- Department of Biology, Changwon National University, Changwon, Republic of Korea

Introduction: The genus Salix, widely distributed across the Northern Hemisphere, is characterized by its dioecious nature and frequent natural hybridization. It has significant ecological and economic value in landscaping, ornamentation purposes, biomass production, and traditional medicine. Understanding its evolutionary dynamics is crucial for effective conservation and sustainable utilization. While hybridization and intracellular gene transfer offer valuable insights into its genetic architecture and evolutionary trajectories, studies examining both chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes remain limited.

Methods: We sequenced and assembled the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of male and female individuals from three closely related Salix species, namely S. pierotii, S. babylonica, and S. pseudolasiogyne, and incorporated data from eight additional Salix species for comparative analysis. Phylogenetic relationships were reconstructed and divergence times were estimated to elucidate the evolutionary history.

Results: The chloroplast genomes ranged from 155,688 to 155,695 bp, and the mitochondrial genomes from 705,072 to 705,179 bp, both showing similar proportions of repetitive sequences. Phylogenetic analyses revealed two main clades corresponding to the Salix and Vetrix subgenera, with an estimated divergence time of approximately 25–26 MYA. Discrepancies between chloroplast- and mitochondrial-based phylogenies suggest distinct evolutionary histories, and certain mitochondrial genes showed stronger positive selection than chloroplast genes. Homologous fragments between the two organelle genomes indicate intracellular gene transfer events.

Discussion: The observed alternation between S. pierotii and S. pseudolasiogyne in the mitochondrial phylogeny may indicate potential gene flow or introgressive hybridization, providing further evidence of complex genomic interactions underlying the diversification of Salix. Overall, this study underscores the importance of mitochondrial genome analysis in revealing organelle genome evolution and its role in shaping genetic diversity and evolutionary dynamics within Salix.

1 Introduction

Chloroplasts and mitochondria likely originated from independent prokaryotic organisms that once lived freely. The endosymbiotic theory states that chloroplasts and mitochondria were engulfed by an ancestral eukaryotic cell, and they gradually transferred most of their genetic material to the nucleus of the host cell over time, eventually evolving into organelles with essential roles in eukaryotic cells (Mereschkowsky, 1905; Wallin, 1927; Gray, 1992; Ku et al., 2015). Despite partial gene transfer to the host nucleus, both organelles maintain intricate communication with the nuclear genome and play key roles in cellular metabolism (Chang et al., 2011; Gray, 2012). In angiosperms, chloroplast genomes are generally conserved in size (120–160 kb) and structurally stable, whereas mitochondrial genomes are larger and more variable (200–800 kb) (Palmer, 1983; Wicke et al., 2011; Daniell et al., 2016; Gualberto et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2016). Inheritance of chloroplasts is predominantly maternal, although biparental or paternal inheritance can occur in some species (Hu et al., 2008; Sakamoto and Takami, 2024). Mitochondrial genomes are mostly maternally inherited, with paternal inheritance observed in certain species (Havey, 1997; Havey et al., 1998; Shen et al., 2025).

Gene transfer between the chloroplast, mitochondria, and nuclear genomes is a common phenomenon in plants, playing a pivotal role in the evolution and function of organelles (Smith, 2014; Emamalipour et al., 2020). This intergenomic exchange not only induces structural changes in organelle genomes but also contributes to the increasing size and complexity of plant mitochondrial genomes over evolutionary time (Timmis et al., 2004; Knoop et al., 2010). Notably, gene transfer from both the nucleus and chloroplast to mitochondria occurs more frequently in plants compared to other eukaryotic organisms (Nugent and Palmer, 1991; Lei et al., 2012). As a result, plant mitochondrial genomes exhibit significant structural diversity, which may promote recombination and genomic rearrangements, potentially enhancing the plant’s ability to adapt to fluctuating environmental conditions (Christensen, 2013). These gene transfer events shed light on the evolutionary trajectories of plant organelle genomes. Moreover, chloroplasts and mitochondria perform complementary yet distinct roles within the cell, each adapting to specific functional demands and environmental pressures over time. Given their evolutionary and functional relationships, comparing chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes offers valuable insights into their shared evolutionary histories, gene flow dynamics, and ecological adaptations, thereby advancing our understanding of the evolution of plant organelle genomes.

Organelle genomes serve as important tools for understanding evolutionary history, genetic exchange, and species relationships (Olmstead and Palmer, 1994; Qiu et al., 2010; Tyszka et al., 2023; Yue et al., 2023). The genus Salix (ca. 330–500 dioecious shrub and tree species) is broadly distributed across the Northern Hemisphere and serves as model system due to its frequent hybridization and ecological diversity for studying organelle genome evolution (Argus, 1997; Fang et al., 1999; Skvortsov, 1999; Argus et al., 2010; Dickmann and Kuzovkina, 2014). Within this genus, species have traditionally been classified into three subgenera—Salix, Chamaetia, and Vetrix (Skvortsov, 1999), but more recent molecular phylogenomic analyses propose a revised classification with five subgenera (Chen et al., 2025), reflecting its complex evolutionary history. Although chloroplast and mitochondrial genome comparisons are increasingly applied in other plants such as Artemisia giraldii (Yue et al., 2022), Saposhnikovia divaricata (Ni et al., 2022), and Ipomoea batatas (Li G. et al., 2024), integrated organelle genome analyses in Salix remain limited.

Salix is characterized by frequent natural hybridization, weak reproductive barriers, and both wind- and insect-mediated pollination, contributing to extensive cytonuclear gene flow (Hörandl et al., 2012; Marinček et al., 2023). While the low plastome variation observed in Salix is commonly attributed to recent rapid radiation, postglacial range expansion, and persistent hybridization (Wagner et al., 2018, 2020; He et al., 2021a), molecular dating analyses focusing on shrub willow lineages reveal a more intricate evolutionary trajectory, characterized by ancient diversification, incomplete lineage sorting, and geographic fragmentation (Wagner et al., 2021a). Several studies have suggested hybridization and introgression in Salix, primarily based on nuclear genomic data (Gramlich et al., 2018; Sanderson et al., 2023). Gene flow between species resulting from hybridization can lead to phylogenetic incongruence. In particular, serial chloroplast capture—where plastid genomes are transferred across species boundaries through repeated hybridization and backcrossing—has been reported in Salix, contributing to cytonuclear discordance (Gambhir et al., 2025). The frequent hybridization, complex lineage diversification, and geographic fragmentation observed in Salix make it an ideal model for studying the evolutionary dynamics of organelle genomes, particularly in the context of interspecific gene flow. Previous studies have mostly focused on nuclear or combined nuclear and chloroplast data, while comparative analyses of chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes remain limited. Addressing this gap enables investigation into how hybridization and interspecific gene flow shape the evolutionary dynamics of organelle genomes.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the evolutionary relationships of male and female individuals from three closely related Salix species by sequencing their chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes. Three species included Salix pierotii, S. babylonica, and S. pseudolasiogyne. To extend the scope of our analysis, we incorporated additional genomic data for 8 other species from the NCBI database, expanding our dataset to include a total of 11 Salix species. Our primary objectives were to: (1) compare the organelle genomes of the species and explore their evolutionary relationships, (2) analyze potential gene transfer events between chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes, and (3) investigate whether genomic evidence of genetic admixture could be observed at the organelle level, thereby providing insights into the adaptive processes influencing the evolution of these species. Given the close relatedness, morphological similarity, and ecological overlap among S. pierotii, S. babylonica, and S. pseudolasiogyne, we hypothesized that these species may have experienced historical gene flow or genetic admixture, potentially leaving detectable signatures in their organelle genomes. As organelle genomes evolve independently of the nuclear genome, they provide complementary perspectives on evolutionary relationships. To test this hypothesis and explore the evolutionary dynamics of their organelle genomes, we sequenced the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of both male and female individuals from these species.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection, DNA extraction and sequencing

Male and female individuals of Salix pierotii (35°16’04.4”N 128°16’34.7”E), S. babylonica (35°10’17.2”N 128°58’27.5”E), and S. pseudolasiogyne (35°14’26.1”N 128°41’51.4”E) were separately collected in South Korea. Corresponding voucher specimens were deposited in the Herbarium of Changwon National University (CWNU), Korea, a publicly accessible herbarium. Voucher numbers—NG23042701, NG23042702, SN23050401, SN23050402, CC23050101, and CC23050102—along with detailed collection information are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Species identification was initially conducted by Youngmoon Kim, a PhD student at Changwon National University whose research focuses on the taxonomy of the genus Salix. The identifications were subsequently verified by Dr. Shukherdorj Baasanmunkh and Professor Hyeok Jae Choi, both plant taxonomists affiliated with the same institution. Total genomic DNA was isolated from fresh leaves following a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method (Allen et al., 2006). DNA purity and concentration were evaluated using a BioDrop uLite spectrophotometer (Biochrom Ltd., Cambridge, UK). Library preparation was carried out with the TruSeq DNA Nano kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA), and sequencing was conducted on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Supplementary Table 2). Raw reads were subjected to quality control and trimming using FastQC v.0.11.5 and Trimmomatic v.0.36 (Bolger et al., 2014), respectively, with sequencing data summary presented in Supplementary Table 3.

2.2 Organelle genome assembly and annotation

Clean Illumina paired-end reads were assembled de novo into the chloroplast genome using Velvet v.1.2.08 (Zerbino and Birney, 2008), with subsequent validation and refinement via self-mapping in Geneious Prime v.2024.0 (Kearse et al., 2012). Sequencing coverage was confirmed by calculating read depth with Sequence Alignment/Map tools (Li et al., 2009; Supplementary Figure S1; Supplementary Table 4). Species similarities were identified by performing BLAST analysis (Altschul et al., 1990). The positions of protein-coding sequences, tRNAs, and rRNAs were mapped, and their functions were annotated using PGA v.2019 (Qu et al., 2019), which facilitated the rapid annotation of the chloroplast genome. The mitochondrial genome was assembled by mapping reads to the Salix wilsonii genome as reference (NC_064688.1; Han et al., 2022) using the ‘Map to Reference’ tool in Geneious Prime v.2024.0 (Kearse et al., 2012). Completeness and coverage were additionally evaluated through self-mapping (Supplementary Figure S2; Supplementary Table 5). Gene annotation was carried out using GeSeq (Tillich et al., 2017), and the results were subsequently verified using BLASTn (Chen et al., 2015; Supplementary Table 6). All annotations were manually verified and corrected in Geneious Prime v.2024.0 (Kearse et al., 2012). The map was visualized using OGDRAW (Greiner et al., 2019).

2.3 Repetitive sequence detection in organelle genome

To detect simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in chloroplasts and mitochondrial genomes, we employed MISA (Beier et al., 2017). For chloroplast genome analysis, the parameters ‘1-10, 2-5, 3-4, 4-4, 5-3, 6-3’ were applied, while ‘1-8, 2-4, 3-4, 4-3, 5-3, 6-3’ were used for mitochondrial genomes, targeting mono- to hexanucleotide motifs. Tandem repeats were detected using Tandem Repeats Finder (Benson, 1999), with a match score of 2, mismatch and indel penalties set to 7, and a minimum alignment score threshold of 50. Additionally, the maximum period size was set to 500, the maximum repeat array size to 2,000,000 bp, and only repeats with at least 90% sequence identity were reported. For the identification of dispersed repeats, REPuter (Kurtz et al., 2001) was employed with a minimum repeat length of 30 bp and a Hamming distance threshold of 3, thereby ensuring selection of significant and sufficiently long repeats. Only repeats with at least 90% sequence identity were selected and confirmed to ensure high confidence.

2.4 Phylogenetic tree inference

Sequence data for eight Salix species, whose complete chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes are publicly accessible through the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/browse/; last accessed March 2024), were retrieved. Populus davidiana, a species closely related within the Salicaceae family, served as the outgroup; its complete chloroplast (NC_032717.1) and mitochondrial (NC_035157.1) genomes were also obtained from NCBI (Supplementary Table 7). Common protein-coding genes in the 11 Salix species were identified using Geneious Prime v.2024.0 (Kearse et al., 2012), and the sequences were then aligned using MAFFT (Katoh et al., 2002). Conserved segments of the alignments were extracted using Gblocks v.0.91b with default settings (Castresana, 2000). For phylogenetic analysis, the optimal substitution models for both chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes were determined using jModelTest v.2.1.10 (Darriba et al., 2012; Supplementary Table 8). Bootstrap support values were estimated with 1,000 replicates in MEGA 11 (Tamura et al., 2021), and a Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogeny was constructed accordingly. Bayesian Inference (BI) analysis was performed using Geneious Prime v.2024.0 (Kearse et al., 2012) over 5,000,000 generations, sampling every 5,000 generations to assess convergence and ensure robustness. The initial 25% of sampled generations were excluded as burn-in to reduce bias in the final tree.

2.5 Divergence time estimation

Divergence times among the 11 Salix species were estimated using BEAST v.2.7.6 (Bouckaert et al., 2019), based on the shared protein-coding genes. The analysis incorporated 76 chloroplast genes and 28 mitochondrial genes. A GTR substitution model with four rate categories was implemented. A relaxed molecular clock model was applied, and speciation was modeled under a Yule speciation prior. To calibrate the divergence times, two key fossil-based calibration points were utilized: (1) The divergence between Salix and Populus, with a normal prior distribution having a mean of 48 million years ago (MYA) and a standard deviation of 0.3. This estimate is based on fossil evidence, including Populus tidwellii from the early Eocene (Manchester et al., 2006), and reflects a narrow uncertainty range to account for minor variations in previous studies (Wu et al., 2015). (2) The divergence between the subgenera Salix and Vetrix, constrained within 23.76–33.99 MYA (Wu et al., 2015). Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis was conducted for 30 million generations, with convergence and sampling adequacy assessed via effective sample size (ESS) values using Tracer v.1.7.2 (Rambaut et al., 2018). The initial 10% of generations were discarded as burn-in, after which maximum clade credibility trees were constructed using TreeAnnotator v.2.7.6 (Bouckaert et al., 2019). Final trees were visualized with FigTree v.1.4 (Rambaut, 2014).

2.6 Selective pressure analysis

Selective pressure on protein-coding sequences in 11 Salix species was assessed by calculating dN/dS ratio (ω = dN/dS) for both chloroplast and mitochondrial genes, using Populus davidiana (NC_032717.1 for chloroplast; NC_035157.1 for mitochondrion) as the reference. The analysis focused on shared protein-coding genes across these species. The ω was calculated using the count-based method yn00 from the PAML package v.4.9 (Yang, 2007), applying the F3X4 codon model. In this context, values greater than one imply positive selection, values close to one denote neutral evolution, and values below one indicate purifying selection. For this purpose, nonsynonymous (dN) and synonymous (dS) substitution rates were calculated, with dN representing amino acid–altering mutations and dS representing silent mutations. To ensure accuracy, undefined (0/0) and infinite (x/0) values were excluded from the analysis.

2.7 Chloroplast and mitochondrial genome sequence similarity analysis

To identify gene transfer events, we compared chloroplast and mitochondrial genome sequences of the 11 Salix species using BLASTn (Chen et al., 2015). For this analysis, the following parameters were selected: similarity threshold of ≥ 80%, an e-value of ≤ 1e-5, and a minimum sequence length of 50 bp. Gene transfer events identified through this process were visualized using Circoletto (Darzentas, 2010), which generated circular diagrams of sequence alignments, providing a comprehensive representation of transfer events between the two genomes.

3 Results

3.1 Features of organelle genomes in three Salix species

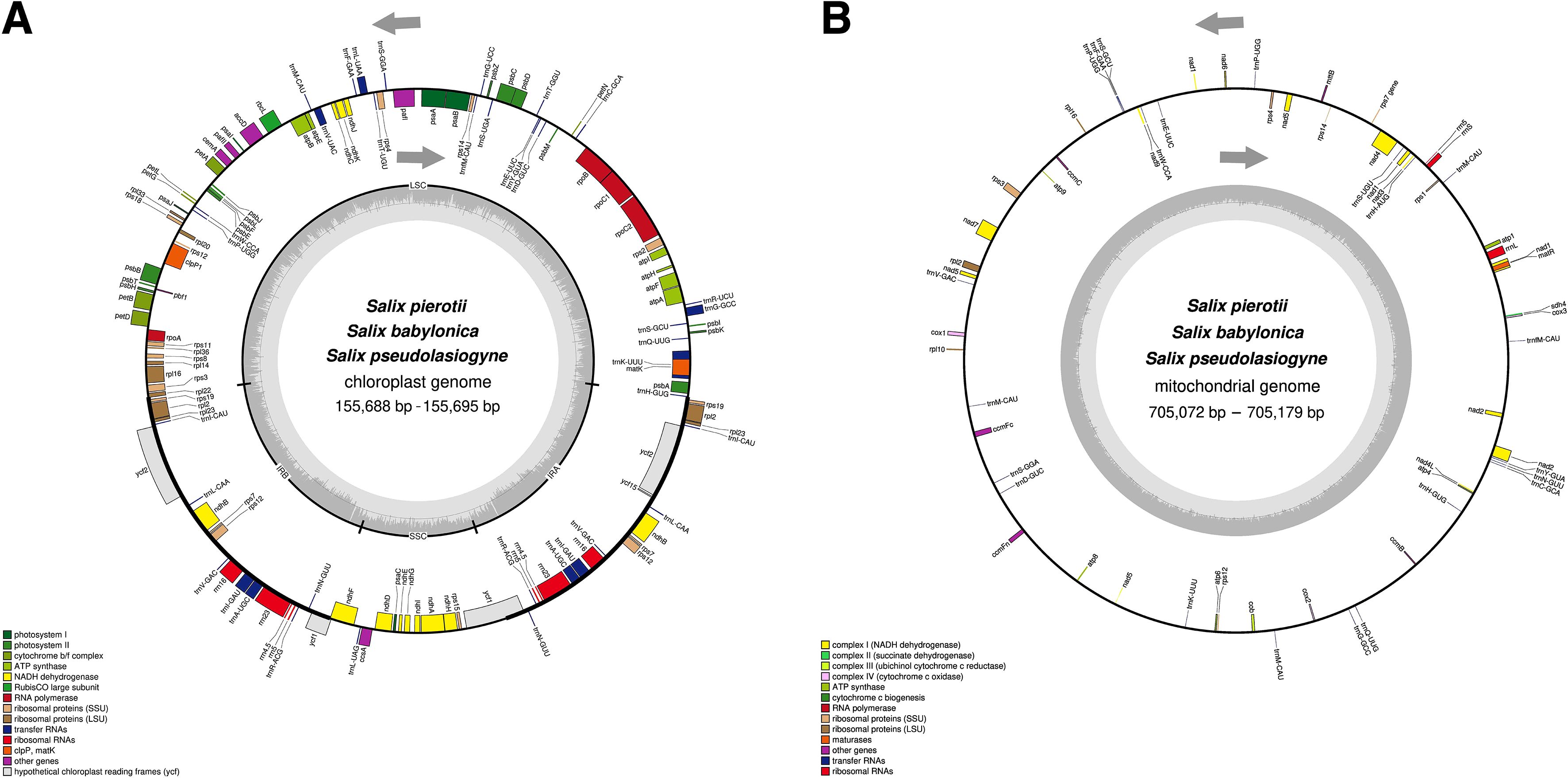

The complete chloroplast genomes of the three Salix species, namely S. pierotii, S. babylonica, and S. pseudolasiogyne, ranged from 155,688 to 155,695 bp in length, and displayed the typical quadripartite structure characteristic of chloroplast genomes. The quadripartite structure included four sections: a large single-copy (LSC), a small single-copy (SSC), and two inverted repeat (IRA and IRB) regions (Figure 1A; Supplementary Figure 3; Table 1). The GC content in the chloroplast genomes were approximately 36%, and a total of 111 genes were identified, including 77 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNAs, and 4 rRNAs. Among these, introns were present in 17 genes, with two genes (pafI and clpP1) each containing two introns (Supplementary Tables 9, 10). The mitochondrial genomes of the three Salix species were circular and ranged in size between 705,072 and 705,179 bp, with a GC content of around 44% (Figure 1B; Supplementary Figure 4; Table 2). Each mitochondrial genome of the three Salix species comprised 59 genes, including 34 protein-coding genes, 22 tRNA genes, and 3 rRNA genes. Of these, 8 contained introns, and among the tRNA genes, only two (trnM-CAU and trnP-UGG) had multiple copies (Supplementary Table 11). The mitochondrial genomes were significantly larger—approximately 4.5 times larger—than the chloroplast genomes. In addition, there is a total difference of 52 genes between the two genomes, primarily due to differences in protein-coding genes. Chloroplast genomes contain 43 more protein-coding genes, 8 tRNA genes, and 1 rRNA gene compared to mitochondrial genomes.

Figure 1. Circular maps of organelle genomes in three Salix species. (A) Circular map of the chloroplast genome. (B) Circular map of the mitochondrial genome. Genes inside the circle are transcribed in the clockwise direction, whereas genes outside the circle are transcribed counterclockwise. Genes are color-coded based on their functions, and the gray area inside the circle represents the GC content.

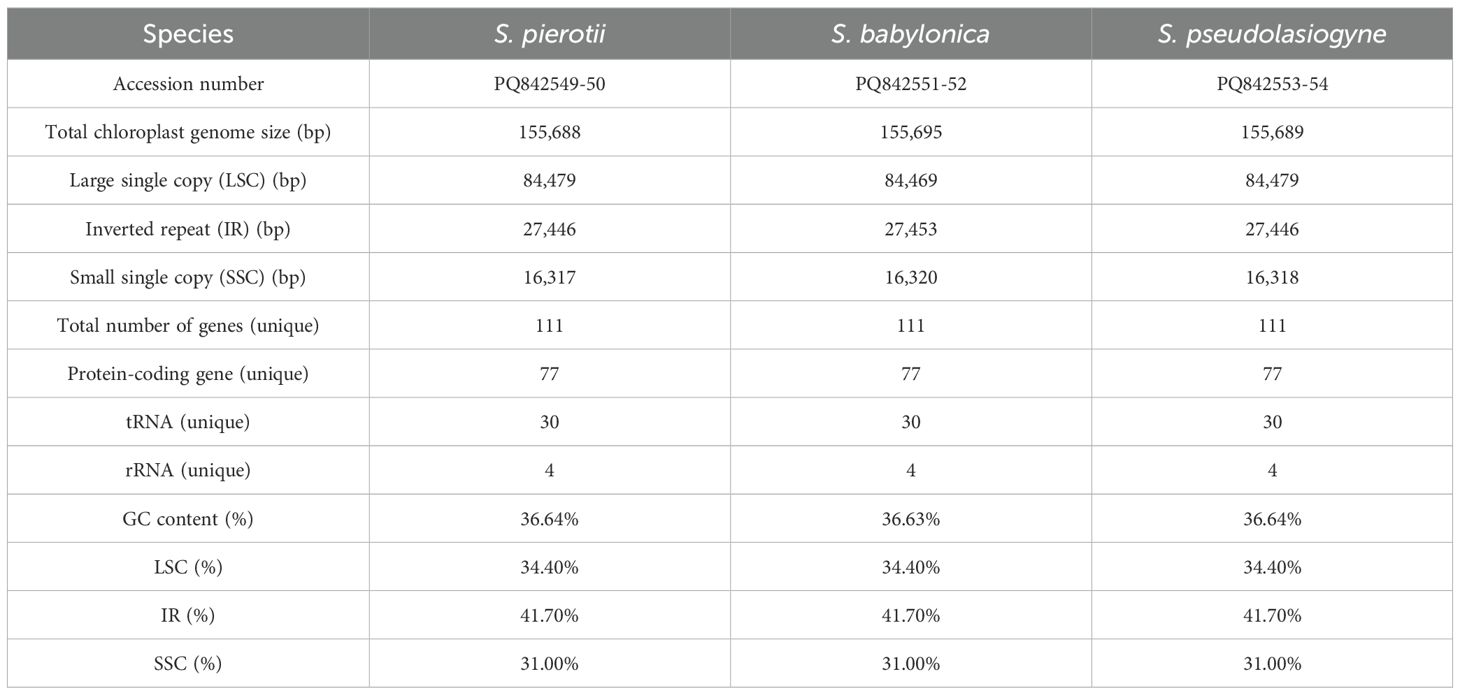

Table 1. Features of the chloroplast genomes of three Salix species (including both male and female individuals).

Table 2. Features of the mitochondrial genomes of three Salix species (including both male and female individuals).

3.2 Repetitive sequences in the organelle genomes

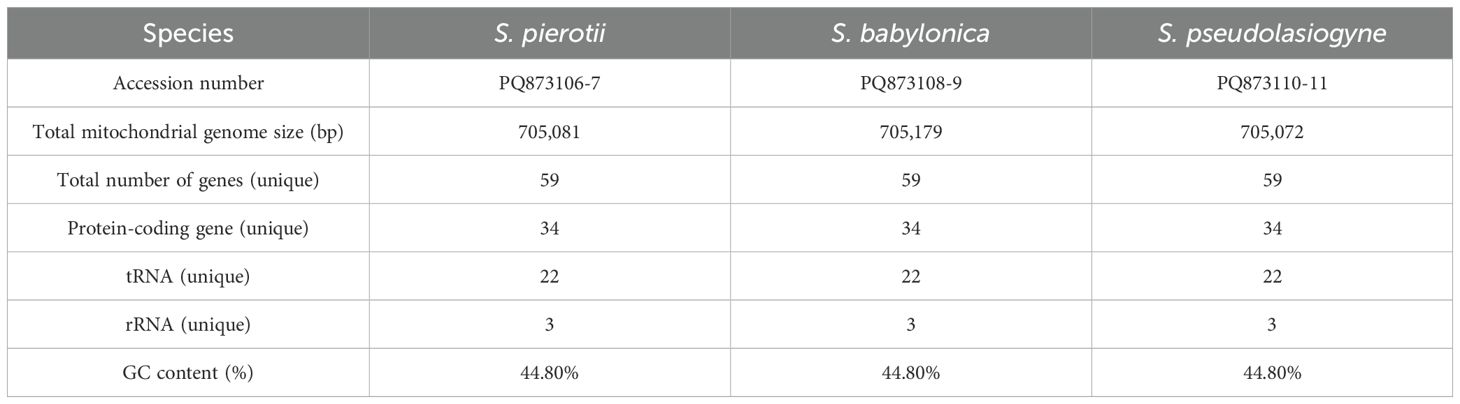

The most abundant SSRs in the chloroplast genome were mononucleotide repeats, with A/T repeats being the predominant type (Figure 2A; Supplementary Figure 5A). Among the dispersed repeats, forward repeats were the most abundant, followed by palindromic repeats, with most of these repeats being < 40 bp in length (Figure 2B; Supplementary Figure 5B). Tandem repeats primarily ranged from 30 to 51 bp in length, with the highest frequency observed in the 31–40 bp range (Supplementary Figure 5C). On the other hand, the mitochondrial genome had a greater abundance of SSRs, predominantly in the form of mononucleotide and dinucleotide repeats, with A/T and AG/CT repeats being especially prevalent (Figure 2C; Supplementary Figure 6A). The length of dispersed repeats ranged from 30 bp to over 1000 bp, with most falling within the 30–49 bp range (Figure 2D). Only forward and palindromic repeats were identified, and tandem repeats ranged from 30 to 91 bp (Supplementary Figures 6B, C). The comparison of the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes across 11 Salix species revealed that repeats in the mitochondrial genome were approximately 3 to 8 times longer in size and 4 to 5 times more abundant than those in the chloroplast genome (values have been rounded for simplicity). On average, repetitive sequences accounted for approximately 3% of the total length of the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes (Supplementary Figure 7).

Figure 2. Distribution of repeat sequences in the organelle genomes of the 11 Salix species. (A) Types of SSR motifs identified in the chloroplast genome. (B) Frequency distribution of various repeat lengths in the chloroplast genome. (C) Types of SSR motifs identified in the mitochondrial genome. (D) Frequency distribution of various repeat lengths in the mitochondrial genome.

3.3 Phylogenetic relationships and divergence estimation of the 11 Salix species

Both the chloroplast- and mitochondrial-based trees revealed two major groups, namely the Salix subgenus and Vetrix subgenus. Interestingly, S. triandra, though classified within the Salix subgenus, was more closely related to the Vetrix subgenus (Supplementary Figures 8, 9). The chloroplast-based tree showed consistent phylogenetic structure in both ML and BI analyses, whereas the mitochondrial-based tree exhibited topological inconsistencies between the two methods. Additionally, topological differences were observed between the chloroplast and mitochondrial trees. Specifically, the chloroplast-based tree identified a monophyletic group within the Salix subgenus, which comprised S. pierotii, S. babylonica, and S. pseudolasiogyne. Salix wilsonii and S. dunnii were also grouped together, and the five species from the Vetrix and Chamaetia subgenera formed a monophyletic clade. Additionally, S. suchowensis was closely related with S. koriyanagi, whereas S. purpurea showed close relationship with S. integra. In contrast, the mitochondrial-based trees showed some discrepancies. The ML and BI trees did not group S. wilsonii and S. dunnii together. Although the five species from the Vetrix and Chamaetia subgenera formed a monophyletic clade, the ML tree did not group S. purpurea and S. integra together. Instead, S. suchowensis and S. koriyanagi showed a closer phylogenetic relationship. However, in the BI tree, S. suchowensis and S. purpurea were grouped together.

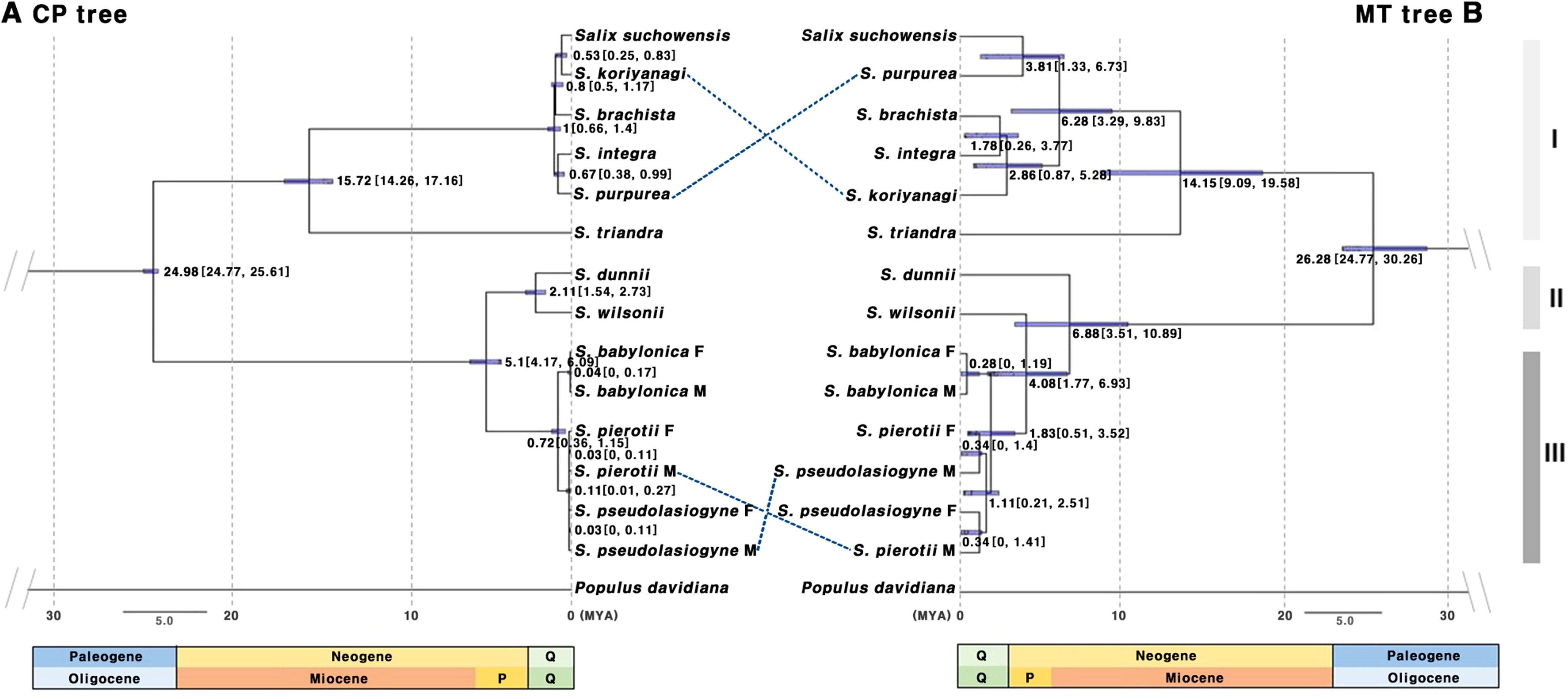

Divergence time estimation indicated that the first divergence among the 11 Salix species occurred during the Oligocene, approximately 24–26 MYA (Figure 3). Consistent topologies were observed for ML and BI trees, indicating a similar divergence time among the Salix species. Based on the tree-based analysis, species were grouped into three categories: Group I (G1), including species from the sections Amygdalinae, Caesiae, Haoanae, Helix, and Lindleyanae; Group II (G2), containing species from the section Wilsonia; and Group III (G3), consisting of species from the section Salix. The chloroplast-based tree revealed that Group G1 diverged approximately 15.72 MYA (Miocene, 95% highest posterior density or HPD: 14.26–17.16 MYA), with most divergences within G1, G2, and G3 occurring during the Quaternary period. In contrast, the mitochondrial-based tree revealed that G1 and G2 began diverging in the Miocene, with subsequent divergences occurring during the Pliocene and Quaternary. Both the chloroplast- and mitochondrial-based trees indicated that G1, G2, and G3 formed monophyletic clades, although some topological discrepancies were observed between the trees for certain species. Specifically, in G1, discrepancies between S. koriyanagi and S. purpurea were observed. Similarly, in G3, discrepancies were found between the male (M) individuals of S. pierotii (M) and those of S. pseudolasiogyne (M). These discrepancies may reflect differences in phylogenetic topology between the two organelle genomes, potentially attributable to recent divergence, hybridization, or distinct evolutionary dynamics. Moreover, the mitochondrial-based tree further supported that, within G3, S. pierotii and S. pseudolasiogyne were genetically closer to each other than to S. babylonica.

Figure 3. Chronogram based on protein-coding gene sequences from 11 Salix species. (A) Tree constructed using chloroplast genes. (B) Tree constructed using mitochondrial genes. The molecular clock trees were generated using the BEAST program. Numbers on the branches represent the mean divergence times, and the blue bars indicate the 95% highest posterior density (HPD) intervals. Age estimates are presented in millions of years ago (MYA). Q, Quaternary includes the Holocene and Pleistocene; P, Pliocene; Group I (G1): other sections, Group II (G2): sect. Wilsonia, Group III (G3): sect. Salix; M, Male; F, Female.

3.4 Selection pressure analysis

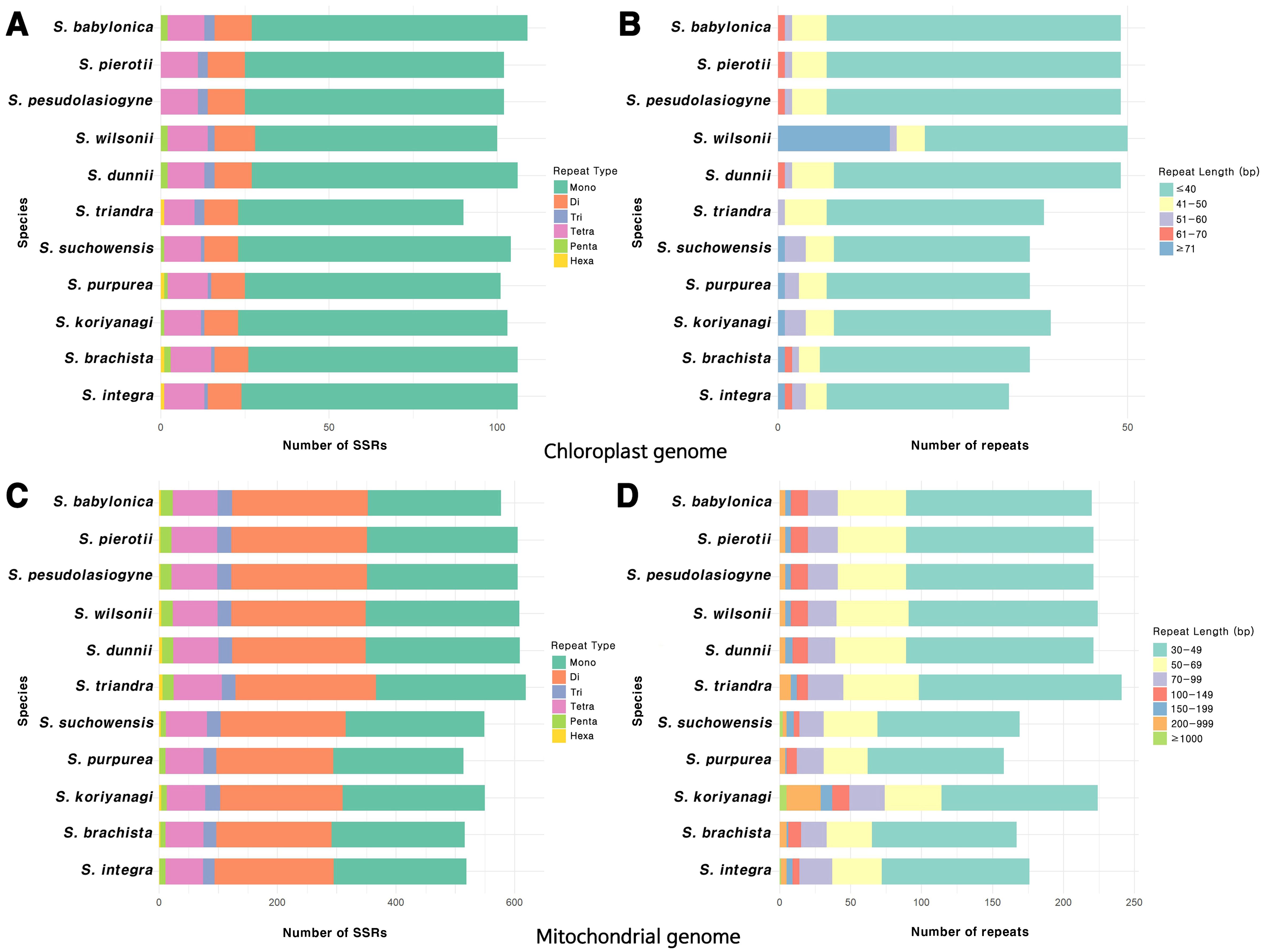

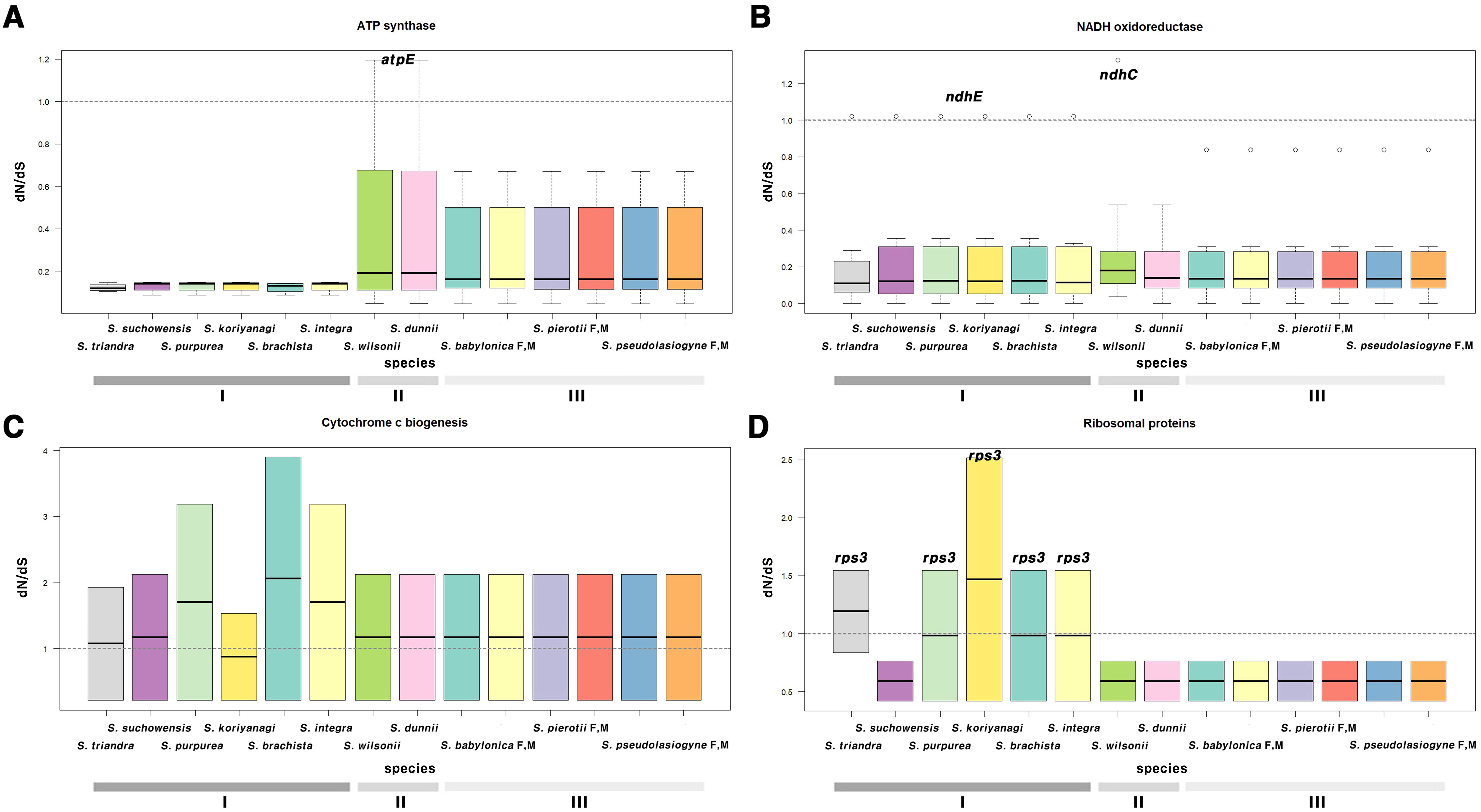

G1, G2, and G3, categorized by section, clustered similarly in terms of selection pressure (Figure 4; Supplementary Figures 10, 11; Supplementary Tables 12, 13). Most genes had ω < 1, indicating purifying selection; only a few genes exhibited ω > 1. In the chloroplast genome, genes such as atpE, ndhC, and ndhE showed elevated ω values, with ndhE in G1 (ω = 1.0223) and atpE in G2 (ω = 1.1952) showing signs of positive selection (Figures 4A, B). In the mitochondrial genome, genes that exhibited signals of positive selection included ccmFc, cox3, rps3, matR, and nad4 (Supplementary Table 13). Notably, two genes, namely matR and ccmFc, exhibited positive selection across all 11 species (Figure 4C). In S. triandra of G1, nad4 had an ω of 1.1731, whereas cox3 and rps3 showed ω > 1 in most G1 species (Figure 4D). Among mitochondrial genes, ccmFc showed relatively high ω values ranging from 1.9293 to 3.9009, and rps3 ranged from 1.5445 to 2.5163, and cox3 showed a value of 3.9641.

Figure 4. Boxplot of dN/dS ratios for chloroplast and mitochondrial genes, categorized by functional groups. Genes related to (A) ATP synthase, (B) NADH oxidoreductase, (C) cytochrome c biogenesis, and (D) ribosomal proteins. (A, B) represent chloroplast genes, while (C, D) represent mitochondrial genes. The horizontal line inside the box represents the median. The box extends from the first quartile (Q1) to the third quartile (Q3), and outliers are shown as individual points not connected by vertical lines above or below the box. Group I (G1): other sections, Group II (G2): sect. Wilsonia, Group III (G3): sect. Salix; M, Male; F, Female.

3.5 Gene transfer from chloroplast to mitochondria

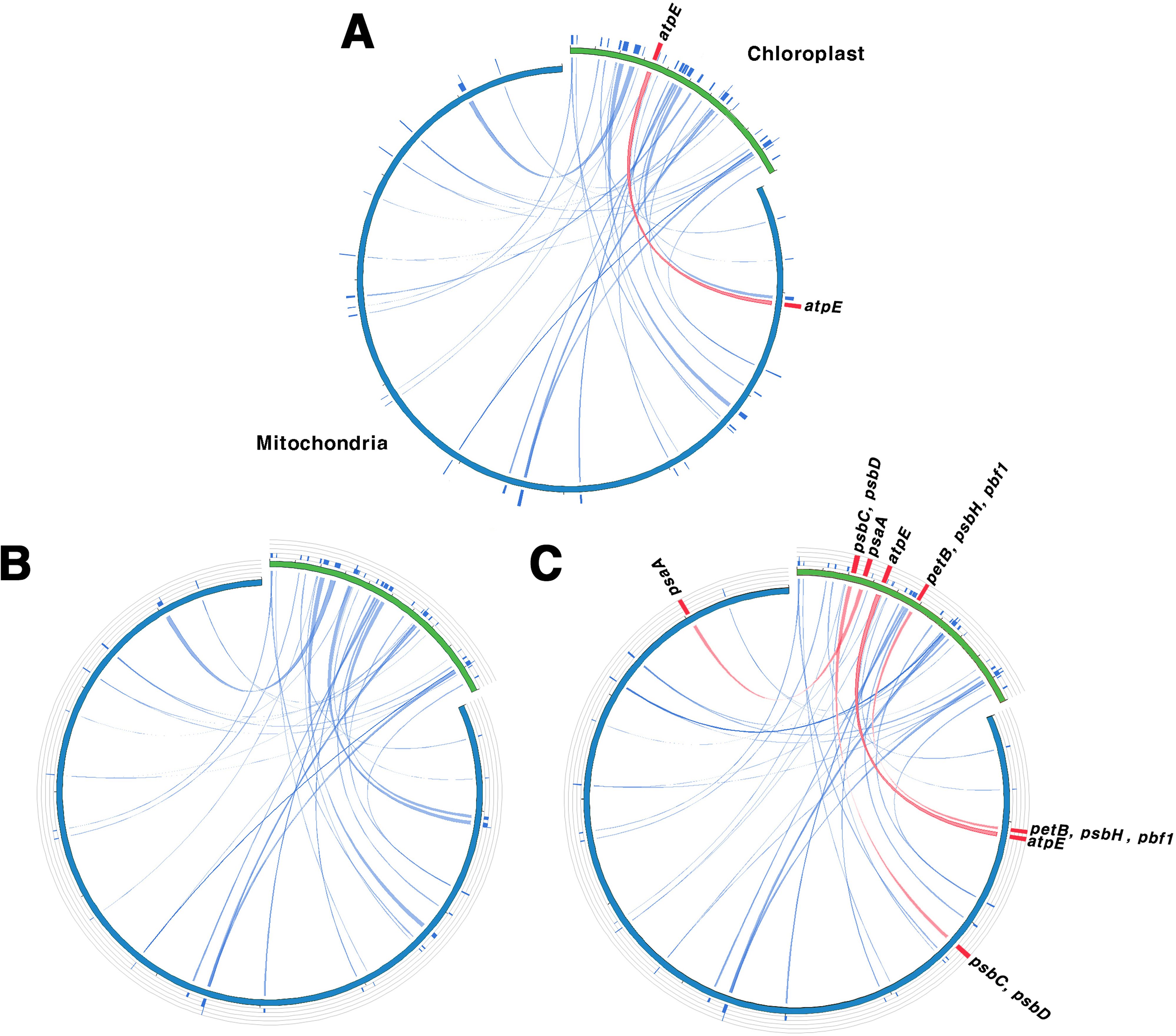

The sequence similarity between the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes was consistent among the two tree-based analyses, grouping the species into G1, G2, and G3 (Figure 5). This grouping was indicative of complete gene transfer events. Chloroplast homologous fragments, ranging from 31 to 43 bp, were also present in the mitochondrial genome, indicating that numerous sequence fragments have undergone gene transfer (Supplementary Tables 14, 15). We classified gene transfer into two categories: partial transfers, where only a portion of the gene sequence was transferred, and complete transfers, where the entire gene sequence was transferred. For protein-coding genes, there were about 12–14 partial transfers and between 0–7 complete transfers. In G1, only atpE underwent complete gene transfer, whereas G2 exhibited only partial transfers and no complete gene transfers. In contrast, G3 exhibited the highest number of complete gene transfers, with seven genes—psaA, psbC, D, H, pbf1, petB, and atpE—being fully transferred. Additionally, after removing duplicate sequences, we identified 10 to 11 cases of tRNA gene transfer across the three groups.

Figure 5. Homologous sequences shared between the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes. (A–C) serve as representatives for Groups I, II, and III, respectively. Green indicates the chloroplast genome, while blue indicates the mitochondrial genome. Blue lines represent homologous fragments, and the red lines show complete transferred genes. Group I (G1): other sections, Group II (G2): sect. Wilsonia, Group III (G3): sect. Salix.

4 Discussion

4.1 Characteristics of organelle genomes in three Salix species

The chloroplast genome size observed for the three Salix species were consistent with previously reported ranges for the genus Salix (Wang and Yang, 2016; Wu and Li, 2022; Yang et al., 2022). The genes identified in the chloroplast genomes in the present study closely resembled those reported previously in S. babylonica (Wang and Yang, 2016), with the exception of one gene. Specifically, the ycf15 was absent due to pseudogenization, a phenomenon commonly observed in many plant species due to early stop codons (Steane, 2005; Li et al., 2017). The conserved structure and composition of the chloroplast genome highlights its critical role in photosynthesis, plant growth, and stress responses (Wicke et al., 2011; Song et al., 2021).

The mitochondrial genomes of the three analyzed Salix species shared a consistent circular structure, which aligns with previously reported mitochondrial genomes in Salix species (Han et al., 2022; Ye et al., 2017). These genomes comprised 59 genes, which was within the range (55–59 genes) reported previously for other Salix species (Han et al., 2022; Ye et al., 2017). This relatively small gene set is a characteristic feature of plant mitochondrial genomes, which have undergone significant gene loss or gene transfer to the nuclear genome over the course of evolution (Adams et al., 2002). Despite the reduced gene content, the remaining genes are crucial for vital cellular functions, including energy metabolism. The genome sizes of the 11 Salix mitochondrial genomes were different, ranging from 598,970 bp in S. purpurea to 735,196 bp in S. triandra. These differences in genome length were likely due to structural variability, a common feature of plant mitochondrial genomes. This variability indicates their ability to undergo structural rearrangements, including duplications and deletions, and highlight the ability of plant mitochondria to adapt to diverse environmental conditions, thereby reinforcing the critical role played by plant mitochondrial genomes (Mackenzie and McIntosh, 1999; Morley and Nielsen, 2017).

4.2 Repeat element contributions to genome length

We identified 90–109 SSRs in the chloroplast genomes and 514–619 SSRs in the mitochondrial genomes (Figure 2). The prevalence of A/T repeat sequences indicates a higher occurrence of poly(A) and poly(T) sequences, which is a common pattern observed in many plant species (Kuntal and Sharma, 2011; Martin et al., 2013; Curci et al., 2015). The number of SSRs identified in the chloroplast genomes of Salix species in this study falls within the range previously reported in a comparative analysis of 10 Salix species, which identified 80–111 SSRs with repeat lengths of 30–35 bp (Yuan et al., 2025). Similarly, our mitochondrial SSR results are consistent with earlier findings, where species such as S. wilsonii, S. cardiophylla, S. paraflabellaris, and S. suchowensis were reported to contain around 608 SSRs and large dispersed repeats exceeding 1,000 bp (Ye et al., 2017). These results support the observation that mitochondrial genomes harbor longer repeat sequences than chloroplast genomes. However, when comparing the proportion of repetitive sequences relative to the chloroplast or mitochondrial genome length, both organelles exhibited similar average values of approximately 3%. This suggests that the greater abundance of repeats in the mitochondrial genome is primarily attributable to its larger genome size. Frequent DNA exchanges with the nuclear and chloroplast genomes, the presence of large introns, and extensive non-coding regions are also likely to have contributed to the overall expansion of the mitochondrial genome (Timmis et al., 2004; Dong et al., 2018). Repeat sequences also play a crucial role in shaping the structure of organelle genome. The abundance of repeat sequences is closely associated with recombination, which plays a critical role in the evolutionary dynamics of organelle genomes. Furthermore, repeat units and their associated sequences often induce structural changes within organelle genomes (Sinn et al., 2018; Varré et al., 2019; Zou et al., 2022).

4.3 Understanding phylogeny and evolutionary dynamics in Salix using organelle genomes

Based on the phylogenetic tree-based analyses, the 11 Salix species were grouped into two main subgenera, Salix and Vetrix, which is consistent with previous studies (Wu et al., 2015; Ren et al., 2022). While Salix is generally classified into three major subgenera—Salix, Chamaetia, and Vetrix (Skvortsov, 1999)—we found that Chamaetia appeared to be included within Vetrix. This supports the findings of recent studies, which suggest that Chamaetia and Vetrix form a single clade (Wu et al., 2015; Wagner et al., 2018, 2020, 2021). Furthermore, a recent molecular phylogenomic study proposed an updated classification that recognizes five subgenera within Salix, namely Salix, Urbaniana, Triandrae, Longifoliae, and Vetrix (Chen et al., 2025). The chloroplast-based trees showed consistent topologies across both ML and BI methods, whereas the mitochondrial-based trees exhibited some topological discrepancies (Supplementary Figures 8, 9). Such discrepancies between the ML and BI trees may arise from differences in the statistical models employed by each method. Several studies have discussed potential causes for these topological inconsistencies, including differences in genomic regions analyzed, methodological approaches, and model assumptions (Huelsenbeck, 1995; Sullivan and Joyce, 2005; Som, 2014). Among the species analyzed, S. triandra occupies a unique position at the boundary between the Salix and Vetrix subgenera, and its phylogenetic placement has long been debated (Ren et al., 2022; Wu and Li, 2022; Trybush et al., 2008). This debate arises from the similar heterostyly system shared with other Vetrix species, as well as the genetic overlap between the Salix and Vetrix subgenera, further complicated by potential hybridization events (Li et al., 2020; Gulyaev et al., 2022). Recent phylogenomic studies have suggested recognizing Triandrae as a distinct subgenus (Chen et al., 2025). In our study, the three male and female individuals analyzed formed a monophyletic group, with S. pierotii and S. pseudolasiogyne clustering closely together. The organelle genome sequences of these two species exhibited minimal variation, with the chloroplast genome showing insufficient divergence to resolve species-level relationships. This limited divergence is not unique to these species but rather reflects the overall high conservation of chloroplast genomes in the Salix species, which can likely be attributed to strict functional constraints, low mutation rates, and limited recombination. This pattern is consistent with reports that chloroplast genome variation in Salix is much lower compared to other angiosperms (Wagner et al., 2021b), further emphasizing the extremely conserved nature of the chloroplast genome within the genus. This strong conservation reduces phylogenetic resolution, posing challenges for species delimitation and evolutionary inference. Given these limitations, incorporating nuclear or mitochondrial genome data may provide additional resolution and improve species-level phylogenetic studies within this genus.

In light of the close phylogenetic relationships among the three Salix species—S. pierotii, S. babylonica, and S. pseudolasiogyne—we hypothesized that these species may have experienced historical gene flow or genetic admixture due to their genetic relatedness. Hence, we estimated the divergence times of 11 Salix species and analyzed their evolutionary relationships, focusing on the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes (Figure 3). The first divergence among the 11 Salix species was estimated at 24.98 MYA (95% HPD: 24.77–25.61) for the chloroplast genome and 26.28 MYA (95% HPD: 24.77–30.26) for the mitochondrial genome, suggesting that the two organelles diverged within a very similar time frame. Beyond the initial divergence, the internal branching patterns of the chloroplast and mitochondrial phylogenies differed. The mitochondrial tree displayed longer internal branches among species, indicating greater sequence divergence and lineage differentiation. In contrast, the chloroplast tree exhibited shorter branches and tighter species clustering, suggesting either more recent divergence or stronger sequence conservation (Figure 3). We also observed discrepancies between G1 and G3, likely owing to differences in evolutionary pressures and evolutionary rates affecting each genome. Chloroplast genomes are typically more conserved and exhibit lower genetic diversity compared to mitochondrial and nuclear genomes. This is primarily due to their maternal inheritance and their essential role in photosynthesis, which contribute to maintaining a stable genomic structure over time (Zurawski and Clegg, 1987; Wicke et al., 2011). The slower evolution observed in Salix can be explained by its characteristics as a woody plant, including longer life cycles and slower growth rates. In contrast, plant mitochondrial genomes, although characterized by low mutation rates, exhibit greater structural variability compared to chloroplast genomes. This encompasses gene rearrangements, structural variations, and frequent recombination events. Such structural flexibility allows plant mitochondrial genomes to adapt to various environmental pressures, playing a key role in shaping the evolutionary patterns of plant species. As a result, mitochondrial genomes contribute to broader processes of plant genome evolution and diversification (Palmer and Herbon, 1988; Gualberto and Newton, 2017; Sun et al., 2022), leading to evolutionary patterns distinct from those of the more stable chloroplast genomes.

Within the mitochondrial-based phylogeny of G3, our data indicate potential gene flow or genetic admixture between S. pierotii and S. pseudolasiogyne, estimated at 4.08–6.88 MYA, before the divergence of S. wilsonii. The observed clustering of these species in the mitochondrial tree could reflect recent divergence, historical or partial gene exchange, or unresolved polytomies resulting from rapid, nearly simultaneous divergences. Mitochondrial genomes, due to their dynamic structural evolution and tendency for gene exchange, are particularly responsive to external genetic influx, which can obscure species boundaries and complicate interpretations of evolutionary history (Zakharov et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2023). In contrast, chloroplast genomes are highly conserved due to their essential role in photosynthesis, whereas mitochondrial genomes exhibit structural flexibility and frequent recombination (Gualberto et al., 2014). Despite their generally maternal inheritance, organelle genomes provide valuable, albeit sometimes partial, insights into evolutionary relationships. The observed patterns of gene flow or genetic admixture could be indicative of putative historical hybridization events, although organelle data alone cannot conclusively confirm hybridization. Nuclear genomic analyses, which capture biparental inheritance, are therefore crucial for validating these patterns and assessing the contribution of hybridization to species genomic composition (Greiner et al., 2015). Studies using nuclear markers suggest that hybridization is common in Salix and may help explain patterns of evolutionary change, potentially contributing to species diversification (Wagner et al., 2020; Barcaccia et al., 2014; Vašut et al., 2024). In our analysis of male and female individuals from the three studied species, sex-specific patterns were not evident; nonetheless, considering dioecy could provide additional context when interpreting gene flow and evolutionary dynamics in Salix (Nybakken and Julkunen-Tiitto, 2013).

4.4 Selective pressures on chloroplast and mitochondrial genes

The dN/dS analysis results showed that most genes in Group I (G1, section Amygdalinae, Caesiae, Haoanae, Helix, and Lindleyanae), Group II (G2, section Wilsonia), and Group III (G3, sections Salix) underwent neutral evolution or purifying selection, though several genes showed evidence of positive selection (Figure 4; Supplementary Figures 10, 11; Supplementary Tables 12, 13). A distinct separation was evident between the groups (Figure 4A), potentially shaped by environmental factors or habitat-specific characteristics. G1, which primarily comprised shrubs, may exhibit differences in photosynthetic efficiency, growth rate, or adaptation strategies compared to species in G2 and G3 (Santos et al., 2025). G2 comprised species from the subtropical regions of China, which appear to share similar environmental stresses or climatic conditions (Fang et al., 1999; Zurawski and Clegg, 1987; He et al., 2021b). Due to their geographic proximity and similar environmental conditions, G3 species appear to experience comparable selective pressures. As ATP synthase plays a critical role in plant photosynthesis (Westhoff et al., 1985), these ecological contexts may have contributed to the divergence in photosynthetic gene evolution. While growth form may influence certain aspects of adaptation, the consistent patterns observed across diverse Salix habitats highlight the predominant role of environmental conditions in shaping genomic evolution.

Chloroplast and mitochondrial genes showing evidence of positive selection were further examined to assess their functional significance and potential adaptive roles. Due to the demand for rapid activation, the atpE gene rate (Rott et al., 2011; Chotewutmontri and Barkan, 2016) exhibited a high evolutionary. The ndh gene family (from ndhA to ndhK) (Martin et al., 1996; Endo et al., 1999; Yamori et al., 2011; Li Q. et al., 2024), involved in the chloroplast electron transport chain, is crucial for adaptation to environmental stresses such as high light intensity and low temperatures. In G2, atpE appears to have undergone positive selection likely after its divergency from G3, ~5.1 MYA (95% HPD: 4.17–6.09). Similarly, the ndhC in S. wilsonii underwent positive selection ~2.11 MYA (95% HPD: 1.54–2.73) after diverging from S. dunnii. Positive selection for ndhE in G1 was estimated to have occurred between 15.72 and 24.98 MYA. Most mitochondrial genes had ω values <1, though some genes exhibited different patterns. The matR gene (Adams et al., 2002), essential for mitochondrial function, showed evidence of positive selection across all species in G1, G2, and G3. Additionally, ccmFc (Giegé et al., 2004), which is essential for cytochrome c maturation, consistently exhibited ω >1 (mean = 2.5) across all species. No additional positively selected mitochondrial genes were identified in G2 or G3. In G1, nad4 gene in S. triandra is a subunit of NADH dehydrogenase and is thought to have adapted to environmental conditions post divergence ~14.15 MYA (95% HPD: 9.09–19.58). Additionally, the rps3 (Passmore et al., 2007) in mitochondrial ribosomes, essential for protein translation initiation, exhibited a dN/dS ratio >1.5 in all G1 species except S. suchowensis, indicating positive selection. Interestingly, S. suchowensis shared some gene patterns with species in G2 and G3, suggesting exposure to similar environmental pressures. These results indicate that both chloroplast and mitochondrial genes have undergone group-specific adaptation to environmental pressures, highlighting the diverse evolutionary dynamics of the Salix species.

Some mitochondrial genes, particularly ccmFc, cox3 and rps3, exhibited relatively higher dN/dS ratios than chloroplast genes, suggesting stronger positive selection. Hence, mitochondrial genomes may experience stronger selective pressures than chloroplast genomes, likely due to their distinct functions and unique genetic and metabolic characteristics (Jiang et al., 2018). Mitochondrial genes often show high variability in non-synonymous substitution rates among genes and lineages (Lynch et al., 2006; Richardson et al., 2013; Smith and Keeling, 2015). In contrast, chloroplast genomes accumulate relatively few non-synonymous substitutions, reflecting strong purifying selection to maintain essential photosynthetic functions. This difference may explain the stronger signals of positive selection observed in mitochondrial genes in this study. The contrasting selective pressures between the two organelles suggest that mitochondrial genes are subject to more dynamic evolutionary forces, likely driven by environmental adaptation and metabolic demands. Moreover, the evidence of positive selection in both organelles indicates the crucial role of cytoplasmic genome evolution in shaping the ecological adaptability of Salix, potentially contributing to its success across diverse environmental conditions.

4.5 Evolutionary patterns of chloroplast gene migration to mitochondria

Gene transfer between organelle and nuclear genomes as well as between different organelle genomes is a frequent and well-documented phenomenon in plants (Nguyen et al., 2000; Bergthorsson et al., 2003; Timmis et al., 2004). These transfers are crucial in genome evolution, contributing to genetic diversity and complexity (Huang et al., 2005; Yue et al., 2022). To investigate gene transfer relationships between chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes in Salix, we analyzed homologous fragments (Figure 5; Supplementary Tables 14, 15). Our analysis grouped the 11 Salix species into three distinct groups. G1 corresponded to subgenus Salix s.str., G2 to subgenus Protitea, and G3 to species primarily classified under subgenus Chamaetia/Vetrix (Wu et al., 2015). Despite its ambiguous taxonomic status, S. triandra, was assigned to G3 due to its clustering with Chamaetia/Vetrix species in earlier phylogenetic analyses (Yuan et al., 2025). All three groups exhibited homologous sequences and evidence of chloroplast-derived sequences in the mitochondrial genome, indicating potential gene transfer events. These events likely predated the divergence of G1, G2, and G3, which is estimated to have occurred around 24.95–26.28 MYA. Among the transferred sequences, tRNA genes were the most frequently transferred. Many of these transferred sequences, including tRNA genes, appear to have undergone pseudogenization (Straub et al., 2013; Wee et al., 2022). Although the transfer events likely occurred before the divergence of these groups, the number of retained transferred genes varied among them: G3 contained seven transferred genes, whereas G1 and G2 had only 0–1. This suggests that G3 may have preserved or accumulated more transferred sequences, possibly due to distinct evolutionary pressures, greater genomic plasticity, or adaptation to specific environmental conditions.

These three groups indicated how environmental factors, gene transfer, and evolutionary processes have shaped genetic diversity in Salix. It also facilitates better understanding of how gene flow interacts with ecological pressures. Our findings indicate that Salix species have adapted to common environmental conditions—such as climate, habitat, and interspecific competition—resulting in divergent yet interconnected lineages. Closely related species, including S. pierotii, S. babylonica, and S. pseudolasiogyne, share overlapping habitats and similar reproductive strategies, which likely facilitated gene flow or genetic admixture. Additionally, recent divergence, continued hybridization, and introgression likely blur species boundaries and promote genetic fluidity. Notably, gene flow was observed exclusively in the mitochondrial genome, suggesting distinct evolutionary constraints compared to the chloroplast genome.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we revealed contrasting evolutionary dynamics between chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes across 11 Salix species, thereby providing key insights into organelle genome evolution and intergenomic interactions. Our analysis identified distinct evolutionary patterns, with the mitochondrial genome showing relatively clearer phylogenetic separation among species than the chloroplast genome. This difference can be attributed to their functional roles: the chloroplast genome remained highly conserved due to its central role in photosynthesis, whereas the mitochondrial genome showed greater structural and evolutionary flexibility in response to environmental pressures. Moreover, several mitochondrial genes were found to be under stronger positive selection than their chloroplast counterparts, further illustrating their divergent evolutionary trajectories. We also detected evidence of gene transfer between chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes, highlighting functional interconnections between these organelles. These intergenomic exchanges may contribute to structural variations in the mitochondrial genome and influence the evolutionary dynamics of the Salix species. Notably, mitochondrial genome data suggested signals of potential gene flow or genetic admixture. These findings underscore the complementary role of mitochondrial genome analysis in resolving phylogenetic relationships and highlighting possible historical inter-species genetic exchange, especially given the limitations of the highly conserved chloroplast genome. Our integrative framework highlights the value of incorporating mitochondrial data into organelle genome studies and may serve as a foundation for broader applications in plant evolutionary biology and comparative genomics.

Data availability statement

The raw read data generated in this study are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1205789. Additionally, the newly sequenced chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes can be accessed in the NCBI database under the accession numbers PQ842549-54 and PQ873106-11.

Author contributions

YsK: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Software. SJ: Data curation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. SB: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Validation. YmK: Writing – original draft, Investigation. HC: Writing – review & editing. IP: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by Korea Basic Science Institute (National research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Ministry of Education. (Grant No. 2023R1A6C101B022). Additional support was provided by Global - Learning & Academic research institution for Master’s·PhD students, and Postdocs (LAMP) Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (No. RS2024-00444460).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1693183/full#supplementary-material

References

Adams, K. L., Qiu, Y. L., Stoutemyer, M., and Palmer, J. D. (2002). Punctuated evolution of mitochondrial gene content: high and variable rates of mitochondrial gene loss and transfer to the nucleus during angiosperm evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 9905–9912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042694899

Allen, G. C., Flores-Vergara, M., Krasynanski, S., Kumar, S., and Thompson, W. (2006). A modified protocol for rapid DNA isolation from plant tissues using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2320–2325. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.384

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., and Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

Argus, G. W. (1997). Infrageneric classification of Salix (Salicaceae) in the new world. Syst. Bot. Monogr. 52, 1–121. doi: 10.2307/25096638

Argus, G. W., Eckenwalder, J. E., Kiger, R. W., and Flora of North America Editorial Committee (2010). “Salicaceae,” in Flora of North America (Oxford University Press, Oxford), 3–164.

Barcaccia, G., Meneghetti, S., Lucchin, M., and De Jong, H. (2014). Genetic segregation and genomic hybridization patterns support an allotetraploid structure and disomic inheritance for Salix species. Diversity 6, 633–651. doi: 10.3390/d6040633

Beier, S., Thiel, T., Münch, T., Scholz, U., and Mascher, M. (2017). MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 33, 2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198

Benson, G. (1999). Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573

Bergthorsson, U., Adams, K. L., Thomason, B., and Palmer, J. D. (2003). Widespread horizontal transfer of mitochondrial genes in flowering plants. Nature 424, 197–201. doi: 10.1038/nature01743

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M., and Usadel, B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170

Bouckaert, R., Vaughan, T. G., Barido-Sottani, J., Duchêne, S., Fourment, M., Gavryushkina, A., et al. (2019). BEAST 2.5: An advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 15, e1006650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006650

Castresana, J. (2000). Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334

Chang, S., Yang, T., Du, T., Huang, Y., Chen, J., Yan, J., et al. (2011). Mitochondrial genome sequencing helps show the evolutionary mechanism of mitochondrial genome formation in Brassica. BMC Genomics 12, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-497

Chen, K. Y., Wang, J. D., Xiang, R. Q., Yang, X. D., Yun, Q. Z., Huang, Y., et al. (2025). Backbone phylogeny of Salix based on genome skimming data. Plant Diversity 47, 178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.pld.2024.09.004

Chen, Y., Ye, W., Zhang, Y., and Xu, Y. (2015). High speed BLASTN: an accelerated MegaBLAST search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 7762–7768. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv784

Chotewutmontri, P. and Barkan, A. (2016). Dynamics of chloroplast translation during chloroplast differentiation in maize. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006106

Christensen, A. C. (2013). Plant mitochondrial genome evolution can be explained by DNA repair mechanisms. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 1079–1086. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt069

Curci, P. L., De Paola, D., Danzi, D., Vendramin, G. G., and Sonnante, G. (2015). Complete chloroplast genome of the multifunctional crop globe artichoke and comparison with other Asteraceae. PLoS One 10, e0120589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120589

Daniell, H., Lin, C. S., Yu, M., and Chang, W. J. (2016). Chloroplast genomes: diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 17, 134. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1004-2

Darriba, D., Taboada, G., Doallo, R., and Posada, D. (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 9, 772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109

Darzentas, N. (2010). Circoletto: visualizing sequence similarity with Circos. Bioinformatics 26, 2620–2621. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq484

Dickmann, D. I. and Kuzovkina, J. (2014). “Poplars and willows of the world, with emphasis on silviculturally important species,” in Poplars and willows: Trees for society and the environment. Eds. Isebrandsand, J. G. and Richardson, J. (CABI Publishing, Wallingford, UK), 8–91.

Dong, S., Zhao, C., Chen, F., Liu, Y., Zhang, S., Wu, H., et al. (2018). The complete mitochondrial genome of the early flowering plant Nymphaea colorata is highly repetitive with low recombination. BMC Genomics 19, 614. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4991-4

Emamalipour, M., Seidi, K., Zununi, V. S., Jahanban-Esfahlan, A., Jaymand, M., Majdi, H., et al. (2020). Horizontal gene transfer: from evolutionary flexibility to disease progression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 229. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00229

Endo, T., Shikanai, T., Takabayashi, A., Asada, K., and Sato, F. (1999). The role of chloroplastic NAD(P)H dehydrogenase in photoprotection. FEBS Lett. 457, 5–8. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00989-8

Fang, C. F., Zhao, S. D., and Skvortsov, A. K. (1999). “Salicaceae,” in Flora of China. Eds. Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H., and Hong, D. Y. (Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO), 139–274.

Gambhir, D., Sanderson, B. J., Guo, M., Hu, N., Khanal, A., Cronk, Q., et al. (2025). Disentangling serial chloroplast captures in willows. Am. J. Bot. 112, e70039. doi: 10.1002/ajb2.70039

Giegé, P., Rayapuram, N., Meyer, E. H., Grienenberger, J. M., and Bonnard, G. (2004). CcmFC involved in cytochrome c maturation is present in a large sized complex in wheat mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 563, 165–169.

Gramlich, S., Wagner, N. D., and Hörandl, E. (2018). RAD-seq reveals genetic structure of the F2-generation of natural willow hybrids (Salix L.) and a great potential for interspecific introgression. BMC Plant Biol. 18, 317.

Gray, M. W. (1992). The endosymbiont hypothesis revisited. Int. Rev. Cytol. 141, 233–357. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62068-9

Gray, M. W. (2012). Mitochondrial evolution. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a011403. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011403

Greiner, S., Lehwark, P., and Bock, R. (2019). OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3. 1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W59–W64.

Greiner, S., Sobanski, J., and Bock, R. (2015). Why are most organelle genomes transmitted maternally? Bioessays 37, 80–94. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400110

Gualberto, J. M., Mileshina, D., Wallet, C., Niazi, A. K., Weber-Lotfi, F., and Dietrich, A. (2014). The plant mitochondrial genome: dynamics and maintenance. Biochimie 100, 107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.09.016

Gualberto, J. M. and Newton, K. J. (2017). Plant mitochondrial genomes: dynamics and mechanisms of mutation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 68, 225–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-112232

Gulyaev, S., Cai, X. J., Guo, F. Y., Kikuchi, S., Applequist, W. L., Zhang, Z. X., et al. (2022). The phylogeny of Salix revealed by whole genome re-sequencing suggests different sex-determination systems in major groups of the genus. Ann. Bot. 129, 485–498. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcac012

Guo, W., Grewe, F., Fan, W., Young, G. J., Knoop, V., Palmer, J. D., et al. (2016). Ginkgo and Welwitschia mitogenomes reveal extreme contrasts in gymnosperm mitochondrial evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1448–1460. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw024

Han, F., Qu, Y., Chen, Y., Xu, L., and Bi, C. (2022). Assembly and comparative analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of Salix wilsonii using PacBio HiFi sequencing. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1031769. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1031769

Havey, M. (1997). Predominant paternal transmission of the mitochondrial genome in cucumber. J. Hered. 88, 232–235. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a023094

Havey, M., McCreight, J., Rhodes, B., and Taurick, G. (1998). Differential transmission of the Cucumis organellar genomes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 97, 122–128. doi: 10.1007/s001220050875

He, L., Jia, K. H., Zhang, R. G., Wang, Y., Shi, T. L., Li, Z. C., et al. (2021a). Chromosome-scale assembly of the genome of Salix dunnii reveals a male-heterogametic sex determination system on chromosome 7. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 21, 1966–1982. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13362

He, L., Wagner, N. D., and Hörandl, E. (2021b). Restriction-site associated DNA sequencing data reveal a radiation of willow species (Salix L., Salicaceae) in the Hengduan Mountains and adjacent areas. J. Syst. Evol. 59, 44–57. doi: 10.1111/jse.12593

Hörandl, E., Florineth, F., and Hadacek, F. (2012). Weiden in Österreich und Angrenzenden Gebieten (Willows in Austria and Adjacent Regions). 2nd ed (Vienna: University of Agriculture).

Hu, Y., Zhang, Q., Rao, G., and Sodmergen (2008). Occurrence of plastids in the sperm cells of Caprifoliaceae: biparental plastid inheritance in angiosperms is unilaterally derived from maternal inheritance. Plant Cell Physiol. 49, 958–968. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn069

Huang, C. Y., Grunheit, N., Ahmadinejad, N., Timmis, J. N., and Martin, W. (2005). Mutational decay and age of chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes transferred recently to angiosperm nuclear chromosomes. Plant Physiol. 138, 1723–1733. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060327

Huelsenbeck, J. P. (1995). Performance of phylogenetic methods in simulation. Syst. Biol. 44, 17–48. doi: 10.2307/2413481

Jiang, P., Shi, F. X., Li, M. R., Liu, B., Wen, J., Xiao, H. X., et al. (2018). Positive selection driving cytoplasmic genome evolution of the medicinally important ginseng plant genus Panax. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 359. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00359

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K., and Miyata, T. (2002). MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436

Kearse, M., Moir, R., Wilson, A., Stones-Havas, S., Cheung, M., Sturrock, S., et al. (2012). Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199

Knoop, V., Volkmar, U., Hecht, J., and Grewe, F. (2010). “Mitochondrial genome evolution in the plant lineage,” in Plant mitochondria. Ed. Kempken, F. (Springer, New York), 3–29.

Ku, C., Nelson-Sathi, S., Roettger, M., Sousa, F. L., Lockhart, P. J., Bryant, D., et al. (2015). Endosymbiotic origin and differential loss of eukaryotic genes. Nature 524, 427–432. doi: 10.1038/nature14963

Kuntal, H. and Sharma, V. (2011). In silico analysis of SSRs in mitochondrial genomes of plants. OMICS. 15, 783–789. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0074

Kurtz, S., Choudhuri, J. V., Ohlebusch, E., Schleiermacher, C., Stoye, J., and Giegerich, R. (2001). REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633

Lei, B., Li, S., Liu, G., Wang, Y., Su, A., and Hua, J. (2012). Evolutionary analysis of mitochondrial genomes in higher plants. Mol. Plant Breed. 10, 490–500.

Li, H., Handsaker, B., Wysoker, A., Fennell, T., Ruan, J., Homer, N., et al. (2009). The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352

Li, W., Wu, H., Li, X., Chen, Y., and Yin, T. (2020). Fine mapping of the sex locus in Salix triandra confirms a consistent sex determination mechanism in genus Salix. Hortic. Res. 7, 64. doi: 10.1038/s41438-020-0289-1

Li, Q. Q., Zhang, Z. P., Aogan, and Wen, J. (2024). Comparative chloroplast genomes of Argentina species: genome evolution and phylogenomic implications. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1349358. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1349358

Li, G., Zhang, H., Lin, Z., Hu, G., Xu, G., Xu, Y., et al. (2024). Comparative analysis of chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of sweet potato provides evidence of gene transfer. Sci. Rep. 14, 4547. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-55150-1

Li, Y., Zhou, J., Chen, X., Cui, Y., Xu, Z., Li, Y., et al. (2017). Gene losses and partial deletion of small single-copy regions of the chloroplast genomes of two hemiparasitic Taxillus species. Sci. Rep. 7, 12834. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13401-4

Lynch, M., Koskella, B., and Schaack, S. (2006). Mutation pressure and the evolution of organelle genomic architecture. Science 311, 1727–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.1118884

Mackenzie, S. and McIntosh, L. (1999). Higher plant mitochondria. Plant Cell. 11, 571–585. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.4.571

Manchester, S. R., Judd, W. S., and Handley, B. (2006). Foliage and fruits of early poplars (Salicaceae: Populus) from the Eocene of Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming. Int. J. Plant Sci. 67, 897–908. doi: 10.1086/503918

Marinček, P., Pittet, L., Wagner, N. D., and Hörandl, E. (2023). Evolution of a hybrid zone of two willow species (Salix L.) in the European Alps analyzed by RAD-seq and morphometrics. Ecol. Evol. 13, e9700.

Martin, G., Baurens, F. C., Cardi, C., Aury, J. M., and D’Hont, A. (2013). The complete chloroplast genome of banana (Musa acuminata, Zingiberales): insight into plastid monocotyledon evolution. PLoS One 8, e67350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067350

Martin, M., Casano, L. M., and Sabater, B. (1996). Identification of the product of ndhA gene as a thylakoid protein synthesized in response to photooxidative treatment. Plant Cell Physiol. 37, 293–298. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a028945

Mereschkowsky, C. (1905). Über natur und ursprung der chromatophoren im pflanzenreiche. Biol. Centralbl. 25, 593.

Nguyen, V., Giang, V., Waminal, N., Park, H., Kim, N., Jang, W., et al. (2000). Comprehensive comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes from seven Panax species and development of an authentication system based on species-unique single nucleotide polymorphism markers. J. Ginseng Res. 44, 135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2018.06.003

Ni, Y., Li, J., Chen, H., Yue, J., Chen, P., and Liu, C. (2022). Comparative analysis of the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of Saposhnikovia divaricata revealed the possible transfer of plastome repeat regions into the mitogenome. BMC Genomics 23, 570. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08821-0

Nugent, J. M. and Palmer, J. D. (1991). RNA-mediated transfer of the gene coxII from the mitochondrion to the nucleus during flowering plant evolution. Cell 66, 473–481. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90011-8

Nybakken, L. and Julkunen-Tiitto, R. (2013). Gender differences in Salix myrsinifolia at the pre-reproductive stage are little affected by simulated climatic change. Physiol. Plant 147, 465–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01675.x

Olmstead, R. G. and Palmer, J. D. (1994). Chloroplast DNA systematics: a review of methods and data analysis. Am. J. Bot. 81, 1205–1224. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1994.tb15615.x

Palmer, J. D. (1983). Chloroplast DNA exists in two orientations. Nature 301, 92–93. doi: 10.1038/301092a0

Palmer, J. D. and Herbon, L. A. (1988). Plant mitochondrial DNA evolved rapidly in structure, but slowly in sequence. J. Mol. Evol. 28, 87–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02143500

Passmore, L. A., Schmeing, T. M., Maag, D., Applefield, D. J., Acker, M. G., Algire, M. A., et al. (2007). The eukaryotic translation initiation factors eIF1 and eIF1A induce an open conformation of the 40S ribosome. Mol. Cell. 26, 41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.018

Qiu, Y. L., Li, L., Wang, B., Xue, J. Y., Hendry, T. A., LI, R. Q., et al. (2010). Angiosperm phylogeny inferred from sequences of four mitochondrial genes. J. Syst. Evol. 48, 391–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-6831.2010.00097.x

Qu, X. J., Moore, M. J., Li, D. Z., and Yi, T. S. (2019). PGA: a software package for rapid, accurate, and flexible batch annotation of plastomes. Plant Methods 15, 50. doi: 10.1186/s13007-019-0435-7

Rambaut, A. (2014). FigTree 1.4. 2 software. Available online at: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/fgtree/ (Accessed March 4, 2024).

Rambaut, A., Drummond, A. J., Xie, D., Baele, G., and Suchard, M. A. (2018). Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 67, 901–904. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syy032

Ren, W., Jiang, Z., Zhang, M., Kong, L., Zhang, H., Liu, Y., et al. (2022). The chloroplast genome of Salix floderusii and characterization of chloroplast regulatory elements. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 987443. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.987443

Richardson, A. O., Rice, D. W., Young, G. J., Alverson, A. J., and Palmer, J. D. (2013). The "fossilized" mitochondrial genome of Liriodendron tulipifera: ancestral gene content and order, ancestral editing sites, and extraordinarily low mutation rate. BMC Biol. 11, 29. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-29

Rott, M., Martins, N. F., Thiele, W., Lein, W., Bock, R., Kramer, D. M., et al. (2011). ATP synthase repression in tobacco restricts photosynthetic electron transport, CO2 assimilation, and plant growth by overacidification of the thylakoid lumen. Plant Cell. 23, 304–321.

Sakamoto, W. and Takami, T. (2024). Plastid inheritance revisited: emerging role of organelle DNA degradation in angiosperms. Plant Cell Physiol. 65, 484–492. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcad104

Sanderson, B. J., Gambhir, D., Feng, G., Hu, N., Cronk, Q. C., Percy, D. M., et al. (2023). Phylogenomics reveals patterns of ancient hybridization and differential diversification that contribute to phylogenetic conflict in willows, poplars, and close relatives. Syst. Biol. 72, 1220–1232. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syad042

Santos, T. R. S., Torre, F. D., Santos, J. A. S., Pereira, E. G., and Garcia, Q. S. (2025). Growth-tolerance tradeoffs shape the survival outcomes and ecophysiological strategies of Atlantic Forest species in the rehabilitation of mining-impacted sites. Sci. Total Environ. 964, 178567. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.178567

Shen, J., Lyu, X., Xu, X., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Wang, C., et al. (2025). A nuclear-encoded endonuclease governs the paternal transmission of mitochondria in Cucumis plants. Nat. Commun. 16, 4266. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-59568-7

Sinn, B. T., Sedmak, D. D., Kelly, L. M., and Freudenstein, J. V. (2018). Total duplication of the small single copy region in the angiosperm plastome: rearrangement and inverted repeat instability in Asarum. Am. J. Bot. 105, 71–84. doi: 10.1002/ajb2.1001

Skvortsov, A. K. (1999). Willows of Russia and adjacent countries. Taxonomical and geographical revision. Univ. Joensuu Faculty Mathematics Natural Sciences Rep. Ser. Biol. 39, 1–307.

Smith, D. R. (2014). Mitochondrion-to-plastid DNA transfer: it happens. New Phytol. 202, 736–738. doi: 10.1111/nph.12704

Smith, D. R. and Keeling, P. J. (2015). Mitochondrial and plastid genome architecture: Reoccurring themes, but significant differences at the extremes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 10177–10184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422049112

Som, A. (2014). Causes, consequences and solutions of phylogenetic incongruence. Brief. Bioinform. 16, 536–548. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbu015

Song, Y., Feng, L., Alyafei, M. A. M., Jaleel, A., and Ren, M. (2021). Function of chloroplasts in plant stress responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 13464. doi: 10.3390/ijms222413464

Steane, D. A. (2005). Complete nucleotide sequence of the chloroplast genome from the Tasmanian blue gum, Eucalyptus globulus (Myrtaceae). DNA Res. 12, 215–220. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi006

Straub, S. C., Cronn, R. C., Edwards, C., Fishbein, M., and Liston, A. (2013). Horizontal transfer of DNA from the mitochondrial to the plastid genome and its subsequent evolution in milkweeds (Apocynaceae). Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 1872–1885. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt140

Sullivan, J. and Joyce, P. (2005). Model selection in phylogenetics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 36, 445–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102003.152633

Sun, M., Zhang, M., Chen, X., Liu, Y., Liu, B., Li, J., et al. (2022). Rearrangement and domestication as drivers of Rosaceae mitogenome plasticity. BMC Biol. 20, 181. doi: 10.1186/s12915-022-01383-3

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., and Kumar, S. (2021). MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120

Tillich, M., Lehwark, P., Pellizzer, T., Ulbricht-Jones, E. S., Fischer, A., Bock, R., et al. (2017). GeSeq–versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W6–W11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx391

Timmis, J. N., Ayliffe, M. A., Huang, C. Y., and Martin, W. (2004). Endosymbiotic gene transfer: organelle genomes forge eukaryotic chromosomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 123–135. doi: 10.1038/nrg1271

Trybush, S., Jahodová, Š., Macalpine, W., and Karp, A. (2008). A genetic study of a Salix germplasm resource reveals new insights into relationships among subgenera, sections and species. Bioenergy Res. 1, 67–79. doi: 10.1007/s12155-008-9007-9

Tyszka, A. S., Bretz, E. C., Robertson, H. M., Woodcock-Girard, M. D., Ramanauskas, K., Larson, D. A., et al. (2023). Characterizing conflict and congruence of molecular evolution across organellar genome sequences for phylogenetics in land plants. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1125107. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1125107

Varré, J. S., D’Agostino, N., Touzet, P., Gallina, S., Tamburino, R., Cantarella, C., et al. (2019). Complete sequence, multichromosomal architecture and transcriptome analysis of the Solanum tuberosum mitochondrial genome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4788. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194788

Vašut, R. J., Pospíšková, M., Lukavský, J., and Weger, J. (2024). Detection of hybrids in willows (Salix, Salicaceae) using genome-wide DArTseq markers. Plants (Basel). 13, 639. doi: 10.3390/plants13050639

Wagner, N. D., Gramlich, S., and Hörandl, E. (2018). RAD sequencing resolved phylogenetic relationships in European shrub willows (Salix L. subg. Chamaetia and subg. Vetrix) and revealed multiple evolution of dwarf shrubs. Ecol. Evol. 8, 8243–8255. doi: 10.1002/ece3.4360

Wagner, N. D., He, L., and Hörandl, E. (2020). Phylogenomic relationships and evolution of polyploid Salix species revealed by RAD sequencing data. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 1–38. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01077

Wagner, N. D., He, L., and Hörandl, E. (2021a). The evolutionary history, diversity, and ecology of willows (Salix l.) in the European alps. Diversity 13, 146. doi: 10.3390/d13040146

Wagner, N. D., Volf, M., and Hörandl, E. (2021b). Highly diverse shrub willows (Salix L.) share highly similar plastomes. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 662715. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.662715

Wang, Y. and Yang, H. (2016). The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Salix babylonica. Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp. Seq. Anal. 27, 4683–4684.

Wee, C. C., Nor Muhammad, N. A., Subbiah, V. K., Arita, M., Nakamura, Y., and Goh, H. H. (2022). Mitochondrial genome of Garcinia mangostana L. variety Mesta. Sci. Rep. 12, 9480. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13706-z

Westhoff, P., Alt, J., Nelson, N., and Herrmann, R. G. (1985). Genes and transcripts for the ATP synthase CF 0 subunits I and II from spinach thylakoid membranes. Mol. Gen. Genet. MGG. 199, 290–299. doi: 10.1007/BF00330271

Wicke, S., Schneeweiss, G. M., Depamphilis, C. W., Müller, K. F., and Quandt, D. (2011). The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol. Biol. 76, 273–297. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4

Wu, J. and Li, X. (2022). Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Salix koreensis Anderss (Salicaceae) 1868. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 7, 1131–1133. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2022.2087561

Wu, J., Nyman, T., Wang, D. C., Argus, G. W., Yang, Y. P., and Chen, J. H. (2015). Phylogeny of Salix subgenus Salix s.l. (Salicaceae): delimitation, biogeography, and reticulate evolution. BMC Evol. Biol. 15, 31.

Yamori, W., Sakata, N., Suzuki, Y., Shikanai, T., and Makino, A. (2011). Cyclic electron flow around photosystem I via chloroplast NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (NDH) complex performs a significant physiological role during photosynthesis and plant growth at low temperature in rice. Plant J. 68, 966–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04747.x

Yang, Z. (2007). PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088

Yang, T., Zhang, Q., Yang, C., and Qiu, J. (2022). The complete chloroplast genome of Salix matSudana f. tortuosa. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 7, 1794–1796. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2022.2110007

Ye, N., Wang, X., Li, J., Bi, C., Xu, Y., Wu, D., et al. (2017). Assembly and comparative analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequence of an economic plant Salix suchowensis. PeerJ 5, e3148. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3148

Yuan, Z., Wu, D., Wen, Y., Xu, W., Gao, W., Dahn, H. A., et al. (2023). Historical mitochondrial genome introgression confounds species delimitation: evidence from phylogenetic inference in the Odorrana grahami species complex. Curr. Zool. 69, 82–90. doi: 10.1093/cz/zoac010

Yuan, F., Zhou, L., Wei, X., Shang, C., and Zhang, Z. (2025). Comparative chloroplast genomics reveals intrageneric divergence in Salix. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 2248. doi: 10.3390/ijms26052248

Yue, Y., Li, J., Sun, X., Li, Z., and Jiang, B. (2023). Polymorphism analysis of the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 23, 15. doi: 10.1186/s12870-022-04028-3

Yue, J., Lu, Q., Ni, Y., Chen, P., and Liu, C. (2022). Comparative analysis of the plastid and mitochondrial genomes of Artemisia giraldii Pamp. Sci. Rep. 12, 13931. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-18387-2