (Ausländer et al., 2017; Kitney and Freemont, 2012).

Compared with other drugs, galanthamine, a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, is relatively less toxic to humans. It is currently the only approved treatment for early-stage AD (Houghton et al., 2006). To date, the chemical synthesis of galanthamine has been explored (Marco-Contelles et al., 2006). However, owing to its complex structure and the low yield of multistep chemical synthesis, the production of galantamine through biosynthesis remains economically challenging. Consequently, plant extraction remains the predominant source of galantamine for medical applications (Takos and Rook, 2013).

4 Conclusion and perspectives

Lycoris species, particularly Lycoris radiata, are rich in structurally diverse Amaryllidaceae alkaloids that display a wide range of pharmacological activities, including antitumor, neuroprotective, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory effects. Among these compounds, galanthamine and lycorine have shown great therapeutic potential, especially in the treatment of AD and various cancers. Despite their medicinal value, the development and utilization of these compounds face multiple limitations that require urgent resolution. One of the most critical challenges is the low natural abundances of key alkaloids. For instance, the extraction of a small amount of galanthamine necessitates several tons of wild Lycoris biomass, leading to serious overharvesting, habitat destruction, and the depletion of wild germplasm resources. This situation highlights the urgent need for strategies that ensure sustainable use, including the conservation of germplasm, ex situ cultivation, and strict regulation of wild collection practices.

In addition to resource constraints, the biosynthetic pathways of many Lycoris alkaloids remain poorly characterized. Although several enzymes such as N4OMT, CYP96T1, and NMT have been identified, the downstream steps and regulatory networks that are involved in alkaloid synthesis are still largely unknown. This lack of comprehensive understanding severely limits the application of synthetic biology and metabolic engineering approaches aimed at improving yields. Furthermore, the spatial and temporal distribution of alkaloid biosynthesis in different tissues and developmental stages has been insufficiently explored, which complicates targeted manipulation strategies.

Biotechnological approaches such as tissue cultures and in vitro production systems offer promising alternatives, but they are still limited by problems such as browning of tissues, low regeneration efficiency, poor accumulation of target metabolites, and high production costs. These technical bottlenecks have prevented large-scale industrial application. Moreover, the pharmacological effects of single compounds versus complex alkaloid mixtures remain poorly understood, and the lack of data on synergistic or antagonistic interactions poses challenges for clinical development and safety assessment.

Current research focuses primarily on the application of galantamine in AD treatment, as it represents the most therapeutically promising alkaloid in Lycoris species. However, the structural complexity of galantamine makes its complete chemical synthesis currently unfeasible. The biosynthetic pathway of galantamine involves five main key steps: precursor synthesis, methylation, phenolic oxidative coupling, reduction and cyclization, and transport and accumulation(Figure 5).

In addition to increasing Lycoris yields, since the alkaloid contents in Lycoris are relatively low, a considerable number of current studies have focused on increasing alkaloid yields. Many studies have shown that there is a complex interaction between endophytes in Lycoris and the synthesis of host alkaloids. Inoculation of Lycoris endophytes can increase the alkaloid contents, and different endophytes are associated with the synthesis of different alkaloids. However, relatively few studies have investigated the types of endophytes and the types of Lycoris inoculated, and further in-depth research is needed. Most existing studies are still at the laboratory stage and lack feasibility studies on large-scale inoculation. In addition to adding inducers, which is an effective method to increase the alkaloid contents in Lycoris, methyl jasmonate is one of them (Wang et al., 2016). To date, several key genes involved in the lycorine alkaloid biosynthesis pathway have been identified. Nevertheless, environmental factors play an equally crucial role in regulating the expression of these genes. Jasmonate ZIM-domain (JAZ) proteins, as core regulators of the jasmonic acid (JA) signaling pathway, participate in multiple biological processes including secondary metabolism (particularly alkaloid biosynthesis), stress responses, and plant growth and development. Previous studies have demonstrated that environmental stimuli such as drought and light exposure can activate alkaloid biosynthetic genes (e.g., TYDC and N4OMT) through the ABA and JA signaling pathways (Sha et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2023). Furthermore, experimental evidence confirms that exogenous JA treatment significantly enhances the production of lycorine-type alkaloids in Amaryllidaceae species (Wang et al., 2019). On the basis of the current research status, compared with simply expanding the planting scale, shifting the research focus to cultivating Lycoris varieties with high alkaloid contents or constructing efficient prokaryotic/eukaryotic overexpression systems has become a more effective strategy to solve the alkaloid production bottleneck for the Lycoris genus. Future research should establish a core germplasm resource bank for multiple species, develop synthetic microbial community inoculation technology, and construct a CRISPR-Cas9-mediated metabolic pathway editing system. Moreover, improving basic research such as endophyte isolation rate data, standardized methyl jasmonate (MeJA) treatment protocols, and optimization of heterologous expression systems, is necessary.

Ethics statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Author contributions

J-XC: Writing – original draft. JZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Y-MC: Writing – review & editing. J-XX: Writing – review & editing. YS: Writing – review & editing. ZY: Writing – review & editing. FY: Writing – review & editing. M-XC: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. YC: Writing – review & editing. Q-ZL: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20240813145916021), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (2025A1515011598), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (25ZR1401315),Shanghai Rising-Star Program, China (No.200B1404100).the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31801889, 32002067), and the STI 2030-Major Projects (No.2023ZD0405602).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Prof. Yong-Chun Zhang and Prof. Liu-Yan Yang for their valuable guidance and constructive suggestions during the revision of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1639654/full#supplementary-material

References

Ausländer, S., Ausländer, D., and Fussenegger, M. (2017). Synthetic biology-the synthesis of biology. Angew Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 56, 6396–6419. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609229

(2012). In liverTox: clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury (Bethesda (MD: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases).

Baralle, F. E. and Giudice, J. (2017). Alternative splicing as a regulator of development and tissue identity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 437–451. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.27

Cahlíková, L., Breiterová, K., and Opletal, L. (2020). Chemistry and biological activity of alkaloids from the genus lycoris (Amaryllidaceae). Molecules 25. doi: 10.3390/molecules25204797

Cao, P., Pan, D.-S., Han, S., Yu, C.-Y., Zhao, Q.-J., Song, Y., et al. (2013). Alkaloids from Lycoris caldwellii and their particular cytotoxicities against the astrocytoma and glioma cell lines. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 36, 927–932. doi: 10.1007/s12272-013-0089-3

Carqueijeiro, I., Koudounas, K., Dugé de Bernonville, T., Sepúlveda, L. J., Mosquera, A., Bomzan, D. P., et al. (2021). Alternative splicing creates a pseudo-strictosidine β-d-glucosidase modulating alkaloid synthesis in Catharanthus roseus. Plant Physiol. 185, 836–856. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiaa075

Chang, X. (2015). Lycoris, the basis of the galanthamine industry in China. Res. Rev. J. Agric. Allied Sci. 4, 1–8. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01240

Chang, L., Hagel, J. M., and Facchini, P. J. (2015). Isolation and characterization of O-methyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of glaucine in glaucium flavum. Plant Physiol. 169, 1127–1140. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01240

Chen, H., Lao, Z., Xu, J., Li, Z., Long, H., Li, D., et al. (2020). Antiviral activity of lycorine against Zika virus in vivo and in vitro. Virology 546, 88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2020.04.009

Chen, G. L., Tian, Y. Q., Wu, J. L., Li, N., and Guo, M. Q. (2016). Antiproliferative activities of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids from Lycoris radiata targeting DNA topoisomerase I. Sci. Rep. 6, 38284. doi: 10.1038/srep38284

Chen, M. X., Zhang, K. L., Zhang, M., Das, D., Fang, Y. M., Dai, L., et al. (2020). Alternative splicing and its regulatory role in woody plants. Tree Physiol. 40, 1475–1486. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpaa076

Chen, Y., Leng, Y. N., and Zhu, F. Y. (2023). Water-saving techniques: physiological responses and regulatory mechanisms of crops. Adv. Biotechnol. 1, 3.

Desgagné-Penix, I. (2021). Biosynthesis of alkaloids in Amaryllidaceae plants: a review. Phytochem. Rev. 20, 409–431. doi: 10.1007/s11101-020-09678-5

Ding, Y., Qu, D., Zhang, K. M., Cang, X. X., Kou, Z. N., Xiao, W., et al. (2017). Phytochemical and biological investigations of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids: a review. J. Asian Nat. Prod Res. 19, 53–100. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2016.1198332

Dong, Y., Lv, D., Zhao, Z., Xu, Z., Hu, Z., and Tang, B. (2022). Lycorine inhibits hypertrophic scar formation by inducing ROS-mediated apoptosis. Front. Bioeng Biotechnol. 10. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.892015

Du, N., Si, W., Liu, Y., Guo, Z., Zhou, W., Zhou, H., et al. (2019). Strong electrostatic repulsive interaction used for fast and effective alkaloid enrichment from plants. J. Chromatogr B Analyt Technol. BioMed. Life Sci. 1105, 148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.12.024

Fennell, C. W. and van Staden, J. (2001). Crinum species in traditional and modern medicine. J. Ethnopharmacology 78, 15–26. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00305-1

Frick, K. M., Kamphuis, L. G., Siddique, K. H., Singh, K. B., and Foley, R. C. (2017). Quinolizidine alkaloid biosynthesis in lupins and prospects for grain quality improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00087

Georgiev, B., Sidjimova, B., and Berkov, S. (2024). Phytochemical and cytotoxic aspects of amaryllidaceae alkaloids in galanthus species: A review. Plants (Basel) 13. doi: 10.3390/plants13243577

Grobe, N., Ren, X., Kutchan, T. M., and Zenk, M. H. (2011). An (R)-specific N-methyltransferase involved in human morphine biosynthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 506, 42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.11.010

Guo, J., Wang, Z., Liu, R., Huang, Y., Zhang, N., and Zhang, R. (2020). Memantine, Donepezil, or Combination Therapy-What is the best therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease? A Network Meta-Analysis. Brain Behav. 10, e01831. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1831

Hafiz, R., Alajlani, L., Ali, A., Algarni, G. A., Aljurfi, H., Alammar, O. A. M., et al. (2023). The latest advances in the diagnosis and treatment of dementia. Cureus 15, e50522. doi: 10.7759/cureus.50522

Hao, B., Shen, S.-F., and Zhao, Q.-J. (2013). Cytotoxic and antimalarial amaryllidaceae alkaloids from the bulbs of lycoris radiata. Molecules 18, 2458–2468. doi: 10.3390/molecules18032458

Hawkins, K. M. and Smolke, C. D. (2008). Production of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 564–573. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.105

He, B., Han, X., Liu, H., Bu, M., Cui, P., and Xu, L. A. (2022). Deciphering alternative splicing patterns in multiple tissues of Ginkgo biloba important secondary metabolites. Ind. Crops Products 181, 114812. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.114812

Hotchandani, T., de Villers, J., and Desgagné-Penix, I. (2019). Developmental regulation of the expression of amaryllidaceae alkaloid biosynthetic genes in narcissus papyraceus. Genes (Basel) 10. doi: 10.3390/genes10080594

Houghton, P. J., Ren, Y., and Howes, M. J. (2006). Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from plants and fungi. Nat. Prod Rep. 23, 181–199. doi: 10.1039/b508966m

Howes, M. J. and Houghton, P. J. (2003). Plants used in Chinese and Indian traditional medicine for improvement of memory and cognitive function. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 75, 513–527. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00128-x

Hu, J., Liu, Y., Li, Q., Zhang, L. F., Jing, N. H., Shi, J. Y., et al. (2018). Amaryllidaceae alkaloids from Lycoris radiata. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 43, 2086–2090. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20180115.016

Huang, S. D., Zhang, Y., He, H. P., Li, S. F., Tang, G. H., Chen, D. Z., et al. (2013). A new Amaryllidaceae alkaloid from the bulbs of Lycoris radiata. Chin. J. Natural Medicines 11, 406–410. doi: 10.1016/s1875-5364(13)60060-6

Irwin, R. L. and Smith, H. J., 3rd (1960). Cholinesterase inhibition by galanthamine and lycoramine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 3, 147–148. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(60)90030-7

Jia, Z. C., Yang, X., Wu, Y. K., Li, M., Das, D., Chen, M. X., et al. (2024). The art of finding the right drug target: emerging methods and strategies. Pharmacol Rev. 76, 896–914.doi: 10.1124/pharmrev.123.001028

Jin, A., Li, X., Zhu, Y.-Y., Yu, H.-Y., Pi, H.-F., Zhang, P., et al. (2014). Four new compounds from the bulbs of Lycoris aurea with neuroprotective effects against CoCl2 and H2O2-induced SH-SY5Y cell injuries. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 37, 315–323. doi: 10.1007/s12272-013-0188-1

Jin, Z. and Yao, G. (2019). Amaryllidaceae and sceletium alkaloids. Nat. Prod Rep. 36, 1462–1488. doi: 10.1039/c8np00055g

Jitsuno, M., Yokosuka, A., Hashimoto, K., Amano, O., Sakagami, H., and Mimaki, Y. (2011). Chemical Constituents of Lycoris albiflora and their Cytotoxic Activities. Natural Product Commun. 6, 1934578X1100600208–1101934578X1100600208. doi: 10.1177/1934578x1100600208

Kandiah, N., Pai, M.-C., Senanarong, V., Looi, I., Ampil, E., Park, K. W., et al. (2017). Rivastigmine: the advantages of dual inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase and its role in subcortical vascular dementia and Parkinson’s disease dementia. Clin. Interventions Aging Volume 12, 697–707. doi: 10.2147/cia.S129145

Kavanagh, K. L., Jörnvall, H., Persson, B., and Oppermann, U. (2008). Medium- and short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase gene and protein families: the SDR superfamily: functional and structural diversity within a family of metabolic and regulatory enzymes. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3895–3906. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8588-y

Kilgore, M. B., Augustin, M. M., Starks, C. M., O’Neil-Johnson, M., May, G. D., Crow, J. A., et al. (2014). Cloning and characterization of a norbelladine 4’-O-methyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of the Alzheimer’s drug galanthamine in Narcissus sp. aff. pseudonarcissus. PloS One 9, e103223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103223

Kishimoto, S., Sato, M., Tsunematsu, Y., and Watanabe, K. (2016). Evaluation of biosynthetic pathway and engineered biosynthesis of alkaloids. Molecules 21. doi: 10.3390/molecules21081078

Kitajima, M., Kinoshita, E., and Kogure, N. (2009). Two new alkaloids from bulbs of lycoris squamigera. Heterocycles: Int. J. Rev. Commun. Heterocyclic Chem. 77, 1389–1396. doi: 10.3987/COM-08-S(F)92

Kitney, R. and Freemont, P. (2012). Synthetic biology - the state of play. FEBS Lett. 586, 2029–2036. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.002

Koirala, M., Karimzadegan, V., Liyanage, N. S., Mérindol, N., and Desgagné-Penix, I. (2022). Biotechnological approaches to optimize the production of amaryllidaceae alkaloids. Biomolecules 12. doi: 10.3390/biom12070893

Laloum, T., Martín, G., and Duque, P. (2018). Alternative splicing control of abiotic stress responses. Trends Plant Sci. 23, 140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.09.019

Lam, P. Y., Wang, L., Lo, C., and Zhu, F. Y. (2022). Alternative splicing and its roles in plant metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23. doi: 10.3390/ijms23137355

Lester, D. R., Ross, J. J., Davies, P. J., and Reid, J. B. (1997). Mendel’s stem length gene (Le) encodes a gibberellin 3 beta-hydroxylase. Plant Cell 9, 1435–1443. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.8.1435

Li, A., Du, Z., Liao, M., Feng, Y., Ruan, H., and Jiang, H. (2019). Discovery and characterisation of lycorine-type alkaloids in Lycoris spp. (Amaryllidaceae) using UHPLC-QTOF-MS. Phytochem. Anal. 30, 268–277. doi: 10.1002/pca.2811

Li, R. W., Palit, P., Smith, P. N., and Lin, G. D. (2021). “Amaryllidaceae alkaloids as anti-inflammatory agents targeting cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: mechanisms and prospects,” in Evidence based validation of traditional medicines: A comprehensive approach. Eds. Mandal, S. C., Chakraborty, R., and Sen, S. (Springer Singapore, Singapore), 97–116.

Li, W., Qiao, C., Pang, J., Zhang, G., and Luo, Y. (2019). The versatile O-methyltransferase LrOMT catalyzes multiple O-methylation reactions in amaryllidaceae alkaloids biosynthesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 141, 680–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.011

Li, Q., Xu, J., Yang, L., Sun, Y., Zhou, X., Zheng, Y., et al. (2022). LED light quality affect growth, alkaloids contents, and expressions of amaryllidaceae alkaloids biosynthetic pathway genes in lycoris longituba. J. Plant Growth Regul. 41, 257–270. doi: 10.1007/s00344-021-10298-2

Li, Q., Xu, J., Yang, L., Zhou, X., Cai, Y., and Zhang, Y. (2020). Transcriptome analysis of different tissues reveals key genes associated with galanthamine biosynthesis in lycoris longituba. Front. Plant Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.519752

Li, X., Yu, H. Y., Wang, Z. Y., Pi, H. F., Zhang, P., and Ruan, H. L. (2013). Neuroprotective compounds from the bulbs of Lycoris radiata. Fitoterapia 88, 82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2013.05.006

Liao, N., Ao, M., Zhang, P., and Yu, L. (2012). Extracts of lycoris aurea induce apoptosis in murine sarcoma S180 cells. Molecules 17, 3723–3735. doi: 10.3390/molecules17043723

Lin, G. D., Vishwakarma, P., Smith, P. N., and Li, R. W. (2025). The occurrence and bioactivities of amaryllidaceae alkaloids from plants: A taxonomy-guided genera-wide review. Plants 14. doi: 10.3390/plants14131935

Liu, X. X., Guo, Q. H., Xu, W. B., Liu, P., and Yan, K. (2022). Rapid regulation of alternative splicing in response to environmental stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.832177

Liu, Z. M., Huang, X. Y., Cui, M. R., Zhang, X. D., Chen, Z., Yang, B. S., et al. (2015). Amaryllidaceae alkaloids from the bulbs of Lycoris radiata with cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory activities. Fitoterapia 101, 188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2015.01.003

Liu, J., Yang, Y., Xu, Y., Ma, C., Qin, C., and Zhang, L. (2011). Lycorine reduces mortality of human enterovirus 71-infected mice by inhibiting virus replication. Virol. J. 8, 483. doi: 10.1186/1743-422x-8-483

Liu, W., Zhang, Q., Tang, Q., Hu, C., Huang, J., Liu, Y., et al. (2018). Lycorine inhibits cell proliferation and migration by inhibiting ROCK1/cofilin−induced actin dynamics in HepG2 hepatoblastoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 40, 2298–2306. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6609

Liu, Z., Zhou, J., Li, Y., Wen, J., and Wang, R. (2020). Bacterial endophytes from Lycoris radiata promote the accumulation of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. Microbiol. Res. 239, 126501. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2020.126501

Lv, Y., Huang, Y., Zhang, P., and Gao, Y. (2023). Maternal dominance of intergeneric hybridization between Lycoris and Clivia. Scientia Hortic. 319, 112132. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112132

Marco-Contelles, J., do Carmo Carreiras, M., Rodríguez, C., Villarroya, M., and García, A. G. (2006). Synthesis and pharmacology of galantamine. Chem. Rev. 106, 116–133. doi: 10.1021/cr040415t

Marucci, G., Buccioni, M., Ben, D. D., Lambertucci, C., Volpini, R., and Amenta, F. (2021). Efficacy of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology 190, 108352. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108352

Merindol, N., Belem Martins, L. L., Elfayres, G., Custeau, A., Berthoux, L., Evidente, A., et al. (2024). Amaryllidaceae alkaloids screen unveils potent anticoronaviral compounds and associated structural determinants. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 7, 3527–3539. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.4c00424

Metz, C. N. and Pavlov, V. A. (2021). Treating disorders across the lifespan by modulating cholinergic signaling with galantamine. J. Neurochem. 158, 1359–1380. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15243

Mu, H. M., Wang, R., Li, X. D., Jiang, Y. M., Peng, F., and Xia, B. (2010). Alkaloid accumulation in different parts and ages of Lycoris chinensis. Z Naturforsch. C J. Biosci. 65, 458–462. doi: 10.1515/znc-2010-7-807

Nair, J. J. and van Staden, J. (2019). The Amaryllidaceae as a source of antiplasmodial crinane alkaloid constituents. Fitoterapia 134, 305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2019.02.009

Nair, J. J. and Van Staden, J. (2021). The plant family Amaryllidaceae as a source of cytotoxic homolycorine alkaloid principles. South Afr. J. Bot. 136, 157–174. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2020.07.013

Narula, A. K., Azad, C. S., and Nainwal, L. M. (2019). New dimensions in the field of antimalarial research against malaria resurgence. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 181, 111353. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.05.043

Nelson, D. and Werck-Reichhart, D. (2011). A P450-centric view of plant evolution. Plant J. 66, 194–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04529.x

Ning, L., Wan, S., Jie, Z., Xie, Z., Li, X., Pan, X., et al. (2020). Lycorine induces apoptosis and G1 phase arrest through ROS/p38 MAPK signaling pathway in human osteosarcoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 45, E126–e139. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000003217

Park, C. H., Yeo, H. J., Park, Y. E., Baek, S. A., Kim, J. K., and Park, S. U. (2019). Transcriptome analysis and metabolic profiling of lycoris radiata. Biol. (Basel) 8. doi: 10.3390/biology8030063

Ping-sheng, H., Kurita, S., Yu, Z., and Lin, J.-Z. (1994). Synopsis of the genus lycoris (Amaryllidaceae) SIDA, Contributions to Botany, 301–331.

Porté, S., Xavier Ruiz, F., Giménez, J., Molist, I., Alvarez, S., Domínguez, M., et al. (2013). Aldo-keto reductases in retinoid metabolism: search for substrate specificity and inhibitor selectivity. Chem. Biol. Interact. 202, 186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2012.11.014

Qiao, S., Yao, J., Wang, Q., Li, L., Wang, B., Feng, X., et al. (2023). Antifungal effects of amaryllidaceous alkaloids from bulbs of Lycoris spp. against Magnaporthe oryzae. Pest Manag Sci. 79, 2423–2432. doi: 10.1002/ps.7420

Quan, M., Jiang, X., Xiao, L., Li, J., Liang, J., and Liu, G. (2024). Reciprocal natural hybridization between Lycoris aurea and Lycoris radiata (Amaryllidaceae) identified by morphological, karyotypic and chloroplast genomic data. BMC Plant Biol. 24, 14. doi: 10.1186/s12870-023-04681-2

Reilly, S., Dhaliwal, S., Arshad, U., Macerollo, A., Husain, N., and Costa, A. D. (2023). The effects of rivastigmine on neuropsychiatric symptoms in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Eur. J. Neurol. 31. doi: 10.1111/ene.16142

Ren, Z., Lin, Y., Lv, X., Zhang, J., Zhang, D., Gao, C., et al. (2021). Clonal bulblet regeneration and endophytic communities profiling of Lycoris sprengeri, an economically valuable bulbous plant of pharmaceutical and ornamental value. Scientia Hortic. 279, 109856. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109856

Ren, Z. M., Zhang, D., Jiao, C., Li, D. Q., Wu, Y., Wang, X. Y., et al. (2022). Comparative transcriptome and metabolome analyses identified the mode of sucrose degradation as a metabolic marker for early vegetative propagation in bulbs of Lycoris. Plant J. 112, 115–134. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15935

Rodés-Bachs, C. and Van der Fels-Klerx, H. J. (2023). Impact of environmental factors on the presence of quinolizidine alkaloids in lupins: a review. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo Risk Assess. 40, 757–769. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2023.2217273

Rong, X., Jiang, L., Qu, M., Hassan, S. S., and Liu, Z. (2021). Enhancing therapeutic efficacy of donepezil by combined therapy: A comprehensive review. Curr. Pharm. Design 27, 332–344. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666201023144836

Sanyal, R., Pandey, S., Nandi, S., Biswas, P., Dewanjee, S., and Shekhawat, M. S. (2023). Biotechnological interventions and production of galanthamine in Crinum spp. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 107, 2155–2167. doi: 10.1007/s00253-023-12444-0

Sha, S., Cai, G., and Liu, S. (2024). Roots to the rescue: how plants harness hydraulic redistribution to survive drought across contrasting soil textures. Adv. Biotechnol. 2, 43. doi: 10.1007/s44307-024-00050-8

Shen, C. Y., Xu, X. L., Yang, L. J., and Jiang, J. G. (2019). Identification of narciclasine from Lycoris radiata (L’Her.) Herb. and its inhibitory effect on LPS-induced inflammatory responses in macrophages. Food Chem. Toxicol. 125, 605–613. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.02.003

Shi, J., Zhang, C., Deng, R., Fernie, A. R., Chen, M., and Zhang, Y.(2025). The biosynthesis and diversity of taxanes: From pathway elucidation to engineering and synthetic biology. Plant Commun. 6, 101460. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2025.101460

Song, J.-H., Zhang, L., and Song, Y. (2014). Alkaloids from Lycoris aurea and their cytotoxicities against the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Fitoterapia 95, 121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.03.006

Su, J., Yin, W., Huo, M., Yao, Q., and Ding, L. (2023). Induction of apoptosis in glioma cells by lycorine via reactive oxygen species generation and regulation of NF-κB pathways. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 396, 1247–1255. doi: 10.1007/s00210-023-02384-x

Sun, S., Wei, Y., Cao, Y., and Deng, B. (2017). Simultaneous electrochemiluminescence determination of galanthamine, homolycorine, lycorenine, and tazettine in Lycoris radiata by capillary electrophoresis with ultrasonic-assisted extraction. J. Chromatogr B Analyt Technol. BioMed. Life Sci. 1055-1056, 15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.04.020

Szlávik, L., Gyuris, Á., Minárovits, J., Forgo, P., Molnár, J., and Hohmann, J. (2004). Alkaloids from Leucojum vernum and antiretroviral activity of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. Planta Med. 70, 871–873. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-827239

Tae, G.-H. and Go, S.-C. (1995). A taxonomic study of the genus Lycoris (Amaryllidaceae) based on morphological characters. Korean Journal of Plant Taxonomy 25, 237–254.

Tae, K. H. and Ko, S. C. (1993). New taxa of the genus Lycoris. Korean J. Plant Taxonomy 23, 233–241. doi: 10.11110/kjpt.1993.23.4.233

Takos, A. M. and Rook, F. (2013). Towards a molecular understanding of the biosynthesis of amaryllidaceae alkaloids in support of their expanding medical use. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 11713–11741. doi: 10.3390/ijms140611713

Tang, X. C., Kin, K. C., and Hsu, B. (1964). Some pharmacologic actions of lycoramine. Sheng Li Xue Bao 27, 335–342.

Tang, M., Li, C., Zhang, C., Cai, Y., Zhang, Y., Yang, L., et al. (2023). SWATH-MS-based proteomics reveals the regulatory metabolism of amaryllidaceae alkaloids in three lycoris species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24. doi: 10.3390/ijms24054495

Tang, Y., Zhu, Z., Li, M., Gao, L., Wu, X., Chen, J., et al. (2024). Lycorine relieves the CCl(4)-induced liver fibrosis mainly via the JAK2/STAT3 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 489, 117017. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2024.117017

Tian, Y., Zhang, C., and Guo, M. (2015a). Comparative analysis of amaryllidaceae alkaloids from three lycoris species. Molecules 20, 21854–21869. doi: 10.3390/molecules201219806

Toriizuka, Y., Kinoshita, E., Kogure, N., Kitajima, M., Ishiyama, A., Otoguro, K., et al. (2008). New lycorine-type alkaloid from Lycoris traubii and evaluation of antitrypanosomal and antimalarial activities of lycorine derivatives. Bioorg Med. Chem. 16, 10182–10189. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.061

Tuo, P., Zhao, R., Li, N., Yan, S., Yang, G., Wang, C., et al. (2024). Lycorine inhibits Ang II-induced heart remodeling and inflammation by suppressing the PI3K-AKT/NF-κB pathway. Phytomedicine 128, 155464. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155464

Uyeo, S. and Koizumi, J. (1953). Lycoris alkaloids, XXV. Studies on the constitution of lycoramine. Pharm. Bull. 1, 202–208. doi: 10.1248/cpb1953.1.202

Wang, R., Han, X., Xu, S., Xia, B., Jiang, Y., Xue, Y., et al. (2019). Cloning and characterization of a tyrosine decarboxylase involved in the biosynthesis of galanthamine in Lycoris aurea. Peerj 7, e6729. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6729

Wang, R., Xu, S., Wang, N., Xia, B., Jiang, Y., and Wang, R. (2016). Transcriptome analysis of secondary metabolism pathway, transcription factors, and transporters in response to methyl jasmonate in lycoris aurea. Front. Plant Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01971

Wang, Z., Yuan, J., Wang, R., Xu, S., and Zhou, J. (2024). Distinct fungal communities affecting opposite galanthamine accumulation patterns in two Lycoris species. Microbiol. Res. 286, 127791. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2024.127791

Wu, Y., Zhang, Y., Fan, H., Gao, J., Shen, S., Jia, J., et al. (2024). Multiple NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductases from Lycoris radiata involved in Amaryllidaceae alkaloids biosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 114, 120. doi: 10.1007/s11103-024-01516-y

Wu, W. M., Zhu, Y. Y., Li, H. R., Yu, H. Y., Zhang, P., Pi, H. F., et al. (2014). Two new alkaloids from the bulbs of Lycoris sprengeri. J. Asian Nat. Prod Res. 16, 192–199. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2013.864639

Yahyazadeh, M., Meinen, R., Hänsch, R., Abouzeid, S., and Selmar, D. (2018). Impact of drought and salt stress on the biosynthesis of alkaloids in Chelidonium majus L. Phytochemistry 152, 204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.05.007

Yang, D. Q., Chen, Z. R., Chen, D. Z., Hao, X. J., and Li, S. L. (2018). Anti-TMV effects of amaryllidaceae alkaloids isolated from the bulbs of lycoris radiata and lycoricidine derivatives. Nat. Prod Bioprospect 8, 189–197. doi: 10.1007/s13659-018-0163-0

Yang, L., Zhang, J. H., Zhang, X. L., Lao, G. J., Su, G. M., Wang, L., et al. (2019). Tandem mass tag-based quantitative proteomic analysis of lycorine treatment in highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus infection. Peerj 7, e7697. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7697

Yang, X., Li, M., Jia, Z. C., Liu, Y., Wu, S. F., Chen, M. X., et al. (2024). Unraveling the Secrets: Evolution of Resistance Mediated by Membrane Proteins. Drug Resist. Update. 101140. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2024.101140

Yeo, H. J., Kim, Y. J., Nguyen, B. V., Park, Y. E., Park, C. H., Kim, H. H., et al. (2021). Comparison of secondary metabolite contents and metabolic profiles of six lycoris species. Horticulturae 7. doi: 10.3390/horticulturae7010005

Zhang, S. Y., Huang, Y., Zhang, P., Zhu, K. R., Chen, Y. B., and Shao, J. W. (2021). Lycoris wulingensis, a dwarf new species of Amaryllidaceae from Hunan, China. PhytoKeys 177, 1–9. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.177.62741

Zhang, K., Wang, X., Chen, X., Zhang, R., Guo, J., Wang, Q., et al. (2024). Establishment of a homologous silencing system with intact-plant infiltration and minimized operation for studying gene function in herbaceous peonies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25. doi: 10.3390/ijms25084412

Zhang, F., Wang, T., Shu, X., Wang, N., Zhuang, W., and Wang, Z. (2020). Complete Chloroplast Genomes and Comparative Analyses of L. chinensis, L. anhuiensis and L. aurea (Amaryllidaceae). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21. doi: 10.3390/ijms21165729

Zhao, H., Chen, Y., Qian, L., Du, L., Wu, X., Tian, Y., et al. (2023). Lycorine protects against septic myocardial injury by activating AMPK-related pathways. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 197, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2023.01.010